Export Potential Analysis of Vietnamese Bottled Coconut Water by Incorporating Criteria Weights of MCDM into the Gravity of Trade Model

Abstract

1. Introduction

- RQ1: What are the marketing, industry, profitability, and target market-related factors identifying the export potential success of Vietnamese bottled coconut water?

- RQ2: Which factors are ranked top priority vs. least priority for small- and large-scale bottled coconut water manufacturers?

- RQ3: Which target market has a higher export potential success for Vietnamese bottled coconut water manufacturers?

2. Literature Review

2.1. Case Outline: Export Readiness of Vietnamese Bottled Coconut Water

2.2. Industrial Assets and Investments

2.3. Marketing and Sales Resources

2.4. Potential Profitability

2.5. Foothold in Target Market

3. Method

3.1. Data Collection

- (i)

- Secondary data: a literature review to identify important criteria to study export performance;

- (ii)

- Primary data: in-depth interviews with the experts to verify and amend the list of criteria prepared initially in step (i).

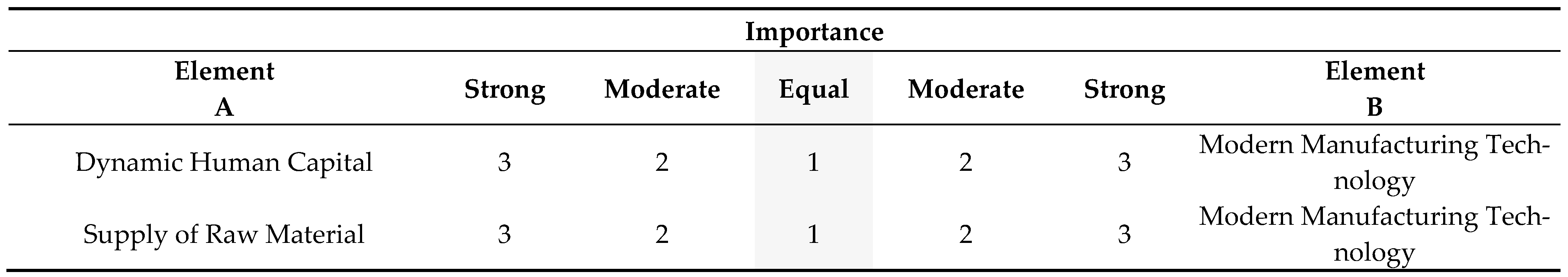

3.2. Pairwise Comparison Instrument

- ▪ Intensity 1 (equally): two elements contribute equally to the goal;

- ▪ Intensity 2 (moderately): experience and judgment slightly favor one activity over another;

- ▪ Intensity 3 (strongly): experience and judgment strongly favor one activity over another.

- (1)

- Industrial assets and investments (INDUS);

- (2)

- Marketing and sales (MRKT);

- (3)

- Potential profitability (PP);

- (4)

- Foothold in the target market (TM).

3.3. The AHP Method

- Define the decision problem and goal. The goal is to rank the criteria contributing to the export readiness of bottled coconut water manufactured in Vietnam.

- Identify and structure the decision criteria and alternatives. This method involves the identification and organization of (a) decision objectives, (b) criteria, (c) constraints, and alternatives into a hierarchical structure. The hierarchical structure starts with the goal of the study on top, followed by the levels of the set of criteria and alternatives, which form a decision matrix for analysis.

- Judge the relative value of the alternatives on each decision criterion. In this study, we capture the experts’ judgments through a pairwise comparison instrument.

- Judge or estimate the relative importance of the decision criteria. In this study, we use a criterion ranking method to compute the weights of the criteria based on the judgments captured in step 3.

- Group aggregation of judgments. The two traditionally accepted aggregation procedures in the AHP context are (i) the aggregation of individual judgments (AIJ) and (ii) the aggregation of individual priorities (AIP). Applying the proper aggregation method depends on whether the group of experts belongs to a homogeneous cluster acting like one single entity or operating in a context characterized by a conflict of interests; in such a case, the group members are individually acting with their own value systems, and a consensus may be reached using the AIP aggregation method [84].

- 6.

- Inconsistency analysis of judgments. AHP calculates a consistency ratio (CR) by comparing the consistency index (CI) of the matrix in question (the one with our judgments) versus the consistency index of a random-like matrix (RI). A random matrix is one where the judgments have been entered randomly, and therefore it is expected to be highly inconsistent. Table 3 shows Saaty’s RI per matrix size ranging from 1–10. The consistency ratio is then defined as CR = CI/RI. Saaty and Vargas [85] have shown that a consistency ratio (CR) of 0.01 or less is acceptable to continue the AHP analysis.

- 7.

- Calculation of the weights of the criteria and priorities of the alternatives.

- (i)

- Process the pairwise comparisons in a matrix and follow the steps in Saaty and Vargas [82] to transform the experts’ judgments into subjective weights for each criterion. These weights will be fed into the criteria ranking method to determine the relative importance of group criteria;

- (ii)

- Rank the alternatives of the decision matrix for further analysis and insights.

3.4. The M-CRITIC-RP Method for Group Criteria Ranking

3.5. The Gravity Model of Trade

4. Data and Empirical Results

- Even though the element “high purchasing power in popular export destinations” is commonly discussed by Vietnamese newspapers, the three experts believe that with high freight costs, distribution, and storage costs, the profit margins are not significantly affected. Thus, this element was dropped upon their request;

- Prior to the in-depth interviews, “strict requirements of quality standards imposed from importing countries” was listed as one of the most common challenges in exporting Vietnamese agricultural products in general. However, with the deployment of automation and advanced manufacturing technologies, the quality standards are now met; accordingly, this element was also eliminated;

- The element “complicated exporting procedure” was also eliminated. Recently, the Vietnamese government has been supporting the agricultural sector and simplifying procedures. According to the participants, the paperwork necessary for export activities can be delegated to an agency (third party) and could be completed within only one day. The participants also mentioned that Free-on-board (FOB) port policies are also followed in Vietnam;

- The three participants asked that “lack of government support” be dropped from the list of criteria, indicating that most of the challenges they face are due to their own weaknesses, and they do not see the government being responsible for it.

- (i)

- Industrial Assets and Investments (INDUS), which is defined by four criteria;

- (ii)

- Marketing and Sales (MRKT), which is defined by four criteria;

- (iii)

- Potential Profitability (PP), which is defined by four criteria;

- (iv)

- Foothold in Target Market (TM), which is defined by three criteria.

- ▪ The informants shared concerns about the role of unpredictable environmental changes affecting the supply of raw materials;

- ▪ From 2014 onwards, Vietnamese coconut water manufacturers started importing advanced technologies, mainly from Europe, for coconut water processing to improve production time, quality, and flavor mix. The technological advances in manufacturing also helped obtain organic certification from Europe and the United States;

- ▪ According to the informants, in Vietnam, there is a lack of capital investment from cultivation to processing. For example, farmers lack the capital to renew and improve existing coconut plantations. Processing businesses do not have enough money to expand the production scale or invest in new technology and machinery. The provincial budget is not enough to invest in thorough development to increase competitive advantages for the coconut industry;

- ▪ The three experts believe that with high freight costs, distribution, and storage costs, the profit margins are not significantly affected by export activities; it is the ability to sell more that makes global expansion attractive;

- ▪ According to the experts, it is tough for Vietnam’s coconut water manufacturers to own and expand their ownership of coconut water plantations to compete with foreign bulk merchants on price. Chinese merchants’ influence and a well-established network with highly fragmented farmers in Vietnam make their bargaining power higher than that of local buyers; this led to higher production costs affecting profitability;

- ▪ According to the informants, the paperwork necessary for exporting activities can be delegated to an agency (third party) and completed within only one day. The participants also mentioned that Free-on-board (FOB) port policies also facilitate transactions;

- ▪ The informants shared that they rely heavily on attending global food expos to expand their foreign distribution network. Still, they recognize it as not enough, and they lack the knowledge and expertise to gain access to distribution channels in foreign markets;

- ▪ Although many firms cite financial constraints as an essential impediment to their growth, we could not explore financial factors in more depth because the informants were not comfortable disclosing information on their financial stance or discussing financial solvency.

4.1. Processing Pairwise Comparisons

4.2. Normalization and Group Criteria Relative Weights: M-CRITIC-RP

4.3. Intra- and Inter-Criteria Rankings: AHP

- (1)

- Supply chain network (INDUS 1) in the INDUS group criteria;

- (2)

- Brand awareness (MRKT 2) in the MRKT group criteria;

- (3)

- Growing demand in the target market (PP 1) in the PP group criteria;

- (4)

- Distribution channels in the target market (TM 1) in the TM group criteria.

- (1)

- Distribution channels in the target market (TM 1);

- (2)

- Supply chain network (INDUS 1);

- (3)

- Brand awareness (MRKT 2);

- (4)

- Reliable sources of information on target markets (TM 2);

- (5)

- Reliable sources of information on target markets (TM 3).

- (1)

- Distribution channels in the target market (TM 1);

- (2)

- Brand awareness (MRKT 2);

- (3)

- Reliable sources of information on target markets (TM 3);

- (4)

- Supply chain network (INDUS 1);

- (5)

- Growing demand in target markets (PP1).

- (1)

- Trade agreements reducing taxes (PP 3), ranked 15th;

- (2)

- The fluctuating price of raw materials (PP 2), ranked 14th;

- (3)

- Modern manufacturing technology (INDUS 3), ranked 13th.

4.4. Target Market Potential: Gravity Trade Model with MCDM

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Debnath, B.; Shakur, M.S.; Bari, A.M.; Karmaker, C.L. A Bayesian Best–Worst approach for assessing the critical success factors in sustainable lean manufacturing. Decis. Anal. J. 2023, 6, 100157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aschemann-Witzel, J.; Bizzo, H.R.; Doria Chaves, A.C.S.; Faria-Machado, A.F.; Gomes Soares, A.; de Oliveira Fonseca, M.J.; Kidmose, U.; Rosenthal, A. Sustainable use of tropical fruits? Challenges and opportunities of applying the waste-to-value concept to international value chains. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2023, 63, 1339–1351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rethinam, P.; Krishnakumar, V. Tender coconut varieties. In Coconut Water: A Promising Natural Health Drink-Distribution, Processing and Nutritional Benefits; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 37–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rethinam, P.; Krishnakumar, V. Value addition in coconut water. In Coconut Water: A Promising Natural Health Drink-Distribution, Processing and Nutritional Benefits; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 287–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groth, A.; Goldschein, E. The Amazing Story of How Coconut Water Took Over the Beverage Industry. Business Insider. 2011. Business Insider. Available online: https://www.businessinsider.com/coconut-water-brands-2011-9 (accessed on 12 January 2023).

- Communist Party of Vietnam: Online Newspaper. Vietnam Expects to Earn 1 Billion USD from Coconut Product Exports in 2023. Compiled by BTA. 2023. Available online: https://en.dangcongsan.vn/daily-hot-news/vietnam-expects-to-earn-1-billion-usd-from-coconut-product-exports-in-2023-603206.html (accessed on 5 October 2022).

- Ben Tre Coconut Association. Bentre Coconut Products Export. Ben Tre Coconut Association Website. 2016. Available online: http://www.congthuongbentre.gov.vn/home/tinh-hinh-xuat-khau-cac-san-pham-dua-o-ben-tre-thang-01-2016-W3488.htm (accessed on 5 October 2022).

- Narayan, S.; Bhattacharya, P. Relative export competitiveness of agricultural commodities and its determinants: Some evidence from India. World Dev. 2019, 117, 29–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuo, S.W.; Ranis, G. The Taiwan Success Story: Rapid Growith with Improved Distribution in the Republic of China, 1952–1979; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wardhana, A.K.; Ratnasari, R.T. Impact of Agricultural Land and the Output of Agricultural Products Moderated with Internet Users toward the Total export of Agricultural Product in Three Islamic South East Asian Countries. Iqtishodia J. Ekon. Syariah 2022, 7, 11–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zakaria, M.H.; Amin, M.Z.; Ahmad, M.F.; Dani, M.S. Market potential and competitiveness assessment of Malaysian coconut-based products. Econ. Technol. Manag. Rev. 2022, 18, 11–22. [Google Scholar]

- Narmadha, N.; Karunakaran, K.R. A study on trade competitiveness of Indian Coconut Products. Indian J. Econ. Dev. 2022, 18, 868–875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hebbar, K.B.; Pandiselvam, R.; Beegum, P.P.; Ramesh, S.V.; Manikantan, M.R.; Mathew, A.C. Seventy five years of research in processing and product development in plantation crops-Coconut, arecanut and cocoa. Int. J. Innov. Hortic. 2022, 11, 103–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulyadi, H.; Nazamuddini, B.S.; Seftarita, C. What Determines Exports of Coconut Products? The Case of Indonesia. Int. J. Acad. Res. Econ. Manag. Sci. 2019, 8, 117–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuwornu, J.K.; Moreno, M.L.; Martey, E. Assessment of the factors influencing the export of coconut from the Philippines. Int. J. Value Chain Manag. 2020, 11, 366–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasannath, V. Export performance of coconut sector of Sri Lanka. South Asian J. Soc. Stud. Econ. 2020, 6, 35–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khanh Nguyen, H.T.; Nang Thu, T.T.; Lebailly, P.; Azadi, H. Economic challenges of the export-oriented aquaculture sector in Vietnam. J. Appl. Aquac. 2019, 31, 367–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.A.T.; Nguyen, Q.T.T.; Tran, T.C.; Nguyen, K.A.T.; Jolly, C.M. Balancing the aquatic export supply chain strategy-A case study of the Vietnam pangasius industry. Aquaculture 2023, 566, 739139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NGO, M.; VU, Q.; Liu, R.; Moritaka, M.; Fukuda, S. Challenges for the Development of Safe Vegetables in Vietnam: An Insight into the Supply Chains in Hanoi City; Faculty of Agriculture, Kyushu University: Fukuoka, Japan, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Van Hong, P.; Nguyen, N.T.; Huy, D.T.N.; Thuy, N.T.; Huong, L.T.T. Evaluating several models of quality management and impacts on lychee price applying for Vietnam agriculture products value chain sustainable development. Alinteri J. Agric. Sci. 2021, 36, 122–130. [Google Scholar]

- Tu, V.H.; Kopp, S.W.; Trang, N.T.; Kontoleon, A.; Yabe, M. UK consumers’ preferences for ethical attributes of floating rice: Implications for environmentally friendly agriculture in Vietnam. Sustainability 2021, 13, 8354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Huong, N.; Van Hung, H.; Huyen, M.T.; Diep, N.T.B.; Duc, H.M.; Van Chuong, N. Impact of accession to WTO on agriculture sector in vietnam. AgBioForum 2021, 23, 56–64. [Google Scholar]

- Truong, H.D. A Study to Investigate Possible Advantages of Vietnam in Exporting Agricultural Products to the European Union. 2023. Available online: https://urn.fi/URN:NBN:fi:amk-202305057990 (accessed on 5 October 2022).

- Agbude, E. Changes in the Export Trade Relationship between Vietnam and the US. Master’s Thesis, Norwegian University of Life Sciences, Ås, Norway, 2023. Available online: https://hdl.handle.net/11250/3076790 (accessed on 5 October 2022).

- Hossen, M.A.; Talukder, M.R.A.; Al Mamun, M.R.; Rahaman, H.; Paul, S.; Rahman, M.M.; Miaruddin; Ali, A.; Islam, M.N. Mechanization status, promotional activities and government strategies of Thailand and Vietnam in comparison to Bangladesh. AgriEngineering 2020, 2, 489–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bui, H.T.M.; Nguyen, H.T.T. Factors influencing farmers’ decision to convert to organic tea cultivation in the mountainous areas of northern Vietnam. Org. Agric. 2021, 11, 51–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zainol, F.A.; Arumugam, N.; Daud, W.N.W.; Suhaimi, N.A.M.; Ishola, B.D.; Ishak, A.Z.; Afthanorhan, A. Coconut Value Chain Analysis: A Systematic Review. Agriculture 2023, 13, 1379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoang, V.V.; Tran, K.T. Comparative advantages of alternative crops: A comparison study in Ben Tre, Mekong Delta, Vietnam. AGRIS Online Pap. Econ. Inform. 2019, 11, 35–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ha, V.T.C.; Holmes, M.J.; Le, T.M. Firms and export performance: Does size matter? J. Econ. Stud. 2020, 47, 985–999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Market Watch. Coconut Water Market Size Sale 2021. 2021. Available online: https://www.marketwatch.com/press-release/coconut-water-market-size-sale-2021-regions-will-have-the-highest-revenue-which-will-emerge-in-importance-in-the-market-2026-2021-02-04 (accessed on 5 October 2022).

- Businesswire. World Coconuts Market Analysis, Forecast, Size, Trends and Insights Report 2019. 2019. Available online: https://www.businesswire.com/news/home/20190919005726/en/World-Coconuts-Market-Analysis-Forecast-Size-Trends-and-Insights-Report-2019---ResearchAndMarkets.com (accessed on 5 October 2022).

- Miljkovic, B.; Zizovic, M.; Petojevic, A.; Damljanovic, N. New Weighted Sum Model; Faculty of Sciences and Mathematics, University of Nis, Serbia: Nis, Serbia, 2017; Available online: http://www.pmf.ni.ac.rs/filomat (accessed on 5 October 2022).

- Alinezhad, A.; Khalili, J. New Methods and Applications in Multiple Attribute Decision Making (MADM); Springer International Publishing: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouenniche, J.; Perez-Gladish, B.; Bouslah, K. An out-of-sample framework for TOPSIS-based classifiers with application in bankruptcy prediction. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2018, 131, 111–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vafaei, N.; Ribeiro, R.A.; Camarinha-Matos, L.M. Data normalisation techniques in decision making: Case study with TOPSIS method. Int. J. Inf. Decis. Sci. 2018, 10, 19–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharkasi, N.; Rezakhah, S. A modified CRITIC with a reference point based on fuzzy logic and hamming distance. Knowl.-Based Syst. 2022, 255, 109768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isard, W. Location Theory and Trade Theory: Short-Run Analysis. Q. J. Econ. 1954, 68, 305–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Future Market Insight. Analysis and Review of Coconut Water by Nature–Organic and Conventional for 2020. 2020. Available online: https://www.futuremarketinsights.com/reports/coconut-water-market (accessed on 5 October 2022).

- Grand View Research. Coconut Water Market Size, Share & Trends Report. 2022. Available online: https://www.grandviewresearch.com/industry-analysis/coconut-water-market (accessed on 5 October 2022).

- Salum, U.; Foale, M.; Biddle, J.; Bazrafshan, A.; Adkins, S. Towards the Sustainability of the “Tree of Life”: An Introduction. In Coconut Biotechnology: Towards the Sustainability of the ‘Tree of Life’; Adkins, S., Foale, M., Bourdeix, R., Nguyen, Q., Biddle, J., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahbandeh, M. Coconut Production Worldwide in 2019, by Leading Country. 2021. Available online: https://www.statista.com/statistics/1040499/world-coconut-production-by-leading-producers/ (accessed on 5 October 2022).

- Shahbandeh, M. Coconut Production Worldwide from 2000 to 2019. 2021. Available online: https://www.statista.com/statistics/577497/world-coconut-production/ (accessed on 5 October 2022).

- Tran, T.K. Coconut Value Chain Analysis Report in Ben Tre; IFAD & Ben Tre Province Government People’s Committee: Rome, Italy, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Miller, E. The World’s Top Coconut Producers Face Challenges. Farmfolio. 26 Septemeber 2020. Available online: https://farmfolio.net/articles/the-worlds-top-coconut-producers-face-challenges/ (accessed on 5 October 2022).

- Asia Pacific Coconut Community. Vietnam Coconut Industry. 2021. Available online: http://www.apccsec.org/VIETNAM.HTM (accessed on 20 January 2023).

- Lamoureux, S.M.; Movassaghi, H.; Kasiri, N. The Role of Government Support in SMEs’ Adoption of Sustainability. IEEE Eng. Manag. Rev. 2019, 47, 110–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pai, R.; Chattopadhyay, G.; Karmakar, G. Maintenance and asset management practices of industrial assets: Importance of tribological practices and digital tools. Int. J. Process Manag. Benchmarking 2023, 13, 233–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, N.A.; Ahmed, W.; Waseem, M. Factors influencing supply chain agility to enhance export performance: Case of export-oriented textile sector. Rev. Int. Bus. Strategy 2022, 33, 301–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faroque, A.R.; Ahmed, F.U.; Rahman, M.; Gani, M.O.; Mortazavi, S. Exploring the individual and joint effects of founders’ and managers’ experiential knowledge on international opportunity identification. Asian Bus. Manag. 2022, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yildiz, H.E.; Morgulis-Yakushev, S.; Holm, U.; Eriksson, M. How do the source and context of experiential knowledge affect firms’ degree of internationalization? J. Bus. Res. 2022, 153, 378–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shela, V.; Ramayah, T. Noor Hazlina, A. Human capital and organizational resilience in the context of manufacturing: A systematic literature review. J. Intellect. Cap. 2023, 24, 535–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sayavong, V. Technical inefficiency of the manufacturing sector in Laos: A case study of the firm survey. J. Asian Bus. Econ. Stud. 2022, 29, 314–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donbesuur, F.; Hultman, M.; Oghazi, P.; Boso, N. External knowledge resources and new venture success in developing economies: Leveraging innovative opportunities and legitimacy strategies. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2022, 185, 122034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosein, R.; Satnarine-Singh, N.; Saridakis, G. Analyzing the trade potential of SIDs with a focus on CARICOM’s small resource exporters. J. Int. Trade Econ. Dev. 2023, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; Tao, W. Exploring the complementarity between product exports and foreign technology imports for innovation in emerging economic firms. Eur. J. Mark. 2019, 53, 224–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sunley, P.; Martin, R. Place and industrial development: Paths to understanding? In Handbook of Industrial Development; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2023; Chapter 8; pp. 133–150. [Google Scholar]

- Sakata, S. (Ed.) New Trends and Challenges for Agriculture in the Mekong Region: From Food Security to Development of Agri-Businesses; BRC Research Report; Bangkok Research Center, JETRO Bangkok/IDE-JETRO: Bangkok, Thailand, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Miravitlles, P.; Mora, T.; Achcaoucaou, F. Corporate financial structure and firm’s decision to export. Manag. Decis. 2018, 56, 1526–1540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Risitano, M.; Romano, R.; Rusciano, V.; Civero, G.; Scarpato, D. The impact of sustainability on marketing strategy and business performance: The case of Italian fisheries. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2022, 31, 1538–1551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, R. Innovation or Imitation? The Impacts of Financial Factors on Green and General Research and Development. Int. Rev. Econ. Financ. 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernarto, I.; Purwanto, A. The Effect of Perceived Risk, Brand Image and Perceived Price Fairness on Customer Satisfaction. Brand Image and Perceived Price Fairness on Customer Satisfaction (1 March 2022). 2022. Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=4046393 (accessed on 20 January 2023).

- Pyper, K.; Doherty, A.M.; Gounaris, S.; Wilson, A. Investigating international strategic brand management and export performance outcomes in the B2B context. Int. Mark. Rev. 2019, 37, 98–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, A.W.; Paul, J.; Trott, S.; Guo, C.; Wu, H.H. Two decades of research on nation branding: A review and future research agenda. Int. Mark. Rev. 2021, 38, 46–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, J.; Wang, T.; Jia, Y. and Wang, C.L. How and when do exporters benefit from an international adaptation strategy? The moderating effect of formal and informal institutional distance. Int. Mark. Rev. 2022, 39, 1390–1416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rethinam, P.; Krishnakumar, V. Global Scenario of Coconut and Coconut Water. In Coconut Water; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahzad, U.; Madaleno, M.; Dagar, V.; Ghosh, S.; Doğan, B. Exploring the role of export product quality and economic complexity for economic progress of developed economies: Does institutional quality matter? Struct. Change Econ. Dyn. 2022, 62, 40–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferdous, S.; Ikeda, M. Value creation and competitive advantages for the shrimp industries in Bangladesh: A value chain approach. J. Agribus. Dev. Emerg. Econ. 2018, 8, 518–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Starbucks Stories and News. Starbucks Top 10 Consumer Products and Trends of the Year. 2016. Available online: https://stories.starbucks.com/stories/2016/starbucks-top-10-consumer-products-and-trends-of-2016/ (accessed on 20 January 2023).

- Rethinam, P.; Krishnakumar, V. Coconut Water: A Promising Natural Health Drink-Distribution, Processing and Nutritional Benefits; Springer Nature: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Conway, J. Global Coconut Water Consumption 2009–2015. 2020. Available online: https://www.statista.com/statistics/690202/global-consumption-coconut-water/ (accessed on 20 January 2023).

- Türkcan, K.; Majune Kraido, S.; Moyi, E. Export margins and survival: A firm-level analysis using Kenyan data. S. Afr. J. Econ. 2022, 90, 149–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Souza, J.P.A.; Gómez-Ramírez, L. The paradox of Mexico’s export boom without growth: A demand-side explanation. Struct. Change Econ. Dyn. 2018, 47, 96–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solleder, J.M. Market power and export taxes. Eur. Econ. Rev. 2020, 125, 103425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, T.; Qiu, Y.; Wang, B.; Yang, J. Analysis of effects on the dual circulation promotion policy for cross-border e-commerce B2B export trade based on system dynamics during COVID-19. Systems 2022, 10, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lulaj, E.; Dragusha, B.; Hysa, E. Investigating Accounting Factors through Audited Financial Statements in Businesses toward a Circular Economy: Why a Sustainable Profit through Qualified Staff and Investment in Technology? Adm. Sci. 2023, 13, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hafner, K.A.; Kleinert, J.; Spies, J. Endogenous transport costs and international trade. World Econ. 2023, 46, 560–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murshed, M.; Ahmed, R.; Al-Tal, R.M.; Kumpamool, C.; Vetchagool, W.; Avarado, R. Determinants of financial inclusion in South Asia: The moderating and mediating roles of internal conflict settlement. Res. Int. Bus. Financ. 2023, 64, 101880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morrish, S.C.; Earl, A. Networks, institutional environment and firm internationalization. J. Bus. Ind. Mark. 2021, 36, 2037–2048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, M.E. Competitive Advantage; The Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Cho, H.E.; Lee, J.H.; Jeong, I. Launching new products in international markets: Waterfall versus sprinkler strategy of Korean SMEs. Int. Mark. Rev. 2023, 40, 224–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michel, S.; Saucède, F.; Pardo, C.; Fenneteau, H. Business interaction and institutional work: When intermediaries make efforts to change their position. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2018, 80, 266–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saaty, T.L. The Analytic Hierarchy Prcess; McGraw-Hill International: New York, NY, USA, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Mardani, A.; Jusoh, A.; Nor, K.; Khalifah, Z.; Zakwan, N.; Valipour, A. Multiple criteria decision-making techniques and their applications—A review of the literature from 2000 to 2014. Econ. Res.-Ekon. Istraživanja 2015, 28, 516–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ossadnik, W.; Schinke, S.; Kaspar, H.R. Group aggregation techniques for analytic hierarchy process and analytic network process: A comparative analysis. Group Decis. Negot. 2016, 25, 421–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saaty, T.L.; Vargas, L.G. Models, Methods, Concepts & Applications of the Analytic Hierarchy Process; Springer Science & Business Media: New York, NY, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diakoulaki, D.; Mavrotas, G.; Papayannakis, L. Determining objective weights in multiple criteria problems:The critic method. Comput. Oper. Res. 1995, 22, 763–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jahan, A.; Edwards, K.L. A state-of-the-art survey on the influence of normalization techniques in ranking: Improving the materials selection process in engineering design. Mater. Design. 2014, 65, 335–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishnan, A.R.; Kasim, M.M.; Hamid, R.; Ghazali, M.F. A modified CRITIC method to estimate the objective weights of decision criteria. Symmetry 2021, 13, 973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Industry Leader | Intermediary | Family Business | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Interviewee/Subject | Chief commercial officer | Representative of corporate-level management | Business Owner |

| Size (Annual Production) | 7500 tones | Headquarters in New Zealand | Small business, family-based |

| Market Segment | B2B and mainstream | B2C and B2B Upper-scale, organic | B2B and just started its B2C packaging activities |

| Differentiation Elements |

|

| Quality of raw material and steady supply |

| Distribution Channel |

| Strong distribution channel in New Zealand and some foreign destinations |

|

| Customer Acquisition |

|

| Conventional personal network |

| Organizational Structure | Divisional | Flexible 20 staff members in Vietnam | Two owners, ten employees in total, and growing |

| Target Destinations | U.S market, Brazil, Argentina, Chile, yet focusing on boosting domestic sales | Asian Market, Africa, and Middle East. Aiming to become in the top 5 e-commerce companies by revenue in the U.S by 2025 | Exports to neighboring countries, anticipate growth by an increase in demand for the current network in Europe |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.58 | 0.9 | 1.12 | 1.24 | 1.32 | 1.41 | 1.45 | 1.49 |

| Industrial Assets and Investments (INDUS) | Description and Justification | |

|---|---|---|

| INDUS 1 | Supply of Raw Material | The supply chain of raw materials is described by the level of stability. Environmental changes are the broad-level indicator of supply. |

| INDUS 2 | Dynamic Human Capital in Manufacturing | Sufficient labor supply on the production line equipped with creativity, intellect, and innovation. It also encompasses labor productivity, multifactor productivity, the capital–labor ratio, and experience. |

| INDUS 3 | Modern Manufacturing Technology | Deployment of tangible export-related technology and production innovation capabilities. |

| INDUS 4 | Capital Investment | Firm’s capital investment in improving manufacturing line, processing, and machinery, as well as the provincial budget and banking system supporting the industry, and investment in cultivating processes and farming. |

| Marketing and Sales (MRKT) | ||

| MRKT 1 | Sales Force Readiness | Degree of experience as an indicator of propensity to succeed in communicating with foreign partners; it also includes personnel turnover rate. |

| MRKT 2 | Brand Awareness | The importance of the firm’s branding and planning and the role of country-of-origin branding in target markets. |

| MRKT 3 | Quality of Raw Material | Quality parameters of raw coconut water, like sweetness, water ratio in raw water supply used for manufacturing, as well as freshness. |

| MRKT 4 | Position of Coconut Water in Health Category | Shift in consumption trends toward healthier and diary-free diets with high appreciation for the healthiness, cleanliness, and friendliness to the environment. |

| Potential Profitability (PP) | ||

| PP1 | Growing Demand in Target Markets | Exporting firms’ ability to grow demand in an existing market and create it in new destinations. |

| PP2 | Fluctuating Price of Raw Material | Raw material price uncertainty due to foreign merchants’ intervention |

| PP3 | Trade Agreements Reducing Taxes | Current trade agreements between Vietnam with foreign potential markets including tax reduction agreements and political ties with destination markets. |

| PP4 | Transportation Costs | The dwell and distance costs involved in transporting a given shipment. |

| Foothold in Target Market (TM) | ||

| TM 1 | Distribution Channels in Target Markets | The discovery of new partners to build and expand a network of reliable distributors in target markets. |

| TM 2 | Competition Intensity | Rivals within the industry in the target market, especially with higher production capital. |

| TM 3 | Reliable Sources of Knowledge on Target Markets | Reliable sources of information in foreign markets. |

| Intermediary | Industry Leader | Family Business | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| INDUS 1 | INDUS 2 | INDUS 3 | INDUS 4 | INDUS 1 | INDUS 2 | INDUS 3 | INDUS 4 | INDUS 1 | INDUS 2 | INDUS 3 | INDUS 4 | |

| INDUS 1 | 1 | 0.50 | 0.50 | 0.33 | 1 | 1 | 0.33 | 0.33 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 1 |

| INDUS 2 | 2 | 1 | 0.50 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0.33 | 0.33 | 0.5 | 1 | 0.5 | 0.5 |

| INDUS 3 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 0.5 | 2 | 1 | 2 |

| INDUS 4 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 0.5 | 1 |

| MRKT1 | MRKT2 | MRKT3 | MRKT4 | MRKT1 | MRKT2 | MRKT3 | MRKT4 | MRKT1 | MRKT2 | MRKT3 | MRKT4 | |

| MRKT 1 | 1 | 0.50 | 3 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 1 |

| MRKT 2 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 2 | 0.50 | 1 | 0.50 | 2 | 0.50 | 1 | 0.50 | 1 |

| MRKT 3 | 0.33 | 0.33 | 1 | 0.50 | 0.50 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 0.50 | 2 | 1 | 0.50 |

| MRKT 4 | 0.33 | 0.50 | 2 | 1 | 0.33 | 0.50 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 |

| PP 1 | PP 2 | PP 3 | PP 4 | PP 1 | PP 2 | PP 3 | PP 4 | PP 1 | PP 2 | PP 3 | PP 4 | |

| PP 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 0.50 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 2 | 2 |

| PP 2 | 0.50 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 0.50 | 1 | 0.50 | 1 | 0.33 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| PP 3 | 1 | 0.50 | 1 | 0.50 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 0.50 | 0.50 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| PP 4 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 0.50 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 0.50 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Industry Leader | Intermediary | Family Business | ||||||||||

| TM1 | TM 2 | TM 3 | TM1 | TM 2 | TM 3 | TM1 | TM 2 | TM 3 | ||||

| TM1 | 1 | 3 | 3 | 1 | 0.50 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||

| TM 2 | 0.33 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0.50 | |||

| TM 3 | 0.33 | 0.50 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | |||

| INDUS1 | INDUS2 | INDUS3 | INDUS4 | MRKT1 | MRKT2 | MRKT3 | MRKT4 | PP1 | PP2 | PP 3 | PP 4 | TM1 | TM2 | TM3 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.9990 | 0.8847 | 0.9544 | 0.9288 | 0.8844 | 0.7604 | 0.8684 | 0.9793 | 0.8900 | 0.9264 | 0.9264 | 0.8921 | 0.6106 | 0.8234 | 0.8078 | |

| 1.0000 | 1.0000 | 1.0000 | 1.0000 | 1.0000 | 1.0000 | 1.0000 | 1.0000 | 1.0000 | 1.0000 | 1.0000 | 1.0000 | 1.0000 | 1.0000 | 1.0000 | |

| 0.7657 | 0.9825 | 0.9041 | 0.8539 | 0.9071 | 0.9738 | 0.9705 | 0.8510 | 0.9021 | 0.9948 | 0.9511 | 0.9493 | 0.9212 | 0.8349 | 0.9040 |

| INDUS1 | INDUS2 | INDUS3 | INDUS4 | MRKT1 | MRKT2 | MRKT3 | MRKT4 | PP1 | PP2 | PP 3 | PP 4 | TM1 | TM2 | TM3 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.1259 | 0.2343 | 0.3314 | 0.3084 | 0.3192 | 0.4079 | 0.1064 | 0.1665 | 0.2426 | 0.2426 | 0.1716 | 0.3431 | 0.5936 | 0.2493 | 0.1571 | |

| 0.1250 | 0.1250 | 0.3750 | 0.3750 | 0.4287 | 0.1937 | 0.2304 | 0.1472 | 0.3431 | 0.1716 | 0.2426 | 0.2426 | 0.2599 | 0.4126 | 0.3275 | |

| 0.3369 | 0.1416 | 0.2833 | 0.2382 | 0.3407 | 0.1703 | 0.2026 | 0.2865 | 0.4326 | 0.1766 | 0.1954 | 0.1954 | 0.3275 | 0.2599 | 0.4126 |

| Group Criteria Weights | Criteria | Description | Intra-Criteria | Inter-Criteria | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Weights | Ranks | Weights | Ranks | |||

| 18.22% | INDUS 1 | Supply Chain Network | 0.5006 | 1 | 0.1033 | 4 |

| INDUS 2 | Dynamic Human Capital in Manufacturing | 0.2347 | 2 | 0.0489 | 10 | |

| INDUS 3 | Modern Manufacturing Technology | 0.1049 | 4 | 0.0190 | 15 | |

| INDUS 4 | Capital Investment | 0.1598 | 3 | 0.0329 | 12 | |

| 25.66% | MRKT 1 | Sales Force Readiness | 0.1783 | 4 | 0.0475 | 11 |

| MRKT 2 | Brand Awareness | 0.4178 | 1 | 0.1093 | 3 | |

| MRKT 3 | Quality of Raw Material | 0.2033 | 2 | 0.0539 | 8 | |

| MRKT 4 | Position of Coconut Water in Health Category | 0.2006 | 3 | 0.0535 | 9 | |

| 20.28% | PP 1 | Growing Demand in Target Markets | 0.3934 | 1 | 0.0805 | 5 |

| PP 2 | Fluctuating Price of Raw Martial | 0.1564 | 3 | 0.0320 | 13 | |

| PP 3 | Trade Agreements Reducing Taxes | 0.1417 | 4 | 0.0291 | 14 | |

| PP 4 | Transportation Costs | 0.3085 | 2 | 0.0631 | 7 | |

| 35.84% | TM1 | Distribution Channels in Target Market | 0.4543 | 1 | 0.1410 | 1 |

| TM 2 | Competition Intensity | 0.2152 | 3 | 0.0760 | 6 | |

| TM 3 | Reliable Sources of Information on Target Markets | 0.3305 | 2 | 0.1100 | 2 | |

| Leader | Family Business | Intermediary | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Criteria | Intra- Criteria | Inter- Criteria | Intra- Criteria | Inter- Criteria | Intra- Criteria | Inter- Criteria |

| INDUS 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 4 | 1 | 4 |

| INDUS 2 | 3 | 9 | 3 | 11 | 2 | 10 |

| INDUS 3 | 4 | 13 | 4 | 13 | 4 | 15 |

| INDUS 4 | 2 | 7 | 2 | 9 | 3 | 12 |

| MRKT 1 | 4 | 10 | 4 | 12 | 4 | 11 |

| MRKT 2 | 1 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 3 |

| MRKT 3 | 3 | 8 | 3 | 10 | 2 | 8 |

| MRKT 4 | 2 | 6 | 2 | 8 | 3 | 9 |

| PP 1 | 1 | 11 | 1 | 5 | 1 | 5 |

| PP 2 | 3 | 14 | 3 | 14 | 3 | 13 |

| PP 3 | 4 | 15 | 4 | 15 | 4 | 14 |

| PP 4 | 2 | 12 | 2 | 7 | 2 | 7 |

| TM1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| TM 2 | 2 | 4 | 3 | 6 | 3 | 6 |

| TM 3 | 3 | 5 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 2 |

| INDUS1 | INDUS2 | INDUS3 | INDUS4 | MRKT1 | MRKT2 | MRKT3 | MRKT4 | PP1 | PP2 | PP 3 | PP 4 | TM1 | TM2 | TM3 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| i | D | i | D | D | D | i | j | j | D | i | D | D | D | j | |

| benefit | cost | benefit | cost | cost | cost | benefit | benefit | benefit | cost | benefit | cost | cost | cost | benefit | |

| Expert Criteria Weights | 0.999 | 0.8847 | 0.9544 | 0.9288 | 0.8844 | 0.7604 | 0.8684 | 0.9793 | 0.89 | 0.9264 | 0.9264 | 0.8921 | 0.6106 | 0.8234 | 0.8078 |

| Group Criteria Weight | 0.1822 | 0.1822 | 0.1822 | 0.1822 | 0.2566 | 0.2566 | 0.2566 | 0.2566 | 0.2028 | 0.2028 | 0.2028 | 0.2028 | 0.3584 | 0.3584 | 0.3584 |

| Final Criteria Weight | 0.182 | 0.161 | 0.174 | 0.169 | 0.227 | 0.195 | 0.223 | 0.251 | 0.180 | 0.188 | 0.188 | 0.181 | 0.219 | 0.295 | 0.290 |

| i | 0.192 | j | 0.240 | D | 0.204 | E | 0.225 | ||||||||

| INDUS1 | INDUS2 | INDUS3 | INDUS4 | MRKT1 | MRKT2 | MRKT3 | MRKT4 | PP1 | PP2 | PP 3 | PP 4 | TM1 | TM2 | TM3 | |

| i | D | D | D | D | D | i | j | j | i | D | D | D | D | D | |

| benefit | cost | cost | cost | cost | cost | benefit | benefit | benefit | benefit | cost | cost | cost | cost | cost | |

| Expert Criteria Weights | 0.7657 | 0.9825 | 0.9041 | 0.8539 | 0.9071 | 0.9738 | 0.9705 | 0.851 | 0.9021 | 0.9948 | 0.9511 | 0.9493 | 0.9212 | 0.8349 | 0.904 |

| Group Criteria Weight | 0.1822 | 0.1822 | 0.1822 | 0.1822 | 0.2566 | 0.2566 | 0.2566 | 0.2566 | 0.2028 | 0.2028 | 0.2028 | 0.2028 | 0.3584 | 0.3584 | 0.3584 |

| Final Criteria Weight | 0.140 | 0.179 | 0.165 | 0.156 | 0.233 | 0.250 | 0.249 | 0.218 | 0.183 | 0.202 | 0.193 | 0.193 | 0.330 | 0.299 | 0.324 |

| i | 0.197 | j | 0.201 | D | 0.232 | E | 0.170 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sharkasi, N.; Chau, N.V.H.; Rajasekera, J. Export Potential Analysis of Vietnamese Bottled Coconut Water by Incorporating Criteria Weights of MCDM into the Gravity of Trade Model. Sustainability 2023, 15, 11780. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151511780

Sharkasi N, Chau NVH, Rajasekera J. Export Potential Analysis of Vietnamese Bottled Coconut Water by Incorporating Criteria Weights of MCDM into the Gravity of Trade Model. Sustainability. 2023; 15(15):11780. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151511780

Chicago/Turabian StyleSharkasi, Nora, Nguyen Vo Hien Chau, and Jay Rajasekera. 2023. "Export Potential Analysis of Vietnamese Bottled Coconut Water by Incorporating Criteria Weights of MCDM into the Gravity of Trade Model" Sustainability 15, no. 15: 11780. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151511780

APA StyleSharkasi, N., Chau, N. V. H., & Rajasekera, J. (2023). Export Potential Analysis of Vietnamese Bottled Coconut Water by Incorporating Criteria Weights of MCDM into the Gravity of Trade Model. Sustainability, 15(15), 11780. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151511780