Strategic CSR: Framework for Sustainability through Management Systems Standards—Implementing and Disclosing Sustainable Development Goals and Results

Abstract

:1. Introduction

- RQ1:

- What are the main SDGs disclosed in institutional reports by Portuguese organizations with multiple certified MSs (QEOH&S&SR)?

- RQ2:

- What are the main SDRs disclosed in institutional reports by Portuguese organizations with multiple certified MSs (QEOH&S&SR)?

- RQ3:

- How is the disclosure of SDGs and SDRs in institutional reports correlated?

2. Literature Review

2.1. Communication on Sustainable Development

2.2. Sustainable Development Goals

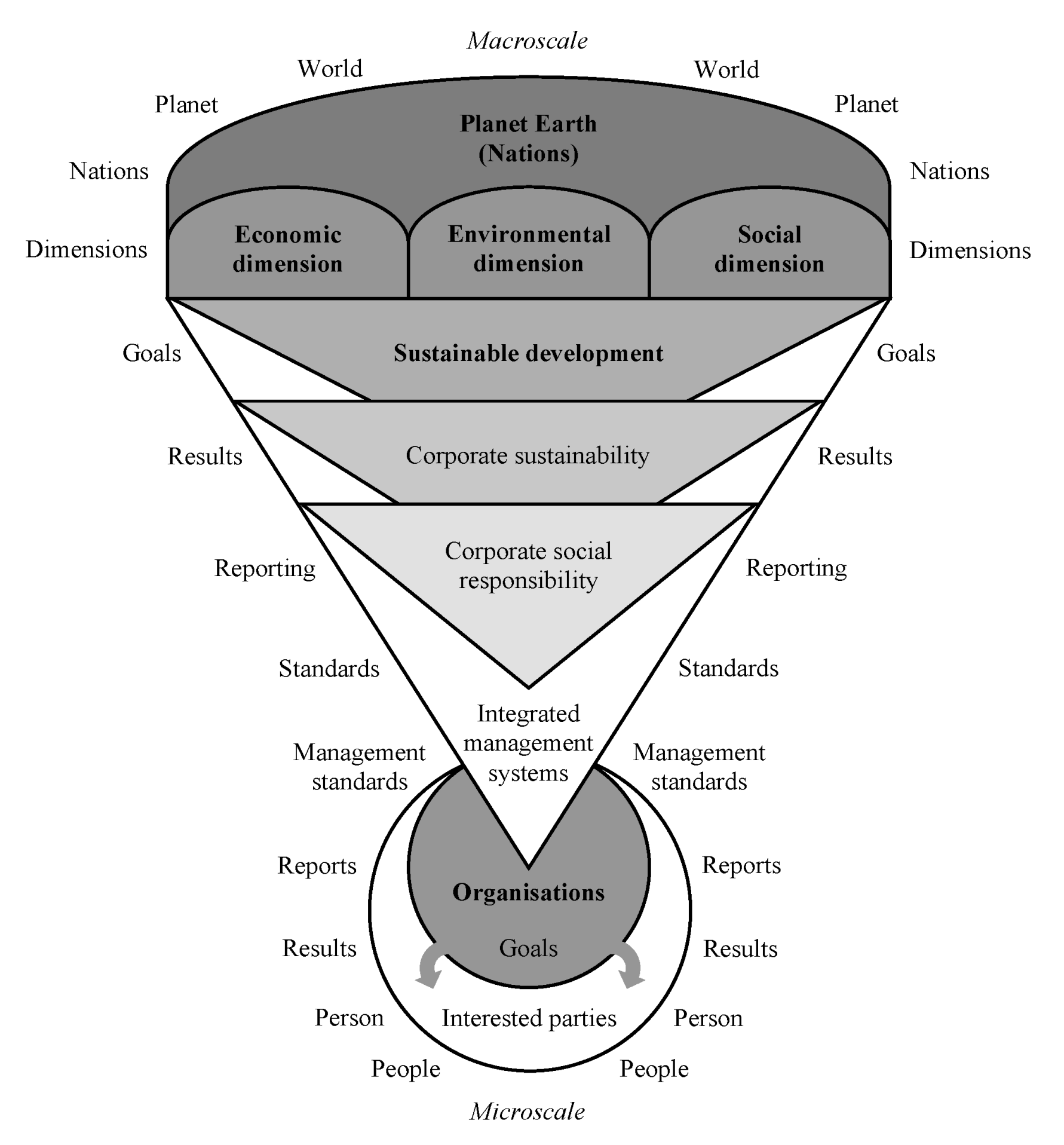

2.3. Sustainable Development through Management Systems: A Proposed Framework

2.4. Communication through Management Systems and Institutional Reports

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Research Sample

- Made an institutional website accessible on the internet on 31 July 2019 (i.e., the final date of the exploratory analysis).

- Disclosed at least one of their institutional reports on the website in the past four years (i.e., published from 2015 to 2018).

3.2. Research Method

3.3. Research Data

4. Results

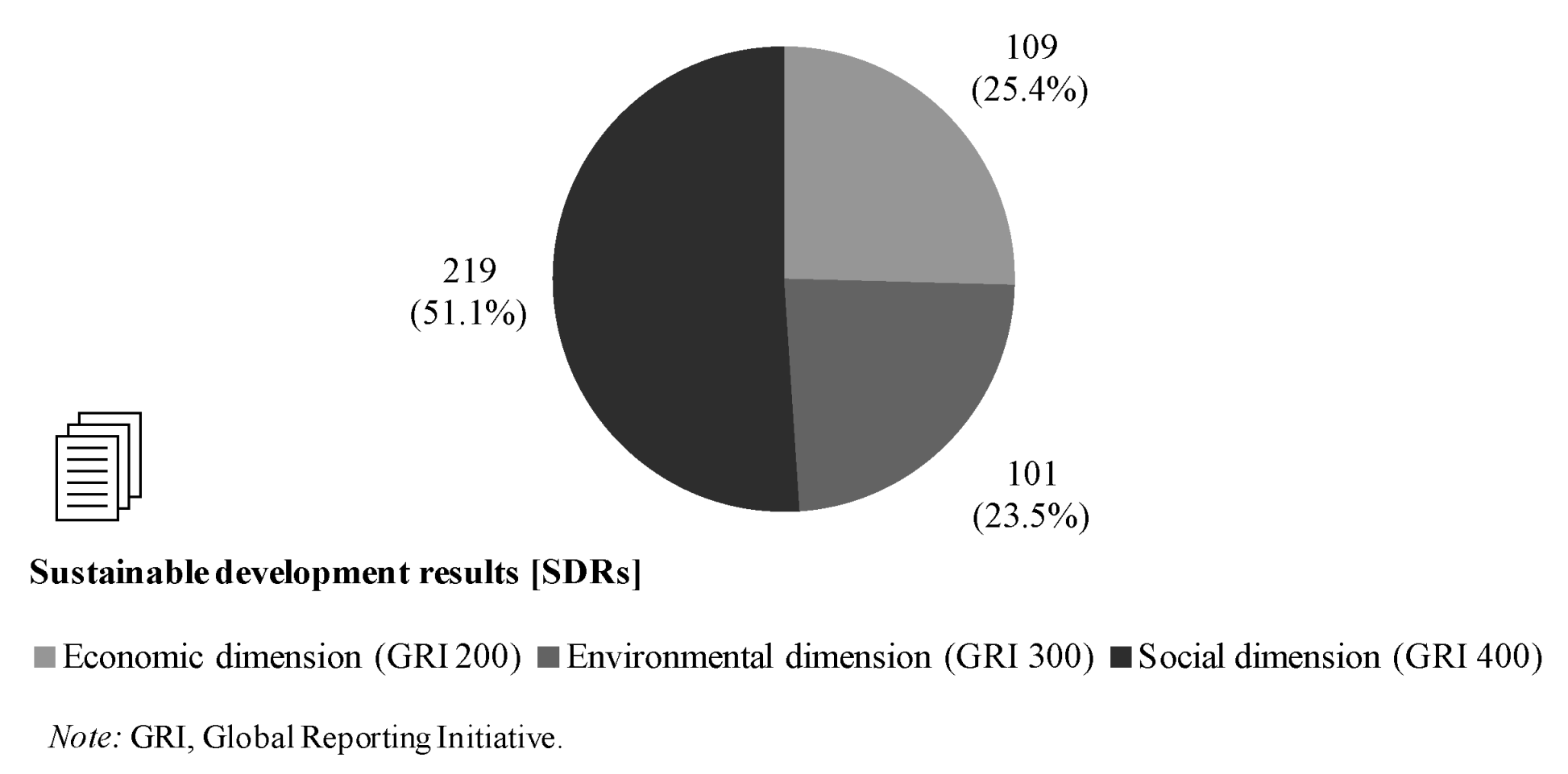

4.1. Descriptive Statistics Analysis

4.2. Bivariate Correlation Analysis

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Meadows, D.H.; Meadows, D.L.; Randers, J.; Behrens, W.W., III. The Limits to Growth: A Report for the Club of Rome’s Project on the Predicament of Mankind; Universe Books: Singapore, 1972. [Google Scholar]

- World Commission on Environment and Development. Our Common Future; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- World Commission on Environment and Development. The Report of the World Commission on Environment and Development: Our Common Future; UN General Assembly No. A/42/427; United Nations (UN): New York, NY, USA, 1987; Available online: http://www.un.org/ga/search/view_doc.asp?symbol=A/42/427&Lang=E (accessed on 1 January 2020).

- Cöster, M.; Dahlin, G.; Isaksson, R. Are they reporting the right thing and are they doing it right?—A measurement maturity grid for evaluation of sustainability reports. Sustainability 2020, 12, 10393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isaksson, R. Excellence for sustainability—Maintaining the license to operate. Total Qual. Manag. Bus. Excell. 2021, 32, 489–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bansal, P. Evolving sustainably: A longitudinal study of corporate sustainable development. Strateg. Manag. J. 2005, 26, 197–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lozano, R. Envisioning sustainability three-dimensionally. J. Clean. Prod. 2008, 16, 1838–1846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strezov, V.; Evans, A.; Evans, T.J. Assessment of the economic, social and environmental dimensions of the indicators for sustainable development. Sustain. Dev. 2017, 25, 242–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosati, F.; Faria LG, D. Addressing the SDGs in sustainability reports: The relationship with institutional factors. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 215, 1312–1326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steurer, R.; Langer, M.E.; Konrad, A.; Martinuzzi, A. Corporations, stakeholders and sustainable development I: A theoretical exploration of business–society relations. J. Bus. Ethics 2005, 61, 263–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, F.; Santos, G.; Gonçalves, J. The disclosure of information on sustainable development on the corporate website of the certified Portuguese organizations. Int. J. Qual. Res. 2018, 12, 253–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fonseca, L.; Silva, V.; Sá, J.C.; Lima, V.; Santos, G.; Silva, R. B Corp versus ISO 9001 and 14001 certifications: Aligned, or alternative paths, towards sustainable development? Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2022, 29, 496–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeman, R.E.; Phillips, R.; Sisodia, R. Tensions in stakeholder theory. Bus. Soc. 2020, 59, 213–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siltaloppi, J.; Rajala, R.; Hietala, H. Integrating CSR with business strategy: A tension management perspective. J. Bus. Ethics 2021, 174, 507–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strand, R.; Freeman, R.E.; Hockerts, K. Corporate Social Responsibility and Sustainability in Scandinavia: An Overview. J. Bus. Ethics 2015, 127, 1–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Welford, R.; Frost, S. Corporate Social Responsibility in Asian Supply Chains. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2006, 13, 166–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rhou, Y.; Singal, M.; Koh, Y. CSR and Financial Performance: The Role of CSR Awareness in the Restaurant Industry. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2016, 57, 30–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, F.; Santos, G.; Gonçalves, J. Critical analysis of information about integrated management systems and environmental policy on the Portuguese firms’ website, towards sustainable development. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2020, 27, 1069–1088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsalis, T.A.; Malamateniou, K.E.; Koulouriotis, D.; Nikolaou, I.E. New challenges for corporate sustainability reporting: United Nations’ 2030 Agenda for sustainable development and the sustainable development goals. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2020, 27, 1617–1629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeman, R.E. Strategic Management: A Stakeholder Approach; Pitman Publishing: London, UK, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Ikram, M.; Zhang, Q.; Sroufe, R.; Ferasso, M. Contribution of certification bodies and sustainability standards to sustainable development goals: An integrated grey systems approach. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2021, 28, 326–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Marrewijk, M. Concepts and definitions of CSR and corporate sustainability: Between agency and communion. J. Bus. Ethics 2003, 44, 95–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robert, K.W.; Parris, T.M.; Leiserowitz, A.A. What is sustainable development? Goals, indicators, values, and practice. Environ. Sci. Policy Sustain. Dev. 2005, 47, 8–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pojasek, R.B. Scoring sustainability results. Environ. Qual. Manag. 2003, 13, 91–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azapagic, A. Systems approach to corporate sustainability: A general management framework. Process. Saf. Environ. Prot. 2003, 81, 303–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Siew, R.Y.J. A review of corporate sustainability reporting tools (SRTs). J. Environ. Manag. 2015, 164, 180–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pizzi, S.; Del Baldo, M.; Caputo, F.; Venturelli, A. Voluntary disclosure of sustainable development goals in mandatory non-financial reports: The moderating role of cultural dimension. J. Int. Financ. Manag. Account. 2022, 33, 83–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- PricewaterhouseCoopers International. SDG Challenge 2019: Creating a Strategy for a Better World; PwC Report No. SDG Challenge 2019; 2019. Available online: https://www.pwc.com/gx/en/services/sustainability/sustainable-development-goals/sdg-challenge-2019.html (accessed on 1 January 2020).

- Manes-Rossi, F.; Nicolo’, G. Exploring sustainable development goals reporting practices: From symbolic to substantive approaches—Evidence from the energy sector. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2022, 29, 1799–1815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, S. Corporate contributions to the sustainable development goals: An empirical analysis informed by legitimacy theory. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 292, 125962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crane, A.; Ruebottom, T. Stakeholder theory and social identity: Rethinking stakeholder identification. J. Bus. Ethics 2011, 102 (Suppl. S1), 77–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barney, J. Firm resources and sustained competitive advantage. J. Manag. 1991, 17, 99–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barney, J.B. Resource-based theories of competitive advantage: A ten-year retrospective on the resource-based view. J. Manag. 2001, 27, 643–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DiMaggio, P.J.; Powell, W.W. The iron cage revisited: Institutional isomorphism and collective rationality in organizational fields. Am. Sociol. Rev. 1983, 48, 147–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Camilleri, M.A. Valuing stakeholder engagement and sustainability reporting. Corp. Reput. Rev. 2015, 18, 210–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camilleri, M.A. The market for socially responsible investing: A review of the developments. Soc. Responsib. J. 2021, 17, 412–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hummel, K.; Szekely, M. Disclosure on the sustainable development goals—Evidence from Europe. Account. Eur. 2022, 19, 152–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ionașcu, E.; Mironiuc, M.; Anghel, I.; Huian, M.C. The involvement of real estate companies in sustainable development—An analysis from the SDGs reporting perspective. Sustainability 2020, 12, 798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Filho, W.L.; Vidal, D.G.; Chen, C.; Petrova, M.; Dinis, M.A.P.; Yang, P.; Rogers, S.; Álvarez-Castañón, L.; Djekic, I.; Sharifi, A.; et al. An assessment of requirements in investments, new technologies and infrastructures to achieve the SDGs. Environ. Sci. Eur. 2022, 34, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, W.M.; Chin, M.W.C.; Ee, Y.S.; Fung, C.Y.; Giang, C.S.; Heng, K.S.; Kong, M.L.F.; Lim, A.S.S.; Lim, B.C.Y.; Lim, R.T.H.; et al. What is at stake in a war? A prospective evaluation of the Ukraine and Russia conflict for business and society. Glob. Bus. Organ. Excell. 2022, 41, 23–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lozano, R.; Barreiro-Gen, M. Organisations’ contributions to sustainability. An analysis of impacts on the Sustainable Development Goals. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Welford, R. (Ed.) Hijacking Environmentalism: Corporate Responses to Sustainable Development, 1st ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 1997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Büthe, T.; Mattli, W. The New Global Rulers: The Privatization of Regulation in the World Economy; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Nunhes, T.V.; Espuny, M.; Campos, T.L.R.; Santos, G.; Bernardo, M.; Oliveira, O.J. Guidelines to build the bridge between sustainability and integrated management systems: A way to increase stakeholder engagement toward sustainable development. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2022, 29, 1617–1635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rebelo, M.F.; Santos, G.; Silva, R. Integration of management systems: Towards a sustained success and development of organizations. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 127, 96–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Organization for Standardization; International Electrotechnical Commission. ISO/IEC Directives, Part 1: Consolidated ISO Supplement—Procedures for the Technical Work—Procedures Specific to ISO; ISO/IEC Standard No. ISO/IEC Directives, Part 1. 2021. Available online: https://www.iso.org/sites/directives/current/consolidated/index.xhtml (accessed on 1 January 2023).

- Blind, K.; Heß, P. Stakeholder perceptions of the role of standards for addressing the sustainable development goals. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2023, 37, 180–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- PAS 99:2012; Specification of Common Management System Requirements as a Framework for Integration. British Standards Institution: London, UK, 2012. Available online: https://shop.bsigroup.com/ProductDetail?pid=000000000030254209 (accessed on 1 January 2020).

- NP 4469:2019; Sistema de Gestão da Responsabilidade Social—Requisitos e Linhas de Orientação para a Sua utilização [Social Responsibility Management System—Requirements and Guidelines for Its Usage]. Instituto Português da Qualidade: Caparica, Portugal, 2019. Available online: https://lojanormas.ipq.pt/product/np-4469-2019/ (accessed on 1 January 2023).

- ISO 14001:2015; Environmental Management Systems—Requirements with Guidance for Use. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2015. Available online: https://www.iso.org/standard/60857.html (accessed on 1 January 2023).

- ISO 9001:2015; Quality Management Systems—Requirements. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2015. Available online: https://www.iso.org/standard/62085.html (accessed on 1 January 2023).

- ISO 45001:2018; Occupational Health and Safety Management Systems—Requirements with Guidance for Use. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2018. Available online: https://www.iso.org/standard/63787.html (accessed on 1 January 2023).

- ISO 9000:2015; Quality Management Systems—Fundamentals and Vocabulary. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2015. Available online: https://www.iso.org/standard/45481.html (accessed on 1 January 2023).

- BS OHSAS 18001:2007; Occupational Health and Safety Management Systems—Requirements. British Standards Institution: London, UK, 2007. Available online: https://shop.bsigroup.com/ProductDetail/?pid=000000000030148086 (accessed on 1 January 2023).

- ISO 26000:2010; Guidance on Social Responsibility. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2010. Available online: https://www.iso.org/standard/42546.html (accessed on 1 January 2023).

- Fonseca, L.M.; Domingues, J.P.; Machado, P.B.; Calderón, M. Management System Certification Benefits: Where Do We Stand? J. Ind. Eng. Manag. 2017, 10, 476–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ikram, M.; Zhang, Q.; Sroufe, R. Developing integrated management systems using an AHP-Fuzzy VIKOR approach. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2020, 29, 2265–2283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, G.; Mendes, F.; Barbosa, J. Certification and integration of management systems: The experience of Portuguese small and medium enterprises. J. Clean. Prod. 2011, 19, 1965–1974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Silva, C.; Magano, J.; Moskalenko, A.; Nogueira, T.; Dinis, M.; Pedrosa e Sousa, H.F. Sustainable management systems standards (SMSS): Structures, roles, and practices in corporate sustainability. Sustainability 2020, 12, 5892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernandez-Vivanco, A.; Domingues, P.; Sampaio, P.; Bernardo, M.; Cruz-Cázares, C. Do multiple certifications leverage firm performance? A dynamic approach. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2019, 218, 386–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ikram, M.; Zhang, Q.; Sroufe, R.; Ferasso, M. The social dimensions of corporate sustainability: An integrative framework including COVID-19 insights. Sustainability 2020, 12, 8747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freundlieb, M.; Teuteberg, F. Corporate social responsibility reporting—A transnational analysis of online corporate social responsibility reports by market-listed companies: Contents and their evolution. Int. J. Innov. Sustain. Dev. 2013, 7, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diaz-Sarachaga, J.M. Shortcomings in reporting contributions towards the sustainable development goals. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2021, 28, 1299–1312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erin, O.A.; Bamigboye, O.A. Evaluation and analysis of SDG reporting: Evidence from Africa. J. Account. Organ. Chang. 2022, 18, 369–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fonseca, L.; Carvalho, F. The reporting of SDGs by quality, environmental, and occupational health and safety-certified organizations. Sustainability 2019, 11, 5797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Izzo, M.F.; Ciaburri, M.; Tiscini, R. The challenge of sustainable development goal reporting: The first evidence from Italian listed companies. Sustainability 2020, 12, 3494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Guarini, E.; Mori, E.; Zuffada, E. Localizing the sustainable development goals: A managerial perspective. J. Public Budg. Account. Financ. Manag. 2022, 34, 583–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leal Filho, W.; Ulisses, A.; Alves, F.; Pace, P.; Mifsud, M.; Brandli, L.; Caeiro, S.S.; Disterheft, A. Reinvigorating the sustainable development research agenda: The role of the sustainable development goals (SDG). Int. J. Sustain. Dev. World Ecol. 2018, 25, 131–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- United Nations. Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development (UN General Assembly Resolution No. A/RES/70/1). 2015. Available online: https://undocs.org/A/RES/70/1 (accessed on 1 January 2020).

- Fonseca, L.M.; Domingues, J.P.; Dima, A.M. Mapping the sustainable development goals relationships. Sustainability 2020, 12, 3359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Heemskerk, B.; Pistorio, P.; Scicluna, M. Sustainable Development Reporting: Striking the Balance; World Business Council for Sustainable Development: Geneva, Switzerland, 2002; Available online: https://www.wbcsd.org/Programs/Redefining-Value/External-Disclosure/Reporting-matters/Resources/Sustainable-Development-Reporting-Striking-the-balance (accessed on 1 January 2020).

- Carvalho, F.; Domingues, P.; Sampaio, P. Communication of commitment towards sustainable development of certified Portuguese organisations: Quality, environment and occupational health and safety. Int. J. Qual. Reliab. Manag. 2019, 36, 458–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saber, M.; Weber, A. Sustainable grocery retailing: Myth or reality?—A content analysis. Bus. Soc. Rev. 2019, 124, 479–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chowdhury, E.H.; Rambaree, B.B.; Macassa, G. CSR reporting of stakeholders’ health: Proposal for a new perspective. Sustainability 2021, 13, 1133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Girella, L.; Zambon, S.; Rossi, P. Reporting on sustainable development: A comparison of three Italian small and medium-sized enterprises. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2019, 26, 981–996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GRI 2020; Consolidated Set of GRI Sustainability Reporting Standards 2020. Global Reporting Initiative: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2020. Available online: https://www.globalreporting.org/standards/gri-standards-download-center/ (accessed on 1 January 2022).

- SDG Compass. The Guide for Business Action on the SDGs. 2020. Available online: https://sdgcompass.org (accessed on 1 January 2022).

- Yin, C.; Zhao, W.; Fu, B.; Meadows, M.E.; Pereira, P. Key axes of global progress towards the Sustainable Development Goals. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 385, 135767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elkington, J. Cannibals with Forks: The Triple Bottom Line of 21st Century Business; Capstone Publishing Limited: Oxford, UK, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Elkington, J. Enter the triple bottom line. In The Triple Bottom Line: Does It All Add Up? Henriques, A., Richardson, J., Eds.; Earthscan: London, UK, 2004; pp. 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Pacheco JA, B.; Teijeiro-Álvarez, M.M.; García-Álvarez, M.T. Sustainable development in the economic, environmental, and social fields of Ecuadorian universities. Sustainability 2020, 12, 7384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Castka, P.; Searcy, C. ISO standards: A platform for achieving sustainable development goal 2. Sustainability 2020, 12, 9332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rashed, A.H.; Rashdan, S.A.; Ali-Mohamed, A.Y. Towards effective environmental sustainability reporting in the large industrial sector of Bahrain. Sustainability 2022, 14, 219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calabrese, A.; Costa, R.; Gastaldi, M.; Ghiron, N.L.; Montalvan, R.A.V. Implications for sustainable development goals: A framework to assess company disclosure in sustainability reporting. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 319, 128624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elalfy, A.; Weber, O.; Geobey, S. The sustainable development goals (SDGs): A rising tide lifts all boats? Global reporting implications in a post SDGs world. J. Appl. Account. Res. 2021, 22, 557–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivic, A.; Saviolidis, N.M.; Johannsdottir, L. Drivers of sustainability practices and contributions to sustainable development evident in sustainability reports of European mining companies. Discov. Sustain. 2021, 2, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siva, V.; Gremyr, I.; Bergquist, B.; Garvare, R.; Zobel, T.; Isaksson, R. The support of quality management to sustainable development: A literature review. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 138, 148–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Alsawafi, A.; Lemke, F.; Yang, Y. The impacts of internal quality management relations on the triple bottom line: A dynamic capability perspective. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2021, 232, 107927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chavez, R.; Yu, W.; Jajja MS, S.; Lecuna, A.; Fynes, B. Can entrepreneurial orientation improve sustainable development through leveraging internal lean practices? Bus. Strategy Environ. 2020, 29, 2211–2225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarí, J.J.; Molina-Azorín, J.F.; López-Gamero, M.D.; Pereira-Moliner, J. The association between environmental sustainable development and internalization of a quality standard. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2021, 30, 2587–2599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camilleri, M.A. Theoretical insights on integrated reporting: The inclusion of non-financial capitals in corporate disclosures. Corp. Commun. Int. J. 2018, 23, 567–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fonseca, L.M.C.M. ISO 14001:2015: An improved tool for sustainability. J. Ind. Eng. Manag. 2015, 8, 37–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Camilleri, M.A. The rationale for ISO 14001 certification: A systematic review and a cost–benefit analysis. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2022, 29, 1067–1083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Opoku-Mensah, E.; Chun, W.; Tuffour, P.; Chen, W.; Agyapong, R.A. Leveraging on structural change and ISO 14001 certification to mitigate ecological footprint in Shanghai cooperation organization nations. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 414, 137542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q. Sustainable development of occupational health and safety management system—Active upgrading of corporate safety culture. Int. J. Archit. Sci. 2004, 5, 108–113. Available online: http://www.bse.polyu.edu.hk/researchCentre/Fire_Engineering/summary_of_output/journal/IJAS/V5/p.108-113.pdf (accessed on 1 January 2020).

- Jilcha, K.; Kitaw, D. Industrial occupational safety and health innovation for sustainable development. Eng. Sci. Technol. Int. J. 2017, 20, 372–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Marhavilas, P.; Koulouriotis, D.; Nikolaou, I.; Tsotoulidou, S. International occupational health and safety management-systems standards as a frame for the sustainability: Mapping the territory. Sustainability 2018, 10, 3663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- SA 8000:2014; Social Accountability 8000. Social Accountability International: New York, NY, USA, 2014. Available online: https://sa-intl.org/resources/sa8000-standard/ (accessed on 1 January 2020).

- Murmura, F.; Bravi, L. Developing a corporate social responsibility strategy in India using the SA 8000 standard. Sustainability 2020, 12, 3481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Santos, G.; Murmura, F.; Bravi, L. SA 8000 as a tool for a sustainable development strategy. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2018, 25, 95–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jonkutė, G.; Staniškis, J.K.; Dukauskaitė, D. Social responsibility as a tool to achieve sustainable development in SMEs. Environ. Res. Eng. Manag. 2011, 57, 67–81. Available online: https://erem.ktu.lt/index.php/erem/article/view/465 (accessed on 1 January 2020).

- Castka, P.; Bamber, C.J.; Bamber, D.J.; Sharp, J.M. Integrating corporate social responsibility (CSR) into ISO management systems—In search of a feasible CSR management system framework. TQM Mag. 2004, 16, 216–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oskarsson, K.; Von Malmborg, F. Integrated management systems as a corporate response to sustainable development. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2005, 12, 121–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nadae, J.; Carvalho, M.M.; Vieira, D.R. Integrated management systems as a driver of sustainability performance: Exploring evidence from multiple-case studies. Int. J. Qual. Reliab. Manag. 2021, 38, 800–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbosa, A.S.; Silva, L.B.; Souza, V.F.; Morioka, S.N. Integrated management systems: Their organizational impacts. Total Qual. Manag. Bus. Excell. 2022, 33, 794–817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, F.J.F. A Comunicação de Resultados Sobre Desenvolvimento Sustentável nas Organizações Portuguesas Certificadas em Qualidade, Ambiente e Segurança [The Communication of Results on Sustainable Development in the Certified Portuguese organisations in Quality, Environment, and Safety]. Master’s Thesis, Instituto Superior de Engenharia do Porto—Instituto Politécnico do Porto, Repositório Científico do Instituto Politécnico do Porto, Porto, Portugal, 2019. Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/10400.22/14980 (accessed on 1 January 2020).

- Derqui, B. Towards sustainable development: Evolution of corporate sustainability in multinational firms. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2020, 27, 2712–2723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerged, A.M.; Cowton, C.J.; Beddewela, E.S. Towards sustainable development in the Arab Middle East and North Africa region: A longitudinal analysis of environmental disclosure in corporate annual reports. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2018, 27, 572–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Iorio, S.; Zampone, G.; Piccolo, A. Determinant factors of SDG disclosure in the university context. Adm. Sci. 2022, 12, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunawan, J.; Permatasari, P.; Tilt, C. Sustainable development goal disclosures: Do they support responsible consumption and production? J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 246, 118989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbott, W.F.; Monsen, R.J. On the measurement of corporate social responsibility: Self-reported disclosures as a method of measuring corporate social involvement. Acad. Manag. J. 1979, 22, 501–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schober, P.; Boer, C.; Schwarte, L.A. Correlation coefficients: Appropriate use and interpretation. Anesth. Analg. 2018, 126, 1763–1768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ching, H.Y.; Gerab, F. Sustainability reports in Brazil through the lens of signaling, legitimacy and stakeholder theories. Soc. Responsib. J. 2017, 13, 95–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krippendorff, K. Content Analysis: An Introduction to Its Methodology, 4th ed.; Sage Publications: New York, NY, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Heras-Saizarbitoria, I.; Urbieta, L.; Boiral, O. Organizations’ engagement with sustainable development goals: From cherry-picking to SDG-washing? Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2022, 29, 316–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bastas, A.; Liyanage, K. ISO 9001 and supply chain integration principles based sustainable development: A delphi study. Sustainability 2018, 10, 4569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lambrechts, W.; Son-Turan, S.; Reis, L.; Semeijn, J. Lean, green and clean? Sustainability reporting in the logistics sector. Logistics 2019, 3, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kolsi, M.C.; Ananzeh, M.; Awawdeh, A. Compliance with the global reporting initiative standards in Jordan: Case study of hikma pharmaceuticals. Int. J. Sustain. Eng. 2021, 14, 1572–1586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fonseca, L. The EFQM 2020 model. A theoretical and critical review. Total Qual. Manag. Bus. Excell. 2022, 33, 1011–1038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Organization for Standardization. Contributing to the UN Sustainable Development Goals with ISO Standards. 2018. Available online: https://www.iso.org/publication/PUB100429.html (accessed on 1 January 2020).

- United Nations Economic and Social Council—ECOSOC. Progress towards the Sustainable Development Goals. Report of the Secretary-General; No 9780191577468; United Nations Economic and Social Council—ECOSOC: New York, NY, USA, 2022.

- Filho, W.L.; Trevisan, L.V.; Rampasso, I.S.; Anholon, R.; Dinis, M.A.P.; Brandli, L.L.; Sierra, J.; Salvia, A.L.; Pretorius, R.; Nicolau, M.; et al. When the alarm bells ring: Why the UN sustainable development goals may not be achieved by 2030. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 407, 137108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) | ISO 9001 (2015) | ISO 14001 (2015) | ISO 45001 (2018) | ISO 26000 (2010) | SA 8000 (2014) | NP 4469 (2019) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SDG 01: No poverty | ● | ● | ● | ● | ||

| SDG 02: Zero hunger | ● | ● | ● | |||

| SDG 03: Good health and well-being | ● | ● | ● | ● | ||

| SDG 04: Quality education | ● | ● | ● | |||

| SDG 05: Gender equality | ● | ● | ● | ● | ||

| SDG 06: Clean water and sanitation | ● | ● | ● | |||

| SDG 07: Affordable and clean energy | ● | ● | ● | |||

| SDG 08: Decent work and economic growth | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | |

| SDG 09: Industry, innovation, and infrastructure | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | |

| SDG 10: Reduced inequalities | ● | ● | ● | ● | ||

| SDG 11: Sustainable cities and communities | ● | ● | ● | |||

| SDG 12: Responsible consumption and production | ● | ● | ● | ● | ||

| SDG 13: Climate action | ● | ● | ● | |||

| SDG 14: Life below water | ● | ● | ● | ● | ||

| SDG 15: Life on land | ● | ● | ● | |||

| SDG 16: Peace, justice, and strong institutions | ● | ● | ● | |||

| SDG 17: Partnerships for the goals | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ● |

| Discipline | Definition of the Term or Concept | Reference(s) |

|---|---|---|

| Quality | Degree to which a set of inherent characteristics of an object fulfils requirements. | ISO [53] |

| Environment | Surroundings in which an organization operates, including air, water, land, natural resources, flora, fauna, humans, and their interrelationships. | ISO [50] |

| Occupational health and safety (OH&S) | Conditions and factors that affect, or could affect, the health and safety of employees or other workers (including temporary workers and contractor personnel), visitors, or any other person in the workplace. | BSI [54] |

| Social responsibility | Responsibility of an organization for the impacts of its decisions and activities on society and the environment, through transparent and ethical behavior that contributes to sustainable development, including health and the welfare of society; considers the expectations of stakeholders; is in compliance with applicable law and consistent with international norms of behavior; and is integrated throughout the organization and practiced in its relationships. | IPQ [49] and ISO [55] |

| Dimension | Potential Issues | Main Standard(s) |

|---|---|---|

| Economic | Economic performance and development Technology and innovation Value and supply chain Employment Business Poverty Income Others | ISO 9001:2015 Quality management systems—Requirements |

| Environmental | Protection of biodiversity and natural habitats Pollution of land, water, or air Natural resource use Climate change Energy use Others | ISO 14001:2015 Environmental management systems—Requirements with guidance for use |

| Social | Education, training, and literacy Community involvement Health and safety Labor relations Quality of life Social equity Culture Others | ISO 45001:2018 Occupational health and safety management systems—Requirements with guidance for use ISO 26000:2010 Guidance on social responsibility SA 8000:2014 Social accountability NP 4469:2019 Social responsibility management system—Requirements and guidelines for its usage |

| Scope | Referential | Communication Requirements | Internal | External |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Quality management systems | ISO 9001:2015 | 5.2.2 Communicating the quality policy 7.4 Communication 8.2.1 Customer communication 8.4.3 Information for external providers | ● | |

| ● | ● | |||

| ● | ● | |||

| ● | ||||

| Environmental management systems | ISO 14001:2015 | 7.4 Communication 7.4.1 General 7.4.2 Internal communication 7.4.3 External communication | ● | ● |

| ● | ● | |||

| ● | ||||

| ● | ||||

| Occupational health and safety management systems | ISO 45001:2018 | 7.4 Communication 7.4.1 General 7.4.2 Internal communication 7.4.3 External communication | ● | ● |

| ● | ● | |||

| ● | ||||

| ● | ||||

| Social responsibility management systems | ISO 26000:2010 | 7.5 Communication on social responsibility 7.5.1 The role of communication in social responsibility 7.5.2 Characteristics of information relating to social responsibility 7.5.3 Types of communication on social responsibility 7.5.4 Stakeholder dialogue on communication about social responsibility | ● | ● |

| ● | ● | |||

| ● | ● | |||

| ● | ● | |||

| ● | ● | |||

| SA 8000:2014 | 9.5 Internal involvement and communication | ● | ||

| NP 4469:2019 | 7.4 Communication 7.4.1 General 7.4.2 Internal communication 7.4.3 External communication | ● | ● | |

| ● | ● | |||

| ● | ||||

| ● | ||||

| Integrated management systems | PAS 99:2012 | 7.4 Communication | ● | ● |

| Certified Management Systems (Standard) | n | % |

|---|---|---|

| QMS (ISO 9001) | 34 | 100 |

| EMS (ISO 14001) | 34 | 100 |

| OH&SMS (BS OHSAS 18001) | 34 | 100 |

| SRMS (SA 8000) | 23 | 67.6 |

| SRMS (NP 4469) | 11 | 32.4 |

| Correlation Coefficient Value | Correlation Level Interpretation |

|---|---|

| 0.00–0.10 | Negligible correlation |

| 0.10–0.39 | Weak correlation |

| 0.40–0.69 | Moderate correlation |

| 0.70–0.89 | Strong correlation |

| 0.90–1.00 | Very strong correlation |

| Institutional Reports | n | % |

|---|---|---|

| Sustainability report | 22 | 64.7 |

| Social responsibility report | 4 | 11.8 |

| Environmental report | 4 | 11.8 |

| Occupational health and safety report | 0 | 0.0 |

| Management report | 6 | 17.6 |

| Accounts report | 23 | 67.6 |

| Accounts and management report | 1 | 2.9 |

| Financial report | 7 | 20.6 |

| Corporate governance report | 10 | 29.4 |

| Integrated report | 0 | 0.0 |

| Categories of Analysis | Subcategories of Analysis | n | % |

|---|---|---|---|

| Social | SDG 01: No poverty | 6 | 17.6 |

| Social | SDG 02: Zero hunger | 7 | 20.6 |

| Social | SDG 03: Good health and well-being | 8 | 23.5 |

| Social | SDG 04: Quality education | 8 | 23.5 |

| Economic and social | SDG 05: Gender equality | 15 | 44.1 |

| Environmental and social | SDG 06: Clean water and sanitation | 15 | 44.1 |

| Economic and environmental | SDG 07: Affordable and clean energy | 6 | 17.6 |

| Economic and social | SDG 08: Decent work and economic growth | 9 | 26.5 |

| Economic | SDG 09: Industry, innovation, and infrastructure | 16 | 47.1 |

| Economic and social | SDG 10: Reduced inequalities | 14 | 41.2 |

| Environmental and social | SDG 11: Sustainable cities and communities | 7 | 20.6 |

| Economic and social | SDG 12: Responsible consumption and production | 16 | 47.1 |

| Environmental | SDG 13: Climate action | 15 | 44.1 |

| Environmental | SDG 14: Life below water | 15 | 44.1 |

| Environmental | SDG 15: Life on land | 17 | 50.0 |

| Social | SDG 16: Peace, justice, and strong institutions | 5 | 14.7 |

| Economic, environmental, and social | SDG 17: Partnerships for the goals | 16 | 47.1 |

| j | Certification Body | Economic Activity | Business Sector | District | SDGsDI | SDRsDI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 01 | APCER | TAs | Public | Lisbon | 0.529 | 0.222 |

| 02 | APCER | TAs | Public | Lisbon | 0.529 | 0.222 |

| 03 | APCER | OSAs | Public | Lisbon | 1.000 | 0.750 |

| 04 | APCER | TAs | Public | Lisbon | 0.529 | 0.361 |

| 05 | APCER | WCTS | Public | Setúbal | 0.529 | 0.500 |

| 06 | APCER | WCTS | Public | Faro | 0.529 | 0.528 |

| 07 | APCER | WCTS | Public | Coimbra | 0.529 | 0.500 |

| 08 | SGS ICS | WCTS | Public | Porto | 0.529 | 0.500 |

| 09 | SGS ICS | WCTS | Public | Vila Real | 0.529 | 0.528 |

| 10 | APCER | WRT | Private | Porto | 0.000 | 0.028 |

| 11 | APCER | E | Public | Lisbon | 0.000 | 0.694 |

| 12 | SGS ICS | C | Private | Lisbon | 0.000 | 0.111 |

| 13 | SGS ICS | WCTS | Public | Braga | 0.353 | 0.806 |

| 14 | BVC | AFSA | Private | Lisbon | 0.471 | 0.778 |

| 15 | APCER | SWM | Public | Faro | 0.000 | 0.278 |

| 16 | APCER | AFSA | Private | Lisbon | 0.000 | 0.222 |

| 17 | EIC | OSAs | Private | Lisbon | 0.000 | 0.000 |

| 18 | BVC | C | Private | Lisbon | 0.000 | 0.056 |

| 19 | APCER | AFSA | Private | Lisbon | 0.000 | 0.222 |

| 20 | APCER | MRPP | Private | Castelo Branco | 0.000 | 0.056 |

| 21 | APCER | SWM | Public | Porto | 0.588 | 0.528 |

| 22 | BVC | MFPBTP | Private | Portalegre | 0.588 | 0.306 |

| 23 | BVC | C | Private | Lisbon | 0.000 | 0.000 |

| 24 | SGS ICS | MNMMP | Private | Aveiro | 0.000 | 0.056 |

| 25 | APCER | EPD | Private | Lisbon | 1.000 | 0.611 |

| 26 | APCER | OSAs | Private | Lisbon | 1.000 | 0.750 |

| 27 | APCER | TS | Private | Lisbon | 1.000 | 0.611 |

| 28 | SGS ICS | OSAs | Private | Lisbon | 0.176 | 0.167 |

| 29 | APCER | WCTS | Public | Setúbal | 0.000 | 0.278 |

| 30 | SGS ICS | SWM | Public | Porto | 0.529 | 0.472 |

| 31 | BVC | C | Private | Lisbon | 0.529 | 0.472 |

| 32 | APCER | TS | Private | Lisbon | 0.000 | 0.000 |

| 33 | SGS ICS | SWM | Private | Portalegre | 0.000 | 0.250 |

| 34 | EIC | WRT | Private | Setúbal | 0.000 | 0.056 |

| Variable | N | Minimum | Maximum | Sum | Mean | SD | Variance |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SDGsDI | 34 | 0.000 | 1.000 | 11.471 | 0.337 | 0.348 | 0.121 |

| SDRsDI | 34 | 0.000 | 0.806 | 11.917 | 0.350 | 0.256 | 0.065 |

| Correlation between SDGsDI and SDRsDI | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Correlation | Statistical Test | N | Correlation Coefficient | p-Value (Two-Tailed) |

| Pearson’s “r” (r) | Parametric | 34 | 0.733 | 0.000 ** |

| Spearman’s “rho” (ρ) | Nonparametric | 34 | 0.697 | 0.000 ** |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Fonseca, L.; Carvalho, F.; Santos, G. Strategic CSR: Framework for Sustainability through Management Systems Standards—Implementing and Disclosing Sustainable Development Goals and Results. Sustainability 2023, 15, 11904. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151511904

Fonseca L, Carvalho F, Santos G. Strategic CSR: Framework for Sustainability through Management Systems Standards—Implementing and Disclosing Sustainable Development Goals and Results. Sustainability. 2023; 15(15):11904. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151511904

Chicago/Turabian StyleFonseca, Luis, Filipe Carvalho, and Gilberto Santos. 2023. "Strategic CSR: Framework for Sustainability through Management Systems Standards—Implementing and Disclosing Sustainable Development Goals and Results" Sustainability 15, no. 15: 11904. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151511904

APA StyleFonseca, L., Carvalho, F., & Santos, G. (2023). Strategic CSR: Framework for Sustainability through Management Systems Standards—Implementing and Disclosing Sustainable Development Goals and Results. Sustainability, 15(15), 11904. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151511904