3. Review of the Literature

The author of Ref. [

19] defined participatory development as a practice through which stake-holders effect impactful and shared control over development initiatives, while also keeping in mind their individual development. In the context of the Indian Panchayati Raj, participatory development is crucial, as it aims to ensure people’s participation in the developmental process. The employment of recent technologies, including social media, is imperative in the process of participatory development.

The available literature emphasizes that social media has been extensively used for political campaigns and communications, and it has been established as an effective tool [

20,

21,

22,

23]. Although there is a paucity of academic work on social-media-enhanced political participation and its role in participatory development in the Indian context, evidence from around the globe on the efficacy of social media is available.

3.1. Sense of Platform and Social Participation

Sense of platform refers to the users’ subjective perceptions and attitudes toward a social media platform or online community, including emotional connection and belonging. Social participation involves active engagement in various online activities, like posting, commenting, and interacting. The sense of platform significantly influences user engagement and willingness to participate, contributing to a vibrant digital community. Recognizing this interplay is vital for designers and researchers to create engaging and user-friendly online spaces that enrich the users’ digital experiences. Social media can be viewed as socio-technical ventures that influence user engagement and provide participation platforms that allow for collaborative value-sharing and platform intervention.

The author of Ref. [

24] argued, using evidence from Nigeria, that community mobilization and development is almost impossible in the absence of social media. In Ref. [

25], the author reported that social media has a dynamic role in catalyzing development and social action. Similarly, the author of Ref. [

26] argued that social media can play a potential role in the community development and enhancement of social capital that ICT could not achieve. Another study using network analysis [

27] indicated that social media has brought positive results to the health and social interaction of the community.

It has been argued that, in the changing times of technology, social media has become imperative for development [

28]. The author of Ref. [

29] showed that social networks can potentially influence the proactive engagement of the community, which further results in the developmental benefits and strengthening of social capital. Another study reporting the ground realities indicated that the public use of social media would result in better collaboration between citizens and the authorities, which further results in citizen participation in public affairs [

30]. Evidence points towards improved public participation and heightened decision-making in urban planning through social media use [

31].

Access to social media and broadband networks has been found to be influential in rural community participation [

32]. The potentiality of social media in highlighting social problems through the active involvement of the people was also evidenced in [

33]. In their paper, the authors of Ref. [

34] reported that social media has a substantial role in initiating community action in the spheres of politics, democracy, neighborhood, and social support, thus aiding its public value through efficiency, effectiveness, and social value, which were empirically validated through the cross constructs of cost, time, convenience, personalization, communication, information retrieval, trust, well-informedness, and participation in decision-making [

35]. In the process of development, especially in the democratic framework, the role of social media in public service is inevitable. Its role in articulating dissent in democracies has also been established [

36].

The Indian government’s Digital India initiative was launched to achieve the objectives of education and information for all, along with a leadership structure for socially desirable outcomes [

37]. This, then, could be construed as the public value that could be obtained from the use of social media by EWRs.

Ref. [

38]’s version of the technology acceptance model attributed user adoption of a new technology to causes such as the perceived ease of use, perceived usefulness, and the intention to use the technology [

39].

Rural Indian society has a collectivist orientation, as defined by [

40], which shapes the individual, who then adopts the standards and ideologies promoted by his/her reference groups. How, then, does the use of social media by EWRs in a collectivist society such as India, where the activities of the individual are influenced by the views of one’s family, friends, and other broader affiliated social networks in the ecosystem, have policy implications for community engagement for furthering participatory development?

This paper attempts to study the factors related to the acceptance and usage of social media by the EWRs in India leading to the usage behavior and public value accrued from it for participatory communication and engagement with their community. The research aims to find out if Gram Panchayat women representatives’ social-media-enabled networked connections play a significant and important role in their rural development through enhancing involvement and representation via social media in the state of Karnataka.

In the context of elected women representatives using social media for participatory development communication, it is important to examine the relationship between sense of platform and social participation. While social media platforms offer a range of opportunities for participatory development communication, it is unclear whether a sense of platform has a positive impact on social participation.

Previous research has explored the influence of social media content on attitudes towards environmental-sustainability-knowledge dissemination [

41,

42]. However, research specifically examining the relationship between sense of platform and participatory community knowledge dissemination among elected women representatives in the context of development communication is limited.

The null hypothesis proposed for this study is that a sense of platform has no positive impact on social participation. Future research in this area should seek to examine the relationship between sense of platform and social participation, exploring the potential factors that may influence this relationship.

H01. Sense of platform has no positive impact on social participation.

3.2. Safety and Security and Social Participation

One of the main concerns associated with social media use is the privacy and security of personal data [

43]. Social media platforms are known to collect a large amount of personal data from their users, including their location, interests, and search history. This information can be used by third-party advertisers and hackers for malicious purposes, such as identity theft or targeted advertising. To address this issue, social media platforms have implemented various security measures, such as two-factor authentication, encryption, and data protection laws. However, users also have a responsibility to protect their own data by using strong passwords, avoiding sharing personal information, and reviewing privacy settings regularly.

Another major concern associated with social media use is cyberbullying and online harassment. These negative behaviors can have a significant impact on the mental health and well-being of victims, and can also discourage users from participating in online communities [

44]. Social media platforms have implemented various measures to combat cyberbullying and online harassment, such as content moderation, reporting systems, and blocking features. However, these measures are not always effective, and users may need to take additional steps to protect themselves, such as blocking or reporting abusive users.

Social media platforms have also been criticized for their role in spreading fake news and misinformation, which can have serious consequences for public health and safety. Misinformation can lead to confusion and mistrust, and can also undermine public confidence in institutions and organizations [

45]. To address this issue, social media platforms have implemented various measures to combat fake news and misinformation, such as fact-checking, content moderation, and warning labels. However, these measures are not always effective, and users also have a responsibility to verify information before sharing it.

Social media has the potential to play a significant role in community-based protection by enabling UNHCR and other stakeholders to engage with refugees and host communities, disseminate information, and gather feedback. However, social media also presents several challenges that must be addressed to ensure the responsible use of these platforms [

46].

Based on the above literature review, the researcher proposes the null hypothesis that safety and security have no positive impact on social participation. This hypothesis implies that the safety and security concerns related to social media use do not affect the level of social participation among women representatives who use social media for participatory development communication.

H02. Safety and security have no positive impact on social participation.

3.3. Social Equity and Social Participation

Social equity refers to fairness, justice, and equality in the distribution of resources and opportunities in society. In the context of women using social media for participatory development, social equity may have an impact on their level of social participation. However, there is limited research on the relationship between social equity and social participation among women using social media for participatory development.

One study found that while social media has been effective in creating a space for women’s voices to be heard, it has not necessarily led to increased participation in decision-making processes [

47]. Another study found that women’s participation in social media can be limited by social norms and gender biases that prevent them from fully engaging in online discussions [

48].

Therefore, it is unclear whether social equity has a positive impact on social participation among women using social media for participatory development. As such, the null hypothesis is retained:

H03. Social equity has no positive impact on social participation.

3.4. Social Interaction and Social Participation

Social interaction and participation are important aspects of participatory development communication for women using social media. Research has shown that older individuals tend to have smaller social networks due to changes in their life cycle stage, such as retirement, age-related losses, and mobility limitations, which can lead to feelings of loneliness and social isolation [

49]. Additionally, iGen adolescents in the 2010s have spent less time engaging in face-to-face social interaction with peers and more time on digital media, which has led to time displacement at the cohort level [

50]. However, the null hypothesis states that social interaction has no positive impact on social participation for women using social media for participatory development communication.

H04. Social interaction has no positive impact on social participation.

3.5. Social Participation and Social Satisfaction

Social sustainability is an essential component of sustainable development, yet there is no universally accepted definition, conceptualization, or operationalization of urban social sustainability [

51,

52]. To fill this gap, researchers have operationalized the USS scale as a comprehensive measurement model for analyzing social sustainability at the neighborhood level [

53]. However, little research has been conducted on how social media affects younger generations’ consumption habits, particularly with regard to China [

54]. It has been found that subjective norms and perceived green values affect attitudes toward the environment and play a significant mediating role in raising customer intentions to purchase environmentally friendly goods [

55]. Furthermore, Twitter has a twofold higher chance than other social media platforms of boosting client involvement through happiness and positive feelings. The study finds that customer interaction has significant value for businesses, having a direct impact on firm performance, behavioral intention, and word-of-mouth. Additionally, hedonic consumption results in consumer engagement that impacts firm performance approximately three times more than utilitarian consumption. Contrary to popular belief, word-of-mouth marketing neither enhances nor mitigates the benefits of consumer engagement on a company’s performance [

56]. Therefore, the null hypothesis is proposed (

Figure 1).

H05. Social participation has no positive impact on social satisfaction.

4. Methods and Empirical Testing

This study is based on an experimental design that used a pre-structured questionnaire. We borrowed the items and constructs from the study by [

57] and further edited them as per the requirements of this study. The questionnaire was designed to investigate the impact of the sense of platform, safety and security, social equity, and social interaction on social participation, as well as the impact of social participation on social satisfaction. Furthermore, it aimed to identify their impact on a sustainable community by measuring the relationship between social participation and social satisfaction. All the items used to measure the constructs were taken from previous studies discussed in the literature review when framing hypotheses.

A proper sampling strategy was required as it is not always possible to collect data from every unit of the population [

58]. Hence, we needed an appropriate sample size to obtain valid conclusions from the research findings. To estimate the sample size for the study, power analysis was conducted using G*Power software (Version 3.1.9.7), following the recommended settings suggested by [

59].

The power analysis and a number of studies revealed that 200 respondents were sufficient to apply SEM (structural equation modeling) as the model has a maximum of 4 predictors [

60]. Some authors from recent studies have recommended using power analysis for sample size calculation purposes [

61,

62].

A purposive sampling method was used as only elected Panchayat female members were consulted for the study. Consent was implied by the submission of the completed anonymous survey. Furthermore, the questionnaire clearly gave the general information about the study objectives. Participation was entirely voluntary, and respondents could withdraw at any time. Respondents were assured that their answers would be anonymous and treated confidentially.

5. Data Analysis and Results

Data Analysis: The quantitative approach was used to answer the research objectives. For statistical analysis, SPSS software version 26 was used for descriptive analysis, and AMOS was used for structural equation modeling.

Results: The data were collected from 200 elected women representatives. Some 12.5% of the respondents were between 20 and 30 years old, 24% of the respondents were between 30 and 40 years old, approximately 23% of the respondents were between 40 and 50 years old, 25% of the respondents were in the age category of 50 to 60 years, and 15% of the respondents were over 60 years old. In terms of the highest education level, 33% of the women were 12th pass outs, 30% were graduates, 20% had a Master’s degree, and 17% of women had completed professional courses (

Figure 2).

In terms of family size, 9.5% of women had two members in their family, 13% had three members, 18.5% had four members, and approximately 28% of women had five members, while 31% of women had more than five members in their family. Regarding household annual income, 15.5% of women had an income below INR 50,000, 17% earned between INR 50,000 and 200,000, 24% between INR 20,000 and 500,000, 19% between INR 500,000 and 1,000,000, and 24.5% of women had an annual income of more than INR 1,000,000 (

Figure 3).

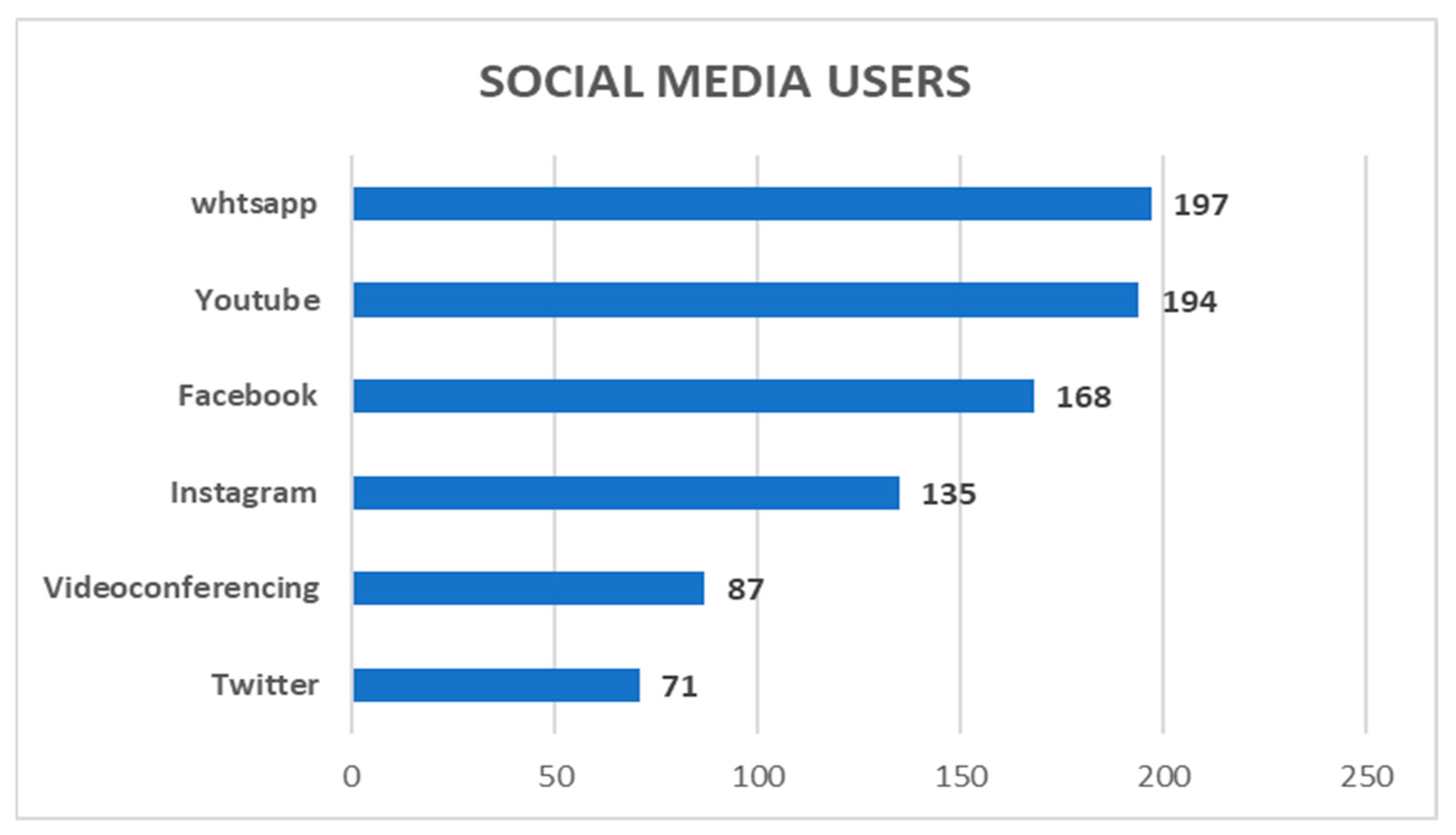

In terms of Panchayat division, 27.5% of elected women belonged to the Belagavi division, 24% were from the Bengaluru division, 24.5% were from the Gulbarga division, and 24% of women respondents belonged to the Mysuru division. The most commonly used social media sites by respondents were Twitter (35.5%), Videoconferencing (43.5%), Instagram (67.5%), Facebook (84%), YouTube (97%), and WhatsApp (98.5%) (SPSS version 26) (

Figure 4).

We applied SEM for data analysis, including confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) for the measurement model analysis. CFA was used to test the compatibility of the research and determine whether the data fit the hypothesized measurement model. To assess scale reliability, we examined the Cronbach’s alpha value for each construct used in the scale, which was found to be above 0.7 for each construct.

Table 1 presents the final reliability measurement, means, standard deviations, and factor loadings of the instrument. All Cronbach’s alpha values ranged between 0.75 and 0.860, indicating the constructs’ reliability. All constructed items were measured correctly.

The results below indicate that all factor loading (FL) values exceeded the designated threshold for establishing convergent validity, with significant loadings ranging between 0.653 and 0.845. However, in the context of Indian Elected Women Representatives (EWRs) of Panchayati Raj Institutions using social media for participatory development communication purposes, two factor loadings of the variable “Social Interaction” (social interaction 3 and social interaction 4) and two factor loadings of the variable “Social Participation” (social participation 4 and social participation 5) were found to be insignificant, with values below 0.5. Consequently, these items were excluded from the structural equation modeling (SEM) path diagram. The nature of social interaction and social participation in the Indian context may differ from conventional measures, making it challenging to capture these concepts accurately through the selected items. The specific sample of EWRs might have unique characteristics that impact their perception of social interaction and social participation, making some items less relevant or meaningful to them. Considering these factors, the decision to remove these items from the SEM path diagram was appropriate to ensure the validity and robustness of the analysis in understanding the relationship between social media use and participatory development communication among Indian EWRs. The mean values of all the items ranged between 3.39 and 3.78 on a five-point Likert scale, where 1 represents “strongly disagree” and 5 represents “strongly agree”.

In addition, the average variance extracted (AVE) values exceeded the threshold value of 0.5, ranging from 0.51 to 0.62 (

Table 2). Furthermore, the composite reliability (CR) values ranged from 0.754 to 0.892. Therefore, the study concludes that all the items in the measurement model were internally consistent, and convergent reliability was established.

Table 3 presents a summary of the SEM model. Among the various model fit indices, the Chi-square (CMIN/DF) value was 2.081, which was significant with a

p-value of 0.000. If the values of GFI, IFI, TLI, and CFI were above 0.9, the model was considered to be a good fit. In the present study, the values of GFI, IFI, TLI, and CFI were 0.836, 0.88, 0.858, and 0.89, respectively, which were close to 0.9. Therefore, they all indicated good fitness for the proposed model. Moreover, if the value of RMSEA was less than 0.05, it would indicate a good model fit. For the proposed model, the RMSEA value was 0.052, which also indicates a good fit (

Figure 5).

5.1. Structural Model Analysis and Hypotheses Testing

The regression weight between the sense of participation and social participation was 0.44, safety and security and social participation was 0.09, social equity and social participation was 0.41, and social interaction and social participation was 0.18. According to the

p-value, the relationship between safety and security and social participation, as well as the relationship between social interaction and social participation, were not statistically significant. However, the relationship between sense of participation and social participation was statistically significant. The correlation between social equity and social participation was also statistically significant (

p = 0.012). Additionally, the correlation between social participation and social satisfaction was statistically significant (

p = 0.029). The correlation between sense of participation and social participation was also statistically significant (

p < 0.001) (

Table 4).

5.2. Hypothesis Testing Results

Research has found that social participation, which involves engaging in activities with others, has numerous benefits. These include improved mental and physical health, increased social support, and enhanced social capital. Social capital refers to the resources individuals or groups have access to through their social connections. These resources, such as information, opportunities, and social support, can help individuals achieve personal or collective goals. Social networks play a crucial role in forming social capital and providing opportunities for social participation. Online platforms have been shown to facilitate the formation of social networks, thus offering individuals social support and opportunities for participation.

H01. The presence of a sense of platform does not lead to increased social participation (rejected).

For instance, Ref. [

63] found a positive association between the sense of platform among the residents of a Japanese community and their participation in local community events. Similarly, our study found that the sense of platform in online communities was positively linked to social capital, which, in turn, positively influenced offline participation in civic activities. Additionally, Ref. [

64] discovered a positive association between the sense of virtual community in South Korea and both social capital and civic participation.

H02. Safety and security do not contribute positively to social participation (rejected).

Research suggests that safety and security play an important role in shaping social behavior and can have a positive impact on social participation. Recent studies have shown that safety and security are significant factors in promoting social participation [

65]. Ref. [

66] discovered that perceived safety in the neighborhood was positively correlated with social participation among older Korean immigrants in the United States. In a study involving Chinese older adults, Ref. [

67] found that perceptions of neighborhood safety were positively linked to social participation. These findings indicate that safety and security may enhance social participation by fostering a sense of trust and community among individuals.

H03. Social equity does not have a favorable impact on social participation (rejected).

This study revealed a positive association between social equity and social participation among older adults. The findings indicated that higher levels of social equity were linked to increased engagement in community activities and volunteer work. Furthermore, it was observed that social equity had a positive influence on social participation, and this relationship was partially mediated by social capital. The promotion of social equity can contribute to the enhancement of social capital by ensuring more equitable access to resources and opportunities. This, in turn, can foster greater participation in social activities. In line with these findings, Ref. [

68] identified a positive association between social equity and social participation, with social capital serving as a mediating factor.

H04. Social interaction does not significantly influence social participation (accepted).

Social interaction is an important aspect of human life, particularly for older adults who may face increased feelings of loneliness and social isolation as they age. Initially, it was believed that social interaction had no significant impact on social participation among older adults. However, recent research has shed new light on this topic, revealing some interesting nuances. One study conducted of older adults who experienced loneliness found a negative association between social interaction and social participation [

69]. This suggests that, in some cases, individuals who engage in social interactions may still struggle to actively participate in social activities. The reasons behind this apparent contradiction may be complex and multifaceted. The same study also discovered that while social interaction alone may not guarantee enhanced social participation, it does play a crucial role in mitigating the negative impact of loneliness on social engagement. In essence, even if social interaction might not directly increase social participation, it acts as a buffer against the detrimental effects of loneliness, encouraging individuals to become more involved in social activities. The relationship between social interaction and social participation appears to be influenced by other factors, such as the presence of chronic conditions. Another research study demonstrated that individuals with chronic conditions can experience a positive influence on social participation through increased social interaction [

70]. For these individuals, engaging in social interactions seems to facilitate their active involvement in social activities, which can be particularly beneficial for their overall well-being and quality of life. The connection between social interaction and social participation appears to be more pronounced among individuals with higher levels of social support. This implies that the availability of a strong support network might enhance the positive impact of social interaction on social participation. In contrast, individuals with limited social support may find it more challenging to translate their social interactions into increased social engagement. While it was initially believed that social interaction might not have a positive impact on social participation, recent research has shown that its influence is more nuanced. Social interaction alone may not directly lead to heightened social participation, but it does play a vital role in reducing the negative effects of loneliness and can be particularly beneficial for individuals with chronic conditions. The level of social support available to individuals can further modulate the relationship between social interaction and social participation. As the dynamics of social interaction and its effects on social engagement are complex and context-dependent, further research in this area is warranted to gain a deeper understanding and develop targeted interventions that promote social well-being among different populations.

H05. Social participation does not result in increased social satisfaction (rejected).

The study revealed that engaging in social activities can assist older adults in maintaining social connections, ultimately enhancing their overall life satisfaction. Additionally, it was found that social participation is a significant predictor of social satisfaction among older adults [

71]. Participating in social activities fosters a sense of belonging and social identity, which subsequently contributes to increased social satisfaction.

6. Discussion

The discussion regarding the impact of safety and security on social participation is crucial as it provides insights into how to promote social participation in communities. Research suggests that safety and security have a significant influence on enabling and encouraging social participation, especially among EWRs engaged in community participatory development activities. The aforementioned studies indicate that individuals who perceive social media platforms as safe are more likely to engage in social activities, participate in community events, and engage in civic activities online. This is noteworthy since social participation has been linked to increased social satisfaction.

Promoting safety and security in communication interactions through social media can help address social isolation within communities, which has been identified as a significant concern [

72]. By creating safe and secure environments that foster social interaction and participation, individuals are more likely to form social connections, engage in community activities, and experience a greater sense of belonging and social satisfaction. Promoting safety and security in communication through social media may be an effective approach for encouraging social participation in communities. Additionally, efforts to enhance community involvement and participation in decision-making processes through social media can promote social connections and relationships. Addressing social isolation and loneliness can serve as an important strategy for promoting social participation.

Promoting safety and security in communication through social media carries important implications for fostering social participation, particularly among vulnerable populations. In conclusion, the evidence suggests that safety and security play a positive role in social participation, and endeavors to promote safety and security in communities may have significant implications for enhancing social participation, especially among vulnerable populations.

6.1. Theoretical Contribution

The theoretical contribution of research that explores the impact of safety and security on social participation lies in its ability to expand our understanding of the complex interplay between individual and environmental factors that shape social behavior. By examining the role of safety and security in promoting social participation, this research contributes to our understanding of how the online social environment can influence individual behavior and participatory communication. From a social psychological perspective, this research can help us understand the mechanisms underlying the relationship between safety and security and social participation. For example, research has suggested that feelings of safety and security can increase an individual’s sense of social trust and connectedness, which may in turn encourage them to participate in social activities.

This research can help inform public health interventions aimed at promoting social participation and reducing social isolation among vulnerable groups. By identifying the role of safety and security in promoting social participation, interventions can be designed to address these environmental factors and create social environments that are conducive to social participation [

73]. Research on the impact of safety and security on social participation has important theoretical implications for our understanding of the role of the social media platforms in shaping social behavior and well-being. By identifying the factors that promote social media to enhance community participation, this research can help inform interventions aimed at promoting social connection and reducing social isolation and loneliness. In addition to the social psychological perspective and public health interventions, research on the impact of safety and security on social participation also has broader theoretical implications for sociology and urban studies. This research highlights the importance of understanding the physical and social environment as a key factor in shaping individual behavior and social outcomes.

From a sociological perspective, this research can help us understand how the social context and environment influence social participation. For example, social disorganization theory suggests that high levels of crime and disorder can disrupt social networks and social institutions, leading to reduced social participation and community cohesion [

74]. In contrast, the social capital theory suggests that social networks and trust can promote social participation and collective action. Therefore, understanding the role of safety and security in shaping social networks and community cohesion can inform our understanding of how social structures and institutions influence social behavior.

The theoretical contribution of research on the impact of safety and security on social participation is multidisciplinary, with implications for social psychology, sociology, public health, and urban studies. By identifying the factors that promote social participation and community well-being, this research can inform interventions and policies aimed at improving social outcomes and enhancing the quality of life in communities.

6.2. Managerial Implications

The study exploring the role of social media in creating a sustainable community has several important managerial implications for community leaders and organizations interested in promoting sustainable communities. Firstly, the study highlights the important role that social media can play in facilitating the creation and maintenance of sustainable communities. Community leaders and organizations should consider utilizing social media platforms as a means of communicating with community members and promoting sustainable practices. Secondly, community leaders should be mindful of the potential barriers to social media use among certain segments of the population. Specifically, older adults and individuals with lower levels of education may be less likely to use social media, and alternative means of communication should be considered when targeting these groups. Thirdly, community leaders should consider the potential risks and challenges associated with social media use, such as the spread of misinformation and the potential for social media to perpetuate existing inequalities. As such, community leaders should work to establish guidelines and best practices for social media use in the context of community sustainability.

The study highlights the potential benefits and challenges associated with social media use in promoting community sustainability. As such, community leaders and organizations should carefully consider the findings of this study when developing strategies for promoting sustainable communities.

6.3. Limitations and Future Research

While research on the impact of safety and security on social participation has important theoretical implications, there are also some limitations to consider. For example, the research may not capture the full complexity of the relationship between safety and security and social participation, as there may be other individual and environmental factors that influence this relationship. Additionally, the research may not be generalizable to all populations or contexts, as different cultural, social, and economic factors may influence the relationship between safety and security and social participation. Future research could address these limitations by exploring the relationship between safety and security and social participation in different populations and contexts, and by examining the underlying mechanisms and moderators of this relationship. For example, future research could explore how cultural factors may influence the relationship between safety and security and social participation, or how individual differences in personality, social support, or other factors may moderate this relationship.

Future research could explore the impact of safety and security on other outcomes beyond social participation, such as mental health, physical health, and quality of life. By examining the broader impacts of safety and security on individual well-being and social outcomes, this research can inform interventions and policies aimed at improving community well-being. Another area of potential future research is the impact of safety and security on different types of social participation. For example, research could explore the impact of safety and security on online social participation and virtual communities, as these have become increasingly important in the digital age. Additionally, research could explore the impact of safety and security on different forms of social participation, such as volunteering, political engagement, or sports and leisure activities.

Further research could explore the impact of safety and security on social participation over time, and how changes in safety and security may influence social behavior and outcomes. For example, research could examine how changes in crime rates, natural disasters, or political instability may impact social participation and community well-being. By taking a longitudinal approach, this research could provide important insights into the long-term impact of safety and security on social outcomes, and inform interventions and policies aimed at promoting community resilience and well-being.

While research on the impact of safety and security on social participation has made important contributions to our understanding of the role of the environment in shaping social behavior, there is still much to be explored in this area. Future research could help address the limitations of existing research and inform interventions and policies aimed at improving social outcomes and enhancing community well-being.

6.4. Conclusions

This study titled “Social Media-enabled Sustainable Communities: A case of Indian Elected Women Representatives (EWRs)” examined the impact of various factors on social participation among older adults. The hypotheses related to the sense of platform, safety and security, social equity, social interaction, and social participation were tested and yielded interesting findings.

The results indicated that the sense of platform in online communities positively influenced social capital and offline participation in civic activities. This aligns with previous research highlighting the role of social networks facilitated by online platforms in promoting social participation. Safety and security were also found to have a positive impact on social participation, fostering trust and a sense of community among individuals. This emphasizes the importance of creating safe and secure environments to encourage social connections and engagement in community activities.

Social equity was positively associated with social participation, with higher levels of social equity leading to increased engagement in community activities and volunteer work. The relationship between social equity and social participation was partially mediated by social capital, highlighting the role of equitable access to resources and opportunities in fostering greater participation.

Social interaction was found to be negatively associated with social participation among older adults experiencing loneliness. However, social interaction was also identified as a mitigating factor, helping to alleviate the negative impact of loneliness on social participation. Additionally, social interaction was shown to have a positive impact on social participation among individuals with chronic conditions.

Social participation was found to be a significant predictor of social satisfaction among older adults, emphasizing the importance of engaging in social activities for maintaining social connections and enhancing overall life satisfaction.

The findings of this study contribute to the understanding of the factors influencing social participation among older adults. The results highlight the significance of the sense of platform, safety and security, social equity, social interaction, and social participation in promoting social connections, community engagement, and social satisfaction. Efforts to promote safety and security in communication through social media can play a crucial role in encouraging social participation, particularly among vulnerable populations. Addressing social isolation and loneliness should be considered important strategies for fostering social participation in communities. These insights can inform the development of interventions and policies aimed at enhancing social participation and well-being among older adults and other community members.