1. Introduction

Social prescribing initiatives are personalized coaching initiatives designed to help participants better cope with their personal situations and, as a result, lower their need for medical and social services [

1]. Healthcare professionals can facilitate patients’ access to a variety of community-based non-clinical services to enhance their health and well-being through social prescribing [

2,

3]. The precise “social prescriptions” are unique to each community and care environment, but they often include programs promoting physical exercise and artistic expression as well as mental health support, social inclusion, financial guidance, and housing advice [

4,

5]. Through social prescribing, people can access non-medical assistance for coping with these problems and other unmet requirements [

5].

The social prescribing movement has rapidly expanded in the past few years, leading the health and non-profit sectors from many countries to adopt a variety of concepts, procedures, and methodologies [

6,

7,

8]. Even though social prescribing can take various paths, the most widely used model benefits highly from the involvement of link workers, who are specialized in identifying the individual needs of the patient. Ideally, the link workers follow the patient’s progress and build up a team with the healthcare provider in the form of the general practitioner or healthcare facility [

2]. According to Husk, “social prescribing” refers to the patient’s journey from primary care to whatever activity is conducted [

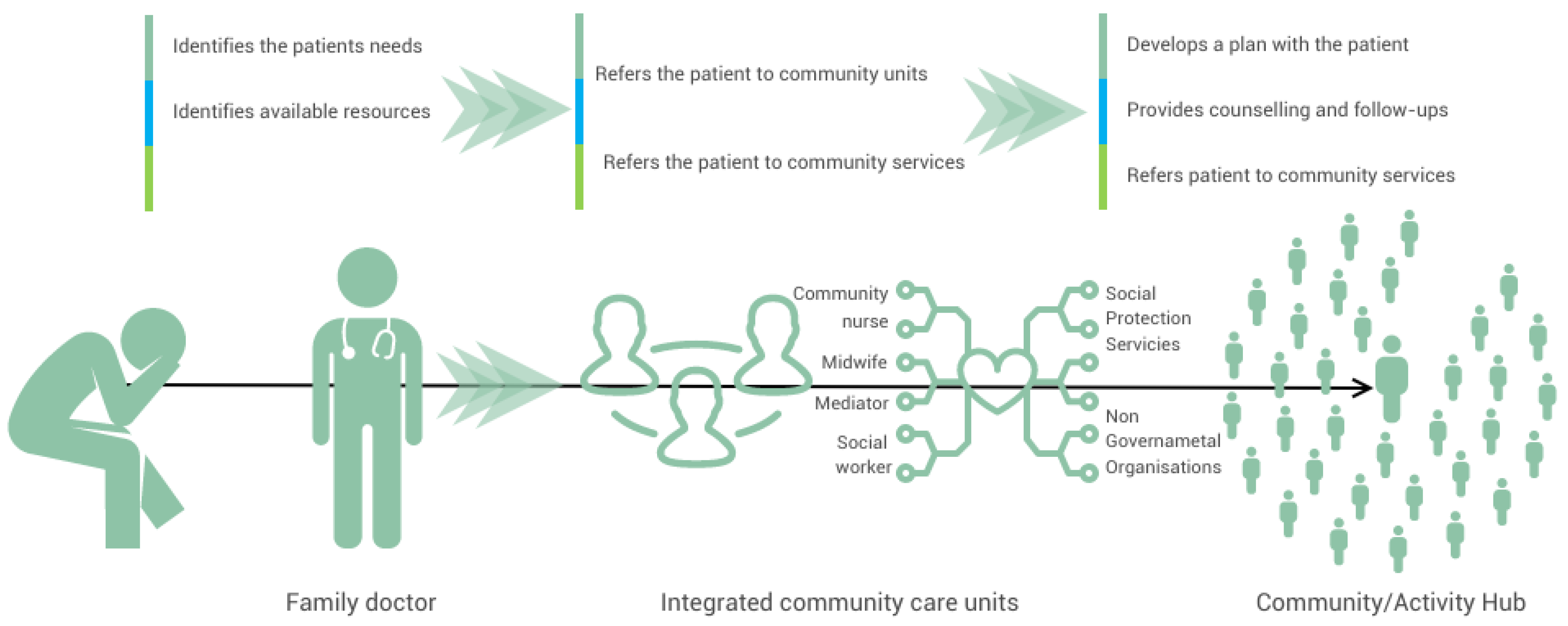

9]. Based on that, we have provided a simplified representation of the possible pathways that might be involved in it (

Figure 1).

One of the most common activities recommended in social prescribing is group exercise or physical activity, with beneficial results in patients with chronic pain [

10], disability [

11], dementia [

12], and mental health problems [

13,

14]. People with a variety of health and social issues can benefit from gardens and gardening in terms of their health and well-being. Globally, the advantages of gardening could be used as a “social prescription” for individuals with chronic illnesses [

15] as well as ease some health challenges that humanity is currently confronting [

16].

Additionally, other social prescribing interventions have been proven to have a positive influence on health outcomes. For example, music therapy has shown significant positive effects on the emotional well-being, social engagement, and overall psycho-social well-being of individuals with dementia, particularly those with moderate dementia. Studies have highlighted the benefits of music intervention in alleviating depression and anxiety in this population. Through singing, music therapy interventions have demonstrated improvements in feelings, emotions, and social interaction. Specifically, weekly short interventions lasting more than 45 min were found to be effective in regulating emotions [

17].

However, the implementation of music therapy as a social prescription faces challenges such as the formalization of the social prescribing process, securing buy-ins from healthcare professionals, sustainable funding, and institutional knowledge retention [

18]. One review identified several barriers to the broader integration of singing on prescription, including the lack of formalization in the social prescribing process, challenges in securing support from general practitioners and healthcare professionals, difficulties in sustaining funding, and organizational changes leading to staff turnover and the loss of institutional knowledge [

19].

In the face of the increasing the burden of chronic diseases, low levels of prevention, and rising healthcare costs, the identification of innovative solutions, including those beyond the healthcare system, is imperative. According to the Eurostat database, the per capita health cost in Romania was the second lowest in the European Union [

20] in 2015. Further investigations have revealed that our country had an average of USD 830 in health spending per person in 2019, with a projection for this figure to increase up to USD 1040 by 2026 [

21]. Since the majority of the costs comes from the public health system, vulnerable groups (the unemployed Roma population and pensionaries) and overall rural populations with lower accessibility to medical services face unmet medical needs [

22], making social prescribing initiatives a promising approach to building a sustainable healthcare system, emphasizing prevention, and leveraging other complementary resources and interventions.

Given the lack of research at the national level and the emerging body of evidence brought by international research on the benefits of social prescribing, especially on long-term sustainable healthcare, an analysis of the opportunities for social prescribing is necessary.

1.1. Methodology

We performed a scoping review with the aim of unveiling opportunities for social prescribing and its value in unburdening healthcare and offering sustainability. As per definition, scoping reviews are useful for identifying and mapping the available evidence and for examining emerging evidence when no precise research questions can be posed yet, and they can report on different types of evidence to inform the practice in the field [

23]. The analysis was carried out based on the country’s context, where the link between healthcare and the alternative interventions offered by social prescribing is not formally recognized. Our research question referred to the population having or not having a chronic disease (population) and being in chronic care management or in preventative care (concept), especially at the level of primary care but also at other levels of care (context).

We performed searches not only in databases such as PubMed and Medline but also by using the gray literature. The search words were “social prescribing”, “chronic care”, “preventive care”, “burden of care”, “sustainability”, “primary care”, “vulnerable populations”, “social services”, and “link workers”.

We retrieved quantitative and qualitative studies. The thematic analysis was developed through team discussions.

Since national research is scarce in this field, we also reviewed governmental and non-governmental reports, statistical databases, regulatory frameworks, and policy documents. We also looked at successful models of social prescribing in other countries.

1.2. The Healthcare System—Structure and Potential Role in Social Prescribing

The healthcare system in Romania comprises various medical structures, public and private organizations, and resources aimed at preventing, maintaining, improving, and restoring the health of the population. The Ministry of Health and its specialized structures have a responsibility to coordinate the public healthcare system at the national and territorial levels.

Primary healthcare is the initial point of contact for individuals, providing comprehensive care encompassing the physical, psychological, and social aspects of health, and it has a privileged position to benefit from social prescribing. It focuses on prevention, health promotion, acute and chronic care, home care, and community-based medical services.

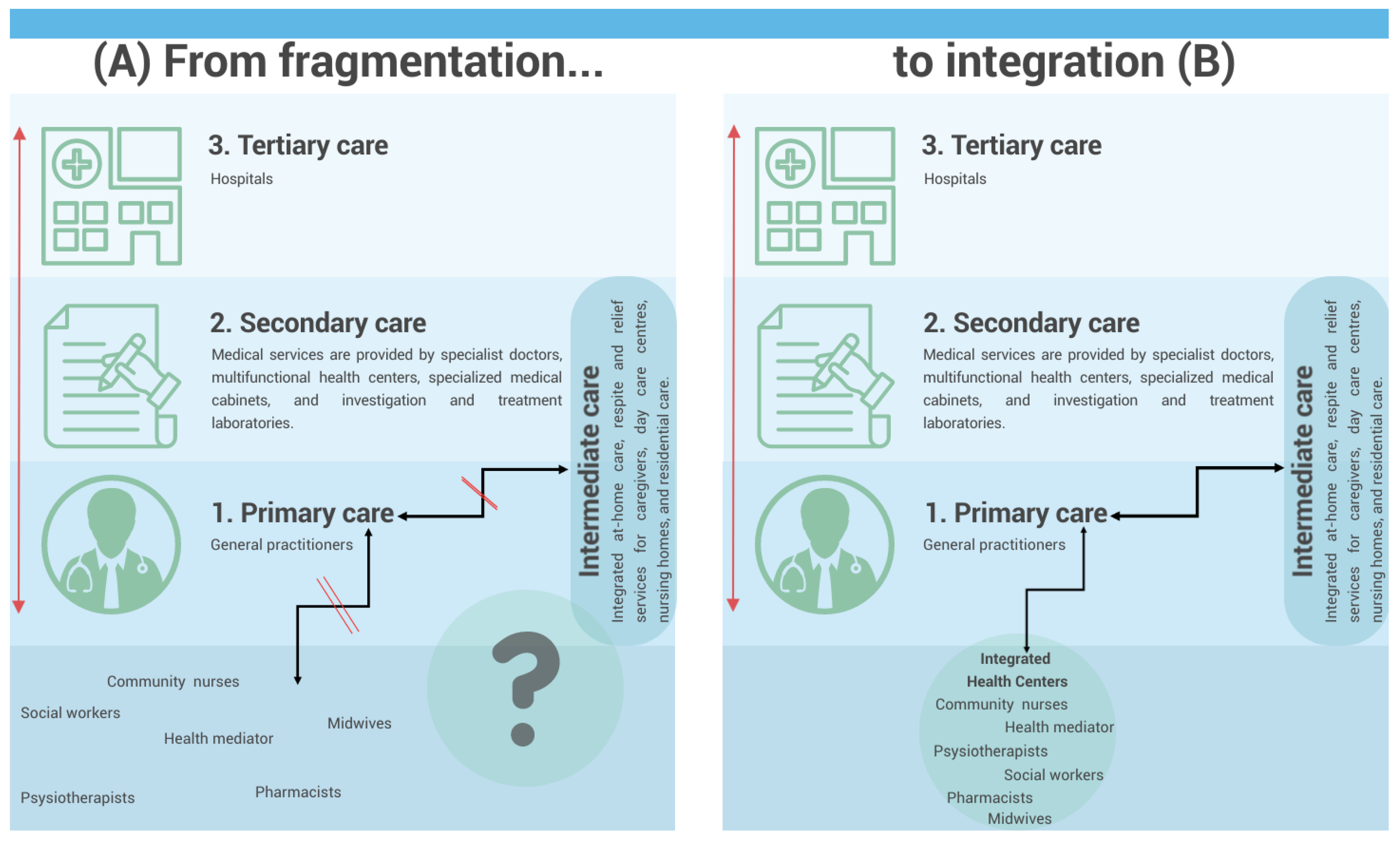

In Romania, primary healthcare is assimilated to general practitioners (GPs), named family doctors. Community healthcare workers (

Figure 2) are a distinct part of the system, but they should cooperate with family doctors, especially in rural areas. They work independently, coordinated by the county health authorities, but no integration with primary care was established until recently when the Ministry of Health launched a call for integrated community centers aimed at collaboration between primary care physicians; public social assistance services; and other healthcare, social, and educational service providers, including non-governmental organizations specialized in these fields [

24]. To illustrate the fragmentation of care, we have drawn

Figure 2A, a schematic representation of the Romanian healthcare system, emphasizing an important aspect: a significant part of the system, including community healthcare workers, midwives, healthcare mediators, pharmacists, psychotherapists, and social workers, currently lacks a clear connection with primary care and family doctors (general practitioners, GPs). This fragmentation hinders the effective implementation of social prescribing initiatives.

The perspective of future Integrated community centers is to play a pivotal role in addressing this issue. These centers can serve as a means of integrating all these healthcare actors, who are currently not adequately connected to primary care. By establishing direct links with family doctors, these centers can bridge the gap and create a collaborative environment that fosters effective social prescribing practices (

Figure 2B).

By operating within communities, community health centers are well-positioned to understand the unique needs and challenges faced by vulnerable groups. Through collaboration with various stakeholders, including healthcare providers, social services, and educational institutions, these units can identify appropriate social prescribing initiatives that address the specific needs of individuals. By prescribing social interventions and support services alongside medical treatment, integrated community health centers can contribute to holistic and comprehensive care for vulnerable populations, promoting better health outcomes and overall well-being [

25].

Another level of integration with primary care could be intermediate care units. Intermediate care units aim to provide integrated at-home care, respite and relief services for caregivers, day care centers, nursing homes, and residential care [

26]. For patients with special needs, intermediate care units bridge the gap between primary and secondary care (

Figure 2).

2. Available Social Services

Various governmental and non-governmental organizations (NGOs) have been instrumental in providing essential services to vulnerable groups. Notably, day centers for the elderly, managed by social protection services or NGOs, have been established to address the unique needs of this demographic.

These day centers have multiple objectives, including maintaining or improving their mental and sensory capacity, preventing health deterioration, and promoting overall well-being. To achieve these objectives, a range of services are offered within the centers. Information activities and social counseling play a crucial role in understanding the beneficiaries’ situations and providing appropriate support. Additionally, primary healthcare services monitor the functional parameters, ensuring the well-being of the elderly. Psychological counseling services cater to their mental and emotional well-being [

27,

28].

Furthermore, functional recovery and rehabilitation services are provided to enhance their physical capabilities and promote independent living. Social integration and reintegration activities, skill-building exercises, socialization, and leisure activities all foster a sense of community and engagement. Adequate support is provided by ensuring the provision of breakfast and lunch, while proper hygiene conditions and restful environments are maintained to ensure the well-being and comfort of the elderly [

29].

Through these organized services and support systems, Romania strives to ensure the availability of necessary resources, easy accessibility to services, and the continuity of care for vulnerable groups. By addressing the unique needs of children at risk and the elderly, these initiatives contribute to creating a more inclusive and supportive society for all individuals in Romania.

Respite centers for the elderly offer temporary accommodation for a limited period (up to 180 days per calendar year). They provide elderly individuals, who have reached the retirement age defined by the law and do not require specialized medical assistance, with suitable housing, food, primary medical care, recovery and rehabilitation services, leisure activities, and social assistance. Such centers cater to those whose legal guardians are unable to provide home care due to valid reasons and to those who are in the situation where no suitable home care services are available in the community [

29].

Day centers for children and young people in Romania serve diverse purposes tailored to their specific needs, encompassing day care centers for children at risk of separation from their parents, day rehabilitation centers for children with disabilities, and day centers offering counseling and support for parents and children. These centers play a crucial role in providing supervision, counseling, and emotional support to promote the well-being and overall development of children and young individuals who require assistance [

27].

Hospice day care centers offer support and care for children and adults facing palliative care needs. These centers provide a range of services, including socio-recreational activities, occupational therapy, psycho-educational intervention through the hospice’s school, psychological counseling, social and spiritual support, physical therapy, and primary healthcare. By engaging individuals in creative activities and fostering a supportive environment, these centers contribute to the well-being and quality of life of the patients and their families [

30].

Day centers for alcoholics or drug addicts play a crucial role in the recovery process, combining rehabilitation from addiction with the constructive use of free time. Occupational therapy and art therapy workshops, led by experienced volunteers, are conducted periodically. These workshops engage participants in various creative activities, such as painting, drawing, ceramics, and crafts, which also serve as fundraising initiatives for the centers’ activities [

31].

3. Navigating Policy Structures and Governance in Romania’s Medical and Social Care System

Under the umbrella of policy structures, Romania has implemented initiatives to enhance social services and care for vulnerable groups. The National Recovery and Resilience Plan (PNRR) 2022 is set to play a pivotal role in this regard. As part of the PNRR, a significant step was taken with the planned launch of a call for the creation of a network of day care centers specifically designed to support children at risk of separation from their families. This initiative, scheduled for September 2022, aims to provide vital support and to prevent the separation of vulnerable children from their families [

24].

Furthermore, the development of the Map of Social Services in Romania by an NGO has transformed the visibility of social assistance in the country. Serving as a comprehensive national data platform, the map centralizes and integrates information on accredited social services, categorizing them according to the specific needs of each vulnerable group. This interactive map acts as a valuable resource for individuals, organizations, and authorities to identify and access the appropriate social services across Romania [

32]. Social prescribing programs can be effectively implemented and made sustainable by leveraging existing resources and knowledge, such as digital platforms, mobile applications, and data analytics, that can help identify and refer individuals to the appropriate social prescribing activities.

Based on the existing community relationships surrounding schools and current practices, it is important not to overlook the development of a set of social services that can be offered to children whose parents are temporarily working abroad. These services should be built upon the role of the school within the community and may include specialized counseling (enhancing the role of school counselors), assistance in the learning process, opportunities for shared leisure activities with other children, and home visits [

33]. Some of the identified resources to address this problem in Romania include counseling and guidance provided either by social workers at home or within the local council at the “Child and Family Counseling Service”. Additionally, there are “day center” services that can be accessed for various reasons, such as a lack of time or money for a legal representative or an inability to assist with homework and the learning process of the children [

34].

4. Specific Populations and the Need for Social Prescribing in Romania

To obtain a comprehensive overview of the Romanian population and the general population’s needs, we explored the demographic information provided by the National Institute of Statistics. According to a survey by the Romanian Institute of Statistics, a significant number of households struggle to pay for necessities (24.5%), which frequently results in arrears. The hardest situations in terms of a timely payment capacity affect unemployed people (65.2%) and households with children, especially those with several dependent children (34.8%). Those who are 65 years of age and older, as well as households headed by women, frequently experience these financial difficulties [

35].

Furthermore, another focus of the survey was access to specialized care. The main conclusions underscore the financial obstacles that people encounter in receiving specialized medical treatment, with more than half of them attributing this difficulty to their financial condition. Additionally, factors such as waiting lists, the expectation of self-resolution, fear, and transportation challenges contribute to difficulty in accessing specialist care. People with lower educational levels and those living in rural regions experience these problems more severely [

36].

In Europe, Romania struggles with one of the lowest life expectancy rates, and, unfortunately, the COVID-19 pandemic has set back the progress made since 2000 [

20]. Romania also faces challenges related to preventable mortality, with a higher rate of death from cardiovascular disease, lung cancer, and alcohol-related causes [

20]. Additionally, the mortality from treatable conditions, such as prostate, colorectal, and breast cancers, is alarmingly high, exceeding the EU average [

20].

Low health literacy has been recognized as a significant factor impacting health outcomes [

36]. It can be effectively addressed through social prescription interventions. This is particularly important in rural and Romani communities, where the involvement of trained healthcare mediators, also known as link workers, specialized in communication with Romani populations can greatly enhance the health outcomes of the population. Research is scarce in this area due to numerous difficulties. Various barriers have been identified in conducting research in the rural areas of Romania. These barriers include isolation and a lack of local human resources, such as limited facilities, limited access to medical services, and geographical isolation. Additionally, poor networking between colleagues and a lack of critical mass interest in rural healthcare research hinder the development of supportive networks. A lack of interest from academia, difficulty in engaging future researchers, and the stigma associated with rural researchers’ qualifications and skills further impede research efforts [

37].

The issue of emigration is particularly important for Romania because of its steadily growing scope and the cumulative demographic, social, economic, and political implications that are becoming increasingly problematic [

38]. A recent review highlights the factors that influenced the migration process in Romania between 2000 and 2020 [

38]. The authors identify as the main causes in the field of labor migration the disparities between the standard of living, labor market disparities, the impossibility of young people pursuing a carrier and finding a job, bad governance, and corruption. Migration has altered family solidarity, creating what is referred to as trans-national families, which are households where at least one parent works abroad [

39]. Children from families with international or cross-border ties face a series of challenges, from interpersonal relationships with colleagues and meeting pedagogical requirements, school absenteeism and indiscipline, conflicts with colleagues, and a tendency towards marginalization [

40].

Another important aspect to take into consideration in Romania is women’s needs. Currently, the Gender Equality Index places Romania 26th in the European Union (EU), with the country being 13.5 points lower than the EU’s average score [

41]. Additionally, data from the National Institute of Statistics reveal that households facing difficulty or significant difficulty with their current expenses are those led by women (46.1%) or individuals aged 65 and above (43.3%) [

35].

Other challenges that have emerged in recent years include the upsurge in immigration; the escalating healthcare and pension insurance costs; and the growing demand for affordable care for children, individuals with disabilities, and the elderly. Among those who remain marginalized are people with disabilities, immigrants, ethnic minorities (including Romani people), the homeless, inmates, individuals struggling with addiction, and isolated older adults. These concerns form the core focus of social inclusion efforts [

42].

Sustainability of Social Prescribing Initiatives

According to studies, patients are more likely to enroll if they think the social prescription will be helpful, the recommendation is presented in a way that is acceptable and meets their needs and expectations, and the referrer effectively elicits and addresses their concerns. If the activity is both accessible and transit to the initial session is provided, patients are more likely to participate [

9].

One of the first studies to investigate the factors that influence patients’ willingness to enroll assessed that the most important factors were the patient–provider connection and illness perception. This was followed by motivation, which was the most crucial patient component in the decision to offer self-management help as well as in the belief that it would be successful. Decisions were only minimally influenced by other variables, such as sadness or anxiety, education level, self-efficacy, and social support, whereas age had a somewhat negligible effect as well as disease, disease severity, and the knowledge of disease [

43]. Enrolment rates can be impacted by elements such as participants’ opinions of the program’s worth, the knowledge of social prescribing, and faith in the healthcare system. Patients’ acceptance of treatment may also be influenced by the caliber of the information given to them and the extent of their decision-making freedom as well as the customization of social prescribing interventions to fit their individual preferences, interests, and cultural backgrounds [

44].

Enrolment rates can be considerably impacted by a healthcare provider’s ability to identify and refer patients to social prescribing programs. Enrolment can be affected by variables like awareness, understanding, and the knowledge of social prescribing as well as communication and cooperation between healthcare practitioners and social prescribing link workers [

45].

Engagement describes people’s willingness to actively participate in social prescribing initiatives. It involves connecting people with community-based resources or activities found during the enrollment phase. Engagement can be influenced by the person’s innate drive and perceived need for social prescribing interventions. Engagement can be increased by elements such as a desire for social interaction, an openness to trying new things, and an awareness of the possible advantages [

46]. Engagement can be increased by tailoring social prescribing treatments to suit individual preferences, interests, and cultural backgrounds. Engagement levels can be raised by considering individual circumstances and accessibility issues and by offering options that are in line with the person’s goals [

47].

Several studies have focused on the influence of perceived safety and the level of local crime in moderating the effects of the physical environment and crime on physical activity. People were less likely to participate in activities if public transportation was required, there was a higher rate of neighborhood violence, there was traffic, or there were poorly maintained streets or lighting [

48,

49,

50]. Moreover, the cost of the activity or needed supplies, distance, and ease of access were also noted as factors that interfere with patients’ willingness to attend [

51].

Lastly, the adherence to the activity needs to be considered. Adherence describes how well people regularly engage with and carry out social prescribing initiatives over time. Adherence can be improved by developing trusting connections between patients and community navigators or social prescribing link workers. Adherence rates can be influenced favorably by continued assistance, trust, and regular communication [

52,

53]. Elements like resource accessibility, the ease of participation in activities, and scheduling flexibility might affect adherence. Eliminating obstacles like transportation problems, financial limitations, and time restraints can make it easier for people to follow through with the recommended actions [

54].

5. Discussion

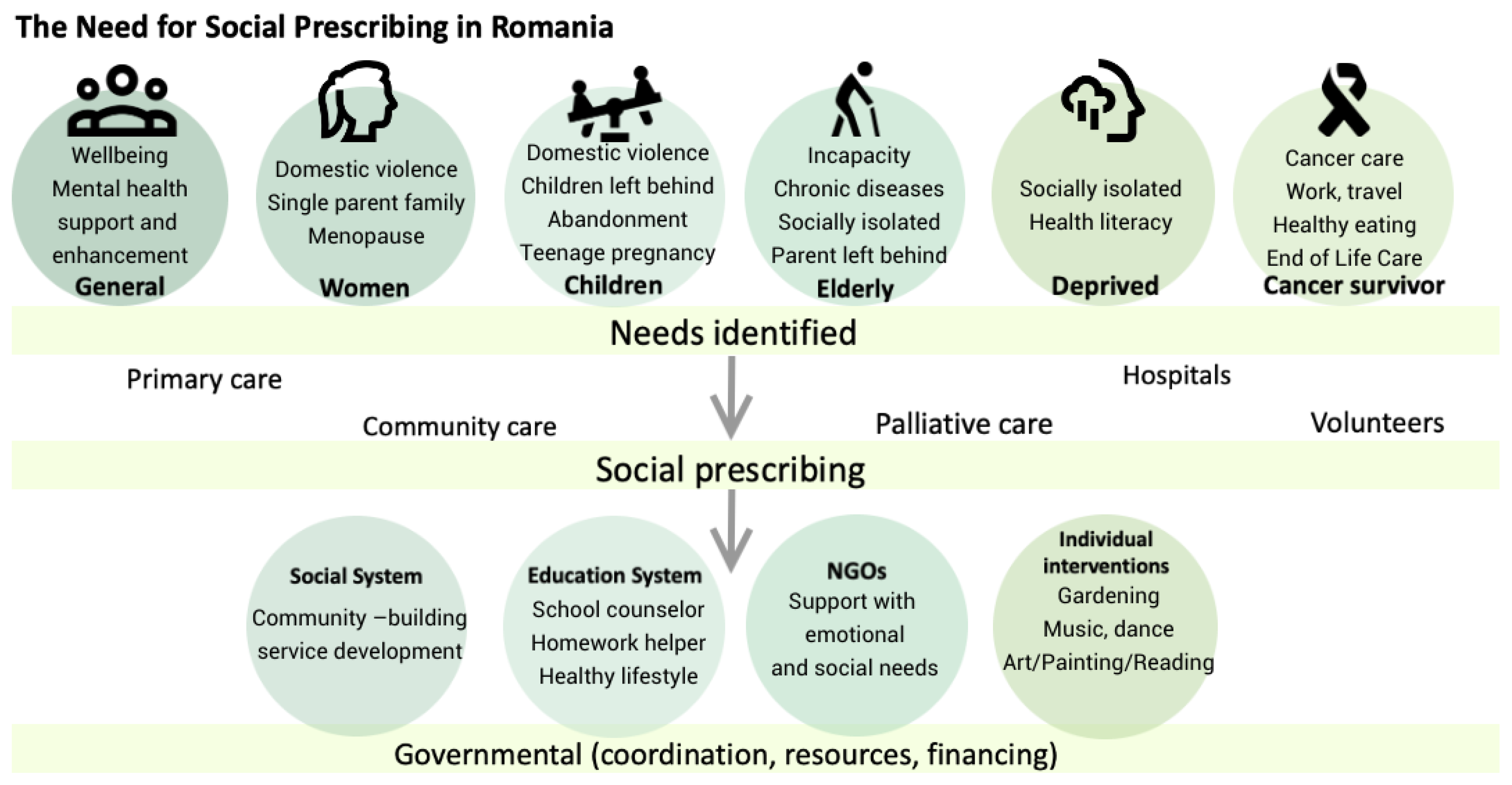

This paper shows that Romania has a social system with important governmental and non-governmental involvement, where health professionals can refer patients from various vulnerable categories to benefit from support either in the community or at home. Social services are dedicated to people with special needs, such as foster children; victims of family violence; immigrants; and deprived populations, including Romani people and the elderly (

Figure 3).

From our analysis, we found that neither governmental documents nor health regulations mention how to connect the two systems or how to enhance the benefits to health of non-medical interventions as proven in the literature.

Although the WHO identifies link workers as the ideal partners of healthcare providers in the journey of social prescription, the only existing and recognized link workers in Romania are sanitary mediators, who have the role of facilitating access to care for Romani populations and access to various health and social services.

Social prescribing can occur at any level of healthcare as is shown in

Figure 3, but, as mentioned by the authors of a review on social prescribing [

55], primary care doctors have a privileged position to recognize social prescription needs due to the long relationship with and holistic approach to the patient.

The UK case study on social prescription in primary care is a model one, with it being part of an NHS initiative (NHS Long-Term Plan 2019), and it is to be followed [

56]. Social prescribing is also the focus of attention of other countries such as North America, Australia, and Scandinavia, the premise being that influencing socio-economic factors has a more recognized impact on health than healthcare [

57].

Therefore, in Romania, we should also invest in empowering primary care providers in social prescribing by informing them better on the benefits and opportunities of social prescribing and facilitating referral through liaison workers such as sanitary mediators, community nurses, and social workers as well as volunteers.

We have also shed light on the development of integrated community centers, which present a valuable opportunity to enhance collaboration between primary care and social services [

24].

Social prescribing is an important tool not only for vulnerable groups but also for the general population in the effort to improve prevention. Individuals can engage in proactive efforts to maintain their well-being and prevent the onset of health difficulties by incorporating hobbies such as gardening, socializing, and religious practices into social prescribing programs.

Addressing the social determinants of health and promoting healthy behaviors are not only attributes of the governmental sector but also those of the private, non-governmental, and even individual and family levels. To ensure the long-term sustainability of social prescribing efforts, there must be integrated applicable policy frameworks, aligned with community development strategies, and efforts aimed at resolving social inequities and individual needs.

It is an emerging approach that has a great potential to improve the well-being and overall health outcomes of individuals [

57]. Even if various NGOs are offering sport and leisure services to increase well-being, in Romania, there is no link between the healthcare system and this type of intervention despite its proven potential to contribute to various positive outcomes, such as increased self-esteem, improved psychological well-being, reduced symptoms of anxiety and depression, enhanced physical health, reduced social isolation and loneliness, and the acquisition of new skills [

58].

For sustainable long-term preventive care, it is important to establish strong links between primary care providers (such as GPs) and non-governmental organizations (NGOs) active in the areas of well-being. Collaboration and coordination among these groups can guarantee an exhaustive and holistic approach to social prescribing in which individuals have access to a diverse range of community-based resources and support services. To accomplish this, GPs and primary care teams must be aware of and familiar with the available local resources. This implies ongoing communication and information exchange among primary care practitioners, non-governmental organizations, and other important stakeholders. Training programs that promote collaboration among GPs and community healthcare professionals, such as community healthcare assistants, can improve the implementation and effectiveness of social prescribing initiatives. We acknowledge the existence of the Map of Social Services in Romania, the first national data platform that centralizes and integrates on an interactive map all the accredited social services in Romania specific to each category of vulnerable groups and a step forward in bridging the gap between healthcare and social interventions [

32].

However, there is more to be done. Researchers must commit to identifying and prioritizing the precise needs and activities that benefit the community the most to build focused and customized social prescribing programs. Conducting research to better understand the local context, current health conditions, and community preferences can help guide the design and execution of effective and sustainable social prescribing programs.

6. Conclusions

We acknowledge that social prescribing is a relatively new concept in Romania with limited research available. However, social prescribing exists in Romania, even if it is not formalized as such, and our focus was to identify activities that have shown potential benefits for managing patients and could serve as a starting point for social prescribing initiatives in our country.

In our paper, we analyzed the populations that already benefit from social prescriptions, especially those belonging to vulnerable groups (the elderly, abandoned children, female victims of violence, immigrants, etc.). We observed various governmental and non-governmental organizations offering different services, but what is clear is that these initiatives are not connected to the healthcare system and that there is no systematic referral from healthcare workers to these services. The missing link, as is well demonstrated in the studied literature, is link workers, who could improve access for those in need of support services. Some of the recent governmental initiatives (integrated community health centers) have the potential for sustainable cooperation between actors of primary care.

Another important finding from our study is that, in the field of well-being, there is little awareness of the need for support services both from the perspective of the community and the perspective of the healthcare system. We believe that it is important to increase the awareness of social prescribing in the preventative field.

By examining the existing evidence and considering the specific needs and context of Romanian patients, we aimed to lay the groundwork for the development and implementation of social prescribing interventions tailored to our population and our healthcare system, in primary care, as well as the sustainability of the initiative by focusing on collaborations among primary care providers, NGOs, community organizations, local authorities, and other pertinent actors.

In conclusion, stronger processes and research are needed in Romania to improve the implementation of social prescribing programs and to document health policies. This includes an awareness of the concept, a focus on prevention, the strengthening of partnerships between primary care providers and governmental and non-governmental organizations, raising the awareness of available resources, fostering collaboration within healthcare teams, and conducting studies to identify and prioritize specific needs and activities that would contribute to the population’s well-being.

One of the first steps is for the GP to identify patients with a wide range of social, emotional, or practical needs who could benefit from social prescribing schemes. By addressing these aspects, we could fully benefit from social prescribing initiatives and unburden the healthcare system of unnecessary services, making it more sustainable and cost-efficient and, at the same time, improving the health and quality of life in Romania.

7. Limitations

This study is a scoping review, and it was aimed at mapping a broad image of the capacity of social prescribing in a country context. However, deeper and more detailed approaches for specific interventions and different populations are important to understand what changes need to be implemented, both in the social and healthcare systems.