Abstract

The Russia–Ukraine conflict disrupted a V-shaped economic post-pandemic recovery in Central and West Asia. It affected global supply chains and slowed the region’s growth momentum while adding inflationary pressures. Private businesses were adversely affected by the impact of the conflict and global sanctions against the Russian Federation, with the effects being more pronounced for micro and small firms. The pandemic helped create a base of digitalized firms. As the impact of the conflict began to be felt, how did business digitalization affect the operations of small firms? Would digital finance help fill unmet financing demand from small firms during the difficult time brought by the conflict? This paper assesses the impact of the conflict on digitalized small firms’ operations and discusses the effect of digital finance, and whether it helps small firms survive global economic uncertainty. It uses a linear probability regression based on rapid business surveys conducted in seven Central and West Asian countries—Armenia, Azerbaijan, Georgia, Kazakhstan, the Kyrgyz Republic, Tajikistan, and Uzbekistan. The results show that digitalization has yet to allow small firms to take full advantage of the opportunities it offers for more efficient business operations. Digital finance has yet to be well accepted and used by small businesses, even those already digitalized. Based on the analysis, the paper suggests four policy implications that can help promote business digitalization of small firms and the use of digital finance across the region.

Keywords:

Russia–Ukraine conflict; digitalization; digital financial services; access to finance; SME development; SME policy; Central and West Asia JEL Classification:

D22; G20; L20; L50

1. Introduction

The Russia–Ukraine conflict, which started in late February 2022, interrupted the growth momentum of Central and West Asian economies that had recovered from the coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic. Supported by widespread government assistance programs for individuals and businesses, the Central and West Asian region, which covers Armenia, Azerbaijan, Georgia, Kazakhstan, the Kyrgyz Republic, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, and Uzbekistan, made a V-shape recovery from the pandemic—with their economies growing by 5.7% in 2021, up from the 2% contraction in 2020 and higher than the pre-pandemic growth rate of 4.7% in 2019 [1,2]. However, the region’s growth was hit again—with inflation added—in 2022, affected by the global economic slowdown triggered by the Russia–Ukraine conflict and related sanctions. Growth is currently forecast to drop to 3.9% in 2022. The region’s inflation rate decreased gradually to 7.3% in 2019, but rose to 7.7% in 2020 and 8.9% in 2021 from the impact of the pandemic; it is forecast to further increase to 11.5% in 2022 due to global supply chain disruptions with the Russian Federation—a major trading partner of Central and West Asian economies—along with surging food and commodity prices, and energy costs regionally.

The impact on individual economies varied greatly, presenting either new challenges or new business opportunities. For example, Armenia’s economic growth was projected to increase by 7% in 2022, higher than 2021 (5.7%). The country was able to attract large firms leaving the Russian Federation and expand exports. By contrast, Tajikistan saw economic growth fall from a record 9.2% in 2021 to the 4% forecast in 2022, mainly due to disrupted imports of food and essential goods and diminished remittances from the Russian Federation as many migrant workers returned home.

The conflict thus brought some sharp, structural changes to the business environment across Central and West Asia, though not all in one direction. The impact was magnified for micro, small, and medium-sized enterprises (MSMEs), which are key drivers of economic growth across the region. They accounted for 98.9% of all enterprises, absorbed 46.1% of the workforce, and generated an average 40.7% of a country’s economic output during the period 2010–2021 (Table 1). They contributed an average one-third (32.4%) of exports (by value) from 2015 to 2021—higher than the Southeast Asia average (19.2%). To strengthen the dynamism of MSMEs and create resilient, inclusive growth amid global economic uncertainty, governments need to understand what factors can help this process most effectively to better design MSME policies. Promoting digitalization is one such factor.

Table 1.

MSMEs in Central and West Asia.

Mobility restrictions during the COVID-19 pandemic rapidly accelerated businesses’ digital transformation, including MSMEs. Global research by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development [3] found that up to 70% of small firms had increased their use of digital technology since the pandemic started. Several benefits are considered to arise from digitalization including online product sales (e-commerce) and online business administration. It helps MSMEs better access the information they need, strengthens their networks, offers new domestic and global market opportunities, reduces logistics and administration costs, expands funding opportunities through digital finance platforms such as peer-to-peer lending, and drives more business innovation [3].

An Asian Development Bank (ADB) report [4] found that, while the pandemic and mobility restrictions were an incentive for MSMEs to go digital, those that digitalized were not always successful during the pandemic (The report analyzed MSME survey data tracking the COVID-19 impact on their business operations in Indonesia, the Lao People’s Democratic Republic, the Philippines, and Thailand over a year from March 2020). Two streams of business clusters were created by the pandemic among digitally operated MSMEs—those that increased profits and those that did not. The reasons for MSMEs doing worse were likely associated with marketing, strategic, and management failures—such as products (nonessential goods and services) not aligned with demand during social restrictions, weak business models prior to starting an online business, unfamiliarity with using technology for operations, and poor cost management. The report also found limited use of digital financial services (mobile banking, peer-to-peer lending, and crowdfunding) during the pandemic—even among digitalized MSMEs—due to their unfamiliarity with the technology. Shinozaki [5,6] found a similar trend among digitalized MSMEs in Indonesia, suggesting that more business development services and mentoring support are needed for MSME owners to properly design and manage their online business.

Digital transformation is a post-pandemic policy priority and critical for strengthening competitiveness and helping to build economic resilience against shocks such as the Russia–Ukraine conflict. In Central and West Asia, digitalization remains at an early stage of development, even as digital access has increased in the region (Mobile cellular subscriptions per 100 people averaged 118.3 in 2020 for Central and West Asia [Azerbaijan, Georgia, Kazakhstan, the Kyrgyz Republic, Tajikistan, and Uzbekistan]. An average 66.4% of the region’s people used the internet in 2020 [except for the Kyrgyz Republic in 2019 and Tajikistan in 2017], based on World Bank data [https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/IT.CEL.SETS.P2, accessed on 28 June 2022]). An interoperable national payment system has been created in several countries (These include ArCa [Armenian Card, a unified card payment system launched in 2000] and Idram [an interoperable payment system for commercial banks] in Armenia, instant payment systems using quick response [QR] codes in Azerbaijan and Kazakhstan, Elcard [a national payment switch] in the Kyrgyz Republic, and Humo [a retail payment system] in Uzbekistan. Kazakhstan also plans to introduce a digital currency, the “digital tenge”). Yet, digital financial services such as credit, savings, insurance, and remittance services are not well spread across the region. To use these more widely, national MSME development policies commonly promote MSME competitiveness by adopting new technology (MSME policies in Central and West Asia: Small and Medium Entrepreneurship Development Strategy 2020–2024 in Armenia, SME Roadmap for 2017–2020 in Azerbaijan, SME Development Strategy 2021–2025 in Georgia, Development Concept of SMEs for 2030 in Kazakhstan, National Development Strategy for 2018–2040 in the Kyrgyz Republic, National Development Strategy for 2030 in Tajikistan, and Strategy for Five Priority Areas of Development for 2017–2021 in Uzbekistan. ADB Asia Small and Medium-Sized Enterprise Monitor 2022 Volume I [7]). A national financial inclusion strategy exists in the Kyrgyz Republic, Tajikistan, and Uzbekistan, while a national financial education strategy is being implemented in Azerbaijan, Georgia, and Kazakhstan. The common strategic goal is to diversify financial products, including digital financial services (National Financial Inclusion Strategies in Central and West Asia: Strategy for Improving Financial Inclusion for 2022–2026 in the Kyrgyz Republic, National Strategy for Financial Inclusion for 2022–2026 in Tajikistan, and National Strategy for Increasing Financial Inclusion for 2021–2023 in Uzbekistan. National Financial Education Strategies in Central and West Asia: Strategic Roadmap for Development of Financial Services for 2017–2020 [includes “financial literacy” pillar] in Azerbaijan, National Strategy of Financial Education 2016 in Georgia, and Concept of Improving Financial Literacy for 2020–2024 in Kazakhstan. ADB Asia Small and Medium-Sized Enterprise Monitor 2022 Volume I [7]).

This paper raises fundamental questions about “digitalization” and the use of “digital finance”. How would digitalization work best for a company maintaining and growing its business during crises and global economic uncertainty? How could it strengthen MSME dynamism? Would digital finance help fill unmet financing demand from small firms during the difficult time brought by the conflict? Are there specific conditions or challenges in adapting digitalization and promoting digital finance to sustain business growth?

As the pandemic built a foundation to some extent for digitalizing businesses in the region, this paper examines how digitalized small firms performed 6 months after the conflict, assesses the effect of digital finance for helping small firms survive amid the global economic uncertainty, and discusses the extent to which digitalization and digital finance could handle the challenges brought by the global sanctions against the Russian Federation or create business opportunities. It uses regression models based on data from the seven MSME surveys conducted during the period from July 2022 to August 2022, covering Armenia, Azerbaijan, Georgia, Kazakhstan, the Kyrgyz Republic, Tajikistan, and Uzbekistan. It also discusses policy implications on promoting digital transformation and the use of digital finance for MSMEs and how to deal with related challenges to build more resilient growth.

Section 2 summarizes national policy responses or “anti-crisis actions” to support MSMEs affected by the conflict in the region. Section 3 explains the methodology and data used for analyses. Section 4 discusses the findings from the surveys and econometric analyses in terms of revenues and financial conditions, addressing digitally operated small firms and the use of digital finance, followed by associated policy implications. Section 5 concludes.

2. National Anti-Crisis Actions

The fundamental cause and effect differs between the COVID-19 crisis and the shocks related to the Russia–Ukraine conflict. The epidemic directly attacked people, and each government took quarantine measures and enforced lockdowns to protect people from the pandemic, causing supply chain disruptions and economic and business contractions. Travel bans, border closures, business closures, and mobility restrictions were all attributed to the country’s policy decision; hence, the governments introduced timely economic stimulus packages to reduce the negative effects from quarantine measures, which led to a relatively smooth economic recovery from the pandemic in Central and West Asia.

By contrast, the region’s economic shocks that started in February 2022 arose from an external factor—the Russia–Ukraine conflict. Supply chain disruptions and the slowed growth momentum with inflationary pressures in the region were not triggered by the national policy decision but by sanctions against the Russian Federation. The magnitude of the economic impact is affected by the extent to which the country relies on the Russian economy. Hence, the Russia–Ukraine conflict elicited different reactions from different countries in Central and West Asia. Roughly, they fell into two groups—(i) West Asian countries (Armenia, Azerbaijan, and Georgia) with no comprehensive anti-crisis plan, and (ii) Central Asian countries (Kazakhstan, the Kyrgyz Republic, Tajikistan, and Uzbekistan) that prepared a set of action plans to protect people and businesses from the economic damage caused by the conflict and associated sanctions against the Russian Federation (This section summarizes the key findings from ADB’s Asia Small and Medium-Sized Enterprise Monitor 2022 Volume I [7] and Volume II [8]).

In Armenia, the conflict impact was limited and in fact opened up business opportunities. The Russian Federation is its largest trading partner—with 28% of Armenian exports heading to the Russian Federation in 2021 and 33% of its imports coming from the Russian Federation. Around half (54%) of inward remittances emanated from the Russian Federation in 2021. However, due to tightened restrictions on Armenian migrant workers in the Russian Federation, personal remittances sharply decreased, shifting instead to the United States (US), which accounted for 46% of its inward remittances as of July 2022. Armenian banks were not affected by the global sanctions such as the Russian Federation’s disconnection from SWIFT. Rather, several Russian-based firms and individuals opened bank accounts in Armenia. Moreover, as travel restrictions from the Russian Federation to Europe rose, Armenia benefited from an increase in tourism (41.5% of its tourists came from the Russian Federation in 2021 and this continued to rise in 2022). Armenian exports also benefited as Russian importers looked to increase supply from Armenia. All this contributed to Armenian economic growth in 2022.

Azerbaijan has no comprehensive anti-crisis plan as the economic damage from the conflict was limited. Revenues from its oil industry gained from high oil prices, temporarily covering the impact from lower inward remittances, supply chain disruptions, and higher inflation. However, from a long-term perspective on food supplies, the government has taken specific measures to support farmers and agribusiness, including MSMEs. It is offering cash handouts to farmers, financial assistance to buy fertilizers, concessional leasing of agricultural machinery (50% subsidies), and tax exemptions for agricultural production. Given the high inflation, the government also increased the monthly minimum wage by 20%.

Georgia also has no national anti-crisis plan, while Enterprise Georgia (a policy implementing agency) established an export assistance program for small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs—there is no microenterprises category), given the reduction in foreign trade affected by the conflict. The program has three components: (i) product licensing and certification set to international standards, (ii) product branding, and (iii) expanding its global marketplaces—promoting quality exports to trading partners outside the Russian Federation or Ukraine.

Kazakhstan is being hit primarily by the global sanctions against the Russian Federation, with gross domestic product (GDP) growth forecast to slow from 4.3% in 2021 to 3% in 2022 [1]. The Russian Federation was the source of 42% of the country’s imports. Sanctions immediately created supply disruptions in food and commodities, forcing the country to seek alternative partners for imports. US sanctions on Russian banks—Sberbank, Alfa Bank, and VneshTorgBank (VTB)—in April 2022 affected businesses that use their Kazakhstan branches. Most MSMEs were forced to change bank accounts to other commercial banks. Some Russian Federation- and Belarus-based firms relocated to Kazakhstan, opening bank accounts in Kazakhstan banks; however, this threatens secondary sanctions on Kazakhstan banks. The government acted quickly to respond to the damage and potential damage caused by the sanctions against the Russian Federation by establishing an anti-crisis command center in March 2022. Several assistance measures for domestic firms, including MSMEs and farmers, are being discussed—such as increased subsidies for agriculture-related insurance, concessional leasing of agricultural machinery, and other financial assistance.

In the Kyrgyz Republic, like other neighboring countries, the economy is closely linked to the Russian Federation and Ukraine through trade: In 2021, 24% of Kyrgyz exports and 34% of its imports were with the Russian Federation. With potential trade losses and supply chain disruptions being critical issues, the government quickly responded with an anti-crisis action plan in March 2022. It involved three major pillars: (i) food security and price stability (for example, providing seeds and fertilizers to farmers, diversifying sources for importing crops and fuel, and financial assistance for farmers and agribusinesses); (ii) social protection and safety nets (such as increasing allowances, pensions, and safety net programs); and (iii) MSME employment (such as support for returning migrant workers looking for jobs, deregulating entrepreneurship development, refinancing for agricultural producers and agriculture value chain development, and currency risk sharing for MSME exporters).

Tajikistan relies heavily on the Russian Federation for exports, labor, and remittances. Global sanctions immediately hit the economy, leading to the government’s Anti-Crisis Action Plan in March 2022. The plan covers (i) social protection for the poor and vulnerable (cash transfers), (ii) food security (securing food stock and providing seeds and fertilizers to farmers), and (iii) SMEs hit hard by sanctions on the Russian Federation (returning migrant workers to receive vocational training, and concessional loans offered to SMEs in agriculture, trade, and services).

Uzbekistan also suffered from the conflict and resultant sanctions. The Russian Federation was the main trading partner with Uzbekistan—since 2021, it has been the People’s Republic of China (PRC)—and main destination of Uzbekistan migrant workers, with inward remittances accounting for over 11% of GDP, the highest among Central and West Asian economies. Sanctions hit the economy with supply chain disruptions, high inflation, and reduced inward remittances. In response, from March 2022 to May 2022, the government quickly took countercyclical measures focusing on (i) food security and price stability (importing wheat from Kazakhstan and exempting value-added taxes and customs duties on essential food products), (ii) social protection assistance (cash transfers to the vulnerable population), and (iii) business and job support (financial assistance for entrepreneurs and providing self-employment opportunities for the unemployed and returning migrant workers). Many foreign information technology (IT) specialists have moved to Uzbekistan since early 2022 (on government-issued special three-year IT visas), and many Russian and Belarusian tourists have visited Uzbekistan, benefiting the tourism and IT sectors.

With these two country groups, this study includes an analysis of MSME operations by country group with and without anti-crisis plans.

3. Methodology and Data

The literature analyzing the impact of economic sanctions against the Russian Federation includes Dreger et al. [9] and Sedrakyan [10]. The former used cointegrated vector autoregression (VAR) models to estimate the impact of economic sanctions and oil prices on the Russian Federation’s ruble. A sharp ruble depreciation against the US dollar occurred with the conflict between the Russian Federation and Ukraine in 2014, but the results showed that the ruble depreciation was largely caused by the oil price decline rather than sanctions associated with the conflict, suggesting that the short-term effect of sanctions was likely limited in the Russian economy. Sedrakyan [10] used gravity models of bilateral trade and direct investment to estimate the spillovers of sanctions into third-party countries. The results indicated that the Western and US sanctions against the Russian Federation from 2014 to 2018 largely contracted the Russian Federation’s international trade and investment capacities to 27 transition economies, negatively affecting neighboring countries’ economies. This revealed strong economic ties between the Russian Federation and countries in the former Soviet Union.

From a different angle, this paper focuses on the spillovers of what was brought by the Russia–Ukraine conflict (including sanctions) into businesses in neighboring Central and West Asian countries, addressing digitalized small firms and the use of digital finance, by using a linear probability regression. The study uses data obtained from rapid MSME surveys conducted from 25 July 2022 to 24 August 2022 in seven Central and West Asian countries (Armenia, Azerbaijan, Georgia, Kazakhstan, the Kyrgyz Republic, Tajikistan, and Uzbekistan). The survey questionnaire was delivered online to MSMEs through survey partners, including government authorities, chambers of commerce, and SME associations (The following were survey partners: for Armenia, the European Union-funded Increased Resilience of Syrian Armenians and Host Population [IRIS] program, Impact Hub Armenia Social Innovation Development Foundation [Impact Hub Yerevan], Chamber of Commerce and Industry, European Business Association of Armenia, American Chamber of Commerce in Armenia; for Azerbaijan, the Small and Medium Business Development Agency, American Chamber of Commerce in Azerbaijan, National Confederation of Entrepreneurs’ [Employers’] Organizations; for Georgia, the Small and Medium Enterprises Development Association, Georgian Chamber of Commerce and Industry, Auditing and Consulting Firm “Loialte”; for Kazakhstan, the “DAMU” Entrepreneurship Development Fund, National Chamber of Entrepreneurs; for the Kyrgyz Republic, the Chamber of Commerce and Industry, JIA Business Association, Association of Legal Entities “International Business Council”, Association of Suppliers [Manufacturers And Distributors], Union of Banks of Kyrgyzstan, American Chamber of Commerce in the Kyrgyz Republic, Kyrgyz Union of Industrialists and Entrepreneurs, Association for the Development of the Agro-Industrial Complex, Association of Guarantee Funds and Entrepreneurs; for Tajikistan, the Chamber of Commerce and Industry, National Association of Small and Medium Business, American Chamber of Commerce in Tajikistan, National Association of Business Women of Tajikistan, LLC microcredit deposit organization “FAZOS”; and for Uzbekistan, the Chamber of Commerce and Industry of Uzbekistan, Association of Private Travel Organizations, Association of Textile and Clothing and Knitwear Enterprises, Association of Exporters).

The analysis uses reclassified survey data by firm size (micro and small [MS] firms and medium-sized and large [ML] firms), broad business categories (agriculture, manufacture, and services), and country grouping (West Asian and Central Asian countries). The firm classification refers to the employment threshold as defined nationally, which differs by country but is more unified in West Asia (Table 2). Armenia, Azerbaijan, Kazakhstan, and the Kyrgyz Republic have micro, small, and medium-sized enterprise categories. However, Georgia and Tajikistan define SMEs with no microenterprise category. Uzbekistan has only two categories for micro and small firms. To unify firm size across countries, the analysis focuses on two broad categories—MS and ML. Similarly, industry classifications differ by country. To compensate for this, sector data were reclassified based on the standardized industry classification ADB uses in its Asia SME Monitor database (Table 3). As discussed in Section 2, countries were also reclassified into two groups—(i) West Asian countries (Armenia, Azerbaijan, and Georgia) without comprehensive anti-crisis plans, and (ii) Central Asian countries (Kazakhstan, the Kyrgyz Republic, Tajikistan, and Uzbekistan) that initiated anti-crisis plans.

Table 2.

MSME Definitions Used for Firm Classification, Employment Grouping.

Table 3.

Industry Classification.

The same survey questionnaire was used across countries to collect comparative MSME data (except for country-specific data such as company location). The questionnaire was translated into three languages—English, Russian, and the language of countries surveyed. It had four components: (i) a company profile (a firm’s primary business, location, operating period, employment, wage per employee, annual revenue, engagement of e-commerce, and exposure to global business); (ii) business conditions after the Russia–Ukraine conflict in February 2022 (changes in business environment, sales revenue, employment, wage payments, and fiscal and funding conditions); (iii) business concerns of MSMEs and likely actions should the conflict and associated sanctions continue throughout 2022; and (iv) the policy support measures MSMEs feel they need to maintain their business amid the global economic uncertainty accelerated by the conflict.

3.1. Data Structure

Because of the nature of online surveys, samples were not selected randomly and did not follow the existing national statistics framework; thus, they may have a self-selection problem and nonresponse bias. Due to the need for a snapshot assessing the impact of the Russia–Ukraine conflict on domestic businesses and to find the policies needed, online surveys were the best option to hear what MSMEs had to say even before the full impact was felt.

There were 903 completed responses from firms across the seven countries, but the sample size varied by country—21 firms from Armenia, 83 from Azerbaijan, 144 from Georgia, 112 from Kazakhstan, 392 from the Kyrgyz Republic, 30 from Tajikistan, and 121 from Uzbekistan. This made it difficult to analyze data by country. Thus, the analysis focused on pooling data as regional firm data. There may be different effects among countries, especially between those with and without anti-crisis policy plans. The study incorporates a binary variable into the analysis to see the difference between the two groups: Group A (West Asia: Armenia, Azerbaijan, and Georgia) with 248 samples and Group B (Central Asia: Kazakhstan, the Kyrgyz Republic, Tajikistan, and Uzbekistan) with 655 samples.

As the study uses the pooling data, a weighting adjustment cannot be used to minimize possible bias. To understand the extent of the bias, the distribution of the unweighted survey samples was compared with existing national statistics frameworks (Table 4). The enterprise data aggregated the official number of MSMEs from the national statistics offices for the latest available year (2020 or 2021) and were recalculated as percentage shares by firm size (MS and ML), business sector (agriculture, manufacture, and services), and region (capital city and other regions) (The national MSME definition varies by country [Table 2], but by reclassifying them into two categories [MS and ML], firms with around 50 employees were roughly categorized as MS and those with over 50 employees as ML).

Table 4.

Comparison between Surveys and National Statistics Distribution.

Micro and small firms were underrepresented by 8.4 percentage points in the survey data, while medium-sized and large firms were overrepresented by an equal 8.4 percentage points. There were some differences between MSME surveys and national statistics. By sector, the difference was 26.6% overrepresentation in agriculture, 1.6% overrepresentation in manufacture, and 28.2% underrepresentation in services. The difference in manufacture was limited. By region, the difference was 11.2% overrepresentation in regions outside the capital city. These differences should be considered when interpreting estimate results.

By firm size, 90.7% of respondents (819 firms) owned micro and small firms, with the rest owning medium-sized and large firms. By sector, 47.8% of surveyed firms were in services, followed by 33.6% in agriculture and 18.6% in manufacture. By region, 26% of those surveyed operated in the capital city and 74% in other regions (Capital cities: Yerevan in Armenia, Baku in Azerbaijan, Tbilisi in Georgia, Astana in Kazakhstan, Bishkek in the Kyrgyz Republic, Dushanbe in Tajikistan, and Tashkent in Uzbekistan).

Digitally operated firms—those selling goods and services online (e-commerce)—accounted for 19.4% of the firms surveyed (Table 5). By firm size, they accounted for 18.7% of micro and small firms and 26.2% of medium-sized and large firms; digitalization was likely more advanced in larger firms. By sector, firms in wholesale and retail trade used e-commerce the most (22.9% of digitally operated firms), followed by manufacturing (selling their products online; 16.6%) and agriculture (selling products online; 12.6%).

Table 5.

Profile of Digitally Operated Firms (%).

As for country distribution, Georgia accounted for 35.4% of the digitally operated firms surveyed, followed by Kazakhstan (18.9%), Azerbaijan (16.6%), Uzbekistan (12.6%), the Kyrgyz Republic (9.1%), Tajikistan (4.0%), and Armenia (3.4%). By country group, Group A (West Asia) accounted for 55.4% and Group B (Central Asia) 44.6%.

Mostly young firms operated their business online: 44.6% of digitally operated firms had been operating for 5 years or less, followed by those operating for between 6 and 10 years (25.1%), 11–15 years (16%), 16–30 years (13.1%), and over 30 years (1.1%).

Slightly less than half (44%) of the digitally operated firms surveyed were internationalized firms—those participating in global supply chains or engaged in export and import business. The remaining 56% were focused domestically. By ownership, 33.7% were female-led, with the remaining 66.3% being led by a male.

3.2. Regression Models

The study uses a linear probability model (LPM) to estimate the impact of the Russia–Ukraine conflict on digitally operated firms, addressing MS firms in seven Central and West Asian countries. There are several pros and cons to choosing a binary regression model: LPM or probit and logit regression models. This study chose the LPM because it is more convenient and easier to interpret, computationally less intensive, and reveals similar marginal effects to its nonlinear counterparts [11]. The results of probit models are attached in Appendix B as a robustness test.

The LPM considered seven core factors affecting MSME operations: (i) industry sector; (ii) business location (capital city or outside region); (iii) operating period; (iv) business ownership (gender); (v) global business exposure; (vi) digitalization in operations (online product sales and/or the use of digital finance); and (vii) firm size (employment group). Given the pooling data used for estimates, a binary country group variable (Groups A and B) was added to the model to see the difference in the impact by the level of government intervention. These are the independent variables that explain the impact on two areas of MSME operations: sales revenue and financial condition. These are the binary dependent variables for estimation (Table 6). The model is described by

where is a binary dependent variable denoting the performance of observed firm i at the time of the survey (July 2022–August 2022), or how revenues and financial conditions affected business performance around 6 months after the conflict began in February 2022. is the vector of categories for industry classification (agriculture, manufacture, and the nine categories of services described in Table 3) using “agriculture, forestry, and fisheries” as base. Cnti is the vector of categories for the country where firm i is located, with “Kazakhstan” as base. is a binary variable that takes the value one if firm i operates in the capital city and zero if firm i operates outside of the capital (mostly rural areas). is the vector of categories for years in operation after the establishment of firm i at the time of the survey, with “0–5 years” as base. is a binary variable that takes the value one if the owner of firm i is a “woman” and zero if the owner is a “man”. is a binary variable that takes the value one if firm i is involved in a global supply chain or export/import business and zero otherwise. is a binary variable that takes the value one if firm i is engaged in online selling of goods and services (e-commerce) and zero if not. is a binary variable that takes the value one if firm i uses digital financial services and zero if not. is a binary variable that takes the value one if firm i is a “micro or small enterprise” and zero if the establishment is a “medium-sized or large enterprise”, and ϵ is a residual. Robust standard errors, calculated in the way known as the Huber/White/sandwich estimator, are incorporated into the formula to correct heteroscedasticity of the errors.

Yi = α + β Indi + γ Cnti + δ Regi + ζ Opsi + ψ Womi + η GVCi + ϕ Digi + µ DFSi + τ MSMEi + ϵ

Table 6.

Areas for Impact Analysis.

Y (impact on business performance) comprises two areas with three dimensions that indicate the level of a firm’s resilience to the change in business environment due to the Russia–Ukraine conflict and associated global sanctions (Table 6). The same set of the estimate is performed by country group (A and B) as well to see the difference in impact. Y is also estimated for digitally operated firms in the following model:

where is a binary dependent variable denoting the performance of observed digitally operated firm d at the time of the survey. Independent variables used in Model (2) refer to the same definitions described in Model (1). The estimates show specific impacts on digitally operated firms. This model also takes into account the country group (A and B).

Yd = α + β Indd + γ Cntd + δ Regd + ζ Opsd + ψ Womd + η GVCd + µ DFSi + τ MSMEd + ϵ

4. Findings from the Surveys and Econometric Analyses

The surveys show that the Russia–Ukraine conflict led to several changes in the business environment in Central and West Asia. Operations were continuing in 88.3% of surveyed firms at the time of the survey (July–August 2022), but 7.2% reported limited operations (4.7% less than 50% operational) and 4.5% closed temporarily due to the negative effects of the conflict and associated sanctions. Two groups of firms appeared 6 months after the conflict: those maximizing business opportunities and those adversely affected by the conflict and sanctions. Firms that found the business environment was better than before the conflict comprised a small fraction of the firms surveyed (6%). Many reported that business conditions were unchanged (43%), with those reporting a business environment worse than before comprising a remarkable 29.4% of the firms surveyed. These faced rising production costs (29.4% of firms surveyed) and administrative costs (11.9%) and increased product selling prices to maintain their business (15.0%). While more than 90% of the surveyed firms did not feel a drop in domestic (90.4%) and foreign demand (93.2%), 14.4% reported logistics problems (delayed deliveries to customers), and 7.2% had production and supply chains disrupted, with 5.1% facing contract cancellations. So how could digitally operated firms survive? Were there any differences between digitalized and nondigitalized firms? What key factors helped maintain and grow businesses during the conflict crisis? Does digitalization of business operations and administration—including finance—help firms survive a crisis?

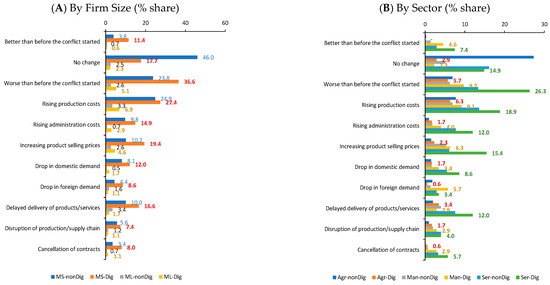

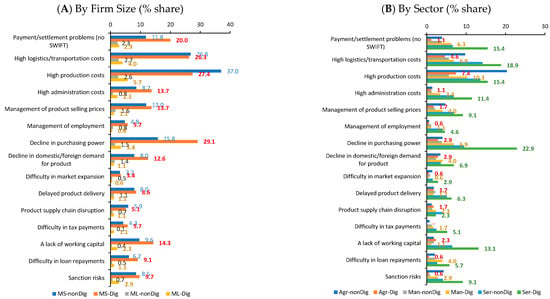

The surveys found that digitally operated firms faced different issues, but the change in business environment was more pronounced in MS firms, negatively affecting 36.6% of digitalized MS firms, 12.8 percentage points higher than nondigitalized MS firms (23.8%) (Figure 1A). This could be because a large share (44.0%) of digitally operated firms are internationalized—those participating in global supply chains or trading in exports and imports, with the Russian Federation being a major trading partner (For nondigitalized firms, the share of internationalized firms was 22.1%). Due to the reliance on imported goods for production, digitally operated MS firms had to deal with large increases in production and operating costs, and responded by sharply raising selling prices—19.4% of digitalized MS firms raised prices, 9.3 percentage points higher than those that were not digitalized (10.2%). The logistics issue (delayed product delivery) was also serious for digitally operated MS firms (16.6%, or 6.5 percentage points higher than nondigitalized MS firms). A fall in domestic and foreign demand was relatively limited for digitally operated MS firms.

Figure 1.

Business Environment after the Russia–Ukraine Conflict. Agri = agriculture, Dig = digitally operated firms, Man = manufacture, ML = medium-sized and large firms, MS = micro and small firms, NonDig = nondigitally operated firms, Ser = services. Notes: Data as percentage share of each group (Dig and NonDig). There were 903 valid samples—21 for Armenia, 83 for Azerbaijan, 144 for Georgia, 112 for Kazakhstan, 392 for the Kyrgyz Republic, 30 for Tajikistan, and 121 for Uzbekistan. There were 819 MS firms and 84 ML firms. There were 303 firms in agriculture, 168 in manufacture, and 432 in services. There were 175 digitally operated firms and 728 nondigitalized firms. Source: Calculations based on pooling data from MSME surveys in Armenia, Azerbaijan, Georgia, Kazakhstan, the Kyrgyz Republic, Tajikistan, and Uzbekistan for 25 July–24 August 2022.

There was a group of digitally operated MS firms that reported a better business environment than before the conflict, accounting for 11.4% of digitalized MS firms, 7.6 percentage points higher than nondigitalized MS firms (3.8%), although they were a small fraction (Figure 1A).

By sector, a relatively higher share of firms reported a better business environment in digitally operated manufacture (4.6%) and service firms (7.4%) than in those not digitalized (Figure 1B). However, a relatively larger share reporting worse conditions was also identified in digitalized service firms (26.3%), 13.0 percentage points higher than in those not digitalized. They faced higher operating costs, which led to higher selling prices. By contrast, digitalized agribusinesses that reported worse business conditions (5.7%) were fewer than those not digitalized (6.9%). Those facing hikes in production costs and price increases were limited. Their reliance on domestic markets and government support may be one of the reasons. For ML firms, the impact on business operations was relatively limited.

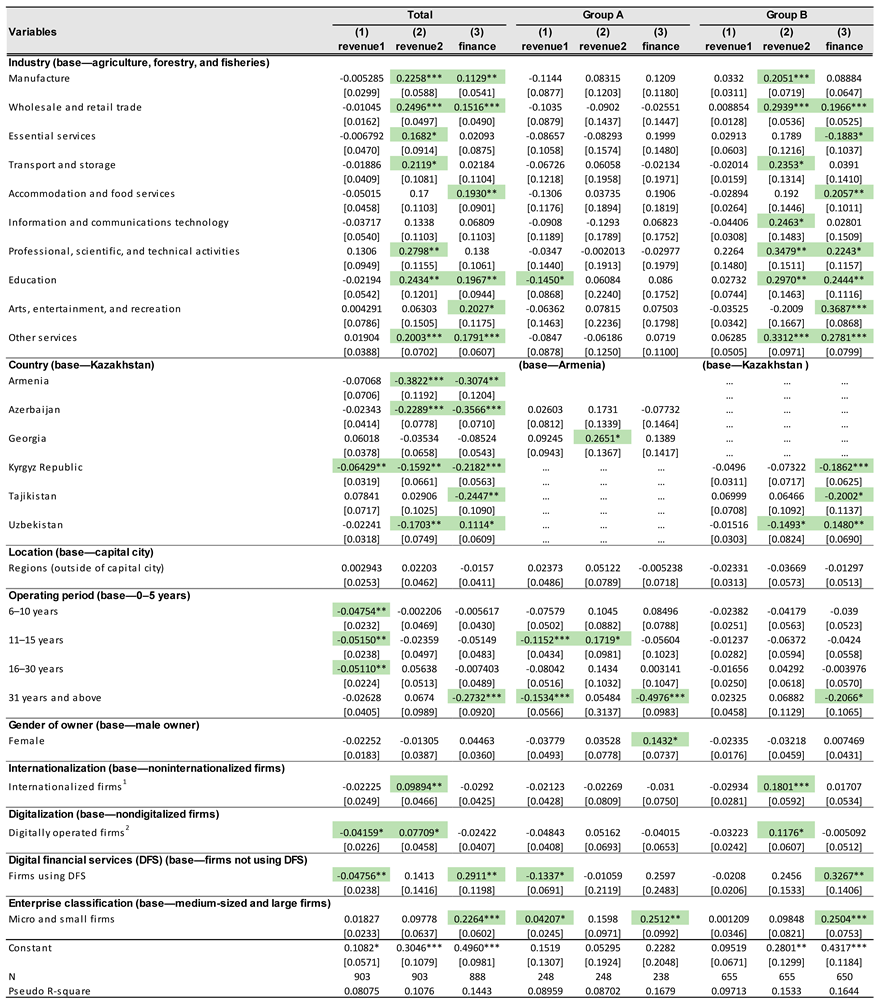

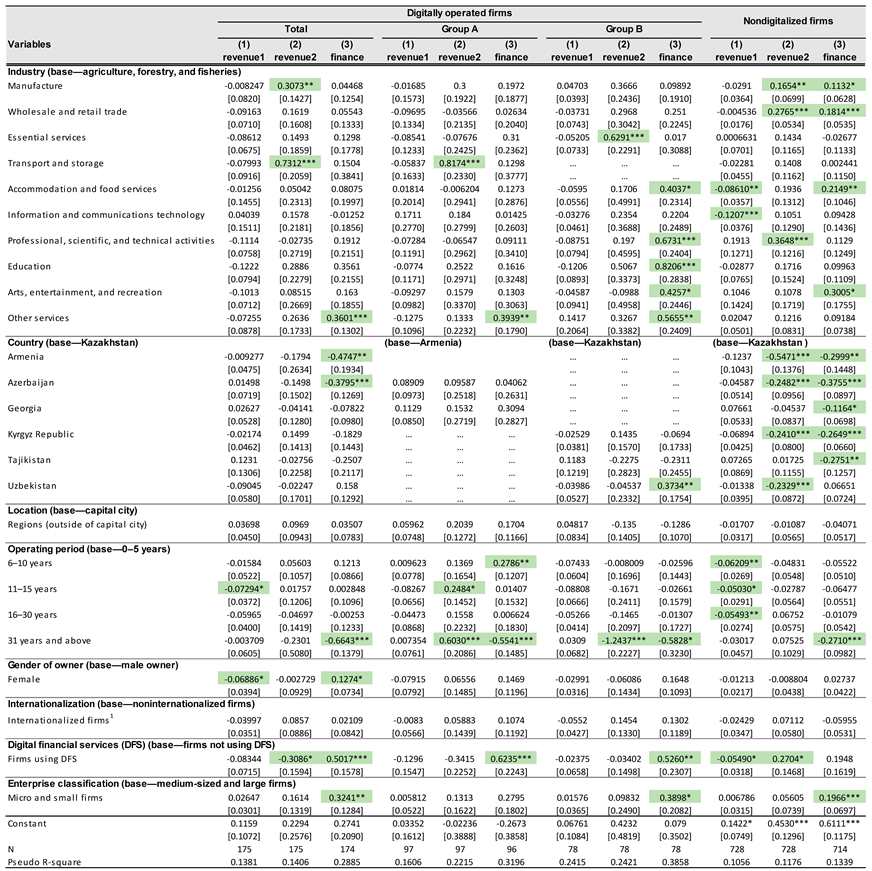

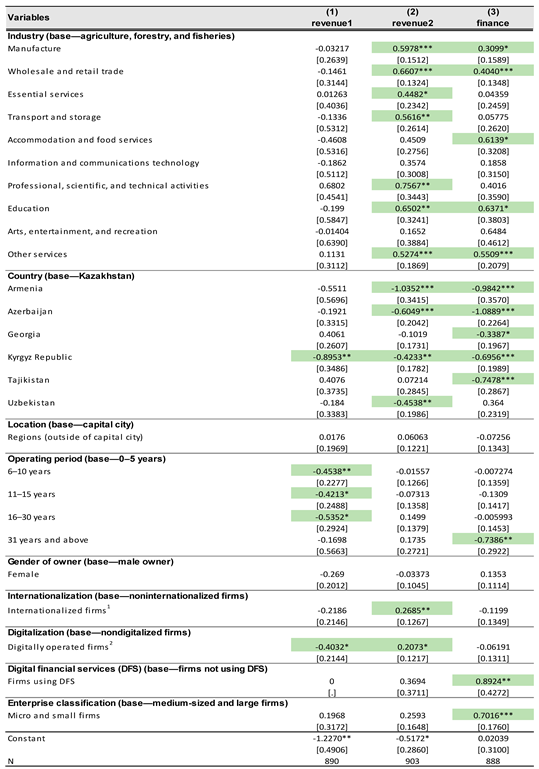

The LPM estimates showed a more detailed analysis on the impact on digitalized firms in terms of sales revenue and finance. Formula (1) was used to estimate the overall impact on surveyed firms where “digitalization” and the use of “digital finance” are included in the factors affecting its operations 6 months after the conflict, which estimates three models (overall effect, and the impacts on firms in country groups A and B) (Appendix A.1). Formula (2) was used to estimate the impact on digitalized firms with three models (overall effect, and the impacts on digitalized firms in country groups A and B) and one model for nondigitalized firms for comparison (Appendix A.2). Each model estimates three dimensions that affect a firm’s resilience to the impact of the conflict and associated sanction measures (The three dimensions are binary dependent variables: (i) revenue1 denotes a dummy variable taking the value one for a firm with no income/revenue at the time of the survey and zero for a firm with income/revenue; (ii) revenue2 denotes a dummy variable taking the value one for a firm with an income/revenue decrease as compared to January 2022 [before the Russia–Ukraine conflict] and zero for a firm with an income/revenue increase or no change; and (iii) finance denotes a dummy variable taking the value one for a firm with no cash/savings at the time of the survey or running out of cash/funds in 3 months and zero for a firm that reported having enough savings, liquid assets, and other contingency finance to maintain business at the time of the survey).

4.1. Impact on Firm Revenue

The LPM regression result (revenue1 and revenue2: see Appendix A.1) found several sectors facing sharp revenue losses at the time of the survey. They were directly or indirectly affected by a slowing Russian economy and the impact of related sanctions, while some were related to chronic national and global problems. The estimates showed that manufacture (manufacturing and construction), wholesale and retail trade, essential services, transport and storage, professional/technical services, education, and other services were more likely to see a revenue decrease than agriculture (the base for comparison) (1%, 5%, or 10% significance level). The essential services include electricity and gas supply, water supply, financial services, and healthcare services—those that are essential for people’s living. Firms in water supply have a chronic problem across Central Asia—water shortages accelerated by climate change will eventually affect agricultural production and hydropower generation [12,13]. Water scarcity may increase the dependence on food and energy imports, and the sanctions on the Russian Federation will increase import costs further with an added currency risk. The LPM estimates on firms with no revenue (due to temporary business closures) were not statistically significant in any business sector.

As compared to the base country Kazakhstan, firms’ revenue losses were less likely in Armenia, Azerbaijan, the Kyrgyz Republic, and Uzbekistan (1% or 5% significance level). Zero-revenue firms were also less likely in the Kyrgyz Republic (5% significance level). Firms operating for more than 6 years were less likely to have no revenue than young firms operating for up to 5 years (5% significance level). In other words, young firms were more likely to be forced to close temporarily, thus receiving no revenue. Internationalized firms saw their revenue drop significantly due to the sanctions on the Russian Federation and currency depreciation compared to purely domestic firms (5% significance level).

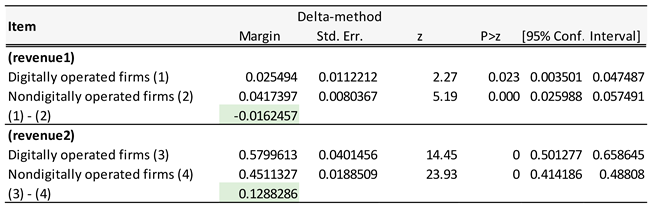

Against these conditions, digitally operated firms were less likely to have zero revenue than those not digitalized (10% significance level). However, those that did had more severe revenue losses as many relied on international trade (10% significance). By country group, digitalized firms in Group B (Central Asia) were more likely to have revenue losses—11.8 percentage points more than nondigitalized firms (10% significance level). Estimates on the revenue of digitalized firms in Group A (West Asia) were not statistically significant. The LPM estimates also did not show statistically significant results for revenue conditions by location (capital city base or other regions), gender of ownership, or firm size. However, MS firms in Group A were more likely to have no revenue than ML firms (10% significance level).

For digitally operated firms (Appendix A.2), revenue losses were more likely in transport and storage (73.1 percentage points higher) and manufacture (30.7 percentage points higher) than in digitalized agribusinesses (the base for comparison) at the 1% or 5% significance level. For nondigitalized firms (Appendix A.2), more sectors (manufacture, wholesale and retail trade, and professional/technical services) likely faced more revenue losses than agriculture (1% or 5% significance level), while accommodation and food services, and information and communications technology (ICT) were less likely to have no revenue than agriculture, suggesting they benefited somewhat from the global sanctions on the Russian Federation—for example, increased tourist and/or IT expert inflows from the Russian Federation and Belarus in some countries. Female-led digitalized firms were less likely to see no income than male-led ones (6.9 percentage points lower at the 10% significance level).

For digitalized firms in Group A, older firms were more likely to see revenue losses than young firms (24.8 percentage points higher in firms that were 11–15 years old at the 10% significance level and 60.3 percentage points higher in firms over 31 years old at the 1% significance level). For those in Group B, firms engaged in essential services were more likely to see revenue losses than digitalized agribusinesses (1% significance level).

Digitalized firms using digital financial services (such as mobile banking, peer-to-peer lending, and crowdfunding) were less likely to see a revenue decrease than those not using digital finance (30.9 percentage points lower at the 10% significance level). For nondigitalized firms, those using digital finance were less likely to face zero revenue than those not using it (5.5 percentage points lower at the 10% significance level) but more likely to decrease revenue than firms not using digital finance (27.0 percentage points higher at the 10% significance level); they likely failed to use digitally raised money to stop revenue losses.

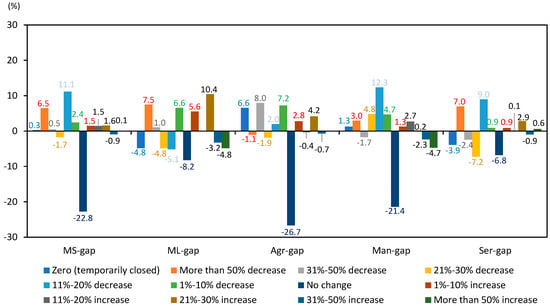

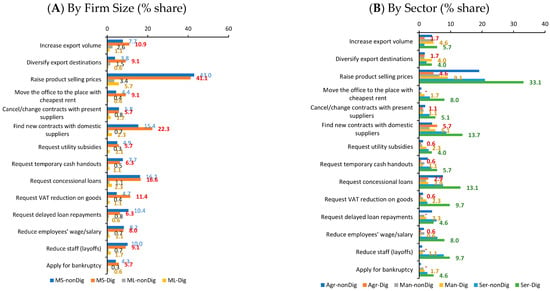

The LPM estimates on revenue by firm size were not statistically significant in digitalized firms, but a descriptive analysis provides a more detailed picture (Figure 2). The response ratio gap in revenue between digitally operated firms and nondigitally operated firms by firm size and business sector is calculated as the share of digitally operated firms minus that of nondigitalized firms to their respective populations, where a positive value indicates a higher percentage share in digitalized firms, and a negative value indicates a lower percentage share than in nondigitalized firms.

Figure 2.

Revenue—Digitally Operated Enterprises. Agri = agriculture, Man = manufacture, ML = medium-sized and large firms, MS = micro and small firms, Ser = services. Notes: The gap is calculated as the share of digitally operated firms minus that of nondigitally operated firms. There were 903 valid samples—21 for Armenia, 83 for Azerbaijan, 144 for Georgia, 112 for Kazakhstan, 392 for the Kyrgyz Republic, 30 for Tajikistan, and 121 for Uzbekistan. There were 819 MS firms and 84 ML firms. There were 303 firms in agriculture, 168 in manufacture, and 432 in services. There were 175 digitally operated firms and 728 nondigitalized firms. Source: Calculations based on pooling data from MSME surveys in Armenia, Azerbaijan, Georgia, Kazakhstan, the Kyrgyz Republic, Tajikistan, and Uzbekistan for 25 July–24 August 2022.

Digitally operated MS firms that reported “no change” were likely a smaller fraction than those not digitalized. Rather, the two streams of profitable and unprofitable firms appear among digitalized MS firms after the conflict (11.1 percentage points higher for firms with an 11%–20% drop in income and 4.5 higher for those with up to a 30% income increase) (Figure 2). Digitalized ML firms followed the same pattern but had more mixed results in profitability. By sector, two types of business groups were more evident in digitally operated agriculture and manufacture firms selling products online. In Central Asia, irrigated agriculture is costly due to the scarcity of water, limited access to imported fertilizers, and high energy costs (due to the sanctions on the Russian Federation), contributing to higher selling prices. Some firms supplying the domestic market were profitable, while others that did not manage costs well became unprofitable. Many digitally operated firms in manufacturing exported goods, mainly to the Russian Federation as a major trading partner. Those that successfully diversified trade destinations outside the Russian Federation gained. For digitally operated services, cost management was pivotal in terms of profitability.

4.2. Financial Conditions

4.2.1. Fiscal Condition

The Russia–Ukraine conflict and global sanctions against the Russian Federation damaged many firms’ revenues and led many to cut staff and wages to cover surging production and operating costs [14]. Some firms in Central and West Asia, however, took advantage of new opportunities in financial services and tourism, but they remained a small fraction. Digitalized firms were less likely to lose revenue or close temporarily. However, those involved in international trade affected by sanctions lost more income and cut more staff than nondigitalized firms. Most firms surveyed struggled to survive 6 months into the conflict and tried several cost management techniques, as many started facing insufficient finance to operate.

The LPM estimates (finance) found MSMEs faced a difficult financial (“fiscal”) situation—either out of cash and savings or running out in 3 months from the time of the survey—in manufacture (11.3 percentage points higher than agriculture [base]), wholesale and retail trade (15.2 higher), accommodation and food services (19.3 higher), education (19.7 higher), entertainment services (20.3 higher), and other services (17.9 higher) at the 1%, 5%, or 10% significance level (Appendix A.1). By country, firms in Uzbekistan were more likely to face financial problems than those in Kazakhstan, the Kyrgyz Republic, Tajikistan, Armenia, and Azerbaijan (1%, 5%, or 10% significance level; the figure for Georgia was not statistically significant). Young firms (up to 5 years) were more likely to face working capital shortages than older firms.

Female-led digitalized firms were more likely to have no cash and savings or a shortage of finance in 3 months, 12.7 percentage points higher than male-led digitalized firms (10% significance level) (Appendix A.2). Digitally operated firms using digital financial services followed, 50.2 percentage points higher than digitalized firms not using digital finance (1% significance level). The lack of finance was more serious in digitalized MS firms, 32.4 percentage points higher than digitalized ML firms (5% significance level). Digitalized firms facing financial problems tended to use digital finance to strengthen their working capital.

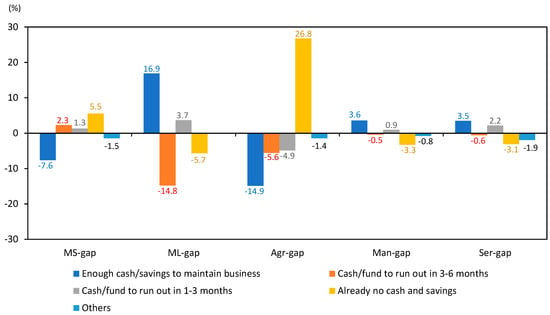

According to gap analysis, the share of digitalized MS firms with no cash and savings was 5.5 percentage points higher than that of nondigitalized MS firms, while the share of digitalized ML firms with sufficient cash and savings was 16.9 percentage points higher than that of those not digitalized—but those running out of funds within 3 months had a 3.7% higher share than those not digitalized (Figure 3). By sector, digitalized agribusinesses had more serious financial problems—the share of those without cash or savings was 26.8 percentage points higher than that of nondigitalized agribusinesses. For digitalized firms in manufacture and services, the share of those reporting enough cash and savings was around 3.5 percentage points higher than that of those not yet digitalized.

Figure 3.

Financial Conditions—Digitally Operated Enterprises. Agri = agriculture, Man = manufacture, ML = medium-sized and large firms, MS = micro and small firms, Ser = services. Notes: The gap is calculated as the share of digitally operated firms minus that of nondigitally operated firms. There were 903 valid samples—21 for Armenia, 83 for Azerbaijan, 144 for Georgia, 112 for Kazakhstan, 392 for the Kyrgyz Republic, 30 for Tajikistan, and 121 for Uzbekistan. There were 819 MS firms and 84 ML firms. There were 303 firms in agriculture, 168 in manufacture, and 432 in services. There were 175 digitally operated firms and 728 nondigitalized firms. Source: Calculations based on pooling data from MSME surveys in Armenia, Azerbaijan, Georgia, Kazakhstan, the Kyrgyz Republic, Tajikistan, and Uzbekistan for 25 July–24 August 2022.

4.2.2. Funding

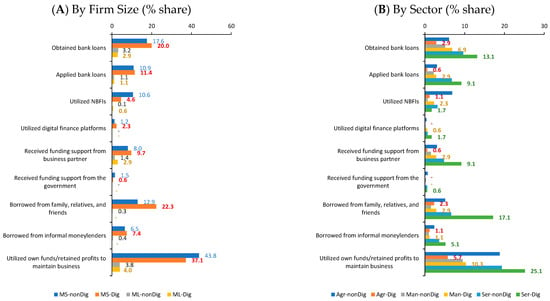

The Russia–Ukraine conflict happened just as economies were recovering from the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic in Central and West Asia. Nationally, financial assistance programs for individuals and businesses continued into 2022—including concessional lending programs (subsidized loans) and special credit guarantees. To minimize the impact of the conflict and related sanctions, governments—beginning March 2022—offered additional assistance such as cash handouts to farmers and agribusinesses including MSMEs (Azerbaijan), subsidies for agriculture (Kazakhstan), concessional loans (refinancing facility) for agricultural producers and currency risk-sharing for MSME exporters (the Kyrgyz Republic), concessional loans to SMEs hit hardest by sanctions on the Russian Federation (Tajikistan), and financial assistance for entrepreneurs and those self-employed (Uzbekistan). Nevertheless, the firms surveyed faced financial problems, especially MS firms, even those already digitalized. There were many sectors facing more serious financial shortages than agriculture (base), but digitalized agribusinesses had severe financial issues. What are the major funding sources for MSMEs in Central and West Asia? How could firms raise working capital to survive during the crisis? How did digitalized firms fare (Figure 4)?

Figure 4.

Funding after the Russia–Ukraine Conflict. Agri = agriculture, Dig = digitally operated firms, Man = manufacture, ML = medium-sized and large firms, MS = micro and small firms, NonDig = nondigitally operated firms, Ser = services. Notes: Data as percentage share of each group (Dig and NonDig). There were 903 valid samples—21 for Armenia, 83 for Azerbaijan, 144 for Georgia, 112 for Kazakhstan, 392 for the Kyrgyz Republic, 30 for Tajikistan, and 121 for Uzbekistan. There were 819 MS firms and 84 ML firms. There were 303 firms in agriculture, 168 in manufacture, and 432 in services. There were 175 digitally operated firms and 728 nondigitalized firms. Source: Calculations based on pooling data from MSME surveys in Armenia, Azerbaijan, Georgia, Kazakhstan, the Kyrgyz Republic, Tajikistan, and Uzbekistan for 25 July–24 August 2022.

Overall, most firms continued to rely on their own funds, retained profits, or money borrowed from family, relatives, and friends. The latter was more evident among digitalized MS firms (22.3%) than nondigitalized MS firms (12.9%) (Figure 4A). Backed by government assistance programs (subsidized loans and credit guarantees), the share of firms that received bank loans was relatively high (20% for digitalized MS firms and 17.6% for nondigitalized MS firms). The share using digital finance platforms was higher among digitalized firms (2.3%) than those not digitalized (1.2%), but it was a very small share. By sector, the pattern was similar (Figure 4B).

The use of digital technology has been increasing across Central and West Asia. National payment systems now exist in most countries, but digital financial services such as credit, savings, insurance, and remittances have yet to be utilized widely in the region, as the survey findings showed.

4.3. Policy Implications

4.3.1. Concerns of Digitalized Small Firms

The surveys asked firms what the major concerns and obstacles they faced were, including those digitally operated and those nondigitalized (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Concerns and Obstacles Faced by MSMEs. Agri = agriculture, Dig = digitally operated firms, Man = manufacture, ML = medium-sized and large firms, MS = micro and small firms, NonDig = nondigitally operated firms, Ser = services. Notes: Data as percentage share of each group (Dig and NonDig). There were 903 valid samples—21 for Armenia, 83 for Azerbaijan, 144 for Georgia, 112 for Kazakhstan, 392 for the Kyrgyz Republic, 30 for Tajikistan, and 121 for Uzbekistan. There were 819 MS firms and 84 ML firms. There were 303 firms in agriculture, 168 in manufacture, and 432 in services. There were 175 digitally operated firms and 728 nondigitalized firms. Source: Calculations based on pooling data from MSME surveys in Armenia, Azerbaijan, Georgia, Kazakhstan, the Kyrgyz Republic, Tajikistan, and Uzbekistan for 25 July–24 August 2022.

For digitalized MS firms, the top concern was a decline in purchasing power (29.1%), which was 13.3 percentage points higher than for nondigitalized MS firms (Figure 5A). Respondents felt that a prolonged conflict and sanctions would further increase inflation and the downside risks facing the economy, more seriously reducing household income and living standards, which in turn raises the risk of a continuing sharp drop in sales revenue.

This was followed by operational concerns: 27.4% worried about high production costs, such as higher prices for primary products; 26.3% high logistics and transportation costs; 20% payment and settlement problems due to the ban on SWIFT transfers from the Russian Federation; 14.3% a lack of working capital; and 13.7% high administration costs and managing product price increases. Payment problems and high administrative costs were cited more by digitalized MS firms than those not digitalized (8.2 and 5.1 percentage points higher, respectively).

A decline in domestic and foreign demand for their products and “sanction risks” also concerned MS firms, especially those that were digitalized (12.6%, or 4.6 percentage points higher than nondigitalized MS firms over the decline in demand, and 9.7%, slightly higher [+1.2] than nondigitalized MS firms, for potential sanction risks). Firms were worried that the increased number of Russian-based firms and individuals moving into their economies and the new bank accounts opened would increase the risk of local banks being added to global sanction lists.

Other concerns included difficulty in loan repayments (9.1%), delayed product delivery (8.6%), employment management such as ensuring employees are paid (5.7%), tax payments (5.7%), supply chain disruptions (5.1%), and barriers to market expansion (3.4%). There was little difference between digitally operated service firms and digitalized MS firms in general (Figure 5B).

4.3.2. Actions Considered by Digitalized Small Firms

In response to their worries, the firms surveyed considered taking counteractions (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Actions Considered by MSMEs. Agri = agriculture, Dig = digitally operated firms, Man = manufacture, ML = medium-sized and large firms, MS = micro and small firms, MSME = micro, small, and medium-sized enterprise; NonDig = nondigitally operated firms, Ser = services. Notes: Data as percentage share of each group (Dig and NonDig). There were 903 valid samples—21 for Armenia, 83 for Azerbaijan, 144 for Georgia, 112 for Kazakhstan, 392 for the Kyrgyz Republic, 30 for Tajikistan, and 121 for Uzbekistan. There were 819 MS firms and 84 ML firms. There were 303 firms in agriculture, 168 in manufacture, and 432 in services. There were 175 digitally operated firms and 728 nondigitalized firms. Source: Calculations based on pooling data from MSME surveys in Armenia, Azerbaijan, Georgia, Kazakhstan, the Kyrgyz Republic, Tajikistan, and Uzbekistan for 25 July–24 August 2022.

For digitally operated MS firms, the top actions considered were related to “marketing” matters: increase in selling prices (41.1% of digitalized MS firms); finding new contracts with domestic suppliers (22.3%, or 6.9 percentage points higher than nondigitalized MS firms); increase in export volumes (10.9%, 3.2 percentage points higher); diversifying export destinations (9.1%, 5.3 percentage points higher); and cancellation or renegotiation of contracts with current suppliers (5.7%) (Figure 6A). This was followed by adjustments to internal control and management systems: finding lower-cost office space (9.1%, 4.7 percentage points higher); layoffs (cutting staff) (9.1%); reducing employee wages/salaries (8%); and applying for bankruptcy (5.7%). Firms also wanted the support from government and financial authorities: (in order of preference) concessional loans (16.6%); reduced value-added tax (VAT) on goods (11.4%, 6.8 percentage points higher); temporary cash handouts (6.3%); delayed loan repayments (6.3%); and utility subsidies (5.7%).

The top five options considered by digitalized firms in services were: (i) increasing product selling prices (33.1%, 12.3 percentage points higher than nondigitalized services firms); (ii) finding new contracts with domestic suppliers (13.7%, 5.1 percentage points higher); (iii) requesting concessional loans (13.1%, 5.6 percentage points higher); (iv) requesting reduced VAT on goods (9.7%, 7.1 percentage points higher); and (v) laying off staff (9.7%, 1.9 percentage points higher) (Figure 6B).

4.3.3. Policies Desired by Digitalized Small Firms

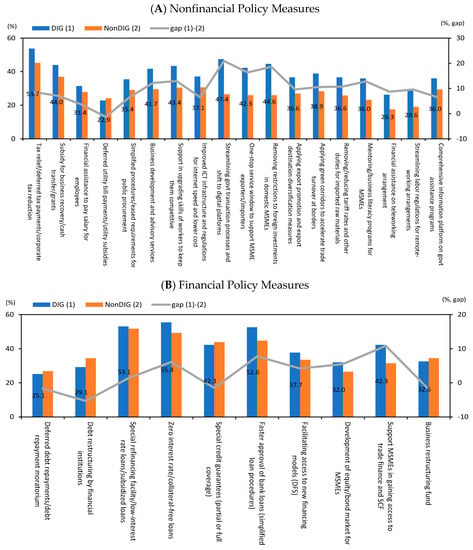

There were nonfinancial and financial policy measures that digitally operated firms were hoping for at the time of the survey, with data based on “strongly needed” answers out of the five choices (Figure 7) (The five were “strongly needed”, “somewhat needed”, “neutral”, “somewhat not needed”, and “least needed”).

Figure 7.

Policy Measures Desired by MSMEs. DFS = digital financial services; DIG = digitally operated firm; ICT = information and communications technology; MSME = micro, small, and medium-sized enterprise; NonDIG = nondigitalized firm; SCF = supply chain finance. Notes: Based on answers “strongly needed”. The gap is calculated as the share of digitally operated firms minus that of nondigitally operated firms. There were 903 valid samples—21 for Armenia, 83 for Azerbaijan, 144 for Georgia, 112 for Kazakhstan, 392 for the Kyrgyz Republic, 30 for Tajikistan, and 121 for Uzbekistan. There were 819 MS firms and 84 ML firms. There were 303 firms in agriculture, 168 in manufacture, and 432 in services. There were 175 digitally operated firms and 728 nondigitalized firms. Source: Calculations based on pooling data from MSME surveys in Armenia, Azerbaijan, Georgia, Kazakhstan, the Kyrgyz Republic, Tajikistan, and Uzbekistan for 25 July–24 August 2022.

For nonfinancial policies (Figure 7A), the top measure desired was “tax relief”, including deferred tax payments and reduced corporate income tax (53.7% of digitally operated firms, 8.5 percentage points higher than nondigitalized firms). This was followed by “streamlining government transaction processes and shift to digital platforms” (47.4%, 20.9 percentage points higher). Furthermore, 37.1% were looking for “improved ICT infrastructure and regulations for internet speed and lower cost” (6.5 percentage points higher than for those not digitalized)—digital infrastructure development recently picked up under national financial inclusion strategies in several Central and West Asian countries.

Other nonfinancial policy measures digitalized firms wanted (in order of preference) were removing restrictions on foreign investments in domestic MSMEs (44.6%, 18.6 percentage points higher); subsidies for business recovery/cash transfer/grants (44%, 7.1 percentage points higher); support to upgrade worker skills (43.4%, 12.9 percentage points higher); one-stop service windows for MSME exporters/importers (42.3%, 16.3 percentage points higher); business development and advisory services (41.7%, 12.2 percentage points higher); using green corridors to accelerate trade at borders (38.9%, 10.6 percentage points higher); measures to promote exports and diversify destinations (36.6%, 9.7 percentage points higher); removing/reducing tariff rates and other duties for imported raw materials (36.6%, 10.8 percentage points higher); mentoring/business literacy programs for MSMEs (36%, 12.8 percentage points higher); creating a comprehensive information platform on government assistance programs (36%, 6.6 percentage points higher); simplified procedures and requirements for public procurement (35.4%, 6.5 percentage points higher); financial assistance to pay salaries (31.4%, 3.6 percentage points higher); streamlining labor regulations for remote-working arrangements (28.6%, 9.6 percentage points higher); and financial assistance for teleworking arrangements (26.3%, 8.7 percentage points higher).

For financial policy measures (Figure 7B), the top measure desired was zero interest and collateral-free loans (55.4%, 6.1 percentage points higher), followed by special refinancing facilities or low-interest and subsidized loans (53.1%, 1.4 percentage points higher); faster bank loan approvals (simplified loan procedures) (52.6%, 7.8 percentage points higher); support for MSMEs in gaining access to trade and supply chain finance (42.3%, 10.8 percentage points higher); special credit guarantees (42.3%, 1.5 percentage points lower); access to new financing models (digital financial services) (37.7%, 4.2 percentage points higher); creating a business restructuring fund (32.6%, 1.9 percentage points lower); developing MSME equity/bond markets (32%, 5.5 percentage points higher); debt restructuring (29.1%, 5.3 percentage points lower); and deferred debt repayments or a debt repayment moratorium (25.1%, 1.7 percentage points lower). Digitally operated firms wanted quick, low-cost finance for working capital during crises.

4.3.4. Lessons from the Survey Findings and Regression Models

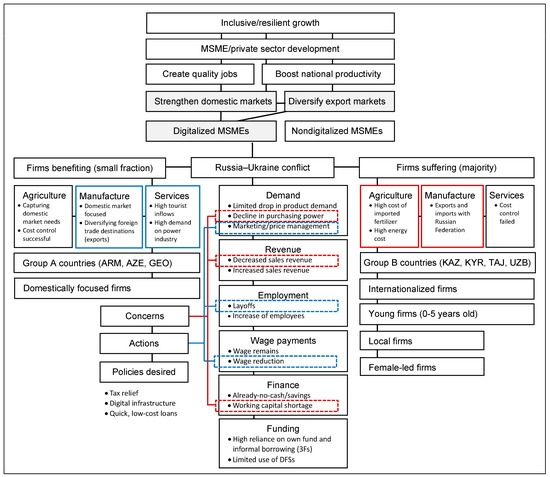

Following the Russia–Ukraine conflict, the region’s economic growth was forecast to slow down with higher inflation in 2022. Sanctions against the Russian Federation and currency depreciation disrupted global supply chains, limited crop and essential goods imports, reduced demand for exports, and delayed (or suspended) foreign trade payments. This adversely affected private sector business operations, especially for smaller firms, due to surging production and operating costs.

The LPM showed that many business sectors—including manufacture, wholesale and retail trade, essential services, transport and storage, professional/technical services, education, and other services—faced sharp revenue losses after the conflict started in February 2022. Exporters and importers saw large drops in revenue with the Russian Federation being a major trading partner. Younger firms (aged up to 5 years) also faced sharp income losses.

Digitally operated firms could avoid having no revenue or temporary closures. However, as many trade internationally, they had to deal with higher income losses than those that were not digitalized.

Two groups were identified 6 months after the conflict: MSMEs grasping business opportunities (profitable firms) and those adversely affected by the conflict and global sanctions (unprofitable firms) (Figure 8). For digitalized MS firms selling online, those in agriculture and manufacturing were hit harder.

Figure 8.

Impact of the Russia–Ukraine Conflict on Digitalized MSMEs—Evidence from Surveys and Linear Probability Models. ARM = Armenia; AZE = Azerbaijan; DFS = digital financial service; 3Fs = friends, family, fools; GEO = Georgia; KAZ = Kazakhstan; KYR = Kyrgyz Republic; MSME = micro, small, and medium-sized enterprise; TAJ = Tajikistan; UZB = Uzbekistan. Note: Analysis on “Employment” and “Wage payments” mentioned above is based on Shinozaki (2023) [14]. Source: Author.

In Central Asia, agricultural production has faced several issues—such as water scarcity for irrigated fields (cotton, for example), difficulty in obtaining imported fertilizers, and high energy and transportation costs (due to sanctions)—which contributed to raising product prices. Those capturing domestic market needs and/or receiving government assistance maintained profitability, while those that could not manage costs became unprofitable.

Many digitalized manufacture firms export to the Russian Federation as a major trading partner. Those focusing on domestic markets or diversifying exports away from the Russian Federation gained.

Among nondigitalized firms, more sectors than in digitalized firms (manufacture, wholesale and retail trade, and professional/technical services) suffered from revenue losses. The impact was less severe in some sectors such as accommodation and food services, and ICT. They likely benefited from the sanctions on the Russian Federation—there were more tourist and/or IT expert inflows from the Russian Federation and Belarus in some countries.

By country group, digitalized firms in Group B (Central Asia) were likely to see more revenue losses than those that were not digitalized.

After 6 months, many firms lacked sufficient funds to continue operations. Firms that had no cash and savings or would run out in 3 months were in manufacture, wholesale and retail trade, accommodation and food services, education, entertainment services, and other services—more likely in digitalized MS and younger firms. There were just a few digitalized firms in manufacture and services that had enough cash and savings.

Government emergency assistance programs established during the pandemic continued in most countries. Furthermore, the conflict-related anti-crisis plans were in Group B countries—cash transfers and concessional loans for agribusinesses and MSMEs. New programs were implemented beginning March 2022, but financial conditions remained problematic for those surveyed, especially MS firms, and for those that had been digitalized.

As for funding sources, most firms still relied on their own funds, retained profits, or money borrowed from family, relatives, and friends. However, government financial assistance (subsidized loans and credit guarantees) increased the number of firms surveyed receiving bank loans. Digitally operated firms used more digital finance platforms than those not digitalized, but it was still just a small share. Digitalized firms experiencing fiscal problems tended to use digital finance for working capital.

The surveyed firms generally felt that drops in domestic and foreign demand would be limited, but their top concern, especially for digitalized MS firms, was a decline in purchasing power. A long conflict (and sanctions) will increase the risk of higher inflation and further economic damage, lowering household purchasing power, and increasing the risk that MSMEs will have reduced sales revenue over the longer term.

This caused firms to worry more about operational matters—high production and operating costs, a lack of working capital, and managing product selling prices. This was more pronounced among digitalized MS firms.

Another concern was a “sanction risk”, due to increasing inflows of Russian-based firms and individuals and the new bank accounts opened in local banks, increasing the risk that they would be added to those facing global sanctions.

Digitally operated MS firms felt they needed to act on marketing (top priority)—managing product pricing, selecting new domestic suppliers, and diversifying export destinations. For internal controls, layoffs and reducing wages were among priority actions contemplated.

The surveys also found that digitally operated firms wanted nonfinancial policies such as tax relief, including deferred tax payments and reduced corporate income tax (top choice), followed by government assistance to digitalize. They also wanted improved ICT infrastructure and regulations on internet speed and lower subscription costs so they can swiftly enter the e-commerce industry. Furthermore, digitally operated firms wanted the government to support their access to quick, low-cost finance for working capital.

Overall, digitalization has yet to allow small firms to take full advantage of the opportunities it offers for more efficient business operations. The pandemic helped create a base of digitalized firms; business digitalization happened as an option to survive against the mobility restrictions. Many digitally operated firms were indulged in unprofitable business due to their weak strategies before starting an online business and unfamiliarity with using technology for operations. This was more pronounced in Central Asian countries hit hard by the conflict impact, where anti-crisis plans have yet to be effective for supporting MSME operations at the time of the survey.

Digital finance helped digitalized small firms to some extent to survive the conflict impact, filling their insufficient working capital and partly minimizing their revenue losses. It also somewhat helped nondigitalized small firms to operate but was unlikely to stop their revenue losses. Fundamentally, however, digital finance has yet to be well accepted and used by small businesses, even those already digitalized.

To ensure sustainable business digitalization and promote the use of digital finance for MSMEs, the government assistance to digitalize should be elaborated, strengthened, and disseminated further.

4.3.5. Policies to Help Digitalize Business

Several policy implications from the study findings can help promote business digitalization and the use of digital finance for MSMEs in Central and West Asia:

- Strengthen domestic commodity markets through business cluster development:

Digitalizing operations alone will not necessarily help export-oriented businesses as their operating costs increased markedly due to the global sanctions on the Russian Federation. The LPM found that internationalized firms faced sharp revenue losses, particularly in digitalized smaller firms. By contrast, firms that focused on domestic markets and/or successfully managed rising costs could even grow during the conflict crisis. Firms need a feasible business model before taking their business online, closely monitoring the current business environment and adapting their business strategy accordingly. High operating costs came from excessive reliance on imported inputs for production and high energy/transportation costs. Targeting more domestic clients and better using domestic inputs for production can help when external costs are too high or rising. Improving and strengthening domestic commodity markets by developing business clusters can better localize inputs and link production segments, where business digitalization can materialize its benefits effectively.

- Diversify exports using a national branding strategy with digital trade facilitation:

With many MSMEs, especially digitalized firms, involved in global supply chains or international trade in the region, a firm’s export strategy should address marketing and cost management. It is critical for firms to strengthen their own product branding—and use more domestic inputs—to diversify export markets globally. The government should develop a national branding strategy to accelerate the process. A well-digitalized trade facilitation system (cross-border paperless trade) would incentivize more MSMEs and startups to develop global business with low cost.

- Assist the MSME digital transformation by promoting the use of technologies in operations, linked to entrepreneurship development:

Many MSMEs are in low-technology industries or distributive trade. Their business operations and administration are typically based on cash. They are unfamiliar with technologies needed to start and manage an online business. Digitalization offers several benefits to startups and entrepreneurs and catalyzes business innovation. Literacy programs and advisory services should be well designed and offered to growth-oriented MSMEs—including young and women entrepreneurs. In particular, given the increased importance of environmental, social, and governance (ESG) for MSME business, the assistance should help guide the transfer and adoption of new technology, as well as promote sustainable investment in research and development (R&D) for green entrepreneurships through digital platforms.

- Diversify alternative financing options by developing sustainable digital finance platforms, along with strengthening its ecosystem and financial education for MSMEs:

The LPM indicated that working capital shortages were a serious problem for digitally operated smaller firms to survive under the conflict impact. Government financial assistance gradually improved MSME access to bank credit, but the region’s financial systems still rely on subsidies; market-based financing such as capital markets and digital financial services remain underdeveloped. In Central and West Asia, firms do not apply digital finance solutions sufficiently, in part due to their lack of basic knowledge on digital finance. Equity crowdfunding has developed in some developing Asian countries such as Thailand—but not in Central and West Asia. More diversified financing options are needed to fill unmet financing needs in an era of global uncertainty, developing digital finance ecosystem (rulemaking), products, infrastructure, and financial literacy and education programs. These should be well designed and implemented following a national financial inclusion strategy.

5. Conclusions

The Russia–Ukraine conflict started during the economic recovery from the COVID-19 pandemic in Central and West Asia. It disrupted global supply chains, slowed growth momentum, and added to inflation. Private businesses were adversely affected by the impact of the conflict and global sanctions, which was more pronounced for smaller firms.

With the pandemic helping to build a base for digitalizing businesses, this paper has discussed how business digitalization and the use of digital finance affected MSME operations during the first 6 months of the conflict and related sanctions. The LPM regressions and survey findings conducted for the seven Central and West Asian countries indicated that digitalization remains at an early stage for MSMEs operating in the region. Digitally operated MS firms fell into two groups: those maximizing business opportunities and those that suffered from the Russia–Ukraine conflict and global sanctions. A well-designed strategy before starting an online business—including a cost management plan—is key to helping businesses survive and grow sustainably. Digital finance has yet to be well accepted by MSMEs, even if digitalized, due mainly to their unfamiliarity with the technology.

Based on the analysis, this paper provides four policy implications to promote MSME business digitalization in the region: (i) developing domestic commodity markets through business clustering; (ii) expanding and diversifying exports using a national branding strategy with digital trade; (iii) linking the digital transformation with entrepreneurship development; and (iv) creating alternative financing options—more pronounced in sustainable digital finance platforms—by strengthening its ecosystem and financial education for MSMEs.