The COVID-19 Pandemic and the Adoption Factors of Film Distribution Business Models in the Context of Sustainability

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Background

3. Literature Review

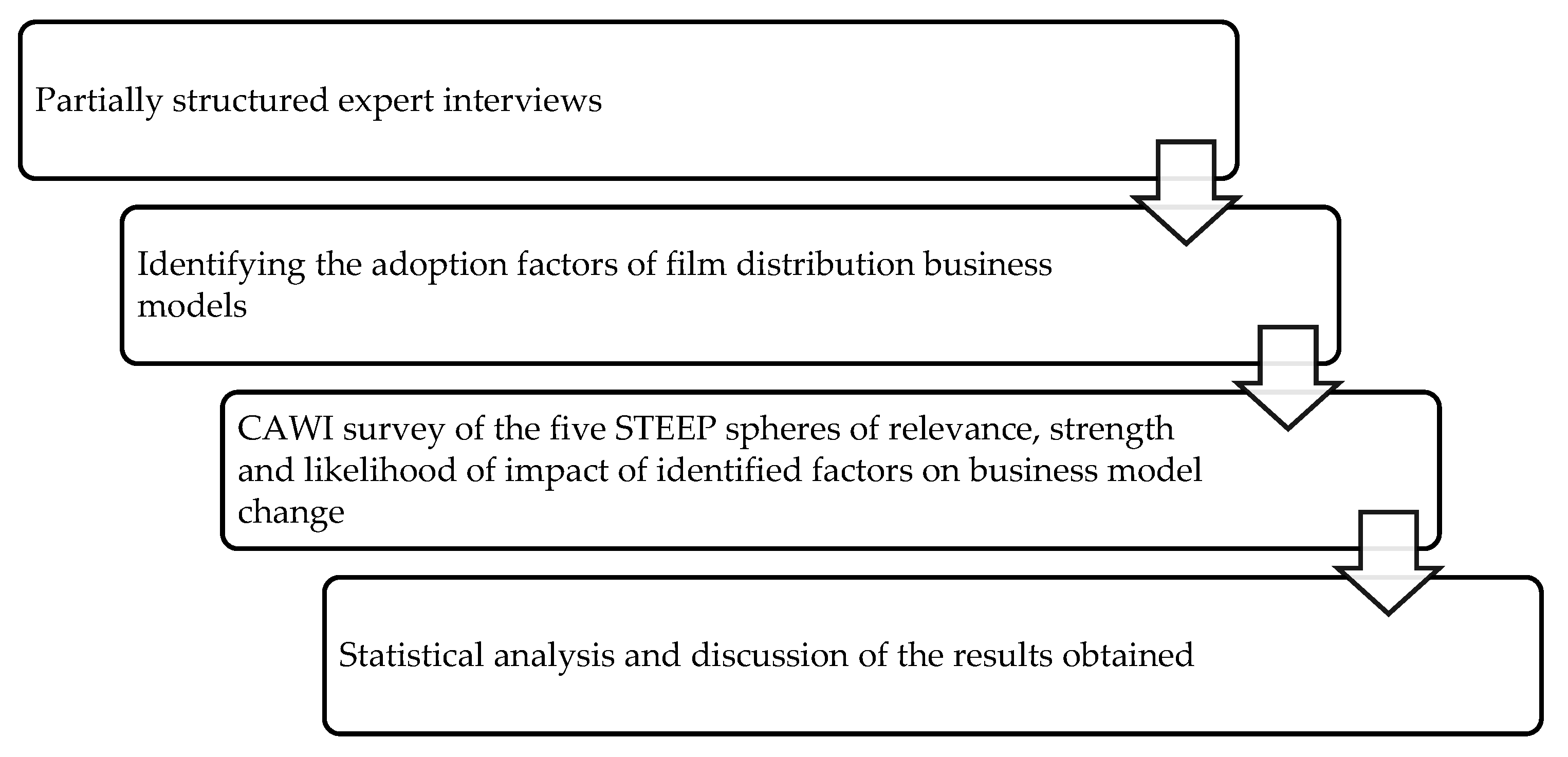

4. Materials and Methods

...the process involved in systematically attempting to look into the longer-term future of science, technology, the economy, and society with the aim of identifying the areas of strategic research and the emerging generic technologies likely to yield the greatest economic and social benefits.

5. Results

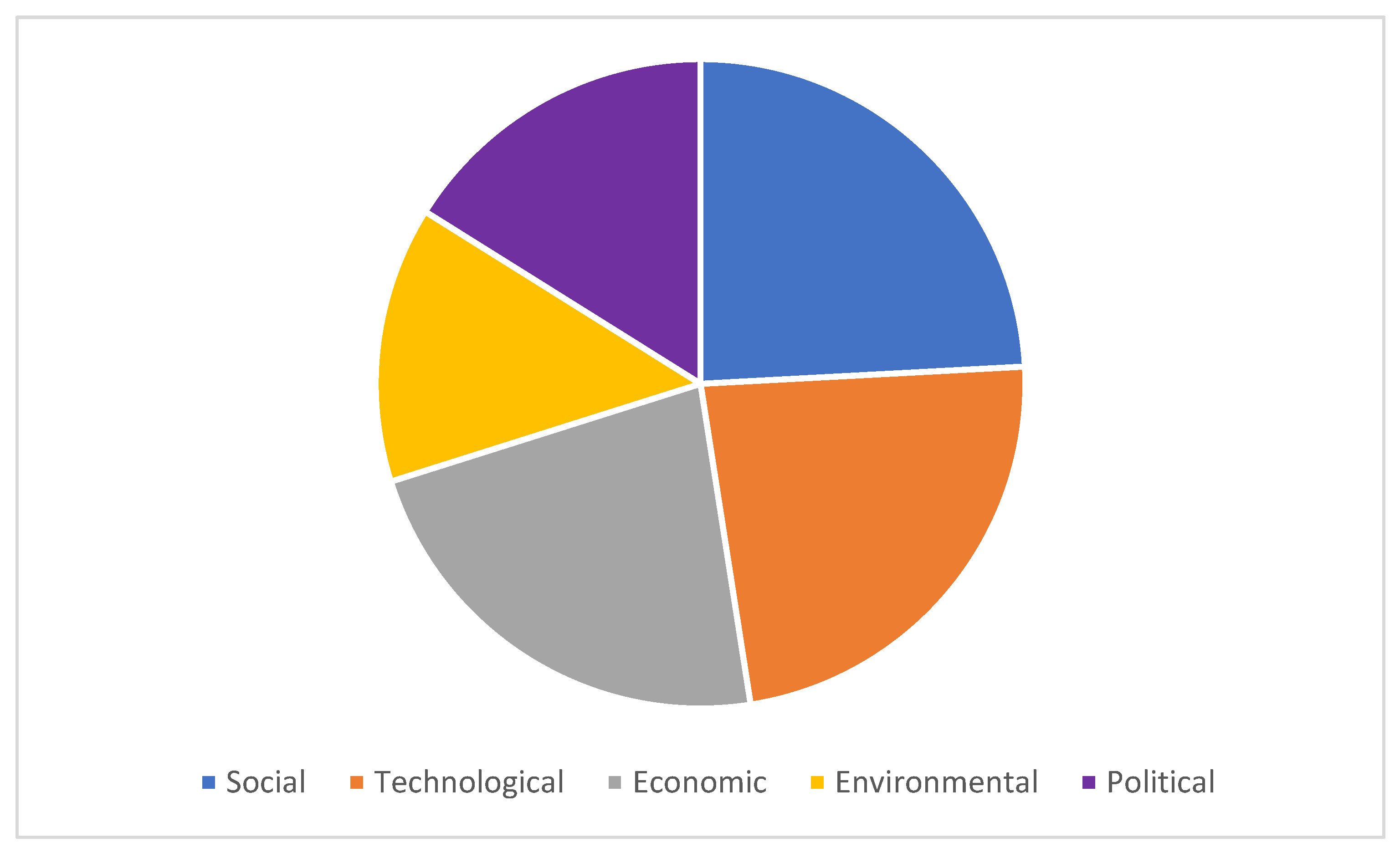

5.1. Identified Factors

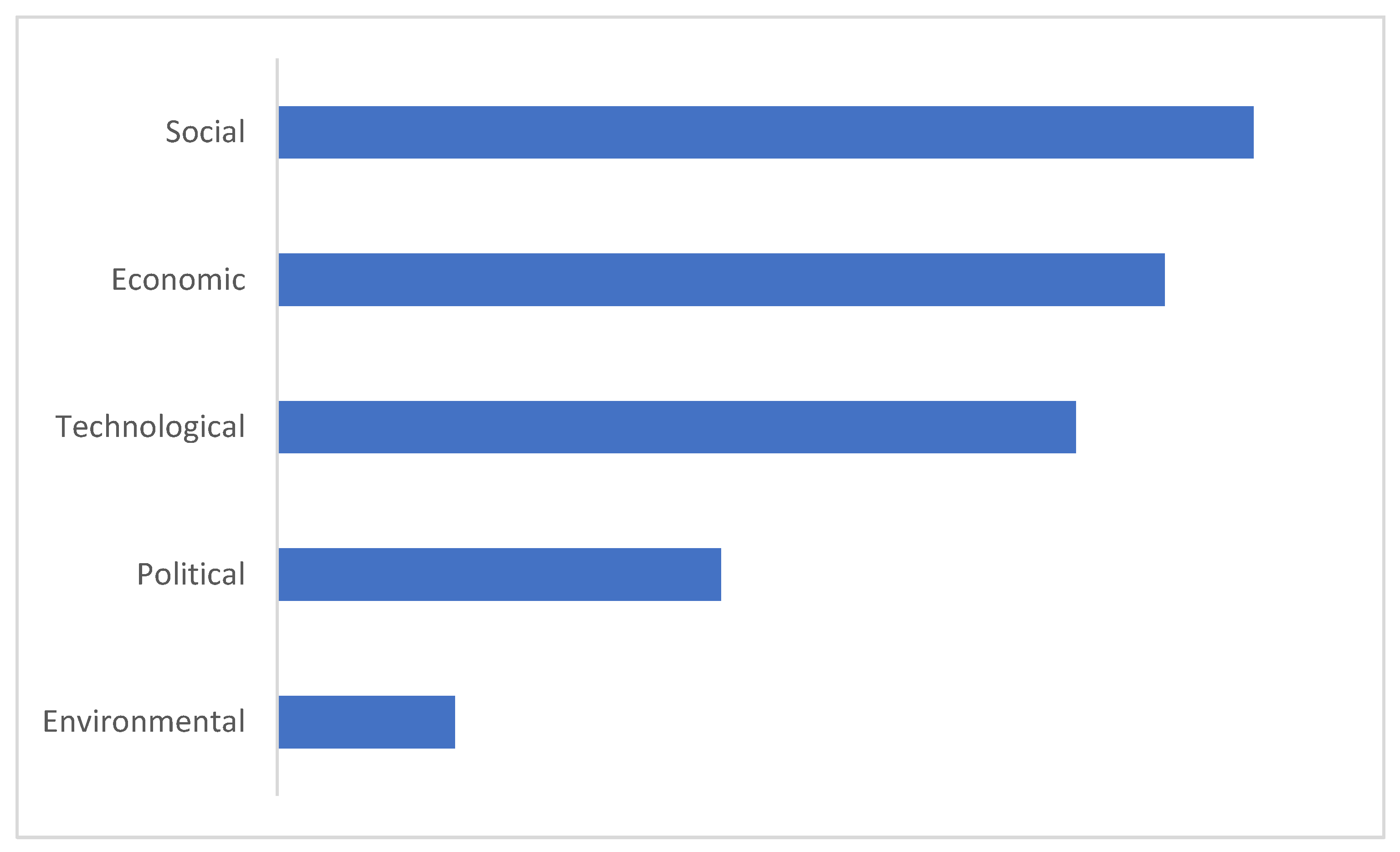

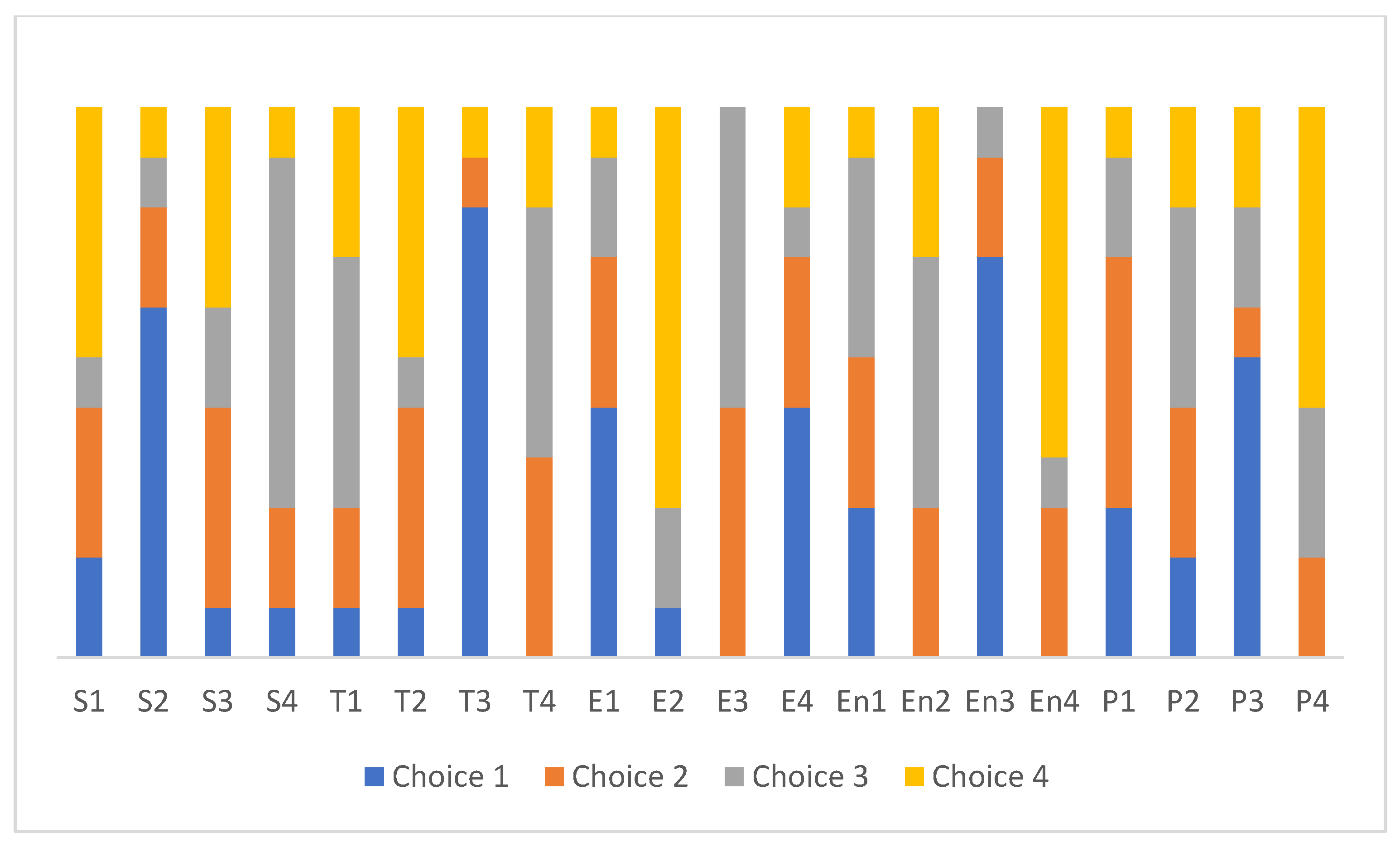

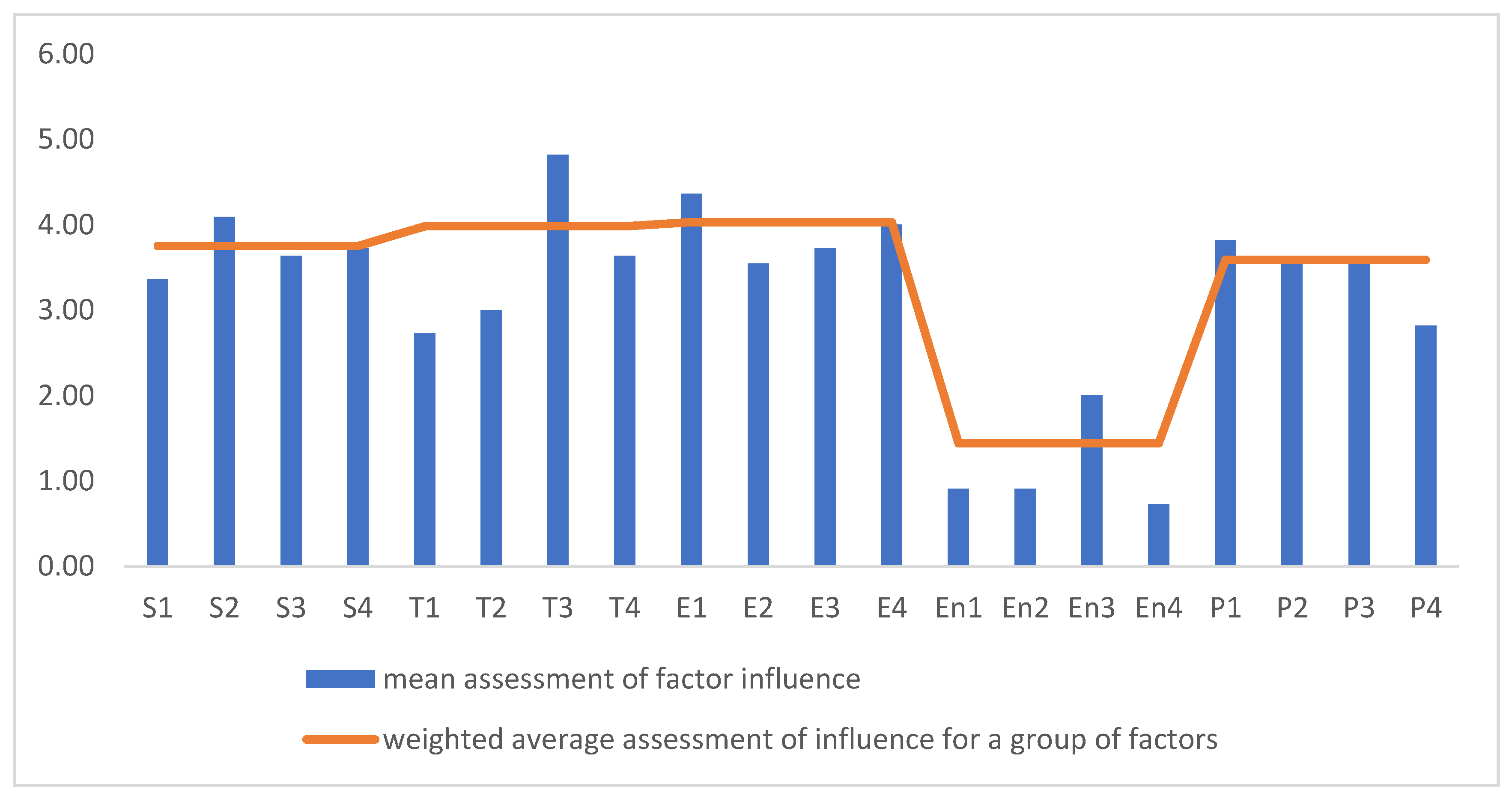

5.2. Results of the Survey

- Social aspect: the comfort of watching a film at home (S2, 64% of responses);

- Technological aspect: internet access (T3, 82% of responses);

- Economic aspect: inflation and viewer purchasing power and subscription prices of streaming platforms (E1 and E4, 45% of responses each);

- Environmental aspect: social ecology (En3, 73% of responses);

- Political aspect: legal and political conditions for the operation of streaming platforms (P3, 55% of responses).

- Social aspect: willingness to experience the event accompanying the screening (S1, 45% of responses);

- Technological aspect: technology used for cinema screening (T2, 45% of responses);

- Economic aspect: cinema maintenance cost (E2, 73% of responses);

- Environmental aspect: green certificates for streaming platforms (En4, 64% of responses);

- Political aspect: public funding for cinemas (P4, 55% of responses).

6. Discussion

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Schumpeter, J.A. Business Cycles: A Theoretical, Historical and Statistical Analysis of the Capitalist Process; McGraw-Hill Book Company, Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 1939. [Google Scholar]

- Clinton, L.; Whisnant, R. Business Model Innovations for Sustainability; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2019; ISBN 9789402411447. [Google Scholar]

- Teece, D.J. Business Models, Business Strategy and Innovation. Long Range Plann. 2010, 43, 172–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chesbrough, H. Business Model Innovation: It’s Not Just about Technology Anymore. Strateg. Leadersh. 2007, 35, 12–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Šimberová, I.; Kita, P. New Business Models Based on Multiple Value Creation for the Customer: A Case Study in the Chemical Industry. Sustainability 2020, 12, 3932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markides, C. Disruptive Innovation: In Need of Better Theory. J. Prod. Innov. Manag. 2006, 23, 19–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bucherer, E.; Eisert, U.; Gassmann, O. Towards Systematic Business Model Innovation: Lessons from Product Innovation Management. Creat. Innov. Manag. 2012, 21, 183–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamel, G. Leading the Revolution; Harvard Business School Press: Boston, MA, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- McGrath, R.G. Business Models: A Discovery Driven Approach. Long Range Plann. 2010, 43, 247–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stubbs, W.; Cocklin, C. Conceptualizing a “Sustainability Business Model”. Organ. Environ. 2008, 21, 103–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fjeldstad, Ø.D.; Snow, C.C. Business Models and Organization Design. Long Range Plann. 2018, 51, 32–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pateli, A.G.; Giaglis, G.M. A Research Framework for Analysing EBusiness Models. Eur. J. Inf. Syst. 2004, 13, 302–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adamczak, M.; Salomon, S. Kruszenie Globalnego Hollywood. Kwart. Film. 2019, 108, 243–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silver, J.; McDonnell, J. Are Movie Theaters Doomed? Do Exhibitors See the Big Picture as Theaters Lose Their Competitive Advantage? Bus. Horiz. 2007, 50, 491–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, T. Global Hollywood; British Film Institute: London, UK, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Miller, T. Global Hollywood 2010. Int. J. Commun. 2007, 1, 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Adamczak, M. Globalne Hollywood; Wydawnictwo Słowo/Obraz Terytoria: Gdańsk, Poland, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Goldsmith, B.; Ward, S.; O’Regan, T. Global and Local Hollywood. InMedia 2011, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Changsong, W.; Kerry, L.; Marta, R.F. Film Distribution by Video Streaming Platforms across Southeast Asia during COVID-19. Media Cult. Soc. 2021, 43, 1542–1552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kucia, K. Nowe Formy Dystrybucji Polskich Filmów Fabularnych. Stud. Medioznawcze 2016, 3, 109–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adamczak, M. Hard Power and Film Distribution: Transformation of Distribution Practices in Poland in the Era of Digital Revolution. Stud. East. Eur. Cine. 2020, 11, 243–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stańczyk, M. Ślad Węglowy Kina. Ekrany 2020, 2, 14–19. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, K. Internet-Based Distribution of Digital Videos: The Economic Impacts of Digitization on the Motion Picture Industry. Electron. Mark. 2001, 11, 273–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kehoe, K.; Mateer, J. The Impact of Digital Technology on the Distribution Value Chain Model of Independent Feature Films in the UK. JMM Int. J. Media Manag. 2015, 17, 93–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grundström, H. What Digital Revolution? Cinema-Going as Practice. J. Audience Recept. Stud. 2018, 15, 5–22. [Google Scholar]

- Schulz, A.; Eder, A.; Tiberius, V.; Solorio, S.C.; Fabro, M.; Brehmer, N. The Digitalization of Motion Picture Production and Its Value Chain Implications. J. Media 2021, 2, 397–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Victoria, A.; Araujo, F. Digital Marketing: Strategies for next-Generation Film Distribution. Int. J. Film Media Arts 2018, 3, 98–123. [Google Scholar]

- Al Kareem, S.S. New Media in Film Distribution in Bangladesh: Bane or Boon? Athens J. Mass Media Commun. 2021, 7, 257–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, W. The Platformization of China’s Film Distribution in a Pandemic Era. Chin. J. Commun. 2022, 15, 95–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruback, G.; Ryan, M. The COVID-19 Pandemic v Black Widow: The Pressure for Change in Film Distribution. Entertain. Law Rev. 2022, 33, 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Knobloch, P.M. Business Model Innovation in the Film Industry: How Nordic Film Studios Adapt to a Changing Market. KTH Vetensk. Och Konst 2021, 1–20. Available online: https://www.diva-portal.org/smash/get/diva2:1592832/FULLTEXT01.pdf (accessed on 19 June 2023).

- Ruddin, I.; Santoso, H.; Indrajit, R.E.; Dazki, E. Big Entertainment’S Film and Music Creation Design: Platform-Based Business Model Canvas and Enterprise Architecture. Capture J. Seni Media Rekam 2021, 13, 3946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulla, T. Assessing the Factors Influencing the Adoption of Over-the-Top Streaming Platforms: A Literature Review from 2007 to 2021. Telemat. Inform. 2022, 69, 101797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Höse, K.; Süß, A.; Götze, U. Sustainability-Related Strategic Evaluation of Business Models. Sustainability 2022, 14, 7285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eliashberg, J.; Elberse, A.; Leenders, M.A.A.M. The Motion Picture Industry: Critical Issues in Practice, Current Research, and New Research Direction. Mark. Sci. 2006, 25, 638–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simon, J.P.; Benghozi, P.J.; Salvador, E. The New Middlemen of the Digital Age: The Case of Cinema. Info 2015, 17, 97–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartosiewicz, A.; Orankiewicz, A. Współczesny Rynek Dystrybucji Kinowej w Polsce. Kwart. Film. 2019, 108, 232–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stempień, J.R.; Rostocki, W.A. Wywiady Eksperckie i Wywiady Delfickie w Socjologii-Możliwości Wykorzystania. Przykłady Doświadczeń Badawczych. Przegląd Socjol. 2013, 62, 73–86. [Google Scholar]

- Bartosiewicz, A.; Orankiewicz, A. The Impact of Hollywood Majors on the Local Film Industry. The Case of Poland. Creat. Ind. J. 2020, 13, 288–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giaoutzi, M.; Sapio, B. In Search of Foresight Methodologies: Riddle or Necessity. In Recent Developments in Foresight Methodologies; Springer: Boston, MA, USA, 2013; pp. 3–9. [Google Scholar]

- Marinković, M.; Al-Tabbaa, O.; Khan, Z.; Wu, J. Corporate Foresight: A Systematic Literature Review and Future Research Trajectories. J. Bus. Res. 2022, 144, 289–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abadie, F.; Friedewald, M.; Matthias Weber, K. Adaptive Foresight in the Creative Content Industries: Anticipating Value Chain Transformations and Need for Policy Action. Sci. Public Policy 2010, 37, 19–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kononiuk, A.; Sacio-Szymańska, A.; Gáspár, J. How Do Companies Envisage the Future? Functional Foresight Approaches. Eng. Manag. Prod. Serv. 2017, 9, 21–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rohrbeck, R.; Kum, M.E. Corporate Foresight and Its Impact on Firm Performance: A Longitudinal Analysis. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2018, 129, 105–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, B.R. Foresight in Science and Technology. Technol. Anal. Strateg. Manag. 1995, 7, 139–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nwankwo, N.; Olaniyi, T.K.; Morgan, A. STEEP Analysis of Energy System Transition to Sustainability. Int. J. Sustain. Energy 2022, 10, 492–501. [Google Scholar]

- Bartosiewicz, A.; Szterlik, P. The STEEPVL and Scenario Analyses of the Development of the Belt and Road Initiative in Poland. Innov. Eur. J. Soc. Sci. Res. 2022, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F. The Digital Transformation of Business Models in the Creative Industries: A Holistic Framework and Emerging Trends. Technovation 2020, 92–93, 102012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salvador, E.; Simon, J.P.; Benghozi, P.J. Facing Disruption: The Cinema Value Chain in the Digital Age. Int. J. Arts Manag. 2019, 22, 25–40. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, I.K. The Impact of Social Distancing on Box-Office Revenue: Evidence from the COVID-19 Pandemic; Quantitative Marketing and Economics; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2021; Volume 19, ISBN 1112902009230. [Google Scholar]

- Gaustad, T. How Streaming Services Make Cinema More Important. Nord. J. Media Stud. 2019, 1, 67–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basile, V.; Capobianco, N.; Vona, R. The Usefulness of Sustainable Business Models: Analysis from Oil and Gas Industry. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2021, 28, 1801–1821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lüdeke-Freund, F.; Carroux, S.; Joyce, A.; Massa, L.; Breuer, H. The Sustainable Business Model Pattern Taxonomy—45 Patterns to Support Sustainability-Oriented Business Model Innovation. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2018, 15, 145–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiménez-Morales, M.; Lopera-Mármol, M. Greening and Celebrification: The New Dimension of Celebrities through Green Production Advocacy. Sustainability 2022, 14, 16843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keilbach, J.; Pabiś, M. Green ( Ing ) Media ( Studies ). NECSUS_Eur. J. Media Stud. 2021, 10, 105–112. [Google Scholar]

- Lopera-Mármol, M.; Jiménez-Morales, M. Green Shooting: Media Sustainability, a New Trend. Sustainability 2021, 13, 3001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meilani, M. Sustainability and Eco-Friendly Movement in Movie Production. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2021, 794, 012075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lupu, R.; Komorowski, M.; Lewis, J.; Mothersdale, G.; Pepper, S. Greening the Audiovisual Sector: Towards a New Understanding through Innovation Practices in Wales and Beyond. Sustainability 2023, 15, 2975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Authors/Year | Method | Research Areas/Factors Discussed |

|---|---|---|

| (Mulla, 2022) [33] | literature review | identification of factors affecting streaming platforms: content, price, flexibility, convenience, perceived usefulness, perceived pleasure, desire to be free of all constraints, entertainment, value, socialisation, cultural inclusion, compulsive viewing, and self-efficacy |

| (Ruback and Ryan, 2022) [30] | literature review, case study | film distribution windows, development of streaming platforms, “day-and-date” strategy |

| (Su, 2022) [29] | literature review, industry reports, case study | impact of digital platforms, changing audience habits, the role of the internet, online video distribution windows, promotional strategies, smart cinema application |

| (Al Kareem, 2021) [28] | interviews | changing consumer habits, “ultra-VOD” and “day-and-date” distribution, the role of the internet, advertising, and innovation in creating sales strategies, content- and device-driven strategies |

| (Changsong et al., 2021) [19] | literature review, interviews | development of streaming platforms, changes in audience habits |

| (Knobloch, 2021) [31] | case studies, semi-structured interviews | distribution channels, revenue streams, margins, network of partners, customer needs and behaviour, products offered, market competition |

| (Ruddin et al., 2021) [32] | literature review | utility, entertainment, social, design, and m-commerce applications; consumer behaviour |

| (Schulz et al., 2021) [26] | Delphi study | forecast of technological changes in the film industry, implications for the value chain |

| (Adamczak, 2020) [21] | industry reports, statistical analysis, semi-structured interviews | digitisation and its impact on distribution costs, the number of titles screened or the shortening of cinema distribution windows |

| (Stańczyk, 2020) [22] | literature review | material, social, and mental (perceptual) ecology, carbon footprint of cinema, film productions and streaming, energy policy of VOD providers, locating environmentally responsible attitudes, green certificates |

| (Victoria and Araujo, 2018) [27] | literature review, interviews, case study | the mutual relationship between media producer and consumer, the restructuring of the film value chain, including technological changes and the reduction of distribution costs |

| (Grundström, 2018) [25] | online questionnaire, semi-structured interviews | social functions of going to the cinema, technological development and going to the cinema |

| (Kucia, 2016) [20] | literature review | technological developments, ways of making films available, advertising strategies, “ultra-VOD” and “day-and-date” distribution |

| Social Factors | |

|---|---|

| S1 | Willingness to experience the event accompanying the screening (e.g., 4D, meetings with artists) |

| S2 | The comfort of watching a film at home |

| S3 | Getting used to streaming platforms |

| S4 | Size of the film offer |

| Technological factors | |

| T1 | Home cinema technology |

| T2 | The technology used for cinema screening |

| T3 | Internet access |

| T4 | Capacity and availability of servers, disks, and databases in use |

| Economic factors | |

| E1 | Inflation and viewer purchasing power |

| E2 | Cinema maintenance costs |

| E3 | Cinema ticket prices |

| E4 | Subscription prices for streaming platforms |

| Environmental factors | |

| En1 | Carbon footprint of post-production and cinema broadcasting |

| En2 | Carbon footprint of streaming distribution |

| En3 | Social ecology (e.g., film-generated meanings, places of circulation) |

| En4 | Green certificates for streaming platforms |

| Political factors | |

| P1 | Possibility of a non-cinema premiere of the film |

| P2 | Festival access also open to films distributed only on streaming platforms |

| P3 | The legal and political environment of streaming platforms |

| P4 | Public funding for cinemas |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Orankiewicz, A.; Bartosiewicz, A. The COVID-19 Pandemic and the Adoption Factors of Film Distribution Business Models in the Context of Sustainability. Sustainability 2023, 15, 11721. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151511721

Orankiewicz A, Bartosiewicz A. The COVID-19 Pandemic and the Adoption Factors of Film Distribution Business Models in the Context of Sustainability. Sustainability. 2023; 15(15):11721. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151511721

Chicago/Turabian StyleOrankiewicz, Agnieszka, and Aleksandra Bartosiewicz. 2023. "The COVID-19 Pandemic and the Adoption Factors of Film Distribution Business Models in the Context of Sustainability" Sustainability 15, no. 15: 11721. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151511721

APA StyleOrankiewicz, A., & Bartosiewicz, A. (2023). The COVID-19 Pandemic and the Adoption Factors of Film Distribution Business Models in the Context of Sustainability. Sustainability, 15(15), 11721. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151511721