Disposable Diaper Usage and Disposal Practices in Samora Machel Township, South Africa

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Study Area

1.2. Theoretical Approach

- A systemic worldview requires that systems are observed as a whole with all their elements connected and in interaction with each other. Relevant to this study, Virapongse et al. [25] argued that to build a systemic worldview of the issue at hand, we must understand the system, which can only be achieved via engagement with all stakeholders using platforms such as focus groups, interviews, and workshops.

- Transdisciplinary approaches enable the codevelopment of new and rich knowledge and processes when a diverse group of experts and stakeholders is involved. Transdisciplinarity has the potential to create multiple perspectives and possible solutions relative to complex environmental problems.

- Codevelopment of knowledge implies that researchers should move away from being experts to be “one of the many actors within a system that contributes to the learning and knowledge generation process” [25].

- Virapongse et al. [25] emphasized that SESs should be built on appropriate, solid data collection, monitoring systems and management between all parties involved. This includes data collection by researchers and the use of citizen science and participatory research practices with community members.

- Education, training, and capacity building are integral parts and continuous processes of the SES process for all involved. They include using systems thinking and SES approaches in the management of environmental issues and embracing the knowledge, belief systems, and practices of all stakeholders.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Research Phases

2.1.1. Phase 1—Quantitative Study: Questionnaire

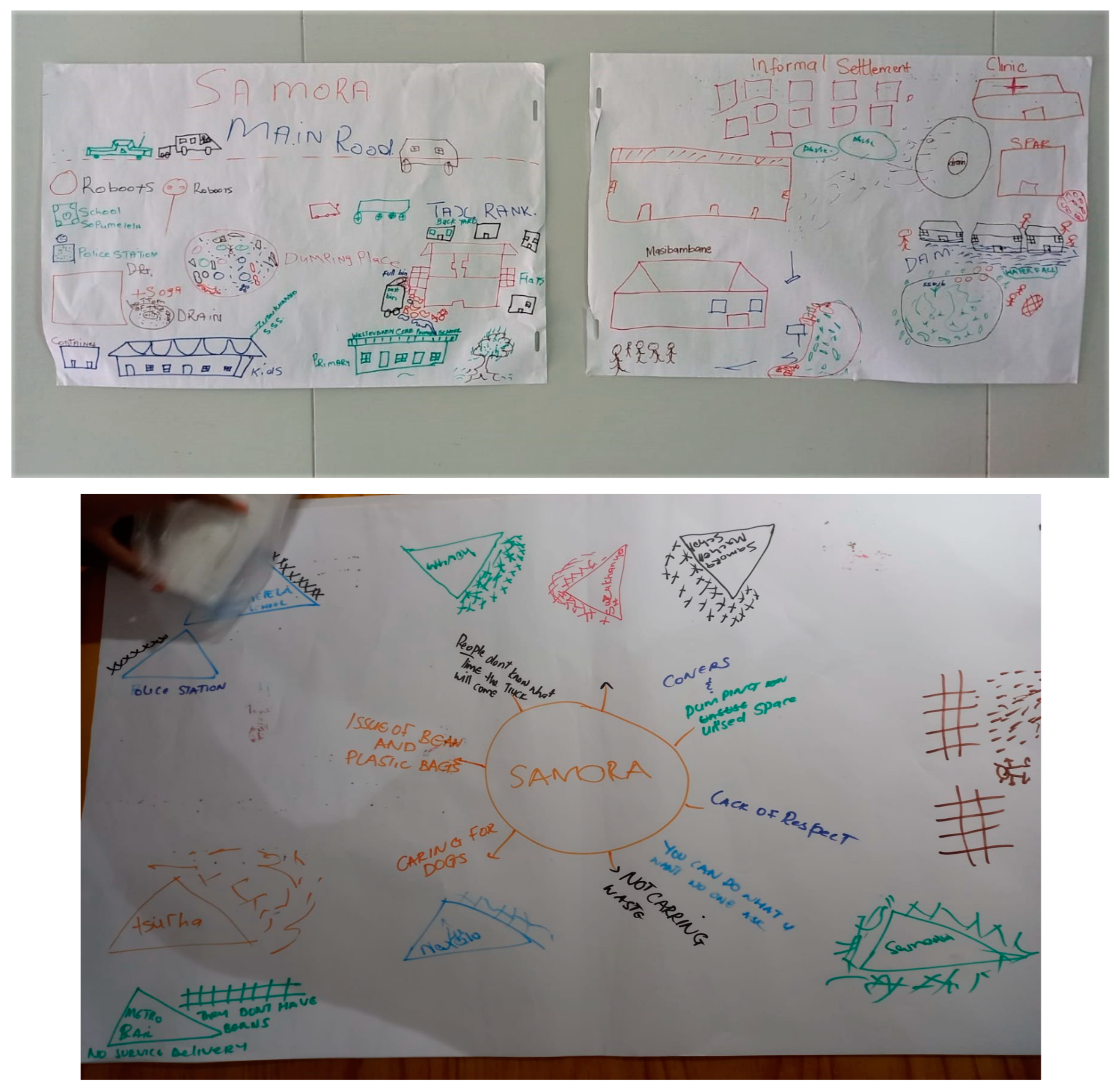

2.1.2. Phase 2: Qualitative Phase

- The questionnaires used in Phase 1 contained a few explanatory qualitative questions, which provided valuable explanatory data.

- In addition, two focus group discussions were facilitated: the first on 13 September 2022 at the Masibambane Community Centre (Figure 4) and the second on 1 October 2022 at Sondela B&B in Samora Machel. The focus group discussions were held on Saturdays to create opportunities for both working and nonworking mothers to participate.

3. Results

3.1. Quantitative Results

3.1.1. Biographical Data of Participants

3.1.2. Social Security Grants

3.1.3. Diaper Use and Disposal Practices

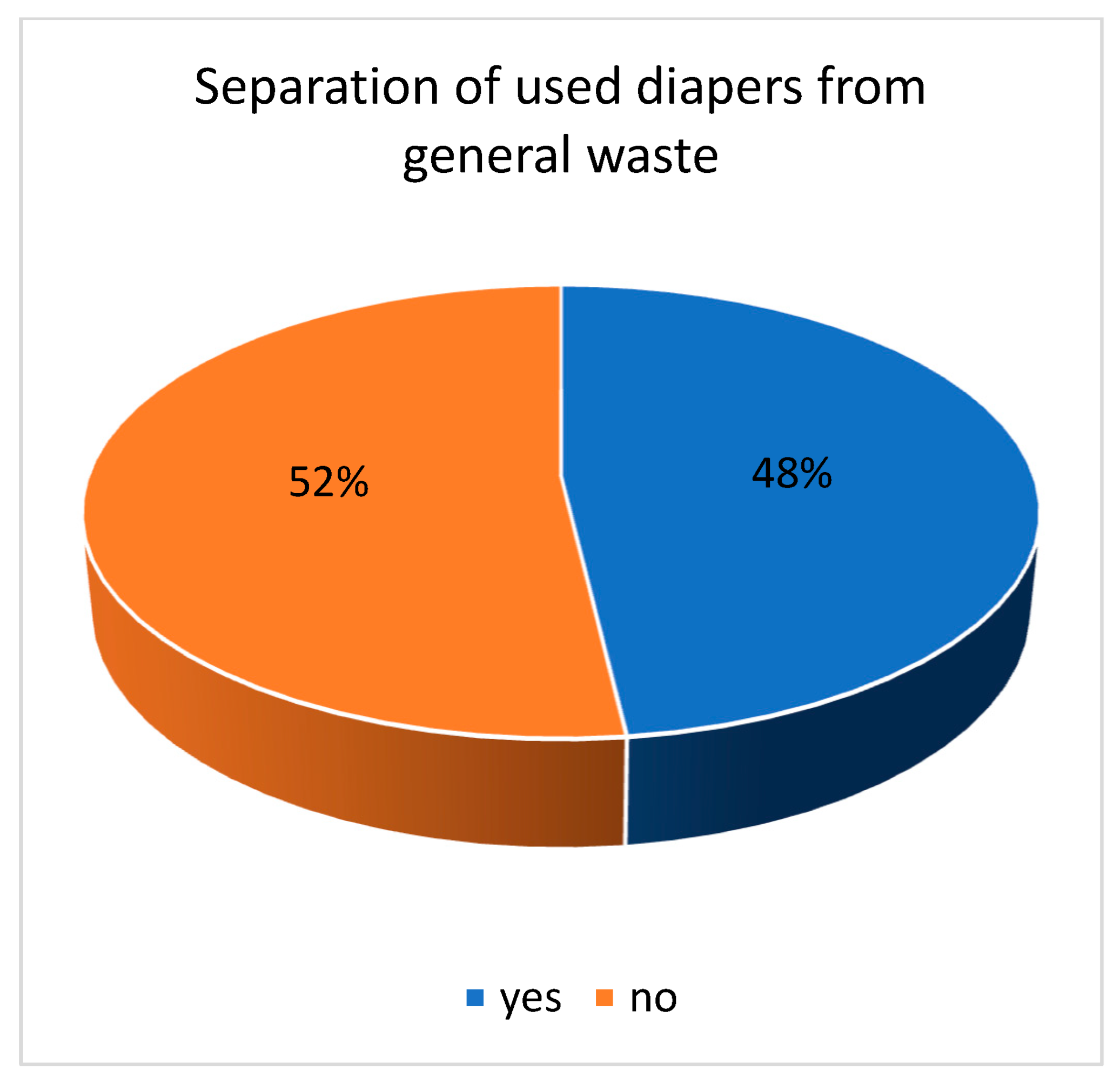

3.1.4. Willingness to Separate Diapers from General Waste

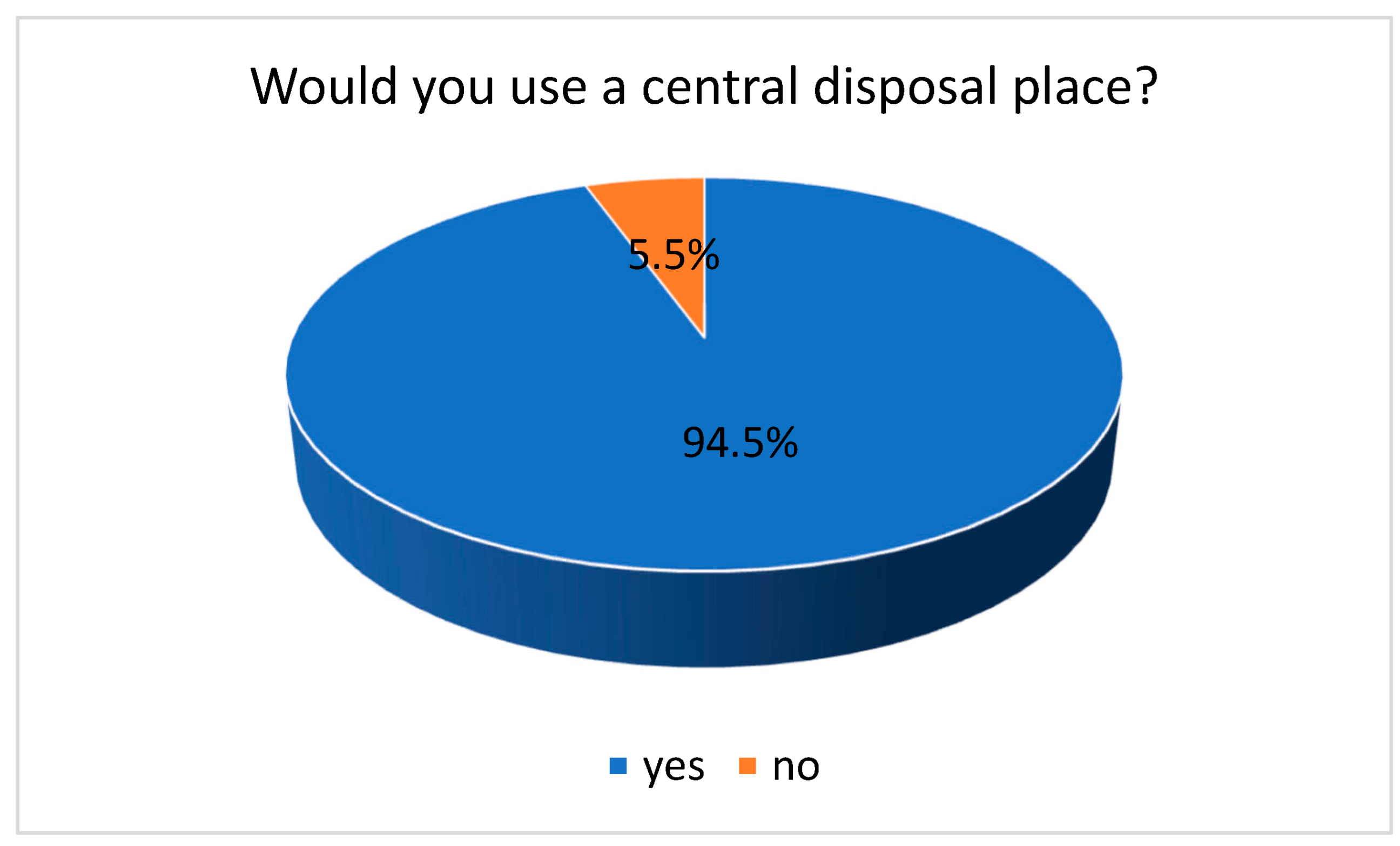

3.1.5. Taking Diapers to a Central Place

3.1.6. Buying Patterns and Preferences Regarding Disposable Diapers

3.2. Qualitative Results

- Theme 1: Reasons for preferring disposable diapers;

- Theme 2: Perceptions about the impact of disposable diapers on people and the environment;

- Theme 3: Hindrances to waste and diaper management in Samora Machel township.

3.2.1. Theme 1: Reasons for Preferring Disposable Diapers

3.2.2. Theme 2: Perceptions about the Impact of Disposable Diapers on People and the Environment

3.2.3. Theme 3: Hindrances to Waste and Diaper Management in Samora Machel Township

4. Discussion and Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Płotka-Wasylka, J.; Makoś-Chełstowska, P.; Kurowska-Susdorf, A.; Treviño, M.J.S.; Guzmán, S.Z.; Mostafa, H.; Cordella, M. End-of-life management of single-use baby diapers: Analysis of technical, health and environment aspects. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 836, 155339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kordecki, H.; Antrobus-Wuth, R.; Uys, M.T.; Van Wyk, I.; Root, E.D.; Berrian, A.M. Disposable diaper waste accumulation at the human-livestock-wildlife interface: A one health approach. Environ. Chall. 2022, 8, 100589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP). Single-Use Diapers and Their Alternatives: Recommendations from Life Cycle Assessments; United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP): Nairobi, Kenya, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Department of Fisheries, Forestry and the Environment (DFFE). Detailed Feasibility Study and Business Case/s for the Establishment of Refuse Derived Fuel Plants to Address Absorbent Hygiene Products and other Residual Materials; Department of Fisheries, Forestry and the Environment (DFFE): Pretoria, South Africa, 2021.

- Schenck, C.J.; Nell, C.; Chitaka, T. Technical report: Exploring disposable diaper usage and disposal practices in rural areas. In Waste Research Development and Innovation Roadmap Report; CSIR: Pretoria, South Africa, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Cabrera, A.; Garcia, R. The Environmental & Economic Costs of Single-Use Menstrual Products, Baby Diapers & Wet Wipes: Investigating the Impact of These Single-Use Items across Europe. 2019. Available online: https://zerowasteeurope.eu/wp-content/uploads/2019/12/bffp_singleuse_menstrual_products_baby_diapers_and_wet_wipes.pdf (accessed on 3 February 2023).

- Ng, F.S.F.; Muthu, S.S.; Li, Y.; Hui, P.C. A Critical Review on Life Cycle Assessment Studies of Diapers. Crit. Rev. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2013, 43, 1795–1822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffmann, B.S.; De Simone Morais, J.; Teodoro, P.F. Life cycle assessment of innovative circular busineness models for modern cloth diapers. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 249, 119364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Statistics South Africa (Stats SA). General Household Survey Statistical Release PO 318. 2022. Available online: https://www.statssa.gov.za/publications/P0318/P03182021.pdf (accessed on 5 February 2023).

- Godfrey, G.; Ahmed, M.T.; Gebremedhin, K.G.; Katima, J.H.Y.; Oelofse, S.; Osibanjo, O.; Richter, U.H.; Yonli, A.H. Solid waste management in Africa: Governance failure or development opportunity? In Regional Development in Africa; Edomah, N., Ed.; Intech Open: London, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schenck, C.J.; Nell, C.; Grobler, L.; Blaauw, D. Technical Report Clean Cities/Towns Project. CSIR Waste Roadmap. 2022. Available online: https://wasteroadmap.co.za/wp-content/uploads/2022/04/19-UWC_Final-Report-Clean-Cities-Towns.pdf (accessed on 10 February 2023).

- Kalina, M.; Makweta, N.; Tilley, E. “The rich will always be able to dispose of their waste”: A view from the frontiers on municipality failures in Makhanda South Africa. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2023, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodseth, C.; Notten, P.; von Blottnitz, H. A revised approach for estimating informally disposed domestic waste in rural versus urban South Africa and implications for waste management. S. Afr. J. Sci. 2020, 116, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molefe, K. The Rise of Backyard Shacks and the Implication for Solid Waste Management Service Provision in Bram Fischerville. Master’s Dissertation, Department of Geography, University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, South Africa, 2016. Available online: https://wasteroadmap.co.za/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/1_Wits_2016_Molefe.pdf (accessed on 3 February 2023).

- Breuckner, J.K.; Rabe, C.; Sebot, H. Backyarding in South Africa. 2018. Available online: https://housingfinanceafrica.org/app/uploads/Brueckner-South-Africa-backyarding-1.pdf (accessed on 10 March 2023).

- Schenck, C.J.; Tyrrell, H.; Grobler, L.; Niyobuhungiro, R.; Chitaka, T.Y.; Nell, N. Managing Waste in Low Income Communities by Formalising Dumpsites: Lessons Learned from Drakenstein Municipality; Technical Report for IUCN/MARPLASTICS. 2021. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/355586461_Managing_waste_in_lower-income_communities_by_formalising_illegal_dump_sites_Learnings_from_Drakenstein_Municipality (accessed on 12 February 2023). [CrossRef]

- Itumeleng Youth Project. A Mountain of Disposable Diapers. 2018. Available online: https://www.emg.org.za (accessed on 12 February 2023).

- Sepadi, M.M. Unsafe management of soiled diapers in informal settlements and villages of South Africa. Cities Health 2021, 6, 254–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ntekpe, M.E.; Mbong, E.O.; Edem, E.N.; Hussain, S. Disposable diapers: Impact of disposal methods on public health and the environment. Am. J. Med. Public Health 2020, 1, 1009. [Google Scholar]

- Mkentane, O. Cape Town—Learning at Naluxolo Primary School in Samora Machel Has Been Disrupted Due to the Blockage of a Nearby Drain That Has Caused 15 Toilets to Spill. 2022. Available online: https://www.iol.co.za/capetimes/news/blocked-drains-disrupt-learning-in-samora-machel-as-toilets-spill-c73dd4cb-8575-47ce-bda6-d7d0b2e7bcd0 (accessed on 14 February 2023).

- Phaliso, S. Freedom Day in Philippi: Gunshots, Robberies and Piles of Rubbish. Mail and Guardian. 27 April 2023. Available online: https://mg.co.za/news/2023-04-27-freedom-day-in-philippi-gunshots-robberies-and-piles-of-rubbish/ (accessed on 15 May 2023).

- Matsobane, S.S.H. An Investigation of Practices and Effects of Disposable Infant Diapers on the Environment: A Case Study of Mashashane Village. Master’s Thesis, University of Limpopo, Polokwane, South Africa, 2021. Available online: http://ulspace.ul.ac.za/bitstream/handle/10386/3851/seopa_shm_2021.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y (accessed on 12 February 2023).

- Lloyd, P. The Energy Profile of a Low-Income Urban Community. In Proceedings of the 2014 International Conference on the Domestic Use of Energy (DUE), Cape Town, South Africa, 1–2 April 2014; Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/269303056_The_energy_profile_of_a_low-income_urban_community (accessed on 8 February 2023).

- Biggs, R.; Rhode, C.; Archibald, S.; Kunene, L.M.; Mutanga, S.S.; Nkuna, N.; Ocholla, P.O.; Phadima, L.J. Strategies for managing complex social-ecological systems in the face of uncertainty: Examples from South Africa and beyond. Ecol. Soc. 2015, 20, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Virapongse, A.; Brooks, S.; Covelli Metcalf, E.; Zedalis, M.; Gosz, J.; Kliskey, A.; Alessa, L. A social-ecological systems approach for environmental management. J. Environ. Manag. 2016, 178, 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colding, J.; Barthel, S. Exploring the social-ecological systems discourse 20 years later. Ecol. Soc. 2019, 24, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sammut-Bonnici, T. 2015 Complexity Theory. In Wiley Encyclopedia of Management; John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amauchi, J.F.F.; Gauthier, M.; Ghezeljeh, A.; Giatti, A.L.L.; Keats, K.; Sholanke, D.; Zachari, D.; Gutberlet, J. The power of community-based participatory research: Ethical and effective ways of researching. Community Dev. 2022, 53, 3–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duke, M. Community-based participatory research. Anthropology 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Statistics South Africa. 2022 Quarterly Labour Force Survey (QLFS 2:2022). 2022. Available online: https://www.statssa.gov.za/?p=15685 (accessed on 12 February 2023).

- Statistics South Africa. 2022 Quarterly Labour Force Survey (QLFS 3:2022). 2023. Available online: https://www.statssa.gov.za/publications/P0211/Presentation%20QLFS%20Q3%202022.pdf (accessed on 20 February 2023).

- Madisa, K.; Amashabala, M. Half of South Africa’s population are 100% dependent on state welfare. Sowetanlive. 6 January 2023. Available online: https://www.sowetanlive.co.za/news/south-africa/2023-01-06-half-of-south-africas-population-are-100-dependent-on-state-welfare/ (accessed on 15 February 2023).

- Kim, K.S.; Kim, K.J. Evaluation of a disposable diaper collection trial in Korea through comparison with and absorbent -hygiene product collection trial in Scotland. Sustainability 2018, 10, 773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grolleau, G.; Ibanez, L.; Mzoughi, N.; Teisl, M. Helping eco-labels to fulfil their promises. Clim. Policy 2016, 16, 792–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perez, M.V.; Navarro, P.X.S.; Morillas, A.V.; Espinosa Valdemar, R.M.; Lopez Araiza, J.P.H. Waste management and environmental impact of absorbent hygiene products: A review. Waste Manag. Res. 2021, 39, 767–783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tshangana, A. Local Government Position on Municipal Responses to Backyarders and Backyard Dwellings. South African Local Government Association. 2014. Available online: https://static.pmg.org.za/150606SALGA_policy.pdf (accessed on 20 February 2023).

- Salvia, G.; Zimmerman, N.; Willan, C.; Hale, J.; Gitau, H.; Muindi, K.; Gichana, E.; Davies, M. The wicked problem of waste management:An attention-based anasysis of stakeholder behaviours. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 326, 129200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Niyobuhungiro, R.V.; Schenck, C.J. A global literature review of the drivers of indiscriminate dumping of waste: Guiding future research in South Africa. Dev. South. Afr. 2022, 39, 321–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tembo, T. No Water and Sanitation Services for Samora Machel after City Official Shot. Cape Argus. 6 April 2021. Available online: https://www.iol.co.za/capeargus/news/no-water-and-sanitation-services-for-samora-machel-after-city-official-shot-420d7f69-f8af-4976-ae5b-820ed3fc005f (accessed on 12 February 2023).

- Jesca, M.; Junior, M. Practices Regarding Disposal of Soiled Diapers among Women of Child Bearing Age in Poor Resource Urban Setting. IOSR J. Nurs. Health Sci. 2015, 4, 63–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalina, M. As South Africa’s cities burn: We can clean up, but we cannot sweep away inequality. Local Environ. 2021, 26, 1186–1191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velis, C.A.; Wilson, D.C.; Gavish, Y.; Grimes, S.M.; Whiteman, A. Socio-Economic Development Drives Solid Waste Management Performance in Cities: A Global Analysis Using Machine Learning. Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=4254784 (accessed on 15 February 2023). [CrossRef]

- Kirsten, J.; Fourie, H. Municipalities Can Play Key Role in South Africa’s Economy Development: Here’s How. News 24. 2021. Available online: https://www.news24.com/news24/opinions/fridaybriefing/johann-kirsten-helanya-fourie-municipalities-can-play-key-role-in-sas-econ-development-heres-how-20211021 (accessed on 20 February 2023).

- Muheirwe, F.; Kombe, W.J.; Kihila, J.M. Solid Waste Collection in the Informal Settlements of African Cities: A Regulatory Dilemma for Actor’s Participation and Collaboration in Kampala. Urban Forum 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Average | Mean | Standard Deviation |

|---|---|---|

| 436.59 | 420.00 | 173.99 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Schenck, C.J.; Chitaka, T.Y.; Tyrrell, H.; Couvert, A. Disposable Diaper Usage and Disposal Practices in Samora Machel Township, South Africa. Sustainability 2023, 15, 9478. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15129478

Schenck CJ, Chitaka TY, Tyrrell H, Couvert A. Disposable Diaper Usage and Disposal Practices in Samora Machel Township, South Africa. Sustainability. 2023; 15(12):9478. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15129478

Chicago/Turabian StyleSchenck, Catherina J., Takunda Y. Chitaka, Hugh Tyrrell, and Andrea Couvert. 2023. "Disposable Diaper Usage and Disposal Practices in Samora Machel Township, South Africa" Sustainability 15, no. 12: 9478. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15129478

APA StyleSchenck, C. J., Chitaka, T. Y., Tyrrell, H., & Couvert, A. (2023). Disposable Diaper Usage and Disposal Practices in Samora Machel Township, South Africa. Sustainability, 15(12), 9478. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15129478