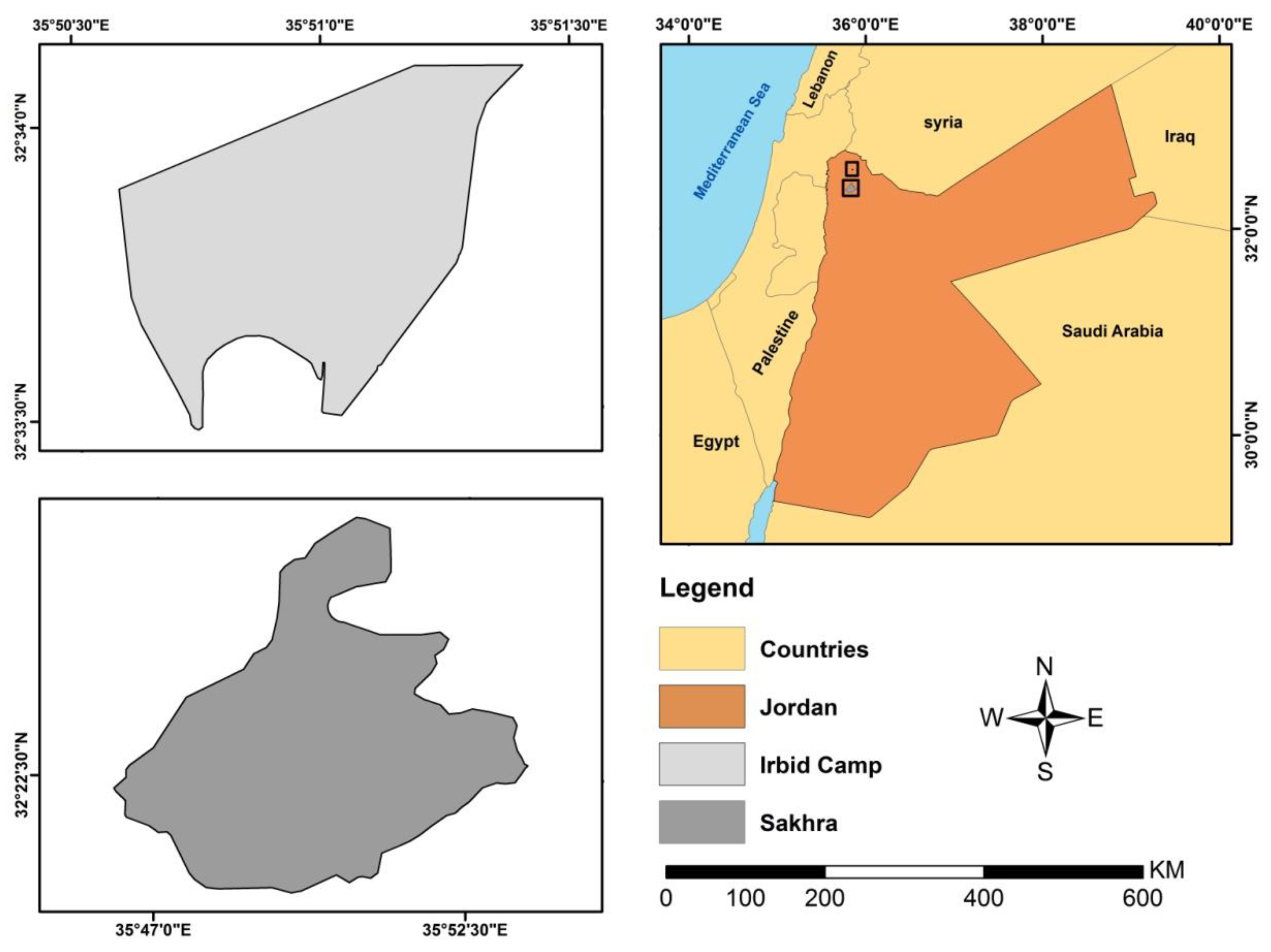

The study aimed to determine the overall preference among refugees for cultivated roofs, refrigerators as food banks, or their ideas for achieving zero hunger in the camps and vulnerable areas, specifically in the Irbid Camp and Sakhra region. The results show that 10% (26) of the refugees preferred cultivated roofs, while a significant majority, 90% (233), preferred refrigerators as food banks, with some refugees suggesting alternative ideas, such as opening a grocery store, a sewing lab for teaching and operation, a supermarket project, breeding, and rental of wedding and holiday supplies.

The lower preference for cultivated roofs (10%) can be attributed to various factors, including the unsuitability of the camp buildings’ roofs for cultivation, restrictions on roof usage in rented houses, lack of available land inside the camp, insufficient knowledge of roof cultivation among the refugees, marketing challenges for agricultural products, the expense of materials and equipment required for roof cultivation, and difficulties in storing agricultural products due to rapid deterioration.

On the other hand, most refugees (90%) preferred refrigerators as food banks due to this solution’s convenience, low risk, and cost-effectiveness, and the fact that it does not require specific skills and aligns with the community culture. Additionally, refrigerators have been successfully implemented in other locations worldwide. The key factors contributing to the preference for refrigerators as food banks include convenience and accessibility, food preservation capabilities, security, storage capacity, fostering a sense of independence among the refugees, and the potential for sustainability through renewable energy sources, such as solar power.

5.1. Detailed Descriptive Analysis

To determine the project preference among the refugees, an analysis was conducted to assess the receptiveness of the refugees towards the two proposed interventions; the results are presented in

Table 1. Based on these findings, it can be concluded that refrigerators as food banks (

) are the predominant preference among refugees for achieving zero hunger in the studied hunger and poverty regions. It is worth mentioning that there were some ideas from the refugees for achieving zero hunger in addition to the proposed ones (e.g., opening a grocery store, a sewing lab for teaching and operation, supermarket project, breeding, and rental of wedding and holiday supplies). Such ideas pave the road toward future research for achieving zero hunger in poverty pockets across Jordan.

The influence of the demographic factors, such as age, gender, education level, and family size, on refugee preferences for cultivated roofs, refrigerators as food banks, or their ideas for achieving zero hunger was investigated using various statistical tests. For the age attribute, no significant relationship was found between age and refugee acceptance of the cultivated roofs project nor the acceptance of refrigerators as food banks project. Such conclusions were extracted after testing the hypothesis in

Table 2 for the cultivated roofs (

) and the refrigerators as food banks (

). In both cases, the

was greater than the level of significance

, indicating the hull hypothesis (

) failed to be rejected, and there is no significant relationship between age and refugee acceptance of the cultivated roofs (

) and refrigerators as food banks (

) projects. Thus, the lack of preference for the cultivated roofs (

) and refrigerators as food banks (

) solutions was unrelated to the age attribute, suggesting that other variables may influence the two preferences.

For the gender and the family size attributes, no significant relationship was found between the gender and refugee acceptance of the cultivated roofs project, nor the acceptance of refrigerators as food banks project. Such conclusions were extracted after testing the cultivated roofs (

) and the refrigerators as food banks (

) hypothesis, as shown in

Table 3 and

Table 4. In both cases, the

p-value was greater than the level of significance

, indicating the hull hypothesis (

) failed to be rejected, and no significant relationship between gender or family size and refugee acceptance of the cultivated roofs (

) and refrigerators as food banks (

) projects exists. Thus, the lack of preference for the cultivated roofs (

) and refrigerators as food banks (

) solutions were unrelated to the gender or family size attribute, suggesting that other variables may influence the two preferences.

For the level of education attribute, no significant relationship was found between the level of education and refugee acceptance of the cultivated roofs project. Such conclusions were extracted after testing the hypothesis for the CRs, where the

p-value was greater than the level of significance

, indicating the hull hypothesis (

) failed to be rejected, and no significant relationship exists between the level of education and refugee acceptance of the CRs project. However, a significant relationship was found between the level of education and refugee acceptance of refrigerators as food bank projects. Such conclusions were extracted after testing the hypothesis for the RaFB, where the

was lower than the level of significance

, indicating the hull hypothesis was rejected, and there is a significant relationship between the level of education and refugee acceptance of the RaFB project. It was observed that refugees with higher educational levels were more likely to reject the solution to zero hunger by installing refrigerators as food banks. This might explain why the refugees with higher educational levels were more likely to reject the solution to achieving zero hunger by installing refrigerators as food banks. Refugees with higher educational levels may have different cultural beliefs, values, or expectations than those with lower educational levels. They may also have different perceptions of the effectiveness or practicality of the proposed solution. Alternatively, it could be due to socio-economic status, prior experiences with similar interventions, or access to alternative solutions. Further research would be necessary to better understand the factors influencing the acceptance or rejection of the proposed solution by refugees with varying educational levels.

Table 5 represents the hypothesis testing results for the level of education attribute with the two proposed projects.

The results obtained from the survey shed light on the potential benefits of implementing an project, including (1) reduced food waste because refrigerators can help to preserve perishable food items, minimizing waste and ensuring that available food resources are used effectively; (2) improved food security by providing a secure location for food storage, as refrigerators can reduce the risk of theft or spoilage, enhancing overall food security in the poverty pocket regions; (3) enhanced nutrition, as access to refrigerated storage can encourage refugees to consume a more diverse range of fresh and nutritious food items, contributing to better overall health and well-being; (4) promoting self-reliance because refrigerators can empower refugees to manage their own food resources, fostering a sense of autonomy and independence; (5) scalability, as refrigerators can be easily scaled up or down depending on the needs of the refugee population, making them a flexible solution to food storage challenges; and (6) achieving environmental sustainability via the utilization of renewable energy sources, such solar power, refrigerators can provide a sustainable and environmentally friendly option for food storage in refugee camps.

In addition, the obtained results can be considered a solid foundation for determining the potential challenges of implementing the project, including (1) limited access to electricity, as many refugee camps face challenges in accessing reliable electricity sources, which could hinder the effective use of refrigerators as food banks; (2) cost and maintenance, as the initial cost of purchasing refrigerators and ongoing maintenance expenses can be significant, potentially limiting the feasibility of implementing this solution in some contexts; (3) cultural acceptance, where the acceptability of using refrigerators as food banks may vary across different cultural contexts, potentially impacting the success of the intervention; (4) logistics and transportation, as the transportation and installation of refrigerators in refugee camps may pose logistical challenges, particularly in remote or difficult-to-reach locations; (5) coordination and management, as the effective operation of refrigerators as food banks may require robust coordination and management systems to ensure equitable access to food resources and prevent misuse or abuse of the intervention; and (6) security concerns, as ensuring the security of the refrigerators and their contents may require additional resources and planning, particularly in contexts where theft or vandalism is a concern.

5.2. Probit and Logistic Regression

In this sub-section, we investigate deeper into the determinants of intervention preferences by employing two widely used techniques in the realm of econometrics: probit and logistic regression. Despite their similar purposes, these two methods offer unique insights and advantages, allowing us to analyze the variables influencing refugee households’ intervention preferences comprehensively. Probit and logistic regression are particularly useful for examining binary outcomes, as with our interventions, where the response of interest is the household’s preference for an intervention, expressed as a binary choice. Through these methods, we aim to quantify the relationship between the predictor variables, including household demographics, characteristics, and amenities, and the probability of a household opting for a given intervention. This approach will deepen our understanding of the factors influencing the refugees’ preferences, thereby guiding more effective intervention strategies.

The subsequent tables (i.e.,

Table 6,

Table 7,

Table 8 and

Table 9) encapsulate the results of our probit and logistic regression models for each intervention. These tables include the essential statistical parameters, including the coefficients, standard errors (s.e.), Wald’s test,

, odds ratios (

), and confidence intervals (lower and upper). The coefficients (or beta values) indicate the magnitude and direction of the relationship between each independent variable and the dependent variable, i.e., the likelihood of a household opting for a specific intervention. The standard errors and Wald’s test provide us with information about the reliability of these coefficients. The

then allow us to test these relationships statistically. The odds ratios provide a more intuitive understanding of the results by expressing the change in odds for a one-unit change in the predictor variables. The confidence intervals offer a range within which we can be reasonably confident that the true parameter lies. Together, these measures provide a robust foundation for understanding the determinants of intervention preferences.

As shown in

Table 6, the probit regression results for the refrigerators as food banks (RaFB) intervention suggest a complex relationship between the variables. The location, coded as Irbid Camp or Sakhra, has a coefficient of −0.012. This value and a high

p-value of 0.957 suggest that the location has no statistically significant effect on the outcome. The nationality variable also seems to have no significant effect, given its high

p-value (0.905). The house area-related variable has a negative coefficient (−1.590), indicating a negative relationship with the intervention’s outcome. However, the high

p-value (0.209) again implies that this effect is not statistically significant. It is worth mentioning that taking logarithms for certain variables was vital to remove the unit effects.

The variable house material-related variable is coded as either concrete or blocks. Its coefficient of −0.649 suggests that a shift from concrete to blocks is associated with a decrease in the dependent variable, suggesting that those living in houses made of blocks are less likely to adopt the RaFB intervention. The p-value of 0.7017 confirms the statistical insignificance of this relationship. Interestingly, the house ownership-related variable has a large positive coefficient of 4.486, yet it is statistically insignificant due to a very high p-value of 0.689, implying that the relationship might be due to chance.

The educational level-related variable has a notable negative coefficient of −0.931 and an extremely low p-value (2.548 × 10−7), indicating a strong statistically significant negative relationship. This could imply that as the level of education increases, the likelihood of adopting the RaFB intervention decreases. However, given the complexity of this relationship, this result should be further investigated for potential confounding factors. Such results match the descriptive statistical findings illustrated in the previous section.

The variable related to the educational level showed a statistically significant negative relationship with adopting the intervention in the regression analysis. This contrasts with the descriptive analysis, which highlighted the potential importance of education but did not indicate a clear negative relationship. Notably, the higher the education level, the lower the likelihood of adopting the ‘refrigerators as food banks’ intervention. This counter-intuitive result could be further investigated and interpreted in light of other socio-economic factors.

Many variables in the probit regression, such as location, nationality, house-related characteristics, and demographic characteristics (e.g., age and gender), did not have statistically significant effects. This partly aligns with the descriptive analysis, which did not highlight these factors as critical in adopting the intervention. However, the regression analysis allows for more precise estimates of these effects’ size and significance, reinforcing the descriptive analysis’s understanding. These comparisons underscore the complementary roles of descriptive and regression analysis in understanding the complex factors influencing the adoption of the ‘refrigerators as food banks’ intervention. They both shed light on different aspects of the relationships and provide a comprehensive overview of the situation.

Table 7 illustrates that the logistic regression analysis results provide insightful details on how various factors influence the adoption of refrigerators as food bank interventions. The most significant predictor is education, as demonstrated by its strong negative coefficient and extremely small

p-value, which suggests that with each additional level of education, the odds of adopting the refrigerator as a food bank intervention decrease. This is a compelling finding and might suggest that individuals with higher education levels may have other means of securing food, lessening their reliance on refrigerators as food banks. However, this is merely an interpretation and further investigation would be needed to understand the causal mechanisms involved.

Conversely, the variable related to the roof’s suitability for cultivation was found to be a positive predictor, although not statistically significant, suggesting a potential trend that families with roofs suitable for cultivation might be more inclined to adopt the intervention. The notion here could be that families who can cultivate their roofs might be more concerned with food security, hence also more likely to use refrigerators as food banks.

Interestingly, many of the other factors (including location, nationality, house material, house area, gender, and age) were not found to be significant predictors in the logistic regression model, which might suggest that adopting the refrigerator as a food bank intervention transcends these individual and demographic factors, being more influenced by socio-economic factors (i.e., education). However, it is important to remember that these findings are based on the available data and model specification and may not capture all the complexities and nuances of the intervention adoption process.

Table 8 represents the probit regression analysis of the cultivated roofs intervention, provides valuable insight, and reveals some significant findings. The analysis results show that the location significantly impacts choosing the CRs intervention, as the Sakhra Region relies more on cultivation when compared to the Irbid Camp. In addition, the house’s structural characteristics are more suitable for the CRs intervention. Moreover, the average roof area is larger. Additionally, the location, specifically the Irbid Camp or Sakhra, has influenced the adoption of the intervention due to different environmental conditions or community attitudes towards such initiatives.

The study further elucidates patterns that validate and diverge from the preceding qualitative analysis. The variable ‘House Material’ emerged as a significant determinant in the probit regression for the acceptance of (CRs) initiatives. This outcome aligns with the preliminary analysis, which inferred that the housing material could significantly influence the decision to implement rooftop cultivation. Block-built houses are typically not engineered to tolerate the weight and permeability associated with rooftop soil; hence, occupants of such dwellings may be disinclined to embrace CRs methods due to the increased likelihood of water seepage and roof degradation when the rooftop is used for cultivation. While the regression paints a more complex picture, it suggests that individuals residing in block-made houses are less likely to opt for the intervention.

The age variable and its square also showed lower statistical significance. Interestingly, the sign of the coefficient is negative, suggesting that the probability of adopting the cultivated roofs intervention decreases as age increases. This finding may be understood in that older individuals may have less propensity or ability to manage a cultivated roof due to potential physical limitations. However, it is essential to note that the squared term of age, which could capture non-linear effects, was not found to be statistically significant.

The variable ‘Roof Suitability for Cultivation’ stands out with a significant positive coefficient, suggesting that as the roof’s suitability for cultivation increases, the likelihood of adopting the cultivated roof intervention also significantly increases. This result is expected, considering that having a roof that is more suitable for cultivation naturally facilitates the implementation of such an intervention.

Many of the variables in the regression (e.g., nationality and house area) were statistically insignificant. This suggests that these factors do not significantly influence the adoption of the cultivated roofs intervention. Such regression analysis helps understand the variables influencing the implementation of the cultivated roofs intervention, highlighting the critical role of roof suitability for cultivation and, to a lesser extent, age and location. The findings provide an empirical basis for targeted strategies to promote the adoption of this intervention.

Drawing on the results of the descriptive analysis conducted earlier, it is interesting to note how they compare and contrast with the outcomes from the probit regression model for the cultivated roofs intervention. The descriptive analysis pointed to the importance of the house area and the availability of certain amenities, such as a refrigerator, cooker, and microwave, in determining the living conditions of the individuals. However, the regression analysis did not find these variables significant predictors for adopting the cultivated roofs intervention. It suggests that while these factors may be crucial for understanding the general living conditions, they might not directly relate to the decision to adopt this specific intervention.

Interestingly, the regression analysis underscored the roofs’ suitability for cultivation variable as a highly significant factor influencing the adoption of the intervention, which aligns well with the descriptive findings, wherein a visible correlation was noted between the suitability of roofs for cultivation and the likelihood of their use for such purposes. On the subject of age, while the descriptive analysis might not have directly implied its importance, the regression analysis highlighted its role, although it is not as crucial as roof suitability. The inverse relationship between age and the adoption of the cultivated roofs intervention is an interesting finding that was not apparent in the initial descriptive analysis.

The location factor, which seemed to contribute to the living conditions in the descriptive analysis, was also significant in the regression analysis. This shows that the living environment, determined partly by the location, might play a role in adopting the intervention. The comparison and connection of these two analyses provide a nuanced understanding of the factors influencing the adoption of the cultivated roofs intervention. The blend of descriptive and regression analyses gives a more rounded view, emphasizing the complexity of the decision-making processes underlying such interventions.

The logistic regression analysis for the cultivated roofs (CRs) intervention, as shown in

Table 9, provides clear insight into the factors affecting the adoption of this intervention. A critical finding from the analysis is the significance of ‘Roof Suitability for Cultivation’ as a positive predictor of CRs intervention adoption. Its large coefficient and small

p-value (almost zero) suggest that as the roof’s suitability for cultivation increases, so does the likelihood of CRs intervention adoption. This result aligns with intuitive expectations, as families with roofs more suitable for cultivation would naturally be more inclined to implement the CRs intervention.

Location, specifically, whether the household is located in the Irbid Camp or Sakhra, positively impacts the adoption of the CRs intervention, albeit at the border of statistical significance (p-value of 0.0502). This suggests a slight trend that families in one location might be more inclined to adopt the CRs intervention than those in the other. However, this finding should be interpreted cautiously, given the marginal significance level. In addition, an interesting observation is the age variable’s negative but significant effect. It suggests that as the age of the head of household increases, the likelihood of adopting the CRs intervention decreases. It might be that younger households are more open to adopting new interventions or are more aware of and concerned with environmental issues.

Contrarily, many factors, such as housing materials, house ownership, monthly house rental, and education, do not appear to influence the adoption of the CRs intervention significantly. This indicates that adopting the CRs intervention transcends these individual and socio-economic factors and is more influenced by practical considerations (such as house material and roof suitability) and demographic factors (e.g., age and location). As always, while the results provide strong evidence, they should be interpreted in the context of the data and methodology used and with the understanding that the reality might be more complex.

For the RaFB intervention, the probit and logistic regression models show some similarities and notable differences. Both models suggest that education is a significant predictor for adopting this intervention, with education being both negatively and positively related. This indicates that households with lower education levels are more likely to adopt the intervention, according to both models. However, the statistical significance of the refrigerator’s availability is a key discrepancy between the two models. The probit model shows a positive relationship with the adoption of the intervention, whereas the logistic regression model shows a negative but not statistically significant relationship.

Turning to the CRs intervention, the probit and logistic regression analyses highlight the roof’s suitability for cultivation and the type of housing material as a strong and positive predictor of intervention adoption. The location variable also emerged as significant in both models, but with opposing effects: while the probit model shows a positive effect, the logistic regression model has a negative coefficient. Age is another variable with inconsistent results across the models. The probit model indicates a negative relationship between age and the likelihood of adopting the intervention, but the variable is not significant in the logistic regression model. On the other hand, variables such as house ownership and monthly house rental do not appear to significantly influence the adoption of the CRs intervention in either model.

While the probit and logistic regression models for each intervention share some common findings, they also present some discrepancies. These discrepancies might be due to the underlying differences in the assumptions and functional forms of the two models; therefore, it’s crucial to consider the context, research question, and data characteristics when choosing and interpreting regression models.

A comparison with the previous logistic regression analysis for the refrigerators as food banks intervention shows similar and contrasting patterns. For instance, house material was a significant factor for the refrigerators as food banks intervention but appeared to have no significant impact on the CRs intervention. Conversely, the age factor was not significant in the previous analysis, but is significant here, highlighting the importance of considering different factors when planning and implementing different types of interventions. It also underscores the value of performing multiple analyses to better understand the unique factors influencing the success of each intervention.

The receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve is a graphical plot that represents the diagnostic ability of a binary classifier system as its discrimination threshold is varied. The curve is created by plotting the true positive rate (TPR), also known as the sensitivity, recall, or hit rate, against the false positive rate (FPR), the fall-out or probability of false alarm, at various threshold settings. The TPR is plotted on the y-axis and represents the proportion of actual positives (e.g., households adopting a specific intervention) that are correctly identified as such. On the other hand, the FPR is plotted on the x-axis and denotes the proportion of actual negatives (e.g., households not adopting the intervention) that are incorrectly identified as positives. The area under the ROC curve, or AUC, measures how well a parameter can distinguish between two diagnostic groups (diseased/normal or adopter/non-adopter). A model whose predictions are 100% correct has an AUC of 1, while a model with no better than random chance has an AUC of 0.5; hence, the closer the curve follows the left-hand border and then the top border of the ROC space, the more accurate the test. It is worth noting that the ROC curve does not depend on the class distribution, making it a popular choice for evaluating the performance of machine learning models, especially in scenarios where there are imbalanced classes. The receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves for the probit and logistic regression for each intervention are shown in

Figure 4.

Drawing comparisons between the results of the probit regression analysis and the descriptive analysis can offer valuable insight into the intricacies of the study. The descriptive statistics provided initial insight into the preferences of refugees for the refrigerators as food banks (RaFB) intervention over cultivated roofs (CRs). It reported that a substantial majority (90%) preferred RaFB, indicating a clear leaning toward this intervention.

The probit regression analysis further deepened our understanding of these preferences by quantifying the influence of various factors. It confirmed some of the findings from the descriptive analysis but also provided new insight. For instance, the descriptive analysis showed no significant influence of the demographic factors, such as age, gender, and household size, on the acceptance of the interventions. This was also echoed in the probit regression, where these variables proved statistically insignificant, signifying that they did not significantly impact the preference for RaFB.

In contrast, the education variable, seen as a significant factor influencing the acceptance of RaFB in the descriptive analysis, was also found to be significant in the probit model but with a negative coefficient, which implies that the likelihood of preferring RaFB decreases as the education level increases. This complements the finding from the descriptive analysis that those with higher education levels were more likely to reject RaFB. Furthermore, variables such as house materials that were not explicitly highlighted in the descriptive analysis were found to significantly influence the preference for RaFB in the probit model. The negative coefficient suggests that a shift in house material from traditional to modern decreases the preference for RaFB, providing a nuanced understanding that was not clear from the descriptive analysis alone.

While the descriptive analysis provides a broad overview of the refugees’ preferences, the probit regression adds depth by quantifying the impacts of various factors and highlighting potential areas for intervention to increase the acceptance of RaFB. These findings provide a more robust basis for policy recommendations, offering key insight into which factors might need to be addressed to increase the adoption of the preferred RaFB intervention.

Looking back at the previously stated results from the descriptive analysis, the regression results largely align with these while also providing nuance and depth. In the descriptive analysis, we established that a significant portion of refugees indicated a preference for the cultivated roofs (CR) intervention. The regression analysis affirmed this and went a step further to identify the factors that drive this preference. Particularly, the suitability of a roof for cultivation emerged as a strong determinant in the regression analysis, which resonates with the descriptive analysis’ finding of the high acceptability of the CR intervention.

The age factor showed an interesting dynamic. While the descriptive analysis observed a wide range of ages among the refugees preferring the CRs intervention, the regression analysis revealed that the likelihood of preferring CRs decreases as age increases. This suggests that while a broad age group may favor the CRs intervention, it is more popular among younger individuals. Household characteristics, such as the house type, material, area, and appliances (refrigerator, cooker, microwave), were insignificant in the regression analysis, which mirrors the descriptive analysis, which did not highlight any particular patterns concerning these variables. It seems that the preference for CRs is largely independent of these factors. Contrastingly, while the descriptive analysis revealed different preferences for the CRs intervention among various nationalities, the regression analysis suggested that nationality does not have a significant effect. This discrepancy might be due to the high standard error and p-value associated with the nationality variable in the regression model. More investigation may be needed to resolve this inconsistency. In addition, the regression and descriptive analyses offer complementary insight into refugee preferences for the CRs intervention. While the descriptive analysis provides an overall picture, the regression analysis digs deeper into the specific factors influencing these preferences.

Several key trends emerged in synthesizing the findings across the descriptive analysis, probit regression, and logistic regression for both interventions. For the refrigerators as food banks intervention, the descriptive analysis indicated that the number of household members, education, and house materials were important factors, which was generally supported by the probit and logistic regression analyses, with the education and house material variables emerging as significant. Despite this, differences in the results across the analyses—for instance, the marital status factor was significant in the logistic regression but not in probit—illustrate the complexity of determining intervention preferences and the importance of considering different analytical perspectives.