1. Introduction

Nature-based tourism (NBT) represents a significant sector within global tourism [

1], which may represent approximately 20% of the global tourism market [

2]. In parallel, many natural areas and ecosystems are threatened by challenges related to climate change, biodiversity loss, and anthropogenic activities, calling into question their sustainability [

1,

3].

The growing interest in visiting Protected Areas (PAs) makes them important and popular nature-based tourism destinations, attracting a large number of visitors every year [

4,

5,

6]. PAs are estimated to receive 8 billion visits annually, generating an estimated economic impact of around USD 600 billion [

7]. However, the COVID-19 pandemic and the consequent travel-related restrictions that occurred between 2020 and 2021 presented challenging repercussions for PAs, causing significant negative impacts on the economy, tourism-related services, and wildlife-related crime-fighting [

8,

9].

At the beginning of the pandemic, a drastic reduction in visitors was observed. However, with the evolution of the pandemic situation, several PAs experienced a demand boom due to domestic tourism [

8]. The restrictions on international mobility, the need to escape lockdowns, and the deprivation of leisure and recreational activities in enclosed spaces imposed with social distancing were the motivation to visit intact ecosystems or ecosystems with few changes caused by anthropic action [

8,

9,

10]. Before the pandemic period, PAs were already, in many cases, important tourism destinations that allowed visitors to enjoy physical and mental relaxation and promoted social well-being. These areas re-emerged with increased importance during lockdowns [

11,

12]. Considering this anomalous context, a re-emerging interest based on immersion in nature, active tourism, and adventure visits to rural habitats and natural landscapes [

13] is expected in the next years.

This research evaluates the state-of-the-art in nature-based tourism, summarising scientific publications in the last decades and identifying trends in scientific research in the study area. For this purpose, an analysis of scientific publications, based on bibliometric tools such as the Bibliometrix and VOSviewer tools, was performed. The bibliometric methodology adds scientific rigour because it is a solid support basis for research, enabling researchers to obtain an aggregated view [

14] and a summarisation of a large amount of information based on transparent and reproducible statistical parameters [

15]. Furthermore, these tools were used since they allow for the discovery of general trends and needs [

16], an understanding of research standards [

17], and identifying trends regarding specific themes [

14].

Consequently, the primary objective of this research is to offer comprehensive insights and considerations for scholars, researchers, and managers involved in the field of PAs and NBT using the research findings. This article aims to make a substantial contribution to the holistic understanding of the present state and future trends in NBT on PAs. Furthermore, it seeks to extensively analyse scientific publications in the focal fields of knowledge, to understand the spatial and temporal relation between them, and to provide valuable insights for researchers, practitioners, and policymakers.

1.1. Protected Areas and Nature-Based Tourism: Antagonism of Interests

The International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) defines PAs as “a clearly defined geographical space, recognised, dedicated and managed, through legal or other effective means, to achieve the long-term conservation of nature with associated ecosystem services and cultural values” [

18] (p. 8). PAs can include maritime areas, lakes, rivers, or lands, which were identified as important for nature conservation and are managed for that purpose [

19].

In 2020, approximately 17% of the entire land area and approximately 8% of coastal and marine areas were under conservation measures related to the creation of PAs or other conservation measures [

20]. Currently, PAs are created with more complex and transversal purposes than those in the past. Conservation of the landscape value of land and maritime PAs, as well as of habitats and biodiversity, continues to be essential. However, the current management goals for PAs include educational, scientific, and cultural purposes, as well as the availability of environmental services and the sustainable use of resources from natural ecosystems [

21]. PAs are also promoters of many benefits in terms of physical health [

22,

23], psychological health [

23,

24,

25], and countless sociocultural benefits [

23,

26]. Currently, the classification of these areas also plays an important role in different contexts and levels, namely, the quality of life for local populations (e.g., [

27,

28,

29]), the creation of new economic dynamics with investment in tourism development (e.g., [

30,

31,

32]), and the essential task of mitigating and adapting to climate change (e.g., [

33,

34,

35]).

The antagonism of interests and the paradox between use and conservation continue to be strongly present. On the one hand, PAs were created to protect and conserve nature; on the other hand, they are attractive and promote visits and profit [

36,

37]. There are PAs that were created in inhabited environments where, currently, there is a union between human activities and the conservation of biodiversity and natural ecosystems. This type of PAs is more frequent in Europe, which offers accommodation, restaurants, and recreational activities inside PAs that are integrated into the rural environment. As a counterpoint, there are countries, such as the United States and Brazil, where PAs were created in natural habitats without human activity present in their interior. The management policy of these areas is dedicated to biodiversity conservation and the environmental education of the visitors. The relationship between tourism and PAs has always been based on an attempt to balance economic development and the protection and conservation of PAs, which makes it complex. The sustainability of these areas requires a trade-off between two objectives: protecting the essential values of environmental preservation and providing visitors with access to enjoy and appreciate those values [

38]. These two objectives should not be seen only as conflicting elements but also as purposes that, when managed with balance, may result in mutual benefits and the support of stakeholders [

30]. However, without full consideration of the environmental and social consequences, in many cases, conservation may effectively be replaced with economic development [

39]. Still, tourism can promote an essential connection between visitors and the values of PAs, becoming a potentially positive strength for conservation [

5]. The tourism sector takes on, in many cases, a significant role in the conservation and preservation of PAs including generating economic and social benefits, which are essential elements for the revenue generated from protected natural areas and for financing conservation and local livelihoods [

5,

40]. Several studies analysed this phenomenon in different countries, such as Portugal [

41,

42,

43], Kenya [

44,

45], Spain [

21,

44,

45], China [

46,

47,

48], and India [

48,

49].

1.2. Ambiguity in NBT Terminology

NBT has been a popular topic in the literature in the last decades [

50,

51]. The concept of NBT is comprehensive and often related to other terms present in the literature. For example, several authors use the terms NBT and ecotourism as synonyms [

52]. Others use the term NBT as a synonym for rural, sustainable, responsible, or adventure tourism [

53,

54]. However, the appropriate distinctions should be made. NBT is traditionally defined using characteristics of the product or the context in which it is integrated, while terminologies such as “responsible tourism”, “ecotourism”, or “sustainable tourism”, are defined using characteristics that include positive impacts on the social and/or environmental levels [

55]. On the other hand, since NBT has a wide range, any tourism activity performed by a person, outside its usual framework, in underdeveloped or less modified natural areas or natural landscapes may be considered NBT [

56]. Therefore, NBT covers every type of tourism where the main attraction is nature or outdoor activities in the context of nature [

57,

58]. Usually, this type of tourism includes trips close to or inside parks, forests, lakes, the sea, or rural areas to participate in activities using resources that are compatible with the natural quality of those places [

59]. These activities include: enjoying landscapes, natural scenarios, and fauna and flora; outdoor recreation and adventure (e.g., rafting, backpacking, and cycling); hunting and fishing; nature conservation volunteer tourism; and ecotourism [

56,

60]. Within this framework, we can also consider adventure tourism, outdoor tourism, and responsible tourism as eventual NBT subcategories when these activities are effectively performed in natural landscapes and areas.

In addition, the International Ecotourism Society (TIES) defines the concept of ecotourism that is narrower than the concept of NBT [

61]. As an NBT segment, ecotourism may be defined as responsible travel to natural areas that conserves and preserves the environment, sustains the well-being of the local people, and involves interpretation, education, and inclusion [

61]. Donohoe & Needham [

62] prepared a review of several definitions for ecotourism present in the literature and reached a consensus necessary to operationalise the concept. The authors came to the conclusion that the concept of ecotourism should integrate six core characteristics: (1) nature-based; (2) preservation and conservation; (3) education; (4) sustainability; (5) distribution of benefits; and (6) ethics/responsibility/awareness [

62]. Therefore, the concept may be seen as a normative subcategory of NBT [

63]. Since ecotourism is a strong component of environmental preservation and protection, ecotourism activities are especially connected to promoting the preservation of natural resources using the education and awareness of local communities, tourists, and other stakeholders [

52,

61,

64,

65]. Within this framework, assuming that all tourism that takes place outdoors and that involves nature is “ecotourism” is particularly problematic [

36].

Another frequent term in the literature is related to rural tourism. The World Tourism Organization (UNWTO) defines the concept as “a type of tourism activity in which the visitor’s experience is related to a wide range of products generally linked to nature-based activities, agriculture, rural lifestyle/culture, angling and sightseeing” [

61]. Although there is a major relationship between rural tourism and NBT, rural tourism products revolve specifically around the resources that include cultural and rural lifestyle elements, such as agriculture, historical sites, living heritage, rural customs, folklore, and traditions [

61,

66]. Therefore, as in the other previously described examples, we consider rural tourism as an NBT subcategory.

2. Materials and Methods

The present investigation uses bibliometric tools to obtain comprehensive knowledge of scientific research and reveal intellectual structures regarding PAs and NBT in the last thirty years. Today, bibliometric research is a rigorous study that allows the discovery of emerging trends in articles and in the performance of journals, as well as identifying the most influential authors, collaboration patterns, and intellectual structures in different scientific domains [

67,

68,

69]. The scientific articles published between 1991 and 2021, available on the Web of Science (WoS) platform, served as the foundation for conducting this study. The high-quality standards related to scientific research and the need to standardise information required in this type of research [

70] justified the choice to use WoS. It is estimated that between 96% and 99% of the articles indexed in WoS are also indexed in Scopus. However, WoS is a more selective platform regarding the articles it makes available [

71].

The compilation of documents began with the definition of the search criteria, where multiple query strings were used (

Table 1). Only scientific articles written in English were considered. Although other types of documents influence academic thinking, it is reasonable to assume that academic journals are the dominant communication platform for researchers [

72,

73]. The inclusion of a “

$” sign at the end of the words allowed us to obtain records in singular and plural. Due to the different categories of existing PAs, several categories of PAs, as established by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) [

18], were included in the search terms. Other terms regarding other categories of PAs (e.g., nature parks, regional parks), as mentioned by the European Environment Agency [

19], were also included. Using these numerous search criteria, we tried to reduce the possibility of subjective bias when selecting articles for the analysis.

The terms searched, as well as the number of articles obtained, are described in

Table 2. For all the results (

n = 3035) of the searches performed, the custom record with the elements (e.g., author, title, journal, year, volume, number, pages, month, abstract, publisher, address, type, language, affiliation, DOI, ISSN, E-ISSN, keywords, keywords-plus, research-areas, and cited-references) was selected and downloaded from the WoS platform in “.bib” and “.txt” formats. Then, we proceeded to remove duplicate articles from the database (

n = 1219). The next step was a closer inspection of the abstracts and, when necessary, reading the full text to eliminate articles considered irrelevant to our research (

n = 783). Overall, 1033 scientific articles were considered valid for subsequent analysis.

The data analysis process was implemented in three stages. The first stage was developed in Excel, which allowed us to analyse and view the data and obtain detailed knowledge of the content described in the abstract and keywords. The second stage of the analysis was performed using Bibliometrix (version 3.2.1) and VOSviewer (version 1.6.18) software, which allowed us to build a comprehensive analysis of the bibliographic metadata. The Bibliometrix package allowed us to import the bibliographic data (n = 1033) from the WoS database and perform the data analysis. The analysed metadata included: information about the author; the total number of publications; WoS categories; calculation of citations with a total of citations; keywords; countries/regions; and h-index.

The networks were constructed using bibliometric information, such as the co-authorship network by country, the co-occurrence of keywords, the temporal co-occurrence network, and citations, which were derived from scientific articles. The VOSviewer utilises these data to generate visual maps, on which elements are represented as nodes (points) and the relationships between them are depicted as lines or connections. By examining these networks, patterns, trends, and clusters in scientific research can be identified. The nodes can represent institutions or keywords, while the lines or connections indicate the frequency or strength of the relationships between these elements. These networks provide valuable insights into the structure of the scientific community, identifying research groups, centres of excellence, and emerging themes. They facilitate the visualisation of connections across different research areas, promoting the identification of knowledge gaps and opportunities for collaboration. Concerning relational networks, multiple networks were explored; however, only the four most significant and valuable maps are presented in alignment with our research objective.

The first map is related to a co-occurrence analysis of author keywords. This type of analysis is based on the idea that if a set of words is mentioned in different documents, there is a great probability that the concepts behind those words are closely related [

74]. The co-occurrence analysis of author keywords allows for measuring the most common keywords in the documents included in the database [

75]. The presence of several co-occurrences around the same keywords reveals patterns and trends in the study area, using a measurement of the strength of those terms in the publications on the theme under analysis [

76].

The second map represents a co-authorship network by country. Co-authorship represents the degree of collaboration between authors, institutions, or countries. This type of analysis is particularly useful to identify collaborative networks between countries, showing the strength of cooperation and the number of articles these countries publish in co-authorship.

The third map represents an author co-citation network. Co-citation refers to two publications that are cited together in another article [

77]. When two authors are co-cited together, there is often a strong possibility that these two references have something in common [

78] and that there is a close relationship between the authors [

79]. Therefore, an author co-citation network enables the identification and visualisation of the intellectual landscape of a certain academic theme or subject by calculating the frequency at which an author is co-cited by another author in another document [

79].

The fourth map also refers to the analysis of the temporal co-occurrence network of author keywords, which reveals the main trends in the study area between 2011 and 2021. This is the decade during which a substantial increase in publications was simultaneously verified and when more than 80% of the keywords present in the database occurred. According to Donthu et al. [

79], a graphical view of the VOSviewer networks should take into account that each node in the network represents an entity (e.g., keyword); the size of the node indicates the number of times that entity occurs; the link between nodes represents the co-occurrence between entities; and the thickness of the link represents the number of times that an entity occurs or co-occurs together (the thicker the link, the greater the occurrence or co-occurrence between entities). The same interpretation may be transposed to the co-authorship networks and author co-citation networks, given that, in those cases, the links represent the number of publications that two authors co-authored and the number of times the two publications are cited together in another article [

80], respectively.

3. Results

3.1. Scientific Productivity

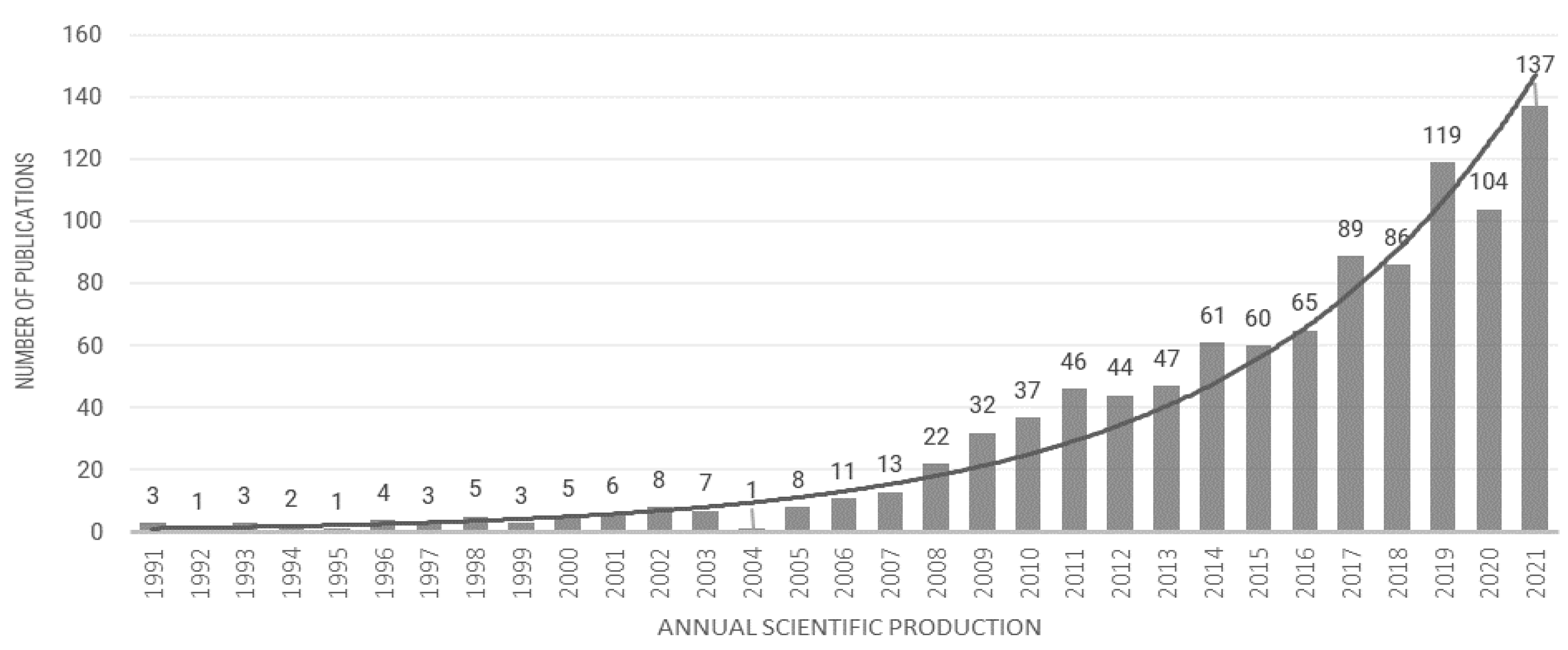

By analysing the number of publications per year that referred to PAs and NBT between 1991 and 2021 (

Figure 1), we observed a substantial increase in publications in the last two decades. Of the 1033 articles analysed, 30 articles were published between 1991 and 2000, 145 were published between 2001 and 2010, and 858 were published between 2011 and 2021.

The increase in scientific publications may be directly correlated with the increase in awareness regarding the importance of biodiversity conservation, the observation of the pressure that exists on natural ecosystems, the proliferation of studies regarding climate change and the importance of PAs, and the development of new techniques for metainformation analysis [

81]. It is important to highlight the United Nations for its role in generating awareness regarding nature conservation. Some of the most important milestones were publishing the First IPCC Assessment Report (FAR) in 1990; approving the Convention on Biological Diversity in 1992, which aimed to preserve biodiversity and promote the sustainable use of biological resources; signing the Kyoto Protocol in 1997, which established the goals to reduce greenhouse gas emissions; and, lastly, creating the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) in 2015.

Regarding the number of publications per WoS category (

Table 3), the most represented categories in the database were Hospitality, Leisure, Sport and Tourism, Environmental Sciences, and Geography. It is important to mention that the database under analysis was framed in 142 different WoS categories, reflecting the great multidisciplinarity in the themes under analysis.

Table 4 presents the top 20 journals per number of article citations in WoS, including the number of publications and the h-index as a reference for productivity and the impact of citations, respectively. From the 387 journals present in the dataset, it was possible to observe that the two journals most highlighted for the three indicators were the

Journal of Sustainable Tourism and

Tourism Management.

3.2. Keyword Analysis

All author keywords (

n = 3124) were analysed, and we were able to identify a large increase in certain keywords, which suggested the areas of research that attracted an extraordinary amount of attention.

Table 5 presents a division of articles and keywords using the three decades under analysis. Using this division, it was possible to verify that the themes of ecotourism and nature conservation were present over the three decades, whereas the themes of sustainable tourism and development were introduced in the last decades. A consolidation of themes developed particularly in the last two decades was also verified, which suggests possible and future evaluative trends within the respective themes.

Given the large number of identified keywords, a minimum threshold of eight keyword occurrences was established. Thus, the co-occurrence analysis found 67 keywords that met the threshold. In

Figure 2, a representation showing the co-occurrence network of author keywords developed using VOSviewer is presented. The most common keywords in the network are represented as major nodes, and the shorter the distance between the nodes, the stronger the relationship between the keywords.

Considering the themes addressed in this study, it comes with no surprise that the keywords that registered a large number of occurrences were “tourism”, “protected areas” and “nature-based tourism”. These three keywords generated nodes with significant size, representing major proportions when compared with the other nodes. One of the major advantages of using VOSviewer is the ability to create data views and respective relations. Therefore, we hid these most common nodes to facilitate the view and allow a better understanding and interpretation of the network and the nodes that comprise it. In addition to these keywords, “ecotourism”, “conservation”, “national parks”, “recreation”, “sustainability”, “development” and “sustainable tourism” were the keywords that registered the largest number of occurrences in the network. These two groups of keywords obtained between 152 and 41 occurrences, respectively, and a total link strength (TLS) between 222 and 46, respectively. Bearing in mind that there were keywords that, due to their redundancy, repetition, and variation, did not add value to the analysis, to facilitate the view and interpretation of the network, another 9 keywords were also removed (e.g., “nature tourism”, “area”, “areas”, “protected”, and “nature-based”).

Therefore, five clusters were identified in the network that contained related keywords. The first cluster (blue) referred to research related to ecotourism, with particular focus on the context of national parks. The second cluster (red) identified studies related to nature conservation, biodiversity, and sustainability. The third cluster (yellow) included the themes of national parks, recreation, and climate change. The fourth cluster (orange) referred to the themes related to sustainable management and development. The fifth cluster (green) included themes related to China, ecosystem services, and resilience.

3.3. Distribution of Articles Geographically and by Organisation

The metadata analysed showed a geographic distribution of the articles based on the affiliation of the authors. The collected articles were distributed by 1221 institutions from 94 different countries, proving the globality of the theme.

Table 6 presents the top 15 countries with major scientific production (63.4% of the total), taking into account the affiliation per country for the corresponding authors. This ranking comprised eight European countries, two Eurasian countries (Russia and Turkey), two American countries, one Asian country, one African country, and one country from Oceania. We observed that the majority of the articles were written by corresponding authors with affiliation to institutions from the USA, China, Australia, Spain, and the UK.

Subsequently, a co-authorship network divided by country was prepared to verify the strength of the collaboration between countries (

Figure 3). It was decided that a minimum number of 10 documents per country was required, and 38 countries met this threshold. To facilitate the interpretation of the network, a minimum number of 10 items per cluster was also established. In this network, the USA emerged as the country with the largest TLS among all countries considered. Therefore, the most relevant country in the network was the USA (citations = 6157, TLS = 135), followed by England (citations = 2460, TLS = 74), China (citations = 2001, TLS = 73), Australia (citations = 3008, TLS = 62), and Germany (citations = 1157, TLS = 54). Based on this network, it was possible to identify two different clusters, where the USA and China occupied the central stage in their respective clusters. It was also possible to verify the strength of the collaborative relationships between countries in terms of research on PAs and NBT, where the cooperation between the USA and China and between the USA and Australia, Canada, England, and South Africa stood out. It is also important to highlight that the only African country in the network is South Africa, which actively collaborates with the USA, Australia, England, and Finland.

Then, we proceeded analyse most relevant organisations in the database (

Table 7). Given that the authors may have several affiliations to different organisations, we accounted for the number of times an affiliation to a certain organisation appeared in the articles under analysis. The three organisations with the most affiliations were Griffith University, Murdoch University, and the University of Waterloo. Two North American universities (Utah and Michigan), three Nordic universities (Oulu, Iceland, and Helsinki), one Eastern European university (Novi Sad, Serbia), and one Chinese university (Beijing Forestry) also stood out.

3.4. Publications by Author and Article Citations

The meta-information aggregated a set of 2577 authors, with the majority (

n = 2406, 93.4%) developing research in partnership with other authors. The number of authors who worked individually was low (

n = 171, 6.6%), which demonstrates the existence of networks of researchers (

Table 2). To find the most active researchers, we proceeded to identify the authors with a larger number of publications. Given that there was a significant number of authors (

n = 13) with five published articles, a threshold of six published articles was included, which returned a result of thirteen authors with more than five published articles.

Table 8 presents the authors with more publications in the database, where Hubert Job (

n = 15), Catherine Pickering (

n = 13), and Lewis Cheung (

n = 9) stood out.

Regarding the articles with a larger number of citations, the top 15 most cited articles are listed in

Table 9. In first place is the article by Spencer Wood, Anne Guerry, Jessica Silver, and Martin Lacayo, published in

Scientific Reports in 2013, which tested the use of big data from social networks in quantifying the rate of visits to 836 recreational places [

82]. In second place is the article by James Beresford, Jonathan Green, Robin Naidoo, Matt Walpole, and Andrea Manica, published in 2009, in PLOS Biology, which analyses the trends in nature-based tourism based on the evolution of the number of visitors in 280 PAs, in 20 different countries [

40]. In third place, we have the article by Andrew Balmford, Jonathan Green, Michael Anderson, James Beresford, Charles Huang, Robin Naidoo, Matt Walpole, and Andrea Manica, published in

PLoS Biology in 2015, which focused on the creation of regional models to predict the rates of visits to PAs and then estimate the number of visits to PAs worldwide, as well as the economic impact generated with those visits [

7].

To understand the connections between citations, an author co-citation network (

Figure 4) was created.

Due to the high number of authors present in the collection and to the interpretation of the network, a minimum number of 30 citations for one author and a minimum number of 3 authors per cluster were established. From here, we obtained a set of 115 selected authors to integrate a network composed of 4 different clusters. The first cluster (red) integrated 48 authors, where Stefan Gossling (TLS = 1022), Kreg Lindberg (TLS = 821), and Matt Walpole (TLS = 809) stood out. The second cluster (green) comprised 30 authors, where Paul Eagles (TLS = 2554), David Weaver (TLS = 2049), and Daniel Scott (TLS = 869) stood out. The third cluster (blue) comprised 21 authors, where Ralf Buckley stood out as the author with the largest TLS in the network (3339). In this cluster, David Newsome (TLS = 2339), Catherine Pickering (TLS = 1571), and David Cole (TLS = 1510) also stood out. Lastly, 16 authors comprised the fourth cluster (yellow), where Hubert Job (TLS = 1662), Colin Hall (TLS = 1522), Marius Mayer (TLS = 1177), and Jarkko Saarinen (TLS = 1140) stood out.

3.5. Territorial Application and Research Methods

Although not all articles included studies specifically applied to a particular PA, in approximately 57% of the articles analysed, it was possible to verify the type of PA the study applied to (

Table 10). Therefore, it was possible to verify that the most studied PA category in the context of the NBT was national parks.

Regarding the research methodologies, it was particularly difficult to quantify the methods used in the articles under analysis with rigour. There was a large multidisciplinarity in the research applied to PAs and NBT, as reflected by the number of WoS categories (

n = 142), with the research methods being multivariate. However, by analysing the collection of articles, it was possible to verify that the choice of a case study design was particularly common (e.g., [

86,

93,

94,

95,

96]). A large number of relevant publications collected data using survey questionnaires (e.g., [

97,

98,

99,

100], interviews and/or focus groups (e.g., [

2,

101,

102,

103,

104]), and mixed methods including the two previous ones (e.g., [

105,

106,

107]) and workshops (e.g., [

108,

109,

110]).

Other popular and relevant methods present in the literature included the use of GIS tools (e.g., [

111,

112,

113]), web-based and social media photos (e.g., [

112,

114,

115,

116]), and other social media content [

82,

83,

117].

3.6. Research Trends

Based on the network of author keywords identified in

Figure 2, the VOSviewer was used to identify the evolution of the keywords in the last decade under analysis (2011–2021). Therefore, it was possible to identify evolution of the themes under analysis, suggesting topics of scientific interest in more recent years (

Figure 5). Considering the darkest nodes of the mentioned network, six themes with particular emphasis were identified in the last years: (1) sustainable tourism; (2) climate change; (3) geotourism and rural tourism; (4) ecosystem services and cultural ecosystem services; (5) visitor studies; and (6) wildlife tourism.

3.6.1. Sustainable Tourism

Sustainability and sustainable development are essential elements of the United Nations 2030 Agenda [

118]. For several years, tourism has been recognised as an essential tool to reach those goals [

119,

120]. Although nature-based tourism can be important to support biodiversity and environmental conservation, excess tourism may have damaging effects on the natural and social environment of territories [

117,

119] and a negative impact on the management of Pas [

121]. Consequently, now more than ever, it is important to develop sustainable tourism practices as a way to increase the resilience of ecological systems and local communities [

122], as well as to promote economic growth, environmental protection, social inclusion, and good governance [

123]. Within this framework, the Sustainable Development Goals became focal points for the study of tourism contributions regarding sustainable development [

123,

124]. The context of PAs should continue to receive great attention from the scientific community, characterised by a large coverage of themes and applications.

3.6.2. Climate Change

The effects of weather and climate conditions on tourism, regarding tourism destinations, include two aspects: the direct impact on tourists (e.g., comfort and weather conditions, which are appropriate for certain activities) and the context effects (e.g., species present, quality, and ecosystem and general environment conditions) [

125]. The connection between climate and tourism is multifaceted and highly complex, and both are intrinsically connected [

126]. Additionally, atypical weather conditions can affect the focus of the tourist attraction (e.g., snow conditions, wildlife biodiversity and productivity, and level and quality of water) [

33,

127,

128,

129,

130,

131]. The environmental conditions that can dissuade tourists are largely influenced by climate and its variability, which can frequently be translated into droughts, wildfires, and high temperatures, as well as the proliferation of infectious diseases, plagues transmitted by insects or water, and different extreme events [

126,

131]. Recent studies focus on understanding the impacts of tourism and climate change on PAs (e.g., [

132]) and the impacts of climate change on NBT (e.g., [

133]) and on changes in visitors’ behaviour (e.g., [

134]).

3.6.3. Geotourism and Rural Tourism

The singularity of certain geological formations and geomorphological landscapes are real tourist attractions in several PAs. In parallel, geotourism is one of the most recent concepts of tourism and one of the largest growing areas in terms of popularity [

135]. Some recent articles on geotourism in PAs include themes such as tourism development and local sustainable development (e.g., [

136,

137,

138]), environmental impact assessment (e.g., [

139]), geotourist profile (e.g., [

140]), visitors’ perspective on geotourism and geotours (e.g., [

141]), and geotrail prospection (e.g., [

142]). Unlike geotourism, rural tourism is not a new concept in the literature. Some themes addressed in the last years were related to sustainable development (e.g., [

143]), sustainable tourism planning and development (e.g., [

144]), attitudes towards rural tourism (e.g., [

145]), tourists’ perceptions (e.g., [

146]), and the relationship between parks and communities (e.g., [

146]).

3.6.4. Ecosystem Services and Cultural Ecosystem Services

The concept of ecosystem services (ESs) can be understood as the benefits generated by ecosystems and obtained and used by human beings [

147]. Within this framework, cultural ecosystem services (CESs) are a subsector of ESs with the particularity of being non-material services, which include physical, intellectual, and spiritual interactions between people and nature [

148]. Consequently, CESs can be seen as the interactions between environmental spaces and cultural and recreational practices and the connections established in those spaces [

149].

Recently, some studies on tourism and ESs in PAs focused on the analysis of different locations and on the identification of different services related to different types of tourism, namely NBT and cultural tourism (e.g., [

149,

150]). Other studies combined scientific knowledge with community knowledge to evaluate and identify the ecosystem services in a certain territory (e.g., [

151]) and promote a more sustainable management of PAs (e.g., [

152]). The literature regarding ecosystem services has been growing exponentially and has infinite potential and applications. For example, there is a noticeable increased interest in the spatial and temporal characterisation of ecosystem services using the analysis of social network data (e.g., [

17]), which allows the evaluation of nature tourist satisfaction or the attractiveness of tourist sites (e.g., [

153]). It also allows quantifying and/or mapping the perceived and aesthetic value of landscapes (e.g., [

154,

155]), finding spatial and temporal patterns based on visits and the mapping of interest points in PAs (e.g., [

150]), and valuing abiotic elements as ecosystem service providers, with their distinction as geosystem services having also been suggested.

3.6.5. Visitor Studies

The themes regarding motivations, satisfaction and segmentation of tourists and visitors are often explored in the tourism literature, in general, and in PAs and NBT, in particular. These studies allow a prediction of visit patterns, travel behaviour, and management effects and represent an essential aspect of PA sustainability [

156,

157,

158]. Recent studies explored several perspectives, namely satisfaction in terms of ecotourism experiences (e.g., [

159]), satisfaction and over-tourism (e.g., [

160]), impacts of the perceived value of services on satisfaction (e.g., [

161]), quality perceptions and performance attributes (e.g., [

161]), implementation of management measures and effects on satisfaction (e.g., [

161]), among others. Regarding tourist and visitor segmentation studies, the majority of the recent studies focused on segmentation based on the motivation of tourists, including the motivation of domestic visitors (e.g., [

162]) and international tourists (e.g., [

163]) and motivations regarding ecotourism (e.g., [

164,

165]). There is also research that addressed segmentation according to tourists’ climate sensitivity and climate change perceptions (e.g., [

166]) and visitors’ place attachment (e.g., [

167]).

3.6.6. Wildlife Tourism

The increasing desire to observe and interact with wildlife is reflected in a substantial increase in visits to PAs from all over the world. The World Travel & Tourism Council [

168] estimates that, globally, 21,8 million jobs are supported by wildlife tourism, and one-third of the GDP generated by tourism in Africa is directly connected to wildlife. In this context, as an NBT subcategory, wildlife tourism in the context of PAs received some attention over the last few years. In recent years, the theme has been frequently centred on the analysis of tourism contributions to the local economy and animal conservation (e.g., [

169]), the improvement in managing and minimising negative impacts (e.g., [

170,

171]), the assessment of cultural ecosystem services (e.g., [

171]), analyses focused on tourists (e.g., [

172]), and the impacts and changes fostered by the COVID-19 pandemic (e.g., [

172,

173,

174]).

4. Discussions and Implications

Although several bibliometric reviews have been conducted in the field of sustainability [

67,

175,

176,

177] or ecotourism [

178], there are still no studies that focus specifically on NBT and PAs. Such investigations are crucial in the context of building resilient territories as they contribute to a comprehensive understanding of the interactions between NBT and PAs. This study presents a comprehensive review of the research related to PAs and NBT over the last 30 years, providing information on the state-of-the-art and identifying trends with the selection and analysis of more relevant scientific articles in this area of research. One of the merits of this work is including all journals available and not excluding or filtering out publications in certain areas of knowledge (e.g., tourism). The scientific publications indexed in WoS (

n = 1033) were obtained from more than 380 sources and were integrated in more than 140 research categories. The three decades under analysis show a lack of research published in the first decade (1991–2000). The increase in the number of publications in WoS on NBT in PAs was almost 500% in comparison to the second decade under analysis. This proves that, on the one hand, researchers have an increasing interest in these themes, and, on the other hand, there is the democratisation of scientific publications as a method for the dissemination of their results. The popularisation of scientific disclosure using articles in scientific journals occurs in several countries, in several areas of knowledge, and in different journals and authors. The scientific journals

Journal of Sustainable Tourism and

Tourism Management are considered the most dynamic and active. Despite the evolution, there is a need for greater cooperation between countries from different continents. International scientific cooperation may contribute to an increase in expertise sharing, research skills, and the development of new studies in the area.

The keywords analysis allowed the identification of five main research themes on PAs and NBT: (1) ecotourism; (2) nature conservation, biodiversity, and sustainability; (3) national parks, recreation, and climate change; (4) sustainable management and development; and (5) with a lesser degree of representation, themes related to China, ecosystem services, and resilience. This contribution is particularly interesting for scholars that aim to obtain a global vision of the research on PAs and NBT.

It is also particularly interesting to understand the presence of different elements of research related to the theme of this paper. The tendency of researchers shows the existence of six research trends over the last years: (1) sustainable tourism; (2) climate change; (3) geotourism and rural tourism; (4) ecosystem services and cultural ecosystem services; (5) visitor studies; and (6) wildlife tourism. The research context focuses on themes related to the tourism sector (e.g., ecotourism), but concerns are also raised with themes that are common to different sectors (e.g., nature conservation, biodiversity and sustainability, and sustainable management and development). The global concerns regarding climate change, ecosystems, and resilience make them a research target for PAs, in particular, for national parks. The research leads us to conclude that there is a need for more research regarding other categories of PAs, and it is equally important to be open to new collaborative networks with African countries, where scientific research is particularly focused on cooperation with South Africa. Another conclusion of this study is the scarcity of studies related to the themes under analysis and the COVID-19 pandemic. This is explained by the fact that this theme has only been introduced in the last 2 of the 30 years under analysis. However, there is a great need to understand the effects of the pandemic on the dynamics between PAs and NBT and which solutions can promote their sustainability and resilience.

Despite the contributions and merits, this paper has limitations. Bibliometric analyses are eminently descriptive and often have a relatively limited deep explanatory ability, and this study is not an exception. Another limitation relates to the fact that only scientific articles written in English and indexed in WoS were selected. Future research should consider other databases and other types of documents (e.g., proceeding papers and books) in different languages. The inclusion of these elements and consequent research extension may contribute to further insights into the analysis of the study area.

Scientific Output Implications

Scientific production generally reflects the knowledge and opinions of researchers regarding a specific research subject. Knowledge production can be conducted by researchers affiliated with institutions within the same territorial context where the study is conducted or in third-party countries. The main challenge we faced when analysing this issue was the existence of a large volume of scientific production originating predominantly from the Northern Hemisphere. This fact leads to a lack of understanding regarding the perspectives of researchers from and affiliated with institutions in the Southern Hemisphere.

This literature review revealed a lack of critical mass in knowledge production by researchers affiliated with institutions in the African continent. While open-access scientific production, celebrated by the Budapest Open Access Initiative, has contributed to the growth of scientific output, we still remain unaware of the realities in many territories. The majority of scientific production indexed in the Web of Science (WoS) platform is associated with researchers from South Africa, leaving a significant gap regarding the remaining countries on the African continent.

Another major divide in discourse regarding nature conservation relates to nature protection models. On the one hand, the American model focuses on conserving nature and wildlife, thus prohibiting anthropogenic activities within PAs. On the other hand, the discourse on nature conservation goes beyond safeguarding nature or the need for protection; it also encompasses the preservation of traditions, local communities, and rural economies. There is a clear duality in the management of PAs, which may be traced back to the establishment of these nature reserves. In the context of the colonial period, colonizing countries displayed a dual approach to nature protection. On the one hand, they maintained a preservationist approach toward protecting natural areas within their national territory, aiming to ensure the continuity of territorial quality, especially since many parks were established on private lands with a long history of human presence. On the other hand, a conservationist perspective was used for colonies or overseas provinces, where the concern for nature conservation was linked to uninhabited landscapes. These purposes continue to influence researchers’ concerns regarding the territories under study, creating distinct discourses.

5. Conclusions

PAs are recognised as territories where the preservation of ecosystems and inhabitants should be the priority. Although tourism is not the main focus of these areas, it should be promoted in a sustainable way and in accordance with the goals of the United Nations Agenda 2030.

From the analysis made on scientific production related to NBT and PAs, it was possible to identify several trends. Climate change is recognised as an influential factor in the tourism sector. It was observed that a significant number of studies focused on understanding its effects on PAs and its impact on visitor behaviour. It was also identified that the concepts of geotourism and rural tourism were often associated with themes such as development, sustainable development, and the relationship between PAs and communities. Ecosystem services, particularly cultural ecosystem services, were of significant importance. Ecosystem services were studied to support nature-based tourism and sustainable management of PAs. There was also frequent reference to the fact that the tourism sector revolves around the tourist.

Visitor studies provide valuable information for sustainable management, encompassing motivations, satisfaction, and segmentation of tourists and visitors. Recent studies have explored the economic contributions of wildlife tourism, conservation efforts, cultural ecosystem services, and the impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic. These findings highlighted the multidimensional nature of research in PAs and nature-based tourism, reflecting a global perspective with contributions from various countries and institutions.