Abstract

With the development of the social economy, people’s living standards continue to improve, and the consumer demand for environmentally friendly products also increases. At the same time, many businesses have an inaccurate grasp of consumers’ consumption concept of environmentally friendly products, and there are many problems of imbalance between supply and demand. In order to improve consumers’ consumption concepts of environmentally friendly goods and maintain a balance between supply and demand in the market for environmentally friendly goods, this article takes energy-saving appliances as an example to analyze their product consumption models and trend predictions. Based on quantifying changes in residents’ consumption, two consumption models are proposed to address consumption concepts and supply and demand issues and to analyze residents’ consumption of environmentally friendly goods. The conjoint analysis method is to score and sort the products according to the willingness of consumers to a certain product, and finally analyze consumers’ preference for environmentally friendly products according to consumption behavior. The article divides the discrete choice model into four small models. Different analyses are carried out according to the consumption in different states, and from the perspective of consumers, the consumption preferences of consumers when purchasing commodities are analyzed to determine the main factors that affect consumers’ purchase of environmentally friendly commodities. In the experimental part of the article, two consumption models are used to analyze consumers’ consumption preference for environmental protection products, the prediction accuracy of consumption preference, and consumption desire. The experimental results found that consumers of different age groups have increased their desire to purchase environmentally friendly products under the stimulation of the consumption model. Under the stimulation of the discrete choice model, the consumption of residents under the age of 18 increased by 23% compared with the original. Compared with the conjoint analysis method, the discrete choice model is 12% more effective in stimulating consumption desire, and the stimulation effect is better.

1. Introduction

Under the premise of actively advocating green environmental protection in society, residents’ demand for environmentally friendly goods is increasing [,]. Taking energy-saving appliances as an example, they have gained new market opportunities with the deepening of environmental protection concepts [,]. However, with the increase in consumer demand, many energy-saving electrical products have encountered problems such as low supply efficiency and quality and asymmetric product supply and demand during the consumption process, resulting in a sharp decline in consumer satisfaction in this regard. This not only affects the health consumption of residents but also hinders the sustainable development of environmentally friendly product manufacturing enterprises. Therefore, an in-depth analysis of residents’ consumption models and trend predictions for environmentally friendly products is of great value in helping residents correctly grasp consumption concepts and maintain a balance between supply and demand in the environmental protection product market. Consumer preference is a personalized preference that reflects the degree of consumer preference for different products and services, which is an important factor affecting market demand. Building a consumption model based on consumer preference analysis is not only beneficial for businesses to develop marketing strategies and product supply based on consumer preferences but also for mobilizing residents’ awareness of environmental goods consumption, which has important practical significance in enhancing consumers’ desire to purchase environmental goods.

In recent years, consumers’ demand for environmentally friendly products has gradually increased. Kumar [] explored the main factors influencing consumer behavior toward green electronics. Ajzen’s (1991) theoretical framework of planned behavior is used, which is widely used not only in the field of psychology but also in many other fields of the social sciences to explain and predict the behavior of individuals. They employed a descriptive research design (cross-sectional), and all four constructs of model attitudes, subjective norms, perceived behavioral control, and behavioral intentions were measured by three statements on a seven-point Likert scale. The experimental results confirm that the theory of planned behavior can explain the determinants of consumers’ behavior toward green electronic products, and their article provides some important implications for marketers engaged in the marketing of green products. Wysokinska [] reviewed multinational regulations (global and European) in the field of environmental protection and circular economy. Regarding the World Trade Organization, attention should be paid to the impact of trade liberalization on environmental goods and services, as well as environmentally sound technologies. Sustainable development, first and foremost, means protecting the natural environment and reducing the economic sector’s excessive dependence on natural resources, including primary raw materials. This means that a new resource-saving development model needs to be implemented based on the circular economy principles proposed by multinational organizations over the years. In the CE model, the use of natural resources is minimized, and when a product reaches its useful life, it is reused to create additional new value. This can lead to significant economic benefits, contributing to new production methods and new innovative products, growth, and job creation. Pan et al. [] believed that the choice of environmental supervision tools determines the effect of environmental protection. Governments can give regulated companies complete discretion to act in their own interests, or they can create regulations that remove that discretion. According to the discretion left by the government to the regulated enterprises, the regulatory tools can be divided into pure government regulation, meta-regulation, self-regulation, and unrestricted freedom.

Consumer preference directly affects consumers’ choice of certain commodities. Cheng and Ho [] believed that consumers’ concerns about environmental protection had affected their consumption. People in Asian countries usually choose two-wheeled scooters to commute to and from work because they are relatively cheap and convenient. While e-scooters enter the market with an emphasis on environmental responsibility, their market penetration remains low, and there is little research on the subject. Based on the theory of planned behavior, supplemented by environmental awareness variables in Taiwan, they explored the willingness of college students to use electric scooters. The results showed that environmental awareness had a significant impact on students’ attitudes, subjective norms, and perceived behavioral control. Attitude was the strongest predictor of intention to use an e-scooter. The research results provide guidance for enterprises and decision-makers to further improve the marketing strategy of electric scooters. Wenchao Wu et al. used an integrated assessment modeling framework consisting of a general equilibrium model (Asian-Pacific Integrated Model/Computable General Equilibrium) to estimate the maximum bioenergy potential under environmental protection policies (biodiversity and soil protection) and societal transformation measures from the demand and supply side (demand-side policy includes sustainable diet; supply-side policy includes advanced technology and trade openness for food) []. Millan and Mittal [] argue that the foundation of the luxury and identity markets goes beyond the traditional affluent consumer base, including an increasingly diverse consumer base. They developed a conceptual model of the psychological determinants of status-seeking through consumption. The model considers the effect of three general characteristics and one consumption-related consumer characteristic on status, meaning preference, which in turn influences consumer interest in a product. The hypothesized causal relationships are all supported. The effects of status attention, public self-awareness, and self-esteem on susceptibility to normative social influence (SNSI) and preference for status meaning (PSM) were significant and in the expected directions. In addition, the study found that SNSI had a significant positive effect on PSM. These two structures, in turn, have a significant positive impact on consumer interest in clothing. Conceptual models and Empirical evidence add to existing knowledge of the antecedents and consequences of identity consumption. Sun et al. [] believe that the regulatory orientation of consumers regulates this process. Specifically, consumers weigh adjustable and non-adjustable attributes differently depending on whether they are prevention or promotion-oriented. Results from four studies suggest that preventive consumers, who tend to analyze information at a more specific level, rely more on consistency attributes when evaluating both options. And promotional consumers, who tend to analyze information at a higher level, are more affected by inconsistency attributes. The scholars further show that the level of consumer awareness and the varying ease of processing these two types of attributes mediate the effect of regulatory orientation on the relative weights of alignable and non-alignable attributes and product evaluation. According to the study by Rozi F, rice, corn, cassava, and sweet potatoes—food items that are important sources of carbohydrates—are inelastic, meaning that changes in demand have no impact on their costs. The principal food source for the inhabitants is still rice []. In order to ascertain the preferences of the residents of the Hei River Basin in China with regard to the preservation, repair, and development of ecological systems and the services that go along with them, a survey study was conducted. For distance decay, the study combined a number of random parameter logit models. The study divided the study region into three distance-based groups: group I (within 25 km), group II (between 25 and 50 km), and group III (beyond 50 km). Data were obtained using a choice experiment approach. The results demonstrated the regional variability of the population, with higher readiness to pay for high-quality agricultural output and the lowest desire to pay for an oasis. The findings showed a complicated pattern of regional heterogeneity and suggested that further awareness campaigns, environmental education, and societal responsibility for environmental conservation were necessary []. Consumers’ willingness to pay more for meat and plant-based meat alternatives that are produced responsibly is studied by B Katare et al. We carried out an experimental auction with incentive compatibility in addition to randomized control research. Informational prods on the negative health and environmental effects of meat production and consumption made up the course of treatment []. Liu et al. [] believed that the conflict between the dual channels of fresh agricultural products is a focal problem that needs to be solved urgently. Based on consumer service preference, this paper verifies the effectiveness of the dual-channel supply chain three-stage game method in the integration and distribution of fresh agricultural products through case analysis. The research results have important guiding value for the dual-channel supply chain management of fresh agricultural product distribution resources integration. Kim Myung Ja et al. [] developed a consumer behavior theory framework using stimulus organic response theory, including real experiences, cognitive and emotional responses, and attachment. The results indicate that real experience has a significant impact on cognitive and emotional responses, indicating that real experience is an important factor in consumer behavior. In order to better understand environmentally sustainable consumption and promote environmentally responsible consumer behavior, Han Heesup [] provides a reasonable concept for environmentally sustainable consumer behavior and systematically reviews and prospects the theories established in tourism and environmental psychology (rational action theory, norm activation theory, Theory of planned behavior, goal-oriented behavior model, value belief norm theory). She also introduced the basic drivers of environmentally sustainable consumer behavior to achieve the universal goal of promoting environmentally friendly consumption and environmental sustainability. The above analysis of consumer preferences and consumption of environmentally friendly goods is relatively comprehensive, but it does not provide more specific guidance for residents’ consumption models and trend predictions based on actual development. In light of the above studies, the challenges can be shortly summarized as follows:

Lack of supply efficiency and product quality: Due to the growing customer demand for environmentally friendly items, many energy-saving electrical devices struggle to satisfy consumer demand while still maintaining high standards of quality. Consumer happiness suffers as a result, and businesses that provide environmentally responsible products struggle to grow. There is an imbalance between the supply and demand for environmentally friendly items during the consumption process. Variations in customer tastes and a mismatch between the items on the market and the desires of certain consumers are to blame for this imbalance. As a consequence, some customers could find it difficult to discover items that meet their needs, which could cause them to be dissatisfied and fall short of their environmental objectives. Consumer dissatisfaction decline: Consumer satisfaction has fallen precipitously as a result of problems with inefficient supply chains, worries about quality, and an imbalance between supply and demand. Unhappy customers would completely forgo their plans to buy eco-friendly items, which would impede the market’s expansion and deter further investments in environmentally friendly production. Impact on health consumption and sustainable development: The difficulties encountered in consuming environmentally friendly products have a negative impact on both consumer well-being and the long-term sustainability of businesses that produce such products. Maintaining residents’ health and enabling long-term growth and success of enterprises in the market for environmental protection products depends on striking a balance between supply and demand.

Considering these challenges, the goal of this article is to address the difficulties and problems associated with purchasing environmentally friendly goods from the market. Demand for eco-friendly products is rising as the social economy matures and people’s living conditions rise. However, many firms find it difficult to fully comprehend how consumers think about using these items, which creates an imbalance between supply and demand.

This article assumes that consumer preferences have a positive impact on residents’ consumption models and trend predictions of environmentally friendly goods. Two analytical models, namely the joint analysis method and the discrete choice model, are proposed for consumers’ purchasing behavior when purchasing environmentally friendly goods. In the experimental part of the article, the two models are analyzed in the analysis of consumers’ purchase of environmentally friendly products. First, the age group of environmental protection products was analyzed. The experiment found that consumers aged 26–40 accounted for 41.34%, and consumers aged 41–60 accounted for 24.62%. In the consumption of environmentally friendly products, consumers in the age group of 26–60 are the most representative. Analyzing the change in residents’ consumption desire under the conjoint analysis method and discrete choice model, it is found that the consumption desire of consumers under the age of 18 has increased by 35% in the discrete choice model. Using the conjoint analysis method and the discrete choice model to analyze the accuracy of consumers’ consumption preferences for environmental protection products, it is found that the accuracy of the discrete choice model is higher than that of the conjoint analysis method by 7%, 8%, and 6%, respectively. It shows that the discrete choice model has high accuracy. Under the influence of various factors, the analysis of residents’ purchasing trends of environmental protection products shows that under the discrete choice model, the purchasing trend of consumers is more obvious. From the research results, it can be seen that based on consumer preference theory, predicting the consumption model and trend of environmentally friendly goods for residents is not only beneficial for improving consumers’ consumption concepts of environmentally friendly goods but also for promoting the balanced development of market supply and demand. The salient feature of this article is the following:

- The article shows the market’s mismatch between supply and demand as well as customers’ misperceptions of what constitutes an environmentally friendly product. It recognizes the rising customer demand for environmentally friendly products but also that businesses are having trouble properly satisfying this need.

- Analysis of product consumption models: The article analyses product consumption models using the example of energy-saving appliances. It offers insights into how customers perceive and assess environmentally friendly items by examining their consumption habits and preferences.

- Two consumption models are proposed in the essay to handle supply and demand difficulties as well as consumption ideas. These approaches seek to increase customers’ knowledge of environmentally friendly products and preserve a balance between market supply and demand.

- Separation of the discrete choice model into four smaller models: To analyze consumption in various states, the paper separates the discrete choice model into four smaller models. This method enables a thorough investigation of consumer preferences and the variables influencing customers’ purchasing of environmentally friendly products.

- Age-related findings: According to the experimental findings, consumers of various age groups, especially those under 18, exhibit a greater willingness to buy environmentally friendly goods when motivated by the consumption model. The potential impact of focused interventions to change consumer behavior is shown by this study.

2. Residential Environmental Protection Commodity Consumption Model and Trend Prediction Method Based on Consumer Preference

2.1. Consumer Preferences

Consumer preference is determined by the utility brought to consumers by a product or service. Consumers will form a utility function for each product based on their own preferences, and the greater the utility, the greater the preference.

2.2. Joint Deconstruction Method

The joint analysis method is a multivariate statistical analysis method that quantitatively studies consumer choice preferences, used to estimate the relative importance and utility of product attributes that can be defined in detail []. The basic idea of the combined analysis method is to combine commodities with different attribute levels and make psychological judgments by customers. According to their wishes, the product combinations are scored and sorted, and then the value of each attribute level is allocated to customers by mathematical analysis. In order to maximize customer satisfaction, this article analyzes and studies customer choices.

Portfolio analysis can not only analyze the importance of quantitative attributes such as price but also analyze the importance of qualitative attributes such as brand. The data collection process is straightforward, and users only need to consider their priorities, not the size of their preferences. Linkage analysis requires customers to exchange between different attributes rather than directly asking customers about the desired level and importance of attributes. Using the conjoint analysis method, consumers analyze the preference degree of a certain commodity and establish a basic preference model [].

(1) Preferred vector model

In the vector model, assuming that each product has attributes and each attribute has levels, then for a given product or service in the consumption process, the vector model can be used to represent the utility of the product, and it can be got:

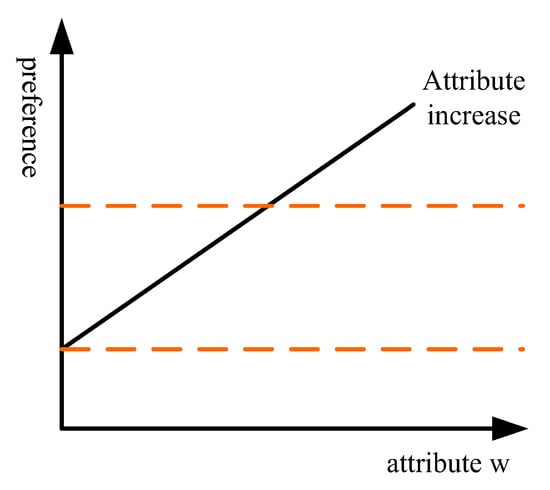

In a linear vector model, as the number of attributes of a product increases, consumers’ preference for that product also increases [], as shown in Figure 1:

Figure 1.

Vector model, the vertical lines shows the range of consumers’ preferences.

(2) Ideal point model

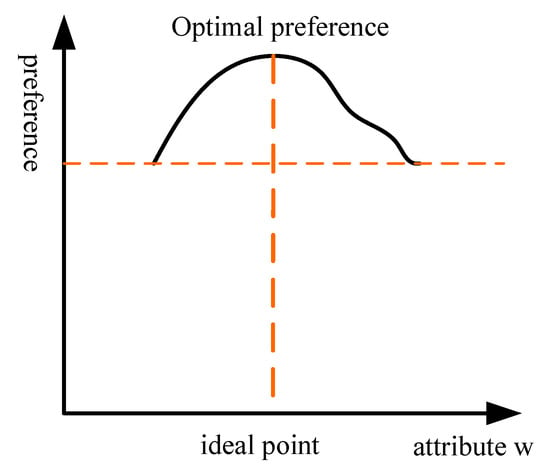

In the ideal point model, an ideal model needs to be determined between parameter selection and weight distance, and its ideal attribute level constitutes the peak point of the curve, as shown in Figure 2, which is an ideal point model figure.

Figure 2.

Ideal point model. The horizontal dotted line shows suboptimal preferences, and vertical dotted line is ideal point.

The utility of the product is negatively related to the square of , and the model is set as:

From the model point of view, the closer the consumption value is to the ideal point, the higher the consumer preference.

(3) Utility function model

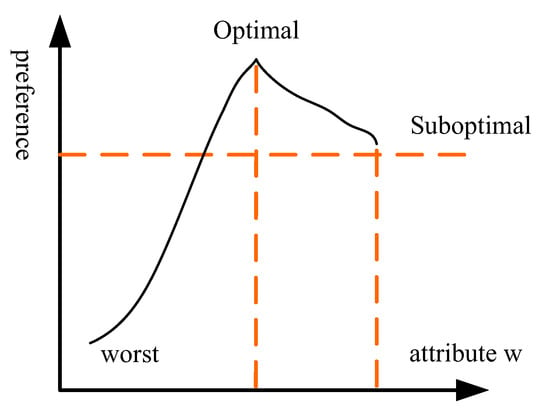

The utility maximization hypothesis and stochastic utility theory serve as the theoretical basis for discrete choice models. The utility function is the key to solving the problem with a discrete choice model, which is used to describe the utility of each attribute at different levels []. Figure 3 shows the utility function model figure.

Figure 3.

Utility function model. The horizontal dotted line shows suboptimal preferences.

For a product, its utility can be expressed as:

The random utility theory states that utility is a random variable.

For decision-makers, the utility of choosing environmentally friendly commodities can be expressed as:

It includes total utility, observable utility, and random utility. The weakness of this theory lies in the existence of overestimating paths with a high probability of selection and underestimating paths with a small probability of selection []. But it can greatly simplify the analysis process and has certain validity and practicality.

In joint analysis, the product is based on the “contour” as the basic element, and each element is based on the “feature element”. When making an actual purchase, consumers are not based on a specific attribute of the product but rather comprehensively consider each attribute and level of the product before making a purchase decision. In this way, a customer’s evaluation of a product can be decomposed into several levels of evaluation, and the weight of these evaluations in determining the purchase value of a product is also known as utility. Joint analysis can be used to describe consumers’ consumption preferences at a specific attribute level. In the consumption model and trend prediction of environmentally friendly goods for residents, the joint analysis method can simulate customers’ purchasing behavior, thereby more objectively and realistically measuring customers’ preference for a certain product and the importance of various characteristics of the product to customers’ purchasing behavior.

2.3. Discrete Choice Models

The discrete choice model is a very effective and practical market research technique. The model allows consumers to choose any product without buying it, which can more realistically simulate the process of consumers purchasing products []. Taking the consumption of environmental protection commodities as the empirical research object, the discrete choice model is used to analyze the consumption preferences of consumers when purchasing environmental protection commodities from the perspective of consumers and determine the main factors that affect consumers’ purchase of environmental protection commodities. Discrete selection models can be divided into three categories based on different types of sample data: discrete-choice models for cross-sectional data, discrete-choice models for non-stationary time-series data, and discrete-choice models for panel data.

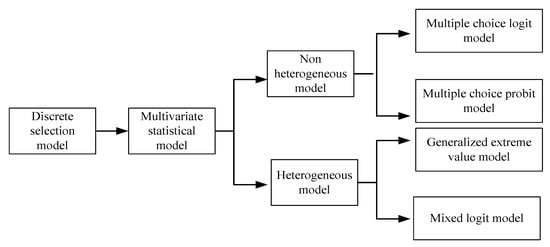

As shown in Figure 4, the discrete choice model differs from other conjoint analysis methods in market research. Instead of asking consumers to rate or rank products, discrete choice models express consumer preferences by learning how consumers choose among a choice set that includes different competing products []. Discrete choice models can analyze substitutability in products.

Figure 4.

Types of discrete choice models.

The main characteristics of discrete choice models are that they can simulate the real market competition environment, making the selection process closer to real purchasing behavior. The attributes and value of products can be inferred based on consumer preferences. The discrete selection model has a certain degree of intelligence, which can analyze unreasonable points in the product combination process and the interaction between products and flexibly handle situations where there are too many product attributes.

The discrete choice model has gradually developed into the most powerful tool to study individual choice behavior used to study consumption preferences. By simulating the process of “consumers make purchase choices when facing different products and their combinations, considering the utility of the attributes of the products”, it provides consumers with products formed by combinations of different attribute levels. It requires consumers to make choices in the product and then use corresponding models to study consumer preferences [].

The discrete choice model is a method of measuring consumers’ choices of various goods. In general, through orthogonal experiments, a discrete selection model can construct a series of product option sets, each containing several product profiles; each composed of attributes that can describe the important characteristics of the product and different combinations of water assigned to each attribute. The discrete choice model can be divided into different forms according to different classification criteria. Discrete choice models can be divided into multiple choice Logit model, generalized extreme value model, multiple choice probit model, and mixed Logit model. Among them, the multi-choice Logit model is the most widely used model for discrete choice models and also the foundation for its development.

(1) Multiple choice Logit model

In 1959, the Logit model was deduced, referred to as the MNL model for short. In the later research, the Logit model was developed from binary selection to multiple selection, and the experimental data was simplified []. The symbolic meaning of the Logit model is based on the extreme value distribution and the value of the goods transported by a standard box. This indicates the total value of goods declared in a batch of goods, the number of standard boxes of the batch of goods (non-standard boxes are converted into equivalent standard boxes), the container model, the value of the 20-foot box is 1, and the value of the 40-foot box is 2. The number of containers of this batch of goods, type 35, is the most mature and widely used discrete choice model. Therefore, it still occupies an important position in practical applications. Assuming that the elements in the multiple-choice Logit model obey the independent same extreme value distribution, then the corresponding density function of the unobservable part of the utility is []:

The joint distribution is obtained as:

The above joint distribution has a non-zero mean and is often used to describe a multiple-choice Logit model.

For the decision maker , the formula for the behavioral probability of choosing option from the choice set is:

Among them, is the systematic utility, which mainly represents the general manifestation of the probability of choice behavior in the multiple-choice Logit model.

A resident environmental protection commodity consumption preference model is established to explore consumers’ preferences for environmental protection commodity consumption. Assume that each consumer chooses from n eco-friendly commodities, where = 1, 2, 3, …, []. According to the utility theory, the utility of consumers’ preferred factors for choosing an environmentally friendly commodity is []:

Taking the preferred factor time utility obtained by the above formula as the probability of maximum time, then according to the MNL model, it can be obtained using:

In the above formula, is assumed; that is, the characteristics of the 0th environmentally friendly commodity are used as the preferred factor. In addition, in the process of establishing the MNL model, it is necessary to select the characteristics of an environmental protection commodity as a reference. Assuming that the characteristics of the 0th environmental protection commodity are used as a reference, then []:

The above formula finally expresses the influence and probability of consumers’ own characteristics on the preferred factors of environmental protection commodities and the relative probability that the characteristics of other environmental protection commodities can be used as preferred factors []. Then in the MNL model, the parameters in the estimated model can be formulated as follows: .

Then the corresponding likelihood function in the above formula is:

Logarithmically expressed as []:

Among the above parameters, the maximum corresponding parameter can be obtained according to the likelihood function. Through pairwise comparison, the influences of residents’ consumers’ preference for environmental protection commodities under different characteristics of environmental protection commodities were analyzed [].

In the MNL model, the probability value that consumers with different characteristics choose a certain characteristic of exchangeable goods can also be obtained as the weight to determine the preference for environmental protection goods []. Determining the consumer-dependent feature vector D in the form of Logit, whose parameters are linear, can be obtained:

The probability of consumers choosing a certain environmentally friendly commodity characteristic can be calculated by the following formula:

In addition, it is also possible to consider the probability of consumers’ preference for environmentally friendly products with a combination of single statistical factors and multi-factor characteristics and make a directional prediction of the consumers’ preference for environmentally friendly products.

(2) Generalized extreme value model

This model allows correlation between model options. Assuming that the unobservable part of the utility of all options in the model, that is, the random utility, obeys the generalized extreme value joint distribution, then it can be got:

Then the decision maker’s behavioral choice probability for commodity options is:

When the correlation between the definition options is zero, the generalized extreme value distribution is an independent extreme value distribution, and the generalized extreme value model becomes a multiple-choice Logit model. In many cases, the multiple-choice Logit model is considered to be a more specific form of dispersion derived from the generalized extreme value model []. It takes into account the correlation between the random utilities of different options while ensuring the accuracy of the probabilistic analytical form of behavioral choice.

(3) Multiple choice Probit model

This model is derived assuming that the unobservable part of utility follows a joint normal distribution. The model is not restricted by the condition of independent and identical distribution, so the degree of freedom of the model is very high, and problems such as correlation, surrogate mode, and random preference difference can be solved by setting the covariance structure []. However, the disadvantage of the model is that the setting is more complicated, the calculation results are poor when faced with a large amount of data, and it will expand rapidly with the increase in the number of calculations in the process. The formula for the probability of selection is:

(4) Hybrid Logit model

The mixed Logit model can solve the problem of random preference and multiple correlations by introducing randomness coefficients to represent the correlation between random utilities. Given an individual in the model, the independent variable is a constant value with different dependent variable options, and each choice is independent, which provides convenience for consumers to choose []. The mixed Logit selection model includes independent variables that change with the change of options, as well as independent variables with constant options, which can well reflect the random preference differences in consumer groups. In the model, the dependent variable is which product consumers choose to purchase among multiple optional environmentally friendly products; The independent variable is the different environmental product attributes that make up the selection set.

Its general form is:

When the mixed Logit model is used to deal with the correlation problem, it is also called the error component model []. The mixed Logit model expresses the selection probability of a Logit mixture with a specific mixture distribution, and the behavioral selection probability can be expressed as:

3. Experiment and Structure of the Consumption Model and Trend Prediction of Residents’ Environmental Protection Products Based on Consumer Preference

3.1. Deconstruction of Residents’ Consumption Preference for Environmentally Friendly Products

In order to verify the effectiveness of residents’ consumption model and trend prediction of environmental protection goods based on consumer preferences, this article takes the utility function model in the conjoint analysis method and the multiple choice Logit model in the discrete choice model as examples to analyze the changes of residents’ consumption of environmental protection goods before and after the application of the consumption analysis model. For the consumption preference of environmentally friendly commodities, this paper uses the range of choices that consumers consider when making purchase decisions to assign clear values and uses the conjoint analysis method and discrete choice model to analyze the consumers’ choice to buy environmentally friendly commodities. This article takes consumer users of a certain brand’s online shopping transaction physical store as the research object and uses their consumption records as the dataset to conduct experimental analysis on their consumption preferences for environmentally friendly products. In this analysis, 329 consumers were randomly selected from the consumer user group of the physical store, and these 329 consumers had more than 2 consumption experiences in the physical store. This article divided their age groups into: under 18 years old, 18–25 years old, 26–40 years old, 41–60 years old, and over 60 years old. The article first analyzes the age group of residents who purchase environmentally friendly products, as shown in Table 1. The variance analysis of consumption preferences for environmentally friendly goods among different age groups is shown in Table 2. Residents add 1 for each type of consumption, with a minimum of 0 and a maximum of 4.

Table 1.

Age of Residents’ Consumption of Environmentally Friendly Commodities.

Table 2.

Variance analysis of consumption preferences for environmentally friendly goods among different age groups.

As shown in Table 1, the consumption of environmental goods by residents under the age of 18 accounts for 0.61% of the total consumption of environmental goods by residents; the consumption of environmental goods by residents aged 18–25 accounts for 31% of the total consumption of environmental goods by residents; the consumption of environmental goods by residents aged 26 to 40 accounts for 41.34% of the total consumption of environmental goods by residents; the consumption of environmentally friendly goods by residents aged 41 to 60 and over accounts for 24.62% and 2.43% of the total consumption of environmentally friendly goods by residents. Therefore, the age group of the consumers of environmentally friendly commodities is mainly between adults and 60 years old, especially the people between 26 and 60, whose consumption is stable and representative. Consumers in this age group have a higher desire to purchase environmentally friendly products due to their higher economic ability and rising consumption outlook, and environmental awareness.

From Table 2, it can be seen that residents of different age groups have significant differences in their consumption preferences for environmentally friendly goods.

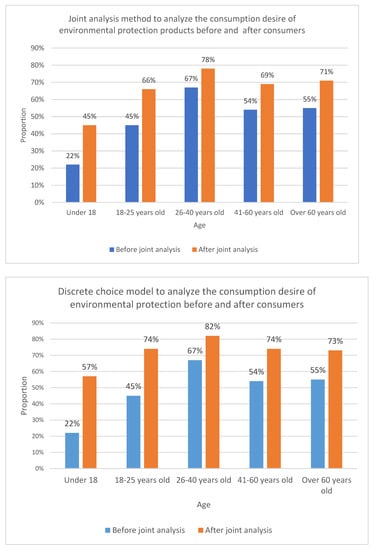

Due to significant differences in consumer preferences for environmentally friendly products among different age groups, this article is based on two consumption models to assist consumers in making consumption decisions and compares the changes in consumers’ desire for environmentally friendly products before and after the application of the consumption model, as shown in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

The transformation of residents’ consumption desire before and after the application of joint analysis and discrete choice model.

As shown in Figure 5, under the two consumption models, consumers aged 26–40 have a higher desire to consume environmentally friendly products. However, stimulated by the consumption model, consumers’ consumption desire has increased among all age groups. Among them, in the conjoint analysis method, the consumption desire of residents under the age of 18 for environmentally friendly products increased by 23%, but in the discrete choice model, the consumption desire increased by 35%. Compared with the conjoint analysis method, the discrete choice model is 12% more effective in stimulating consumption desire, the stimulation effect is better, and the span of stimulating consumption in this age group is the largest. In the 26–40-year-old age group, the increase in consumers’ desire to consume environmentally friendly products is not as high as that of other age groups, but it also has a certain stimulating effect. It can be seen from the figure that under the same conditions, the consumption model that can mobilize the enthusiasm of consumers is the discrete choice model, which is higher than the conjoint analysis method to a certain extent. The discrete selection model mainly measures consumers’ purchasing behavior by simulating the competitive environment of the product market in order to understand how consumers make choices under different product attribute levels and price conditions. It is conducive to highlighting the value of environmentally friendly goods themselves and their contribution to the overall utility compared to other ordinary goods, so it is more conducive to arousing consumers’ purchasing enthusiasm.

3.2. Accuracy and Consumption Trend of Environmental Protection Product Selection through Consumption Model

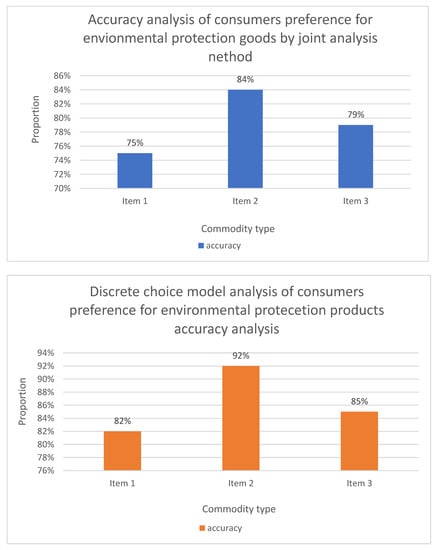

This article takes energy-saving appliances as an example, selects three types of energy-saving air conditioning and environmental protection products, uses the joint analysis method and discrete selection model to analyze the accuracy of consumers’ consumption preferences for the three types of environmental protection products, and observes the accuracy of the two model algorithms on consumer consumption preferences. Figure 6 shows the comparison of the accuracy of consumer preference calculation between the two model algorithms under the same conditions.

Figure 6.

Accuracy of conjoint and discrete choice models in analyzing consumer preferences.

By analyzing the accuracy of residents’ consumption preferences for the three environmental protection commodities under the conjoint analysis method and the discrete choice model, it is found that in the discrete choice model, the residents have higher accuracy for the environmental protection commodities. It can be seen from the figure that for commodity 1, commodity 2, and commodity 3, the accuracy of the discrete selection model is 82%, 92%, and 85%, and the prediction accuracy is higher than that of the joint analysis method by 7%, 8%, and 6% respectively. It can be seen that the prediction accuracy of the discrete choice model is higher than that of the conjoint analysis method, and the discrete choice model is more suitable for analyzing consumer preferences.

3.3. Predicting the Consumption Trend of Residents’ Environmental Protection Products Based on Consumer Preferences

The numerical characteristics of the model parameter estimates of residents’ consumption of environmentally friendly commodities in the discrete choice model under different conditions are shown in Table 3.

Table 3.

Numerical features of discrete choice model parameters.

As shown in Table 3, p represents the p-value of the normality test for verifying residents’ consumption of environmentally friendly commodities in the discrete choice model. For the p value, less than 0.05, the model shows that the distribution of consumers’ feature selection in environmental protection consumption is significantly different from the normal distribution of p. It can be seen from the table that residents’ purchases of environmentally friendly commodities conform to a normal distribution, and then the maximum value calculation can be performed on the data, and the maximum likelihood function can be used to estimate. The parameters were repeated 1000 times under different conditions. When γ = 0.5, under each sample size, the mean value is greater than 0.5, so it conforms to the normal distribution. Therefore, the discrete choice model is very suitable for estimating the purchase of green goods.

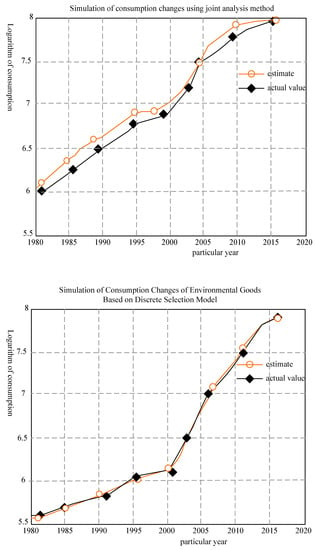

There are many characteristic factors that affect consumers’ preferred choice of environmentally friendly products. To analyze the characteristics of consumers when purchasing environmentally friendly goods, this article uses joint analysis and discrete selection model analysis to simulate the consumption of environmentally friendly goods by residents from 1980 to 2020. The changes are shown in Figure 7.

Figure 7.

Comparison of the consumption changes of environmental goods simulated by joint analysis method and discrete selection model.

As shown in Figure 7, the joint analysis method differs significantly from the simulated and actual values of the discrete choice model in analyzing the changes in consumer consumption of environmentally friendly goods. During the simulation process using the joint analysis method, it was found that only in 2005, when the logarithm of consumption was 7.5, and in 2015, when the logarithm of consumption was close to 8, the simulated values and actual values were similar. Under other conditions, the error between the simulated values and the actual values was relatively large; Under the same conditions, the simulated values of the discrete choice model for commodity consumption are basically similar to the actual values, with small error values. Therefore, under the same conditions, choosing a discrete selection model to simulate the consumption of environmentally friendly goods is more accurate, with significant changes in consumer purchases and smaller errors.

4. Discussion

This article is based on consumer preference for the consumption model and trend forecast of residents’ environmental protection commodities. The article first analyzes and discusses consumer preferences and proposes two methods for constructing consumption models for commodities. One is the conjoint analysis method, and the other is the discrete choice model, which analyzes the consumption of environmental protection commodities by residents respectively. Among them, the preferred vector model, ideal point model, and utility function model are proposed in the conjoint analysis method. According to different types of sample data, discrete choice models are divided into multiple choice Logit models, generalized extreme value models, multiple choice Probit models, and mixed Logit models. Then, the attitudes of consumers when choosing commodities are analyzed respectively, and the purchasing motives that consumers consider when choosing commodities and the influencing factors when they purchase commodities are judged, and two analysis models are used to conduct experimental analysis on residents’ purchase of environmentally friendly commodities. The experimental results show that the discrete choice model is superior to the conjoint analysis method both in stimulating consumers’ desire to purchase and in predicting the accuracy of residents’ purchase of environmentally friendly products.

5. Conclusions

This article has explored and calculated consumer preferences and desired models for a certain product, and it also analyzed consumer behavior and predicted trends based on consumer preferences. This article selected two models to analyze consumer behavior. Joint analysis is a method of determining consumer psychology and analyzing consumer behavior. This method can establish preference models based on consumer preferences. The discrete choice model is a model in which consumers’ preferences are determined by their choices of goods in different competitive products. These two analysis models each have their own advantages and disadvantages. In the experimental part, it was found that a more discrete selection model can stimulate consumers’ enthusiasm, which is, to some extent, greater than the joint analysis method. This article uses joint analysis methods and discrete selection models to analyze the accuracy of consumers’ consumption preferences for three environmental protection products. It is found that the discrete selection model has a higher accuracy of consumer consumption preferences than the joint analysis method. When analyzing the numerical characteristics of the parameters of the discrete choice model, it is found that the parameters of the discrete choice model basically conform to the normal distribution, so the discrete choice model has a great impact on the estimation of environmental protection commodity procurement. In the practical application of the two methods, many factors need to be considered, and detailed analysis is also needed. In future research, it will consider improving consumer analysis models to identify and analyze the influencing factors of residents’ consumption trends of environmentally friendly goods from more perspectives.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, X.Z.; writing—original draft preparation, L.X.; writing—review and editing, G.J. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The experimental data can be obtained by contacting the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Cui, Z.Z.; Li, J.F.; Wang, H.J. The Impact of Urban Environmental Quality Perception on the Willingness of Community Residents’ Ecological Consumption: Based on the Mediating Effect Model of Environmental Protection Knowledge Accumulation. Consum. Econ. 2021, 37, 68–77. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, G.Q.; Liu, R.J.; Wang, J.G. Research on the Internal Mechanism of “Ant Forest” Users Migrating to Offline Green Consumption: Based on Behavioral Reasoning Theory. J. Manag. 2023, 36, 56–69. [Google Scholar]

- Hasan, F.; Bellenstedt, M.F.R.; Islam, M.R. The impact of demand and supply disruptions during the COVID-19 crisis on firm productivity. Glob. J. Flex. Syst. Manag. 2023, 24, 87–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meiryani, M.; Tandyopranoto, C.D.; Emanuel, J.; Lindawati, A.; Fahlevi, M.; Aljuaid, M.; Hasan, F. The effect of global price movements on the energy sector commodity on Bitcoin price movement during the COVID-19 pandemic. Heliyon 2022, 8, e10820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, R. A Study of Consumer’s Behavior Towards Green Electronic Products: An Application of Theory of Planned Behavior. Indian J. Environ. Prot. 2018, 38, 302–313. [Google Scholar]

- Wysokinska, Z. A Review of Transnational Regulations in Environmental Protection and the Circular Economy. Comp. Econ. Res. Cent. East. Eur. 2020, 23, 149–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, F.; Xu, J.; Xue, L. Voluntary environmental program: Research progress and future prospect. China Popul. Resour. Environ. 2020, 1, 74–82. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, M.T.; Ho, S.H. The Influence of Environmental Awareness on Intent to Use Electric Scooters: Perspectives Based on the Theory of Planned Behavior. J. Bus. Manag. Sci. 2021, 9, 156–164. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, W.; Hasegawa, T.; Ohashi, H.; Hanasaki, N.; Liu, J.; Matsui, T.; Fujimori, S.; Masui, T.; Takahashi, K. Global advanced bioenergy potential under environmental protection policies and societal transformation measures. GCB Bioenergy 2019, 11, 1041–1055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Millan, E.; Mittal, B. Consumer Preference for Status Symbolism of Clothing: The Case of the Czech Republic. Psychol. Mark. 2017, 34, 309–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Keh, H.T.; Lee, A.Y. Shaping consumer preference using alignable attributes: The roles of regulatory orientation and construal level. Int. J. Res. Mark. 2019, 36, 151–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rozi, F.; Santoso, A.B.; Mahendri, I.G.; Hutapea, R.T.; Wamaer, D.; Siagian, V.; Elisabeth, D.A.; Sugiono, S.; Handoko, H.; Subagio, H.; et al. Indonesian market demand patterns for food commodity sources of carbohydrates in facing the global food crisis. Heliyon 2023, 9, e16809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khan, S.; Yao, L.; Khan, Z.A.; Ali, U.; Zhao, M. Exploring stakeholder preferences and spatial heterogeneity in policy scenario analysis for vulnerable ecosystems: A choice experiment approach. Ecol. Indic. 2023, 153, 110438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katare, B.; Yim, H.; Byrne, A.; Wang, H.H.; Wetzstein, M. Consumer willingness to pay for environmentally sustainable meat and a plant-based meat substitute. Appl. Econ. Perspect. Policy 2023, 45, 145–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.G.; Yu, Z.Q.; Zhang, S.S.; Peng, J.L. Three stage game research of dual-channel supply chain of fresh agricultural products under consumer preference. Int. J. Comput. Sci. Math. 2018, 9, 48–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.J.; Lee, C.K.; Jung, T. Exploring consumer behavior in virtual reality tourism using an extended stimulus-organism-response model. J. Travel Res. 2020, 59, 69–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, H. Consumer behavior and environmental sustainability in tourism and hospitality: A review of theories, concepts, and latest research. J. Sustain. Tour. 2021, 29, 1021–1042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Payini, V.; Mallya, J.; Piramanayagam, S. Indian women consumers’ wine choice: A study based on conjoint analysis. Int. J. Wine Bus. Res. 2022, 34, 469–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Wang, H.F.; Cho, J.H. Consumer Preference for Yogurt Packaging Design Using Conjoint Analysis. Sustainability 2022, 14, 3463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sindhuja, S.; Arathi, P. An economic order quantity model for Pareto distribution deterioration with linear demand under linearly time-dependent shortages. Eur. J. Ind. Eng. 2022, 16, 418–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.W.; Feng, Q.; Li, J.; Tong, S.R. Modeling and Solving Multilinear Utility Function Based on 2-additive Fuzzy Measures. Oper. Res. Manag. Sci. 2021, 30, 113–119. [Google Scholar]

- Ibrahim, N. Empirical Analysis of the Global Supply and Demand of Entrepreneurial Finance: A Random Utility Theory Perspective. J. Open Innov. Technol. Mark. Complex. 2022, 8, 26. [Google Scholar]

- Motz, A. Consumer acceptance of the energy transition in Switzerland: The role of attitudes explained through a hybrid discrete choice model. Energy Policy 2021, 151, 112152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czine, P.; Torok, A.; Peto, K.; Horvath, P.; Balogh, P. The Impact of the Food Labeling and Other Factors on Consumer Preferences Using Discrete Choice Modeling-The Example of Traditional Pork Sausage. Nutrients 2020, 12, 1768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, M.; Kim, S.; Kim, J. Can mobile and biometric payments replace cards in the Korean offline payments market? Consumer preference analysis for payment systems using a discrete choice model. Telemat. Inform. 2019, 38, 46–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.M. Research on the Correlation Between Profit Information and Corresponding Cumulative Abnormal Return from Listed Companies in China: Based on Logit Model. Shanghai Manag. Sci. 2023, 45, 68–72. [Google Scholar]

- Norton, E.C.; Dowd, B.E. Log odds and the interpretation of logit models. Health Serv. Res. 2018, 53, 859–878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, H.T.; Sui, D.C.; Wu, H.X.; Zhao, M.J. Public Preference and Willingness to Pay for the Heihe River Watershed Ecosystem Service: An Empirical Study on Choice Experiments. Sci. Geogr. Sin. 2019, 39, 342–350. [Google Scholar]

- Lipovetsky, S. Logistic and multinomial-logit models: A brief review on their modifications and extensions. Model Assist. Stat. Appl. 2021, 16, 279–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norton, E.C.; Dowd, B.E.; Maciejewski, M.L. Marginal effects—Quantifying the effect of changes in risk factors in logistic regression models. JAMA 2019, 321, 1304–1305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Witek, L. Attitude-Behaviour Gap Among Polish Consumers Regarding Green Purchases. Visegr. J. Bioecon. Sustain. Dev. 2019, 8, 31–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, K.; Shibata, K. Relationships between Consumers’ Pro-Environmental Behaviors and Daily Life Values. J. Life Cycle Assess. Jpn. 2019, 15, 199–210. [Google Scholar]

- Bellundagi, V.; Umesh, K.B.; Hamsa, K.R. Ex-ante Producer and Consumer Preference for Finger Millet in Karnataka: Application of Conjoint analysis and Logit Model. Curr. J. Appl. Sci. Technol. 2018, 30, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, J.L.; Zhou, J.W. Research on Jiaozhou residents’ travel behavior choice based on multinomial Logit model. Mod. Electron. Tech. 2021, 44, 169–172. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, Y.C.; Wei, H.; Zeng, Q. Analysis of Freeway Crash Severity Based on Spatial Generalized Ordered Probit Model. J. S. China Univ. Technol. Nat. Sci. Ed. 2023, 51, 114–122. [Google Scholar]

- Cao, X.J.; Dai, L.H.; Wang, Y.; Li, S.Q.; Li, Y.J. Analysis on the influencing factors of Chinese rural residents choice of medical treatment based on mixed Logit model. Soft Sci. Health 2022, 36, 82–86. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, R.J.; Gu, G.F. Factors Impacting Purchasing Intentions to Electric Vehicles Based on Mixed Logit Model. Transp. Res. 2021, 7, 95–103+114. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).