Acceptance Factors for the Social Norms Promoted by the Community-Led Total Sanitation (CLTS) Approach in the Rural Areas: Case Study of the Central-Western Region of Burkina Faso

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

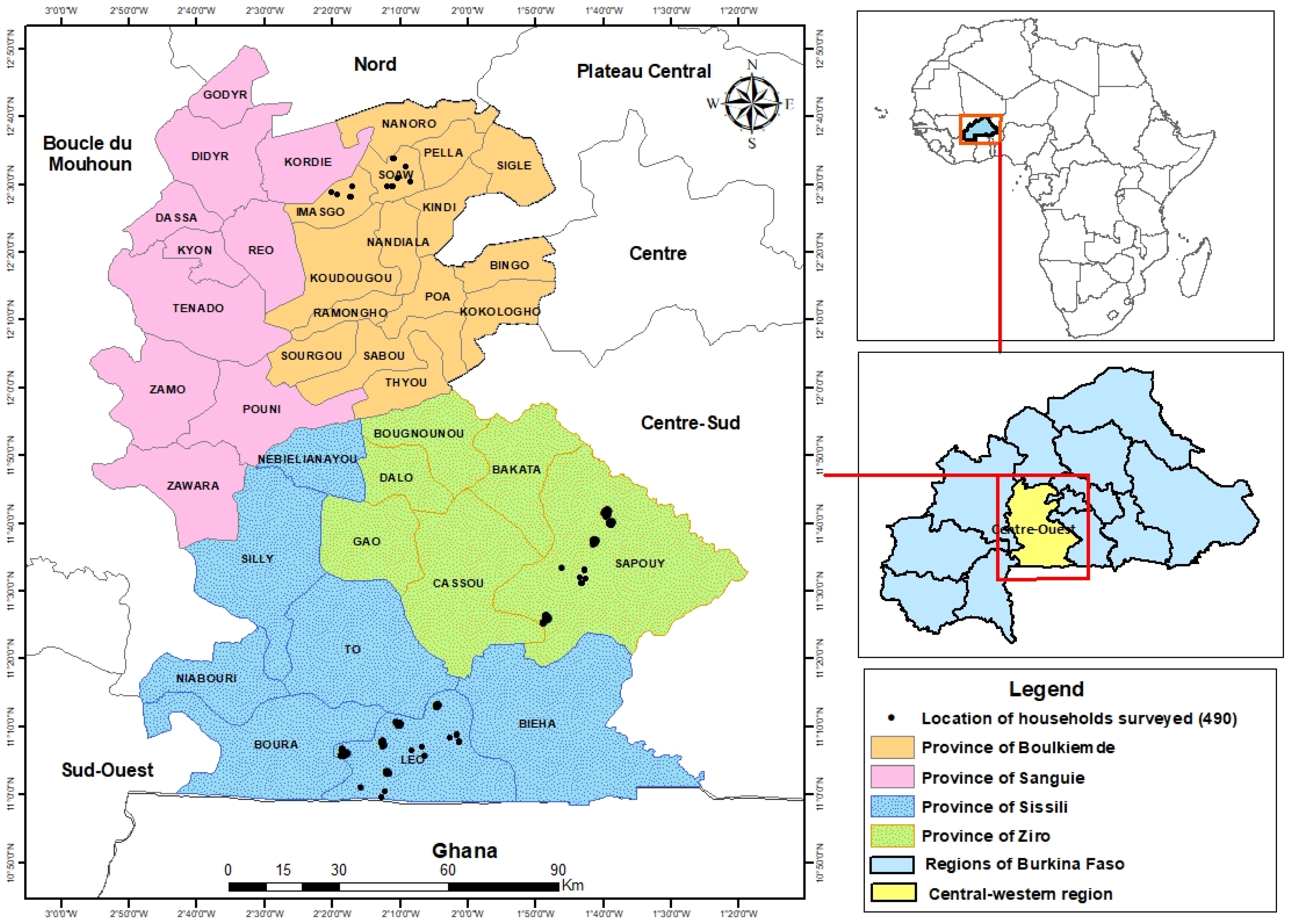

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Sampling

2.3. Ethical Considerations

2.4. Study Design

2.5. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Governance Factors

3.1.1. Institutional Triggering of CLTS

3.1.2. Commitment of Natural Leaders

3.1.3. Promises during CLTS Triggering

3.1.4. Good Communication of the Message Conveyed by CLTS Approach in the Local Language

3.1.5. Experience of CLTS Facilitators and Animators

3.1.6. Entering the Target Community for CLTS Triggering with a Team That Does Not Have a History of Conflict with the Community

3.1.7. Presence of Representatives of the Ministries and Authorities on the Day of CLTS Triggering and Intervention of the High Commissioner and Administrative Officials for Mediation

3.1.8. Sharing of CLTS Experiences and Success by Natural Leaders

3.2. Environmental Factors

Understanding the Health and Economic Consequences of OD

3.3. Territorial Factors

3.3.1. Popularity and Reputation of ODF-Certified Villages

3.3.2. Same Type of Approach Taken in Surrounding Communities

3.4. Economic Factors

Projected Increase in Revenue and Demand for Skills and Materials for Latrine Construction

3.5. Social Factors

3.5.1. Natural Rivalry between Villages Located in the Same Geographical Area

3.5.2. Women’s Understanding of the Adverse Effects of OD on Their Children’s Health

3.5.3. Men’s Desire to Protect Their Wives’ Privacy

3.5.4. Social Pressure from One Group on Another Group or an Individual

3.5.5. No or Very Few Internal Cohesion or Chieftaincy Problems

3.5.6. Social and Cultural Beliefs

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- UN ‘Transformational Benefits’ of Ending Outdoor Defecation: Why Toilets Matter|UN DESA|United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs. Available online: https://www.un.org/development/desa/en/news/sustainable/world-toilet-day2019.html (accessed on 1 June 2022).

- Galan, D.I.; Kim, S.-S.; Graham, J.P. Exploring Changes in Open Defecation Prevalence in Sub-Saharan Africa Based on National Level Indices. BMC Public Health 2013, 13, 527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- JMP Progress on Household Drinking Water, Sanitation and Hygiene 2000–2020: Five Years into the SDGs. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications-detail-redirect/9789240030848 (accessed on 27 May 2022).

- Zuin, V.; Delaire, C.; Peletz, R.; Cock-Esteb, A.; Khush, R.; Albert, J. Policy Diffusion in the Rural Sanitation Sector: Lessons from Community-Led Total Sanitation (CLTS). World Dev. 2019, 124, 104643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Institute of Development Studies The CLTS Approach 2019. Available online: http://www.communityledtotalsanitation.org/page/clts-approach (accessed on 11 January 2021).

- Kar, K.; Chambers, R. Handbook on Community-Led Total Sanitation; Plan International: Surrey, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Kouassi, H.A.A.; Andrianisa, H.A.; Traoré, M.B.; Sossou, S.K.; Momo Nguematio, R.; Ymélé, S.S.S.; Ahossouhe, M.S. Review of the Slippage Factors from Open Defecation-Free (ODF) Status towards Open Defecation (OD) after the Community-Led Total Sanitation (CLTS) Approach Implementation. Int. J. Hyg. Environ. Health 2023, 250, 114160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abebe, T.A.; Tucho, G.T. Open Defecation-Free Slippage and Its Associated Factors in Ethiopia: A Systematic Review. Syst. Rev. 2020, 9, 252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bongartz, P.; Vernon, N.; Fox, J. Sustainable Sanitation for All: Experiences, Challenges and Innovations; Practical Action: Rugby, UK, 2016; ISBN 9781853399275. [Google Scholar]

- Crocker, J.; Saywell, D.; Bartram, J. Sustainability of Community-Led Total Sanitation Outcomes: Evidence from Ethiopia and Ghana. Int. J. Hyg. Environ. Health 2017, 220, 551–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delaire, C.; Kisiangani, J.; Stuart, K.; Antwi-Agyei, P.; Khush, R.; Peletz, R. Can Open-Defecation Free (ODF) Communities Be Sustained? A Cross-Sectional Study in Rural Ghana. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0261674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Odagiri, M.; Muhammad, Z.; Cronin, A.A.; Gnilo, M.E.; Mardikanto, A.K.; Umam, K.; Asamou, Y.T. Enabling Factors for Sustaining Open Defecation-Free Communities in Rural Indonesia: A Cross-Sectional Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2017, 14, 1572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Tyndale-Biscoe; Bond, M.; Kidd, R. Plan International ODF Sustainability Study; Community-Led Total Sanit: Brighton, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Abdi, R. Open Defecation Free Sustainability Study in East Timor 2015–2016; Water Aid: Dili, East Timor, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Barnard, S.; Routray, P.; Majorin, F.; Peletz, R.; Boisson, S.; Sinha, A.; Clasen, T. Impact of Indian Total Sanitation Campaign on Latrine Coverage and Use: A Cross-Sectional Study in Orissa Three Years Following Programme Implementation. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e71438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bhatt, N.; Budhathoki, S.S.; Lucero-Prisno, D.E.I.; Shrestha, G.; Bhattachan, M.; Thapa, J.; Sunny, A.K.; Upadhyaya, P.; Ghimire, A.; Pokharel, P.K. What Motivates Open Defecation? A Qualitative Study from a Rural Setting in Nepal. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0219246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osumanu, I.K.; Kosoe, E.A.; Ategeeng, F. Determinants of Open Defecation in the Wa Municipality of Ghana: Empirical Findings Highlighting Sociocultural and Economic Dynamics among Households. J. Environ. Public Health 2019, 2019, 3075840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Patwa, J.; Pandit, N. Open Defecation-Free India by 2019: How Villages Are Progressing? Indian J. Community Med. Off. Publ. Indian Assoc. Prev. Soc. Med. 2018, 43, 246–247. [Google Scholar]

- Pendly, C.; Obiols, A.L. Learning from Innovation: One Million Initiative in Mozambique, Community-Led Total Sanitation Case Study; IRC Centre International de l’eau et de l’assainissement: La Haye, The Netherlands, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Godfrey, S.; Van der Velden, M.; Muianga, A.; Xavier, A.; Downs, K.; Morgan, C.; Bartram, J. Sustainability Check: Five-Year Annual Sustainability Audits of the Water Supply and Open Defecation Free Status in the ‘One Million Initiative’, Mozambique. J. Water Sanit. Hyg. Dev. 2014, 4, 471–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- INSD Cinquième Recensement Général de La Population et de l’Habitation Du Burkina Faso. Fichier Des Localités Du 5e RGPH. Available online: https://burkinafaso.opendataforafrica.org/smuvohd/r%C3%A9sultats-pr%C3%A9liminaires-du-5e-rgph-2019 (accessed on 2 June 2022).

- Lwanga, S.K.; Lemeshow, S. World Health Organization Sample Size Determination in Health Studies: A Practical Manual/S. K. Lwanga and S. Lemeshow; D’ermination Taille Un Čhantillon Dans Ťudes Sanomťriques Man: Prat, France, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Dussaix, A.-M. La Qualité Dans Les Enquêtes. Rev Modul. 2009, 39, 137–171. [Google Scholar]

- Hoffmeyer-Zlotnik, J.H. New Sampling Designs and the Quality of Data. Dev. Appl. Stat. 2003, 19, 205–217. [Google Scholar]

- Terrade, F.; Pasquier, H.; Reerinck-Boulanger, J.; Guingouain, G.; Somat, A. L’acceptabilité sociale: La prise en compte des déterminants sociaux dans l’analyse de l’acceptabilité des systèmes technologiques. Trav. Hum. 2009, 72, 383–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boissonade, J.; Barbier, R.; Bauler, T.; Fortin, M.-J.; Fournis, Y.; Lemarchand, F.; Raufflet, E. Mettre à l’épreuve l’acceptabilité Sociale. VertigO-Rev. Électron. Sci. Environ. 2016, 16, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Environnement, T. Étude Sur Les Facteurs Pouvant Influencer L’acceptabilité Sociale des Équipements de Traitement des Matières Résiduelles; Communauté Métropolitaine de Montréal, Planification de la Gestion des Matières Résiduelles: Montreal, QC, Canada, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Fortin, M.-J.; Fournis, Y.; Beaudry, R. Acceptabilité Sociale, Énergies et Territoires: De Quelques Exigences Fortes Pour l’action Publique. Mém. Soumis À Comm. Sur Enjeux Énergétiques 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fortin, M.-J.; Fournis, Y. L’acceptabilité Sociale de Projets Énergétiques Au Québec: La Difficile Construction Par l’action Publique; Erudit: Montreal, QC, Canada, 2011; pp. 321–331. [Google Scholar]

- Fournis, Y.; Fortin, M.-J. From Social ‘Acceptance’ to Social ‘Acceptability’ of Wind Energy Projects: Towards a Territorial Perspective. J. Environ. Plan. Manag. 2017, 60, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fournis, Y.; Fortin, M.-J. Conceptualiser l’acceptabilité Sociale: La Force d’une Notion Faible. Sci. Territ. 2014, 2, 17–33. [Google Scholar]

- Fournis, Y.; Fortin, M.-J. L’acceptabilité Sociale de l’énergie Éolienne: Une Définition. Doc. Trav. 2013, 131017. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/283083591_L’acceptabilite_sociale_de_l’energie_eolienne_une_definition (accessed on 4 November 2022).

- DGAEUE Guide d’orientation Pour La Mise En Oeuvre de L’assainissement Total Pilote Par Les Communautés-ATPC Au BURKINA FASO, 155p. Available online: https://www.pseau.org/outils/ouvrages/dgaeue_unicef_guide_d_orientation_pour_la_mise_en_oeuvre_de_l_assainissement_total_pilote_par_la_communaute_au_burkina_faso_2014.Pdf2014 (accessed on 4 November 2022).

- Krippendorff, K. Reliability in Content Analysis: Some Common Misconceptions and Recommendations. Hum. Commun. Res. 2004, 30, 411–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krippendorff, K. Content Analysis: An Introduction to Its Methodology, 2nd ed.; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Neuendorf, K.A. The Content Analysis Guidebook Second Edition; USA Cleveland State University: Cleveland, OH, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Berelson, B. Content Analysis in Communication Research; Content Analysis in Communication Research; Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 1952. [Google Scholar]

- Musembi, C.N.; Musyoki, S.M. « L’ATPC et Le Droit à l’assainissement », Aux Frontières de l’ATPC: Innovations et Impressions, 8, Brighton: IDS. 2016. Available online: www.Communityledtotalsanitation.Org/Resources/Frontiers/l-Atpc-et-Le-Droit-l-Assainissement (accessed on 11 December 2021).

- Hanchett, S.; Krieger, L.; Kahn, M.H.; Kullmann, C.; Ahmed, R. Long-Term Sustainability of Improved Sanitation in Rural Bangladesh; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- UN. Women Menstrual Hygiene Management: Behaviour and Practices in the Louga Region; UN: Dakar, Senegal, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- ID4D. Ideas4development the Unexpected Link between Access to Toilets and Women’s Rights. 2019. Available online: https://ideas4development.org/en/unexpected-link-access-toilets-womens-rights/ (accessed on 9 February 2022).

- OXFAM Accès Aux Toilettes: À Travers Le Monde, Des Réalités Bien Différente. 2021. Available online: https://www.oxfamfrance.org/humanitaire-et-urgences/acces-aux-toilettes-et-latrines-dans-le-monde/ (accessed on 14 March 2023).

- Prüss-Üstün, A.; Wolf, J.; Corvalán, C.; Bos, R.; Neira, M. Preventing Disease through Healthy Environments: A Global Assessment of the Burden of Disease from Environmental Risks; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2016; ISBN 9241565195.

- Walker, C.L.F.; Rudan, I.; Liu, L.; Nair, H.; Theodoratou, E.; Bhutta, Z.A.; O’Brien, K.L.; Campbell, H.; Black, R.E. Global Burden of Childhood Pneumonia and Diarrhoea. Lancet 2013, 381, 1405–1416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, L.; Johnson, H.L.; Cousens, S.; Perin, J.; Scott, S.; Lawn, J.E.; Rudan, I.; Campbell, H.; Cibulskis, R.; Li, M. Global, Regional, and National Causes of Child Mortality: An Updated Systematic Analysis for 2010 with Time Trends since 2000. Lancet 2012, 379, 2151–2161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Routray, P.; Schmidt, W.-P.; Boisson, S.; Clasen, T.; Jenkins, M. Socio-Cultural and Behavioural Factors Constraining Latrine Adoption in Rural Coastal Odisha: An Exploratory Qualitative Study. BMC Public Health 2015, 15, 880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- WHO. Lignes Directrices Relatives à L’assainissement et à La Santé; Guidelines on Sanitation and Health: Genève, Switzerland, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Hulland, K.; Martin, N.; Dreibelbis, R.; Valliant, J.D.; Winch, P. What Factors Affect Sustained Adoption of Safe Water, Hygiene and Sanitation Technologies? A Systematic Review of Literature; EPPI-Centre, Social Science Research Unit, UCL Institute of Education, University College London: London, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavill, S.; Chambers, R.; Vernon, N. Sustainability and CLTS: Taking Stock; IDS: London, UK, 2015; ISBN 9781781182222. [Google Scholar]

- Wilbur, J.; Jones, H. Handicap: Rendre l’ATPC Véritablement Accessible à Tous. Aux Front. L’ATPC Innov. Impr. 2014, 3, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Harter, M.; Mosch, S.; Mosler, H.-J. How Does Community-Led Total Sanitation (CLTS) Affect Latrine Ownership? A Quantitative Case Study from Mozambique. BMC Public Health 2018, 18, 387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novotný, J.; Kolomazníková, J.; Humňalová, H. The Role of Perceived Social Norms in Rural Sanitation: An Explorative Study from Infrastructure-Restricted Settings of South Ethiopia. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2017, 14, 794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Robinson, A.; Bond, M.; Kidd, R.; Mott, J.; Tyndale-Biscoe, P. Final Evaluation: Pan African CLTS Program 2010–2015; Plan Nethwork: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Baba, S.; Raufflet, E. L’acceptabilité Sociale: Une Notion En Consolidation. Manag. Int. Manag. Int. 2015, 19, 98–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Fazio, R.; Zanna, M. Direct Experience And Attitude-Behavior Consistency. In Advances in Experimental Social Psychology; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1981; Volume 14, pp. 161–202. ISBN 9780120152148. [Google Scholar]

- Glasman, L.; Albarracin, D. Forming Attitudes That Predict Future Behavior: A Meta-Analysis of the Attitude–Behavior Relation. Psychol. Bull. 2006, 132, 778–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Fishbein, M.; Ajzen, I. Belief, Attitude, Intention, and Behavior: An Introduction to Theory and Research; Addison-Wesley: Reading, MA, USA, 1977; p. 10. [Google Scholar]

- LaCaille, L. Theory of Reasoned Action. In Encyclopedia of Behavioral Medicine; Gellman, M.D., Turner, J.R., Eds.; Springer New York: New York, NY, USA, 2013; pp. 1964–1967. ISBN 978-1-4419-1005-9. [Google Scholar]

- Eagly, A.H.; Chaiken, S. The Psychology of Attitudes; Harcourt Brace Jovanovich College Publishers: New York, NY, USA, 1993; ISBN 0155000977. [Google Scholar]

- Ajzen, I. From Intentions to Actions: A Theory of Planned Behavior. In Action Control; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1985; pp. 11–39. [Google Scholar]

- Beauvois, J.-L.; Ghiglione, R.; Joule, R.-V. Quelques Limites Des Réinterprétations Commodes Des Effets de Dissonance. Bull. Psychol. 1976, 29, 758–765. [Google Scholar]

- Beauvois, J.-L.; Joule, R.-V.; Monteil, J.-M. Social Regulation and Individual Cognitive Function: Effects of Individuation on Cognitive Performance. Eur. J. Soc. Psychol. 1991, 21, 225–237. [Google Scholar]

- CPEQ. Conseil patronal de l’environnement du Québe. In Guide des Bonnes Pratiques Afin de Favoriser l’acceptabilité Sociale des Projets/Guide to Good Practices in Order to Promote the Social Acceptability of Projects; Conseil Patronal de l’Environnement du Québec (CPEQ): Montréal, QC, Canada, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Westley, F.; Vredenburg, H. Interorganizational Collaboration and the Preservation of Global Biodiversity. Organ. Sci. 1997, 8, 381–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brewis, A.; Gartin, M.; Wutich, A.; Young, A. Global Convergence in Ethnotheories of Water and Disease. Glob Public Health 2013, 8, 13–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shindler, B.; Brunson, M. Social Acceptability in Forest and Range Management. Society and Natural Resources: A Summary of Knowledge; Modern Litho Press: Jefferson, MO, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Goldman, S. 190 Projects to Change the World. Dans G. I. Research (Dir.); Goldman Sachs: New York, NY, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Kostalova, J.; Tetrevova, L. Project Management and Its Tools in Practice in the Czech Republic. Procedia-Soc. Behav. Sci. 2014, 150, 678–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Stankey, G.H.; Shindler, B. Formation of Social Acceptability Judgments and Their Implications for Management of Rare and Little-Known Species. Conserv. Biol. 2006, 20, 28–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joyce, S.; Thomson, I. Earning a Social Licence to Operate: Social Acceptability and Resource Development in Latin America. CIM Bull. 2000, 93, 49–53. [Google Scholar]

- Slack, K. Corporate Social License and Community Consent. Policy Innov. 2008, 21. [Google Scholar]

- Caron-Malenfant, J.; Conraud, T. Guide Pratique de l’acceptabilité Sociale: Pistes de Réflexion et d’action; Éditions DPRM: Montréal, QC, Canada, 2009; ISBN 2981069411. [Google Scholar]

- Gendron, C. Penser l’acceptabilité Sociale: Au-Delà de l’intérêt, Les Valeurs. Commun. Rev. Commun. Soc. Publique 2014, 1, 117–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batellier, P. Revoir Les Processus de Décision Publique: De l’acceptation Sociale à l’acceptabilité Sociale; Gaïa Presse: Montreal, QC, Canada, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- CNS-C. des syndicats nationaux L’acceptabilité Sociale. In Service Des Relations Du Travail Module Recherche; CNS-C: Montreal, QC, Canada, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Wioland, L.; Debay, L.; Atain-Kouadio, J.-J. Acceptation Des Exosquelettes Par Les Opérateurs: Étude Exploratoire. Réf. Santé Trav. 2019, 157, 45–61. [Google Scholar]

- Boutilier, R.G.; Thomson, I. Modelling and Measuring the Social License to Operate: Fruits of a Dialogue between Theory and Practice. Soc. Licence 2011, 1, 1–10. [Google Scholar]

| Stakeholders | Actors Met | Tools for Data Collection | Sampling | Number of Respondents | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Men | Women | Total | ||||

| UNICEF Burkina | Sections WASH | Individual Interview Guide | Reasoned choice | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| NGO implementing partners | Association for Peace and Solidarity (APS), Plan International, AMUS, AEDD, WaterAid, WeltHungerHilfe (WHH) | Individual Interview Guide | Reasoned choice | 8 | 4 | 12 |

| Institutional actors | At the central level (the General Department of Sanitation (DGA) of the Ministry of Water and Sanitation) | Individual Interview Guide | Reasoned choice | 0 | 2 | 2 |

| At the decentralized level (water and sanitation department of the central-west region, Provincial Department of Water and Sanitation of Sissili of Ziro and Boulkiemdé) | Individual Interview Guide | Reasoned choice | 2 | 0 | 2 | |

| High commissioner of Sissili and Boulkiemdé | Individual Interview Guide | Reasoned choice | 2 | 0 | 2 | |

| Health district of Sissili, health district of Leo (Sissili), Sapouy (Ziro), Koudougou (Boulkiemdé), and Nanoro (Boulkiemdé) | Individual Interview Guide | Reasoned choice | 5 | 1 | 6 | |

| At the local level (municipalities) | Individual Interview Guide | Reasoned choice | 3 | 0 | 3 | |

| Public structures | Health facilities (health centers) | Individual Interview Guide | Reasoned choice | 3 | 1 | 4 |

| Community stakeholders | Traditional and religious leaders | Individual Interview Guide | Reasoned choice | 9 | 0 | 9 |

| Village sanitation committee (VSC or CAV/Q) | Individual Interview Guide | Reasoned choice | 10 | 4 | 14 | |

| Private operators (masons, shopkeepers) | Individual Interview Guide | Reasoned choice | 5 | 0 | 5 | |

| Households | Men and women | Household survey | Random selection | 292 | 198 | 490 |

| TOTAL | 340 | 210 | 550 | |||

| Category | Factors |

|---|---|

| Environmental factors (C1) | Low ecological footprint |

| Clear regulations | |

| Adoption of a sustainable development policy by the promoters | |

| Adequate information to the population on the real risks of the project | |

| Knowledge of environmental risk mitigation measures by the communities | |

| Added value of environmental outputs (reuse, industrial synergy, etc.) | |

| A project will be more attractive if the outputs have local outlets (reused waste/rejects, etc.) | |

| Social factors (C2) | Favorable historical context |

| Good reputation of the company involved in the project | |

| Early consultation and transparency (access to quality information) | |

| Non-opposition with the cultural practices and habits of the area | |

| Positive social spinoffs after the project | |

| Economic factors (C3) | Rigorous and independent evaluation of project benefits |

| Favorable community purchasing power | |

| Positive spinoffs that go beyond economic profitability for investors | |

| Economic profitability | |

| Favorable economic context | |

| Governance factors (C4) | Collaborative and participatory governance model involving the community in the different stages of decision-making and not the traditional governance model based on top-down planning, in which the territories only implement government orientations |

| Technological factors (C5) | Upstream technology information |

| Use of reliable and efficient technologies | |

| User-friendly operation, maintenance, and upkeep of reliable and efficient technologies | |

| Rigorous control of operations and inputs | |

| Territorial factors (C6) | Good knowledge of the territory in its multiple dimensions |

| Respect for the integrity of the territory: fauna, flora, biodiversity, infrastructures, real estate heritage, etc. | |

| Respect for local and indigenous communities and their ancestral and treaty rights | |

| Low impact on tourist, economic, industrial, and other activities. |

| Category | Factors | Score Factor | Score Category |

|---|---|---|---|

| Environmental factors (C1) | Factor 1 | n1 | Score C1 = |

| Factor 2 | n2 | ||

| . . | . . | ||

| Factor N | nN | ||

| Social factors (C2) | Factor 1 | n1 | Score C2 = |

| Factor 2 | n2 | ||

| . . | . . | ||

| Factor N | nN | ||

| Economic factors (C3) | Factor 1 | n1 | Score C3 = |

| Factor 2 | n2 | ||

| . . | . . | ||

| Factor N | nN | ||

| Governance factors (C4) | Factor 1 | n1 | Score C4 = |

| Factor 2 | n2 | ||

| . . | . . | ||

| Factor N | nN | ||

| Technological factors (C5) | Factor 1 | n1 | Score C5 = |

| Factor 2 | n2 | ||

| . . | . . | ||

| Factor N | nN | ||

| Territorial factors (C6) | Factor 1 | n1 | Score C6 = |

| Factor 2 | n2 | ||

| . . | . . | ||

| Factor N | nN |

| Category | Factors | Score Factor | Score Category |

|---|---|---|---|

| Environmental factors (C1) | Understanding the health and economic consequences of OD | 550 | 592 |

| Desire for a clean living environment and the reduction of nauseating odors | 42 | ||

| Social factors (C2) | Men’s desire to protect their wives’ privacy | 138 | 390 |

| Women’s understanding of the adverse effects of OD on their children’s health | 119 | ||

| Natural rivalry between villages located in the same geographical area | 80 | ||

| No or very few internal cohesion or chieftaincy problems | 46 | ||

| Social pressure from one group on another group or an individual | 7 | ||

| Socio-cultural beliefs | 0 | ||

| Governance factors (C4) | Commitment of natural leaders | 88 | 247 |

| Good communication of the message conveyed by the CLTS approach in the local language | 42 | ||

| Promises during CLTS triggers | 32 | ||

| Sharing of CLTS experiences and successes by natural leaders | 29 | ||

| Institutional triggering of CLTS | 18 | ||

| Experience of CLTS facilitators and animators | 18 | ||

| Presence of representatives of the ministries and authorities on the day of CLTS triggering and intervention of the high commissioner or the mayor for mediation | 12 | ||

| Uniqueness of the type of approach in a geographical area | 2 | ||

| Monopoly of implementation by an NGO/association in the geographical area | 2 | ||

| Good coordination between CLTS implementation actors | 2 | ||

| Entering the target community for initiation with a team that does not have a history of conflict with that community | 2 | ||

| Territorial factors (C6) | Popularity and reputation of ODF-certified villages | 179 | 189 |

| Same type of approach taken in surrounding communities | 10 | ||

| Economic factors (C3) | Projected increase in income and diversification of activities | 5 | 15 |

| Projected increase in demand for skills (for masons) | 5 | ||

| Projected increase in demand for latrine construction materials | 5 | ||

| Technological factors (C5) | 0 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kouassi, H.A.A.; Andrianisa, H.A.; Traoré, M.B.; Sossou, S.K.; Nguematio, R.M.; Djambou, M.D. Acceptance Factors for the Social Norms Promoted by the Community-Led Total Sanitation (CLTS) Approach in the Rural Areas: Case Study of the Central-Western Region of Burkina Faso. Sustainability 2023, 15, 11945. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151511945

Kouassi HAA, Andrianisa HA, Traoré MB, Sossou SK, Nguematio RM, Djambou MD. Acceptance Factors for the Social Norms Promoted by the Community-Led Total Sanitation (CLTS) Approach in the Rural Areas: Case Study of the Central-Western Region of Burkina Faso. Sustainability. 2023; 15(15):11945. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151511945

Chicago/Turabian StyleKouassi, Hemez Ange Aurélien, Harinaivo Anderson Andrianisa, Maïmouna Bologo Traoré, Seyram Kossi Sossou, Rikyelle Momo Nguematio, and Maeva Dominique Djambou. 2023. "Acceptance Factors for the Social Norms Promoted by the Community-Led Total Sanitation (CLTS) Approach in the Rural Areas: Case Study of the Central-Western Region of Burkina Faso" Sustainability 15, no. 15: 11945. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151511945

APA StyleKouassi, H. A. A., Andrianisa, H. A., Traoré, M. B., Sossou, S. K., Nguematio, R. M., & Djambou, M. D. (2023). Acceptance Factors for the Social Norms Promoted by the Community-Led Total Sanitation (CLTS) Approach in the Rural Areas: Case Study of the Central-Western Region of Burkina Faso. Sustainability, 15(15), 11945. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151511945