How to Distribute Green Products in Competition with Brown Products? Direct Selling versus Agent Selling?

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Production and Sales of Green Products in Supply Chain

2.2. Channel Selection in Supply Chain

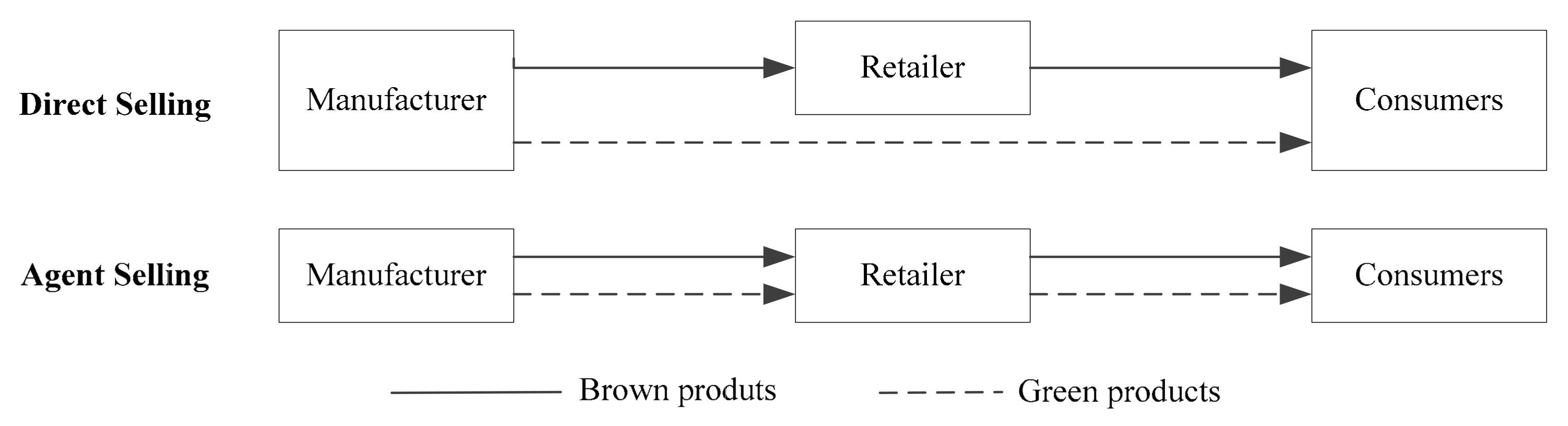

3. Problem Description

4. Green Product Selling Channels

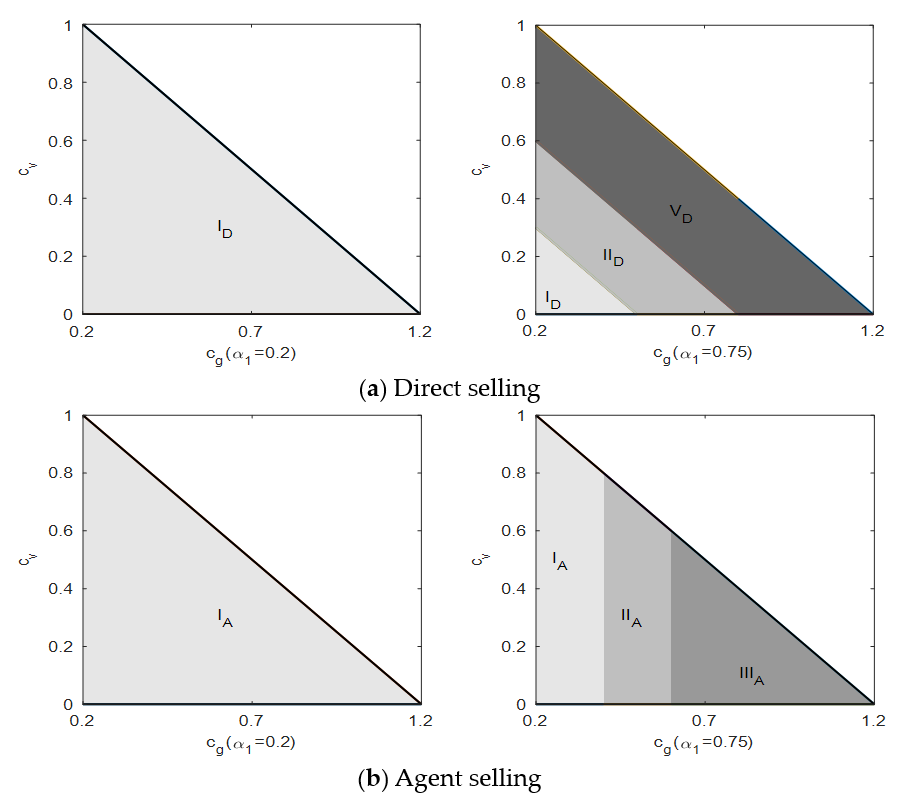

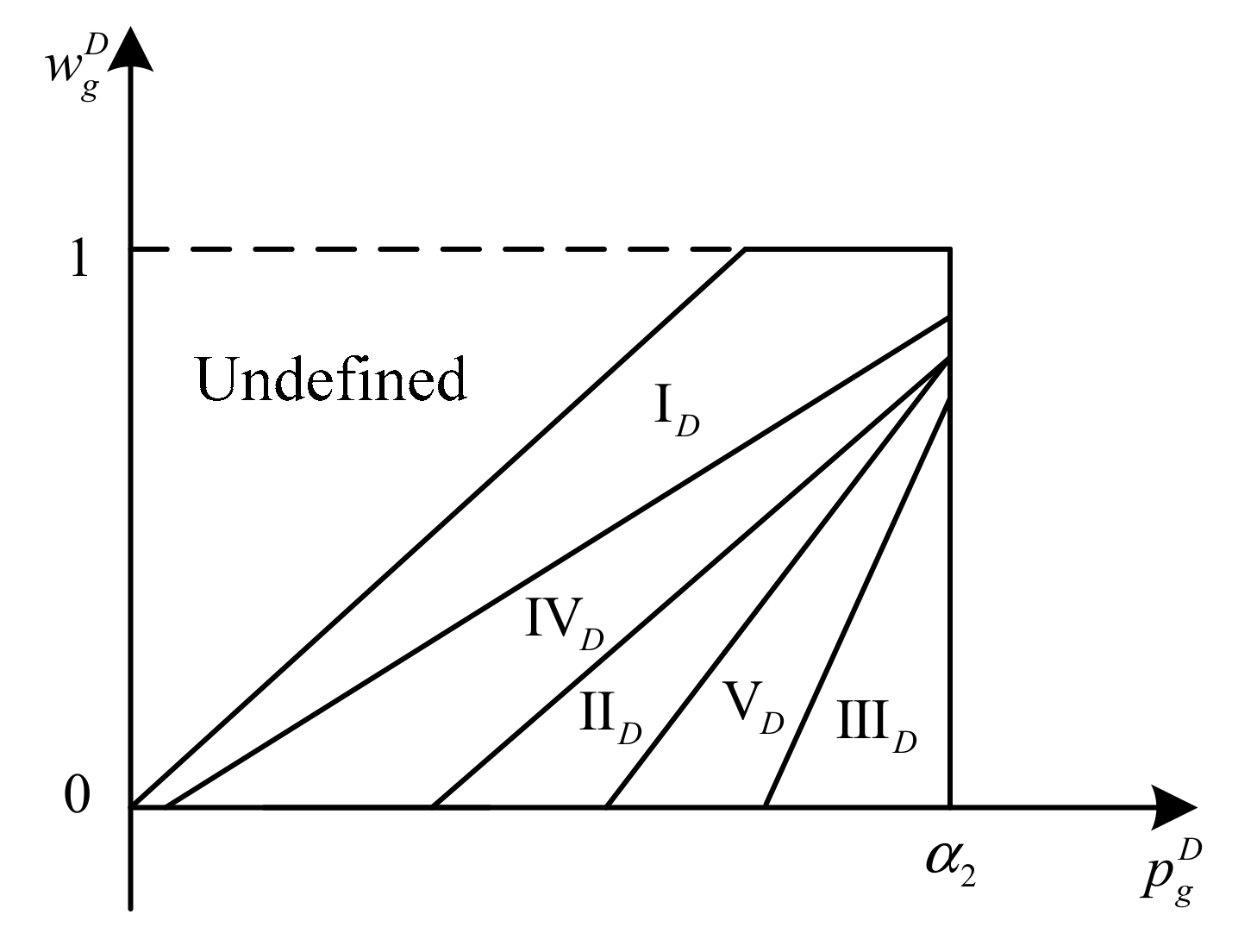

4.1. Direct Selling

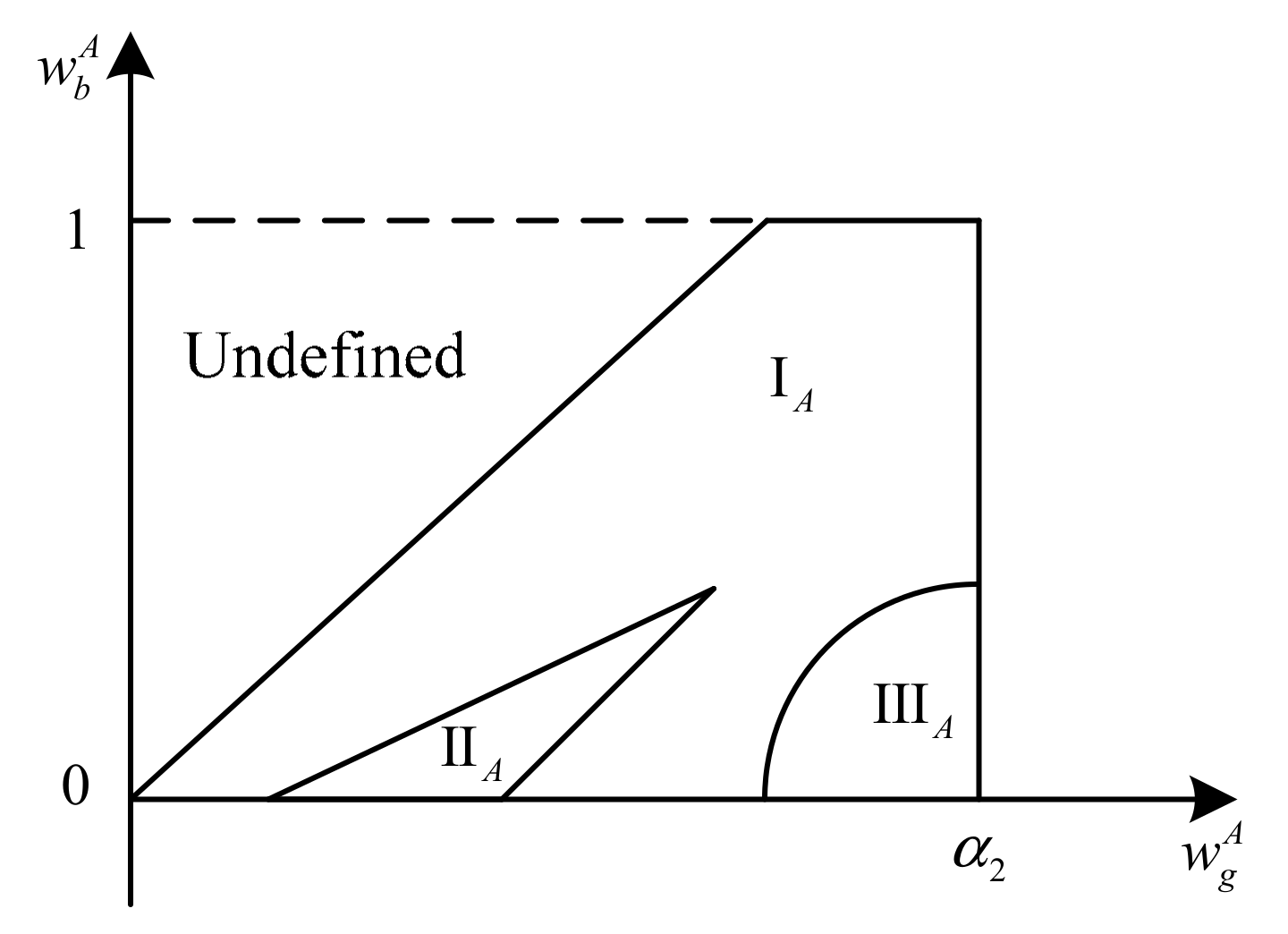

4.2. Agent Selling

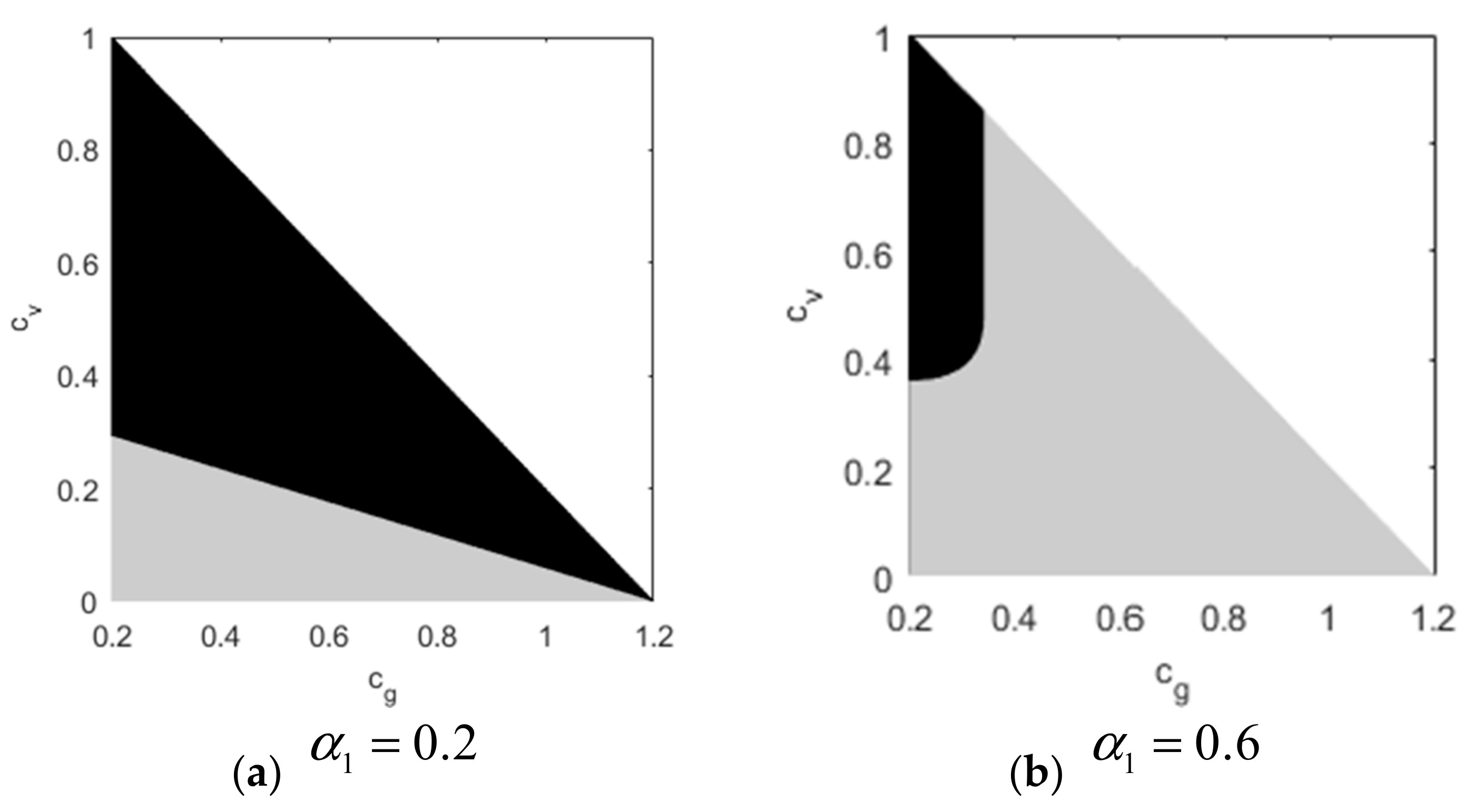

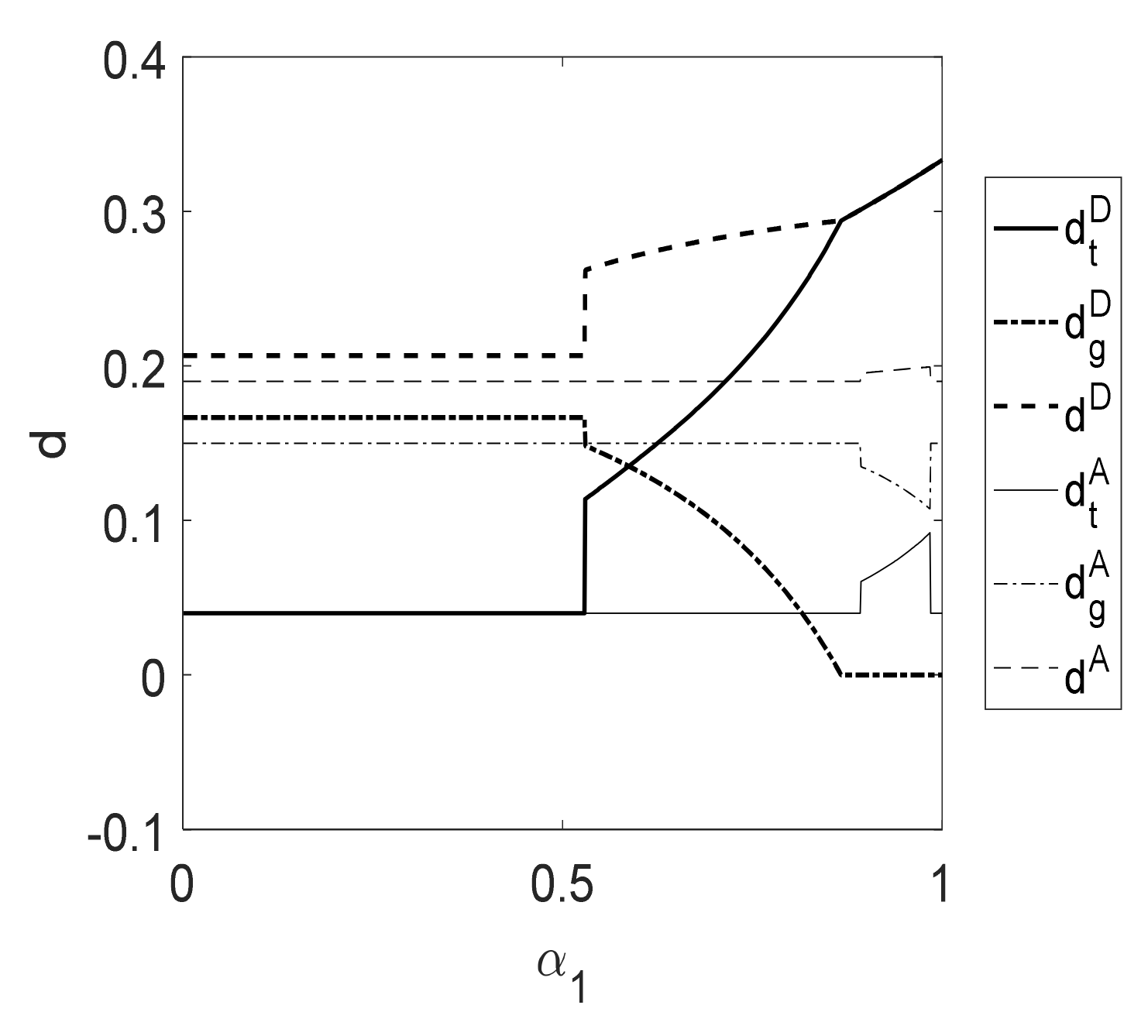

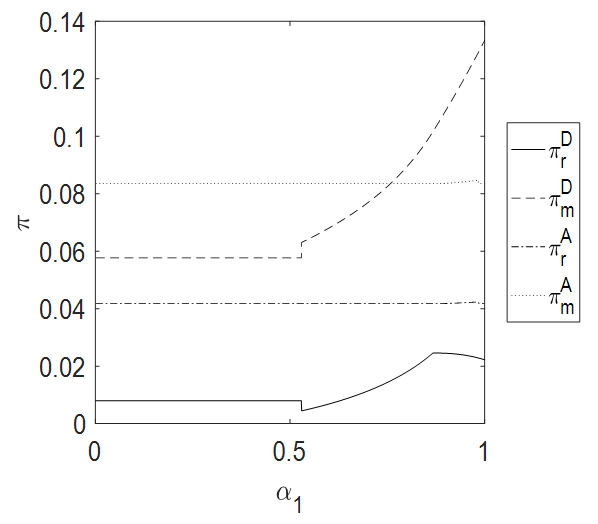

5. Comparative Statics

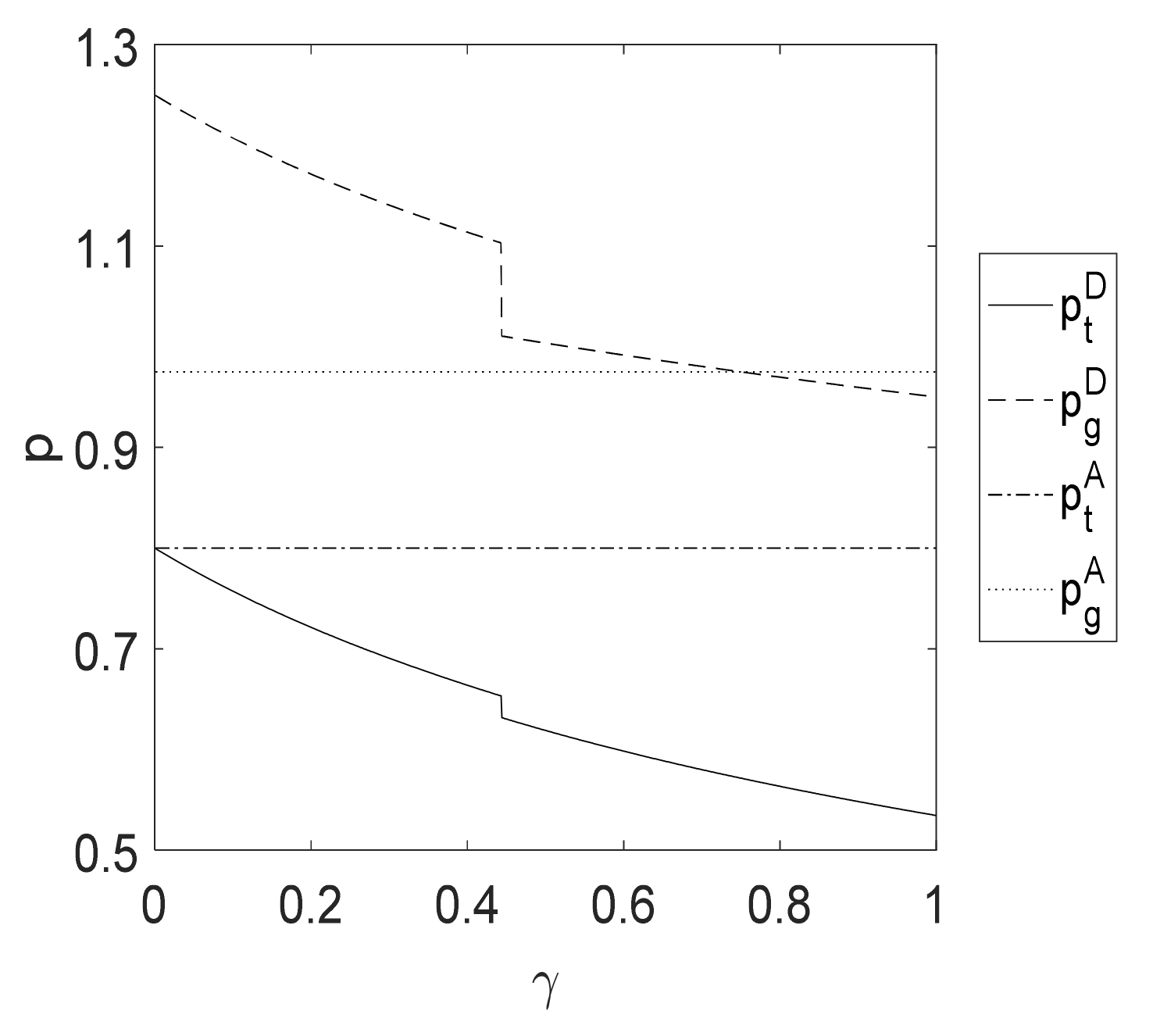

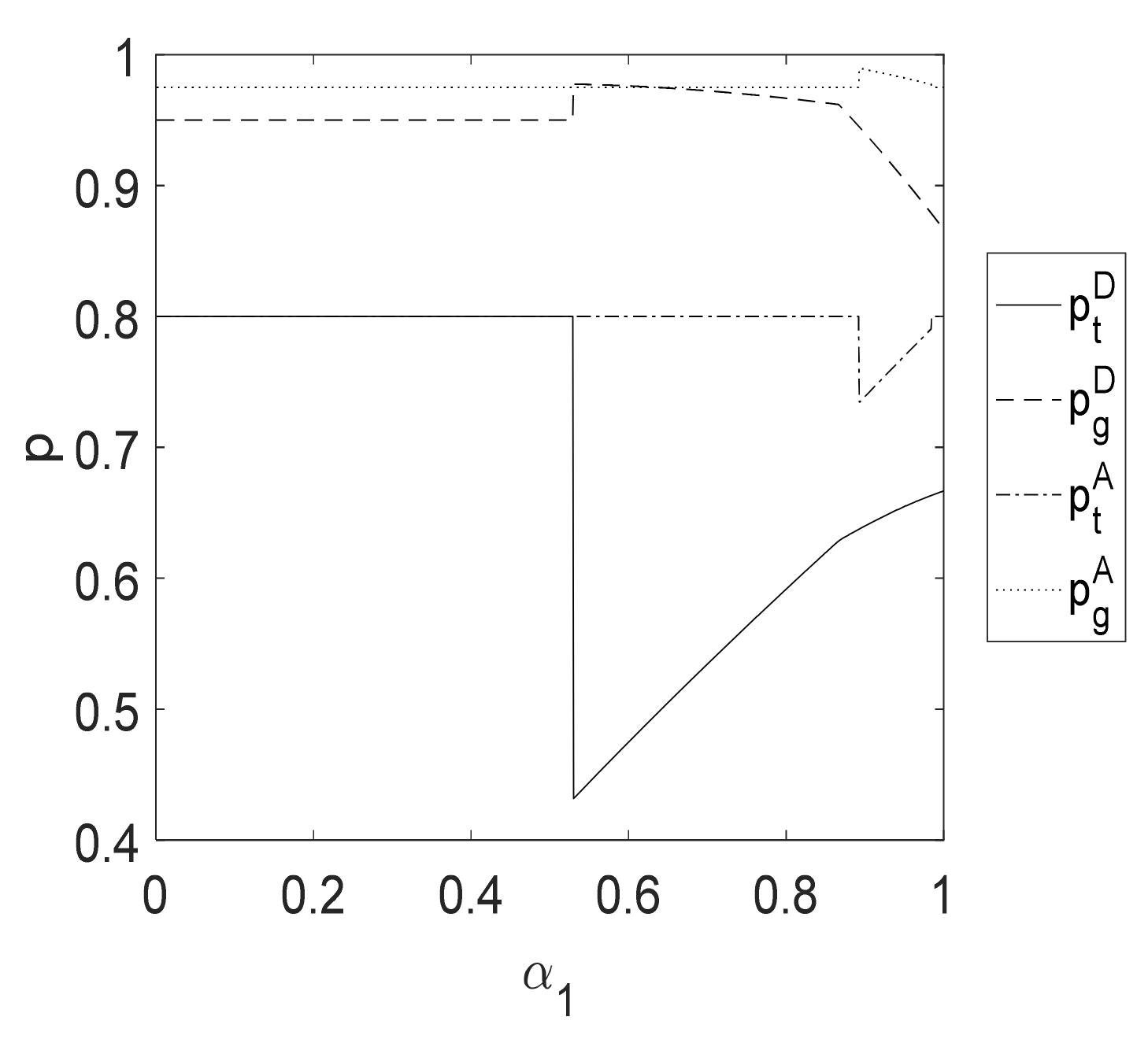

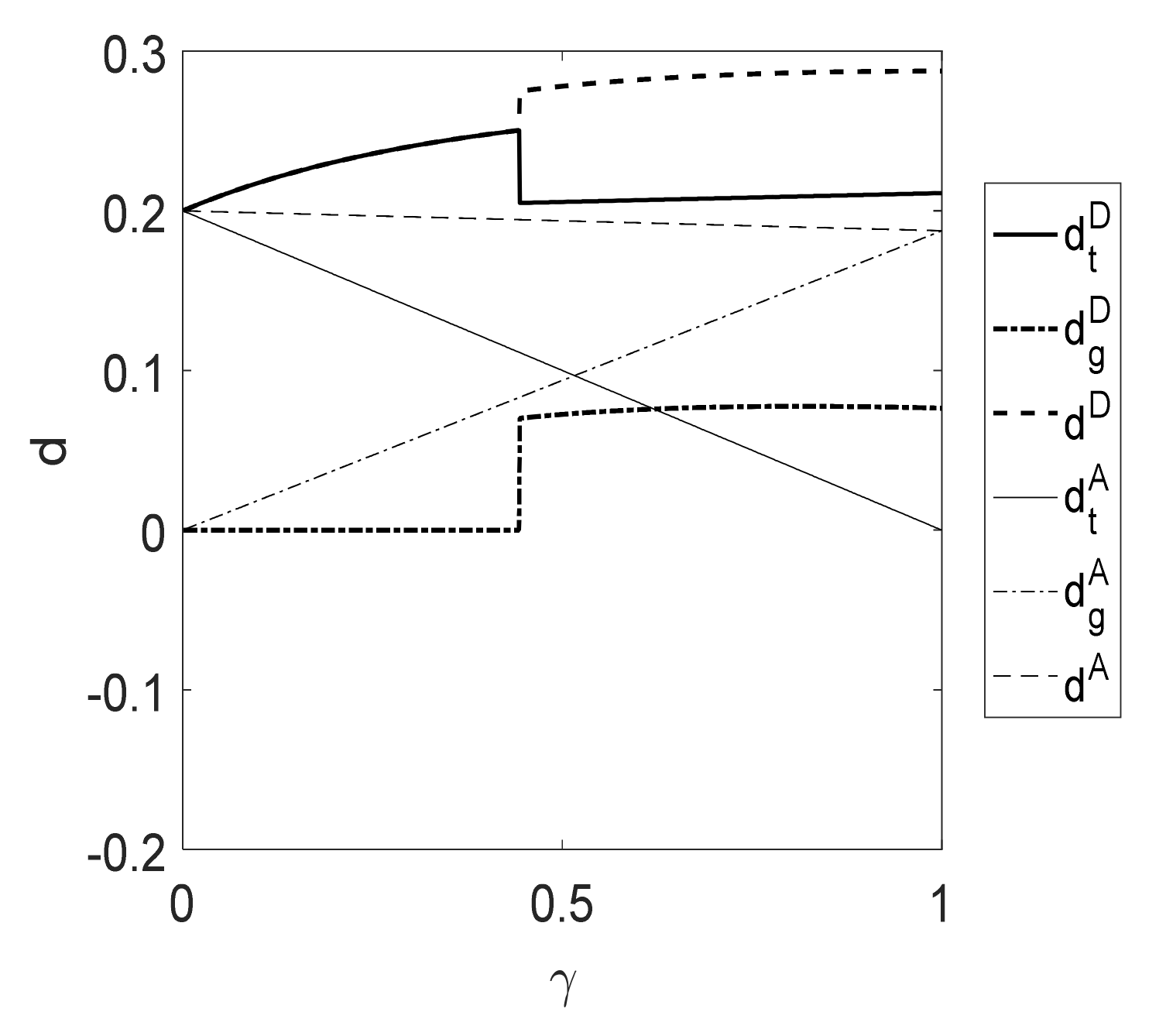

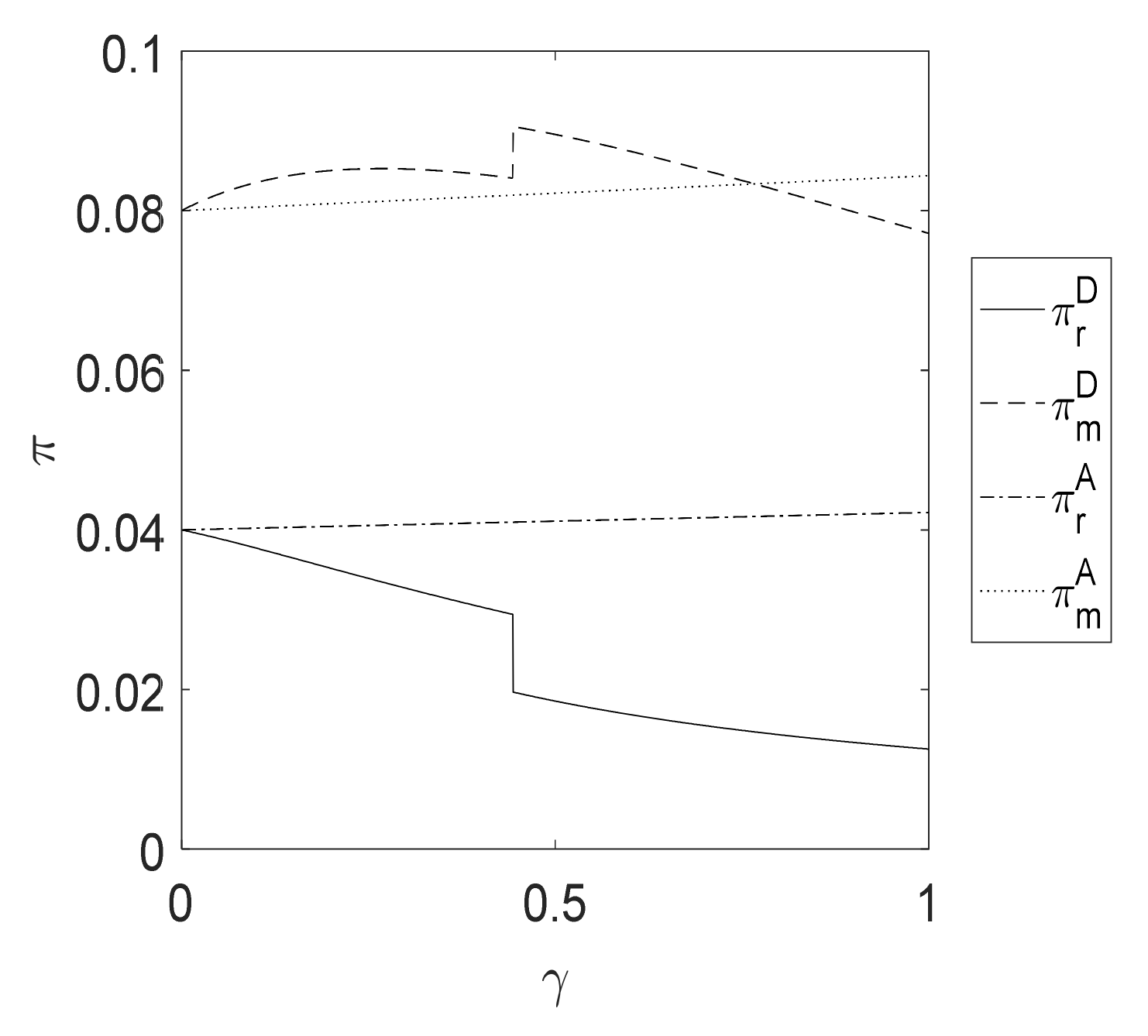

5.1. Pricing Strategies

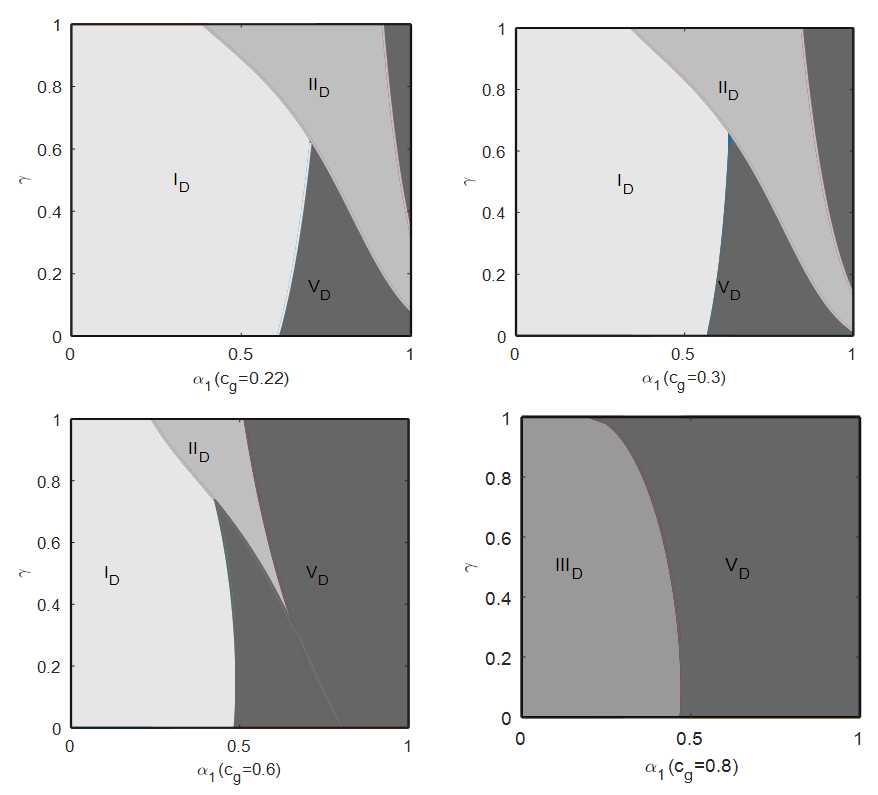

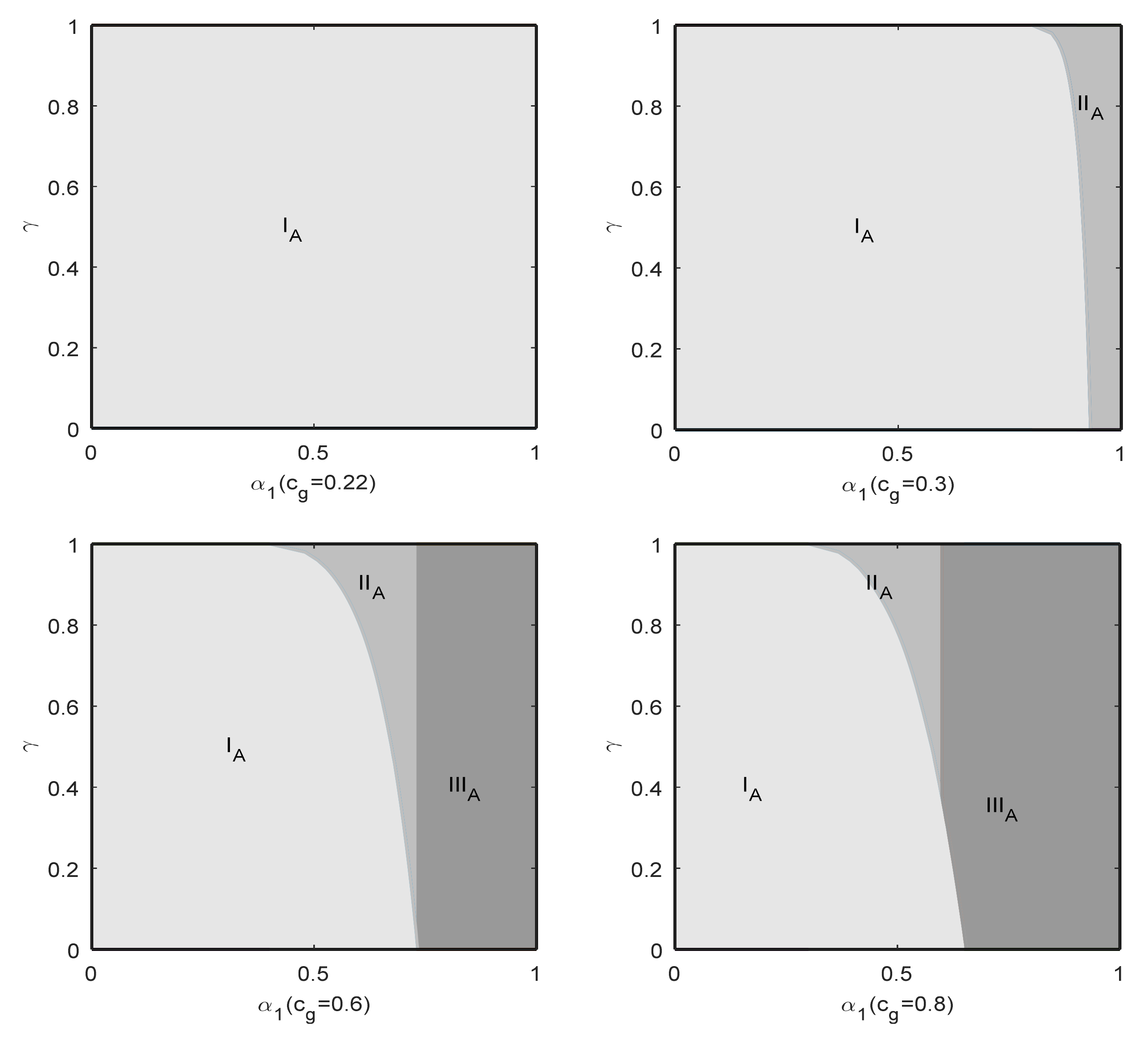

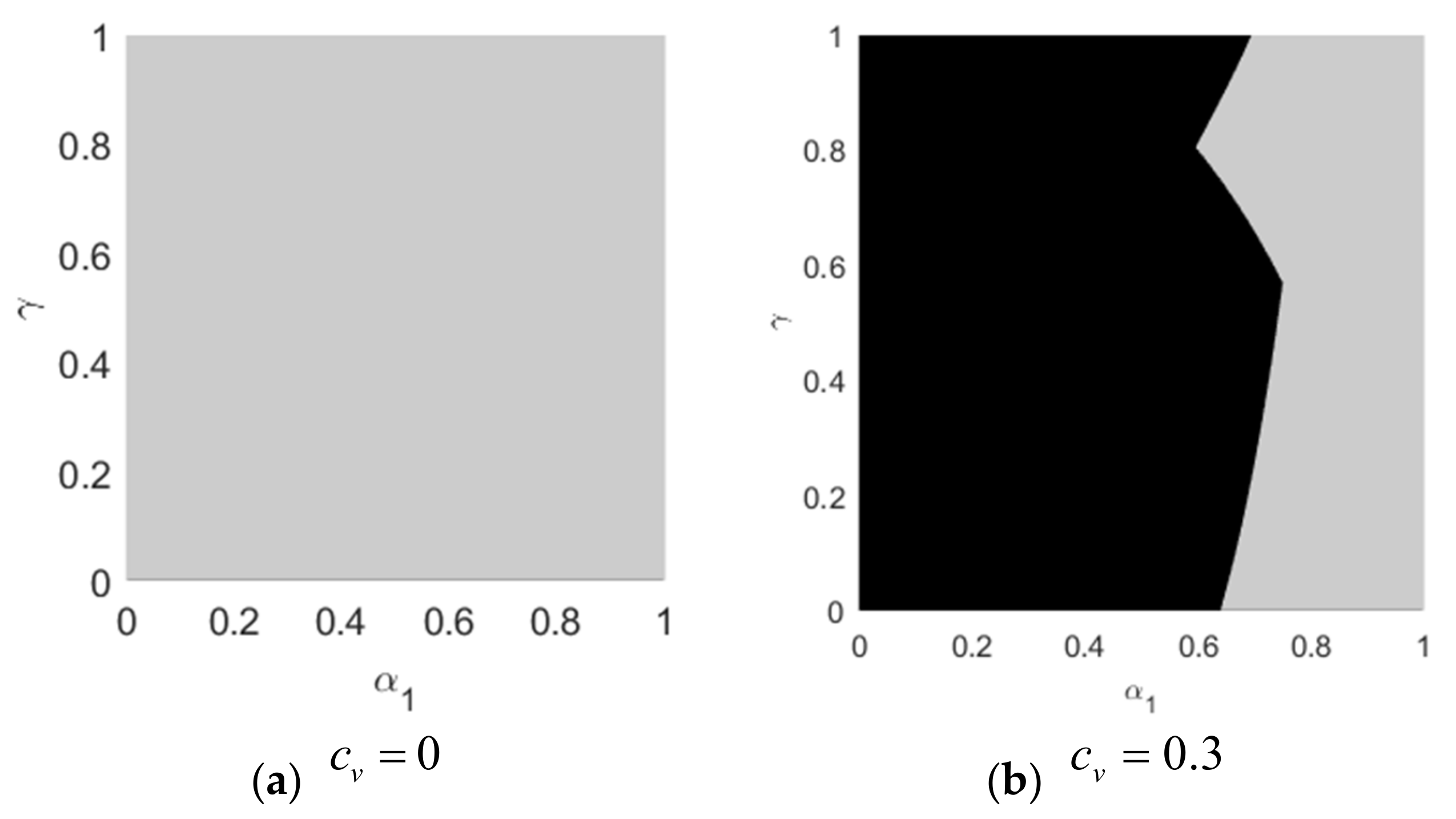

5.2. Sales Channel Choice

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

Appendix B

References

- Shi, D.; Zhang, W.J.; Zou, G.Y.; Ping, J.K. Advertising and pricing strategies for the manufacturer in the presence of brown and green products. Kybernetes 2022, 51, 1452–1476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, Z.; Guo, X. Green product supply chain contracts considering environmental responsibilities. Omega 2019, 83, 155–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; Li, L.; Choi, T.M.; Sethi, S.P. Green supply chain management in Chinese firms: Innovative measures and the moderating role of quick response technology. J. Oper. Manag. 2020, 66, 958–988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghazali, I.; Abdul-Rashid, S.H.; Dawal, S.Z.M.; Irianto, I.; Herawan, S.G.; Ho, F.H.; Abdullah, R.; Rasib, A.H.A.; Padzil, N.W.S. Embedding green product attributes preferences and cultural consideration for product design development: A conceptual framework. Sustainablilty 2023, 15, 4542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dey, K.; Roy, S.; Saha, S. The impact of strategic inventory and procurement strategies on green product design in a two-period supply chain. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2018, 57, 1915–1948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inman, R.A.; Green, K.W. Lean and green combine to impact environmental and operational performance. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2018, 56, 4802–4818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Zhou, H. The optimal green product design with cost constraint and sustainable policies for the manufacturer. Math. Probl. Eng. 2019, 2019, 7841097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, G.; Biswas, I.; Srivastava, K.S. Managing supply chain with green and non-green products: Channel coordination and information asymmetry. Manag. Decis. Econ. 2022, 44, 1359–1372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, T.; Choi, T.M.; Cheng, T.C.E. Product variety and channel structure strategy for a retailer-Stackelberg supply chain. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2014, 233, 114–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, E.; Ma, Y.; Wan, C.; Lai, M. Contracting with asymmetric cost information in a dual-channel supply chain. Oper. Res. Lett. 2013, 41, 410–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hafezalkotob, A. Competition of two green and regular supply chains under environmental protection and revenue seeking policies of government. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2015, 82, 103–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Zhu, M.; Jiang, Y.; Li, Z. Pricing policies of a competitive dual-channel green supply chain. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 112, 2029–2042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, W.; Zou, J.; Liu, T.L. Integrated or decentralized: An analysis of channel structure for green products. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2017, 112, 20–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, Z.; Wang, Y.; Liu, Y.; Chen, Y.J. The impact of consumer fairness seeking on distribution channel selection: Direct selling vs. agent selling. Prod. Oper. Manag. 2018, 27, 1148–1167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranjan, A.; Jha, J.K. Pricing and coordination strategies of a dual-channel supply chain considering green quality and sales effort. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 218, 409–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Song, Q. Pricing policies for dual-channel supply chain with green investment and sales effort under uncertain demand. Math. Comput. Simulat. 2019, 171, 79–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.; Ma, W.; Si, H.; Liu, J.; Liao, L. Cooperative game analysis of coordination mechanisms under fairness concerns of a green retailer. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2021, 59, 102361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, S.; Guan, X.; Chen, Y.J. Retailer information sharing with supplier encroachment. Prod. Oper. Manag. 2018, 27, 1133–1147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alba, J.; Lynch, J.; Weitz, B.; Janiszewski, C.; Lutz, R.; Sawyer, A.; Wood, S. Interactive home shopping: Consumer, retailer, and manufacturer incentives to participate in electronic marketplaces. J. Mark. 1997, 61, 38–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.Y.; Klassen, R.D. Drivers and enablers that foster environmental management capabilities in small- and medium-sized suppliers in supply chains. Prod. Oper. Manag. 2008, 17, 573–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Zhao, Q.; Zhao, X. Manufacturer’s product choice in the presence of environment-conscious consumers: Brown product or green product. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2019, 57, 7423–7438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moser, A.K. Consumers’ purchasing decisions regarding environmentally friendly products: An empirical analysis of German consumers. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2016, 31, 389–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, B.; Manrai, A.K.; Manrai, L.A. Purchasing Behaviour for Environmentally Sustainable Products: A Conceptual Framework and Empirical Study. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2017, 34, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheung, M.F.Y.; To, W.M. An extended model of value-attitude-behavior to explain Chinese consumers’ green purchase behavior. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2019, 50, 145–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simanjuntak, M.; Nafila, N.L.; Yuliati, L.N.; Johan, I.R.; Najib, M.; Sabri, M.F. Environmental care attitudes and intention to purchase green products: Impact of environmental knowledge, word of mouth, and green marketing. Sustainability 2023, 15, 5445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yenipazarli, A.; Vakharia, A. Pricing, market coverage and capacity: Can green and brown products co-exist. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2015, 242, 304–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Zhao, Q.; Zhao, X.; Tang, L. On the introduction of green product to a market with environmentally conscious consumers. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2020, 139, 106190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agi, M.A.N.; Yan, X. Greening products in a supply chain under market segmentation and different channel power structures. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2020, 223, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamali, M.B.; Rasti-Barzoki, M. A game theoretic approach for green and non-green product pricing in chain-to-chain competitive sustainable and regular dual-channel supply chains. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 170, 1029–1043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, C.; Liu, Q.; Shen, B. To be or not to be green? Strategic investment for green product development in a supply chain. Transp. Res. Part E Logist. Transp. Rev. 2019, 131, 193–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basiri, Z.; Heydari, J. A mathematical model for green supply chain coordination with substitutable products. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 145, 232–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, B.; Cao, Y.; Xu, X. Product line design and quality differentiation for green and non-green products in a supply chain. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2020, 58, 148–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raza, S.A.; Govindaluri, M.G. Pricing strategies in a dual-channel green supply chain with cannibalization and risk aversion. Oper. Res. Perspect. 2019, 6, 100118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosseini-Motlagh, S.M.; Ebrahimi, S.; Jokar, A. Sustainable supply chain coordination under competition and green effort scheme. J. Oper. Res. Soc. 2019, 6, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heydari, J.; Govindan, K.; Basiri, Z. Balancing price and green quality in presence of consumer environmental awareness: A green supply chain coordination approach. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2021, 59, 1957–1975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, B.; Choi, T.M.; Chan, H.L. Selling green first or not? A Bayesian analysis with service levels and environmental impact considerations in the Big Data Era. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2019, 144, 412–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ingene, C.A.; Parry, M.E. Mathematical Models of Distribution Channels; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Li, K.; Liu, X.Y.; Jacobson, D. Information and profit sharing between a buyer and a supplier: Theory and practice. Manag. Decis. Econ. 2018, 39, 79–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, B.; Zhang, H.; Gao, Y.; Liu, Z. Blockchain adoption and channel selection strategies in a competitive remanufacturing supply chain. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2022, 175, 108829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, Y.; Yang, T.; Yu, H.; Zhong, S.; Xie, W. Impacts of blockchain technology with government subsidies on a dual-channel supply chain for tracing product information. Transp. Res. Part E Logist. Transp. Rev. 2023, 171, 103032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desai, P.; Koenigsberg, O.; Purohit, D. Strategic decentralization and channel coordination. Quant. Mark. Econ. 2004, 2, 5–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arya, A.; Mittendorf, B. Enhancing vertical efficiency through horizontal licensing. J. Regul. Econ. 2006, 29, 333–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, M.; Dong, C.; Cheng, T.C.E. Quality disclosure strategies for small business enterprises in a competitive marketplace. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2018, 270, 218–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Li, Y.; Ma, Y. Direct selling, agent selling, or dual-format selling: Electronic channel configuration considering channel competition and platform service. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2021, 157, 107368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.Y.; Fan, R.; Shen, L.; Jin, M. Decisions and coordination of green e-commerce supply chain considering green manufacturer’s fairness concerns. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2020, 58, 7471–7489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Zhang, S.; Jia, F.; Wu, Z. Channel competition and coordination of E-commerce platforms under low-carbon environment: A cooperative game approach. Math. Probl. Eng. 2022, 3, 3595327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, K.; Su, Y.; Xu, Y.; Guo, Q. Channel selection for retailers in platform economy under cap-and-trade policy considering different power structures. Electron. Commer. Res. Appl. 2022, 56, 101205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, D.; Xiao, T.; Huang, J. Dual-channel structure choice of an environmental responsibility supply chain with green investment. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 210, 134–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, H.; Duan, Y. Online channel structures for green products with reference greenness effect and consumer environmental awareness (CEA). Comput. Ind. Eng. 2022, 170, 108350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, P.; He, Y.; Shi, C. Retailer’s channel structure choice: Online channel, offline channel, or dual channels. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2017, 191, 37–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Author | Product Types | Selling Channels | Key Factors | Products Competition | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Brown Products | Green Products | Direct Selling | Agent Selling | Green Demand Scale | Consumer Preference | ||

| Ranjan and Jha [15] | √ | √ | √ | √ | |||

| Wang and Song [16] | √ | √ | √ | √ | |||

| Zhang et al. [17] | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | ||

| Zhang et al. [21] | √ | √ | √ | ||||

| Yenipazarli and Vakharia [26] | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | ||

| Zhang et al. [27] | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | ||

| Agi and Yan [28] | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | ||

| Jamali and Rasti-Barzoki [29] | √ | √ | √ | ||||

| Basiri and Heydari [31] | √ | √ | √ | √ | |||

| Shen et al. [32] | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | |

| Raza and Govindaluri [33] | √ | √ | √ | √ | |||

| Hosseini-Motlagh et al. [34] | √ | √ | √ | √ | |||

| Heydari et al. [35] | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | ||

| Shen et al. [36] | √ | √ | √ | ||||

| Zhang et al. [44] | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | ||

| Yang et al. [48] | √ | √ | √ | ||||

| Zhou and Duan [49] | √ | √ | √ | √ | |||

| Our work | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ |

| Notation | Description |

|---|---|

| Decision Variables | |

| ) selling channel | |

| ) selling channel | |

| ) selling channel | |

| ) selling channel | |

| Sales cost per unit of green product through the direct selling channel | |

| Unit production costs of brown products | |

| Unit production costs of green products | |

| Proportion of green consumers in the market | |

| Preference coefficient of green consumers for brown products | |

| Preference coefficient of green consumers for green products | |

| Demand of brown products | |

| Demand of green products |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hu, H.; Cao, Y.; Yi, D.; Li, Q. How to Distribute Green Products in Competition with Brown Products? Direct Selling versus Agent Selling? Sustainability 2023, 15, 10961. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151410961

Hu H, Cao Y, Yi D, Li Q. How to Distribute Green Products in Competition with Brown Products? Direct Selling versus Agent Selling? Sustainability. 2023; 15(14):10961. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151410961

Chicago/Turabian StyleHu, Hanli, Yu Cao, Dan Yi, and Qingsong Li. 2023. "How to Distribute Green Products in Competition with Brown Products? Direct Selling versus Agent Selling?" Sustainability 15, no. 14: 10961. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151410961

APA StyleHu, H., Cao, Y., Yi, D., & Li, Q. (2023). How to Distribute Green Products in Competition with Brown Products? Direct Selling versus Agent Selling? Sustainability, 15(14), 10961. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151410961