Abstract

This study seeks to explore how owner–managers of small and medium-sized enterprises navigate a constantly changing and turbulent environment following a traumatic experience and how they build resilience in their organizations by drawing upon memories through a complex adaptive system lens. Specifically, this study investigates the major factors shaping the management strategies of SMEs operating in the infrastructure construction sector in North Cyprus, where foreign aid/the patron country is the primary source of financing and therefore the major driver of strategies. To gather primary data, semistructured interviews were conducted with owner–managers of grade 1 construction SMEs, who can participate in internationally financed public projects. A qualitative approach using thematic analysis was adopted, and findings indicate that the most influential factor shaping the management strategies of SMEs in North Cyprus is the macro characteristics of the sociopolitical environment. These characteristics evoke memories for owner–managers and lead to a dissipative approach towards managing their SMEs, creating resilience in the face of North Cyprus’ ever-changing political environment.

1. Introduction

The conventional notion of the “great machine” has been replaced by the concept of a complex adaptive system (CA-S), where the fundamental principle is constant change, shaping our interpretation of the events around us. This perspective is rooted in the belief that the world, including the organizational landscape, will undergo continuous and unpredictable transformations. Consequently, organizations now face a new imperative: to cultivate their resilience and capacity to embrace change with minimal disruption [1,2]. Such changes may lead to innovation but can also be perceived as a disturbance (or a threat), depending on how often and severe they are. These disturbances may originate either internally or externally and can have different effects at different levels. To assess a system’s resilience in the context of disturbances, it is essential to specify the system configuration and disturbances of interest [3]. In this study, the focus is on the environment in which small and medium-sized infrastructure construction enterprises (hereafter referred to as sector SMEs) operate as a CA-S near the edge of chaos or, in the words of Ilya Prigogine [4], as dissipative. This perspective acknowledges that disturbances are inevitable and that the system’s resilience is dependent on its ability to adapt and transform in response to them. In unstable and complex environments, where changes are frequent and sudden, several factors influence a system’s ability to manage and survive change. Understanding how a system adapts to changing circumstances and identifying the factors that influence this adaptability is as complex as the environment itself.

Research into the context and management of SMEs, as Herbane [5] observed, is a mature area of study with multiple subgenres of focus. However, to date, there has been limited research conducted on resilient management strategies of SMEs and how these strategies respond to disturbances [5,6,7,8]. Although previous studies have highlighted the role of culture, individual traits, and increasing social complexities in shaping management strategies [9,10,11], research on proactive management strategies that can enhance resilience in SMEs operating in conflict zones in developing countries (DCs) is still lacking. In a recent study [12], it was noted that only a small amount of research has focused on practical measures to improve the resilience of SMEs in DCs, despite the fact that “enhancing the resilience of construction organizations will lead to a more resilient industry which will be able to respond and recover faster from disasters and therefore continue to contribute their services to communities in the face of major disruption” [13].

Furthermore, Linnenluecke [14] showed that research on resilience is fragmented across several research streams, possibly as a result of context-related circumstances, which motivates research on resilience. However, the lack of frameworks specifically designed to evaluate organizational resilience is another existing challenge, and it is recommended to assess the resilience of an organization after it faces a disturbance [15]. This research is similar in the sense that it is motivated by the ever-changing sociopolitical environment (S-PE) of Cyprus and the events following the warfare in 1974 in Cyprus. The aim of this research is to investigate how sector SMEs navigate disturbances within traumatic societies or environments (such as de facto states) and explore how these sector SMEs endeavour to cultivate resilience in their organizations within this specific context, drawing upon their historical experiences (violent past). Moreover, this research seeks to understand how these organizations adapt and achieve resilience in the aftermath of disturbances, employing the CA-S as a conceptual framework to analyse and interpret their responses. Therefore, the following questions are addressed:

- How do owners/managers of SMEs in a small “developing de facto” country manage ever-changing S-PE and uncertainties?

- How do owners/managers foster resilience within their organizations in such conditions?

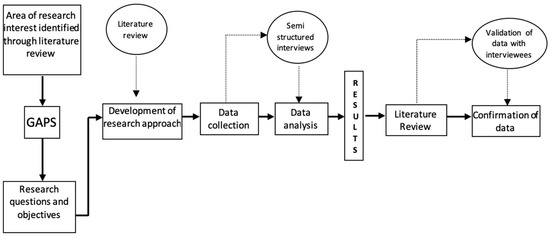

In this paper, we test our postulated hypothesis that a resilient management strategy under stress in traumatic societies is dissipative and nuanced by the owner–managers’ past memories, considering the aforementioned concerns and the existing research gaps with respect to resilience in construction SMEs in turbulent environments. Initially, this is examined through qualitative research via semistructured interviews of 9 of the 12 SMEs (representing 75% of the total population) operating in the infrastructure construction sector in North Cyprus (TRNC), which comprise the exclusive list of companies qualified and authorized to participate in public infrastructure construction projects (financed merely by public funds) as provided by the construction commission office. The research process is depicted in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Research process.

This paper is organized in four sections. In the introductory section, we clarifies the concepts of resilience within the scope of this research (of what), then identify the vulnerabilities of the sector SMEs (to what) and the context of the environment in which the sector SMEs operate (under what circumstances). The conceptual framework of the research is then exposed, and the research hypothesis is developed. Third, we delineate our methodology, including our data, coding, and analysis. Fourth, we present our results and summarize the key findings of the study. Finally, before concluding the implications for researchers, we discuss the limitations of the study and suggest avenues for future research.

2. Literature Review

2.1. De Facto State

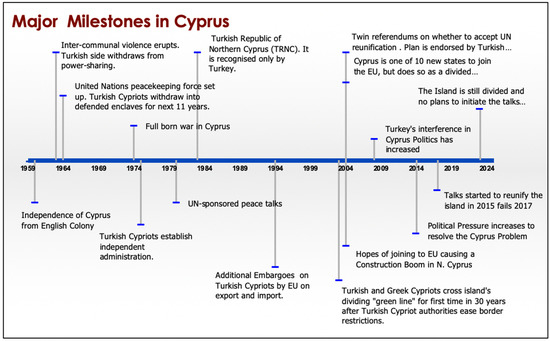

Since the war in 1974, Cyprus has been divided into two separate parts, with a Green Zone controlled by UN forces (Figure 2). As depicted in the Figure 3, the frequency of political unrest on the island since the beginning of the 20th century persists as a problem in the country as a whole. Turkish Cypriots now live on the north part of the island commonly called North Cyprus or the Turkish Republic of North Cyprus (TRNC). However, TRNC is not internationally recognized as a legal state, except by Turkey, therefore functioning as a de facto state. TRNC also faces diplomatic isolation from the rest of the international community, including the United Nations (UN) and the European Union (EU), which hinders its access to non-Turkish external development assistance [16,17,18,19,20]. Turkey’s exclusive recognition of the self-proclaimed TRNC has a profound impact on the local population, both politically and economically. While TRNC meets the classical criteria of statehood in terms of population, territory, and public authority, its independence is far from a reality due to the substantial financial support it receives annually. This creates a patron–state relationship whereby Turkey, an internationally recognized entity, offers political, economic, and military assistance to TRNC [21]. The lack of recognition has a significant impact on the TRNC’s economy and business environment, and the culture of business in TRNC has adapted the characteristics of a de facto state [21,22,23], which can be characterized as distorted and deficient, ultimately serving the people who hold the power and the associated elites rather than the broader population [23,24]. Additionally, de facto states provide an environment that fosters a close-knit relationship between business, social elites, and the government, where all resources and power can be utilized without regulation by an external body, such as the EU [22,23]. The plans to reunite the island (the UN comprehensive settlement plan to reunite the divided island. The Annan Plan) also failed after a referendum in 2004 [25].

Figure 3.

Major milestones (by author). Source: Author (2023).

Figure 2.

Divided Cyprus after 1974 [26]. Reprinted/adapted with permission from Ref. [26]. 2023, Geopolitical Intelligence Services AG.

2.2. Sector SMEs in DCs and in TRNC

Overall, the economic and business environment in TRNC is closely intertwined with the island’s political situation and the lack of international recognition it faces. Despite being open to building relationships with other states in both political and economic realms, their priority often lies in maintaining political separation over economic integration [20,21]. Political considerations in TRNC have historically taken precedence over economic challenges, and the leadership in de facto states closely ties their political and economic goals. Moreover, as a de facto state, TRNC faces the challenge of limited accessibility, as there are no direct flights to the region except from Turkey. Additionally, TRNC businesses are unable to directly export their products outside of the country, rendering it financially unfeasible for them to engage in international markets. Furthermore, the geographical location of TRNC on a small island exacerbates the issue, leading to resource constraints and a heavy reliance on imports from foreign sources. Consequently, businesses in TRNC have to contend with increased transportation costs and additional customs duties as a result of this dependence [21,27,28,29]. The construction industry in TRNC is relatively underdeveloped, considering that its expansion was initiated by hopes for a political solution on the island [30] in 2004 and the fact that it is facing problems typical of the construction industry in other DCs, often at a disadvantage when competing with international firms due to their lack of funds, expertise, and technical and managerial capacity [31,32]. The challenges faced by the sector in DCs are intertwined with the broader economic and social context of these countries. As stated in the literature [33], culture should be applied fully in design and project management in the context of social structures and governance systems and should be viewed within its economic, social, political, and administrative context. According to previous research [34] and as highlighted by the TRNC Competitiveness Report [35], TRNC does not have any significant presence of large-sized or international construction firms, leaving the sector bound to operate exclusively within the confines of the local market [36].

2.3. Infrastructure and Foreign Aid

There is a significant dearth of research addressing the challenges faced by the construction sector in TRNC, with limited recent contributions on this topic. Only a small number of authors have delved into this sector [31,34,36,37,38,39,40,41]. Their findings predominantly reflect general observations pertaining to the building construction industry, as most contractors in TRNC primarily focus on residential projects [34]. According to the latest country statistics, housing construction accounts for 80.90% of the total construction activities in TRNC [42]. Nevertheless, there is a notable absence of research specifically focused on the infrastructure construction industry and how contractors in this sector manage their strategies for resilience, especially considering that a significant portion of the finances in this industry is directed towards larger companies from Turkey. The urgent demand to rehabilitate and improve the country’s infrastructure, combined with a housing construction boom driven by hopes of island unification, has sparked numerous infrastructure projects in North Cyprus (TRNC) specifically targeting transportation and water infrastructure. Additionally, since 2007, increased funding from international sources such as Turkey, the EU, and the UNDP has been dedicated to tackling these challenges [43,44]. Therefore, sector SMEs have potential to undertake larger and more complex projects, in which effective management strategies play a crucial role in achieving success. However, the availability of qualified contractors capable of participating in these ventures is limited. As a consequence, there exists a risk that these opportunities may be appropriated by international firms, marginalizing local contractors—a prospect that has not been well-received within local industry [45,46,47,48,49]. As argued by Farah et al. [50], foreign aid does more harm than good to DCs. The contention is that foreign aid is not an effective tool for growth and development. Furthermore, it is argued that foreign aid creates dependency, sustains authoritarian governments, and fosters corruption.

The objections raised by the Building Contractors Association (TRNC-CA) regarding the tender conditions of construction projects funded and tendered by the EU and Turkey serve as evidence of this concern [50]. According to member contractors, the tender conditions placed local contractors at a disadvantage, as no contractors in TRNC could fulfil the criteria for these tenders. They further cautioned the government against allowing public tenders to be accessible to large foreign or international companies [45,46,47,48,49]. Similarly, protests were witnessed in other infrastructure projects primarily financed and tendered by Turkey (as these projects were tendered in Turkey), thereby preventing Turkish Cypriot contractors from participating. However, these protests and objections were unsuccessful, and the tenders were awarded to large construction companies from Turkey. In September 2012, a Turkish company was granted a significant public infrastructure construction project to upgrade the country’s sole airport [47]. However, despite the considerable duration that has elapsed, the airport remains non-operational as of early 2023. Another noteworthy project involved the construction of an 80 km pipeline financed by Turkey with a budget of EUR 300 million to facilitate the transmission of freshwater to the island through the Mediterranean. This project, which was also tendered in Turkey and awarded to a Turkish company, was successfully completed in 2015. Furthermore, in 2020, Turkey initiated a tender for the repair of the aforementioned pipeline, known as the “TRNC Sea Crossing Transmission Line Repair” [51]. The tender was awarded to a Turkish company. In 2021, another significant contract was awarded to a company in Turkey for the rehabilitation of 110.7 km of a village road, a project that was completed in January 2023. Additionally, two major highway projects were awarded to companies from Turkey without going through a tender process in TRNC [48,49]. Although it has been suggested that international companies can foster innovation in local construction industries in DCs [52], this does not seem to be the case in TRNC. Interestingly, local contractors in TRNC have not embraced international competition, and they feel marginalized by the tender procedures [45,46,47,48,49].

3. Methods

In the preceding sections, a synthesis of existing research and theories was presented, with a specific focus on examination of the influence of sociopolitical conflicts and disturbances on the management strategies employed by owners/managers in the sector. This analysis specifically utilized infrastructure construction SMEs in TRNC as a case study. The literature review has highlighted a research gap concerning the impact of the S-PE on management within the sector of vulnerable DCs such as TRNC. This gap necessitates further investigation as suggested in the literature [12,52]. The aim of the current study is to address this research gap by specifically focusing on soliciting perspectives and insights from sector SME owners/managers who regularly confront challenges and disturbances arising from the unstable external environment prevalent in TRNC. The aim is to understand how these individuals foster resilience under such circumstances. To achieve this, it is crucial to explore their personal and professional experiences within the sector and the broader environment in order to identify unique themes that can contribute to the existing literature and suggest potential areas for future research and development. To investigate this topic, a qualitative methodology was adapted, employing semistructured interviews with open-ended questions as the primary approach for data collection. The key informants selected for this study were the owners/managers within the TRNC sector.

Qualitative research, as Yin states [53], is valuable because it allows us to study real-world situations and understand how people navigate their lives in those contexts. It captures the rich details of everyday experiences. By focusing on specific groups of people, we can gain insights into their perspectives. Rather than having a single definition, qualitative research is characterized by five important features. It seeks to understand the meaning of people’s lives in real-world conditions, represent the views of participants, consider the context in which people live, contribute to our understanding of human social behaviour, and use multiple sources of evidence. The motivation for utilizing qualitative research in this study aligns closely with Yin’s perspective [53], emphasizing the importance of prioritizing the viewpoints of research participants and gaining insight into their subjective interpretations, actions, and contextual influences. In this case, the focus is on understanding the perspectives of owners/managers of sector SMEs in TRNC.

Qualitative research can also be divided into two main categories. The first category consists of analytical approaches that are associated with a particular theoretical framework, such as grounded theory, discourse analysis, and narrative analysis. In contrast, the second category is not bound by any specific theoretical framework and adopts a more independent and experiential approach to analysis. Thematic analysis (TA) falls into this second category, making it a versatile and adaptable research method compared to other qualitative techniques. TA allows for the creation of a comprehensive and detailed understanding of the dataset, enabling researchers to explore the data in depth [54,55,56,57,58]. Therefore, TA was used to analyse the data (see Section 3.2 for detailed explanation), to explore owners/managers’ personal and professional experiences in this sector and broader environment, to identify unique themes and contribute to the literature, and to suggest areas for further research and development.

3.1. Study Participants

Prior to developing the research methodology, TRNCTRNC-CA, the only association monitoring the qualifications of contractors in TRNC, was contacted to acquire necessary information about contractors who are qualified to participate in publicly tendered infrastructure projects by the government. The TRNC-CA provided a list of contractors along with their classifications, which enabled the researcher to identify contractors eligible for participation in publicly tendered infrastructure projects. TRNC-CA guidelines authorize only grade 1 sector SMEs to undertake major public infrastructure projects, particularly those that are funded by foreign aid and require more technical knowledge and stringent project specifications. After the evaluation of the list provided by TRNC-CA, only 12 grade 1 sector SMEs were identified that met the required criteria set by TRNC-CA.

To identify suitable interview subjects for the study, the researcher established inclusion and exclusion criteria, as shown in Table 1. As Table 2 shows, all the participants are owners/managers and Cypriots (born in Cyprus), and their companies are all small with very few full-time employees. The participating sector SMEs, encompassing 75% of all grade 1 sector SMEs in TRNC as reported by TRNC-CA, demonstrate variation in terms of employee count and annual turnover. It is important to highlight that the author maintained a neutral stance and did not have any direct involvement with the companies under study. Furthermore, the author adhered to the principles of reflexivity to prevent biased interpretation of the results.

Table 1.

Participant selection criteria.

Table 2.

Baseline characteristics of the study participants (n = 9).

3.2. TA and Validation of the Data

Before conducting the interviews, a semistructured, open-ended questionnaire was developed (see Appendix A). The questionnaire was designed to gather information on various topics, including the role of the owner/manager, management structure, available expertise, decision-making processes, stakeholder management, and future investments. Additionally, the questions aimed to uncover how the history and S-PE of TRNC impacted the sector SMEs. The questionnaire was refined through multiple iterations to enhance the validity of the research. Prior to conducting the interviews, all participants were given a comprehensive explanation of the consent form and provided with detailed information through a participant information sheet. The purpose of this was to ensure that the participants had a clear understanding of the research being conducted and the rationale behind their selection. The interviews, lasting 90 min to 2 h each, were conducted in private locations chosen by the participants and led by the researcher. To maintain confidentiality, the nine participants were assigned labels such as Owner A, Owner B, and Owner C, while their companies were labelled accordingly, i.e., as Company A, Company B, etc.

TA, as outlined by Kieger [54] and Clark et al. [55], is a qualitative data analysis technique that entails systematic exploration of a dataset to identify, analyse, and document patterns that repeat. It serves as a descriptive method of data analysis while incorporating interpretation through the selection of codes and construction of themes. The primary objective of TA is to identify and describe implicit and explicit ideas within the text, known as themes [55,56], which capture significant aspects of the data in relation to the research question. TA is widely regarded as the most suitable approach for qualitative studies aiming to uncover insights through interpretation. It is important to note that TA does not involve simply tallying the frequency of recurring words or phrases; rather, it entails a systematic process of encoding qualitative information [54,55,56,57,58]. As Clark et al. state [55]:

“TA is unusual in the canon of qualitative analytic approaches, because it offers a method—a tool or technique, unbounded by theoretical commitments—rather than a methodology (a theoretically informed, and confined, framework for research). This does not mean that TA is a theoretical, or, as is often assumed, realist, or essentialist. Rather, TA can be applied across a range of theoretical frameworks and indeed research paradigms”.(297)

After translating and transcribing the data, they were imported into NVivo qualitative data analysis software for coding purposes. This software proved to be a highly efficient means of managing and organizing the data, thereby reducing the time and effort required for manual analysis. By linking text to codes, grouping codes, and modifying them as necessary, the software enabled the researcher to refine the analysis, resulting in a more accurate and comprehensive construction of meaning while minimizing errors. For the coding process, the author adhered to multiple stages recommended in the literature [56]. In the initial phase, the researcher conducted an assessment of the coded text to ascertain its consistency and detect any potential overlaps with other codes. Then, the researcher proceeded with the identification of fundamental underlying ideas, assumptions, and conceptualizations central to TA. This step involved extracting text that formed the basis of repeated patterns (themes) across the dataset. Subsequently, pertinent extracts of coded data were gathered and organized under the identified themes, while emergent codes were scrutinized in relation to the research questions. The themes were subsequently refined and fine-tuned, leading to identification of subthemes. Finally, the themes and subthemes were finalized, and the data were analysed within them. In early 2023, the study results were presented to all the participants, who agreed with the main observed patterns.

3.3. Limitations of the Study

This study focused solely on infrastructure construction companies in TRNC, and the initial data were collected by the author before the COVID-19 pandemic [59]. After the COVID-19 pandemic, the author, realizing similar occurrences in the infrastructure construction sector (see Section 2.3), decided to check the initial findings of the research and test the results with the same group in early 2023 without additional in-depth interviews. This might be a weakness of the research; however, all participants agreed with the results and confirmed that not much had changed from the time of the initial interviews. Furthermore, it is important to acknowledge that while the findings of this study are specific to the infrastructure construction industry, they may not be generalizable to other construction sectors or SMEs in different fields. Another limitation of this study is the inclusion of only 9 out of the 12 identified infrastructure construction companies, resulting in a small sample size. Although interviews were conducted with owners/managers from 11 companies (with consent obtained from each company), two participants declined to have their interview transcripts included for analysis. As a result, only nine interviews were analysed. However, it should be noted that there were only 12 qualified infrastructure companies available for study, and the companies included in the research represent 75% of the total qualified grade 1 infrastructure companies in TRNC. The aim of this research was to gather rich and in-depth data from approximately five or six companies, but thematic saturation was achieved with the sample size of nine. According to Yin [60], multiple case studies can provide strong support for initial propositions with six to ten cases, and sample size should be determined by the point of saturation.

Additionally, as in previous studies in the sector [30,31,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41], the author faced a limitation in the form of a lack of reliable data and statistics regarding the construction sector in North Cyprus (TRNC). The scarcity of dependable statistics, as noted in the literature [61], continues to present a significant challenge for research in this field. Therefore, the author heavily relied on personal observations and direct industry-specific data collected for this study. Despite this obstacle, the research provided valuable insights into the management strategies of SMEs and shed light on the impact of social and political factors on management practices in the infrastructure construction industry in TRNC. It is important to acknowledge this limitation and interpret the findings with caution, considering the available data in this particular context.

4. Findings

The aim of the current study is to explore how the owners/managers of SMEs in a vulnerable DC manage turbulence and uncertainties (disturbances)—both political and social—in order to achieve resilience within their organizations. This is achieved by investigating and understanding the factors shaping the owners/managers’ management strategies within of their own context. As mentioned by Saad et al. [12], it is important that we conduct resilience research focused on the context of SMEs. Furthermore, having insight in how SMEs act to deal with challenges in different business environments is pertinent to enrich the applicability of the concept in the real world [57,62]. Consequently, this section analyses the data gathered for the research using extracted references from the coded text. The findings reveal distinct levels of themes, including overarching main themes and corresponding subthemes nested within them. A ‘theme’ is characterized as encapsulating “something significant about the data in relation to the research question and signifies a degree of patterned response or meaning within the dataset. Subthemes, on the other hand, are regarded as themes-within-a-theme, providing further granularity and depth to the analysis and structuring main themes” [54,55,56].

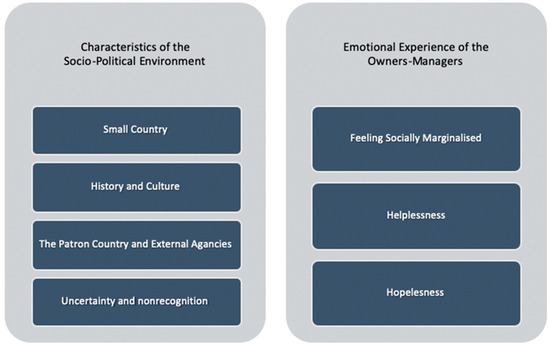

In the concluding stage of data analysis, numerous primary themes and subordinate subthemes were detected. Nonetheless, for the explicit purpose of addressing the central research inquiries, solely two primary themes and their corresponding subthemes are presented herein (refer to Appendix B for the coding framework). A thematic map was created to visually illustrate the two main themes identified in the study. Figure 4 presents these themes, along with their respective subthemes. Table A3 and Table A4 in Appendix C present illustrative examples of coded text segments corresponding to each subtheme.

Figure 4.

Emergent themes and subthemes.

The first theme, ‘Characteristics of the Socio political Environment’, was found to be the most influential in shaping the perceptions of external environments of owners/managers connected to their business context. This theme was further broken down into four subthemes (two social and two political). The social subthemes are: ‘Small Country’ and ‘History and Culture’. The political subthemes are: ‘The Patron Country and External Agencies’ and ‘Uncertainty and Non-recognition’. The first theme captures the external factors that shape the environment surrounding the sector SMEs. It encompasses aspects such as the historical background, cultural influences, political dynamics, and demographic characteristics of the country. The second theme, titled ‘Emotional Experience of the Owners/Managers’, comprises three subthemes: ‘Feeling Socially Marginalized’, ‘Helplessness’, and ‘Hopelessness’. These subthemes shed light on the underlying defensive responses exhibited by owners/managers. This second theme delves into the perceptions of owners/managers in the sector, exploring the challenges they face due to ongoing changes and their efforts to adapt to these transformations.

4.1. Theme 1: Characteristics of the S-PE

Like organizations in all cultures and sectors, the sector in TRNC is subject to external forces that constantly impact organizational management. This study highlights the significant influence of the S-PE in TRNC, which specifically affects the management of the sector SMEs. The environment is marked by high levels of uncertainty, making it challenging for sector SME owners/managers to predict or cope with its effects.

The supporting interview extracts relevant to the subthemes are listed in Appendix C, Table A3, and a summary of the surfaced subthemes is listed in Table 3.

Table 3.

Summary of the subthemes from the extracts, Theme 1.

4.2. Theme 2: Feelings of the Owners/Managers

SMEs’ management strategies are influenced by both external environmental forces and internal elements related to the owners/managers themselves. The literature [63] and research data show that SME owners/managers’ personalities are crucial to how they run their businesses, as personal values and goals cannot be separated from business goals. In TRNC, the sector SMEs’ management strategies are reactive due to the conflict and challenges in the society. The literature [64] and research findings confirm that SMEs’ management activities depend on the owners/managers’ characteristics and context, with strategy making being informal and intuitive, shaped by the owners/managers’ mentalities. The supporting interview extracts relevant to the subthemes are listed in Appendix C, Table A4, and a summary of the surfaced subthemes is listed in Table 4.

Table 4.

Summary of the subthemes from the extracts, Theme 2.

4.3. Discussion of the Results

4.3.1. Characteristics of the S-PE

The S-PE of TRNC is marked by significant uncertainty and instability, posing considerable challenges for SME owners/managers in the construction sector when it comes to long-term planning. Throughout the research, these owners/managers consistently expressed concerns about making additional investments in their companies due to the prevailing uncertainties. Their decision-making processes were often shaped by past experiences, including perceptions of unjust treatment. As one owner stated, “Turkish Cypriots are deceived and there is an unfair treatment” (Owner F). The literature suggests that fear of experiencing victimization again, coupled with vivid personal memories of past events, serves as a significant reference point for decision making within organizations [65,66]. Consequently, the sector SME owners/managers, including those examined in this study, adopt “rent-seeking” behaviour [67], whereby they seek to gain advantages from the decisions made by policymakers or attempt to influence these decisions themselves. Given the absence of a reliable “rule of law” in de facto states, personal connections prove to be a much more effective means of securing rights, privileges, and benefits compared to official channels [68]. The findings of the present research align with this observation, indicating that such behaviour is fostered by the uncertain environment and past experiences, leading to disregard for effective management practices. One participant expressed this sentiment, stating, “I don’t want to be mean but we feel that the construction companies who are close to the government always get the projects. We believe that.” (Owner G). As a result, many owners/managers demonstrated a lack of motivation or interest in initiating change within this unpredictable context. For instance, one owner stated, “I am not planning to make any changes... there is no future.” (Owner A). The study participants frequently expressed that their personal and professional values and beliefs were incongruent with those of the patron country (pC), leading them to adopt a protective stance towards their own identity. In countries such as TRNC, which have a cultural emphasis on collectivism, owners/managers rely on their ingroups (family, organization, etc.) for support and, in return, demonstrate firm loyalty to these entities [13,69]. This study highlighted the significant influence of the pC and its excessive control over the politics of TRNC, as emphasized by the owners/managers. They perceived a lack of control over the country’s future, both socially and politically, and viewed S-PE changes as threats to their social norms. One respondent’s comment resonated with the sentiments of many, stating: “The Turkish Cypriot community will disappear slowly... they don’t want us to gain economic power... so the Turkish Cypriot population will be alienated... the Turkish Cypriot community will be differentiated... I have lost my hope about the agreement [end of conflict on the island]... I don’t have any expectations at all.” (Owner C).

It appears that, while the involvement of the pC was more readily accepted in the past, the increased level of control exerted by the pC is now perceived as threat. Consequently, this cultural dimension has intensified, leading to a distorted perception of the adversary and hindering the willingness of owners/managers to take responsibility for the construction sector, as they perceive their efforts to be largely futile. Therefore, it can be argued that excessive external political control over a society can be regarded as a threat (disturbance) that contributes to the absence of effective management strategies, as exemplified by the sector SMEs in this research.

The management strategies of the sector SMEs in TRNC are influenced by various factors, including historical and cultural influences, the smallness of the state, lack of international recognition, political uncertainty, and the pC’s influence. Operating within a small state with limited resources amidst an ongoing conflict on the island where the local community feels neglected by the international community has potentially provided an opportunity for the pC to exert control over the country’s politics. Consequently, this hinders owners/managers in developing long-term planning strategies for their SMEs. Despite their efforts, the collective belief among owners/managers is that they lack control or influence over the sector and the politics of their country. This suggests that these external factors significantly impact the management strategies of the sector SMEs in TRNC.

4.3.2. Emotional Experiences of the Owners/Managers

Memories and recollections of past events have a profound influence on the behaviour and beliefs of the sector owners/managers. Despite the absence of current violence on the island, the dynamic S-PE and the uncertain future of the sector in relation to the long-standing Cyprus Problem contribute to a unique form of trauma among owners/managers, shaped by their shared memories. The literature supports this notion, highlighting that the owners/managers of SMEs not only endure the economic consequences of historical disturbances but also continue to be impacted by them, influencing their activities and decision making [70]. It is not the direct experience itself but rather the recollection of it that produces a lasting traumatic effect [71]. Consequently, the sector owners/managers’ remembrance of these disturbances and the ever-changing S-PE within the sector shape their behaviour and serve as a justification for their practices. This finding emphasizes the significant role of memories in guiding the strategic management approach of the sector SME owners/managers. The future for these owners/managers is unclear: “if this situation goes on, then only one or two companies would remain in infrastructure in North Cyprus within several years… I mean that’s what I predict. If someone wants to buy my asphalt plant, I would sell.” (Owner D). It is widely acknowledged that de facto states and businesses rely heavily on external support for their survival. However, the sector SMEs participating in this study expressed a strong collective opinion that such support undermines their independence and long-term viability, clouding their prospects. Regardless of the source of the international financial aid, local sector SMEs in TRNC often find it challenging to meet requirements set by the external agencies due to limited capacity and resources. Based on the gathered data, it is evident that these agencies attempt to induce changes among the sector SMEs by imposing demanding specifications in tenders and projects. In the research, these demands were widely viewed as unrealistic, and the required changes to meet them were seen as a threat to the organization’s identity. It should be noted that the identity of SMEs is closely linked to the identity of the families and the local communities they represent [72]. This sentiment aligns with Ulas’ discovery [73] that a cultural genocide is occurring against the Turkish Cypriot population in TRNC. The participant sector SMEs strongly emphasized the need to protect the local identity of their organizations, as any change would involve moving away from that identity. This sentiment was reinforced throughout the interviews, where it became evident that there is a sense of antagonism towards external agencies among the owners/managers of the sector SMEs. They expressed frustration regarding the exclusion of local companies from projects, which could have facilitated knowledge transfer and accelerated progress and growth within the local infrastructure construction industry. One of the respondents remarked, “the companies are facing some problems but they are very flexible; they can grow or they can become smaller.” (Owner G). This observation aligns with the existing literature on SMEs, which highlights the correlation between SME growth and their capacity to absorb learning and accumulate the necessary knowledge for future growth phases [74].

4.4. Research Questions and Findings

Research question 1 (RQ1) focused on investigating the key factors that influence the management strategies of the sector SMEs in TRNC. Through a comprehensive TA, two prominent themes emerged, representing the discussed factors. TRNC, as a small nation, primarily consists of owner-managed SMEs. Similar to previous studies conducted in DCs [52,75], globalization significantly influences the growth of the sector SMEs in TRNC. Additionally, the influx of foreign assistance, including financial aid from external governments or entities such as the EU aimed at improving the country’s infrastructure, has led to an increase in the presence of foreign contractors conducting operations in TRNC. This, in turn, poses significant challenges for the sector SMEs.

While SMEs in small and DCs generally encounter challenges associated with their intrinsic characteristics, SMEs in TRNC face an additional layer of complexity resulting from a distinct amalgamation of factors. The region, characterized by limits of its land area and division due to political conflict and recent warfare, adds to the uncertainty and unpredictability of the S-PE. Furthermore, as a de facto state lacking international recognition, daily business activities are further complicated. The management strategies of the sector SMEs in TRNC are highly affected by the political environment rather than the economic environment. This is evident in the daily negotiations and lifestyle surrounding the Cyprus Problem, wherein companies and society alike cannot predict the future, and management is aligned with the changing politics of the country. Consequently, future planning loses its significance, and the management of the sector SMEs primarily revolves around the political landscape. The impact of the S-PE is on the sector SMEs is profound. The S-PE has evolved into another realm due to the constant upheaval and a history of traumatic conflicts that still haunt the memories of the sector SME owners/managers. The perpetual external pressure, fuelled by the pC, only adds to the trauma and conflict already present in the S-PE. Such circumstances serve as a stark reminder of the past when the sector’s growth was impeded and often halted by uncontrollable external factors beyond the control of the local industry.

The second research question (RQ2) seeks to explore how the sector SMEs in TRNC foster organizational resilience. The findings presented earlier imply that the sector SMEs in TRNC operate within a complex system. By comprehending the interplay between the system variables, one can better understand how the sector SMEs implement their management approaches and respond to changes in the S-PE. Furthermore, this understanding helps to address the disturbances/threats that arise as a result of these changes. As indicated in the existing literature [76,77], “the resilience of a system depends on its adaptive capacity (AC), which comprises a set of variables and their interactions that allow the system to respond to disturbances”.

Disturbances to a system can arise from either internal factors, such as the values held by SME owners/managers, or external factors, such as the S-PE in TRNC. The definition of system boundaries and the time scale of analysis are also pivotal elements in assessing the resilience of a system, as underscored by previous research [3,78,79]. In this research, the boundaries of the system are defined as ‘the infrastructure SMEs in TRNC’, ‘the SME owners/managers’, and ‘the S-PE in TRNC’. The time scale is identified from the analysis of the results and is divided into three different phases, each with distinct approaches to management observed in the interview results. The initial phase encompasses the years 1974–1994, during which SMEs embarked on the process of adjusting to the changed circumstances following the island’s separation. The subsequent phase spans from 1994 to 2004, characterized by growth within SMEs and the anticipation of a political resolution on the island. Lastly, the period after 2004 signifies the emergence of the infrastructure construction sector as subservient to political factors, primarily due to the rejection of the Annan Peace Plan and depletion of hopes for an immediate political solution on the island.

4.4.1. First Phase: Adaptation and Transformation

The period immediately after the 1974 war in TRNC was characterized by changes and uncertainties in the sociopolitical environment, particularly in the construction sector. According to Ingirige et al., “small enterprises have fewer resources to plan, respond and recover” and are “least prepared of all organizations when faced with disturbances” [80] (p. 598). The external disturbances in this environment affected the management of SMEs in the sector. Some of these disturbances in the S-PE are sudden, and some build gradually until a threshold is reached [76].

Despite their limited resources, the sector SMEs in TRNC were able to respond and adapt to these changes, leading to the formation of the TRNC-CA in 1994. This formalization helped the sector SMEs participate in infrastructure construction projects, leading to a growth phase and highlighting their adaptive capacity and resilience. As Vossen [81] noted, “rapid response to environmental change and turbulence, alongside quick learning, and adaptation of management strategies, are important characteristics of small enterprises”.

The dynamic and uncertain S-PE, marked by frequent fluctuations, was observed to instigate specific alterations in the in the management strategies of the participant sector SMEs. However, these changes, rather than being deliberate, were largely influenced by the demands of the ever-changing external environment. This behaviour can be expected, as SMEs typically possess limited resources [80] and are often ill-equipped compared to larger organizations when confronted with disturbances.

4.4.2. Second Phase: Growth and Persistence

SMEs are characterized by their limited resources, which greatly influence their growth strategies, as well as their ability to operate with greater external uncertainty than larger organizations [82]. In TRNC, this uncertainty is exaggerated by the unstable political environment. TA revealed notable growth in the sector, encompassing both the scale and capabilities of the sector SMEs. However, this growth did not materialize through deliberate long-term strategies but, rather, through rapid expansion driven by optimistic anticipation of a resolution to the Cyprus Problem. Consequently, the sector SMEs became increasingly susceptible to disturbances. Contrary to previous research [83], the growth phase did not precipitate transformations in the structure of the sector SMEs, which persisted as family-based organizations dictating management strategies and serving as a key factor of resilience. Despite the literature suggesting strategic business planning as a means of creating resilience [6], the research respondents did not perceive it as such. This study revealed that, despite vulnerability being acknowledged as a complementary aspect of resilience [84], persistence emerged as a more crucial component amongst participant sector SMEs. The body of research on resilience [85,86] provides diverse perspectives on vulnerability, although there is a consensus that systems or individuals can display vulnerability to disturbances in certain instances while not to others. Additionally, they may be susceptible to specific disturbances but resilient to others. Resilience, as mentioned in the literature, is “a measure of the persistence of systems and of their ability to absorb change and disturbance and still maintain the same relationships between populations or state variables” [87] (p. 14). An increased level of uncertainty in the S-PE, as observed during this period, boosts the flexibility and responsiveness of the sector SMEs. These attributes, which are key components of adaptive capacity, contribute to increased resilience, as suggested in the literature [88]. It is noteworthy that adaptive capacity does not pertain to change but to the system’s capacity to assimilate and withstand disturbances. The resilience of the sector SMEs in TRNC is arguably dependent on the skills and capabilities of their owners/managers. Their ability to ensure the robustness of their SMEs in the face of significant disturbances aligns with the established understanding of resilience [87,88,89].

4.5. Operating Near the Bifurcation Point

According to insights from the CAS domain [76,77,87,90], resilience exhibits inherent boundaries. Once these boundaries are surpassed, the system undergoes a transformation, leading to a reduction in resilience until an unforeseen event triggers a collapse [87,90]. Echoing Hartling’s perspective [89] (p. 53), “resilience is all about relationships”. The interconnectedness among populations or variables within a system serves as the primary wellspring of resilience, fortifying individual attributes associated with resilience in the aftermath of disturbances [87,91,92]. Hence, the intervention of the pC in the S-PE of TRNC and its dominion over infrastructure projects since 2004 have instigated profound changes in the market dynamics of the sector. Furthermore, external agencies have imposed demands that surpass the capabilities of the sector SMEs in TRNC, including demanding project specifications aligned with international requirements, intricate payment procedures, and the inconvenience of distant arbitration locations such as Brussel or New York for most sector SMEs. Moreover, local politicians have relinquished their influence to the pC, stripping the sector SMEs of their capacity to shape the sector’s politics through relationships with these politicians. These collective events can be regarded as disruptive forces that have impacted the system of the sector SMEs in TRNC, resulting in a reconfiguration of the sector SMEs’ relationships with the industry and the S-PE, thereby amplifying their vulnerability.

As evident from the analysis, the interviewed owners/managers expressed a sense of helplessness and vulnerability for their organizations, perceiving limited prospects for future recovery. The multifaceted and contentious changes induced by the aforementioned events have led to sporadic growth of participant sector SMEs in this study. Additionally, this study reveals that the sector SMEs are currently engaged in diversification across other sectors or downsizing, signalling a phase of reorganization aimed at enhancing resilience.

The future trajectory of these SMEs remains uncertain, as their systems’ vulnerability is strongly influenced by external variables. The interconnectedness of all system agents indicates that managing the sector SMEs in TRNC extends beyond the sum of its individual components. Instead, it revolves around the ever-changing relationships among these agents, which are contingent upon disturbances and reminiscent of a dissipative structure [74,93,94]. This finding suggests that SMEs are operating at the “edge of chaos” [95], characterized by high instability and self-organization as a spontaneous and unpredictable strategy. According to existing literature [96], organizations transition from their existing state following a breakdown of internal or external structures. This transformation involves a period of experimentation during which the organization selects a new behavioural pattern aligned with its available resources. By embracing their role as dissipative structures, the sector SMEs maintain their adaptability to disturbances, continuously experimenting and adapting to address the challenges they encounter. As the literature suggests, these systems would ultimately become “self-referencing, drawing upon its own history and accumulated learning to bring forth new structures and processes” [97] (p. 709).

4.6. How Do the Sector SMEs Foster Resilience?

The resilience of the sector SMEs within the context of this research was found to lie in the adaptation of management strategies of the sector SME owners/managers in the presence of disturbances by experimenting and adjusting themselves to the existence of disturbances throughout their history. The development of resilience in the sector SMEs is influenced by various factors, such as the unique characteristics of the sector, the context of the S-PE, and the values held by the owners/managers. In addition, resilience encompasses temporal and spatial dimensions and emerges naturally through the interplay of these factors, as highlighted in the literature [89].

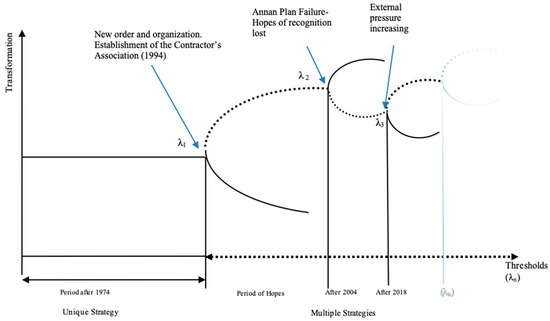

Analysis of the research findings indicated that that the external political environment holds more significance in shaping management strategies compared to the internal characteristics of the sector SMEs. The resilience of the sector SMEs is primarily influenced by the perceptions of owners/managers regarding the S-PE, which are influenced by the historical background of their country. In the literature on resilience, attributes such as motivation, perseverance, flexibility, and optimism are emphasized as crucial qualities of resilient individuals [98,99]. These same factors are believed to enhance resilience in the sector SMEs. Despite exhibiting low levels of motivation and optimism, the participant owners/managers examined in this study displayed characteristics of flexibility and perseverance. These characteristics were further enhanced by their cultural traits, specifically their collective mindset, which inspires their motivation for survival. The sector SMEs do not engage in proactive planning; instead, they respond to the opportunities and disturbances arising within the S-PE, shaping their strategies in a spontaneous manner. Their resilience is not about adaptation to change but about being robust to protect themselves from disturbances by creating new solutions for their survival. As Folke [94] stated, resilience is “not only about being persistent or robust to disturbance. It is also about the opportunities that disturbance opens up in terms of recombination of evolved structures and processes, renewal of the system and emergence of new trajectories”. The sector SMEs are operating in a potentially chaotic state, near the bifurcation point, as modelled in Figure 5. The resilience of the sector SMEs is evident in their adaptive responses to disturbances, exhibiting flexibility and perseverance while strategically selecting the most advantageous course of action. The dissipative structures reveal that changes occurring at the bifurcation point are irreversible. With each crossing of this point, the sector SMEs develop new strategies to remain competitive, leaving uncertainty regarding the path the sector SMEs will choose when faced with their next disturbance.

Figure 5.

Dissipative behaviour of the sector SMEs in TRNC.

4.7. Summary of the Findings

Section 4.4 focused on addressing RQ1, which aimed to identify the factors that influence the management strategies of the sector SMEs in TRNC. The discussion also delved into the owners/managers’ perceptions of these factors within the unstable and unpredictable S-PE of TRNC, which introduces considerable uncertainties. Several factors, including reliance on support from the pC and the preservation of culture and history, have impacted the values and beliefs of owners/managers, thereby altering their perspectives on their businesses and hindering their ability to formulate long-term management strategies for growth.

Moving to the second research question (RQ2) the discussion centred around the manner in which management strategies implemented by the sector SMEs have fostered and continue to foster resilience. Emphasis was placed on the intricate interconnections among the different agents within the sector SMEs in TRNC, revealing that management strategies are shaped by a multitude of internal and external factors while operating within an ever-changing S-PE. The current dissipative structure of the system necessitates SMEs to constantly adjust to the shifting environment, making it impossible to predict their future growth, downsizing, or sector change.

While the sector SMEs in TRNC experience vulnerability during certain periods, they also display higher resilience during other periods. Owners/managers of the sector SMEs rely on available resources and select adaptable strategies to foster resilience within the unpredictable and unstable S-PE of TRNC. Resilience emerges and evolves in response to specific circumstances and challenges. The analysis indicated that owners/managers, who are responsible for nurturing the sector SME resilience, exhibit four key behavioural traits: flexibility, perseverance, motivation, and optimism. Although their motivation and optimism may fluctuate, their ability to generated diverse solutions to navigate S-PE disturbances and their determination to safeguard their identity contribute to the resilience of the sector SMEs.

5. Conclusions

This article examines the concept of resilience in the sector SMEs and investigates their ability to adapt to changes and disruptions in their S-PE. Resilience is defined as the capacity of SME owners/managers to experiment with and adjust their management strategies over time. This study identifies several factors that contribute to resilience, including the S-PE context and the emotional experiences of the owners/managers. However, it also recognizes that resilience is influenced by temporal and spatial factors that interact naturally.

The analysis explored the major determinants of management strategies in the sector SMEs by examining their responses to environmental disturbances. This study reveals that the external S-PE has a more significant impact than internal characteristics on shaping management strategies. Moreover, the perceptions of owners/managers, which are influenced by the historical backdrop of their country, play a crucial role in driving the resilience of their sector SMEs. This article emphasizes the importance of motivation, perseverance, flexibility, and optimism as critical attributes of SME owners/managers.

The findings reported herein demonstrate that the sector SMEs in TRNC can experience growth, diversification, or downsizing based on available project opportunities, but organizational changes are not necessarily correlated with growth. Instead, changes in the S-PE and the ability of owners/managers to cope with disturbances exert influence. The ever-changing S-PE compels the sector SMEs to devise novel solutions to manage disturbances, and certain changes can reduce resilience by increasing vulnerability. The owners/managers considered in this study exhibited reactive behaviour, capitalizing on the opportunities presented by the S-PE and formulating strategies in a spontaneous manner

Additionally, this study highlights the significant influence of past traumatic events on present management strategies and the reciprocal impact of current disruptions on past experiences, both of which shape the resilience of the sector SMEs. The S-PE in TRNC profoundly affects the behaviour of owners/managers in the sector SMEs, with positive feedback amplifying the unpredictability of management strategies. Resilient SMEs typically exhibit characteristics reflective of their owners/managers, such as flexibility, perseverance, optimism, and motivation. Although SME owners/managers in traumatized societies may exhibit low levels of optimism, they demonstrate heightened levels of flexibility and perseverance, with their motivation bolstered by their collective orientation.

While research on business and exogenous shocks has predominantly focused on large firms, particularly multinational corporations, it is essential to recognize the distinct characteristics and challenges faced by SMEs. SMEs often exhibit greater vulnerability than large organizations under the influence of different disturbances. Furthermore, the impact and experience of different types of disturbances can vary significantly among SMEs. Therefore, it is crucial to contribute additional findings to the literature on the resilience of SMEs, especially in DCs, deepening our understanding of their adaptive strategies within their specific contexts. This study posits that the resilience of SMEs resides in their ability to adapt their management strategies by experimentation and adjustment in response to disturbances throughout their history. By contributing to the understanding of management strategies in SMEs affected by social trauma, the aim of this study is to inform policymakers in conflict-affected areas. Furthermore, it calls for further research on resilience in construction SMEs in DCs, particularly those facing challenges in their S-PE, to foster more resilient communities. Future research should delve into the unique dynamics of SME resilience in DCs, exploring mechanisms to enhance resilience, identifying best practices, and examining contextual factors and financial aid strategies that influence SME resilience. Such endeavours hold practical implications for policymakers, sector practitioners, and stakeholders invested in the growth and sustainability of SMEs in diverse contexts.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with Research Ethics Committee 5 (Flagged Humanities) of University of Manchester and approved by the Research Ethics Committee (decision number- Project Ref 12144, September 2012).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Appendix A. Questions

Table A1.

Interview Questions.

Table A1.

Interview Questions.

| Questions Asked |

|---|

| Will you talk me through when your company was established and what were the reasons? |

| Explain your role and position in the company? |

| In your view who are the company’s stakeholders? |

| What type of projects your company handle? |

| Please explain to me a memorable project you and your company were involved with. (challenges/opportunities/barriers)? |

| How did you control the project? Did you use any management practices to help you? |

| What challenges do you face when you try to adopt new management practices in the projects? |

| Are you aware of other project control practices used in the industry to manage projects? |

| Over the years, have you noticed any differences in how you managed the projects? |

| Running a business in a de facto state, does it bring a different set of challenges to company? |

| In what way do you manage the client—company relationships? |

| Have you observed any changes in the management style of the clients over the years? If so, can you explain? |

| Where do you see the company in 5–10 years’ time? |

| How will you bring the changes in the company? |

Appendix B. Coding Framework

Table A2.

Coding framework.

Table A2.

Coding framework.

| Exploration | Code | Subcode/Explanation | Relevant Theory/Literature |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1—Construction industry in developing countries; culture and organizations | Perception of “culture and behaviour” |

| Culture in organizations and behaviour, reflecting on what emerges and what is relevant |

| Perception of “construction industry in developing countries” |

| Construction industry in developing countries | |

| Smallness |

| The size of the country and the firms and how size reflects on management and change policy | |

| Perception of owners/managers |

| Small business and construction industry literature, reflecting on what emerges and what is relevant | |

| Perception of business by owners/managers |

| Same as above | |

| Perceived barriers |

| The main characteristics of the construction industry in developing countries and in North Cyprus and whether this is relevant to the barriers faced by the industry. The characteristics of small firms in the literature, reflecting on what emerges and what is relevant. | |

| 2—Construction in North Cyprus; trauma-affected businesses | Perceived politics |

| Literature on trauma; reflecting on what emerges and what is relevant |

| History |

| Construction industry in North Cyprus and history of the country. Literature on history and de facto states and trauma; reflecting on what emerges and what is relevant | |

| Perception of project management | |||

| Current political status of North Cyprus |

| Same as above | |

| External environment |

| Same as above | |

| Discussion 3—Resilience | Resilient behaviour |

| Literature on resilience and relationships |

| Adaptive changes in the company |

| Literature on organizational resilience and complex theory; reflecting on what emerges and what is relevant | |

| The amount of disturbance to the industry |

| Literature on history, de facto states and trauma, and the adaptive cycle; reflecting on what emerges and what is relevant | |

| Unstable environment in the industry |

| Same as above | |

| Reaction to the unstable environment |

| The literature on memory, trust and remembrance, and how it is relevant to the behaviour of the owners/managers |

Appendix C. Subthemes

Table A3.

Sample extracts for main theme 1 and its subthemes.

Table A3.

Sample extracts for main theme 1 and its subthemes.

| Theme 1 | Characteristics of the Sociopolitical Environment | |

|---|---|---|

| Subthemes | Small Country | Company |

| Examples of coded text segments | “Unfortunately, North Cyprus is too small to have a corporate and a bigger structure.” “Unfortunately, because the budget of North Cyprus is very limited, and the size of the projects is too small, even if we want to provide training and know that such training is necessary, we cannot include the cost of training in our budget.” | D |

| “We can have partnerships with other companies. I am not sure what the future will show us but there are company mergers in Europe. Companies come together for some bigger projects. But this is a small country and there hasn’t been anything like that yet.” | G | |

| “Cyprus is a small place. You cannot get bigger here.” | A | |

| “We are a small island … in the islands when everybody tries to do the same thing we face a saturated market.” | E | |

| “The capacity of our companies is obvious [referring to limited capacity]” | K | |

| History and Culture | ||

| “I can give you an example from myself … until ’74 we used to work individually … we used to construct road with our own facilities … the measurement … that period’s conditions were different and today’s measurements are different … in that period there weren’t any projects that required engineers, contractors … after ’74 with the improvement of the country it became more professional --.” “… it changed after ’74 … we maintained our patterns until ’74 … after ’74 it started to change … also our lifestyle … maybe we couldn’t change ourselves because of the things we experienced in those years … there are also lots of sociological reasons … the conditions weren’t suitable … the movement started after ’74” | F | |

| Patron Country and External Agencies | ||

| “We prepared ourselves believing that we’ll improve more… but in the last 2–3 years we saw that there is a different approach, different direction … with the cooperation of TC [Turkish Republic] and North Cyprus government… they put a barrier in front of this country’s businessmen, investors … we see that they don’t want them to improve, gain power, go forward… and we are falling down from the point where we are now …” “the Turkish Republic [Turkey] didn’t give any opportunities to our contractors… they still don’t give the opportunity and that time they never gave the opportunity” | C | |

| “If the tenders of Turkish projects [funded projects by Turkey] were available here, I would tell you where I would be as a company [referring to future and blaming Turkey].” | E | |

| “I mean, everyone is complaining… contractors etc… Because they crushed us… with the European Union [referring to the payment strategy and arbitration policies of EU in North Cyprus]… what should I say.” | H | |

| “We anticipated that the Annan-plan would work and made big investments.” | B | |

| Uncertainty and non-recognition | ||

| “Sincerely, I can’t predict where it will be. I can’t predict what will happen tomorrow or the following day in this country. Really, erm, because the countries determine targets according to their socio-economic politics.” “Whoever you chat with about company management, he will mention the Cyprus problem and the social problem… because this a part of daily life… it is always with us.” | E | |

| “They [Turkey] tried to weaken the economy here, and there existed the politics forcing us to say ‘yes’ to the Annan Plan.” | K | |

| “We revitalized ourselves over the past 25–30 years, seeing the potential in our country [more opportunities in construction]… and considering that maybe one day this country will be recognized so we can do projects abroad… we prepared ourselves as if we were going to operate internationally… with saying this year… this year… we stopped at the highest point… we waited for that process… but unfortunately now… instead of going forward we’re drawing back… this is the point that we’ve reached.” | C | |

Table A4.

Sample extracts for main theme 2 and its subthemes.

Table A4.

Sample extracts for main theme 2 and its subthemes.

| Theme 2 | Emotional Experience of the Owners/Managers | |

|---|---|---|

| Subtheme | Feeling Socially Marginalized | Company |

| Examples of coded text segments | “All of them are financed by Turkey. All of the investment tenders… investment projects… those were in TRNC… were financed by Turkey. I mean, they [North Cyprus Government] do not even fund to pay their officers, how could they finance projects? I mean investment budgets are provided by Turkey.”“Turkish people from Cyprus don’t have the opportunity to do business apart from their territory. I mean how … Their qualifications are not accepted; their company is not accepted because you are not accepted as a country. Unknown, illegal -- you are an unknown, illegal country. If I go to Germany as a company they will look at me laughing. It will be considered very funny” | H |

| “There is a difference between when an elephant falls and a mouse falls… a mouse will get up immediately… an elephant doesn’t fall easily but doesn’t get up easily… because our companies are small we can only save ourselves for a short time… next year especially the number of infrastructure companies will significantly decrease… the ones that remain will have big problems.” | K | |

| “There is no light on the horizon. Everything is granted to Turkey.” | H | |

| “Because we are not the strong side [North Cyprus contractors]. You need to live so you want a job, you also have to make your employees live. But your opponent is strong [contractors from Turkey].” | G | |

| Helplessness | ||

| “On the other hand, there is money that comes from Turkey for the infrastructure and they are trying to give this to their own contractors… the tenders are opened in Ankara [capital of Turkey]… for that reason I can’t tell you anything about the future.” | D | |

| “I mean, everyone is complaining… contractors etc… Because they crushed us…” | H | |

| “They [Turkey] tried to weaken the economy here, and there existed the politics which forced us to say ‘yes’ to the Annan Plan… the departure of the ‘Ulusal Birlik Partisi’ [the governing political party at the time] from the government in 2000… with Turkey reacting by decreasing its economical help and not opening tenders in construction… creating chaos here.” | K | |

| Hopelessness | ||

| “We could have opened ourselves to the world and improved our capacity for any kind of project… but unfortunately, we weren’t given this opportunity… so we can’t know what our company’s position will be in 10 years… not even in 5 years… we don’t know.”“The Turkish Cypriot community will disappear slowly… they don’t want us to gain economic power… so the Turkish Cypriot population will be alienated… the Turkish Cypriot community will be differentiated…I don’t have any expectations at all.” | C | |

| “(laughing) It hasn’t changed for all these years and it won’t change … there is no intention for changes.” | A | |

| “If this situation goes on, then only one or two companies will remain in infrastructure in North Cyprus in a few years… I mean that’s what I predict. If someone wants to buy my asphalt plant, I would sell.” | D | |

| “As I said… we can’t see our future… we see the next year as dark… for example, next year what kind of investments are there in this country, what kinds of tenders will be opened? We don’t have any idea.” | E | |

References

- Horne, J.F.; Orr, J.E. Assessing behaviours that create resilient organizations. Employ. Relat. Today 1997, 24, 29–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazzocchi, F. Complexity in biology: Exceeding the limits of reductionism and determinism using complexity theory. EMBO Rep. 2008, 9, 10–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carpenter, S.; Walker, B.; Anderies, J.M.; Abel, N. From metaphor to measurement: Resilience of what to what? Ecosystems 2001, 4, 765–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prigogine, I. The End of Certainty: Time, Chaos, and the New Laws of Nature; Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Herbane, B. Small business research: Time for a crisis-based view. Int. Small Bus. J. 2010, 28, 43–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Runyan, R.C. Small business in the face of crisis: Identifying barriers to recovery from a natural disaster. J. Contingencies Crisis Manag. 2006, 14, 12–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sullivan-Taylor, B.; Branicki, L. Creating resilient SMEs: Why one size might not fit all. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2011, 49, 5565–5579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wedawatta, G.; Ingirige, B.; Amaratunga, D. Building up the resilience of construction sector SMEs and their supply chains to extreme weather events. Int. J. Strateg. Prop. Manag. 2010, 14, 362–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofstede, G. Motivation, leadership, and organization: Do American theories apply abroad? Organ. Dyn. 1980, 9, 42–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofstede, G. Cultural constraints in management theories. Acad. Manag. Exec. 1993, 7, 81–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghobadian, A.; Gallear, D. TQM and Organisation size. Int. J. Oper. Prod. Manag. 1996, 17, 121–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saad, M.H.; Hagelaar, G.; van der Velde, G.; Omta, S.W. Conceptualization of SMEs’ business resilience: A systematic literature review. Cogent Bus. Manag. 2021, 8, 1938347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sapeciay, Z.; Wilkinson, S.; Costello, S.B. Building organisational resilience for the construction industry: New Zealand practitioners’ perspective. Int. J. Disaster Resil. Built Environ. 2017, 8, 98–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linnenluecke, M.K. Resilience in business and management research: A review of influential publications and a research agenda. Int. J. Manag. Rev. 2017, 19, 4–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz-Martin, C.; López-Paredes, A.; Wainer, G. What we know and do not know about organizational resilience. Int. J. Prod. Manag. Eng. 2018, 6, 11–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, K.; Shleifer, A.; Vishy, W.R. Why is Rent-Seeking So Costly to Growth? AEA Pap. Proceeding 1993, 83, 409–414. [Google Scholar]

- Tamkoç, M. The Turkish Cypriot State: The Embodiment of the Right of Self-Determination; K. Rustem & Brothers: London, UK, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Diez, T.; Tocci, N. (Eds.) Cyprus: A Conflict at the Crossroads. Manchester University Press: Manchester, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Lacher, H.; Kaymak, E. Transforming identities: Beyond the politics of non-settlement in North Cyprus. Mediterr. Politics 2006, 10, 147–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olgun, E. Cyprus: A new and realistic approach. J. Int. Aff. 1999, 4, 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Özyiğit, A.; Eminer, F. De-facto States and Aid Dependence. Uluslararası İlişkiler/Int. Relat. 2021, 18, 51–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lynch, D. Engaging Eurasia’s Separatist States: Unresolved Conflicts and De-Facto State; United States Institute of Peace: Washington, DC, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Ulas, H. Donors and De Facto States: A Case Study of Un Peacebuilding in the Self-Declared Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus. J. Peacebuilding Dev. 2016, 11, 75–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pegg, S. International Society and the De Facto State; Ashgate Publishing Limited: Farnham, UK, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Annan, K. The Comprehensive Settlement of the Cyprus Problem; UN Official Paper; UN Headquarters: New York, NY, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Simmering Tensions Over a Divided Island. Available online: https://www.gisreportsonline.com/r/divided-cyprus/ (accessed on 20 March 2023).

- Baldacchino, G.; Milne, D. Lessons from the Political Economy of Small Islands: The Resourcefulness of Jurisdiction; St. Martin’s Press: New York, NY, USA; Institute of Island Studies: London, UK, 2000. [Google Scholar]