1. Introduction

The Framework Convention on the Value of Cultural Heritage for Society, commonly known as Faro Convention, safeguards cultural heritage as “a group of resources inherited from the past which people identify (…) as a reflection and expression of their constantly evolving values, beliefs, knowledge and traditions” encompassing “all aspects of the environment resulting from the interaction between people and places through time” [

1] (p. 2).

In line with this perspective, cultural heritage is closely tied to place and community identity, serving as the visible or narrative foundation of the psycho-social bond between individuals and their immediate surroundings. Expanding on this viewpoint, the preservation of intangible local heritage is also intimately connected to sustainability when conceptualized as an interdependent system of environmental, economic, and social factors. Heritages act as a catalyst for environmental preservation, community cohesion, and economic attractiveness within a neighborhood. These principles have been widely applied in urban regeneration policies, both in the European Union and elsewhere, since the 1990s. Numerous culture-led regeneration programs have been implemented to enhance quality of life and well-being through re-signification and re-appropriation processes involving local heritages [

2]. The relationship between the cultural heritage and identity and/or well-being of communities has been extensively investigated in the social sciences, exploring various subtopics. From a community perspective, a recent study [

3] on urban (deprived) areas has argued that local artistic heritages play an enabling role in fostering civic engagement among citizens and NGOs by strengthening place identity [

4] and community cohesion. According to Hull et al. [

5], local heritages are recognized by residents as icons that embody memories and meanings associated with the subjective sense of belonging to the community and its distinctive character, hence representing a link with the past. Furthermore, social values attributed to the local artistic heritage have been found [

6] to be the main discriminant driving citizens’ reactions to human-made place disruptions, such as heavy urban transformations in historic urban centers. Heritages have also been addressed within the “restorative environments” framework [

7], with studies pointing out that the psychological benefits typically associated with natural environments, such as attention restoration and stress reduction, are found in built environments of historical and social significance [

8], including city centers [

9,

10], monasteries [

11], and museums or art galleries [

12].

Public and scientific attention have been recently paid, in particular, to another related subtopic, concerning the crucial role of contemporary art heritage in processes of city renewal and urban area rebranding. Since the final decades of the twentieth century, this line of research has gained popularity in the context of the ongoing transition from industrial urban forms to post-industrial ones in European and North American cities, which is also largely driven by the aforementioned culture-led programs. As summarized by several authors [

13,

14], studies have highlighted the benefits of artistic and creative processes as triggers for developing new social, identity, and economic potential in targeted areas in different cultural contexts [

15,

16,

17]. However, these art-driven regeneration processes can have negative side effects, such as promoting gentrification and reinforcing urban “cosmetics” programs without tangible improvements for the local population’s well-being, causing both a significant loss in the sense of community and the erosion of local cultural traditions that take place in the absence of a dialogue between old inhabitants and newcomers [

18,

19,

20,

21]. The use of street art, mainly wall paintings, in urban renewal processes is a case in point of the potential positive and negative outcomes of such processes. It is widely adopted due to its affordability, high visual and communicative impact, resonance with the aesthetic taste of the creative class and youth populations, and its strong and immediate association with urbanity and territorial dynamism in the common sense. According to Santamarina-Campos et al. [

22], the process of the institutionalization of street art is nowadays completed as this “industry” currently produces, in Europe alone, 180,000 new works every year. Similarly, scholars [

23,

24] have spoken of the “artification” of graffiti and urban wall paintings, where a social practice born as anti-systemic and illegal has over time become an accepted and commercialized artistic phenomenon.

From a psychological point of view, the research on wall paintings and contemporary street art has been limited, focusing primarily on specific areas. In the field of development studies, it has been pointed out that belonging to groups of writers can play a crucial role in the self-definition process during adolescence, with reference to degraded urban areas. Moreover, the acquisition of skills in the field of street art can enhance the development of self-esteem and creativity among young people living in socially deprived contexts [

25,

26].

In terms of the community perspective, scholars have asserted that graffiti and wall paintings are generally perceived by the insiders, both creators and members of their extended local group, as a declaration of belonging to a territorially rooted (sub-) culture, reinforcing the sense of community [

27]. Aligning with broader research on heritages, street art has also been identified among the factors contributing to psychological wellbeing and restoration while walking in urban environments, as it can be strongly associated with the city identity, evoking feelings of civic pride [

28]. Surprisingly, despite the implicit assumption in other disciplinary fields (e.g., design, urban policies) that street art has a positive effect on identity, there is currently a lack of psychological studies specifically measuring the potential impact of street-art-based projects on place attachment and/or place identity.

From another viewpoint, usually referring to the Broken Window Theory [

29], urban crime research has emphasized that street art, particularly spontaneous graffiti and tags, can be interpreted as one of the main signs of local incivilities, leading to a stronger sense of insecurity, lack of respect for social norms, and fear of crime [

30,

31]. Furthermore, adopting a cognitive-based approach, Motoyama and Hanyu [

32] have argued that public contemporary art is generally associated with an increased perception of complexity and emotional arousal in urban spaces, while the level of pleasantness largely depends on the type of artwork created.

In the Italian context, the trends already highlighted in the international literature are confirmed. The few studies conducted so far, mainly taking a sociological approach, have depicted an oscillation between processes of regeneration, fruitful territorial reappropriation [

33], and paths of gentrification and “urban make-up” through street art [

34]. Italy has witnessed the institutionalization of street art through various themed projects funded by public administrations in the largest cities, either independently or as part of wider urban regeneration programs.

To the best of our knowledge, no longitudinal psycho-social research has been conducted in Italy or elsewhere to examine the medium–long term impact of street-art-based regeneration programs on the relationship between citizens and the target neighborhood. In comparison to existing literature, our work focuses on a case study where regeneration interventions predominantly involve the creation of wall paintings. Thus, the “street art” variable can be considered as an “in vivo” independent variable. Specifically, this exploratory study aims to investigate if and to what extent the use of street art as a regenerative factor contributes to the preservation of local intangible cultural heritages and affective ties, five years after the initiation of the urban renewal project. To assess the impact of these interventions, we concentrate on two main concepts. The first concept is the neighborhood-related image, which originates from the field of urban planning and is defined as a mental representation emerging from continuous experiences within a place. This image constantly evolves based on collective interactions among people attending a place, hence, it can vary over time in response to environmental and social events occurring in an area [

35]. The second concept is place attachment, a construct that refers to the affective people–place bond [

36], which encompasses cognitive and behavioral aspects such as maintaining proximity to the place itself [

37,

38]. Place features influencing such attachment include both physical and symbolic elements, and it is also viewed as a temporal phenomenon developing over a certain period. Furthermore, two distinct populations, namely residents and non-residents, are included in the study to highlight any significant differences between those who live in the neighborhood on a daily basis and those who visit occasionally for work or leisure.

2. Case Study

The Ortica neighborhood represents a distinctive case study due both to its significant cultural heritage, inherited from the twentieth century, and the type of urban renewal project implemented in this context.

Historically, Ortica was a rural village for several centuries, deriving its name from the word “orto”, meaning “vegetable garden” in Italian. It gradually became incorporated into the city of Milan in the early twentieth century, with the establishment of a large railway yard in the vicinity. Due to its strategic position on the periphery of the city, the neighborhood experienced heavy industrialization from 1930 to 1970, including the presence of the Innocenti factory, which employed up to 7000 workers during World War II. This period witnessed the development of a robust working-class identity in the neighborhood. This was shaped by residents’ employment in factories and railways, as well as the proliferation of community organizations with a predominantly socialist and anti-fascist character.

However, since the late 1970s, Ortica has undergone a process of deindustrialization, leading to the emergence of abandoned areas and shrinking processes, similar to many other working-class neighborhoods. Despite this, the milieu of community organizations in the area has generally remained active. Furthermore, the residential parts of the neighborhood have not undergone significant urban transformations due to their partial isolation, resulting from the surrounding railway and road layout.

The Ortica neighborhood is located in the eastern periphery of Milan, primarily falling within the administrative unit known as NIL (Nucleo d’Identità Locale—Local Identity Unit) 23 “Lambrate”, since the main northern section is covered by the Lambrate neighborhood. A small portion of the neighborhood is included in NIL 24 “Parco Forlanini—Ortica” (

Figure 1). NILs are administrative divisions that represent areas that are formally conceived as neighborhoods in Milan, recognized by the institutions responsible for territorial management as having unique historical and heritage characteristics. In 2011, eighty-eight NILs were defined by the PGT (Piano di Governo del Territorio—Territorial Government Plan) as areas featuring local businesses, gardens, gathering places, and services; they serve as reference points for institutions to strengthen local identity and design community services (Municipality of Milan,

https://www.pgt.comune.milano.it/psschede-dei-nil-nuclei-di-identita-locale/nuclei-di-identita-locale-nil, accessed on 28 May 2023). Despite the institutional effort to highlight locally relevant identities, the Ortica neighborhood is divided between two separate NILs.

The available data on the neighborhood (

Table 1) also reflect this division, as the information was collected only in the NIL level over a historical period. Analyzing NIL 23 (2012 and 2022), which encompasses the most populous section of Ortica, one can observe the current trend of an aging population and an increase in the number of single-person households, while gender distribution remains relatively stable. These trends align with those observed in the city of Milan as a whole. However, the decrease in the number of foreign residents, contrary to the average trend in the broader city, could suggest the influence of ongoing gentrification processes in the area, as well as the general increase in the number of residents. It is worth noting that the population density in the NIL is approximately half that of the entire city.

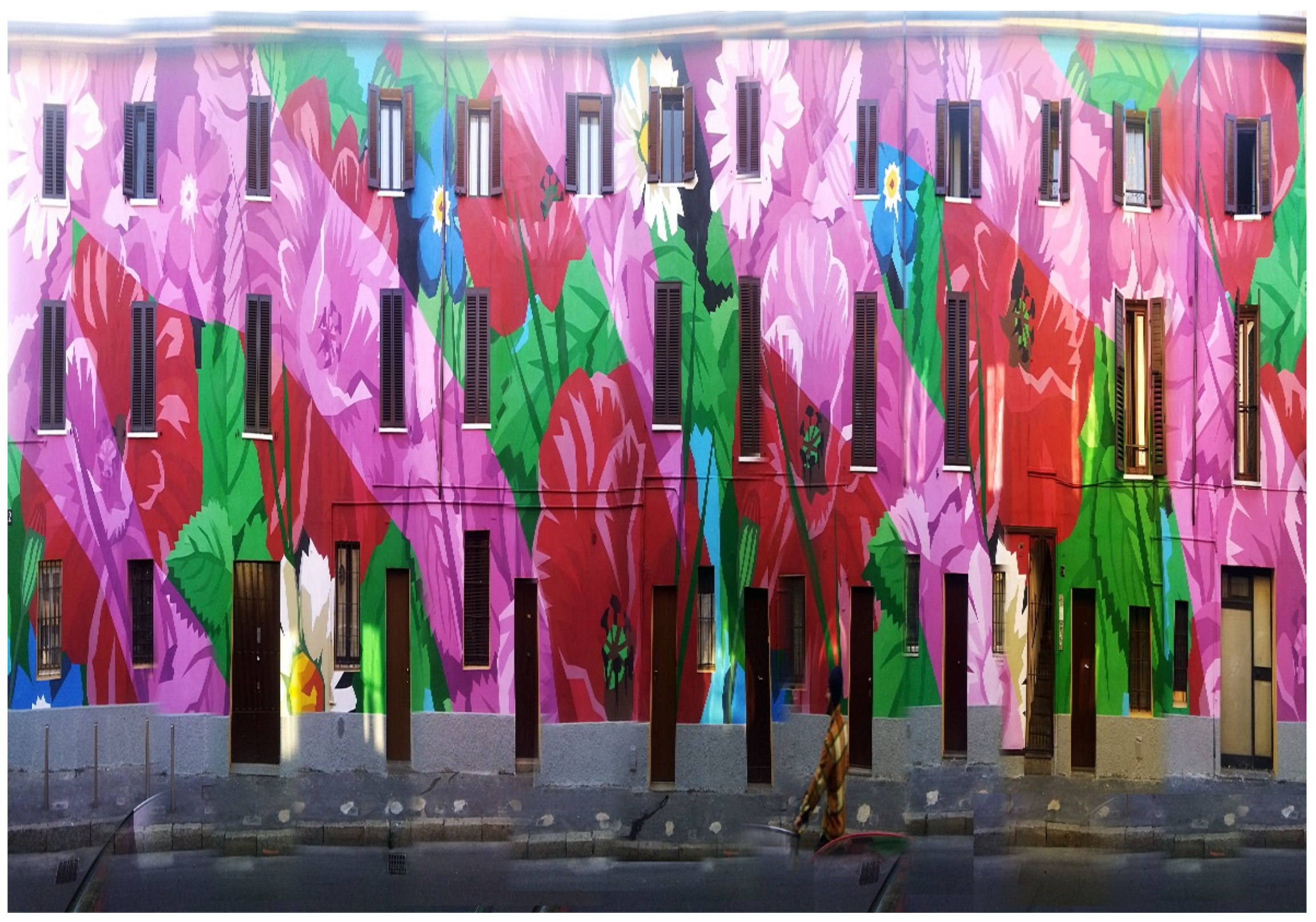

In 2017, the OrMe—Ortica Memoria association—was established by local stakeholders (“orme” meaning “footsteps” in Italian). The association initiated a series of initiatives with the objective of creating an open-air and freely accessible neighborhood museum where “the history of the Italian 20th century is painted on the walls” (

https://orticamemoria.com/, accessed on 28 May 2023). The project involves the collaboration of the OrticaNoodles, a collective of local street artists with extensive national and international experience who are deeply rooted in the neighborhood. Their primary goal is to directly narrate the history and identity of the Ortica neighborhood through the creation of 20 large-scale urban artworks, specifically wall paintings (see

Figure 2,

Figure 3,

Figure 4 and

Figure 5), which aim to foster positive relationships between civic participation, media visibility, and tourist attraction. The project is currently ongoing, and the completed artworks cover various themes such as cooperation and unions, music and sociability, work and rights, women, and sport, with significant references to local history. The artworks are strategically positioned throughout the Ortica neighborhood, encompassing the southern part of NIL 23 and the northern part of NIL 24. This distribution partially deviates from the institutional representation of the spatial allocation designated for local cultural heritage (

Figure 6). Notably, the project’s distinctive aspect lies in its participatory approach, employing stencil art techniques to facilitate the direct involvement of local actors in the painting process even in the absence of specific art skills.

4. Results

4.1. Neighborhood-Related Image

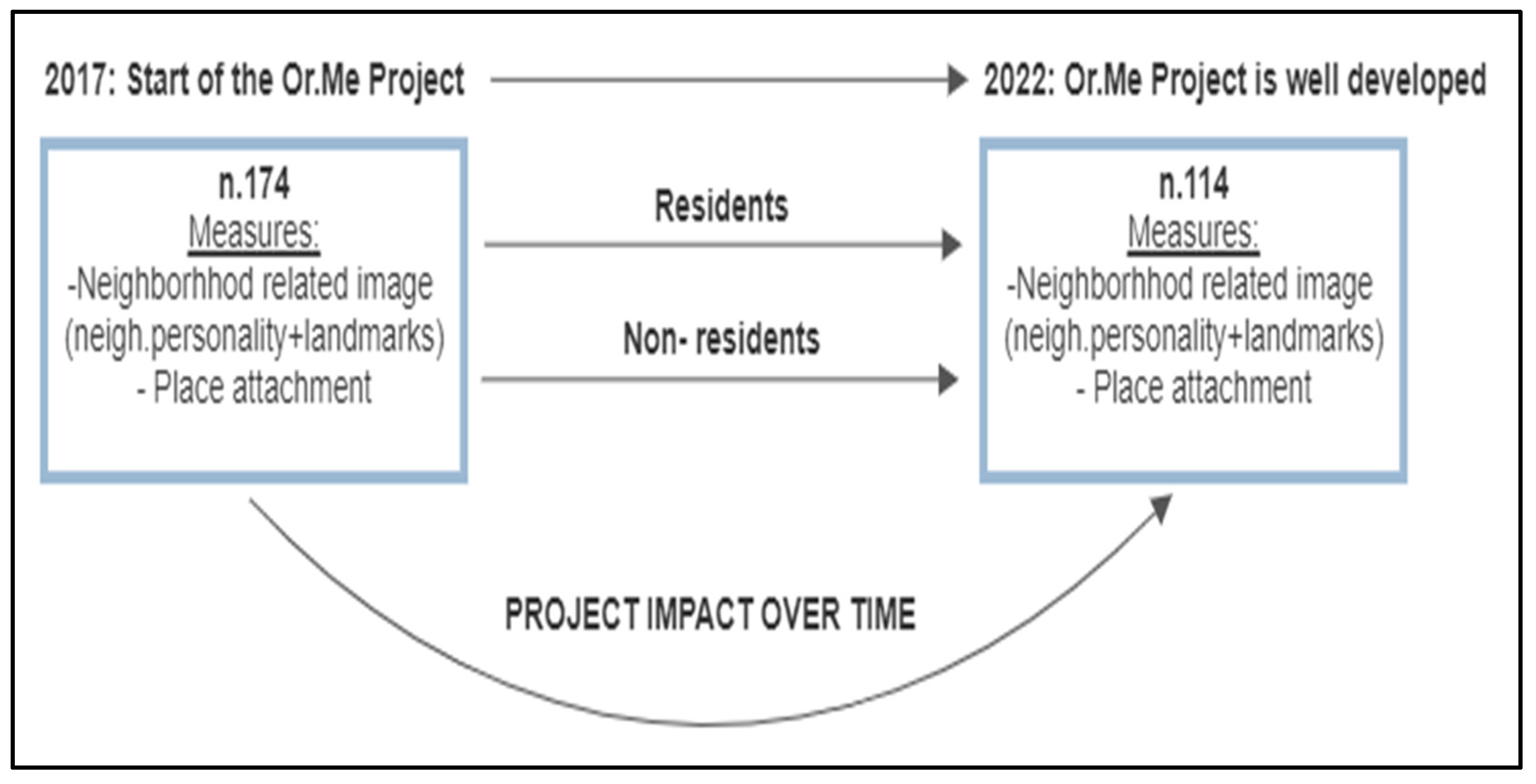

A t-test was conducted on two independent samples (1 and 2) to assess whether significant variations occurred in the local image (“personality” characteristics attributed to the neighborhood) between 2017, when the “OrMe Project” commenced, and 2022, when the project was extensively developed and well known among residents and city users. The average knowledge about the project increased from 1.83 (sample 1 N = 174, SD = 0.950), to 2.34 (sample 2 N = 114, SD = 1.143) over time (t (286) = −4.097, p < 0.01).

Regarding the general population, the results showed significant positive variations in dynamism (sample 1 M = 2.42, sample 2 M = 2.73; t (252) = −2.968, p < 0.01), sociability (sample 1 M = 2.58, sample 2 M = 2.84; t (250) = −2.539, p < 0.05), innovation (sample 1 M = 2.40, sample 2 M = 2.79; t (252) = −3.774, p < 0.001), and creativity (sample 1 M = 2.72, sample 2 M = 3.22; t (251) = −4.699, p < 0.001) in favor of 2022. Conversely, there have been no significant changes in the perception of quality of life (sample 1 M = 2.89, sample 2 M = 2.86; t (240) = 0.316, p = 0.75) and the importance of local traditions (sample 1 M = 2.76, sample 2 M = 2.88; t (243) = −0.967, p > 0.05).

When controlling for “residence”, the data showed the crucial relevance of this factor. Among residents, significant variations in favor of 2022 were observed for all variables (see

Table 2). On the other hand, non-residents did not exhibit such variations, although higher average values were observed for 2022 compared to 2017 in this population as well. Specifically, the following variations in the residents’ group were reported for the local image: dynamism (sample 1 M = 2.28, sample 2 M = 2.84;

t (117) = −3.793,

p < 0.001), sociability (sample 1 M = 2.58, sample 2 M = 3.16;

t (117) = −3.675,

p < 0.001), innovation (sample 1 M = 2.37, sample 2 M = 2.97;

t (117) = −3.668,

p < 0.001), creativity (sample 1 M = 2.58, sample 2 M = 3.50;

t (117) = −6.081,

p < 0.001), quality of life (sample 1 M = 3.01, sample 2 M = 3.39;

t (115) = −2.593,

p < 0.05), and importance of local traditions (sample 1 M = 2.77, sample 2 M = 3.24;

t (113) = −2.541,

p < 0.05).

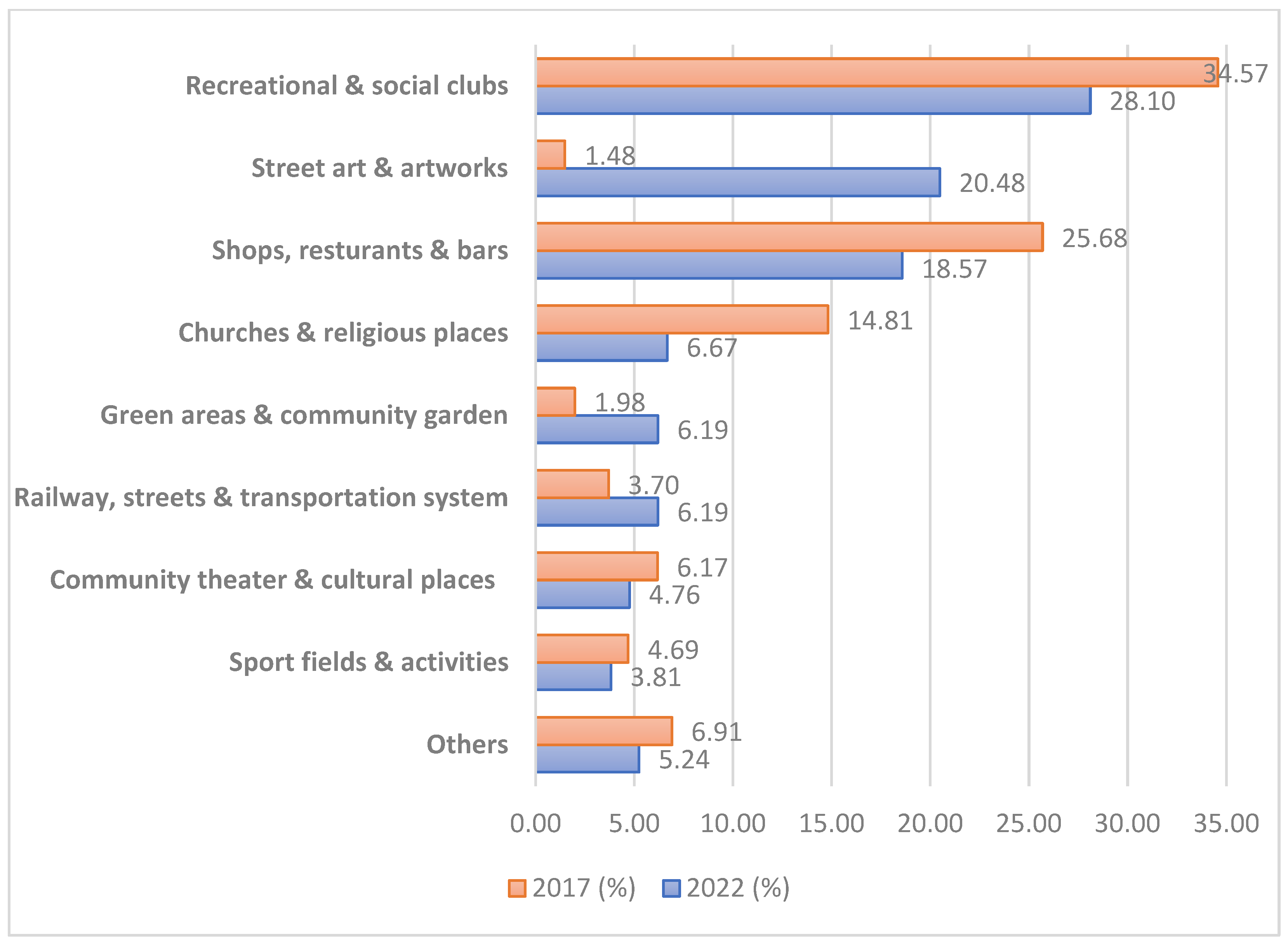

Furthermore, the neighborhood’s image was further investigated through a landmark analysis (see

Figure 8) to verify if there were any substantial changes between 2017 and 2022. The participants’ selections of landmarks were categorized into the following functional groups:

- (1)

Recreational & social clubs: recreational places with mixed functions that characterize the social fabric of the neighborhood (e.g., dance halls, cooperative clubs).

- (2)

Street art &artworks: includes all references to the artworks created in the neighborhood.

- (3)

Shops, restaurants & bars: retail and dining services (e.g., bars, ice cream shops).

- (4)

Green areas & community gardens.

- (5)

Railways, streets & transportation systems: includes references to railway and transportation lines, public transportation stops, and specific streets within the district.

- (6)

Community theater & cultural places: encompasses theaters, cinemas, and other spaces dedicated to cultural production and consumption within the neighborhood.

- (7)

Sport fields & activities.

- (8)

Others: includes poorly selected activities that cannot be categorized into the other groups.

The comparative results (combining both samples, with a total of 405 and 210 landmark nominations, respectively) showed a significant increase in the prominence of street art works created within the OrMe Project in the local image. In 2017, they accounted for a mere 1.48% of all mentioned landmarks (six nominations), but by 2022 they became the second most frequently cited category at 20.48% (43 nominations; χ2(1) = 48.84, p < 0.01). Consequently, a decrease in the presence of other landmark categories was observed, although they remained highly significant for the citizens.

Specifically, the most frequently cited landmarks remained those related to recreational and social clubs, both in 2017 (34.57%, 140 nominations) and in 2022 (28.1%, 59 nominations; χ

2(1) = 2.65,

p > 0.05). Similarly, neighborhood shops and bars/restaurants were still considered relevant, although their prominence decreased from 25.68% in 2017 (104 nominations) to 18.57% in 2022 (39 nominations; χ

2(1) = 3.91,

p < 0.05). Importantly, there was a significant increase in references to green areas (from 1.98% to 6.19%, eight and 13 nominations; χ

2(1) = 7.45,

p < 0.01), including a community garden recently established in the neighborhood [

40,

41]. Finally, due to the lower average age in the second sample, a decrease in references to religious places was notable (from 14.81% to 6.67%, 60 and 14 nominations; χ

2(1) = 8.67,

p < 0.01).

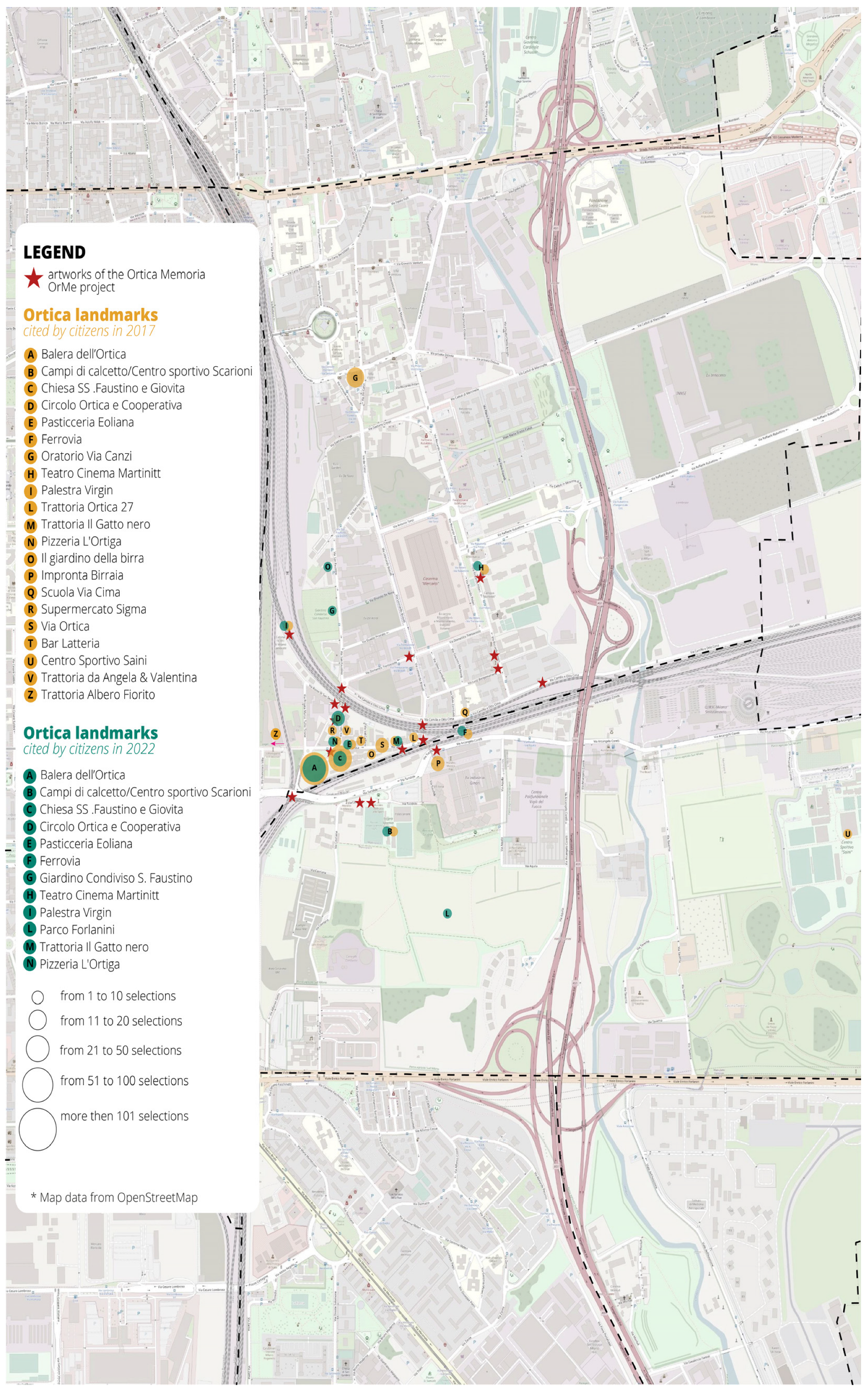

4.2. Spatial Distribution of the Landmarks

A further analysis of the landmarks mentioned by citizens examined their spatial distribution, representing the selected elements on a map (

Figure 9). It is noteworthy that all of the landmarks are located in the area historically identified as Ortica, with a particular concentration around the railway. The distribution extends beyond the boundaries of the institutional NILs, encompassing the southern part of NIL 23 Lambrate and the northern part of NIL 24 Parco Forlanini—Ortica.

4.3. Place Attachment

A two-sample t-test was conducted to test the null hypothesis that place attachment was equal in 2017 and 2022. Initially, the analysis was performed on the entire sample, and then it was controlled for the residence factor. The results closely mirrored those obtained for the local image, revealing no significant differences in the general population (sample 1 M = 2.63, SD = 0.825, N = 140; sample 2 M = 2.52, SD = 0.931, N = 115; t (253) = 1.074, p > 0.05) (mean 2.52 vs. 2.67; p = 0.188). However, when considering only residents, significant differences in place attachment emerged (sample 1 M = 2.85, SD = 0.811, N = 81; sample 2 M = 3.39, SD = 0.756, N = 38; t (117) = −3.507, p < 0.001), favoring the year 2022.

Furthermore, the correlation between the self-perceived level of knowledge about the Ortica Memoria Project in the general population and place attachment was calculated. The results revealed a significant correlation in both 2017 (r = 0.371; p < 0.01) and 2022 (r = 0.575; p < 0.01), with a stronger relationship observed in 2022. When controlled for years of residence, these results remained significant (sample 1 r (85) = 0.287; p < 0.01; sample 2 r (42) = 0.409; p < 0.01).

5. Discussion

This study represents the first longitudinal assessment of the impact of a street-art-based neighborhood renewal project on citizens’ neighborhood image and place attachment. The findings indicate a significant improvement in the local image, emphasizing territorial attributes such as dynamism, sociability, innovation, and creativity (

Table 1). It can be argued that, while the ongoing street-art-based project promotes a contemporary vision of the neighborhood (dynamism, innovation, and creativity) aligned with its goals of reinforced sociability, it has not significantly affected aspects related to the neighborhood’s history and traditions nor the perceived quality of life, as indicated by the lack of variation between 2017 and 2022 on these dimensions in our general sample (p. 10). Notably, residents experience more pronounced positive effects compared to non-residents, perceiving a significant increase in the importance of local traditions and quality of life five years after the project’s initiation. Overall, we consider the OrMe project effective in conveying a sense of revitalization of the neighborhood’s image through the creation of paintings and their exposure to the general population via various media. Although the project has had a positive impact on the wider population of Milanese residents, it only partially aligns with the project’s overall goals. By contrast, neighborhood residents have experienced a more diverse and comprehensive effect during the observed period. Alongside the presence of paintings and media communication, Ortica residents have actively participated in the creation of artworks and are routinely exposed to the aesthetic transformation of the neighborhood in their daily lives. As a result, their perception of the neighborhood has improved in a harmonious way, integrating both contemporary and traditional elements, as intended by the project, without causing significant displacement feelings or loss of the neighborhood’s identity, as observed elsewhere [

38].

The findings related to the spontaneous selection of landmarks in the neighborhood support this observation, indicating that the murals from the OrMe project have become part of the local “cognitive map” without replacing other established reference points tied to the neighborhood’s social history, such as recreational clubs, bars, and gathering places. As mentioned earlier, the growth in the impact of wall paintings (from 1.48% to 20.48%) does not overshadow the presence of existing landmarks. When combined, these landmarks still account for approximately 80% of the reported observations by the participants. This highlights the project’s key strengths, including its progressive nature, its reflection of the neighborhood’s history, and its implementation in partnership with local associations.

Considering such aspects in association with the spatial distribution of the landmarks cited by citizens is highly relevant. The entire set of landmarks, including artworks and other categories relevant to neighborhood identity, covers an area that extends from the southern part of NIL 23 Lambrate to the northern part of NIL 24 Parco Forlanini—Ortica. Despite institutional efforts to represent local relevant identities corresponding to historical neighborhoods, in citizens’ perception Ortica is still divided between two different institutional partitions. These partitions do not adequately capture the nuanced local community perception. Interestingly, the OrMe project seems to effectively address this aspect, as the distribution of artworks aligns closely with citizens’ perception of the neighborhood boundaries. From this perspective, the project appears consistent with local perception, not only in terms of the subjects selected for the artworks but also for their spatial characteristics.

Regarding place attachment, the data confirm a different pattern between residents and non-residents five years after the initiation of the OrMe project. While non-residents show no significant changes, residents exhibit a significant increase in their attachment to the area (from M = 2.85 to M = 3.39, p < 0.001). This suggests that while the project has brought contemporarily oriented aesthetic innovation to the neighborhood for the general population, this is not necessarily associated with an increased emotional bond with the area. Conversely, Ortica residents have experienced heightened attachment levels coupled with a perceived reinforcement of both the innovative and traditional qualities of the neighborhood. This positive effect can be attributed to the themes addressed in the street art, which are closely connected to the neighborhood’s past and its community history, as well as to the engagement process during the actual production of the paintings. Moreover, further analysis reveals a strong correlation between citizens’ awareness of the OrMe project and their perceived attachment to the neighborhood. This relationship remains significant (r = 0.371, 2017 and r = 0.575, 2022; p < 0.01) even when controlling for the years of residence (r = 0.287, 2017 and r= 0.409, 2022; p < 0.01). This implies that having a good knowledge of the project is a beneficial factor in terms of residents’ attachment to the area, regardless of the duration of their residency.

An alternative explanation for this effect on place attachment, according to Anton & Lawrence [

42], could lead us to speculate that residents perceive the neighborhood as threatened by the ongoing changes, thereby developing a stronger attachment to it. However, this interpretation contradicts the findings regarding the image of Ortica, where dimensions of sociability, tradition, and quality of life do not appear to be endangered by the environmental transformations. Future research, covering a broader time frame, will allow for further investigation of these issues.

Despite the substantial uniqueness of the results, two limitations should be carefully considered. Firstly, due to the “in vivo” nature of our quasi-experiment, it is not possible to determine with certainty that the observed changes are exclusively attributed to the impact of the OrMe project. Nonetheless, the particular social and spatial composition of the neighborhood, where no profound urban and social changes have occurred recently, allows us to consider the project as the primary factor driving evolution in the area over the past five years and, thus, a substantial potential contributor to the observed changes in the residents’ neighborhood image and place attachment. Secondly, due to the sampling method, we cannot exclude the possibility of self-selection effects influencing the results. Future studies should involve a larger sample of participants, including a wider range of social and age groups.

6. Conclusions

According to our study, a street-art-based project can have a positive impact on a neighborhood by nurturing residents’ neighborhood-related image and attachment to the area. Such a project can allow for the development of a representation of the place that combines innovation and creativity, while preserving the traditional strengths and spatial landmarks associated with local history and culture. These findings have significant policy implications for cultural heritage conservation in urban renewal processes, particularly in historic working-class neighborhoods, which often face challenges related to loss of identity and spatial degradation despite their strong pre-existing associative and social milieu. Firstly, our findings suggest that integrating a neighborhood’s social history and cultural traditions into the renewal process can help residents to perceive ongoing changes as more harmoniously integrated into their place identity. This approach can prevent a perceived loss of social bonds with the community and mitigate the negative or grief-like feelings often associated with urban transformations in other contexts. Secondly, the absence of a radical physical urban transformation can be considered a protective factor for both cultural heritage and residents’ well-being. Artists’ choices to enhance existing architectural heritage by painting their walls can “historicize” these structures. This was the case, for example, for the main recreational club in the neighborhood (

Figure 4) and the side walls of the railway ballast (

Figure 3), which have been given iconic value, respectively, as a historical community landmark and as a gateway to access the neighborhood itself. Street art is an optimal tool for achieving these goals due to its strong visual impact and its ability to express content related to and imprinted on the heritage being protected. Furthermore, this process of “re-materialization” of local history can empower residents’ civic pride and enhance their perceived quality of life, in line with our findings and the conclusions of other studies [

43]. This could positively affect older segments of the population who are more rooted in the local context and may be more affected by the progressive loss of traditional elements of community identity.

Furthermore, our findings have broader implications for integrated policies on environmental and social sustainability. Safeguarding intangible heritage can contribute to improvements in neighborhood conditions, including quality of life and the economic status of residents. These results suggest that nurturing and preserving intangible heritage can contribute to a holistic approach to sustainable development, encompassing both cultural and socioeconomic aspects.

Lastly, our study confirms the heuristic potential of applying psychological analysis to urban transformation and heritage protection processes. The intangible cultural values associated with urban spaces are strictly connected with individual and group identities, and understanding their psychological correlates can contribute to more inclusive and effective urban renewal processes [

40], from pre-occupancy assessments to ongoing and post-occupancy evaluations, ensuring a comprehensive understanding of their impact.