Effects of Risk Attitude and Time Pressure on the Perceived Risk and Avoidance of Mobile App Advertising among Chinese Generation Z Consumers

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Literature Review and Hypotheses Development

2.1. Ad Avoidance

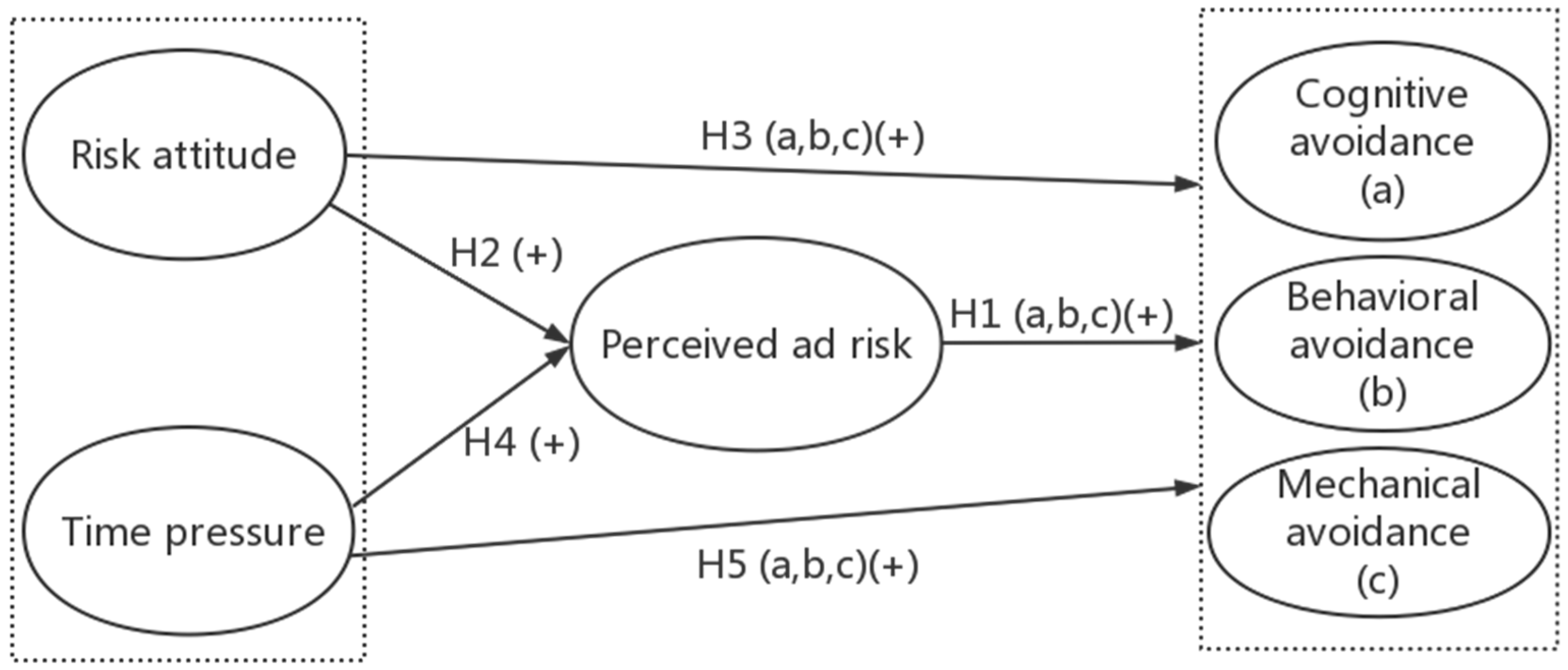

2.2. Hypothesis Development

2.2.1. Perceived Risk and Ad Avoidance

2.2.2. Risk Attitude, Perceived Ad Risk, and Ad Avoidance

2.2.3. Time Pressure, Perceived Ad Risk, and Ad Avoidance

3. Methods

3.1. Sampling and Data Gathering

3.2. Measures

4. Data Analysis and Results

4.1. Measurement Model

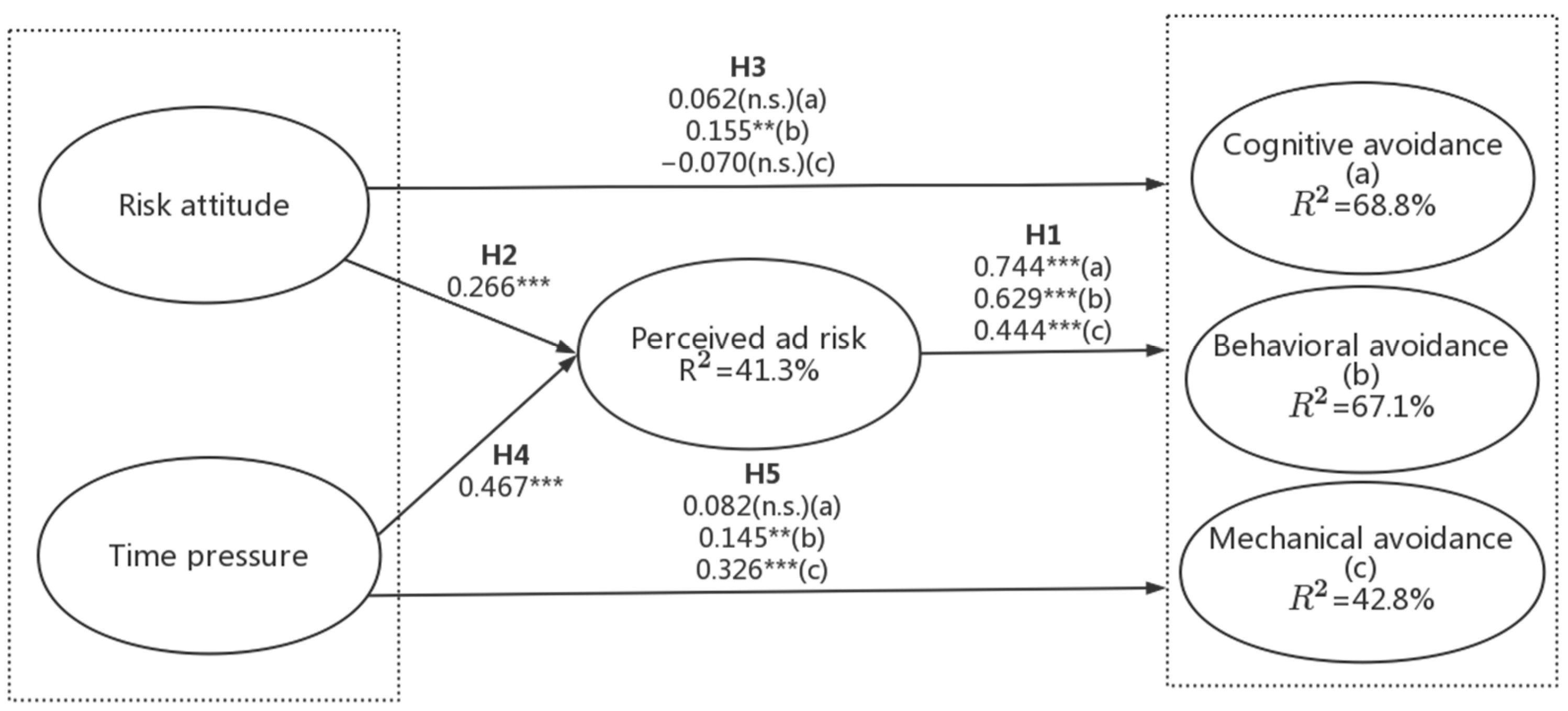

4.2. Structural Model and Hypotheses Testing

5. Discussion

5.1. Main Findings

5.2. Theoretical Contribution

5.3. Practical Implications

6. Limitations and Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Al-Adwan, A.S.; Sammour, G. What makes consumers purchase mobile apps: Evidence from Jordan. J. Theor. Appl. Electron. Commer. Res. 2020, 16, 562–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Data.ai. The State of Mobile in 2022: How to Succeed in a Mobile-First World as Consumers Spend 3.8 Trillion Hours on Mobile Devices. 2022. Available online: https://www.data.ai/en/insights/market-data/state-of-mobile-2022/ (accessed on 7 June 2023).

- Sydow, L. State of Mobile 2023: Focus on China, Korea and Japan. 2023. Available online: https://www.data.ai/en/insights/market-data/state-of-mobile-apps-2023-focus-on-north-asia/ (accessed on 7 June 2023).

- Gao, C.; Zeng, J.; Lo, D.; Xia, X.; King, I.; Lyu, M.R. Understanding in-app advertising issues based on large scale app review analysis. Inf. Softw. Technol. 2022, 142, 106741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- APP Industry Data Analysis: 48.4% of Chinese Internet Users Resent APP Ads in 2021 Because They Can’t Close Them. 2021. Available online: https://www.sohu.com/a/474243807_120205287 (accessed on 7 June 2023).

- Shin, W.; Lwin, M.O.; Yee, A.Z.H.; Kee, K.M. The role of socialization agents in adolescents’ responses to app-based mobile advertising. Int. J. Advert. 2020, 39, 365–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Speck, P.S.; Elliott, M.T. Predictors of Advertising Avoidance in Print and Broadcast Media. J. Advert. 1997, 26, 61–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Redondo, I.; Aznar, G. Whitelist or Leave Our Website! Advances in the Understanding of User Response to Anti-Ad-Blockers. Informatics 2023, 10, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wielki, J.; Grabara, J. The impact of Ad-blocking on the sustainable development of the digital advertising ecosystem. Sustainability 2018, 10, 4039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Redondo, I.; Aznar, G. To use or not to use ad blockers? The roles of knowledge of ad blockers and attitude toward online advertising. Telemat. Inform. 2018, 35, 1607–1616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rathee, S.; Milfeld, T. Sustainability advertising: Literature review and framework for future research. Int. J. Advert. 2023, 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, L.; Kerr, G.; Drennan, J.; Fazal-E-Hasan, S.M. Feel, think, avoid: Testing a new model of advertising avoidance. J. Mark. Commun. 2019, 27, 343–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hazari, S.; Sethna, B.N. A Comparison of Lifestyle Marketing and Brand Influencer Advertising for Generation Z Instagram Users. J. Promot. Manag. 2023, 29, 491–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munsch, A. Millennial and generation Z digital marketing communication and advertising effectiveness: A qualitative exploration. J. Glob. Sch. Mark. Sci. 2021, 31, 10–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grigoreva, E.A.; Garifova, L.F.; Polovkina, E.A. Consumer Behavior in the Information Economy: Generation Z. Int. J. Financ. Res. 2021, 12, 164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szymkowiak, A.; Melović, B.; Dabić, M.; Jeganathan, K.; Kundi, G.S. Information technology and Gen Z: The role of teachers, the internet, and technology in the education of young people. Technol. Soc. 2021, 65, 101565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimand-Sheiner, D.; Ryan, T.; Kip, S.M.; Lahav, T. Native advertising credibility perceptions and ethical attitudes: An exploratory study among adolescents in the United States, Turkey and Israel. J. Bus. Res. 2020, 116, 608–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meet, R.K.; Kala, D.; Al-Adwan, A.S. Exploring factors affecting the adoption of MOOC in Generation Z using extended UTAUT2 model. Educ. Inf. Technol. 2022, 27, 10261–10283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Wang, Y.; Hwang, J. Generation Z in China: Implications for Global Brands. In The New Generation Z in Asia: Dynamics, Differences, Digitalisation; Gentina, E., Parry, E., Eds.; Emerald Publishing Limited: Bingley, UK, 2020; pp. 23–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meghisan-Toma, G.-M.; Puiu, S.; Florea, N.M.; Meghisan, F.; Doran, D.; Research, A.E.C. Generation Z’young adults and M-commerce use in Romania. J. Theor. Appl. Electron. Commer. Res. 2021, 16, 1458–1471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Southgate, D. The Emergence of Generation Z And Its Impact in Advertising. J. Advert. Res. 2017, 57, 227–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKee, K. Actions Speak Louder than Words: How Social Influence Affects Gen Z’S Attitude toward Personalized Marketing, Brand Loyalty, Ad Avoidance, and Brand Avoidance Behaviors; University of Wisconsin-Whitewater: Whitewater, WI, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Chatterjee, P. Are Unclicked Ads Wasted ? Enduring Effects of Banner and Pop-Up Ad Exposures on Brand Memory and Attitudes. J. Electron. Commer. Res. 2008, 9, 51–61. [Google Scholar]

- Dodoo, N.A.; Wen, J. Weakening the avoidance bug: The impact of personality traits in ad avoidance on social networking sites. J. Mark. Commun. 2020, 27, 457–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Youn, S.; Kim, S. Understanding ad avoidance on Facebook: Antecedents and outcomes of psychological reactance. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2019, 98, 232–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards, G. How Many People Use Ad Blockers? And What Does It Mean for My Adspend. 2022. Available online: https://blog.cipio.ai/how-many-people-use-ad-blockers (accessed on 7 June 2023).

- Rus-Arias, E.; Palos-Sanchez, P.R.; Reyes-Menendez, A. The Influence of Sociological Variables on Users’ Feelings about Programmatic Advertising and the Use of Ad-Blockers. Informatics 2021, 8, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çelik, F.; Çam, M.S.; Koseoglu, M.A. Ad avoidance in the digital context: A systematic literature review and research agenda. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2022. early view. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.J.; Yue, X.L.; Ansari, A.R.; Tang, G.Q.; Ding, J.Y.; Jiang, Y.Q. Research on the Influence Mechanism of Consumers’ Perceived Risk on the Advertising Avoidance Behavior of Online Targeted Advertising. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 878629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hwang, J.; Choe, J.Y. How to enhance the image of edible insect restaurants: Focusing on perceived risk theory. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2020, 87, 102464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, W.-Y.; Chang, M.-L. The role of risk attitude on online shopping: Experience, customer satisfaction, and repurchase intention. Soc. Behav. Pers. Int. J. 2007, 35, 453–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dohmen, T.; Falk, A.; Huffman, D.; Sunde, U.; Schupp, J.; Wagner, G.G. Individual Risk Attitudes: Measurement, Determinants, and Behavioral Consequences. J. Eur. Econ. Assoc. 2011, 9, 522–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pan, D.; He, M.; Kong, F. Risk attitude, risk perception, and farmers’ pesticide application behavior in China: A moderation and mediation model. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 276, 124241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qazi, A.; Daghfous, A.; Khan, M.S. Impact of risk attitude on risk, opportunity, and performance assessment of construction projects. Proj. Manag. J. 2021, 52, 192–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, M.A. A Quantitative Assessment of the Factors That Predict Mobile Advertising Technology Acceptance; Northcentral University: Scottsdale, AZ, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Amirpur, M.; Benlian, A. Buying under Pressure: Purchase Pressure Cues and their Effects on Online Buying Decisions. In Proceedings of the Thirty Sixth International Conference on Information Systems, Fort Worth 2015, Fort Worth, TX, USA, 13–16 December 2015; pp. 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Prendergast, G.; Cheung, W.-L.; West, D. Antecedents to Advertising Avoidance in China. J. Curr. Issues Res. Advert. 2010, 32, 87–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rojas-Méndez, J.I.; Davies, G. Time Pressure and Time Planning in Explaining Advertising Avoidance Behavior. J. Promot. Manag. 2017, 23, 481–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, C.-H.; Cheon, H.J. Why Do People Avoid Advertising on the Internet? J. Advert. 2004, 33, 89–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Söllner, J.; Dost, F. Exploring the Selective Use of Ad Blockers and Testing Banner Appeals to Reduce Ad Blocking. J. Advert. 2019, 48, 302–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, J.; Zhang, P.; Wu, P.F. Categorizing consumer behavioral responses and artifact design features: The case of online advertising. Inf. Syst. Front. 2015, 17, 513–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, L.; Kerr, G.; Drennan, J. Triggers of engagement and avoidance: Applying approach-avoid theory. J. Mark. Commun. 2018, 26, 488–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, L.L.; Maier, E. Interactive ad avoidance on mobile phones. J. Advert. 2022, 51, 440–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gordon, B.R.; Jerath, K.; Katona, Z.; Narayanan, S.; Shin, J.; Wilbur, K.C. Inefficiencies in digital advertising markets. J. Mark. 2021, 85, 7–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Yan, S.; Miller, K.M.; Skiera, B. How does the adoption of ad blockers affect news consumption? J. Mark. Res. 2022, 59, 1002–1018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brinson, N.H.; Britt, B.C. Reactance and turbulence: Examining the cognitive and affective antecedents of ad blocking. J. Res. Interact. Mark. 2021, 15, 549–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Todri, V. Frontiers: The Impact of Ad-Blockers on Online Consumer Behavior. Mark. Sci. 2022, 41, 7–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchel, V.W. Consumer perceived risk: Conceptualisations and models. Eur. J. Mark. 1999, 33, 163–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, J.; Yuan, G.; Yoo, C. The effect of the perceived risk on the adoption of the sharing economy in the tourism industry: The case of Airbnb. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2020, 57, 102108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thusi, P.; Maduku, D.K. South African millennials’ acceptance and use of retail mobile banking apps: An integrated perspective. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2020, 111, 106405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forsythe, S.M.; Shi, B. Consumer patronage and risk perceptions in Internet shopping. J. Bus. Res. 2003, 56, 867–875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauer, R.A. Consumer behavior as risk taking. In Proceedings of the 43rd National Conference of the American Marketing Assocation, Chicago, IL, USA, 15–17 June 1960. [Google Scholar]

- Cunningham, M.S. The major dimensions of perceived risk. In Risk Taking and Information Handling in Consumer Behavior; Harvard University Press: Boston, MA, USA, 1967. [Google Scholar]

- Pillai, S.G.; Kim, W.G.; Haldorai, K.; Kim, H.-S. Online food delivery services and consumers’ purchase intention: Integration of theory of planned behavior, theory of perceived risk, and the elaboration likelihood model. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2022, 105, 103275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, V.W. Understanding consumers’ behaviour: Can perceived risk theory help? Manag. Decis. 1992, 30, 26–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aiolfi, S.; Bellini, S.; Pellegrini, D. Data-driven digital advertising: Benefits and risks of online behavioral advertising. Int. J. Retail Distrib. Manag. 2021, 49, 1089–1110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, A.-R.; Heo, J. The effects of mobile phone use motives on the intention to use location-based advertising: The mediating role of media affinity and perceived trust and risk. Int. J. Advert. 2022, 41, 930–947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strycharz, J.; Van Noort, G.; Smit, E.; Helberger, N. Protective behavior against personalized ads: Motivation to turn personalization off. Cyberpsychology J. Psychosoc. Res. Cyberspace 2019, 13, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Okazaki, S.; Li, H.; Hirose, M. Consumer Privacy Concerns and Preference for Degree of Regulatory Control. J. Advert. 2009, 38, 63–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chen, Q.; Feng, Y.; Liu, L.; Tian, X. Understanding consumers’ reactance of online personalized advertising: A new scheme of rational choice from a perspective of negative effects. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2019, 44, 53–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozcelik, A.B.; Varnali, K. Effectiveness of online behavioral targeting: A psychological perspective. Electron. Commer. Res. Appl. 2019, 33, 100819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van den Broeck, E.; Poels, K.; Walrave, M. How do users evaluate personalized Facebook advertising? An analysis of consumer- and advertiser controlled factors. Qual. Mark. Res. Int. J. 2020, 23, 309–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, J.; Drumwright, M.; Goo, W. Native Advertising: Is Deception an Asset or a Liability? J. Media Ethics 2018, 33, 102–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Yuan, R.; Luo, J.; Liu, M.J.; Yannopoulou, N. Does personalized advertising have their best interests at heart? A quantitative study of narcissists’ SNS use among Generation Z consumers. J. Bus. Res. 2023, 165, 114070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Winsen, F.; de Mey, Y.; Lauwers, L.; Van Passel, S.; Vancauteren, M.; Wauters, E. Determinants of risk behaviour: Effects of perceived risks and risk attitude on farmer’s adoption of risk management strategies. J. Risk Res. 2016, 19, 56–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, T.-M.; Guo, S.; Liu, N.; Shi, X. Optimal pricing in on-demand-service-platform-operations with hired agents and risk-sensitive customers in the blockchain era. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2020, 284, 1031–1042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolfe, K.; Sirota, M.; Clarke, A.D.F. Age differences in COVID-19 risk-taking, and the relationship with risk attitude and numerical ability. R. Soc. Open Sci. 2021, 8, 201445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowiński, W.; Haddoud, M.Y.; Wach, K.; Schaefer, R. Perceived public support and entrepreneurship attitudes: A little reciprocity can go a long way! J. Vocat. Behav. 2020, 121, 103474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, P.; Cheng, J. Individual differences in social distancing and mask-wearing in the pandemic of COVID-19: The role of need for cognition, self-control and risk attitude. Pers. Individ. Differ. 2021, 175, 110706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molnar, A.; Muntean, C.H. Consumer’ risk attitude based personalisation for content delivery. In Proceedings of the 2012 IEEE Consumer Communications and Networking Conference (CCNC), Las Vegas, NV, USA, 14–17 January 2012; pp. 265–269. [Google Scholar]

- Han, L.; Xiao, J.; Su, Z. Financing knowledge, risk attitude and P2P borrowing in China. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2019, 43, 166–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sun, R.; Meng, J. Looking at young millennials’ risk perception and purchase intention toward GM foods: Exploring the role of source credibility and risk attitude. Health Mark. Q. 2022, 39, 263–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, T.; Lee, J.; Suh, J. L-Shape advertising for mobile video streaming services: Less intrusive while still effective. Displays 2023, 78, 102436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roth-Cohen, O.; Rosenberg, H.; Lissitsa, S. Are you talking to me? Generation X, Y, Z responses to mobile advertising. Converg. Int. J. Res. Into New Media Technol. 2022, 28, 761–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, W.; Lin, T.T.-C. Who avoids location-based advertising and why? Investigating the relationship between user perceptions and advertising avoidance. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2016, 63, 444–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, G.S. A Theory of the Allocation of Time. Econ. J. 1965, 75, 493–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Finucane, M.L.; Alhakami, A.; Slovic, P.; Johnson, S.M. The affect heuristic in judgments of risks and benefits. J. Behav. Decis. Mak. 2000, 13, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.M.; Schulz, E.; Pleskac, T.J.; Speekenbrink, M. Time pressure changes how people explore and respond to uncertainty. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 4122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finucane, M.L. The role of feelings in perceived risk. In Essentials of Risk Theory; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2012; pp. 57–74. [Google Scholar]

- Mou, J.; Shin, D. Effects of social popularity and time scarcity on online consumer behaviour regarding smart healthcare products: An eye-tracking approach. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2018, 78, 74–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kocher, M.G.; Pahlke, J.; Trautmann, S.T. Tempus fugit: Time pressure in risky decisions. Manag. Sci. 2013, 59, 2380–2391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Phillips-Wren, G.; Adya, M. Decision making under stress: The role of information overload, time pressure, complexity, and uncertainty. J. Decis. Syst. 2020, 29, 213–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiese, B.H. Time allocation and dietary habits in the United States: Time for re-evaluation? Physiol. Behav. 2018, 193, 205–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, P.; Roy, R.; Rabbanee, F.K. Interactive effects of situational and enduring involvement with perceived crowding and time pressure in pay-what-you-want (PWYW) pricing. J. Bus. Res. 2020, 109, 88–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, L.; Zhang, W.; Wang, X.; Liang, S. Moderating effects of time pressure on the relationship between perceived value and purchase intention in social E-commerce sales promotion: Considering the impact of product involvement. Inf. Manag. 2019, 56, 317–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, N. Product presentation in the live-streaming context: The effect of consumer perceived product value and time pressure on consumer’s purchase intention. Front. Psychol. 2023, 14, 1124675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Delgado, P.; Salmerón, L. The inattentive on-screen reading: Reading medium affects attention and reading comprehension under time pressure. Learn. Instr. 2021, 71, 101396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, Y.; Lu, Z.; Kuang, H.; Wang, C. Information avoidance behavior on social network sites: Information irrelevance, overload, and the moderating role of time pressure. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2020, 52, 102067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patrick Rau, P.-L.; Zhou, J.; Chen, D.; Lu, T.-P. The influence of repetition and time pressure on effectiveness of mobile advertising messages. Telemat. Inform. 2014, 31, 463–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabachnick, B.G.; Fidell, L.S.; Ullman, J.B. Using Multivariate Statistics; Pearson: Boston, MA, USA, 2013; Volume 6. [Google Scholar]

- Wärneryd, K.-E. Risk attitudes and risky behavior. J. Econ. Psychol. 1996, 17, 749–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laroche, M.; McDougall, G.H.; Bergeron, J.; Yang, Z. Exploring how intangibility affects perceived risk. J. Serv. Res. 2004, 6, 373–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Black, W.C.; Babin, B.J.; Anderson, R.E. Multivariate Data Analysis: Pearson New International Edition PDF eBook; Pearson Higher Education: Boston, MA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutierrez, A.; O’Leary, S.; Rana, N.P.; Dwivedi, Y.K.; Calle, T. Using privacy calculus theory to explore entrepreneurial directions in mobile location-based advertising: Identifying intrusiveness as the critical risk factor. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2019, 95, 295–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Youn, S.; Kim, S. Newsfeed native advertising on Facebook: Young millennials’ knowledge, pet peeves, reactance and ad avoidance. Int. J. Advert. 2019, 38, 651–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zur, H.B.; Breznitz, S.J. The effect of time pressure on risky choice behavior. Acta Psychol. 1981, 47, 89–104. [Google Scholar]

| Characteristics | Frequency | Percentage (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 172 | 55.1 |

| Female | 140 | 44.9 | |

| Age | Under 18 years | 145 | 46.5 |

| 18–26 years | 167 | 53.5 | |

| Educational | Below high school | 16 | 5.1 |

| High school | 184 | 59.0 | |

| College | 39 | 12.5 | |

| Undergraduate | 44 | 14.1 | |

| Graduate | 29 | 9.3 | |

| Time spent on the app | Less than 1 h per day | 20 | 6.4 |

| 1–3 h per day | 61 | 19.6 | |

| 3–5 h per day | 98 | 31.4 | |

| More than 5 h per day | 133 | 42.6 |

| Construct | Factor Loadings | CR | AVE | Cronbach’s Alpha |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Risk attitude (first-order reflective) | 0.877 | 0.641 | 0.875 | |

| Before making any decisions, I will think carefully. | 0.80 | |||

| Before I buy something, I want to learn more about it. | 0.85 | |||

| I steer clear of taking risks. | 0.77 | |||

| To avoid regret later, I would instead take my time comparing options. | 0.78 | |||

| Time pressure (first-order reflective) | 0.843 | 0.642 | 0.845 | |

| I feel like I am too busy to relax. | 0.74 | |||

| I often spend time in between too many things. | 0.81 | |||

| “Too much to do, too little time”; this phrase applies to me very much. | 0.85 | |||

| Perceived risk (second-order reflective) | 0.904 | 0.656 | 0.933 | |

| Perceived performance risk (first-order reflective) | 0.89 | 0.804 | 0.578 | 0.798 |

| The products advertised on the app are different from the actual ones. | 0.76 | |||

| The app’s recommended advertisements do not meet my expectations. | 0.78 | |||

| The advertisements prohibit my use of the app. | 0.74 | |||

| Perceived privacy risk (first-order reflective) | 0.83 | 0.920 | 0.792 | 0.922 |

| Private information obtained to display app advertisements may be misused. | 0.89 | |||

| My personal information gathered through app advertising may be distributed to unknown individuals or companies by merchants without my knowledge or approval. | 0.91 | |||

| Private information gathered through app advertising could be abused. | 0.87 | |||

| Perceived time risk (first-order reflective) | 0.90 | 0.878 | 0.706 | 0.877 |

| Returning or replacing goods will take longer because the products advertised in the app do not meet my expectations. | 0.82 | |||

| App advertising disrupts my time. | 0.86 | |||

| It takes a long time to choose and compare app ads. | 0.84 | |||

| Perceived freedom risk (first-order reflective) | 0.64 | 0.884 | 0.717 | 0.853 |

| App advertisements attempt to make decisions for me. | 0.82 | |||

| Ads in apps restrict my freedom of choice. | 0.85 | |||

| App advertisements take away my control. | 0.87 | |||

| Perceived psychology risk (first-order reflective) | 0.76 | 0.852 | 0.658 | 0.843 |

| App ads might be an insult to intelligence. | 0.75 | |||

| App advertisements can be annoying. | 0.85 | |||

| App advertisements make me unhappy. | 0.83 | |||

| Cognitive avoidance (first-order reflective) | 0.831 | 0.622 | 0.824 | |

| I purposefully redirect my attention away from the app advertisements. | 0.84 | |||

| I purposefully ignore the app’s advertisements. | 0.81 | |||

| Even if the ads on the app catch my attention, I do not click on them. | 0.71 | |||

| Behavioral avoidance (first-order reflective) | 0.876 | 0.638 | 0.873 | |

| I scroll up or down the page to avoid the ads when using the app. | 0.82 | |||

| When using the app, I take the opportunity to do something else when I encounter an ad. | 0.74 | |||

| I will click to skip or close the ads when using the app. | 0.86 | |||

| When I encounter an ad on an app, I mute the ad. | 0.77 | |||

| Mechanical avoidance (first-order reflective) | 0.873 | 0.697 | 0.873 | |

| I have installed ad blocker(s) to avoid ads in the app. | 0.87 | |||

| To avoid ads in the app, I set up ad blocking. | 0.87 | |||

| To avoid ads in the app, I choose software (platform) that can block ads. | 0.76 |

| Construct | Mean | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Risk attitude | 5.34 | 1.20 | 0.80 | |||||||||

| 2 | Time pressure | 4.72 | 1.30 | 0.42 | 0.80 | ||||||||

| 3 | Perceived performance risk | 4.90 | 1.20 | 0.36 | 0.41 | 0.76 | |||||||

| 4 | Perceived privacy risk | 5.04 | 1.42 | 0.45 | 0.45 | 0.62 | 0.89 | ||||||

| 5 | Perceived time risk | 5.05 | 1.30 | 0.42 | 0.47 | 0.72 | 0.66 | 0.84 | |||||

| 6 | Perceived psychology risk | 4.85 | 1.40 | 0.31 | 0.38 | 0.57 | 0.63 | 0.50 | 0.81 | ||||

| 7 | Perceived freedom risk | 4.49 | 1.46 | 0.27 | 0.34 | 0.42 | 0.52 | 0.49 | 0.60 | 0.85 | |||

| 8 | Cognitive avoidance | 5.00 | 1.28 | 0.44 | 0.47 | 0.63 | 0.58 | 0.68 | 0.49 | 0.44 | 0.79 | ||

| 9 | Behavioral avoidance | 5.24 | 1.26 | 0.51 | 0.49 | 0.57 | 0.59 | 0.69 | 0.45 | 0.39 | 0.75 | 0.80 | |

| 10 | Mechanical avoidance | 4.70 | 1.50 | 0.26 | 0.48 | 0.40 | 0.38 | 0.49 | 0.34 | 0.36 | 0.53 | 0.59 | 0.83 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Cao, N.; Isa, N.M.; Perumal, S. Effects of Risk Attitude and Time Pressure on the Perceived Risk and Avoidance of Mobile App Advertising among Chinese Generation Z Consumers. Sustainability 2023, 15, 11547. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151511547

Cao N, Isa NM, Perumal S. Effects of Risk Attitude and Time Pressure on the Perceived Risk and Avoidance of Mobile App Advertising among Chinese Generation Z Consumers. Sustainability. 2023; 15(15):11547. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151511547

Chicago/Turabian StyleCao, Ningyan, Normalisa Md Isa, and Selvan Perumal. 2023. "Effects of Risk Attitude and Time Pressure on the Perceived Risk and Avoidance of Mobile App Advertising among Chinese Generation Z Consumers" Sustainability 15, no. 15: 11547. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151511547

APA StyleCao, N., Isa, N. M., & Perumal, S. (2023). Effects of Risk Attitude and Time Pressure on the Perceived Risk and Avoidance of Mobile App Advertising among Chinese Generation Z Consumers. Sustainability, 15(15), 11547. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151511547