Antecedents of Consumers’ Intention and Behavior to Purchase Organic Food in the Portuguese Context

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Organic Food

2.2. Theory of Planned Behavior

2.3. Environmental Concern

2.4. Health Consciousness

2.5. Attitude, Purchase Intention and Purchase Behavior

3. Materials and Methods

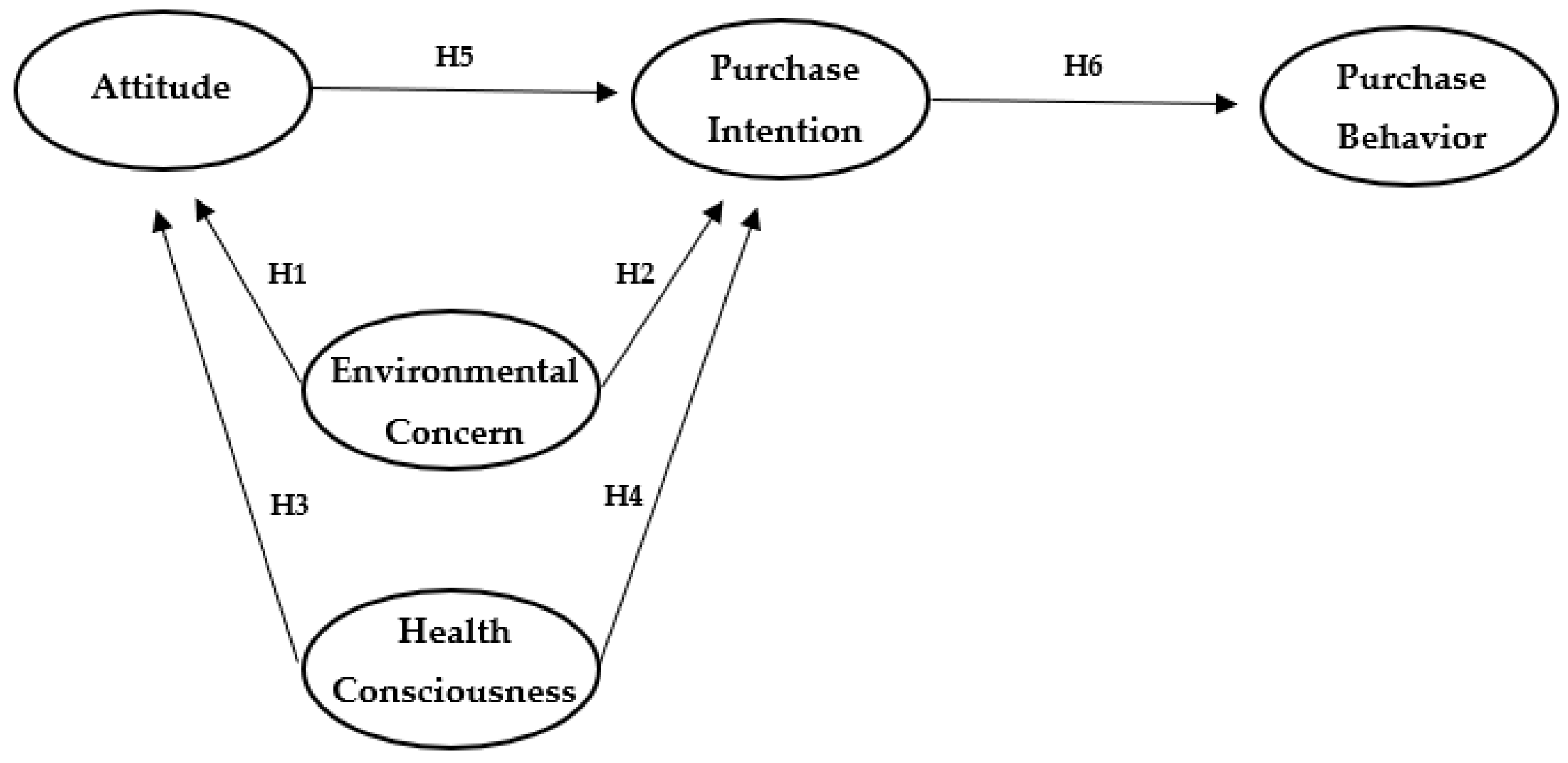

3.1. Research Framework

3.2. Questionnaire Design

3.3. Data Collection and Sample Composition

3.4. Statistical Analysis

4. Results

4.1. Measurement Model: Reliability and Validity

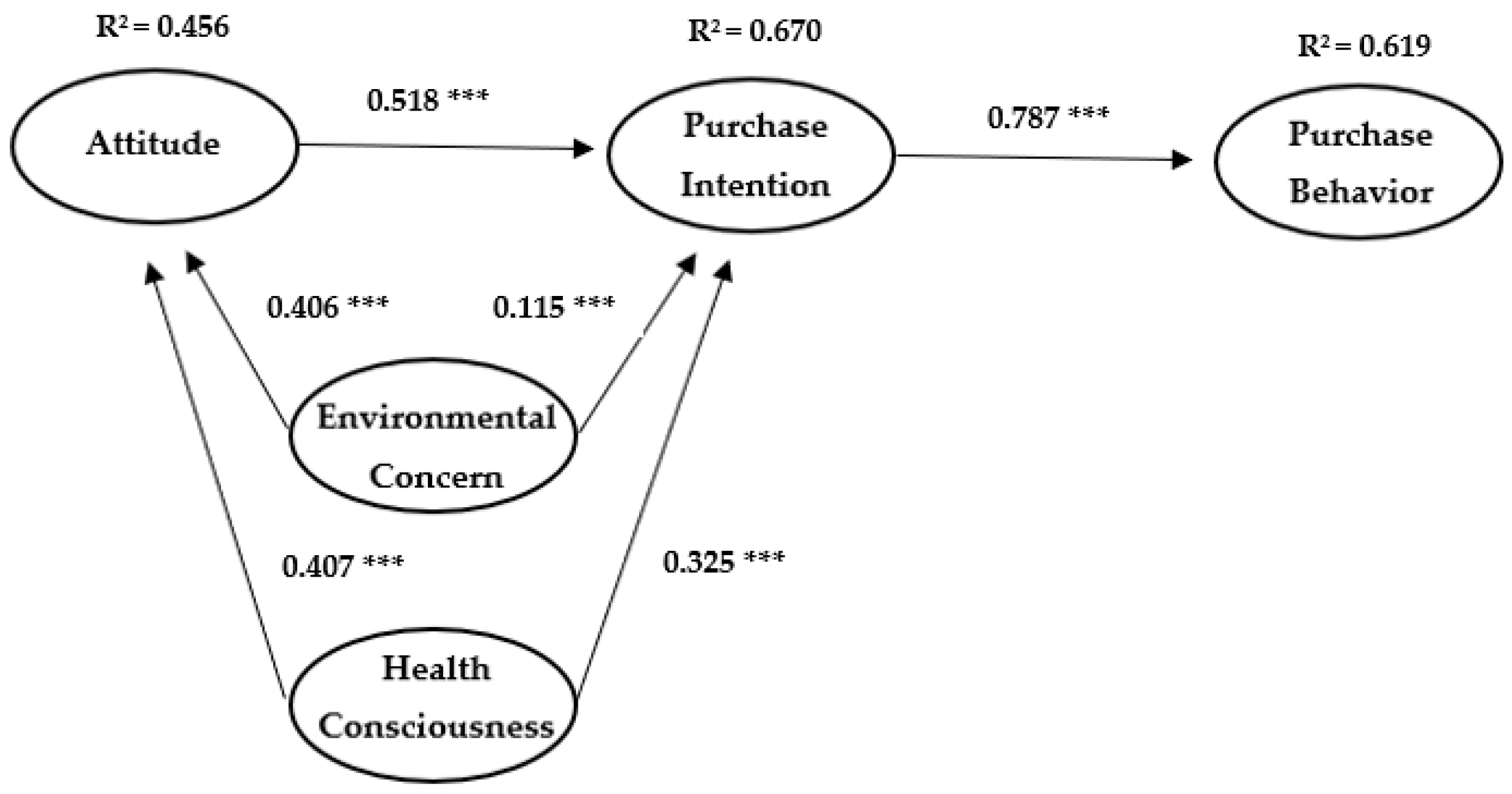

4.2. Structural Model: Hypothesis Testing

5. Discussion and Implications

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Correction Statement

References

- Eid, R.; Agag, G.; Shehawy, Y.M. Understanding Guests’ Intention to Visit Green Hotels. J. Hosp. Tour. Res. 2021, 45, 494–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Doorn, J.; Verhoef, P.C. Drivers of and Barriers to Organic Purchase Behavior. J. Retail. 2015, 91, 436–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryła, P. Organic food consumption in Poland: Motives and barriers. Appetite 2016, 105, 737–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jaiswal, D.; Kant, R. Green purchasing behaviour: A conceptual framework and empirical investigation of Indian consumers. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2018, 41, 60–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finch, J.E. The impact of personal consumption values and beliefs on organic food purchase behavior. J. Food Prod. Mark. 2006, 11, 63–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prakash, G.; Singh, P.K.; Yadav, R. Application of consumer style inventory (CSI) to predict young Indian consumer’s intention to purchase organic food products. Food Qual. Prefer. 2018, 68, 90–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liobikienė, G.; Bernatonienė, J. Why determinants of green purchase cannot be treated equally? The case of green cosmetics: Literature review. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 162, 109–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koklic, M.K.; Golob, U.; Podnar, K.; Zabkar, V. The interplay of past consumption, attitudes and personal norms in organic food buying. Appetite 2019, 137, 27–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nafees, L.; Hyatt, E.M.; Garber, L.L., Jr.; Das, N. Exploration of the organic food-related consumer behavior in emerging and developed economies: The case of India and the US. Int. J. Manag. Pract. 2020, 13, 604–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janssen, M. Determinants of organic food purchases: Evidence from household panel data. Food Qual. Prefer. 2018, 68, 19–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chekima, B.; Chekima, K.; Chekima, K. Understanding factors underlying actual consumption of organic food: The moderating effect of future orientation. Food Qual. Prefer. 2019, 74, 49–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yazdanpanah, M.; Forouzani, M. Application of the Theory of Planned Behaviour to predict Iranian students’ intention to purchase organic food. J. Clean. Prod. 2015, 107, 342–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, R.; Pathak, G.S. Intention to purchase organic food among young consumers: Evidences from a developing nation. Appetite 2016, 96, 122–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Asif, M.; Xuhui, W.; Nasiri, A.; Ayyub, S. Determinant factors influencing organic food purchase intention and the moderating role of awareness: A comparative analysis. Food Qual. Prefer. 2018, 63, 144–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rana, J.; Paul, J. Consumer behavior and purchase intention for organic food: A review and research agenda. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2017, 38, 157–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kushwah, S.; Dhir, A.; Sagar, M. Understanding consumer resistance to the consumption of organic food. A study of ethical consumption, purchasing, and choice behaviour. Food Qual. Prefer. 2019, 77, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pham, T.H.; Nguyen, T.N.; Phan, T.T.H.; Nguyen, N.T. Evaluating the purchase behaviour of organic food by young consumers in an emerging market economy. J. Strateg. Mark. 2019, 27, 540–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radzyminska, M.; Jakubowska, D. The conceptualization of novel organic food products: A case study of Polish young consumers. Br. Food J. 2019, 121, 1884–1898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, S.Y.; Chang, C.C.; Lin, T.T. Safety, sustainability, and consumers’ perceived value in affecting purchase intentions toward organic food. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE International Conference on Industrial Engineering and Engineering Management, Singapore, 10–13 December 2017; pp. 2312–2316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghali-Zinoubi, Z.; Toukabri, M. The antecedents of the consumer purchase intention: Sensitivity to price and involvement in organic product: Moderating role of product regional identity. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2019, 90, 175–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wee, C.S.; Ariff, M.S.B.M.; Zakuan, N.; Tajudin, M.N.M.; Ismail, K.; Ishak, N. Consumers perception, purchase intention and actual purchase behavior of organic food products. Rev. Integr. Bus. Econ. Res. 2014, 3, 378. [Google Scholar]

- do Paço, A.; Shiel, C.; Alves, H. A new model for testing green consumer behaviour. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 207, 998–1006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, J.; Modi, A.; Patel, J. Predicting green product consumption using theory of planned behavior and reasoned action. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2016, 29, 123–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fishbein, M.; Ajzen, I. Belief, Attitude, Intention, and Behavior: An Introduction to Theory and Research; Addison-Wesley: Reading, MA, USA, 1975; Available online: https://people.umass.edu/aizen/f&a1975.html (accessed on 28 May 2023).

- Ajzen, I. The theory of planned behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1991, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çabuk, S.; Tanrikulu, C.; Gelibolu, L. Understanding organic food consumption: Attitude as a mediator. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2014, 38, 337–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thøgersen, J.; Barcellos, M.D.; Perin, M.G.; Zhou, Y. Consumer buying motives and attitudes towards organic food in two emerging markets: China and Brazil. Int. Mark. Rev. 2015, 32, 389–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nafees, L.; Hyatt, E.M.; Garber, L.L., Jr.; Das, N.; Boya, U.O. Motivations to buy organic food in emerging markets: An exploratory study of urban Indian millennials. Food Qual. Prefer. 2022, 96, 104375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, R.; Pathak, G.S. Determinants of Consumers’ Green Purchase Behavior in a Developing Nation: Applying and Extending the Theory of Planned Behavior. Ecol. Econ. 2017, 134, 114–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, J.A.; Bacon, D.R. Exploring the Subtle Relationships between Environmental Concern and Ecologically Conscious Consumer Behavior. J. Bus. Res. 1997, 40, 79–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarkiainen, A.; Sundqvist, S. Subjective Norms, Attitudes and Intentions of Finnish Consumers in Buying Organic Food. Br. Food J. 2005, 107, 808–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Wiegerinck, V.J.J.; Krikke, H.R.; Zhang, H. Understanding the purchase intention towards remanufactured product in closed-loop supply chains: An empirical study in China. Int. J. Phys. Distrib. Logist. Manag. 2013, 43, 866–888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michaelidou, N.; Hassan, L. The role of health consciousness, food safety concern and ethical identity on attitudes and intentions towards organic food. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2008, 32, 163–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, C.; Cheung, R.; Shen, G.Q. Recycling attitude and behaviour in university campus: A case study in Hong Kong. Facilities 2012, 30, 630–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malhotra, N.K.; Nunan, D.; Birks, D.F. Marketing Research: An Applied Approach, 7th ed.; Pearson: Harlow, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiss, A.M.; Heide, J.B. The nature of organizational search in high technology markets. J. Mark. Res. 1993, 30, 220–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clow, K.E.; James, K.E. Essentials of Marketing Research: Putting Research into Practice, 1st ed.; SAGE: New York, NY, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.F.; Black, W.C.B.; Babin, B.J.; Anderson, R.E. Multivariate Data Analysis, 7th ed.; Pearson: New York, NY, USA, 2014; Available online: https://www.scirp.org/(S(czeh2tfqyw2orz553k1w0r45))/reference/referencespapers.aspx?referenceid=2190475 (accessed on 28 May 2023).

- Lee, H.J.; Yun, Z.S. Consumers’ perceptions of organic food attributes and cognitive and affective attitudes as determinants of their purchase intentions toward organic food. Food Qual. Prefer. 2015, 39, 259–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schreiber, J.B.; Stage, F.K.; King, J.; Nora, A.; Barlow, E.A. Reporting structural equation modeling and confirmatory factor analysis results: A review. J. Educ. Res. 2006, 99, 323–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, L.T.; Bentler, P.M. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct. Equ. Model. 1999, 6, 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagozzi, R.P.; Yi, Y. On the evaluation of structural equation models. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 1988, 16, 74–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falk, R.F.; Miller, N.B. A Primer for Soft Modelling; University of Akron Press: Akron, OH, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

| Author(s) | Definition | Keyword |

|---|---|---|

| [15] | “Organic food encompasses natural food items free of artificial chemicals such as fertilizers, herbicides, pesticides, antibiotics and genetically modified organisms” (p. 158). | Natural |

| [2] | “Food products that are safe for consumption, of good quality, nutritious and produced under the principle of sustainable development” (p. 1884). | Safe; Quality; Nutritious; Healthy; Sustainable Development |

| [18] | “Food grown using renewable resources and conserving soil and water to improve environmental quality for future generations, (...) is not grown or processed with conventional pesticides, synthetic fertilizers, bioengineering or ionizing radiation” (p. 259). | Quality; Future generations |

| [17] | “Product obtained or manufactured according to the standards of organic agriculture that sustain and promote the well-being of soils, ecosystems and human beings” (p. 540). | Well-being; Organic agriculture |

| Variables | Measuring Items | Sources of Adoption |

|---|---|---|

| Environmental Concern |

| [13], adapted from [30]. |

| Health Consciousness |

| [6,13,17], adapted from [31]. |

| Attitude |

| [13], adapted from [32]. |

| Purchase Intention |

| [17], adapted from [33] and [13]. |

| Purchase Behavior |

| [29], adapted from [34]. |

| Variables | Measurement Items | FL * | FL ** | α |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Environmental Concern (EC) | EC1 | 0.641 | 0.642 | 0.782 |

| EC2 | 0.824 | 0.824 | ||

| EC3 | 0.728 | 0.727 | ||

| EC4 | 0.639 | 0.639 | ||

| Health Consciousness (HC) | HC1 | 0.721 | 0.709 | 0.696 |

| HC2 | 0.515 | - | ||

| HC3 | 0.741 | 0.752 | ||

| Attitude (A) | A1 | 0.866 | 0.866 | 0.925 |

| A2 | 0.896 | 0.896 | ||

| A3 | 0.915 | 0.915 | ||

| A4 | 0.808 | 0.808 | ||

| Purchase Intention (PI) | PI1 | 0.876 | 0.876 | 0.924 |

| PI2 | 0.952 | 0.952 | ||

| PI3 | 0.877 | 0.876 | ||

| Purchase Behavior (PB) | PB1 | 0.953 | 0.949 | 0.920 |

| PB2 | 0.944 | 0.949 | ||

| PB3 | 0.484 | - |

| CR | AVE | MSV | MaxR(H) | HC | A | PI | PB | EC | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HC | 0.696 | 0.534 | 0.430 | 0.698 | 0.731 | ||||

| A | 0.907 | 0.764 | 0.376 | 0.917 | 0.560 | 0.874 | |||

| PI | 0.929 | 0.814 | 0.610 | 0.942 | 0.656 | 0.762 | 0.902 | ||

| PB | 0.948 | 0.901 | 0.610 | 0.948 | 0.550 | 0.613 | 0.781 | 0.949 | |

| EC | 0.803 | 0.507 | 0.314 | 0.822 | 0.378 | 0.560 | 0.528 | 0.396 | 0.712 |

| X2 | DF | X2/DF | RMSEA | NFI | CFI | TLI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reference 1 | - | - | ≤3 | <0.08 | ≥0.90 | ≥0.90 | ≥0.90 |

| Results | 169.927 | 80 | 2.124 | 0.061 | 0.947 | 0.971 | 0.956 |

| Hypothesis | Hypothesized Path | β | S.E. | t-Value | p-Value | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H1 | EC → A | 0.406 | 0.125 | 5.906 | *** | Supported |

| H2 | EC → PI | 0.115 | 0.094 | 2.073 | 0.038 | Supported |

| H3 | HC → A | 0.407 | 0.107 | 5.576 | *** | Supported |

| H4 | HC → PI | 0.325 | 0.091 | 4.861 | *** | Supported |

| H5 | A → PI | 0.518 | 0.061 | 7.936 | *** | Supported |

| H6 | PI → PB | 0.787 | 0.064 | 14.357 | *** | Supported |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ferreira, S.; Pereira, O. Antecedents of Consumers’ Intention and Behavior to Purchase Organic Food in the Portuguese Context. Sustainability 2023, 15, 9670. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15129670

Ferreira S, Pereira O. Antecedents of Consumers’ Intention and Behavior to Purchase Organic Food in the Portuguese Context. Sustainability. 2023; 15(12):9670. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15129670

Chicago/Turabian StyleFerreira, Sandra, and Olga Pereira. 2023. "Antecedents of Consumers’ Intention and Behavior to Purchase Organic Food in the Portuguese Context" Sustainability 15, no. 12: 9670. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15129670

APA StyleFerreira, S., & Pereira, O. (2023). Antecedents of Consumers’ Intention and Behavior to Purchase Organic Food in the Portuguese Context. Sustainability, 15(12), 9670. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15129670