4.1. Secondary Data Findings

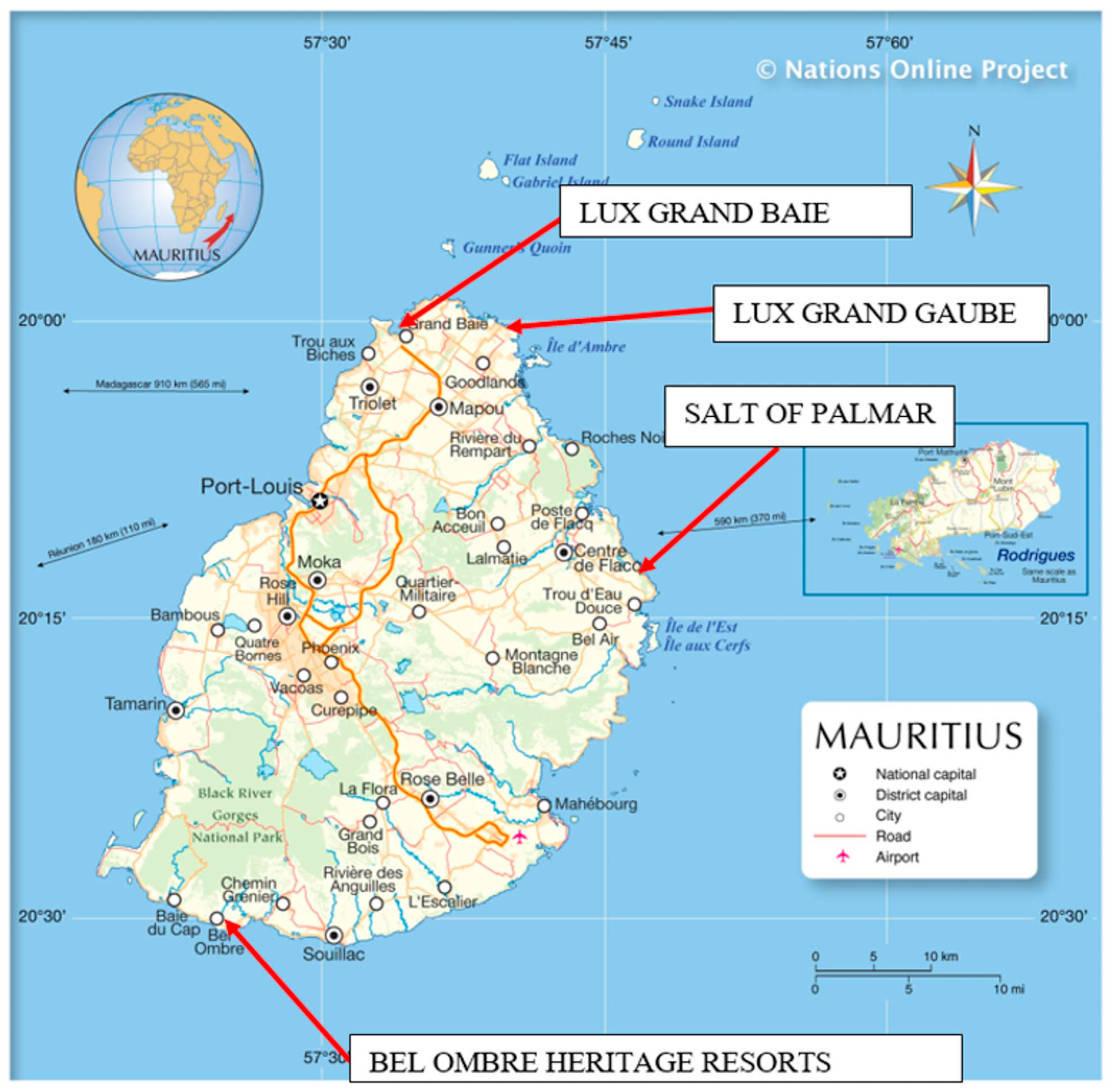

For the online analysis, four videos are considered, along with online materials indicating the ethos of the tourism establishment or reports on the establishment’s annual performance. The first encounter with the promotion of heritage discourse online was in the presentation of the Lux Hotel at Grand Gaube in the northeastern part of the island in 2021. The first video [

47] encountered (see the video still in

Figure 2) articulates the historical and tangible cultural heritage of Mauritius. The global doyenne of interior design, Kelly Hoppen, takes the online audience through the then-renovated Lux Belle Mare. Hoppen indicates that she wanted to create cocoons for the clientele, as well as a sense of privacy, exclusivity, and sensory experience. Access to the sensory heritage of Mauritius is apparent in the visual element of vernacular architecture; the tactile experience of local materials hints at intangible cultural heritage (ICH) in the behavior, values, and wellbeing treatments offered at the hotel. Visually, there are verandas, rattan patio furniture, and woven baskets, all of which signpost nostalgic remembrances of a pre-modern Mauritius. Hoppen’s narrative ties these narratives to the potential Lux client, a woman desirous of Independence and self-care, a person who desires seclusion from a relentless modernist existence. The narrative aligns with Otegui-Carles et al.’s [

48] substantive review of solo traveling, which confirms that solo traveling is increasing worldwide, and a substantive proportion of these travelers are women, who perceive this form of travel as a liberatory and potential source of mediated self-expression. Field research at the Lux Collective hotels (specifically Grand Baie) and at the Chateau de Bel Ombre revealed narratives of elite lifestyles and spheres of exclusivity [

49]. Not only do such “tourists” have curated leisure spaces, but they also access bespoke services that other, less influential and less wealthy travelers cannot access. As noted in this article, the health spa at Lux Grand Baie offers the experience of elite exclusivity; treatments are designed by globally renowned “traiteurs”, and the treatments are tailored for each client. At less exclusive hotels, the emphasis is on group benefits to reduce costs.

The second video, focused on Lux Grand Gaube, reveals a stronger effort to harness and articulate cultural heritage in the tourism space. In the Palm Court, a food dispensing area, there is the offering of diverse Mauritian cuisines, and clientele moves from one food station to another to literally encounter the taste heritage of Mauritius. Prospective clients are offered glimpses of the multicultural smorgasbord they could encounter if they booked to stay at the hotel. Through taste, décor, and curated spaces across the property, the cultural heritage of Mauritius is presented for a culturally specific experience in the same way that one would encounter a heritage site. The video of the solo woman tourist experiencing these restaurants also hints at liberatory practices. The woman in question is able to taste different cuisine, express an independent opinion on these, and inter alia reveal the culinary heritage of Mauritius.

Design decisions for a tourism establishment add to the palpability of the heritage experience. The video clearly highlights the distinctive nature of soft finishings, suggesting the possibility of “soft landings” for exhausted travelers. Chang [

50] adds that tourism studies should consider efforts to render destinations socially meaningful. He asserts that such socially meaningful destinations are part of a global lifestyle “turn”, “tourism accommodation has changed dramatically since the post-war period…today, a new genre of hotels strives to be known for their uniqueness. The holidays that tourists go on, the places that they visit, and the hotels in which they stay are increasingly a reflection of their individuality and distinctive lifestyle. The tourism industry has responded to this ‘lifestyle turn’. Hotels market their distinctiveness through unique interior décor, architectural styles, and personalized services. Many hotels sell ‘experiences’ that cannot be replicated elsewhere” [

47].

A 2016 European Travel Commission Report suggests that the lifestyle “turn” may be traced to experiences of an unfulfilled life. The Report adds that the search for “lifestyle” experiences is especially evident among long-haul travelers, who are now keen to combine self-improvement and experiential elements in their travels. Such travelers seek to fulfill personal, non-work-related desires in their chosen destinations. However, reading a popular reflection on the role of lifestyle in feminism, it was found that lifestyle expressions are an important first step in public feminist behavior [

24]. It is possible to extend the second view to this study. Women tourists, as imagined by Lux, are not merely there for the palpable potential heritage experience of the tourist site; they are also there to publicly express their feminist desires for freedom from social constraints and expectations. Considering the promotional videos for the Lux Collective in Mauritius, the narrative of the desire for fulfillment is apparent. The women represented in the videos appear to be traveling in search of freedom and existential authenticity [

25]. This is depicted in an online, publicly shared video [

51] regarding a group of women friends arriving at Lux Grand Baie in the North of the island (see video still,

Figure 3 below) to celebrate historical and present feminine ties and friendships. Lux Grand Gaube appears to offer this possibility, first through their adage of “lighter, brighter”, which encourages the clientele to live a heuristically enlightened existence and to tangibly feel lighter, less burdened by the oppressions of patriarchal impositions and values. This is captured in an online, publicly shared video [

52] of the quintessential Lux woman traveler, who supposedly stays healthy by drinking “greens”; however, as the video indicates, this is not a reality. Emancipated women travelers prefer to explore, live, enjoy, and be authentic. The story presented in the Lux Grand Gaube promotional video is that the women are pursuing sensory experiences of a kind that liberates them from daily, “normal”, potentially restricted experiences.

This is especially apparent in the video on the “Nomade”, a young, instagrammable woman who is depicted as an individual freeing herself from societal norms, such as the need to be disciplined in food and exercise habits, the need to be socially conscious and ecologically aware. The woman depicted is desirous of new experiences and unafraid to pursue these. The Nomade subverts the narrative of the socially approved woman who does what others expect. She expresses inconsistency, indecisiveness, poor choices, playfulness, and forgetfulness about propriety—she takes a holiday from patriarchal expectations. She appears to be in touch with her existence as a vulnerable human being desirous of new worlds and experiences. The Nomade is a contemporary woman navigating the challenges of living in an androcentric world where women are expected to conform to social mores of propriety, self-control, and ecological care. She is also a woman who, as in the publicly shared video promoting Lux Grand Gaube (see above), connects with long-forgotten female friends and recreates meaningful carefree (patriarchy-free) memories with them.

In subsequent tales of the Nomade, various kinds of people surface. The story unfolds diversity in the tourism setting in a landscape where diverse choices for play are realizable. The story is that one can be anything. One does not need to be authentic and relatable to be valuable. As an interviewer and participant in the research setting of these hotels, I also adopted and tried to realize the persona of an emancipated woman traveler, managing social media representation of her identity in the emancipating context. This is apparent in

Figure 4, where I curate the impression of being free and a foreign visitor to the Banyan Tree House at Lux Grand Gaube, when in fact, I am Mauritian by birth.

Online research was also conducted on the Bel Ombre Heritage Resorts and primary data collection at the Chateau de Bel Ombre (See

Figure 5) near the PDS of Villas Valriche. To encounter the narrative of this space required viewing the many promotional videos of the sites; two are selected for analysis in this paper.

Similar to the lifestyle “turn” at the Lux Collective, the narrative of Villas Valriche and Chateau de Bel Ombre in the Belle Riviere District of Mauritius is embedded in a story of the heritage of the region, its intertwined colonial and local community culture, and the presence of nature (and the grounded-ness that this offers) in the lives of future inhabitants and visitors. In the first video, one encounters Bel Ombre, a region with an industrial sugar plantation history. The video chosen for Bel Ombre [

53] foregrounds the natural heritage vision and endeavor of the Bel Ombre Heritage Resorts. The video is followed by a series of other clips which emphasize the sustainable development journey of the group. The main video emphasizes the unity of sea, land, and life (

la mer, la terre, la vie). The emphasis is on creating space for and sustaining natural heritage and the symbiosis of humans with nature.

At Bel Ombre Heritage Resorts (and specifically in relation to the Chateau), there is a leveraging of the plantation history as an important source of historical identity. The online promotional videos showcase the formal colonial gardens leading up to the chateau and the role of the historical owner, Telfair, in creating the chateau and its grounds. The videos in the series regarding the chateau and the Bel Ombre location indicate the area’s rich natural heritage at the heart of indigenous forests, rivers, and waterfalls. Not far away is the Domaine de Belle Rivières, crisscrossed by multiple streams and rivers important to the livelihood of local villagers. The property also borders on a nature reserve, declared a Man and Biosphere Reserve by UNESCO in 1977.

Originally focused on the cultivation of coffee, cotton, and indigo, the estate is now residential. Each villa in the PDS includes natural materials and local architectural features to maximize natural ventilation and light. The estate pays homage to an early tangible cultural heritage. Coupled with this visible, palpable history of the region is a masculinized cultural heritage in the form of hunting (and golfing) and wine and rum tasting. In contrast, perhaps then, to the Lux Collective, at the Chateau de Bel Ombre and the Telfair Golf course, there is a possibility for the temporary realization of a hegemonic masculinized self. The videos watched, however, do not reveal only this. They suggest that there is an effort to engage the local community and village of Bel Ombre itself in various environmentally conscious endeavors and sustainable development projects. One of the videos highlights the success of a local inhabitant who became the head sommelier of the chateau. The Creole man describes his journey from apprenticeship to his current position and what he was doing to help others needing assistance in the village.

4.2. Primary Data Findings

During in situ research, it was found that social production and cultural heritage signposting were evident in curated spaces across the grounds of Lux Grand Gaube and the Chateau de Bel Ombre. In the former, there is a nostalgic vending station for ice cream, the kind that one would find on the public beaches of Mauritius. There is also a rum house draped in the vines of a banyan tree, signaling the Creole heritage of the island and, visually, the rootedness of that heritage. Finally, there is the wine-tasting cellar which evokes the French heritage of the island (given the degustation of French and South African wines from Franschhoek in the cellar), and a nearby restaurant that evokes the hunting heritage of the French descendants. At the restaurant, one can order game meat dishes (i.e., roast deer meat) that harken back to the French colonial history of Mauritius. At the hotel then, it was found that established heritage narratives of ethnic history and associated productions (game meat, rum, fine wine) are compartmentalized for the tourist experience. Liberated women tourists can participate in such narratives, surfacing diverse forms of feminist empowerment in each locale.

The analysis partly aligns with a review of the online Annual Report of the Lux Collective [

40]. The report seeks to capture and identify diverse forms of social complexity emerging in the tourism collective. There is careful identification of the audience, purpose, values, and tagline of each of the Lux hotels and affiliated tourism establishments. The list indicates that for the Lux Collective, the audience can be objectively framed as “simplicity seekers” and “social capital seekers”, whereas those at SALT (such as the SALT of Palmar establishment) are “cultural purists” and “ethical travelers”. Lux helps people “celebrate life”, while SALT helps its clientele to “connect with local people and places”. Observation in situ, however, suggests that such narratives may be difficult to achieve. There are many kinds of visitors to these hotels, and there is divergent uptake of offerings for lifestyle improvement.

In the next section, the observation findings and the interview findings are offered. The discussion is closed with a summary overview and conclusion.

4.3. The Observation and Interview Results

The Lux Collective has several hotels in Mauritius, two of which were selected for primary data collection. The two hotels are Lux Grand Gaube in the northeastern part of the island and Lux Grand Baie in the north of the island. A third hotel was selected for observation and an interview, SALT of Palmar, which is also on the east coast of Mauritius. Lux Grand Gaube was opened in March 2018, and Lux Grand Bay in November 2021. SALT of Palmar was opened in November 2018. Lux Grand Gaube has 186 rooms, which are divided into six types, including villas and Prestige rooms, whereas Lux Grand Baie can accommodate guests in 86 suites, 8 villas, 20 residences, and 2 penthouses. SALT of Palmar is a smaller establishment with 59 sea-facing rooms. At the Lux Collective, the emphasis is on creating and offering a diversity of spaces in which one can experience an aspect of the island’s “identity”. There is a clear distinction between the hotels, as Lux Grand Gaube is classified as a five-star hotel and Lux Grand Baie as a five-star-plus hotel, meaning that it has more exclusive offerings and décor finishes, appealing to a clientele that is wealthier than those able to afford a five-star establishment. This is especially apparent at Lux Grand Gaube, where a retro-chic ethos plays on 1970s nostalgia and aesthetics. This ethos is represented in the videos discussed above.

Observations of the site were performed almost continuously for the two-week period of the research. As noted from the online assessments, it was clear that the Lux Collective strategically creates sensory and experiential spaces in which women seek freedom from the strictures of an imposed patriarchal (and perceived anti-environmentalist) ethos. This is first made possible by conscious suggestion in the promotional videos and is subsequently realized in the various activities and heritage spaces that women can enjoy on the hotel grounds, the “bubble” wherein they may feel free to express diverse identities.

An effort is made so that the tourist’s attention is not detracted from the crafted spaces. The employees wear only white (perhaps, to give visual effect to the adage of “lighter, brighter”) and move efficaciously from one set of tasks (attending to tables and room cleaning) to another. The resort is set so that tourists can have “complete” diversity within the grounds of the resort. There is enough to eat and “do” for a weekly package on the hotel grounds. In a way, this seems to mirror earlier tourism scholarship on the role of hotels providing an “environmental bubble” for the tourist, a cocoon, as the designer of the Lux Collective notes, for the tourist. To refine that earlier argument, one can say that the “environmental bubble” view ad even materialist feminism cannot really account for this situation; instead, it can be argued that a major desire/need of the woman tourist is the need for care and cocooning, for refuge from the violent intrusions and demands of a hegemonically masculine world.

The “heritage” activities are cultural (i.e., the wine tasting at the bespoke underground cellar, the ice-cream eating at the vendor under the palm trees, a drink of rum under the Banyan trees, or learning how to do Ashtanga yoga in the afternoon). It was observed that there was a strong environmental conservation ethos, even though everyone was aware that tourists arriving at the resort would have contributed to the global carbon footprint only by traveling to Mauritius. Food is not wasted at the Collective; it is “collected” and redistributed to the less fortunate. There were no disposable containers that one could see, and tourists were encouraged to reuse linen and towels to reduce water wastage. More substantively, interviewing one of the managers of the Lux Grand Gaube, it was learned that the resort works closely with marine biologists at an environmental NGO called Eco-Sud, to gauge and seek to protect marine biodiversity in the lagoon.

At SALT of Palmar, one observes even another level of environmental conservation and pursuit of sustainability. SALT of Palmar is noted to be for “cultural purists” and those committed to the principles of degrowth and “locavorism”, that is, the reduction in one’s ecological footprint via a choice of locally sourced foods and materials. One might say that SALT seeks to demonstrate the effect of systemic change for sustainability, as there is little tolerance for environmental impact. There are no televisions in SALT’s hotel rooms. Most of the products in each room are made from natural fibers and materials. Interviewing the manager of SALT, it was learned that the hotel represents and supports tangible and intangible cultural heritage by nominating “saltshakers”, local inhabitants with unique craft, music, and food-making skills to share with a global audience. Tourists at SALT are encouraged to ride a bicycle into the village to palpably encounter the sights, smells, tastes, and intangible cultural heritage of village life. These skills and experiences, as Khalil and Kozmal [

25] argue, allow tourists to pursue creativity and visceral experience at the tourist destination. The process is mediated by group engagement to facilitate socially transformative action. The manager of SALT also expressed the view that the approach is enabled by the socially inclusive landscape of the hotel. The lagoon in front of the hotel is still visited by local small-scale fishers. He said, “They are part of the landscape”.

At the five-star plus Lux Grand Baie, observations and two interviews were conducted at the exclusive spa. In this context, luxury products and bespoke experiences are used to distinguish additional forms of feminism and globalized heritages. For example, the spa manager explained that an important concern is the achievement of psychosocial and physiological balance in their, mainly women, patrons. Women arriving at the spa are often in search of respite from the demands of modern existence and the imbalances that such an existence brings. The spa therapists analyze, via a recognized survey, the dietary behaviors and inclinations of the women, propose new habit options and choices, and present a bespoke treatment plan that hopes to endear them to a better, more balanced existence. Organic products, locally or regionally sourced, are offered, as well as treatments utilizing natural products, such as salt, honey, ylang-ylang, and vanilla. Crowning these treatments are the manicures and pedicures offered by a globally renowned pedicurist–podiatrist who seeks to enhance the natural beauty of nailbeds by not covering these with lacquer. Thus, women exit their manicures with no experience of water (water softens the feet too much) and with no nail varnish, or at most, a varnish that is friendlier to the environment. While the woman seeking heritage experiences at Lux Grand Gaube may seek to visit the heritage sites curated by the hotel to help her engage with a simulation of local culture, at the Lux Grand Baie, heritage experiences are available indoors in the products used by the spa, the foods and drinks offered, and philosophies of self-care, beauty, and well-being, which are also informed, for example, by Ayurveda, historical, cultural philosophies of human health. This in situ study at Lux Grand Baie, the five-star plus establishment, indicates distinctions and hierarchies in access to and management of cultural heritage in tourism settings. Tourists with greater disposable wealth appear to have the option of not being encouraged to mingle with the local communities but to experience the locals in a body-distant and class-segregated manner. It is recognizing what Harradan [

54] describes as liberal feminism since it asserts the option of choice and possibility of disengagement rather than embedding interlocutors in the context.

At the Chateau de Bel Ombre, a process of partial embedding was apparent. Although the site is one of rich cultural history and social exchange, this was not clearly apparent to me as the researcher. Remnants of the industrial and slave heritage of the establishment were apparent in the partial conservation of the nearby sugar factory, which, according to an interviewee from the village, had been the center of social and economic life many years ago. Interviewing the CEO, two sommeliers, and two inhabitants in the area, it was found that the Chateau had become the centerpiece of the property development scheme (PDS) and Telfair golf course. The Chateau, expressive of the tangible cultural heritage of Mauritius, did not feature as a heritage site, and its complex social history was only documented in the promotional videos set for international homebuyers and investors. Part of the challenge is that the Chateau is used as a restaurant establishment and, perhaps, therefore, does not come under the aegis of government-managed cultural heritage sites.

Considering the role of gender in such spaces or other potential intersubjectivities at play in the space, it is found that the site expresses a mainly hegemonic, masculine ethos. The place is mainly known for its golf course, and international male players come to the site to play golf. It was learned that only in recent years that the local gardeners have allowed indigenous fauna and flora to return to the landscape, thereby creating a more authentic natural heritage space for international visitors to encounter. In the broader context of the Chateau and the village of Bel Ombre, a rich cultural heritage and history could be better integrated into the public narrative of the estate, and local communities could be more visible in the cultural expression and reminisce of the area. The sommeliers indicated that they tried to bring in local tastes of wine and locally crafted drinks to diversify the still mainly French menu. They had succeeded in doing so several times, as tourists desire culturally influenced meals that are, at the very least, palatable. The one sommelier added that recognizing these tourist needs required self-reflexivity and attention to one’s own cultural diversity. Using a wine metaphor, he alluded to himself as a “pinot noir—white on the outside and black on the inside”, indicating that such diversity and openness to diversity had allowed him to cross various cultural divides. The other sommelier conceded but added that cultural and racial integration was still an arduous process in Mauritius and that it may be important to demonstrate shared histories and identities more clearly, for a more genuine representation of history and heritage.

Observations beyond these tourism establishment sites reveal a hugely diverse and overlapping cultural heritage landscape. Mauritius has a vibrant street food scene; the cultural values and practices of the people are evident in publicly demonstrated ritual practices, such as the Tamil ritual of Cavadee or the 40-heures (40-h) ritual visitation of Catholic churches during the Lenten period. Such ritual activities are accompanied by a plethora of ICH, from food consumption to appropriate dress for the occasion and/or appropriated social behavior. In brief, and given the scope of this article, it is fair to argue that much of cultural heritage management continues beyond formal heritage management processes in Mauritius. Presently, tourism establishments are perceived as sources of foreign direct investment. They are not understood or perceived as spaces of cultural production. However, as this study has shown, there is ample evidence via secondary sources (i.e., annual reports and promotional videos) that the managers and corporate teams of these establishments are active in heritage management and may have valuable insight to conveying to formal heritage managers on the role of play, activism, and gendered liberation in heritage conservation.