Abstract

Social networking has opened up new avenues for learning and knowledge sharing. Because of its document exchange, virtual communication, and knowledge production capabilities, social media is a helpful tool for learning and teaching. This research embraces multiple goals. First, this study examines Bangladeshi university students’ social value, communication and collaboration, trust, and the perceived benefits of knowledge sharing through social media in academic advancement. The second goal is to examine how families and technology support mediate those aspects of social media knowledge sharing with student academic development. This study uses the Technology Acceptance Model and Social Exchange Theory as an example of how knowledge sharing through social media with the help of family and technology impacts academic progress among Bangladeshi university students. This paper uses PLS-SEM on the survey data from 737 Bangladeshi students to test the model with the help of SmartPLS 4. Social value, communication and collaboration, trust, and the perceived benefits of sharing knowledge through social media significantly enhance Bangladeshi students’ academic growth. In the case of mediation, family and technological support mediate the relationship between communication and collaboration, trust, perceived benefits and academic development. However, there is no mediation between the social value of knowledge sharing in social media and students’ academic development. The article concludes with implications, limitations, and future research.

1. Introduction

The increasing global focus on advanced social media (SM) tools results from their widespread use and positive impact on society. The rapid evolution of this media form has transformed how people share knowledge, interact, and collaborate, particularly in work-related discussions [1]. Social media platforms encompass various online communities for word-of-mouth communication, such as social networking sites (SNS) such as Myspace and Facebook, microblogs such as personal blogs or Twitter, photo- or video-sharing services such as Flickr and YouTube, and collaborative websites such as Wikipedia [2]. These platforms have become well-established venues for building knowledge sharing (KS) networks, connecting people with similar interests, and facilitating the exchange of ideas [3].

In academic institutions, there is a growing demand for high-quality materials and expertise, making knowledge sharing a challenging task [4]. In addition, the advancement of telecommunications, the Internet, and the World Wide Web has expanded the opportunities for online applications. The rise of social networking sites (SNS) has mainly driven the development of web applications in the past decade. Platforms such as Myspace, Facebook, LinkedIn, Twitter, Flickr, Instagram, and WhatsApp have enabled individuals to share their expertise and experiences, create profiles, interact, and collaborate [5]. According to the Global Digital Report 2019, 3.484 billion people use social media, with an annual growth rate of 9%.

To meet the expectations of faculty members, academic institutions need to align their human resource practices, policies, and processes with a focus on integrating knowledge sharing into the organizational culture and removing barriers to its implementation [6]. For example, research conducted by Patel et al. (2013) [7] demonstrated the support provided by intelligent communities and social networking sites (SNS) to teachers and students. Their findings indicated that out of 226 participants, 163 used social networking for educational purposes. Additionally, recent studies have explored how social networking sites assist students and professionals [8].

Sabbir Rahman (2014) [9] researched KS among undergraduate and graduate students at private institutions in Bangladesh. Based on data acquired from 350 respondents at various private universities, graduate and undergraduate students communicate knowledge in very different ways. Overall, this study demonstrated that postgraduate students have greater reported attitudes toward sharing knowledge than undergraduate students. Islam et al. (2013) [10] studied faculty members’ knowledge sharing patterns in Bangladesh. Thus, there are numerous research works on KS around the world, including Bangladesh. In addition, Haque and Islam (2018) [11] studied knowledge sharing from the pharmaceutical industry perspective; Rubel et al. (2021) [12] and Jilani et al. (2020) [13] researched it in the garment industry in Bangladesh. In contrast, Islam et al. (2015) [14] studied Bangladeshi library professionals’ knowledge sharing, while Rahman et al. (2018) [15] investigated knowledge sharing behavior among the academic staff. Interestingly, a recent study was conducted by Rahman et al. (2022) [16] on public university students’ perceptions of the changed knowledge sharing system during the pandemic in Bangladesh. According to the findings, most public university students come from poor or lower-middle-class households and lack access to mobile devices and the Internet, which hinders online instruction. The survey found that most students are comfortable with the changed knowledge sharing structure owing to the pandemic. Online knowledge sharing networks improved students’ technical efficiency. The study also revealed significant institutional attempts to alter knowledge sharing networks during the pandemic. Changing knowledge sharing mechanisms have hurt students’ mental health. Thus, modifying the knowledge sharing method during the pandemic has not improved learning. Another study conducted by Rahman and Mithun (2021) [17] on Bangladeshi university students’ social media use and its effect on their academic performance found a positive relation between variables.

However, there are many studies that have concentrated on KS factors and organizational and educational setting performances [18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30]. Usman and Oyefolahan (2014a) [31] showed how the availability and assistance of technology have a big impact on knowledge sharing. Usman and Oyefolahan (2014b) [31] accepted the arguments in favor of promoting technology competence to improve knowledge exchange within universities, which might result in innovation inside universities. Additionally, they offered a variety of approaches to using technology to promote knowledge sharing across institutions, including cooperation, communication, awareness, training and development, motivation, and learning facilities. Numerous colleges are using cutting-edge technology, such as Web 2.0 tools and portals, to improve knowledge exchange, which in turn increases creativity. Enhancing communication and collaboration between instructors, students, and university administration is the main goal of the portal development [32,33], which may foster innovation in higher education institutions. According to Zeraati et al. (2020) [34], proficiency with technology is crucial in providing students with a high-quality education.

Despite the increasing awareness of the importance of knowledge sharing, there is a dearth of empirical studies on this topic in developing countries such as Bangladesh with the student’s family and technology as means of mediation. Bangladesh’s Internet and digital technology use have grown rapidly in recent years. Bangladesh has 66.94 million Internet users in 2023, a tremendous growth rate [35]. Social media platforms have proliferated with Internet penetration, providing a perfect chance to study student knowledge exchange in this digital context. Bangladesh’s socioeconomic growth depends on education. To meet development goals, the government is expanding and improving education. Studying growth in academia, especially in relation to social media and technology, can help enhance educational outcomes and the nation’s overall development. Public universities in Bangladesh allow academics to investigate a varied student body that reflects the country’s socioeconomic diversity. Public universities are more accessible to diverse students, making education more inclusive. Public universities in Bangladesh are the foundation of higher education, making them ideal for studying the academic growth nexus. Bangladeshis value family. Parents often influence their children’s educational and employment choices. This substantial family effect provides an excellent scenario to explore the mediating function of family support in the social media-driven sharing of knowledge and academic progress. Social media literacy and digital abilities may affect knowledge sharing and academic growth. Social media and technology-savvy students may be better at sharing knowledge and achieve more academic success. Thus, examining the importance of digital skills and literacy in this context may help educators and policy makers. Currently, there is a research gap in the area of knowledge sharing behavior in Bangladesh that needs to be addressed.

The objectives of this research are twofold. First, we identify and examine the relationship between different factors that affect students’ knowledge sharing in social media that enhance academic development. Second, we explore the mediating effects of family and technological support in social media knowledge sharing to enhance academic development.

2. Literature Review

Knowledge refers to acquiring and utilizing information, accompanied by ability [36,37]. It can be categorized in several ways, including personal, shared and public, hard and soft, practical and theoretical, forefront and backdrop, and internal and external [38]. However, the primary division lies in explicit knowledge (EK) and tacit knowledge (TK) [39]. TK, constituting around 80% of total knowledge, represents a direct experience that cannot be easily documented in artefacts, while EK makes up the remaining 20% [40]. On the other hand, EK can be conveyed through formal and systemic language, codified using various data forms, and recorded in detailed documents. It is factual, logical, and represented in words, numbers, or formulas, allowing for processing and dissemination through technology [41,42,43,44].

Knowledge sharing encompasses various definitions provided by scholars. Some studies consider knowledge sharing, knowledge flows, and knowledge transfer interchangeable concepts. For instance, Alavi and Leidner (2001) [36] defined knowledge sharing as disseminating knowledge within an organization. Park and Im (2003) [45] described it as the transfer of knowledge from one person to another within an organization. Knowledge sharing is an intentional act that makes experience reusable for others [46]. Through sharing, individuals can exchange implicit or explicit knowledge, creating new knowledge [47].

As defined by Ishaya and Azamabel (2021) [48], social media refers to collaborative digital-mediated tools that facilitate the sharing, communication, and exchange of ideas, information, and various forms of expression through virtual networks. In the twenty-first century, social media has become an integral part of human existence, with its usage widespread across the globe. In 2020, approximately 3.06 billion individuals from diverse backgrounds actively engaged with at least one social media platform in their daily lives, and this number is projected to reach 4.4 billion by 2025. Popular platforms include WeChat, Facebook, Twitter, Weibo, WhatsApp, and Instagram. Furthermore, the uploading of study-related materials by students on social media platforms is recognized as a reliable source of information that holds significance for various communities, such as students, consumers, and workers [49,50,51].

Academic performance refers to how students approach their studies and handle assigned tasks. It is commonly evaluated through cumulative GPA, which reflects class and subject achievements [29,52]. Assessing academic performance can involve measuring the cumulative grade point average (CGPA) based on previous examinations [53] and considering research papers as indicators of academic achievement. Additionally, creating new knowledge and effective presentations within the classroom and among peers can contribute to academic soundness. In educational settings, various active and collaborative learning strategies are employed to maximize classroom time and help students apply what they have learned. Online environments may utilize weekly assignments and discussion posts to engage students outside the classroom and reinforce practical application. While technology and social media enable knowledge creation and sharing, the support of educators is still necessary in certain situations. Therefore, it is beneficial to integrate technology with traditional teaching methods, leveraging the vast potential of technology alongside the skills of instructors to provide a comprehensive and exceptional learning experience for students at all educational levels, including both public and private universities [29].

3. Theoretical Frameworks

The conceptual relationships proposed in this study are grounded in well-established theories, which form the basis for these relationships. In addition, extensive research has put forth various hypotheses exploring the link between knowledge sharing and students’ academic achievement. This conceptual study considers the theories of the Technology Acceptance Model (TAM) and Social Exchange Theory (SET), which support the conceptual framework.

3.1. Technology Acceptance Model

Fred Davis, a professor at the MIT Sloan School of Management, proposed the Technology Acceptance Model (TAM) in 1985 to examine users’ adoption of computer technology [54]. According to Davis, system utilization can be predicted based on the user’s stimulus, which is influenced by external factors and the system’s capabilities and structure [55]. The TAM was derived from the theory of reasoned action (TRA), a well-known social psychology theory that explains individual actions by considering underlying motivations [56]. Davis (1989) [54] adapted TRA by deconstructing the attitude construct into two key concepts: perceived usefulness (PU) and perceived ease of use (PEU), which determine the acceptance of and usage behavior toward new technology. The concept of perceived effectiveness reflects an individual’s belief that using a particular technology will enhance their work performance, while perceived simplicity of use refers to the ease with which an individual expects to use the technology. In addition to these variables, some studies have identified external factors such as perceived satisfaction, which is consistently associated with the core constructs of TAM and positively influences the intention to use technology [57,58]. Over time, the TAM has emerged as a prominent model for explaining and predicting technology usage [54].

Based on the TAM theory, the independent variables influencing students’ adoption of social media for educational purposes are social value, communication and collaboration, trust, and the perceived benefits of knowledge sharing. Social value represents the extent to which individuals perceive using social media for educational purposes as valuable for their academic development. Communication and collaboration reflect individuals’ beliefs about the ability of social media to facilitate academic communication and collaboration with peers. Trust pertains to individuals’ confidence in the reliability and security of using social media for educational activities. Finally, the perceived benefits of knowledge sharing in social media encompass individuals’ perceptions of the advantages gained through sharing knowledge in this context.

According to Gao and Bai (2014) [59], peer, family, and media social influence (SI) have a significant impact on individuals’ inclination to adopt specific technologies. SI refers to the extent to which individuals believe that significant others endorse using a new system. Rahman et al. (2018) [15] and Venkatesh et al. (2003) [60] supported the notion of SI as a crucial factor in technology adoption. Schmidthuber et al. (2020) [61] found a positive relationship between societal impact and customers’ intentions to use mobile payments. However, in this study, family and technological support were considered influences from the family that encouraged greater utilization of social media for knowledge sharing and subsequent academic development. Family and technological issues can mediate the relationship between perceived ease of use and students’ academic development. Students with access to reliable technology and Internet connections are more likely to share knowledge on social media platforms. Support from the family, such as parental monitoring and financial assistance for social media use, can also positively influence students’ adoption of social media for educational purposes. These factors facilitate the ease of using social media and contribute to students’ academic development.

According to this theoretical framework, the combined influence of social value, communication and collaboration, trust, and perceived benefits will impact students’ academic development. These independent variables play a significant role in shaping the learner’s growth. Furthermore, the relationship between these variables and academic development is mediated by the support provided by family and technology. Family assistance and technological resources act as intermediaries, facilitating the impact of the independent variables on students’ academic progress.

3.2. Social Exchange Theory

The Social Exchange Theory was initially developed in the 1950s to analyze human behavior and resource trading [62]. This theoretical framework, as proposed by Blau, provides insights into understanding knowledge sharing behavior in the context of using social media for academic development. According to Cropanzano and Mitchell (2005) [63], the Social Exchange Theory suggests that social behavior is the outcome of an exchange process between two parties, with each party aiming to maximize their rewards while minimizing costs.

In the context of students’ academic development, the Social Exchange Theory posits that their engagement in knowledge sharing behaviors through social media is influenced by their perception of receiving benefits such as improved academic performance or enhanced knowledge and the perceived low costs of sharing. According to the theory, students are more inclined to share knowledge when they believe it will result in benefits such as academic improvement and increased knowledge. Moreover, the Social Exchange Theory proposes that the family and technological support can act as mediators in the relationship between knowledge sharing behavior and academic development. This is due to the facilitation of communication and collaboration enabled by family and technological support.

The support received from families can significantly impact students’ inclinations to share their acquired knowledge. Family support may manifest through encouragement, providing access to resources and creating an environment conducive to learning and collaboration. Furthermore, technological support is crucial in facilitating knowledge sharing by granting students access to a reliable Internet connection, computers, and relevant software. This type of support eases the sharing of knowledge and reduces the associated costs.

According to this research, knowledge sharing is conceptualized as a form of social exchange that is influenced by an individual’s social value orientation. In this social exchange, sharing knowledge incurs costs for the knowledge owner while providing benefits to the recipient, which subsequently influences the willingness to share information. The study also suggests that social value orientation plays a role in shaping knowledge sharing behavior, as it reflects an individual’s beliefs or attitudes toward the outcomes of sharing. The concepts of social value, trust, perceived benefits, collaboration, family, and technological issues align with the findings of Cyr and Choo (2010) [64], Assegaff and Dahlan (2011) [65], and Al-Rahimi et al. (2013) [66].

3.3. Social Value of Knowledge Sharing in Social Media and Academic Development

The role of social values in service quality and knowledge dissemination was highlighted by Rogers (1962) [67] and Robertson (1967) [68] in their research on opinion leadership and diffusion of technologies [69]. Interpersonal contact and knowledge dissemination have a significant impact on social values. With social media’s prevalence, interpersonal communication and knowledge exchange have become highly feasible [70,71]. José-Cabezudo and Camarero-Izquierdo (2012) [72] found that the strength of a social connection tie, whether weak or strong, plays a crucial role in the relationship between knowledge sharing and its antecedents in social media. Employees use social media to build relationships and interaction [73]. Successful knowledge sharing among coworkers requires effective communication and relationship building [74]. Social media platforms simultaneously promote social and academic relationship building, ultimately impacting academic performance in the educational setting. These platforms allow researchers to share stories, collaborate on projects, and stay updated on recent research developments, fostering new partnerships and collaborations. Social value is predicted to influence students’ knowledge sharing behaviors [75]. Fiske’s Relational Model Theory (RMT) concept (1992) [76] suggests that humans are inherently social beings, a belief supported by research [77]. The RMT helps us understand the dynamics of interpersonal relationships and how they influence individual behavior. According to the RMT, individuals tend to engage in cooperative behavior, experience the joy of helping others, and derive a sense of fulfillment when they have strong relationships. These factors contribute to their willingness to take positive actions.

3.4. Communication and Collaboration and Students’ Academic Performance

According to Analoui et al. (2014) [78], knowledge holds significant value for every organization. When individuals share newly gained information with others in an organization, it is referred to as a knowledge sharing activity [79]. Communication involves human contact through oral communication and body language, and social networking in the workplace plays a crucial role in enhancing communication and promoting knowledge transfer [80].

Collaboration and communication are vital for the success of organizations, educational institutions, and individuals in academic and research settings [6,81,82,83]. Through effective collaboration and communication, knowledge can be shared among students. In the context of the 21st century, collaborative learning, contact with others, and displayed learning are essential aspects [84,85]. Al-rahmi et al. (2015) [86] emphasized that collaborative learning through social media channels such as Facebook, email, and Twitter facilitates learning and information sharing among students, instructors, and trainers in real-life scenarios and experiences. Social media platforms positively impact collaborative learning, including contact with colleagues, supervisor interaction, participation, perceived ease of use, and perceived usefulness.

Social media resources enable individuals to engage in social activities, build intimate relationships with friends, and navigate a new social world [87,88]. Within an academic environment, these social technologies are used to connect and collaborate with faculty and students [89]. Increased communication facilitated by social media can help students improve their overall performance, engage in classroom discussions, and integrate with peers [90]. Social media platforms serve as dynamic tools to foster the development of learning environments by encouraging collaboration and communication among students, thereby enhancing their learning behavior and performance.

3.5. Trust of Knowledge Sharing in Social Media and Academic Development

Trust, as defined by Gambetta (2000) [91] and Riegelsberger et al. (2003) [92], is the act of being open to individuals based on a good recognition of the consequences of their behavior. When individuals trust each other, they are more likely to take risks, knowing that the other party will not harm them. Dyer and Singh (1998) [93] found that trust is a cost-effective method for enhancing organizational knowledge exchange. Trust facilitates knowledge sharing among members of an organization and promotes cooperation [94]. Trust plays a central role in every organizational interaction [95], and several studies [96,97] have demonstrated the influence of trust on knowledge sharing.

The consensus among scholars is that trust is a psychological state characterized by a willingness to be vulnerable based on positive expectations about another person’s intentions or behavior [98]. Trust is a powerful and cost-effective motivator for individuals to share their unique expertise. It establishes and maintains trade relationships that facilitate sharing of high-quality information [99], ultimately leading to effective knowledge sharing. When individuals trust each other, they are less concerned about negative consequences and more willing to share their expertise [100].

3.6. Perceived Benefit of Knowledge Sharing in Social Media and Academic Development

In light of the benefits and individual outcomes associated with knowledge exchange, promoting knowledge sharing via social media networks becomes essential within organizations [101]. The expectations of perceived rewards, such as respect, recognition, moral responsibility, and pleasure, are crucial in influencing individuals’ participation in social phenomena [37,62]. Moreover, personal and societal values also impact individuals’ willingness to continuously share their expertise [102], as these values guide the flow of information within an organization. Participants’ perceptions of the advantages of knowledge sharing significantly influence their willingness to share knowledge [64].

Previous studies, such as Constant et al. (1996) [103], have shown that participants in extra-organizational electronic networks often perceive themselves as part of a larger group than they are.

3.7. Academic Development

Academic performance may be assessed using academic and non-academic criteria, such as extracurricular activities. Higher education aims to increase students’ academic performance, general education knowledge, and talents such as critical thinking, moral growth, community social skills, and psychological maturity. Academic performance refers to how students approach their studies and how they cope with or complete the tasks assigned by their teacher. Academic success is commonly assessed by cumulative GPA, linked to class and subject area accomplishment, according to Junco (2015) [52]. Thus, academic performance can be measured by one cumulative grade point average (CGPA) [53] in the previous examinations. In addition, several research papers can be indicators of academic performance. New knowledge creation and good presentation within the classroom and among fellows can also be considered academic soundness. At school, various active and collaborative learning tactics may be used to optimize the limited classroom time and help students comprehend how to apply what they have learned.

Sharabati (2018) [104] looked at the factors that influence knowledge sharing on an online social network (particularly Facebook) and how they affect students’ academic achievement in the classroom. The survey included 60 undergraduate students from Palestine Technical University enrolled in accounting basics programs. The structural equation model was used to determine what variables would encourage these students to share their expertise on Facebook for educational reasons. The findings suggested that altruism and knowledge self-efficacy motivate students to share their information on Facebook, but trust and reputation do not. Furthermore, the findings of this research indicated that knowledge sharing via social media significantly influences students’ academic achievement. Because the elements influencing students’ knowledge sharing vary across persons and circumstances, future studies might look into the influence of gender, age, education level, and topic disparities in social network involvement.

3.8. Family and Technological Support (FT) as the Mediating Role

Technology facilitates knowledge sharing through various channels and means in the digital era. Two critical technological considerations are the availability of IT infrastructure and the utilization of social media platforms [105]. On the other hand, insufficient technological infrastructure and information systems pose significant risks to internal knowledge sharing within organizations [106].

There is a digital divide between individuals in developed countries with advanced access to information and communication technology (ICT) and those in developing countries with limited or no access to such technologies [107]. This divide is observed between countries and within countries where disparities in access and usage of ICT exist across regions [108]. Efforts to bridge this digital divide have been proposed and implemented [109]. However, in the case of Bangladesh, the country needs to catch up in bridging the digital divide compared to other underdeveloped nations because of the lack of concerted efforts. A proper institutional and legal framework and relevant laws or acts have helped progress in this area. The Bangladesh Telecom Regulatory Commission (BTRC) holds jurisdiction over managing and controlling the country’s telecom industry, which is crucial for ICT deployment but faces conflicting powers and authority. Although Bangladesh is progressing in various ICT aspects, it is at a different pace than developed countries. Ensuring accessibility to ICT for people at all levels is essential for its effective development. Bangladesh has been increasing its workforce in the ICT sector through educational institutions and training programs. However, it is essential to ensure the quality of these programs and adapt them as needed. Expansion of ICT services should not be limited to major cities and districts but should reach all levels, including grassroots. The establishment of digital exchanges and the extension of transmission linkages at the upazilla level, along with the development of optical fiber cable infrastructure, are steps taken to provide nationwide ICT services. Bangladesh has also established undersea cable connections to the global information superhighway, but proper planning and utilization of these connections are necessary to maximize their benefits. Content creation, application development, and business opportunities must be explored to fully leverage the available bandwidth.

Parenting styles have been found to influence the academic success of teenagers, regardless of their educational level. Parents play a significant role in shaping their teenagers’ social and educational lives and can contribute to their success in school and life [110]. Family intervention can be a crucial factor in creating a supportive educational development environment, including using social media for knowledge sharing. Furthermore, research has highlighted how technology can facilitate the exchange of existing information. Information technology is considered a critical enabler of knowledge management, particularly in the context of developing a knowledge-based economy. Information and communication technologies (ICTs) are essential for the efficient accumulation, compilation, storage, and dissemination of data, reducing the cost of sharing codified knowledge compared to implicit knowledge [111].

Based on the above considerations, this study hypothesizes the following relationships:

H1.

There is a significant positive relationship between students’ social value of knowledge sharing in social media and their academic development.

H2.

The mediating role of family and technological support exists in the relationship between the social value of knowledge sharing on social media and academic development.

H3.

A significant positive relationship exists between communication and collaboration in knowledge sharing through social media and students’ academic development.

H4.

The mediating role of family and technological support exists in the relationship between communication and collaboration in knowledge sharing on social media and students’ academic development.

H5.

A positive relationship exists between trust in knowledge sharing on social media and academic development.

H6.

The mediating role of family and technological support exists in the relationship between trust in knowledge sharing on social media and academic development.

H7.

There is a significant positive relationship between the perceived benefits of knowledge sharing in social media and academic development.

H8.

The mediating role of family and technological support exists in the relationship between the perceived benefits of knowledge sharing on social media and academic development.

H9.

There is a positive relationship between students’ families and technological support for knowledge sharing on social media and academic development.

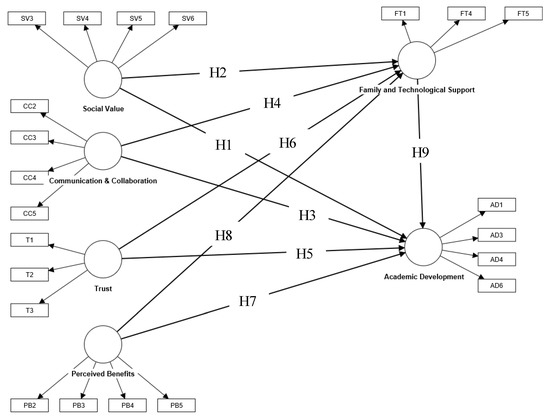

This research proposes the following model (Figure 1) based on the above discussion.

Figure 1.

Theoretical Framework of Knowledge Sharing in Social Media and Academic Development.

4. Methods

When designing a research study, several factors need to be considered, including the purpose of the study, the type of study, the unit of analysis, the time horizon, the level of researcher control and manipulation, the data collection process, measurement of variables, and data analysis [112].

4.1. Sampling and Measurement

According to the University Grants Commission, in 2020, 4,690,876 students studied in 153 universities in Bangladesh, and in 2021, the number of students studying in 158 universities in Bangladesh was 4,441,717. Currently, there are 54 public and 112 private universities in Bangladesh [113]. This research study focused specifically on students from public universities in Bangladesh. Public universities in Bangladesh operate independently and are categorized into agricultural universities, engineering universities, general universities, medical universities, science and technology universities, and specialized institutions [113].

This study aimed to examine the knowledge sharing practices on social media and their effect on the academic progress of university students. Data for this study were collected through a survey questionnaire, utilizing both online and offline modes of data collection. According to Kemp (2023) [35], as of 31 December 2022, Bangladesh ranked as one of the top three countries contributing to the growth of Facebook’s active user base, making it a great location for study. Bangladesh had 66.94 million Internet users at the beginning of 2023, when Internet penetration was 38.9%; therefore, this can serve as a valuable lesson for other developing nations where social media knowledge sharing is expanding. Because of the COVID-19 situation, the survey was primarily conducted online using Google Forms. The survey was made available online between January 2022 and August 2022.

The questionnaire consisted of two sections. The first section gathered basic personal information from the respondents, including gender, age, place of residence, and the last cumulative grade point average (CGPA) obtained. The second section of the survey focused on the respondents’ perspectives on knowledge sharing on social media and its impact on their academic performance. All survey items were adapted from previously validated measures and were scored on a five-point Likert scale, ranging from one (strongly disagree) to five (strongly agree). Using convenience sampling techniques, researchers initially targeted approximately 800 data because complex models with numerous latent variables or paths may require a larger sample size to ensure stable and reliable estimates. Thus, the questionnaire was initially distributed via Facebook messaging to 600 students from various public educational institutions in Bangladesh. However, in addition to sophisticated statistical tool requirements, the researcher visited classrooms at multiple universities and sent the questionnaire via Messenger to the class groups, requesting that they complete the Google Form. Students were also asked to distribute the questionnaire to their friends attending other Bangladeshi public universities. Out of the total 600 Google Forms sent out, 437 came back with responses. In addition, researchers collected another 300 data offline via face-to-face questioning. Consequently, 737 responses were gathered for analysis. Email was initially considered but later discarded, as getting the email addresses posed to be a difficult task because many students did not use emails as much as Messenger.

Among the participants, 63% identified as male, while 37% identified as female. Most of the respondents (88%) were 18–25 years old, indicating a predominance of young adults. In terms of academic level, the study revealed that 50% of the students were at the undergraduate level, 45% were at the master’s level, 3% were at the MPhil level, and 2% were at the PhD level. This distribution suggests a higher representation of students at the undergraduate and master’s levels.

The study also provided insights into the students’ social media usage patterns. Most (80%) reported spending 2–4 h daily on social media. Among the specific platforms, Facebook was the most popular, used by 93% of the students. A total of 70% of the students used YouTube. Additionally, 50% of the students used WhatsApp, while 20% used Google Scholar and 10% used ResearchGate, among other platforms.

4.2. Data Analysis

Regarding the research methodology, the current study aligns with the positivist paradigm, which emphasizes the development of solid theoretical frameworks that are rigorously tested. Structural Equation Modeling (SEM), a sophisticated statistical approach combining Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) with a structural model, was employed for data analysis using SmartPLS 4. SEM allows for examining interrelationships among variables based on a priori theoretical assumptions and is particularly useful for hypothesis testing and inferential data analysis. SEM is particularly useful when dealing with complex models that involve multiple latent variables and observed variables. It allows researchers to estimate the impact of latent variables on the dependent variable(s) and make predictions based on the model’s relationships and also enables researchers to explore mediating and moderating effects within a model. Additionally, it facilitates the comparison of models across different groups or sub-samples, and researchers can assess whether the relationships between variables differ based on demographic factors or other grouping variables. It enables the modeling of interactions between multiple predictor and criterion variables and employs CFA to evaluate the fit of the hypothesized model to the actual data [112]. In addition, SEM is commonly used to assess causal correlations between variables, employing a linear equation system to evaluate the hypothesized model.

5. Results

This section examines the suitability of the data for the measurement models by assessing the fit of the structural and causal models based on established measurement models. The analysis involved path analysis and the evaluation of Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) and Structural Equation Modeling (SEM). In addition, reliability analysis, validity convergence, and data discrimination were conducted to determine whether the models were appropriate for further examination.

5.1. Level of Response Rate

While there are no universally established criteria for determining a high response rate, an 80% or higher response rate is generally considered outstanding. In addition, high response rates are desirable as they contribute to the validity, reliability, and generalizability of the study findings, particularly in survey and observational studies [114].

To increase response rates, it is recommended to use validated survey tools whenever possible and involve professionals in survey research to ensure the development of rigorous procedures. Using established survey instruments helps maintain accuracy and reliability, while developing new measurement instruments requires precision and sensitivity to avoid ambiguity and potential bias in the results [115].

In the current research study, 900 questionnaires were distributed, and 737 (82%) accurately completed questionnaires were returned to the researchers. Therefore, with an overall response rate of 82%, the study’s response rate was considered acceptable and provided a solid basis for analysis and interpretation. The response rate of 82% for the current research was therefore considered acceptable.

5.2. Variables and Items Used in the Study

In this study, we investigated the relationship between various variables, including social value, communication and collaboration, perceived benefits, trust, family and technology availability and use and students’ academic development. These variables have been adopted from various sources as shown in the Table 1.

Table 1.

Variables and Items Used in the Study.

6. Findings

6.1. Descriptive Statistics of Constructs

If a data array exhibits significant skewness or kurtosis, it is essential to demonstrate clearly that the data are regular using a histogram or numerical measures. A surface outlier is identified if the residual value exceeds −3.3 or +3.3. Skewness, or rather the lack of symmetry, is a measure of asymmetries. A distribution or data set is symmetric when it appears the same on the left and right sides of the middle. According to the normal distribution, kurtosis may be used to determine whether the findings are light-tailed or heavy-tailed. Positive numbers for the skewness indicate data that are skewed right, whereas negative values suggest data that are slanted left. Skewed left refers to the length of the left tail compared with the right tail. Like skewed left, skewed right indicates that the right tail is longer than the left one. The multimodality of the data may impact the skewness sign. The second definition also states that positive kurtosis denotes a “heavy-tailed” distribution while negative kurtosis denotes a “light-tailed” distribution. Data are not average if there is significant skewness and kurtosis. In other words, data sets with a high kurtosis look to contain many outliers or heavy tails. Data sets with low kurtosis are typically thin or emphasized. A uniform distribution would be the most severe scenario [130,131]. The mean and standard deviation of the analysis are shown in Table 2. Every item was calculated on a Likert scale of 5 points. All variables were above 3.2 on average. The 5-scale results indicated that most study constructs had a mean of more than 3.

Table 2.

Treatment of Outliers.

Table 3 presents the results of reliability analysis using Cronbach’s alpha and composite reliability, which assess the internal consistency of the observed items. The values in PLS-SEM are arranged based on the individual reliability level of each indicator [132]. Cronbach’s alpha and composite reliability range from 0 to 1, with higher values indicating higher reliability. In exploratory research, reliability levels between 0.60 and 0.70 are considered acceptable, while more advanced stages require values greater than 0.70 [133]. However, values exceeding 0.90 are not preferred, and values of 0.95 or above are considered poor [134].

Table 3.

Results of the Measurement Model.

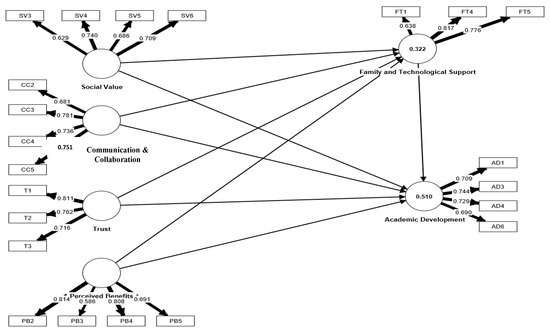

To assess the convergent validity of reflective variables, Average Variance Extracted (AVE) is used [135]. AVE measures the variation a construct explains compared to measurement error. It is a measure of convergent validity, indicating the degree of agreement between different indicators of the same construct. Convergent validity is evaluated using item factor loadings, composite reliability, and AVE. AVE and composite reliability range from 0 to 1, with higher values indicating better reliability. Convergent validity is confirmed when AVE is equal to or greater than 0.5. AVE represents the extent to which a latent concept explains the variation in its indicators, also known as commonality [133]. The construct’s component outer loadings must all be more than the recommended amount of 0.708% [136]. If the Average Variance Extracted (AVE) is more significant than 0.5 and the composite reliability (CR) is greater than 0.7, items with outer loadings between 0.40 and 0.70 can be retained [137]. The outer (factor) loadings, composite reliability (CR), and Average Variance Extracted (AVE) scores all matched the predetermined standards, as shown in Table 3. Figure 2 displays the SmartPLS output of the measurement model.

Figure 2.

Measurement Model Assessment.

6.2. Discriminant Validity Assessment Based on Heterotrait–Monotrait Ratio (HTMT) and Fornell–Larcker Criterion

In recent years, the Heterotrait–Monotrait Ratio of the Correlations (HTMT) approach has been introduced as a method to evaluate discriminant validity [137]. The HTMT ratio is calculated as the average of the heterotrait-hetero method correlations divided by the average of the monotrait-hetero method correlations. It provides a quantitative measure of the extent to which constructs differ from each other compared to their internal consistency. The HTMT (Table 4) approach offers a more rigorous assessment of discriminant validity by considering both the strength of relationships between constructs and the level of reliability within constructs [138]. Any study using latent variables must evaluate the discriminant validity to avoid multicollinearity problems. The most popular technique for this is the Fornell and Larcker criterion (Table 5), a new method for evaluating the discriminant validity, as Henseler proposed in 2015. This study’s findings supported the discriminant validity results reported in Table 4 and Table 5.

Table 4.

Discriminant Validity (Heterotrait–Monotrait Ratio (HTMT)).

Table 5.

Fornell–Larcker Criterion.

6.3. Structural Model

The coefficient of determination, commonly referred to as R squared, ranges from 0 to 1, with 1 indicating perfect predictive accuracy. The interpretation of R-squared values can vary across different disciplines, and there are no universally applicable guidelines for determining the level of predictive acceptance. However, Henseler et al. (2009) [139] proposed a rule of thumb stating that R-squared values of 0.75, 0.50, and 0.25 are considered substantial, moderate, and weak, respectively. Therefore, it is recommended that Q2 (Table 6) be greater than 0 [140,141].

Table 6.

Q and R squared.

Based on the findings presented in Table 6, the results indicated a moderate predictive accuracy of the mediating variables within the model and a medium accuracy of the dependent variable, academic development. The model accounted for 51% of the variance in student academic development, while family and technological support explained 32%.

6.4. f-Square

The impact size of the links between the constructs should be considered to examine the practical applicability of substantial effects. Independent of sample size, the effect size is a way to quantify the size of an effect. The f2 values between 0.020 and 0.150, 0.150 and 0.350, or more than or equal to 0.350, respectively, indicate a weak, medium, or high impact size [142]. Effect size values of less than 0.02 indicate that there is no effect. Table 7 shows the f-square of this study.

Table 7.

f-Square.

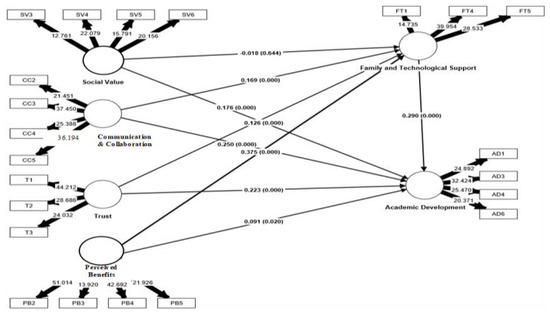

The path coefficients in the regression analysis and the standardized coefficients in the PLS-SEM were found to be comparable. The significance of the hypotheses was assessed using the β values and tested using the T-statistics. The significance of the hypothesis was assessed using the bootstrapping method. A bootstrapping approach was used to assess the significance of the path coefficient and T-statistics values using 5000 subsamples without significant changes. Table 8 presents the results of this investigation. This study employed a bootstrapping method with 5000 subsamples to evaluate the significance of the path coefficients and T-statistics values [142,143].

Table 8.

Path Coefficient of Model Hypothesis Test.

The findings in Table 8 and Figure 2 and Figure 3 confirmed the positive relationship between the social value of knowledge sharing in social media and students’ academic development (β = 0.176, T = 4.026, p < 0.000), supporting H1. However, family and technological support did not mediate the relationship between the social value of knowledge sharing and academic development; as a result, it was negative and insignificant (β = −0.018, T = 0.462, p = 0.644), leading to the rejection of H2.

Figure 3.

SmartPLS Output of the Structural Model Assessment.

The significant and positive influence of knowledge sharing in social media for communication and collaboration on students’ academic development (β = 0.250, T = 5.918, p < 0.000) provided robust support for H3. Additionally, the direct influence of communication and collaboration on family and technological support was also found to be positive and significant (β = 0.169, T = 3.551, p < 0.000), supporting H4.

The influence of trust on knowledge sharing through social media and students’ academic development was found to be significant (β = 0.223, T = 6.475, p < 0.000), supporting H5. Additionally, family and technological support were found to mediate the relationship between trust and academic development, with a significant positive effect (β = 0.126, T = 4.470, p < 0.000), confirming H6.

The relationship between perceived benefits and academic development was found to be significant (β = 0.091, T = 2.330, p < 0.020), providing support for H7. Furthermore, the mediating role of family and technological support in the relationship between perceived benefits and academic development was strongly supported (β = 0.375, T = 8.819, p < 0.000), confirming H8. The significant effect of family and technological support on students’ academic development was also established (β = 0.290, T = 6.354, p < 0.000), confirming H9.

The greater the beta coefficient (β), the stronger the effect of an exogenous latent construct on the endogenous latent construct [143].

Table 8 and Figure 2 and Figure 3 present the path coefficients in the model. The construction-related factor exhibited the highest path coefficient of β = 0.375, indicating its strong impact on family and technological issues and academic development. On the other hand, the external-related factor had a negative effect on academic development with a path coefficient of β = −0.018. The graphical representation in Figure 2 and Figure 3 illustrates all the path coefficients in the model.

Table 3 and Table 8 presents the correlation coefficients between the latent endogenous and exogenous variables, revealing significant associations between them. Through a comprehensive analysis of the measurement and structural models, the validity of both theories was established. Eight out of nine hypotheses were found to be statistically significant and accepted. These findings provided a comprehensive and accurate understanding of the factors influencing knowledge sharing on social media and its impact on the academic development of Bangladeshi students.

7. Discussion

Bangladesh, an emerging South Asian country, is an ideal choice for data collection and study in the context of this research.

Bangladesh is an emerging economy that has seen dramatic change in recent years. This unprecedented expansion gives researchers a rare opportunity to examine how the spread of knowledge through social media and other technological means has affected the evolution of education. Internet and smartphone usage in Bangladesh has skyrocketed in recent years, with over 100 million users by 2021 [144,145]. Because of the high rate of technological adoption, this area is ideal for research on the impact of the Internet on student-to-student learning and collaboration. Although there is technological proliferation, there still is little use of these factors for study and research. According to the Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics (2022) [146] there are currently 169.8 million people in Bangladesh, and 27.96% of them are between the ages of 15 and 29, making it one of the youngest countries in the world. About 68% of Bangladesh’s population is aged 15–64 years (World Bank, 2022) [147]. Therefore, the demographic segment that this study primarily focused on consisted of students. In addition, the government of Bangladesh has made education a top priority in its development goal, launching programs such as the Smart Bangladesh Vision 2041 [145] to introduce technological learning. Moreover, the collectivist culture of Bangladesh, in which both family and community play an important role in molding individual behavior, makes for an ideal laboratory for investigating the moderating effect of parental involvement on student success. Policy makers and educators can benefit from a better grasp of the cultural dynamics at play when it comes to family and technology. There is a dearth of studies examining the relationship between student-to-student sharing of knowledge on social media and the improvement of education in developing nations such as Bangladesh. This research, if conducted in Bangladesh, will fill a gap in the existing literature and add to our knowledge of this occurrence.

University students in developing countries such as Bangladesh can benefit tremendously from sharing knowledge through social media for academic development, provided that they consider the needs of their families and the limitations of available technology. Students, regardless of where they are physically located, can share and obtain knowledge more efficiently, thanks to the convenience and accessibility offered by social media platforms. However, in some regions of the country, access to the Internet is restricted, and there is a need for more technological infrastructure, both of which can impede the efficiency of the knowledge exchange through social media. In addition, the support of one’s family can also play an essential part in encouraging and facilitating knowledge exchange among university students, specifically for those students who might need access to essential technological resources. Therefore, attempts to encourage knowledge exchange through social media in Bangladesh should concentrate on enhancing technological infrastructure and increasing Internet availability, specifically in remote regions of the country. In addition, educational initiatives should be carried out to encourage the support of university students’ families in their efforts to share their knowledge. By addressing these problems, Bangladesh will be able to enhance the academic development of university students and contribute to creating a more knowledgeable and competent population.

This study aimed to discover whether or not there is a connection between students’ use of social media platforms to share their knowledge and the student’s overall academic growth. The roles of students’ families and the availability and usage of technology were maintained as mediating factors throughout the study. A total of 737 university students participated in the survey and filled out either the online questionnaire or the offline form.

This research contributes to an overall conceptual understanding of the structural relations of social media knowledge sharing and student academic development. This research predicts that knowledge sharing in social media for communication and collaboration significantly and positively influences the student’s academic development. From observation, it was found that the direct and positive influence of communication and collaboration in social media for academic development are significantly related to family and technological support. The findings from the study endorsed the positive relationship of communication and collaboration factors, and there was a mediation of family and technological support between them. This finding is supported by Mahdiuon et al. (2020) [121]. The influence of family and technological support factors on a student’s academic development were positive and significant and strongly supported. Thus, family and technological support play a significant role in a student’s academic performance at the university level. The effect of perceived benefit-related items and academic development of the students in Bangladesh was significant and is supported in the research of Moghavvemi et al. (2018) [148]. Social media has significant value in knowledge sharing, which was also demonstrated by Rahman and Mithun (2021) [17]. Mubassira and Das (2019) [149] studied knowledge sharing through smartphones, which also supported the evidence of academic development in students’ perspectives. In addition, family and technological support mediated the relationship between the perceived benefits of knowledge sharing in social media and academic development was the most positive and significant factor identified in this study. Park and Weng (2020) [150] investigated how country-level economic status and characteristics connected to information and communications technology (ICT) affect student academic attainment. According to the findings, (a) the student’s interest in ICT, perceived ICT competence, and autonomy had positive effects on academic performance; (b) GDP per capita had significant interaction effects on the relationship between ICT-related factors (ICT use for studying at school, for entertainment, and perceived ICT autonomy), and (c) a higher level of student’s perceived ICT autonomy led to better learning outcomes in countries with a lower GDP.

When observing the direct and positive influence of the social value of knowledge sharing in social media and the student’s academic development, the findings supported the conclusion that the social value of knowledge sharing in social media-related factors has a positive relationship with a student’s academic development, which was supported by Ali-Hassan et al. (2015) [119]. However, family and technological support did not mediate the relationship between the social value of sharing knowledge through social media and students’ academic development. The findings provided significant empirical support for the influence of trust on sharing knowledge through social media and students’ academic development, and this was also suggested in the study of Ridings et al. (2002) [151]. This study expanded on Jarvenpaa et al.’s (1998) [152] use of the same trust scales in a virtual team context to apply trust to virtual settings. The team members’ application separated them by time and space, and they did not know each other or have any other relationships. Family and technological support mediated the relationship between the trust of knowledge sharing in social media and academic development. This showed that it had a better value of variance and a high effect on the quality of family and technological issues and academic development. Following the completion of the study, the PLS-SEM test was applied to determine whether or not the mediation effect was statistically significant. According to the findings, there was evidence of mediation.

Theories such as the Technology Acceptance Model (TAM) and the Social Exchange Theory have been employed most frequently in the past in social media to implement knowledge sharing [153,154,155]. This indicates that professionals and researchers have attempted to investigate how sharing knowledge through social media applications might affect users’ intents and actions when using social media.

8. Conclusions

This study offers a valuable summary, making it possible for academics and practitioners to grasp and acquire an overview of the present research and the position of social media in studies on knowledge sharing. The use of social media for knowledge sharing is still a relatively new area of research from the perspective of Bangladesh; hence, the findings of this study can act as a reference for other researchers working in this area. Furthermore, when they are looking to explore the usage of social media in knowledge sharing, it might assist them in finding relevant subjects for their research. Overall, this study adds to the understanding of the connection between social media knowledge sharing and educational development and emphasizes the critical roles that family support and technology infrastructure play. By taking care of these issues, Bangladesh can maximize the potential of social media for academic growth and help its university students progress toward being aware and capable adults.

8.1. Limitations of the Study

The current study has several limitations that should be considered in future research. First, the data were collected from a representative sample of students from public institutions in Bangladesh, so caution should be exercised when generalizing the findings to all higher education institutions in the country. Future studies could benefit from including students from diverse public and private universities. Additionally, the data were only collected from students, and it would be valuable to gather data from a larger sample of educators to validate the research methodology and explore their perspectives on using social media for academic advancement. Finally, most of the data were collected through a Google Form questionnaire, which may introduce response biases and inaccuracies. Therefore, the study has the following specific limitations:

- Sampling bias: The focus on students from Bangladeshi public universities may introduce selection bias, limiting the generalizability of the results to the entire student population in Bangladesh.

- Self-reported information: The reliance on self-reported data may be subject to social desirability bias, where participants provide answers they believe are socially acceptable, potentially affecting the accuracy of the data. Memory bias may also impact the accuracy of participants’ recollections of specific details.

- Limited scope: The study focused primarily on the family and technical factors mediating knowledge sharing on social media for academic growth, overlooking other potential influences such as societal norms, individual characteristics, and university policies.

- Cross-sectional design: Using a cross-sectional design prevents establishing causation between knowledge sharing, family/technical factors, and academic growth. Longitudinal research would provide a better understanding of these relationships over time.

- Although this study provides useful insights into the influence of social media sharing of knowledge on the educational advancement of university students in Bangladesh, it is possible that these findings cannot be generalized to other populations, contexts, or locations. It is possible that different cultures and educational institutions have different characteristics that influence how knowledge is shared and how academics advance.

In order to have a better understanding of how the findings may be generalized to other cultural settings, educational systems, and age groups, further study has to be conducted to investigate the influence of academic growth on the sharing of knowledge through social media. It is also extremely important to take into consideration other possible moderating elements that may impact the link between academic growth and the sharing of knowledge through social media platforms. Some examples of such factors include the role that educators play and the quality of educational materials that can be found on social media platforms. Despite these limitations, the study offers valuable insights into the variables influencing knowledge sharing on social media for academic growth in Bangladesh. Future research should address these limitations to enhance our understanding of this topic further.

8.2. Theoretical Implications

- The study examines how family and technological supports mediate knowledge sharing. This adds theoretical insight into sharing knowledge facilitators.

- It uses Social Exchange Theory and the Technology Acceptance Model. Theoretical integration improves knowledge sharing comprehension.

- The study applies the theoretical model to emerging-country university students. This broadens the sharing of knowledge and technology adoption theoretical frameworks to new groups.

8.3. Practical Implications

- University administrators should encourage family participation and technology assistance to enhance student knowledge transactions. Family engagement with students’ academics may improve knowledge flows.

- Students can utilize social media for sharing knowledge with technology instruction and assistance. Students can learn and improve.

- Instructors and course designers may better use social media for collaborative learning and knowledge sharing by understanding what motivates student knowledge sharing. They can customize social media assignments to students’ knowledge sharing habits.

- The relationship between family support and technology adoption in knowledge sharing might guide social media-based education initiatives in Bangladesh and other developing nations. Interventions that address social and technological enablers should be incorporated.

- Students can learn how family and technology assist knowledge sharing. This can motivate people to use resources and adapt their social media use for learning and cooperation.

In conclusion, the study integrates Social Exchange Theory and Technological Acceptance Models to construct education programs, social media interventions, and student support services. The findings affect university knowledge flow researchers and practitioners.

Author Contributions

The concepts of this research, empirical analysis, and writing were contributed by M.A.H. and X.Z., A.S. and M.I.H. helped with the data analysis. M.M.I. scanned the work. Z.R. assisted in gathering the data. Finally, the conclusions and review of the literature were aided by both authors (M.N.H. and A.K.M.E.A.A.). All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Written informed consent was obtained from each participant before they began the study.

Data Availability Statement

The authors will share the unfiltered raw data that underlie the results of this paper if required.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Filo, K.; Lock, D.; Karg, A. Sport and Social Media Research: A Review. Sport Manag. Rev. 2015, 18, 166–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Z.; Wang, T.; Chen, Y.; Zhang, H. Knowledge Sharing in Online Health Communities: A Social Exchange Theory Perspective. Inf. Manag. 2016, 53, 643–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilgihan, A.; Barreda, A.; Okumus, F.; Nusair, K. Consumer Perception of Knowledge sharing in Travel-Related Online Social Networks. Tour. Manag. 2016, 52, 287–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramayah, T.; Yeap, J.A.L.; Ignatius, J. Assessing Knowledge Sharing Among Academics: A Validation of the Knowledge Sharing Behavior Scale (KSBS). Eval. Rev. 2014, 38, 160–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyd, D.; Ellison, N.B. Social Network Sites: Definition, History, and Scholarship. J. Comput. Mediat. Commun. 2007, 13, 210–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumaraswamy, K.S.N.; Chitale, C.M. Collaborative Knowledge Sharing Strategy to Enhance Organizational Learning. J. Manag. Dev. 2012, 31, 308–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, A.S.; Darji, H.; Mujapara, J.A. A Survey on Role of Intelligent Community and Social Networking to Enhance Learning Process of Students and Professionals. Int. J. Comput. Appl. 2013, 69, 14–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Redmond, F.; Lillis, D. Social Networking Sites: Evaluating and Investigating Their Use in Academic Research. In ICERI2010 Proceedings; IATED: Valencia, Spain, 2010; pp. 5837–5845. [Google Scholar]

- Sabbir Rahman, M.; Highe Khan, A.; Mahabub Alam, M.; Mustamil, N.; Wei Chong, C. A comparative study of knowledge sharing pattern among the undergraduate and postgraduate students of private universities in Bangladesh. Libr. Rev. 2014, 63, 653–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, M.A.; Ikeda, M.; Islam, M.M. Knowledge sharing behaviour influences: A study of Information Science and Library Management faculties in Bangladesh. IFLA J. 2013, 39, 221–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haque, M.; Islam, R. Impact of supply chain collaboration and knowledge sharing on organizational outcomes in pharmaceutical industry of Bangladesh. J. Glob. Oper. Strateg. Sourc. 2018, 11, 301–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubel, M.R.B.; Kee, D.M.H.; Rimi, N.N. The influence of green HRM practices on green service behaviors: The mediating effect of green knowledge sharing. Empl. Relat. Int. J. 2021, 43, 996–1015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jilani, M.M.A.K.; Fan, L.; Islam, M.T.; Uddin, M.A. The influence of knowledge sharing on sustainable performance: A moderated mediation study. Sustainability 2020, 12, 908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, M.S.; Siddike, M.A.K.; Nowrin, S.; Naznin, S. Usage and applications of knowledge management for improving library and information services in Bangladesh. J. Inf. Knowl. Manag. 2015, 14, 1550026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M.S.; Mannan, M.; Hossain, M.A.; Zaman, M.H.; Hassan, H. Tacit knowledge sharing behavior among the academic staff: Trust, self-efficacy, motivation and Big Five personality traits embedded model. Int. J. Educ. Manag. 2018, 32, 761–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M.M.; Mamun, H.A.R.; Al-Amin, M.; Islam, M.T. Measuring the Students’ Perception towards Changed Knowledge Sharing System during the Pandemic: A Case on Public Universities of Bangladesh. Open J. Soc. Sci. 2022, 10, 403–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, S.; Mithun, M.N. Effect of social media use on academic performance among university students in Bangladesh. Asian J. Educ. Soc. Stud. 2021, 20, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiwari, S.P. Emerging Technologies: Factors Influencing Knowledge Sharing. World J. Educ. Res. 2022, 9, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganguly, A.; Talukdar, A.; Chatterjee, D. Evaluating the role of social capital, tacit knowledge sharing, knowledge quality and reciprocity in determining innovation capability of an organization. J. Knowl. Manag. 2019, 23, 1105–1135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.K.; Gupta, S.; Busso, D.; Kamboj, S. Top management knowledge value, knowledge sharing practices, open innovation and organizational performance. J. Bus. Res. 2021, 128, 788–798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, H.; Do, N.K.; Le, P.B. Arousing a positive climate for knowledge sharing through moral lens: The mediating roles of knowledge-centered and collaborative culture. J. Knowl. Manag. 2019, 23, 1586–1604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Hu, Q. Knowledge sharing in supply chain networks: Effects of collaborative innovation activities and capability on innovation performance. Technovation 2020, 94, 102010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nisar, T.M.; Prabhakar, G.; Strakova, L. Social media information benefits, knowledge management and smart organizations. J. Bus. Res. 2019, 94, 264–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, A.; Bahadur, W.; Wang, N.; Luqman, A.; Khan, A.N. Improving team innovation performance: Role of social media and team knowledge management capabilities. Technol. Soc. 2020, 61, 101259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadiq Sohail, M.; Daud, S. Knowledge sharing in higher education institutions: Perspectives from Malaysia. Vine 2009, 39, 125–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalil, O.E.; Shea, T. Knowledge sharing barriers and effectiveness at a higher education institution. Int. J. Knowl. Manag. (IJKM) 2012, 8, 43–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Kurdi, O.F.; El-Haddadeh, R.; Eldabi, T. The role of organisational climate in managing knowledge sharing among academics in higher education. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2020, 50, 217–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Areekkuzhiyil, S. Determinants of Knowledge Sharing Practices among Teachers Working in Higher Education Sector of Kerala. In Knowledge Management in Higher Education Institutions; Manipal University Jaipur: Rajasthan, India, 2022; p. 134. [Google Scholar]

- Hamid, N.A.A. Usage of Social Media Tools in Teaching and Learning and Its Influence on Students Engagement, Knowledge Sharing and Academic Performance. Res. Manag. Technol. Bus. 2020, 1, 278–295. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Y.; Hu, X.; Wei, J.; Marinova, D. The effects of attitudes toward knowledge sharing, perceived social norms and job autonomy on employees’ knowledge sharing intentions. J. Knowl. Manag. 2022. ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Usman, S.H.; Oyefolahan, I.O. Encouraging knowledge sharing using Web 2.0 technologies in higher education: A survey. arXiv 2014, arXiv:1406.7437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Yuan, M.; Xu, Y. An approach to task-oriented knowledge recommendation based on multi-granularity fuzzy linguistic method. Kybernetes 2015, 44, 460–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toro, M.U.; Joshi, M.J. Knowledge sharing in higher education-KMEduSoft. Int. J. Sci. Eng. Res. 2015, 6, 699–702. [Google Scholar]

- Zeraati, H.; Rajabion, L.; Molavi, H.; Navimipour, N.J. A model for examining the effect of knowledge sharing and new IT-based technologies on the success of the supply chain management systems. Kybernetes 2020, 49, 229–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kemp, S. Digital 2023: Bangladesh. Datareportal. 2023. Available online: https://datareportal.com/reports/digital-2023-bangladesh (accessed on 11 June 2023).

- Alavi, M.; Leidner, D.E. Review: Knowledge Management and Knowledge Management Systems: Conceptual Foundations and Research Issues. Mis Q. 2001, 25, 107–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLure Wasko, M.M.; Faraj, S. ‘It is what one does’: Why People Participate and Help Others in Electronic Communities of Practice. J. Strateg. Inf. Syst. 2000, 9, 155–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pathirage, C.P.; Amaratunga, D.; Haigh, R. The Role of Tacit Knowledge in the Construction Industry: Towards a Definition. In Proceedings of the CIB W89 International Conference on Building Education and Research (BEAR), Kandalama, Sri Lanka, 11–15 February 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Nonaka, I.; Takeuchi, H. The Knowledge-Creating Company: How Japanese Companies Create the Dynamics of Innovation. Long Range Plan. 1996, 29, 592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohajan, H.K. Sharing of Tacit Knowledge in Organizations: A Review. Am. J. Comput. Sci. Eng. 2016, 3, 6–19. [Google Scholar]

- Crowley, B. Tacit Knowledge and Quality Assurance: Bridging the Theory-Practice Divide. In Knowledge Management for the Information Professional; American Society for Information Science: Medford, NJ, USA, 2000; pp. 205–220. [Google Scholar]

- Nonaka, I.; Konno, N.; Toyama, R. Emergence of “Ba”. Knowl. Emerg. Soc. Tech. Evol. Dimens. Knowl. Creat. 2001, 1, 13–29. [Google Scholar]

- Magnier-Watanabe, R.; Benton, C.; Senoo, D. A Study of Knowledge Management Enablers Across Countries. Knowl. Manag. Res. Pract. 2011, 9, 17–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekore, J.O. Impact of Key Organizational Factors on Knowledge Transfer Success in Multinational Enterprises. Manag. J. Contemp. Manag. Issues 2014, 19, 3–18. Available online: https://hrcak.srce.hr/file/196719 (accessed on 22 August 2022).

- Park, H.S.; Im, B.C. A Study on the Knowledge Sharing Behavior of Local Public Servants in Korea. 2003. Available online: http://www.kapa21.or.kr/down (accessed on 22 August 2022).

- Lee, C.K.; Al-Hawamdeh, S. Factors Impacting Knowledge Sharing. J. Inf. Knowl. Manag. 2002, 1, 49–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van den Hooff, B.; Elving, W.; Meeuwsen, J.M.; Dumoulin, C. Knowledge Sharing in Knowledge Communities. In Communities and Technologies; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2003; pp. 119–141. [Google Scholar]

- Ishaya, B.; Azamabel, N. Behavioural Impact of Social Media Platforms Among Youths in Yola Metropolis. United Int. J. Res. Technol. 2021, 2, 32–36. [Google Scholar]

- Statista. Number of Social Network Users Worldwide from 2017 to 2025. 2022. Available online: https://www.statista.com/markets/424/topic/540/social-media-user-generated-content/#overview (accessed on 16 January 2022).

- Pekkala, K.; van Zoonen, W. Work-Related Social Media Use: The Mediating Role of Social Media Communication Self-Efficacy. Eur. Manag. J. 2022, 40, 67–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avcı, K.; Çelikden, S.G.; Eren, S.; Aydenizöz, D. Assessment of Medical Students’ Attitudes on Social Media Use in Medicine: A Cross-Sectional Study. BMC Med. Educ. 2015, 15, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Junco, R. Student Class Standing, Facebook Use, and Academic Performance. J. Appl. Dev. Psychol. 2015, 36, 18–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aslam, M.M.H.; Shahzad, K.; Syed, A.R.; Ramesh, A. Social Capital and Knowledge Sharing as Determinants of Academic Performance. J. Behav. Appl. Manag. 2013, 15, 25–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, F.D. Perceived Usefulness, Perceived Ease of Use, and User Acceptance of Information Technology. Mis Q. 1989, 13, 319–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chuttur, M.Y. Overview of the Technology Acceptance Model: Origins, Developments, and Future Directions; Working Papers on Information Systems; 2009; Volume 9. Available online: http://sprouts.aisnet.org/9-37 (accessed on 22 August 2022).

- Fishbein, M.; Ajzen, I. Belief, Attitude, Intention, and Behavior: An Introduction to Theory and Research; Addison-Wesley: Boston, MA, USA, 1975. [Google Scholar]