Historic Graffiti as a Visual Medium for the Sustainable Development of the Underground Built Heritage

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. Graffiti in the Underground Built Heritage: Some Preliminary Considerations Based on the U4V Experience

1.2. Historic Graffiti: Two Levels of Addressing Sustainability

1.2.1. Historic Graffiti as a Sustainable Form of Visual Expression

1.2.2. Historic Graffiti as an Agent for Fostering Cultural Heritage Sustainability

2. Underground Graffiti in Context: Two Case Studies

2.1. The Cave Church of Ayia Napa, Cyprus: Research Background

2.1.1. The Site and Its Origin

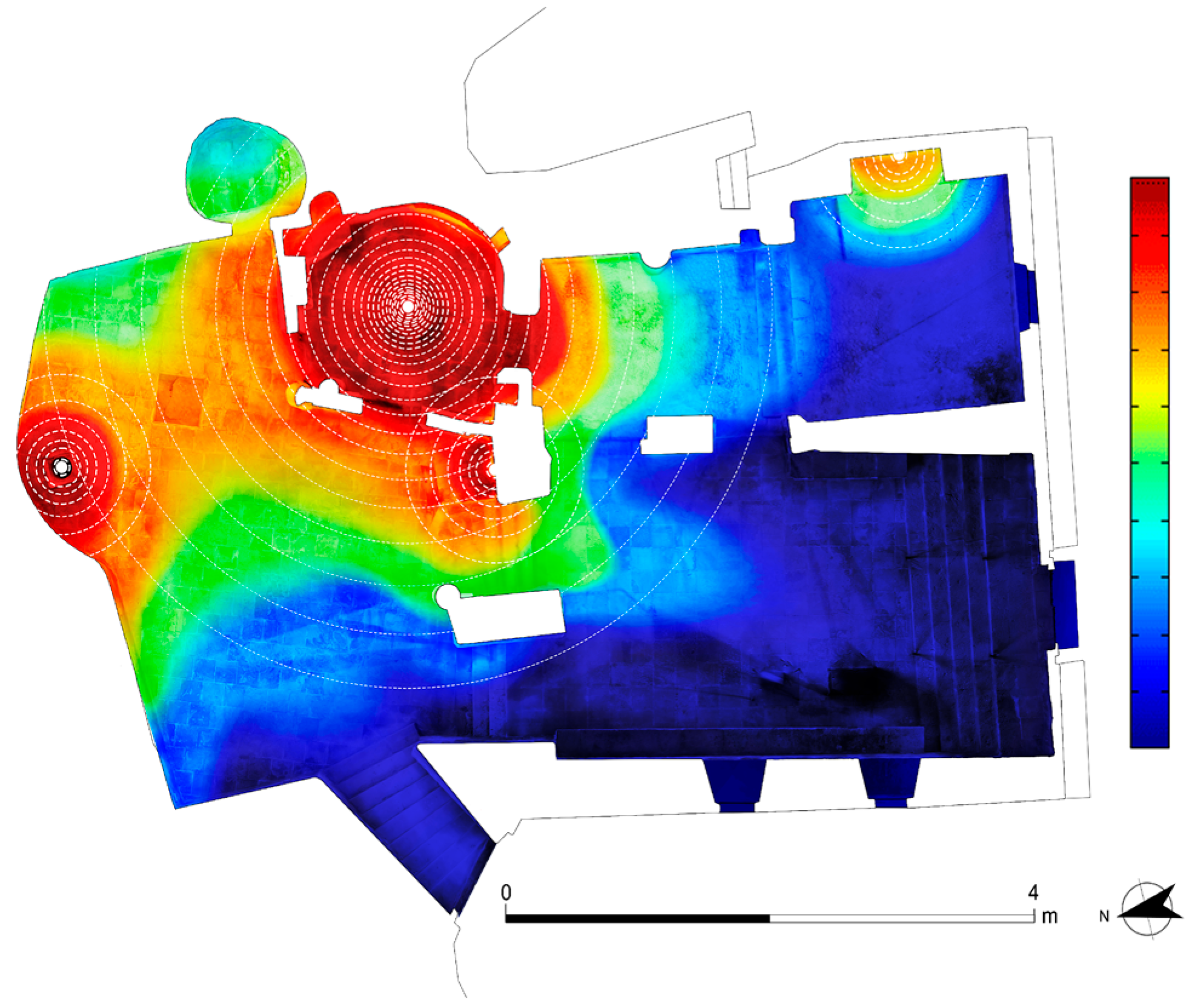

2.1.2. Graffiti in the Church Complex: Spatial Distributions and Types

2.1.3. Graffiti Documentation

2.1.4. Graffiti Interpretation

2.1.5. Graffiti as an Agent for Promoting Sustainability in the UBH of Ayia Napa

2.2. Saint Helena Chapel—Jerusalem: Research Background

- To date the Crosses, that is, to refute or confirm the perception that they are from the time of the Crusaders;

- To consider if the crosses can be categorized as graffiti;

- To decipher the identity of the cross-makers;

- To understand the phenomenon and its functions.

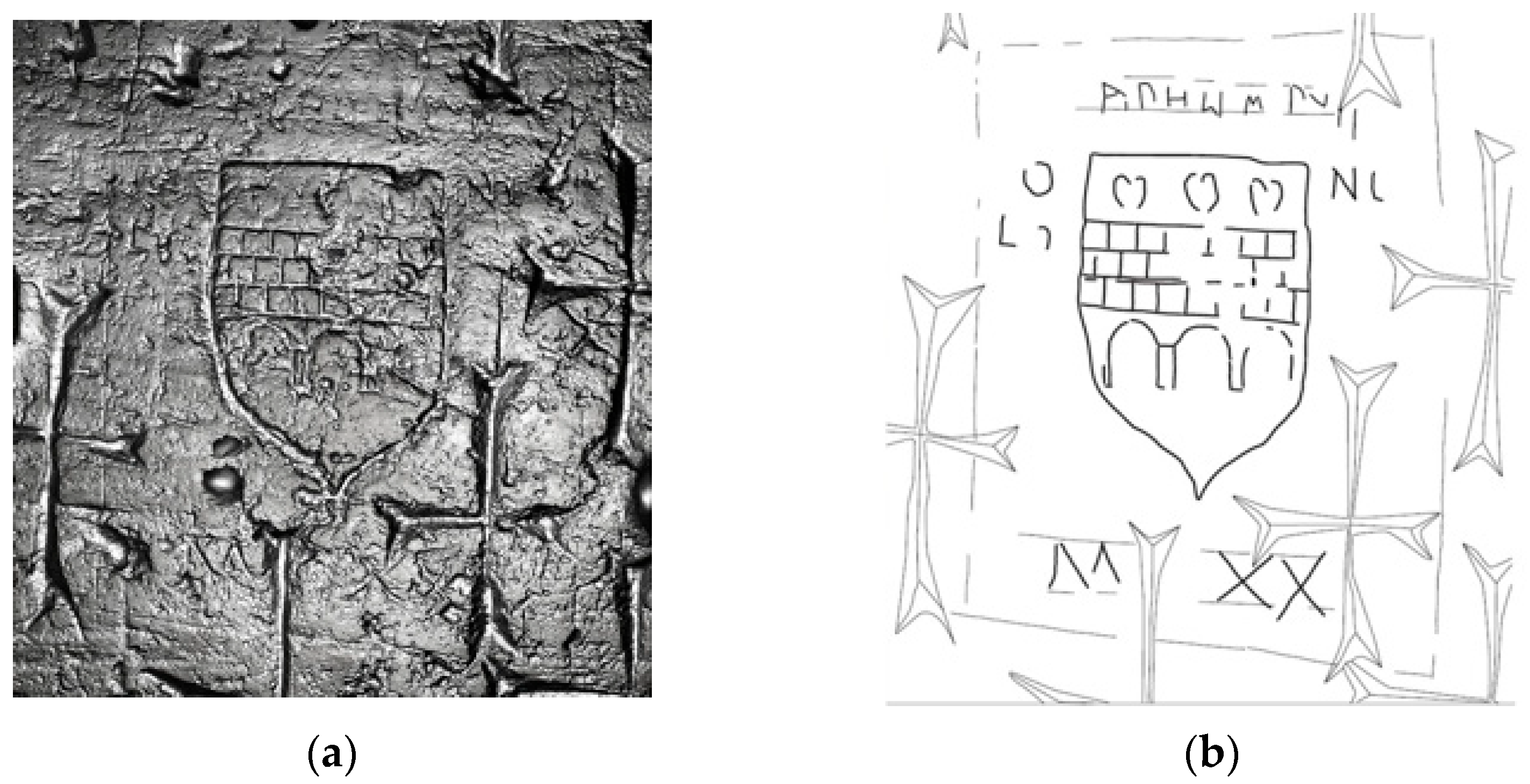

2.2.1. Dating the Crosses

2.2.2. Graffiti or Not

2.2.3. Who Were the Cross-Makers?

2.2.4. Graffiti and Crosses: Interpretation

2.2.5. Graffiti as an Agent for Promoting Sustainability in the UBH of Saint Helena Chapel

3. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

Appendix A.1. How to Approach Graffiti: A Methodological Overview

- The graffiti-making process as a form of visual communication embracing textual and pictorial material and

- The relationship between graffiti and their spatial location as markers of human interaction with the landscape.

Appendix A.2. Graffiti Workflow

Appendix A.3. The Graffiti Making Process: How Form, Content, and Space Combine

Appendix A.4. How Form, Content and Space Combine in Graffiti Analysis and Interpretation: An Example

Appendix A.5. Spatial Analysis and Graffiti Distribution

References

- Lovata, T.R.; Olton, E. Understanding Graffiti: Multidisciplinary Studies from Prehistory to the Present; Routledge: London, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Lohmann, P. Historical Graffiti: The State-of-the-Art. J. Early Mod. Stud. 2020, 9, 37–56. [Google Scholar]

- Langner, M. Antike Graffitizeichnungen. Motive, Gestaltung und Bedeutung. Palilia 11; Reichert Verlag: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Kraack, D.; Lingens, P. Bibliographie zu Historischen Graffiti Zwischen Antike und Moderne; Medium Aevum Quotidianum: Krems, Austria, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Baird, J.; Taylor, C. Ancient Graffiti in Context; Routledge: London, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Turner, V.W. Symbols in African Ritual. Science 1973, 179, 1100–1105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Foote, K.E.; Azaryahu, M. Sense of Place. In International Encyclopedia of Human Geography; Kitchin, R., Thrift, N., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2009; pp. 96–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lo Presti, O.; Carli, M.R. Promoting Underground Cultural Heritage through Sustainable Practices: A Design Thinking and Audience Development Approach. Sustainability 2023, 15, 9125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, K. The social pillar of sustainable development: A literature review and framework for policy analysis. Sustain. Sci. Pract. Policy 2012, 8, 15–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- European Commission. Directorate-General for Education, Youth, Sport and Culture, Sustainable Cultural Tourism; Publications Office: Luxembourg, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duxbury, N.; Bakas, F.E.; Vinagre de Castro, T.; Silva, S. Creative Tourism Development Models towards Sustainable and Regenerative Tourism. Sustainability 2021, 13, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demesticha, S.; Delouca, K.; Trentin, M.G.; Bakirtzis, N.; Neophytou, A. Seamen on Land? A Preliminary Analysis of Medieval Ship Graffiti on Cyprus. Int. J. Naut. Archaeol. 2017, 46, 346–381. [Google Scholar]

- Champion, M.J. The Priest, the Prostitute, and the Slander on the Walls: Shifting Perceptions towards Historic Graffiti. Peregrinations J. Mediev. Art Archit. 2017, 6, 5–37. Available online: https://digital.kenyon.edu/perejournal/vol6/iss1/20 (accessed on 23 July 2023).

- Avramidis, K.; Tsilimpounidi, M. Graffiti and Street Art; Routledge: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Ross, J.I. Routledge Handbook of Graffiti and Street Art; Routledge: London, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Vanderveen, G.; Van Eijk, G. Criminal but Beautiful: A Study on Graffiti and the Role of Value Judgments and Context in Perceiving Disorder. Eur. J. Crim. Policy Res. 2016, 22, 107–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Keramati Ardakani, M.; Ahmadi Oloonabadi, S.S. Collective memory as an efficient agent in sustainable urban conservation. Procedia Eng. 2011, 21, 985–988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bacci, M. Mixed shrines in the Late Byzantine period, in Archaeologia Abrahamica. In Studies in Archaeology and Artistic Tradition of Judaism, Christianity and Islam; Beljaev, L.A., Ed.; Russian Academy of Sciences, Institute of Archaeology/ Indrik: Moscow, Russia, 2009; pp. 433–444. [Google Scholar]

- Trentin, M.G.; Vico, L. The case study of Ayia Napa Monastery. In Practices for the Underground Built Heritage Valorisation. Second Handbook; Martinez-Rodriguez, S., Pace, G., Eds.; CNR: Naples, Italy, 2023; pp. 33–42. [Google Scholar]

- Hadjisavvas, S. New light on the history of the Ayia Napa region. In Report of the Department of Antiquities of Cyprus; Department of Antiquities of Cyprus: Nicosia, Cyprus, 1983; pp. 315–318. [Google Scholar]

- Μιτσίδι, A. [Mitzidi, A.] H μονή τησ Άγιας Νάπας, Aπόστολος Βαρνάβα; [Apostolos Barnàva] Nicosia, Cyprus. 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Re’em, A.; Caine, M.; Altaratz, D.; Tchekhanovets, Y. Historical Archaeology of Medieval Pilgrimage: Dating the “Walls of the Crosses” in the Holy Sepulchre Chapel of St. Helena. NSAJR 2022, 15, 7–45. [Google Scholar]

- Friedman, Y. Pilgrims in the Shadow of the Crusader Kingdom. In Knights of the Holy Land, The Crusader Kingdom of Jerusalem; Rozenberg, S., Ed.; The Israel Museum: Jerusalem, Israel, 1999; pp. 100–110. [Google Scholar]

- Krüger, J. Die Grabeskirche zu Jerusalem: Geschichte, Gestalt, Bedeutung; Schnell & Steiner: Regensburg, Germany, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Tyerman, C. The World of the Crusades; Yale University Press: New Haven, CT, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Caine, M.; Altaratz, D.; MacDonald, L.; Re’em, A. The Riddle of the Crosses: The Crusaders in the Holy Sepulchre. In Proceedings of the Electronic Visualisation and the Arts (EVA) Conference, 9–13 July 2018; pp. 132–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ulvi, A.; Yakar, M.; Yiğit, A.; Kaya, Y. The use of photogrammetric techniques in documenting cultural heritage: The Example of Aksaray Selime Sultan Tomb. Univers. J. Eng. Sci. 2019, 7, 64–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Skarlatos, D.; Kiparissi, S. Comparison of laser scanning, photogrammetry and SFM-MVS pipeline applied in structures and artificial surfaces. ISPRS Ann. Photogramm. Remote Sens. Spatial Inf. Sci. 2012, I-3, 299–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kraack, D. Monumentale Zeugnisse der spätmittelalterlichen Adelsreise: Inschriften und Graffiti des 14.-16. Jahrhunderts; Vandenhoeck und Ruprecht: Göttingen, Germany, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Pringle, D. The Churches of the Crusader Kingdom of Jerusalem: A Corpus III: The City of Jerusalem; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Grigoryan, G. On the Interpretation of the Crosses Carved on the External Walls of the Armenian Church in Famagusta. In The Armenian Church of Famagusta and the Complexity of Cypriot Heritage (Mediterranean Perspectives); Walsh, M.J.K., Ed.; Palgrave Macmillan: New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Fabri, F. The Wandering of Brother Felix Fabri; Stewart, A., Ed.; and Translator; Palestine Pilgrims’: London, UK, 1896–1897; pp. 7–10.

- ALLEA Report 2020 Sustainable and FAIR Data Sharing in the Humanities. Available online: https://www.ria.ie/sites/default/files/allea_sustainable_and_fair_data_sharing_in_the_humanities_2020_0.pdf (accessed on 23 July 2023).

- Trentin, M.G.; Felicetti, A. Between Written and Visual Communication: CIDOC CRM Ontology for Medieval and Early Modern European Graffiti. J. Comput. Cult. Herit. 2023. [CrossRef]

- Ragazzoli, C.; Harmanşah, Ö.; Salvador, C.; Frood, E. Scribbling through History: Graffiti, Places and People from Antiquity to Modernity; Bloomsbury Academic: London, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Trentin, M.G. Form, Content and Space. Methodological Challenges in the Study of Medieval and Modern European Graffiti. Pap. Inst. Archaeol. PIA 2021, 31, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plesch, V. Memory on the wall: Graffiti on religious wall paintings. J. Mediev. Early Mod. Stud. 2002, 32, 167–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plesch, V. Destruction or Preservation? The Meaning of Graffiti at Religious Sites. In Art, Piety and Destruction in European Religion, 1500–1700; Raguin, V., Ed.; Ashgate: Aldershot, UK, 2010; pp. 137–172. [Google Scholar]

- Yasin, A. Prayers on Site: The Materiality of Devotional Graffiti and the Production of Early Christian Sacred Space. In Viewing Inscriptions in the Late Antique and Medieval World; Eastmond, A., Ed.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2015; pp. 36–60. [Google Scholar]

- Van Belle, J.L.; Brun, A.S. Le Graffiti-Signature: Reflet D’histoire; Éditions Safran: Bruxelles, Belgium, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Trentin, M.G. Medieval and Modern Graffiti: Multicultural and multimodal communication in Cyprus. Cah. Du Cent. D’etudes Chypr. 2021, 50, 277–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schryver, J.G.; Schabel, C.D. The Graffiti in the ‘Royal Chapel’ of Pyrga. In Report of the Department of Antiquities of Cyprus; Departmentc of Antiquities of Cyprus: Nicosia, Cyprus, 2003; pp. 327–334. [Google Scholar]

- Hani, J. Il Simbolismo del Tempio Cristiano; Edizioni Arkeios: Rome, Italy, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Mascardi, V.; Deufemia, V.; Malafronte, D.; Ricciarelli, A.; Bianchi, N.; De Lumey, H. Rock art interpretation within indiana MAS. In Proceedings of the 6th KES International Conference on Agent and Multi-Agent Systems: Technologies and Applications (KES-AMSTA’12), Dubrovnik, Croatia, 25–27 June 2012; pp. 271–281. [Google Scholar]

- Dell’Unto, N.; Landeschi, G. Archaeological 3D GIS; Taylor & Francis: Routledge, Germany, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual authors and contributors and not of MDPI and/or the editors. MDPI and/or the editors disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Trentin, M.G.; Altaratz, D.; Caine, M.; Re’em, A.; Tinazzo, A.; Gasanova, S. Historic Graffiti as a Visual Medium for the Sustainable Development of the Underground Built Heritage. Sustainability 2023, 15, 11697. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151511697

Trentin MG, Altaratz D, Caine M, Re’em A, Tinazzo A, Gasanova S. Historic Graffiti as a Visual Medium for the Sustainable Development of the Underground Built Heritage. Sustainability. 2023; 15(15):11697. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151511697

Chicago/Turabian StyleTrentin, Mia Gaia, Doron Altaratz, Moshe Caine, Amit Re’em, Andrea Tinazzo, and Svetlana Gasanova. 2023. "Historic Graffiti as a Visual Medium for the Sustainable Development of the Underground Built Heritage" Sustainability 15, no. 15: 11697. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151511697

APA StyleTrentin, M. G., Altaratz, D., Caine, M., Re’em, A., Tinazzo, A., & Gasanova, S. (2023). Historic Graffiti as a Visual Medium for the Sustainable Development of the Underground Built Heritage. Sustainability, 15(15), 11697. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151511697