Sustainability Matters: Unravelling the Power of ESG in Fostering Brand Love and Loyalty across Generations and Product Involvements

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Environmental, Social, and Corporate Governance (ESG) in the Digital Era

2.2. Brand Love and Brand Loyalty

2.3. Product Involvement and Generational Difference as Moderators

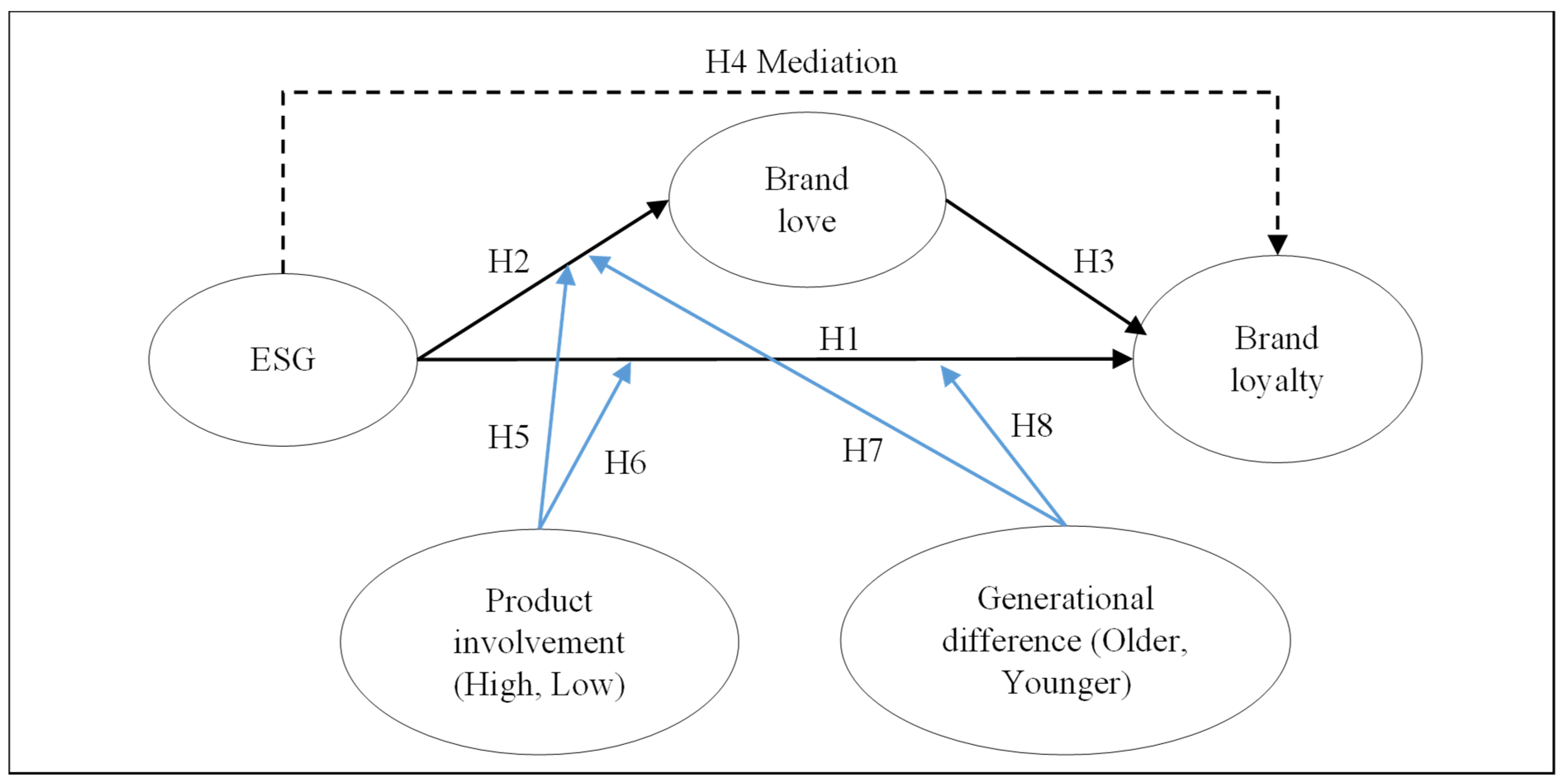

3. Conceptual Framework and Hypothesis Development

4. Research Methodology

5. Results

5.1. Sample Profile

5.2. Hypothesis Testing

5.2.1. Evaluation of the Measurement Model

5.2.2. Evaluation of the Structural Model

5.2.3. Mediation Analysis

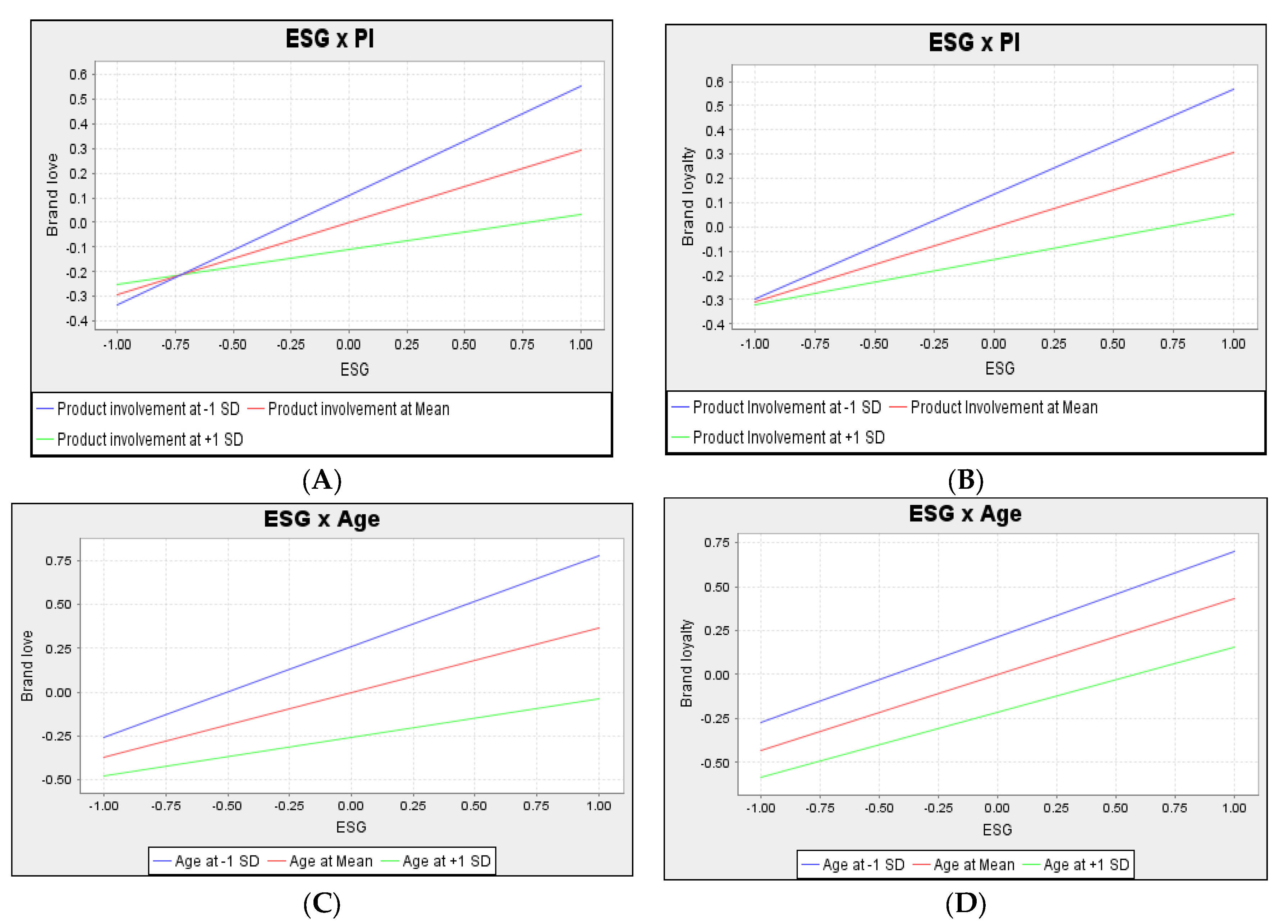

5.2.4. Moderated Mediation Analysis

6. Discussion and Implications

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Koh, H.-K.; Burnasheva, R.; Suh, Y.G. Perceived ESG (Environmental, Social, Governance) and Consumers’ Responses: The Mediating Role of Brand Credibility, Brand Image, and Perceived Quality. Sustainability 2022, 14, 4515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duckler, M. ESG: Brand Strategy and Positioning Through Greater Societal Purpose. 2022. Available online: https://www.fullsurge.com/blog/why-esg-is-more-important-than-ever-for-brands (accessed on 29 May 2023).

- Lee, M.T.; Raschke, R.L.; Krishen, A.S. Signaling green! firm ESG signals in an interconnected environment that promote brand valuation. J. Bus. Res. 2021, 138, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puriwat, W.; Tripopsakul, S. From ESG to DESG: The Impact of DESG (Digital Environmental, Social, and Governance) on Customer Attitudes and Brand Equity. Sustainability 2022, 14, 10480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y. Why Digital Transformation and Non-Financial Reporting Go Hand in Hand. 2023. Available online: https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2023/01/digital-transformation-new-it-esg-davos-23/ (accessed on 29 May 2023).

- Kwak, M.-K.; Cha, S.-S. Can Coffee Shops That Have Become the Red Ocean Win with ESG? J. Distrib. Sci. 2022, 20, 83–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Zein, S.A.; Consolacion-Segura, C.; Huertas-Garcia, R. The role of sustainability in brand equity value in the financial sector. Sustainability 2020, 12, 254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitelock, V. Relationship between Environmental Social Governance (ESG) Management and Performance—The Role of Collaboration in the Supply Chain. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Toledo, Toledo, OH, USA, 2015. Available online: http://rave.ohiolink.edu/etdc/view?acc_num=toledo1450087632 (accessed on 29 May 2023).

- Landrum, S. Millennials Driving Brands to Practice Socially Responsible Marketing. Forbes Magazin, 17 May 2017. Available online: https://www.forbes.com/sites/sarahlandrum/2017/03/17/millennials-driving-brands-to-practice-socially-responsible-marketing/ (accessed on 29 May 2023).

- Sierra, V.; Iglesias, O.; Markovic, S.; Singh, J.J. Does ethical image build equity in corporate services brands? The influence of customer perceived ethicality on effect, perceived quality, and equity. J. Bus. Ethics 2017, 144, 661–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, E.-J. Empathy can increase customer equity related to prosocial brands. J. Bus. Res. 2016, 69, 3748–3754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitra, S.; Pittaluga, E. Digital Transformation and Environmental, Social & Governance: A Perfect Synergy for Today’s Rapidly Evolving World. Treasury and Trade Solutions. 2021. Available online: https://www.citibank.com/tts/insights/assets/docs/articles/2063965_ESG-Article.pdf (accessed on 29 May 2023).

- Valdez, M. Top 3 Reasons Why Digital Transformation Is Key to the ‘E’ In ESG. 2022. Available online: https://opportune.com/insights/article/top-3-reasons-why-digital-transformation-is-key-to-the-e-in-esg/ (accessed on 29 May 2023).

- Di Vaio, A.; Palladino, R.; Hassan, R.; Escobar, O. Artificial intelligence and business models in the sustainable development goals perspective: A systematic literature review. J. Bus. Res. 2020, 121, 283–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Giudice, M.; Di Vaio, A.; Hassan, R.; Palladino, R. Digitalization and new technologies for sustainable business models at the ship–port interface: A bibliometric analysis. Marit. Policy Manag. 2022, 49, 410–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Vaio, A.; Latif, B.; Gunarathne, N.; Gupta, M.; D’Adamo, I. Digitalization and artificial knowledge for accountability in SCM: A systematic literature review. J. Enterp. Inf. Manag. 2023. ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carroll, B.A.; Ahuvia, A.C. Some antecedents and outcomes of brand love. Mark. Lett. 2006, 17, 79–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batra, R.; Ahuvia, A.; Bagozzi, R.P. Brand love. J. Mark. 2012, 76, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gumparthi, V.P.; Patra, S. The phenomenon of brand love: A systematic literature review. J. Relatsh. Mark. 2020, 19, 93–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sternberg, R.J. A triangular theory of love. Psychol. Rev. 1986, 93, 119–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Junaid, M.; Hussain, K.; Hou, F. Addressing the dichotomy of brand love. Int. J. Mark. Res. 2019, 61, 577–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warren, C.; Batra, R.; Loureiro, S.M.C.; Bagozzi, R.P. Brand coolness. J. Mark. 2019, 83, 36–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albert, N.; Merunka, D.; Valette-Florence, P. When consumers love their brands: Exploring the concept and its dimensions. J. Bus. Res. 2008, 61, 1062–1075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliver, R.L. Whence consumer loyalty? J. Mark. 1999, 63 (Suppl. S1), 33–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watanuki, S. Neural mechanisms of brand love relationship dynamics: Is the development of brand love relationships the same as that of interpersonal romantic love relationships? Front. Neurosci. 2022, 16, 984647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagozzi, R.P. Philosophical foundations of concepts and their representation and use in explanatory frameworks. In Measurement in Marketing; Emerald Publishing Limited: Bingley, UK, 2022; Volume 19, pp. 5–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albert, N.; Merunka, D. The role of brand love in consumer-brand relationships. J. Consum. Mark. 2013, 30, 258–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robertson, J.; Botha, E.; Ferreira, C.; Pitt, L. How deep is your love? The brand love-loyalty matrix in consumer-brand relationships. J. Bus. Res. 2022, 149, 651–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baena, V. The importance of CSR practices carried out by sport teams and its influence on brand love: The Real Madrid Foundation. Soc. Responsib. J. 2018, 14, 61–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, Z.; Lew, Y.K.; Park, B.I. Institutional legitimacy and norms-based CSR marketing practices: Insights from MNCs operating in a developing economy. Int. Mark. Rev. 2015, 32, 463–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Javed, A.; Khan, Z. Fostering sustainable relationships in Pakistani cellular service industry through CSR and brand love. S. Asian J. Bus. Stud. 2021, 12, 293–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.J.; Rhee, T.-H. How Does Corporate ESG Management Affect Consumers’ Brand Choice? Sustainability 2023, 15, 6795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaichkowsky, J.L. Measuring the involvement construct. J. Consum. Res. 1985, 12, 341–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, K.; Srinivasan, N. An empirical assessment of multiple operationalizations of involvement. ACR N. Am. Adv. 1990, 17, 594–602. Available online: https://www.acrwebsite.org/volumes/7071 (accessed on 29 May 2023).

- Roe, D.; Bruwer, J. Self-concept, product involvement and consumption occasions: Exploring fine wine consumer behaviour. Br. Food J. 2017, 119, 1362–1377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zdravkovic, S. Does country-of-origin matter to Generation Y? Young Consum. 2013, 14, 89–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, Y.-B.; Seo, Y.-W. The Effect of Domestic Corporations’ ESG Activities on Purchase Intentions through Psychological Distance: Analysis of Differences by Product Involvement Level. J. Korea Contents Assoc. 2021, 21, 217–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Poon, P.; Huang, G. Corporate ability and corporate social responsibility in a developing country: The role of product involvement. J. Glob. Mark. 2012, 25, 45–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Titko, J.; Svirina, A.; Tambovceva, T.; Skvarciany, V. Differences in attitude to corporate social responsibility among generations. Sustainability 2021, 13, 10944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hommerová, D.; Šrédl, K.; Vrbková, L.; Svoboda, R. The perception of CSR activities in a selected segment of McDonald’s customers in the Czech Republic and its effect on their purchasing behavior—A case study. Sustainability 2020, 12, 8627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shauki, E. Perceptions on corporate social responsibility: A study in capturing public confidence. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2011, 18, 200–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wisse, B.; Van Eijbergen, R.; Rietzschel, E.F.; Scheibe, S. Catering to the needs of an aging workforce: The role of employee age in the relationship between corporate social responsibility and employee satisfaction. J. Bus. Ethics 2018, 147, 875–888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haski-Leventhal, D.; Pournader, M.; McKinnon, A. The role of gender and age in business students’ values, CSR attitudes, and responsible management education: Learnings from the PRME international survey. J. Bus. Ethics 2017, 146, 219–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruegger, D.; King, E.W. A study of the effect of age and gender upon student business ethics. J. Bus. Ethics 1992, 11, 179–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, J.E.; Hu, H. The effect of service quality on trust and commitment varying across generations. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2009, 33, 468–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eweje, G.; Brunton, M. Ethical perceptions of business students in a New Zealand university: Do gender, age and work experience matter? Bus. Ethics Eur. Rev. 2010, 19, 95–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gholipour, T.H.; Nayeri, M.D.; Mehdi, S.M.M. Investigation of attitudes about corporate social responsibility: Business students in Iran. Afr. J. Bus. Manag. 2012, 6, 5105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, J.; Kandampully, J. The role of emotional aspects in younger consumer-brand relationships. J. Prod. Brand Manag. 2012, 21, 98–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nawaz, S.; Jiang, Y.; Alam, F.; Nawaz, M.Z. Role of brand love and consumers’ demographics in building consumer–brand relationship. SAGE Open 2020, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lutkevich, B. ESG vs. CSR vs. Sustainability: What’s the Difference? 2022. Available online: https://www.techtarget.com/whatis/feature/ESG-vs-CSR-vs-sustainability-Whats-the-difference (accessed on 29 May 2023).

- Bangkok Post. Firms Vow ESG Principles Are Here to Stay. 2022. Available online: https://www.bangkokpost.com/business/2441224/firms-vow-esg-principles-are-here-to-stay (accessed on 29 May 2023).

- Chin, W.W. How to write up and report PLS analyses. In Handbook of Partial Least Squares: Concepts, Methods and Applications; Esposito Vinzi, V., Chin, W., Henseler, J., Wang, H., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2009; pp. 655–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moisescu, O.I. Development and Validation of a Measurement Scale for Customers’ perceptions of Corporate Social Responsibility. Manag. Mark. J. 2015, 13, 311–332. Available online: https://www.mnmk.ro/documents/2016_X1/Articol_4.pdf (accessed on 29 May 2023).

- Maignan, I. Consumers’ perceptions of corporate social responsibilities: A cross-cultural comparison. J. Bus. Ethics 2001, 30, 57–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Los Salmones, M.D.M.G.; Crespo, A.H.; del Bosque, I.R. Influence of corporate social responsibility on loyalty and valuation of services. J. Bus. Ethics 2005, 61, 369–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohr, L.A.; Webb, D.J. The effects of corporate social responsibility and price on consumer responses. J. Consum. Aff. 2005, 39, 121–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker-Olsen, K.L.; Taylor, C.R.; Hill, R.P.; Yalcinkaya, G.; Zeriti, A.; Robson, M.J.; Spyropoulou, S.; Leonidou, C.N.; Madden, T.J.; Roth, M.S.; et al. A cross-cultural examination of corporate social responsibility marketing communications in Mexico and the United States: Strategies for global brands. J. Int. Mark. 2011, 19, 30–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, T.; Bicen, P.; Hall, Z.R. The dark side of retailing: Towards a scale of corporate social irresponsibility. Int. J. Retail. Distrib. Manag. 2008, 36, 124–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turker, D. Measuring corporate social responsibility: A scale development study. J. Bus. Ethics 2008, 85, 411–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Öberseder, M.; Schlegelmilch, B.B.; Murphy, P.E.; Gruber, V. Consumers’ perceptions of corporate social responsibility: Scale development and validation. J. Bus. Ethics 2014, 124, 101–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez, A.; del Bosque, I.R. Measuring CSR image: Three studies to develop and to validate a reliable measurement tool. J. Bus. Ethics 2013, 118, 265–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandhachitara, R.; Poolthong, Y. A model of customer loyalty and corporate social responsibility. J. Serv. Mark. 2011, 25, 122–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, M.T.H. The impact of brand love on brand loyalty: The moderating role of self-esteem, and social influences. Span. J. Mark.-ESIC 2021, 25, 156–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mrad, M.; Cui, C.C. Brand addiction: Conceptualization and scale development. Eur. J. Mark. 2017, 51, 1938–1960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karaatli, G. The Purchasing Involvement Scale. J. Mark. Dev. Compet. 2015, 9, 72–79. Available online: https://scholar.valpo.edu/cba_fac_pub/24 (accessed on 29 May 2023).

- Henseler, J.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. Testing measurement invariance of composites using partial least squares. Int. Mark. Rev. 2016, 33, 405–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Black, W.C.; Babin, B.J.; Anderson, R.E. Multivariate Data Analysis: A Global Perspective; Pearson Education: London, UK, 2010; pp. 266–316. Available online: https://www.gbv.de/dms/ilmenau/toc/586907149.PDF (accessed on 29 May 2023).

- Sarstedt, M.; Hair, J.F.; Ringle, C.M.; Thiele, K.O.; Gudergan, S.P. Estimation issues with PLS and CBSEM: Where the bias lies! J. Bus. Res. 2016, 69, 3998–4010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henseler, J.; Hubona, G.; Ray, P.A. Using PLS path modeling in new technology research: Updated guidelines. Ind. Manag. Data Syst. 2016, 116, 2–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. PLS-SEM: Indeed a silver bullet. J. Mark. Theory Pract. 2011, 19, 139–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falk, R.F.; Miller, N.B. A Primer for Soft Modeling; University of Akron Press: Akron, OH, USA, 1992; Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/232590534_A_Primer_for_Soft_Modeling (accessed on 29 May 2023).

- Cohen, J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences, 2nd ed.; Erlbaum: Hillsdale, NJ, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Lynch, J.G., Jr.; Chen, Q. Reconsidering Baron and Kenny: Myths and truths about mediation analysis. J. Consum. Res. 2010, 37, 197–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheah, J.-H.; Nitzl, C.; Roldan, J.L.; Cepeda-Carrion, G.; Gudergan, S.P. A primer on the conditional mediation analysis in PLS-SEM. ACM SIGMIS Database DATABASE Adv. Inf. Syst. 2021, 52, 43–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, A.F. Partial, conditional, and moderated moderated mediation: Quantification, inference, and interpretation. Commun. Monogr. 2018, 85, 4–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latif, K.F. Series 35—Moderated Mediation in SmartPLS. Youtube. 10 July 2022. Educational Video; 15.13.. Available online: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jwL2RuZJ1gI (accessed on 29 May 2023).

- Rodrigues, P.; Costa, P. The effect of the consumer perceptions of CSR in brand love. In Proceedings of the 12th Global Brand Conference of the Academy of Marketing, Kalmar, Sweden, 26–28 April 2017; pp. 26–27. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/317264762_The_Effect_of_the_Consumers_Perception_of_CSR_in_Brand_Love (accessed on 29 May 2023).

- Quezado, T.C.C.; Fortes, N.; Cavalcante, W.Q.F. The influence of corporate social responsibility and business ethics on brand fidelity: The importance of brand love and brand attitude. Sustainability 2022, 14, 2962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akbari, M.; Mehrali, M.; Seyyedamiri, N.; Rezaei, N.; Pourjam, A. Corporate social responsibility, customer loyalty and brand positioning. Soc. Responsib. J. 2020, 16, 671–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Y.; Lai, K.K. The effect of corporate social responsibility on brand loyalty: The mediating role of brand image. Total Qual. Manag. Bus. Excel. 2014, 25, 249–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, K.-M.; Nobi, B.; Kim, T. CSR and brand resonance: The mediating role of brand love and involvement. Sustainability 2020, 12, 4159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Kim, M.; Im, S.; Choi, D. Competitiveness of E Commerce firms through ESG logistics. Sustainability 2021, 13, 11548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Constructs | Items | Observed Variables |

|---|---|---|

| Refer to any programs or campaigns that represent a company’s commitment to social, environmental, and ethical business practices while facilitating interactions and transactions between you and the firm or brand, the (NAME)… | ||

| Environmental dimension (ED) | ED1 | Takes every effort to reduce or get rid of negative environmental consequences. |

| ED2 | Minimizes resource usage without endangering the environment. | |

| ED3 | Uses environmentally friendly materials with a strong commitment. | |

| ED4 | Focuses on the effective management of waste and recycling disposal activities. | |

| Social dimension (SD) | SD1 | Respects culture, traditions, and social norms. |

| SD2 | Enhances societal well-being and people’s quality of life over the long term. | |

| SD3 | Aids in the growth of society and the economy. | |

| SD4 | Supports charities that work to improve the lives of disadvantaged people. | |

| Governance dimension (GD) | GD1 | Strictly adheres to the law when conducting its business. |

| GD2 | Is focused on fulfilling its obligations to its partners and stockholders. | |

| GD3 | Has an ethical standards policy that takes precedence over financial performance. | |

| GD4 | Goes out of its way to avoid and prevent corruption in its dealings with the country. | |

| Brand love (BO) | BO1 | How strongly do you feel compelled to use this firm (or brand)? |

| BO2 | Please describe the degree to which you believe you naturally “fit” with this firm (or brand). | |

| BO3 | Please rate how well this firm (or brand) seems to match your personal preferences. | |

| BO4 | Please describe the degree to which you anticipate having a long-term relationship with the firm (or brand). | |

| Brand loyalty (BL) | BL1 | I will buy this firm (or brand) next time. |

| BL2 | I intend to purchase this firm (or brand). | |

| BL3 | I commit to this firm (or brand). | |

| BL4 | In comparison to switching to other brands, I would be willing to pay more for this firm (or brand). | |

| Refer to the kind of products that you recalled ESG initiatives… | ||

| Product involvement (PI) | PI1 | You carefully select products of this type. |

| PI2 | This category of products is a topic that might be discussed at length. | |

| PI3 | You feel the need to evaluate as many options as possible to ensure that you get the greatest product. | |

| PI4 | You are concerned about the outcome of your decision while selecting products in this category. | |

| PI5 | The brands of products you purchase make a substantial difference to you. | |

| Item | Description | Sample | (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Female | 83 | 53.5 |

| Male | 73 | 46.5 | |

| Age | 18–25 | 36 | 23.2 |

| 26–35 | 46 | 29.8 | |

| 36–45 | 48 | 30.8 | |

| 46–55 | 17 | 10.6 | |

| More than 55 years | 9 | 5.6 | |

| Marital status | Single | 83 | 53.5 |

| Married | 71 | 45.3 | |

| Others | 2 | 1.2 | |

| Education | Below undergraduate | 23 | 14.7 |

| Undergraduate | 77 | 49.6 | |

| Postgraduate | 56 | 35.7 | |

| Income (USD) | Below 978 | 63 | 40.5 |

| 979–2794 | 68 | 43.4 | |

| Above 2794 | 25 | 16.1 |

| Constructs | Items | Outer Loadings | Cronbach’s α | CR | AVE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ED | ED1 | 0.822 | 0.858 | 0.904 | 0.704 |

| ED2 | 0.904 | ||||

| ED3 | 0.880 | ||||

| ED4 | 0.740 | ||||

| SD | SD1 | 0.872 | 0.860 | 0.906 | 0.707 |

| SD2 | 0.910 | ||||

| SD3 | 0.822 | ||||

| SD4 | 0.749 | ||||

| GD | GD1 | 0.848 | 0.857 | 0.904 | 0.702 |

| GD2 | 0.902 | ||||

| GD3 | 0.843 | ||||

| GD4 | 0.752 | ||||

| BO | BO1 | 0.876 | 0.836 | 0.891 | 0.671 |

| BO2 | 0.822 | ||||

| BO3 | 0.815 | ||||

| BO4 | 0.761 | ||||

| BL | BL1 | 0.882 | 0.834 | 0.890 | 0.669 |

| BL2 | 0.814 | ||||

| BL3 | 0.742 | ||||

| BL4 | 0.828 | ||||

| PI | PI1 | 0.727 | 0.834 | 0.883 | 0.602 |

| PI2 | 0.834 | ||||

| PI3 | 0.726 | ||||

| PI4 | 0.787 | ||||

| PI5 | 0.798 | ||||

| ESG | ED | 0.802 | 0.856 | 0.854 | 0.661 |

| SD | 0.813 | ||||

| GD | 0.824 |

| Latent Variable | BL | BO | ED | GD | SD | PI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fornell-Larcker criterion | ||||||

| BL | 0.818 | |||||

| BO | 0.461 | 0.819 | ||||

| ED | 0.163 | 0.318 | 0.839 | |||

| GD | 0.389 | 0.553 | 0.262 | 0.838 | ||

| SD | 0.394 | 0.500 | 0.284 | 0.440 | 0.841 | |

| PI | 0.369 | 0.433 | 0.105 | 0.445 | 0.264 | 0.776 |

| Heterotrait-Monotrait Ratio | ||||||

| BO | 0.546 | |||||

| ED | 0.188 | 0.370 | ||||

| GD | 0.454 | 0.656 | 0.305 | |||

| SD | 0.471 | 0.586 | 0.327 | 0.509 | ||

| PI | 0.431 | 0.517 | 0.128 | 0.525 | 0.314 | |

| H | Hypothesized Relationship | Path Coefficient | f2 | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | ESG → BL | 0.418 *** | 0.425 | Supported |

| 2 | ESG → BO | 0.627 *** | 0.648 | Supported |

| 3 | BO → BL | 0.348 *** | 0.193 | Supported |

| H | Relationship | Mediator | Direct Effect | Indirect Effect | Type of Mediation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H4 | ESG → BL | BO | 0.418 *** | 0.255 *** | Partially mediation |

| H | Original Sample (O) | Sample Mean (M) | SE | t Values | p Values | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5 | ESG × PI → BO → BL | −0.144 | −0.146 | 0.054 | 3.769 | 0.000 | Supported |

| 6 | ESG × PI → BL | −0.151 | −0.152 | 0.040 | 4.156 | 0.000 | Supported |

| 7 | ESG × Age → BO → BL | −0.138 | −0.136 | 0.041 | 3.382 | 0.001 | Supported |

| 8 | ESG × Age → BL | −0.074 | −0.078 | 0.059 | 1.271 | 0.204 | Rejected |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Puriwat, W.; Tripopsakul, S. Sustainability Matters: Unravelling the Power of ESG in Fostering Brand Love and Loyalty across Generations and Product Involvements. Sustainability 2023, 15, 11578. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151511578

Puriwat W, Tripopsakul S. Sustainability Matters: Unravelling the Power of ESG in Fostering Brand Love and Loyalty across Generations and Product Involvements. Sustainability. 2023; 15(15):11578. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151511578

Chicago/Turabian StylePuriwat, Wilert, and Suchart Tripopsakul. 2023. "Sustainability Matters: Unravelling the Power of ESG in Fostering Brand Love and Loyalty across Generations and Product Involvements" Sustainability 15, no. 15: 11578. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151511578

APA StylePuriwat, W., & Tripopsakul, S. (2023). Sustainability Matters: Unravelling the Power of ESG in Fostering Brand Love and Loyalty across Generations and Product Involvements. Sustainability, 15(15), 11578. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151511578