Challenges Facing Andean Communities in the Protection of the Páramo in the Central Highlands of Ecuador

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Framework

2.1. Technology and Society

2.2. Socio-Technical Approach

3. Materials and Methods

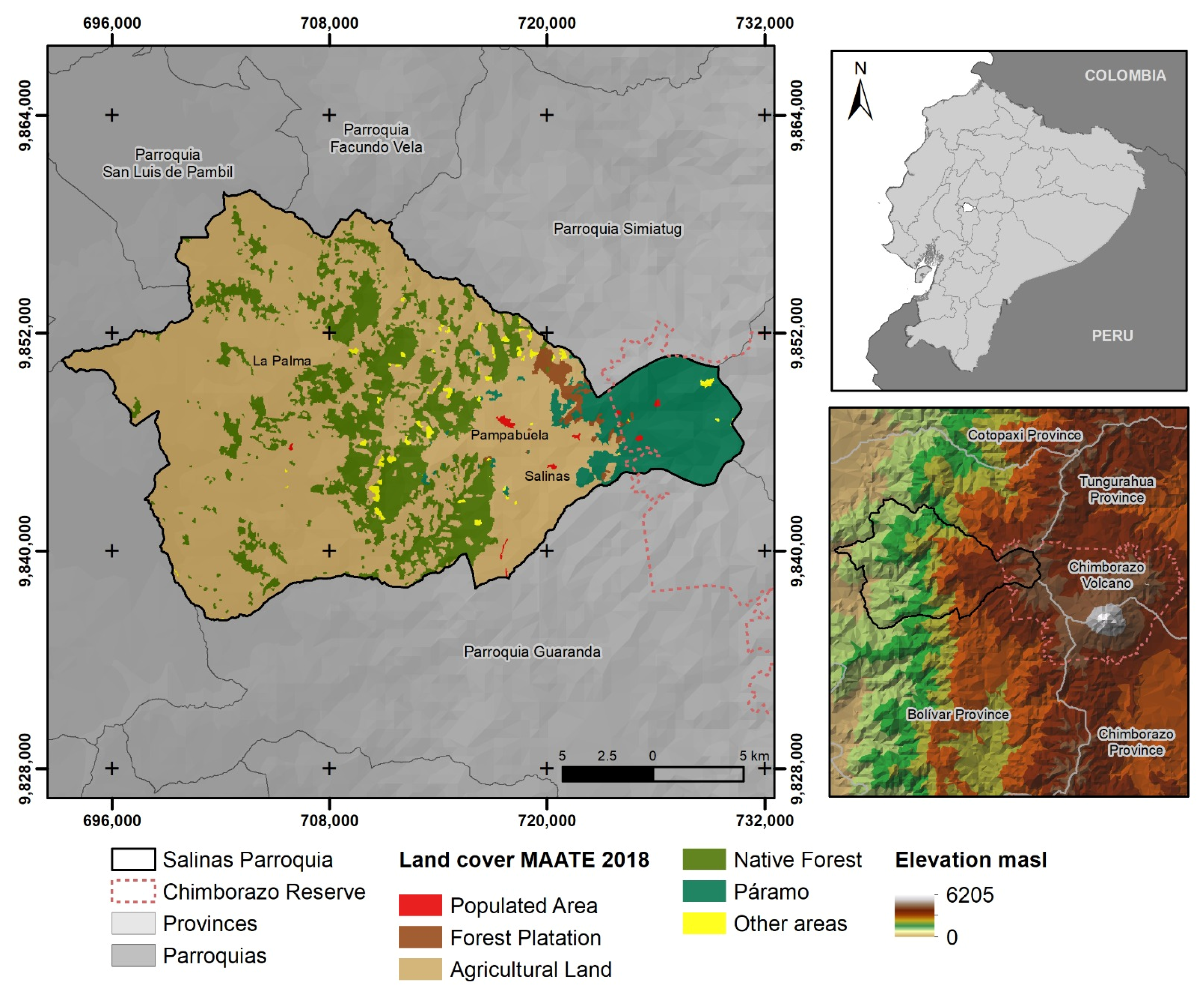

3.1. Study Area

3.2. Methodology

4. Results

4.1. Historical Review

- Construction of basic infrastructure (1970–1978): The projects focused on providing water, electricity, access roads, more appropriate housing for human life, a communal house for assemblies, a co-community school and a place for the meetings of a reborn community [54]. The Salinas Savings and Credit Cooperative (COACSAL) was created. It was a transcendental organization for the development of productive projects. It was also the promoter of other second-order organizations such as the Salinas Community Organizations Foundation (FUNORSAL), Salinas Textiles (TEXSAL) and Salinas Youth Group Foundation (FUGJS), among others. The key to the economic development of the area was through their technical assistance [41,54,56]. The Fondo Ecuatoriano Populorum Progressio (FEPP) provided peasants with loans that allowed them to buy land and dairy cattle from the haciendas in the area. It also promoted the introduction of cheese factories [54]; this stimulated the purchase of livestock and the adaptation of páramo land to pasture.

- Development of production and marketing systems (1978–1990): The name “Salinerito” began to be used as a brand name for cheeses from this area with a message of economic solidarity [54]. A research program on rural dairy products in Ecuador was initiated. A store was opened in Quito (the capital), thus launching a large market [57]. This led to the creation of about thirty local cheese factories, which accounted for 90% of family incomes [54]. The communities began to grow and settle in increasingly higher areas without considering the extreme climatic conditions that made agriculture and cattle raising complex [58]. Nature was transforming, and the advance of the agricultural frontier gradually deteriorated the páramo without causing significant damage during this period [59]. The families raised hundreds of sheep throughout the communal area and provided wool and meat [13]. The Salinas Salesian Family Foundation (SSFF) promoted other economic initiatives related to jam, sausages, nougat, soy products, chocolates, herbal teas, wool sacks, compost, essential pine oils and mushrooms, among others [54]. The landscape began to take a significant turn, marking the initiation of future interest in environmental protection [54].

- Decentralization of the production system (1990–present): The organization was no longer sufficient. The challenge was to create, diversify and consolidate sources of employment that allowed people to escape poverty with new criteria [54]. Under the concept of trial and error, new products were developed [41]. The government opened several job positions. Tourism began to make headway regarding community enterprises spontaneously and without planning, with fragmented food and lodging services [57]. The Salinas Group began coordinating, articulating and facilitating project access and supporting local initiatives to strengthen the community work process [54].

Relevant Environmental Background and Challenges to Overcome

4.2. Field Observation

- Accentuated advancement of the agricultural frontier, with a fragmented páramo and many patches of pine forest (Figure 2a). This situation is observed even within the NSPA in the Chimborazo Faunistic Reserve.

- There are some communities that are not participating in the conservation and solidarity efforts started in Salinas for the conservation of the páramo (Figure 2b).

- The women are organized and are interested in promoting new ventures, such as handicrafts made from páramo straw (Figure 2c).

- Use of heavy machinery to prepare the soil for pasture significantly impacts soil structure (Figure 2a).

- The communities have a significant social organization, as evidenced by communal assemblies and Monday reflections facilitated by the FFSS (Figure 2d).

- Cheese shops are a vital part of the communities, with sheep cheese gaining popularity.

- Very well-defined páramo reserve areas, free from agriculture and livestock, with improved soil conditions and increased native páramo vegetation. Visitors are only allowed entry as tourists (Figure 2f).

- The Salineran companies are well organized and in good working order.

- Eroded areas are being restored through reforestation with native plants and shrubs.

- The communities are engaging in other activities that do not involve livestock or agriculture (weaving, mushroom harvesting, llama sausages, mortiño jam and trout farms, among others).

- Social and environmental organizations are active, and national and international volunteers are present.

4.3. Interviews

4.3.1. Measures to Protect the Páramo and Its Constraints

4.3.2. Socio-Technical Reconfiguration for Conservation

5. Discussion

5.1. Resources

5.2. Mindset

5.3. Authority

5.4. Organization

5.5. Technical Support and Training

5.6. Sustainability

5.7. Gender Equity

5.8. Creativity

5.9. Reflection

5.10. Local Knowledge

5.11. Nature

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hofstede, R.; Calles, J.; López, V.; Polanco, R.; Torres, F.; Ulloa, J.; Vásquez, A.; Cerra, M. Los Páramos Andinos ¿Qué Sabemos? Estado de Conocimiento Sobre el Impacto del Cambio Climático en el Ecosistema Páramo; UICN: Quito, Ecuador, 2014; p. 154. [Google Scholar]

- Cresso, M.; Clerici, N.; Sanchez, A.; Jaramillo, F. Future climate change renders unsuitable conditions for paramo ecosystems in Colombia. Sustainability 2020, 12, 8373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buytaert, W.; Célleri, R.; De Bièvre, B.; Cisneros, F.; Wyseure, G.; Deckers, J.; Hofstede, R. Human impact on the hydrology of the Andean paramos. Earth Sci. Rev. 2006, 79, 53–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Llambí, L.; Soto, A.; Célleri, R.; De Bièvre, B.; Ochoa-Tocachi, B.; Borja, P. Ecología, Hidrología y Suelos de Páramos; CONDESAN: Quito, Ecuador, 2012; p. 280. [Google Scholar]

- Suárez, E.; Chimbolema, S.; Jaramillo, R.; Zurita, L.; Arellano, P.; Chimner, R.; Stanovick, J.; Lilleskov, E. Challenges and opportunities for restoration of high-elevation Andean peatlands in Ecuador. Mitig. Adapt. Strateg. Glob. Change 2022, 27, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beltrán, K.; Salgado, S.; Cuesta, F.; León-Yánez, S.; Romoleroux, K.; Ortiz, E.; Cárdenas, A.; Velástegui, A. Distribución Espacial, Sistemas Ecológicos y Caracterización Florística de los Páramos en el Ecuador; EcoCiencia, Proyecto Páramo Andino y Herbario QCA: Quito, Ecuador, 2009; p. 152. [Google Scholar]

- Rey, D.; Domínguez, I.; Oviedo, E. Effect of agricultural activities on surface water quality from páramo ecosystems. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2022, 29, 83169–83190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofstede, R.; Groenendijk, J.; Coppus, R.; Fehse, J.; Sevink, J. Impact of Pine Plantations on Soils and Vegetation in the Ecuadorian High Andes. Mt. Res. Dev. 2002, 22, 159–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Avellaneda-Torres, L.; Torres, E.; León, T. Alternativas ante el conflicto entre autoridades ambientales y habitantes de áreas protegidas en páramos colombianos. Mundo Agrar. 2015, 16, 1–26. Available online: http://www.mundoagrario.unlp.edu.ar/article/view/MAv16n31a10 (accessed on 14 February 2023).

- Leroy, D.; Barrasa, S. Which Ecosystem Services Are Really Integrated into Local Culture? Farmers’ Perceptions of the Colombian and Venezuelan Páramos. Hum. Ecol. 2021, 49, 385–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mena, P.; Castillo, A.; Flores, S.; Hofstede, R.; Josse, C.; Lasso, S.; Medina, G.; Ochoa, N.; Ortiz, D. (Eds.) Páramo: Paisaje Estudiado, Habitado, Manejado e Institucionalizado; EcoCiencia/Abya-Yala/ECOBONA: Quito, Ecuador, 2011; p. 376. [Google Scholar]

- Chuncho, C.; Chuncho, G. Páramos del Ecuador, importancia y afectaciones: Una revisión. Bosques Latid. Cero 2019, 9, 72–76. [Google Scholar]

- Calvo, J.; Villaverde, X. (Eds.) Alianzas Para el Desarrollo Local; PAB: Quito, Ecuador, 2011; p. 372. [Google Scholar]

- Pomboza, P.; Parco, A. Efectos socio-ambientales de la intensificación de la ganadería en ecosistemas de altura (páramos) del sur-oeste de Tungurahua. Ecosistemas 2022, 31, 2296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mena, P.; Hofstede, R. Los páramos ecuatorianos. In Botánica Económica de los Andes Centrales; Moraes, M., Øllgaard, B., Kvist, L., Borchsenius, F., Balslev, H., Eds.; Universidad Mayor de San Andrés: La Paz, Bolivia, 2006; pp. 91–109. [Google Scholar]

- Riggs, R.; Langston, J.; Sayer, J.; Sloan, S.; Laurance, W. Learning from Local Perceptions for Strategic Road Development in Cambodia’s Protected Forests. Trop. Conserv. Sci. 2020, 13, 1940082920903183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Vergara, P.; Ortiz, L. Reconocimiento de los saberes locales como aporte a la conservación del territorio campesino, páramo de Rabanal, Boyacá, Colombia. Rev. Geogr. Venez. 2021, 62, 480–489. [Google Scholar]

- Ramón, G. Visiones, Usos e Intervenciones en los Páramos del Ecuador; GTP/Abya-Yala: Quito, Ecuador, 2002; pp. 43–50. [Google Scholar]

- Torres, M.; Naranjo, E.; Fierro, V. Social Technology for the Protection of the Páramo in the central zone of Ecuador. Mt. Res. Dev. 2022, submitted.

- Ortega y Gasset, J. Meditación de la Técnica; Biblioteca Nueva: Madrid, Spain, 2015; p. 162. [Google Scholar]

- Winner, L. La Ballena y el Reactor, 2nd ed.; Gedisa: Barcelona, Spain, 2013; p. 187. [Google Scholar]

- Aguiar, D. Determinismo Tecnológico versus Determinismo Social: Aportes Metodológicos y Teóricos de la Filosofía, la Historia, la Economía y la Sociología de la Tecnología; Universidad Nacional de La Plata: Buenos Aires, Argentina, 2002; p. 92. [Google Scholar]

- Broncano, F. Mundos Artificiales; PAIDOS: Barcelona, Spain, 2001; p. 328. [Google Scholar]

- Thomas, H. Tecnologías para la inclusión social en América Latina: De las tecnologías apropiadas a los sistemas tecnológicos sociales. Problemas conceptuales y soluciones estratégicas. In Tecnología, Desarrollo y Democracia. Nueve Estudios Sobre Dinámicas Sociotécnicas de Exclusión/Inclusión Social; Thomas, H., Fressoli, M., Santos, G., Eds.; CROLAR: Buenos Aires, Argentina, 2012; Volume 3, pp. 25–78. [Google Scholar]

- Pinch, T. The social construction of technology: Where it came from and where it might be heading. In Social Constructivism as Paradigm? 1st ed.; Pfadenhauer, M., Knoblauch, H., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2018; pp. 152–164. [Google Scholar]

- Valderrama, A. Teoría y crítica de la construcción social de la tecnología. Rev. Colomb. Sociol. 2004, 23, 217–233. [Google Scholar]

- Fernández, A. El Constructivismo Social en la Ciencia y la Tecnología: Las Consecuencias no previstas de la Ambivalencia Epistemológica. ARBOR Cienc. Pensam. Cult. 2009, 738, 689–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tabares, J.; Correa, S. Tecnología y sociedad: Una aproximación a los estudios sociales de la tecnología. Rev. Iberoam. Cienc. Tecnol. Soc. 2014, 9, 129–144. [Google Scholar]

- Gómez, R. Tecnología y Sociedad. Una Filosofía Política, 1st ed.; CICCUS: Buenos Aires, Argentina, 2021; p. 202. [Google Scholar]

- Czarniawska, B. Bruno Latour and Niklas Luhmann as organization theorists. Eur. Manag. J. 2017, 35, 145–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farías, D. Reseña. Aramis or the love of technology. Int. J. Eng. Soc. Justice Peace 2021, 8, 170–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aibar, E.; Quintanilla, M. Cultura Tecnológica: Estudios de Ciencia, Tecnología y Sociedad, 1st ed.; Horsori: Barcelona, Spain, 2002; p. 254. [Google Scholar]

- Hughes, T. The Seamless Web: Technology, Science, Etcetera, Etcetera. Soc. Stud. Sci. 1986, 16, 281–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lepratte, L. Sociotechnical systems, innovation and development. Munich Pers. RePEc Arch. 2011, 33559. Available online: https://mpra.ub.uni-muenchen.de/33559/ (accessed on 13 March 2023).

- Nuñez, J.; García, R. Universidad, ciencia, tecnología y desarrollo sostenible. Espacios 2017, 38, 3–15. Available online: https://www.revistaespacios.com/a17v38n39/17383903.html (accessed on 24 March 2023).

- Pozzebon, M.; Fontenelle, I. Fostering the post-development debate: The Latin American concept of tecnologia social. Third World Q. 2018, 39, 1750–1769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, H.; Becerra, L.; Bidinost, A. ¿Cómo funcionan las tecnologías? Alianzas socio-técnicas y procesos de construcción de funcionamiento en el análisis histórico. Pasado Abierto 2019, 10, 127–158. Available online: http://fh.mdp.edu.ar/revistas/index.php/pasadoabierto (accessed on 21 March 2022).

- Vercelli, A. Reconociendo las tecnologías sociales como bienes comunes. Rev. Íconos 2010, 37, 55–64. Available online: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=50918216004 (accessed on 15 August 2022).

- Torres, M.; Naranjo, E. Tecnología Social en el Ecuador. Rev. Ven. Geren. 2022, 27, 1215–1230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montalván, J.; Guerrero, W.; Maruri, J. Estudio de identificación de factores de éxito de gestión de los asociados comunitarios de Salinas de Guaranda. Univ. Soc. 2020, 12, 290–295. Available online: http://scielo.sld.cu/pdf/rus/v12n3/2218-3620-rus-12-03-290.pdf (accessed on 16 February 2023).

- Naranjo, E.; Abad, A.; Ramos, V. Factores Culturales de Logro del Sistema de Producción Comunitaria de la Parroquia Salinas en la Provincia de Bolívar, Ecuador. Chakiñan 2018, 6, 136–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Instituto Geográfico Militar. Catálogo de Objetos del IGM Versión 4.0. Available online: https://www.geoportaligm.gob.ec/portal/index.php/cartografia-de-libre-acceso-escala-50k/ (accessed on 26 April 2023).

- Ricoy, C. Contribución sobre los paradigmas de investigación. Educação Rev. Cent. Educ. UFSM 2006, 31, 11–22. Available online: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=117117257002 (accessed on 24 April 2022).

- Reyes, L.; Carmona, F. La Investigación Documental Para la Comprensión Ontológica del Objeto de Estudio; Universidad Simón Bolívar: Barranquilla, Colombia, 2020; p. 55. [Google Scholar]

- Kawulich, B. La observación participante como método de recolección de datos. Forum Qual. Soc. Res. 2005, 6, 1–32. Available online: http://biblioteca.udgvirtual.udg.mx/jspui/handle/123456789/2715 (accessed on 18 May 2022).

- Hernández, R.; Mendoza, C. Metodología de la Investigación. Las Rutas Cuantitativa, Cualitativa y Mixta; McGraw Hill: Mexico City, Mexico, 2018; p. 753. [Google Scholar]

- Algranati, S.; Bruno, D.; Iotti, A. Mapear Actores, Relaciones y Territorios. Una herramienta para el análisis del escenario social. In Taller de Planificación de Procesos Comunicacionales Facultad de Periodismo y Comunicación Social; Universidad Nacional de La Plata: Buenos Aires, Argentina, 2012; Volume 3, pp. 2–22. [Google Scholar]

- Tarrés, M. (Ed.) Observar, Escuchar y Comprender Sobre la Tradición Cualitativa en la Investigación Social; El Colegio de México/FLACSO: Mexico City, Mexico, 2014; p. 95. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, S.; Bogdan, R.; DeVault, M. Introduction to Qualitative Research Methods: A Guidebook and Resource; John Wiley & Sons: Barcelona, Spain, 2015; pp. 31–49. [Google Scholar]

- Van-Dijk, T. Análisis Crítico del Discurso. Rev. Austral. Cienc. Soc. 2016, 30, 203–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayala Mora, E. Resumen de Historia del Ecuador, 3rd ed.; Corporación Editora Nacional: Quito, Ecuador, 2008; p. 58. [Google Scholar]

- Mata, O. Los Proyectos Solidarios de Salinas de Guaranda y su Aporte Para la Construcción de “Otra Economía”. Master’s Thesis, Facultad Latinoamericana de Ciencias Sociales (FLACSO), Quito, Ecuador, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Naranjo, E. Cultura Local y Gestión. Ph.D. Thesis, Universidad Andina Simón Bolívar, Quito, Ecuador, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Polo, A. La Laguna de los Sueños. Entre los Recuerdos del Pasado y las Visiones del Futuro de un Misionero Salesiano en los Andes Ecuatorianos; Abya Yala: Quito, Ecuador, 2021; p. 268. [Google Scholar]

- Anchundia, M.; García, K.; Cedeño, W. Los aportes de las mujeres rurales a la Economía Solidaria en Salinas de Guaranda: El caso de las tejedoras de Texsal. In XIV Jornadas Nacionales y VI Internacionales de Investigación y Debate sobre el Mundo Rural Latinoamericano de los Siglos XX y XXI; Universidad Nacional de Quilmes: Buenos Aires, Argentina, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Almendariz, V.; Castillo, S.; Cuestas, J. Análisis de las Herramientas de Gestión que utilizan las Unidades Productivas Comunitarias en la Parroquia Salinas de la Provincia de Bolívar. Rev. Polit. 2013, 32, 118–126. Available online: https://revistapolitecnica.epn.edu.ec/ojs2/index.php/revista_politecnica2/article/view/7 (accessed on 25 January 2023).

- Lupera, M.; Zambrano, I. La puerta abierta “30 años de aventura misionera y social en Salinas de Bolívar Ecuador”: Análisis y Revisión. Reciamuc 2018, 2, 151–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camacho, M. Los páramos ecuatorianos: Caracterización y consideraciones para su conservación y aprovechamiento sostenible. Rev. An. 2014, 1, 77–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calvo, J. (Ed.) Alianzas Para el Circuito Económico Social y Solidario. Metodología y Estrategia de Desarrollo en el Territorio; FEEP/MCCH/IEDECA/CAMARI/OBRA SOCIAL “LA CAIXA”/MEDISCUSMUNDI: Quito, Ecuador, 2015; p. 170. [Google Scholar]

- Alvarado, J. Minería y Conflictos de Contenido Ambiental en Ecuador. Ph.D. Thesis, Facultad Latinoamericana de Ciencias Sociales (FLACSO), Quito, Ecuador, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Borja, C. El Ejercicio del Derecho a la Resistencia a los Proyectos Mineros en la Provincia Bolívar. Aportes Para una Discusión Plural de Sus Formas. El Caso del Proyecto Minero Curipamba Sur. Master’s Thesis, Universidad Andina Simón Bolívar, Quito, Ecuador, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Hofstede, R.; Vásconez, S.; Cerra, M. (Eds.) Vivir en los Páramos: Percepciones, Vulnerabilidades, Capacidades y Gobernanza ante el Cambio Climático; UICN: Quito, Ecuador, 2015; p. 278. [Google Scholar]

- Tuaza, L.; Jonhson, C.; Mcburney, M. Comunidad indígena de San Rafael de Chuquipogio, Chimborazo: Transformaciones agrarias y cambio climático. REHPA 2020, 3, 57–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez, A. La normativa como alternativa para garantizar el derecho humano al agua frente al cambio climático: Regulación de las áreas de protección hídrica en el Ecuador. Rev. Derecho Ambient. 2019, 12, 135–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quiroz, C.; Crespo, P.; Stimm, B.; Murtinho, F.; Weber, M.; Hildebrandt, P. Contrasting Stakeholders’ Perceptions of Pine Plantations in the Páramo Ecosystem of Ecuador. Sustainability 2018, 10, 1707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Avellaneda, L.; Torres, E.; León, T. Agricultura y vida en el páramo: Una mirada desde la vereda El Bosque (Parque Nacional Natural de Los Nevados). Cuad. Desarro. Rural 2014, 11, 105–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Jarabo, P. Aspectos generales sobre servicios ecosistémicos e instrumentos como el pago de servicios hidrológicos y fondos de agua para asegurar la calidad y seguridad hídrica. Rev. Investig. Cien. Juríd. Soc. Polít. Momba’etéva 2021, 2, 68–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zolla, C.; Márquez, E. Los Pueblos Indígenas de México: 100 Preguntas; UNAM: Mexico City, Mexico, 2004; p. 377. [Google Scholar]

- Borja, C. El derecho a la resistencia a los proyectos mineros. El caso del proyecto Curipamba Sur, en la provincia de Bolívar, Ecuador. Crít. Resist. Rev. Confl. Soc. Latinoam. 2022, 14, 224–243. Available online: http://id.caicyt.gov.ar/ark:/s25250841/4c42tkzem (accessed on 17 January 2023).

- Lasso, R. Zonas de Altura y Páramos: Espacios de Vida y Desarrollo; AVSF-CAMAREN-ECOCIENCIA: Quito, Ecuador, 2009; p. 130. [Google Scholar]

- Coral, C.; Chávez, M.; Fernández, C.; Pérez, C. Economía social: Sumak Kawsay y empoderamiento de la mujer. Espacios 2018, 39, 34–48. Available online: https://www.revistaespacios.com/a18v39n32/a18v39n32p34.pdf (accessed on 26 February 2023).

- Aldás, J. Critica de la Participación de la Mujer en el Proceso Comunitario de la Parroquia Salinas de la Provincia Bolívar, Caso Texsal. Bachelor’s Thesis, Escuela Politécnica Nacional, Quito, Ecuador, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Scholtus, S.; Domato, O. El rol protagónico de la mujer en el desarrollo sustentable de la comunidad. Apunt. Univ. 2015, 5, 9–34. Available online: https://revistas.upeu.edu.pe/index.php/ra_universitarios/article/view/67 (accessed on 15 March 2023). [CrossRef]

- Eizenberg, E.; Jabareen, Y. Social sustainability: A new conceptual framework. Sustainability 2017, 9, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cantero, P. Salinas de Guaranda: Horizonte de Economía Solidaria; Abya Yala: Quito, Ecuador, 2012; p. 142. [Google Scholar]

- Araya, L.; Ganga, F.; Letzkus, M.; Álvarez, D. Análisis del Discurso de Docentes Universitarios sobre Prácticas Educativas. Front. J. Soc. Technol. Environ. Sci. 2022, 11, 236–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garrido, A.; Cottyn, H.; Martínez-Medina, S.; Wheatley, C.; Sánchez, A.; Kirshner, J.; Cowie, H.; Touza-Montero, J.; White, P. Oso, osito ¿a qué venís? Andean bear conflict, conservation, and campesinos in the colombian páramos. Sustainability 2021, 13, 10489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guzmán, V.; Alvarado, N.; Alvarado, E. Rasgos culturales de los Chimbus y Guarangas en la provincia de Bolívar. Rev. Cient. UISRAEL 2020, 7, 43–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cruz, M. Cosmovisión Andina e Interculturalidad: Una Mirada al Desarrollo Sostenible desde el Sumak Kawsay. Chakiñan 2018, 5, 119–132. Available online: http://scielo.senescyt.gob.ec/pdf/rchakin/n5/2550-6722-rchakin-05-00119.pdf (accessed on 11 April 2023).

- Buytaert, W.; De Bievre, B.; Deckers, J.; Dercon, G.; Govers, G.; Poesen, J. Impact of land use changes on the hydrological properties of volcanic ash soils in South Ecuador. Soil Use Manag. 2002, 18, 94–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De la Cruz, R.; Mena Vásconez, P.; Morales, M.; Ortiz, P.; Ramón, G.; Rivadeneira, S.; Suárez, E.; Terán, J.; Velázquez, C. Gente y Ambiente de Páramo: Realidades y Perspectivas en el Ecuador; EcoCiencia-AbyaYala: Quito, Ecuador, 2009; p. 127. [Google Scholar]

- Meza, J.; Meza, T.; Terranova, J. El Turismo Fuente de Desarrollo: Caso de Estudio: Parroquia Salinas de Guaranda. In Proceedings of the XII Congreso Virtual Internacional Turismo y Desarrollo, Malaga, Spain, 12 July 2018. [Google Scholar]

| Climate Zone | Altitude (masl) | Temperature (°C) | Communities |

|---|---|---|---|

| Páramo | 3000–4000 | 6–12 | Salinas, Apahua, Las Mercedes de Pumín, Pambabuela, San Vicente, Verdepamba, Natahua, Yurauksha, Pachancho, Piscotero, La Moya, Yacubiana |

| Inter-Andean | 2000–3000 | 12–18 | La Palma, Los Arrayanes, Chaupi, Tres Marías, Tigre Urco |

| Subtropical | 600–2000 | 18–24 | Bellavista, El Calvario, Cañitas, Chazojuan, Copalpamba, Gramalote, Guarumal, La Libertad, Lanzahurco, Matiaví Bajo, Monoloma, Muldiaguan, Río Verde |

| No. Interviewed | Characterization |

|---|---|

| E1 | Salinas resident/communicator |

| E2 | Cantonal DAG authority/environmental activist |

| E3 | Parish DAG authority/community leader |

| E4 | NGO social project technician |

| E5 | Community leader |

| E6 | NGO forestry expert |

| E7 | NGO executive director |

| E8 | Inhabitant of Salinas/Straw handicraft expert |

| E9 | DAG parish authority |

| E10 | NGO agricultural expert/páramo specialist |

| E11 | NGO agricultural expert/environmentalist |

| E12 | DAG parish authority |

| E13 | NGO agricultural expert/páramo specialist |

| E14 | Community leader |

| E15 | Salinas resident/youth environmental activist |

| E16 | NGO social projects expert |

| E17 | Community leader |

| E18 | Community leader/weaver |

| E19 | Expert on agricultural issues NGO |

| E20 | Community leader |

| E21 | Salinas resident/merchant |

| E22 | Cantonal DAG authority/environmental area |

| E23 | DAG parish authority |

| E24 | Salinas Water Board Representative |

| E25 | Salinas financial institution director |

| E26 | Salinas resident/teacher |

| Questionnaire 1 |

|---|

|

| Questionnaire 2 |

|

| Actions | Description | Limitation (Perception) |

|---|---|---|

| Conservation | Delimitation of páramo areas in the highest parts, declaring them water reserve zones, prohibiting access by livestock, hunters and human settlements. | “Reaching agreements between families and authorities has been the biggest social problem, as well as reaching agreements with everyone” (E22). “Not everyone is in agreement because people expect immediate results, and it takes 10 to 15 years to see the effects of conservation” (E21). |

| Restoration | Reforestation of degraded areas resulting from burning or erosion with native páramo species. | “We work with pine trees in areas below the reserve to cultivate mushrooms and firewood. We looked for specific areas for planting, trying not to impact the soils, without further advice and through trial and error” (E9). “There are many families that are dedicated to the cultivation of pine trees as a means of subsistence, which is why they are opposed to replacing them with native species” (E10). |

| Change in livestock ownership dynamics | Reduction in sheep and cattle, mainly by limiting grazing areas and acquiring genetically improved sheep (triple purpose), which consume less water and grass. | “Having people leave their physical space where they have been raised since childhood, the land is the mother (…) getting rid of their animals, going from 100, 200 to 10, was a difficult aspect that people did not understand” (E2). |

| Creation of socioeconomic alternatives | Complementary activities to agriculture and cattle ranching take pressure off the use of the páramo (tourism, handicrafts and medicinal plants, among others). | “It is not easy to balance the issue of páramo management; it is necessary to create markets that accept the proposed products, such as llama meat, for example” (E7). |

| Construct | Description | Segment Example |

|---|---|---|

| Resources | Financial support from many public and private entities for the execution of projects. | “The motivation to improve the living conditions of the inhabitants of this area was such that countless contributors from all over the world, of all religious beliefs and all political orientations, joined together to financially support the start-up of all the proposed initiatives, from the most basic to the most productive” (E4). |

| Mindset | General vision of life (ideas and convictions). | “The mentality of the original people was that of being laborers, almost to the point of being slaves to the landowners. The impetus given by the Jesuit missionaries made it possible to strengthen community organizations, carrying out various projects with their objectives. It can be said that the seed achieved great milestones in social, educational, productive and environmental improvement” (E24). |

| Authority | The commune as the highest authority of a community. | “The commune is another important pillar. It is the one that calls for “mingas” (community work). It is the highest authority, and in some issues, it has more power than the Parish Council itself. Thanks to the power of the commune, the páramo reserve areas have been consolidated. It decides the release of areas for the reserve and the community accepts” (E16). |

| Organization | Creation of first, second and third order organizations. | “Although the indigenous organization has important strengths due to its traditional values such as solidarity and reciprocity, there were limitations in terms of visions of community development that were overcome with the support of various organizations” (E13). |

| Technical support and training | Technical assistance from government and private entities. National and international volunteers, interns, permanent talks and technical tours. | “Taking leaders from the area to see examples of protection of the páramo in other parts of the country has been a success in this conservation process, since they have been able to observe first-hand the benefits of protecting this ecosystem with patience” (E8). |

| Sustainability | The solidarity economy model allows company profits to be allocated to productive reinvestment, public works and expansion of opportunities for the inhabitants. | “FUNORSAL invests profits in giving environmental education talks and technical assistance to improve productivity, adding value to raw materials (…), supporting new initiatives such as llama meat sausages, which add to the cause of protecting the páramo” (E7). |

| Gender equality | Women are a fundamental pillar for the progress of communities | “Women are the ones who attend the meetings the most, and now, they have the power of opinion and a vote. They are the ones that support the mingas the most and are also invited to technical tours to other páramo areas. They are the ones that best understand the relationship between the páramo, water and crops, which is why they are already part of the water board directives” (E23). |

| Creativity | Ability to develop new economic alternatives. | “The greatest success achieved in generating alternatives, which is the inheritance of the Salesians, is the curiosity and drive to develop various product initiatives. Almost everyone knows how to make cheese, nougat and jam. This has allowed people to get ahead, even if they did not have the advantage of obtaining a more thorough academic education” (E1). |

| Reflection | Permanent dialogue that seeks understanding among all members of the community. | “Reflection Mondays are a strength, an opportunity to discuss and talk about the needs of the area, and everyone contributes and enriches the search for solutions to the various problems in the area” (E20). |

| Local knowledge | Technical and social proposals of native peoples. | “When reforestation activities are carried out, if the plants are native to the páramo, they are accepted; otherwise, the community rejects them” (E14). |

| Nature | Incredible biodiversity and magnificent landscapes open the door to ecological tourism. | “The younger generations observe that caring for the páramo has its advantages; sightings of wild animals and plants attract tourism” (E14). |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Torres, M.C.; Naranjo, E.; Fierro, V. Challenges Facing Andean Communities in the Protection of the Páramo in the Central Highlands of Ecuador. Sustainability 2023, 15, 11980. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151511980

Torres MC, Naranjo E, Fierro V. Challenges Facing Andean Communities in the Protection of the Páramo in the Central Highlands of Ecuador. Sustainability. 2023; 15(15):11980. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151511980

Chicago/Turabian StyleTorres, María Cristina, Efraín Naranjo, and Vanessa Fierro. 2023. "Challenges Facing Andean Communities in the Protection of the Páramo in the Central Highlands of Ecuador" Sustainability 15, no. 15: 11980. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151511980

APA StyleTorres, M. C., Naranjo, E., & Fierro, V. (2023). Challenges Facing Andean Communities in the Protection of the Páramo in the Central Highlands of Ecuador. Sustainability, 15(15), 11980. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151511980