Feminine vs. Masculine: Expectations of Leadership Styles in Hotels during the COVID-19 Pandemic

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Rationale for Research, Literature Review, and Hypotheses Development

2.1. Leadership and Leadership Styles

2.2. Feminine, Masculine, and Androgynous Leadership Styles

2.3. Styles and the Effectiveness of Leadership in Crisis—Rationale for Research

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Introductory Remarks

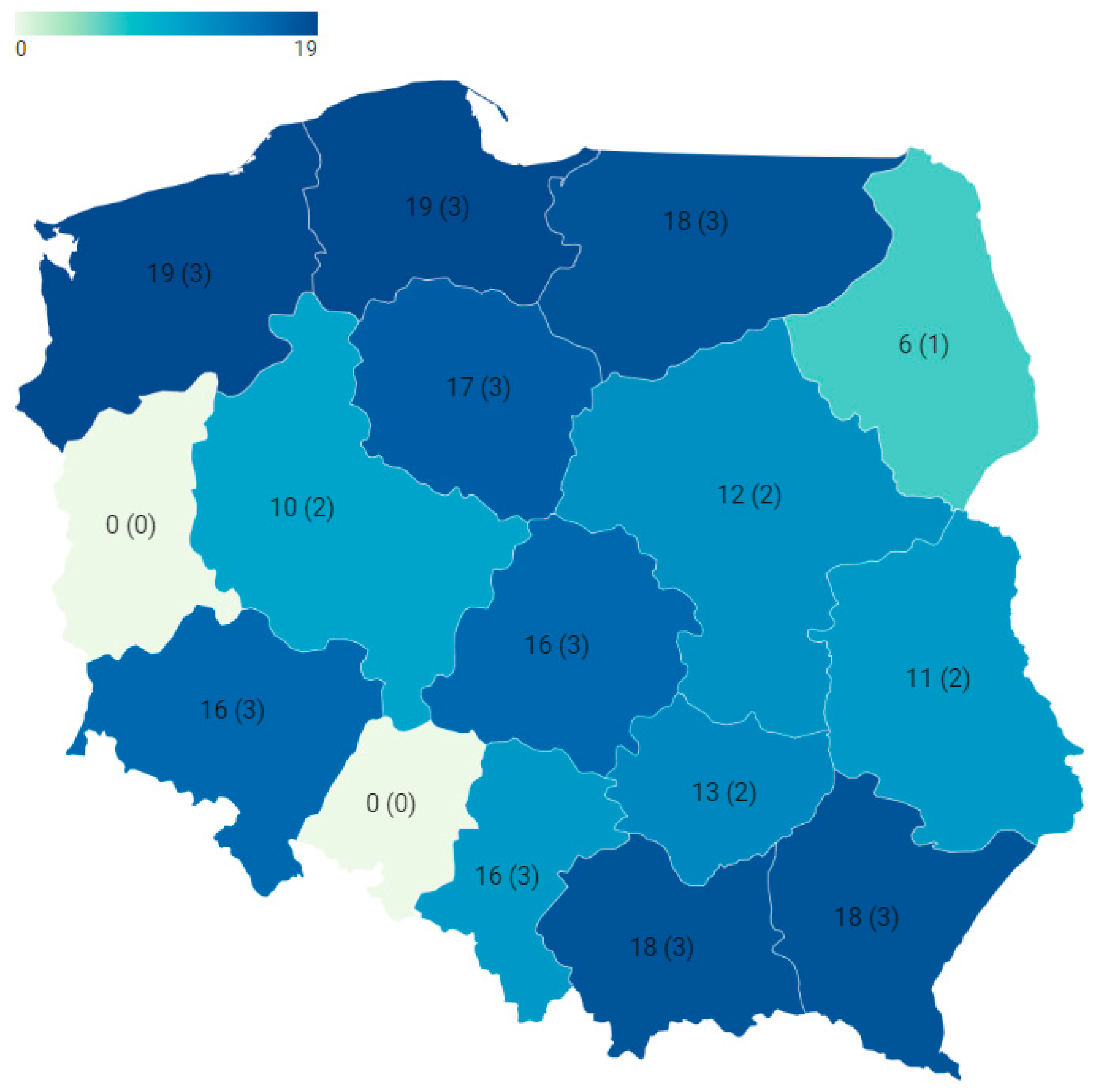

3.2. Sample and Data Collection

- Before the collection of formal data, a pilot focus group with 15 participants was conducted to confirm the validity of the selection of crisis leadership criteria in the hotel industry.

- The main research (in-person semi-structured interviews) was focused on the characteristics and effectiveness of distributed leadership practices, as well as the factors that had exerted an impact on them.

- In the last part of the study, staff fluctuation in the surveyed hotels was analyzed to determine the impact of leadership style on employee retention.

- Empathy and care (EC);

- Transparency and communication (TC);

- Adaptability (AD);

- Resilience and courage (RC);

- Decisiveness and risk-taking (DR);

- Inclusivity, collaboration, and empowerment (ICE).

4. Results

4.1. The Perception of Crisis Leadership Styles

“We felt annoyed when we didn’t know what was going on, and the leader didn’t want to say anything. We didn’t know if we would have enough money for a long time, whether we had enough money to cover the costs of our salaries or even electricity bills. The leader treated us paternalistically, like children with nothing to worry about. And we were terribly worried”.(Respondent 134)

“The leader kept telling us to do our job and leave the worries to him. At first, it seemed ok, but after a few days we were nervous. Nobody knew anything; the leader was lost too, but he still pretended to know what to do. And after three weeks, he suddenly announced that we would be made redundant”.(Respondent 12)

- Problems with daily shopping—a large part of the surveyed hotels are located in small towns, where problems with provisioning were much more significant than in larger cities (a problem reported by 114 respondents);

- The problem of access to electronic devices that could enable remote learning, especially in families with two or more children and only one computer at the disposal of the whole family (153 respondents);

- The problem of a place to work remotely in large families, where not every family member has their own room (78 respondents);

- The problem with the care of children who at that time were homeschooled and thus remained unattended (to) if both parents worked (167 respondents);

- The inability to provide adequate substantive support to children who found remote learning difficult (183 respondents);

- Fear for the health of loved ones and the need to care for the sick (86 respondents);

- Hindered access to doctors in the first period of the pandemic (74 respondents);

- Lack of hygiene products and masks in the first period of the pandemic (122 respondents).

“I had no idea (of) how to deal with shopping—both stores in our town were closed, and we didn’t have a car. The leader proposed a daily shopping list—we sent it by e-mail until 9.00 a.m. and at 11.00 a.m., a delivery truck left for shopping”.(Respondent 111)

“(…) and this constant problem with medical masks—throughout the first days, we constantly wore scarves on our faces. When the leader finally got medical masks for the hotel, he provided for our entire families”.(Respondent 78)

“I couldn’t help the children with their homework—I have three of them, and jumping from math to history and then suddenly to physics was beyond my strength. The manager asked us to report who could help the children and in what areas. Then we took turns doing shifts, for which the children applied: “mathematics emergency” and “language emergency”. I had no idea we had brains like that before”.(Respondent 15)

“I have a small apartment—2 rooms, and there are four of us. My husband worked from home; the children had remote lessons. Total confusion. We asked the boss if we could use the hotel rooms as office spaces when the hotel was closed. The idea turned out to be a great solution. We conversed 12 rooms into study rooms. Then we came up with the idea that the remaining 21 rooms could be rented as co-working spaces for external guests. They were all occupied until the end of the pandemic. Sometimes up to 80 people used such an office per one day. We only took decontamination breaks. The hotel kitchen was also satisfied—businessmen working in our rooms ordered meals for themselves, and after a few days they started ordering takeaways”.(Respondent 105)

“Every morning, there was a briefing, and the leader asked if everyone was healthy, what was going on at home, and told them to report any problems. We had a big whiteboard, like in crime movies; we wrote down problems and ideas for solutions, and then we looked in our heads for friends or contacts to help. Three people were “the crisis team”—we reported solutions to them, and they were looking for people and other resources for this”.(Respondent 204)

“I was amazed by how much time the leader spent listening to our problems: children, sick mother, no painkillers. I wouldn’t be surprised if he was a social person daily, but I’ve been working here for five years, and maybe I’ve talked to him twice”.(Respondent 40)

“To me, the most important thing was honest communication […]. I wanted to know where I stood, even if I had to find out we were finally closing the hotel. This uncertainty was tiring me out, and I would prefer to know how to prepare […]”(Respondent 51)

“People were scared and uncertain, and the boss didn’t tell us anything”.(Respondent 64)

“We knew that the boss did not know more than us, but he fed us news every morning and told us what was discussed at IGHP meetings (The Chamber of Commerce of the Polish Hotel Industry). If he (had) planned any meetings (e.g., in a tourist organization), he said what topics they would discuss and what their plans were. It gave the impression that we had something under control and that there was nothing to fear. I’d rather be at work than at home. At home, everyone constantly talked about Covid statistics, however, at work we just tried to act”.(Respondent 113)

“The more confusion there was in the media, the more we wanted clear information from the leader […]”.(Respondent 160)

“I was tired of these side-by-side discussions—I wanted the boss to call us together in one place and tell us what and how […]”.(Respondent 118)

“[…] We were waiting for a meeting so that people would hear what’s next, e-mails with a cursory question about our condition caused rather an irritation. […]”.(Respondent 70)

“When I mentioned that disinfectant was needed, the boss got angry that I was spreading panic and that this virus was a political invention. When he saw me wearing a mask in the hallway, he always commented on it. Many people did not wear masks so as not to hear it”.(Respondent 44)

“(…) at work, there was still tension and anger. There was no work, and the boss shouted that we were not doing anything. We started replanting the flowers, and he got angry that we were wasting our time. And there wasn’t a single guest”.(Respondent 61)

“I couldn’t cope—all day in an empty hotel, without guests, and I was nervous about what was happening at home with the children during this time. We sat with our arms folded. The boss said that if we wanted, we could take a holiday, but he announced that he would not give us leave during the school holidays”.(Respondent 99)

“The boss got angry that I had refused to make reservations, but at that time only guests on a business trip were allowed. The boss said he’d take control and I was not to bother with politics”.(Respondent 156)

“Almost all of them [other employees] went to commerce or simply sat at home without work. The hotel was supposedly in debt, and we didn’t get paid, no one knew what the next decisions would be. Only me and two waitresses remained out of the old staff (23 people)”.(Respondent 103)

“(…) I did not know why the leader had exposed us to such a threat. If the doctors did not want to go home so as not to put their loved ones at risk, we did not want to risk it either. After all, you had to enter such a room every day, disinfect it, prepare meals for the doctors, and talk to them. I didn’t understand how you could endanger your employees like that”.(Respondent 7)

“I was glad that the boss had applied for permission to open a hotel for a medic. We were terrified of this empty hotel, and now we could work normally and still feel that we were doing something that helped people. It was sad to see those exhausted nurses. They were unable to make tea in the evening”.(Respondent 66)

“We were glad when the boss agreed to build a tennis court, volleyball court and picnic area. Some of the property should have been used for sports facilities long ago, but there was still no time. We had more than enough, and everyone was working in the garden. It was even cool while sitting in an empty hotel kind of scared us”.(Respondent 32)

“I couldn’t understand how you could force us to clean the garden in this weather. It was March, there was still snow, full of rotten leaves, we were afraid of colds, and the boss said we had to do something to keep from getting bored. We mainly employ women: receptionists, maids and waitresses. Why should we do garden work? Every year it was done by an external company”.(Respondent 123)

“In my opinion, the leader must be self-assured and decisive because if the crew sees that he does not know what he is doing and where he is going, how will he deal with confused employees […] Everyone prefers a leader who simply takes responsibility”.(Respondent 73)

“We desperately needed someone who could instill in us faith that everything would be fine […]”.(Respondent 158)

4.2. Crisis Leadership and Staff Retention

5. Discussion

6. Future Research

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Cerqua, A.; Di Stefano, R. When did coronavirus arrive in Europe? Stat. Methods Appl. 2022, 31, 181–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- UNWTO. COVID-19 Related Travel Restriction. A Global Review for Tourism. Sixth Report as of 30 July 2020. 2020. Available online: https://www.icao.int/EURNAT/EUR%20and%20NAT%20Documents/COVID%2019%20Updates-%20CAPSCA%20EUR/08%20August%202020%20COVID19%20Updates/COVID-19%202020-08-01-Updates/Travel%20Restrictions%20Sixth%20Report%2028%20July%202020.pdf (accessed on 10 June 2023).

- UNWTO. COVID-19 and Tourism. 2021. Available online: https://www.unwto.org/covid-19-and-tourism-2020 (accessed on 30 March 2023).

- UNWTO. World Tourism Barometer. 2023, Volume 21. Available online: https://webunwto.s3.eu-west-1.amazonaws.com/s3fs-public/2023-01/UNWTO_Barom23_01_January_EXCERPT.pdf?VersionId=_2bbK5GIwk5KrBGJZt5iNPAGnrWoH8NB (accessed on 30 March 2023).

- Lai, I.K.W.; Wong, J.W.C. Comparing crisis management practices in the hotel industry between initial and pandemic stages of COVID-19. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2020, 32, 3135–3156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canhoto, A.I.; Wei, L. Stakeholders of the world, unite!: Hospitality in the time of COVID-19. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2021, 95, 102922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Act on Special Measures Related to the Prevention, Counteracting and Combating of COVID-19, Other Infectious Diseases and Emergencies Caused by Them. Journal of Laws of the Republic of Poland of 2nd March 2020, Item 374. Available online: https://isap.sejm.gov.pl/isap.nsf/DocDetails.xsp?id=WDU20200000374 (accessed on 10 June 2023).

- Statistics Poland, Occupancy of Tourist Accommodation Establishments in Poland in November and December 2020. News Releases Published on 4 February 2021. Available online: https://stat.gov.pl/en/topics/culture-tourism-sport/tourism/occupancy-of-tourist-accommodation-establishments-in-poland-in-november-and-december-2020,5,26.html (accessed on 10 June 2023).

- Dirani, K.M.; Abadi, M.; Alizadeh, A.; Barhate, B.; Garza, R.C.; Gunasekara, N.; Ibrahim, G.; Majzun, Z. Leadership competencies and the essential role of human resource development in times of crisis: A response to COVID-19 pandemic. Hum. Resour. Dev. Int. 2020, 23, 380–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serwis Rzeczpospolitej Polskiej. Koronawirus: Informacje i Zalecenia. 2023. Available online: https://www.gov.pl/web/koronawirus (accessed on 10 June 2023).

- Croes, R.; Semrad, K.; Rivera, M. The State of the Hospitality Industry 2021 Employment Report: COVID-19 Labor Force Legacy. Dick Pope Sr. Institute Sr. for Tourism Studies Working Paper 27 October 2021. Available online: https://hospitality.ucf.edu/wp-content/uploads/sites/2/2021/10/state-of-the-hospitality-10282021web-compressed.pdf (accessed on 10 June 2023).

- Chung, H.; Quan, W.; Koo, B.; Ariza-Montes, A.; Vega-Muñoz, A.; Giorgi, G.; Han, H. A threat of customer incivility and job stress to hotel employee retention: Do supervisor and co-worker supports reduce turnover rates? Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 6616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shin, Y.; Hur, W.M.; Park, K.; Hwang, H. How ‘managers’ job crafting reduces turnover intention: The mediating roles of role ambiguity and emotional exhaustion. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public 2020, 17, 3972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demirović, B.D.; Terzić, A.; Petrović, M.D.; Radovanović, M.; Tretiakova, T.N.; Hadoud, A. Will we have the same employees in hospitality after all? The impact of COVID-19 on employees’ work attitudes and turnover intentions. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2021, 94, 102754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fink, S.L.; Beak, J.; Taddeo, K. Organizational Crisis and Change. J. Appl. Behav. Sci. 1971, 7, 15–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- James, E.H.; Wooten, L.P. Leadership as (Un) usual: How to display competence in times of crisis. Organ. Dyn. 2005, 34, 141–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, G.R.; George, J.M. Essentials of Managing Organisational Behaviour; Prentice-Ha: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Stogdill, R.M. Personal Factors Associated with Leadership: A Survey of the Literature. J. Psychol. 1948, 25, 35–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mrówka, R. Przywództwo w Organizacjach; Wolters Kluwers: Warszawa, Poland, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Yukl, G. Leadership in Organization, 7th ed.; Pearson: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Fiaz, M.; Su, Q.; Ikram, A.; Saqib, A. Leadership styles and employees’ motivation: Perspective from an emerging economy. J. Dev. Areas 2017, 51, 143–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demirtas, O.; Karaca, M. A Handbook of Leadership Styles; Cambridge Scholars Publishing: Cambridge, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Rawat, P.; Lyndon, S. Effect of paternalistic leadership style on subordinate’s trust: An Indian study. J. Indian Bus. Res. 2016, 8, 264–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dike, E.E.; Madubueze, M.H.C. Democratic Leadership Style and Organizational Performance: An Appraisal. Int. J. Dev. Strateg. Humanit. Manag. Soc. Sci. 2019, 9, 129–138. [Google Scholar]

- Hinkin, T.R.; Schriesheim, C.A. An examination of “nonleadership”: From laissez-faire leadership to leader reward omission and punishment omission. J. Appl. Psychol. 2008, 93, 1234–1248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baskarada, S.; Watson, J.; Cromarty, J. Balancing transactional and transformational leadership. Int. J. Organ. Anal. 2017, 25, 506–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bass, B.M.; Riggio, R.E. Transformational Leadership; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc.: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Caillier, J.G. Can changes in transformational-oriented and transactional-oriented leadership impact turnover over time? Int. J. Public Adm. 2018, 41, 935–945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tannenbaum, R.; Schmidt, W.H. How o Choose a Leadership Pattern. Harv. Bus. Rev. 1973, 51, 162–180. [Google Scholar]

- Blake-Beard, S.; Shapiro, M.; Ingols, C. Feminine? Masculine? Androgynous leadership as a necessity in COVID-19. Gend. Manag. 2020, 35, 607–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koenig, A.M.; Eagly, A.H.; Mitchell, A.A.; Ristikari, T. Are leader stereotypes masculine? A meta-analysis of three research paradigms. Psychol. Bull. 2011, 137, 616–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eagly, A.H.; Johnson, B.T. Gender and leadership style: A meta-analysis. Psychol. Bull. 1990, 108, 233–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartol, K.M. The sex structure of organizations: A search for possible causes. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1978, 3, 805–815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dobbins, G.H.; Platz, S.J. Sex differences in leadership: How real are they? Acad. Manag. Rev. 1986, 11, 118–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adler, N.J.; Osland, J.S. Women Leading Globally: What We Know, Thought We Knew, and Need to Know about Leadership in the 21st Century. Adv. Glob. Leadersh. 2016, 9, 15–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eagly, A.H.; Carli, L.L. The female leadership advantage: An evaluation of the evidence. Leadersh. Q. 2003, 14, 807–834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiedler, F. The contingency model and the dynamics of the leadership process. Adv. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 1978, 11, 59–112. [Google Scholar]

- Bem, S.L. The measurement of psychological androgyny. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 1974, 42, 155–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blausten, P. Can authentic leadership survive the downturn? Bus. Strategy Rev. 2009, 20, 84–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peus, C.; Wesche, J.S.; Streicher, B.; Braun, S.; Frey, D. Authentic leadership: An empirical test of its antecedents, consequences, and mediating mechanisms. J. Bus. Ethics 2012, 107, 331–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerzema, J.; D’Antonio, M. The Athena Doctrine: How Women (and the Men Who Think like Them) Will Rule the Future; Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Stentz, J.E.; Plano Clark, V.I.; Matkin, G.S. Applying mixed methods to leadership research: A review of current practices. Leadersh. Q. 2012, 23, 1173–1183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, B.; Turner, L.A. Data collection strategies in mixed methods research. In Handbook of Mixed Methods in Social & Behavioral Research; Teddlie, C., Tashakkori, A., Eds.; SAGE Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2003; pp. 297–319. [Google Scholar]

- Waller, V.; Farquharson, K.; Dempsey, D. Qualitative Social Research: Contemporary Methods for the Digital Age; SAGE: London, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Mumford, M.D. A hale farewell: The state of leadership research. Leadersh. Q. 2011, 22, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bass, B.M. Bass & Stogdill’s Handbook of Leadership: Theory, Research, and Managerial Applications, 3rd ed.; The Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Bass, B.M. Transformational Leadership: Industrial, Military, and Educational Impact; Erlbaum: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Bass, B.M. ‘Bass’ Handbook of Leadership: Theory, Research and Managerial Applications, 4th ed.; Free Press: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Creswell, J.W.; Clark, V.L.P. Designing and Conducting Mixed Methods Research; SAGE Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Veal, A.J. Research Methods for Leisure and Tourism: A Practical Guide, 4th ed.; Pearson Education: London, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Culha, A. Inclusive Leadership Practices in Schools, A Mixed Methods Study. MSKU J. Educ. 2013, 10, 70–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willis, J. Foundations of Qualitative Research: Interpretive and Critical Approaches; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Glaser, B.G.; Strauss, A.L. The Discovery of Grounded Theory: Strategies for Qualitative Research; Aldine Publishing Company: Chicago, IL, USA, 1967. [Google Scholar]

- Strauss, A.; Corbin, J. Basics of Qualitative Research: Grounded Theory Procedures and Techniques, 2nd ed.; Sage Publication: London, UK, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, J.A.; Eatough, V. Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis. In Research Methods in Psychology; Breakwell, G., Smith, J.A., Wright, D., Eds.; Sage: London, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Harding, J. Qualitative Data Analysis from Start to Finish; SAGE: London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Edmunds, H. The Focus Group Research Handbook; NTC Business Books: Lincolnwood, IL, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Fontana, A.; Frey, J.H. The interview: From neutral stance to political involvement. In The Sage Handbook of Qualitative Research, 3rd ed.; Denzin, N.K., Lincoln, Y.S., Eds.; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2005; pp. 695–727. [Google Scholar]

- Morris, A. A Practical Introduction to In-Depth Interviewing; SAGE: London, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Walsham, G. Doing Interpretive Research. Eur. J. Inf. Syst. 2016, 15, 320–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gladstein, D.L.; Reilly, N.P. Group decision making under threat: The tycoon game. Acad. Manag. J. 1985, 28, 613–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isenberg, D.G. Some effects of time pressure on vertical structure and decision-making accuracy in small groups. Organ. Behav. Hum. Perform. 1981, 27, 117–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hannah, S.T.; Uhl-Bien, M.; Avolio, B.J.; Cavarretta, F.L. A framework for examining leadership in extreme contexts. Leadersh. Q. 2009, 20, 897–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, M.K.; Haslam, S.A.; Hersby, M.D.; Bongiorno, R. Think crisis–think female: The glass cliff and contextual variation in the think manager–think male stereotype. J. Appl. Psychol. 2011, 96, 470–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mulder, M.; de Jong, R.D.; Koppelaar, L.; Verhage, J. Power, situation, and leaders’ effectiveness: An organizational field study. J. Appl. Psychol. 1986, 71, 566–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eagly, A.H.; Carli, L. Through the Labyrinth. The Truth about How Women Become Leaders; Harvard Business School: Boston, MA, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Gartzia, L. The Gendered Nature of (Male) Leadership: Expressive Identity Salience and Cooperation. In Best Paper Proceedings of the Academy of Management 2011. Available online: https://www.program.aomonline.org/2011/reportsaspnet/Proceedings.aspx (accessed on 30 March 2023).

- Kark, R. The transformational leader: Who is (s)he? A feminist perspective. J. Organ. Change Manag. 2004, 17, 160–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kark, R.; Waismel/Manor, R.; Shamir, B. Does valuing androgyny and femininity lead to a female advantage? The relationship between gender-role, transformational leadership and identification. Leadersh. Q. 2012, 23, 620–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loughlin, C.; Arnold, K.; Bell-Crawford, J. Lost opportunity: Is transformational leadership accurately recognized and rewarded in all managers? Equal. Divers. Incl. Int. J. 2012, 31, 43–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avolio, B.J.; Walumbwa, F.O.; Weber, T.J. Leadership: Current theories, research, and future directions. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2009, 60, 421–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barsade, S.G.; Gibson, D. Why does affect matter in organizations? Acad. Manag. Perspect. 2007, 21, 36–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayer, J.D.; Roberts, R.D.; Barsade, S.G. Human abilities: Emotional intelligence. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2008, 59, 507–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaccaro, S.J. Trait-based perspective. Am. Psychol. 2007, 62, 7–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boehm, A.; Enoshm, G.; Shamai, M. Expectations of grassroots community leadership in times of normality and crisis. J. Contingencies Crisis Manag. 2010, 18, 184–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koene, A.S.; Vogelaar, L.W.; Soeters, J.L. Leadership effects on organizational climate and financial performance: Local leadership effect in chain organizations. Leadersh. Q. 2002, 13, 193–215. [Google Scholar]

- James, E.H.; Wooten, L.P.; Duskek, K. Crisis management: Informing a new leadership research agenda. Acad. Manag. Ann. 2011, 5, 455–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- James, E.H.; Wooten, L.P. Leading Under Pressure: From Surviving to Thriving Before, During, and After a Crisis; Routledge: London, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

| Examples of the Coding Procedure | ||

|---|---|---|

| Statement | Core Statement | Category |

| The leader kept telling us to do our job and leave the worries to him. | a sense of support and security | empathy and care (EC) |

| To me, the most important thing was honest communication […]. I wanted to know where I stood, even if I had to find out we were finally closing the hotel. | being informed | transparency and communication (TC) |

| Characteristics of Hotel Employees | ||

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Female | 129 | 63% |

| Male | 75 | 37% |

| Age | ||

| 20–29 | 44 | 21.8% |

| 30–39 | 69 | 33.4% |

| 40–49 | 53 | 25.8% |

| 50–59 | 35 | 17.6% |

| ≥60 | 3 | 1.4% |

| Position | ||

| Front desk | 59 | 28.9% |

| Event planning | 28 | 13.7% |

| Hotel administration | 30 | 14.7% |

| Housekeeping | 45 | 22.1% |

| Hotel kitchen | 25 | 12.3% |

| Food service | 16 | 7.8% |

| Support staff | 1 | 0.5% |

| Years of working experience in hospitality | ||

| ≤1 | 29 | 14.2% |

| 1–2 | 49 | 24.0% |

| 2–5 | 39 | 19.1% |

| 5–10 | 61 | 29.9% |

| ≥10 | 26 | 12.7% |

| Hotel details | ||

| Number of employees | ||

| 1–10 | 4 | 11.4% |

| 11–20 | 17 | 48.6% |

| 21–50 | 14 | 40.0% |

| Number of rooms | ||

| 1–10 | 2 | 5.7% |

| 11–20 | 11 | 31.4% |

| 21–50 | 10 | 28.6% |

| 51–100 | 8 | 22.9% |

| 101–150 | 4 | 11.4% |

| Category | ||

| ** | 6 | 17.1% |

| *** | 18 | 51.4% |

| **** | 11 | 31.4% |

| 1. Do you consider your manager a leader? 2. What qualities make your manager a leader? 3. What does s/he lack to be considered a leader? 4. What behaviors or decisions of your manager do you remember as particularly important (positive or negative) during the pandemic and the hotel closure period? Why did you remember them as important? 5. Give examples of your manager’s leadership behaviors that had a particularly strong impact on the feelings of the team as a whole? What comments did your colleagues make at that time? 6. Does the list of leadership qualities that I am about to show you now reflect your manager’s attitudes in any way? 7. Try to match the behaviors and decisions you have listed in points 4 and 5 with the leadership qualities you see on the list. 8. Name the three leading features of your manager that had the greatest impact on your decision to stay in/change your job during the pandemic? |

| Main Categories of Staff Statements | Leadership Category |

|---|---|

| I felt that our hotel was ours, and the team was more than just co-workers. | EC, ICE |

| I felt safe, and I had a sense of support. | EC |

| Our needs were quickly discussed and addressed, even if concerned non-professional matters. | EC, DR |

| Private, family, and health problems were treated with attention and care. | EC |

| The effects of the lockdown in the private sphere were treated as seriously as the issues of hotel operation. | EC |

| Constant contact with employees was maintained (online or on-site). | EC |

| We were posted on the situation. | TC |

| The staff responded well to honest information, even if it was unfavorable. | TC |

| Factual communication of tasks was very important to us. | TC |

| We understood what we had to do. | TC, DR, A |

| The leader did not formulate unrealistic expectations but constantly ensured that each of us was kept busy. | DR, A |

| We were looking for new opportunities and opportunities to act and earn money—it was interesting and inspiring. | A, ICE |

| Even with zero occupancy, we knew what to do—it relieved frustration. | DR, ICE, A |

| We liked the unconventional approach to the business model. | A |

| I felt the leader knew what to do. | DR |

| We received frequent messages saying that we would deal with the crisis together. | DR, RC, A |

| The leader worked harder than usual but tried to keep calm in relations with its employees. | DR, RC |

| The leader openly informed us about negative government decisions and subsequent restrictions. | RC |

| The leader was able to talk about his/her mistakes and failures without hesitation—(s)he apologized to us and asked for advice; it motivated us a lot. | RC, ICE |

| The leader took responsibility for the economic situation of our hotel, even if it was in no way dependent on his/her/its decisions. | RC |

| I liked that (s)he made decisions without hesitation. | DR, RC |

| Quick decisions were important to me—every delay made me afraid. | DR, RC |

| Decisive actions made me act more willingly and think less about the general situation. | DR |

| Any new development, regulation change, etc., were immediately discussed with the team. | ICE |

| We were free to express our concerns about the activities undertaken at the hotel. | ICE, TC |

| The staff was encouraged to cooperate also in the area of personal problems. | ICE, EC |

| The leader identified our “secret powers”—it was interesting that such great people work in our team! | ICE, A |

| The leader willingly listened to our comments and ideas. | ICE |

| The contribution of each of us to solving problems was appreciated | ICE |

| Reported Situations | Hotels | F/M/N | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | % | No. | % | ||

| Inclusivity, collaboration, and empowerment (ICE) | 189 | 93% | 27 | 77% | F |

| Empathy and care (EC) | 104 | 51% | 23 | 66% | F |

| Transparency and communication (TC) | 76 | 37% | 18 | 51% | F |

| Resilience and courage (RC) | 59 | 29% | 9 | 26% | M |

| Adaptiveness (AD) | 54 | 26% | 11 | 31% | N |

| Decisiveness and risk-taking (DR) | 47 | 23% | 12 | 34% | M |

| Hotel | 2019 | 2020 | PP Change | Leadership Style | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| F | M | N | ||||

| 1 | 12% | 11% | −1% | 51% | 40% | 9% |

| 2 | 18% | 29% | 11% | 10% | 78% | 12% |

| 3 | 8% | 8% | 0% | 67% | 19% | 14% |

| 4 | 6% | 5% | −1% | 39% | 43% | 18% |

| 5 | 11% | 11% | 0% | 72% | 16% | 12% |

| 6 | 14% | 14% | 0% | 71% | 20% | 9% |

| 7 | 7% | 8% | 1% | 64% | 22% | 14% |

| 8 | 6% | 6% | 0% | 61% | 28% | 11% |

| 9 | 9% | 10% | 1% | 77% | 15% | 8% |

| 10 | 12% | 14% | 2% | 83% | 3% | 14% |

| 11 | 17% | 33% | 16% | 17% | 65% | 18% |

| 12 | 13% | 15% | 2% | 66% | 9% | 25% |

| 13 | 10% | 9% | −1% | 59% | 23% | 18% |

| 14 | 6% | 12% | 6% | 65% | 21% | 14% |

| 15 | 16% | 28% | 12% | 18% | 73% | 9% |

| 16 | 7% | 8% | 1% | 57% | 27% | 16% |

| 17 | 14% | 15% | 1% | 61% | 25% | 14% |

| 18 | 18% | 27% | 9% | 56% | 31% | 13% |

| 19 | 6% | 7% | 1% | 66% | 30% | 4% |

| 20 | 5% | 7% | 2% | 71% | 13% | 16% |

| 21 | 4% | 6% | 2% | 57% | 29% | 14% |

| 22 | 21% | 22% | 1% | 81% | 16% | 3% |

| 23 | 13% | 30% | 17% | 33% | 54% | 13% |

| 24 | 12% | 11% | −1% | 36% | 53% | 11% |

| 25 | 11% | 11% | 0% | 63% | 23% | 14% |

| 26 | 8% | 19% | 11% | 24% | 61% | 15% |

| 27 | 13% | 10% | −3% | 77% | 9% | 14% |

| 28 | 6% | 4% | −2% | 72% | 14% | 14% |

| 29 | 14% | 27% | 13% | 39% | 55% | 6% |

| 30 | 9% | 11% | 2% | 60% | 29% | 11% |

| 31 | 4% | 3% | −1% | 77% | 5% | 18% |

| 32 | 23% | 26% | 3% | 43% | 44% | 13% |

| 33 | 4% | 5% | 1% | 55% | 38% | 7% |

| 34 | 8% | 7% | −1% | 34% | 55% | 11% |

| 35 | 10% | 11% | 1% | 64% | 27% | 9% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kachniewska, M.; Para, A. Feminine vs. Masculine: Expectations of Leadership Styles in Hotels during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Sustainability 2023, 15, 10602. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151310602

Kachniewska M, Para A. Feminine vs. Masculine: Expectations of Leadership Styles in Hotels during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Sustainability. 2023; 15(13):10602. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151310602

Chicago/Turabian StyleKachniewska, Magdalena, and Anna Para. 2023. "Feminine vs. Masculine: Expectations of Leadership Styles in Hotels during the COVID-19 Pandemic" Sustainability 15, no. 13: 10602. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151310602

APA StyleKachniewska, M., & Para, A. (2023). Feminine vs. Masculine: Expectations of Leadership Styles in Hotels during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Sustainability, 15(13), 10602. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151310602

_Li.png)