The Influence of Internet-Specific Epistemic Beliefs on Academic Achievement in an Online Collaborative Learning Context for College Students

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Framework

2.1. Integrated Model of Epistemic Beliefs and Self-Regulated Learning

2.2. The Relationship between Internet-Specific Epistemic Beliefs and Academic Achievement

2.3. The Mediating Effect of Metacognitive Strategies in Internet-Specific Epistemic Beliefs and Academic Achievement in Online Collaborative Learning

2.4. Mediating Effects of Achievement Goal Orientation in Internet-Specific Epistemic Beliefs and Online Collaborative Learning Academic Achievement

2.5. Chain Mediating Effects of Achievement Goal Orientation and Metacognitive Strategies in Internet-Specific Epistemic Beliefs and Online Collaborative Learning Academic Achievement

2.6. Hypotheses

3. Methodology

3.1. Research Context

3.2. Instruments

3.2.1. Internet-Specific Epistemic Beliefs Questionnaire

3.2.2. Metacognitive Strategy Questionnaire

3.2.3. Achievement Goal Orientation Questionnaire

3.2.4. Academic Achievement Questionnaire

3.2.5. Data Collection and Analysis

4. Results

4.1. Common Method Bias and Multicollinearity Tests

4.2. Descriptive Statistics and Correlation among Variables

4.3. Analysis of Measurement Models

4.3.1. Reliability and Convergent Validity

4.3.2. Discriminant Validity

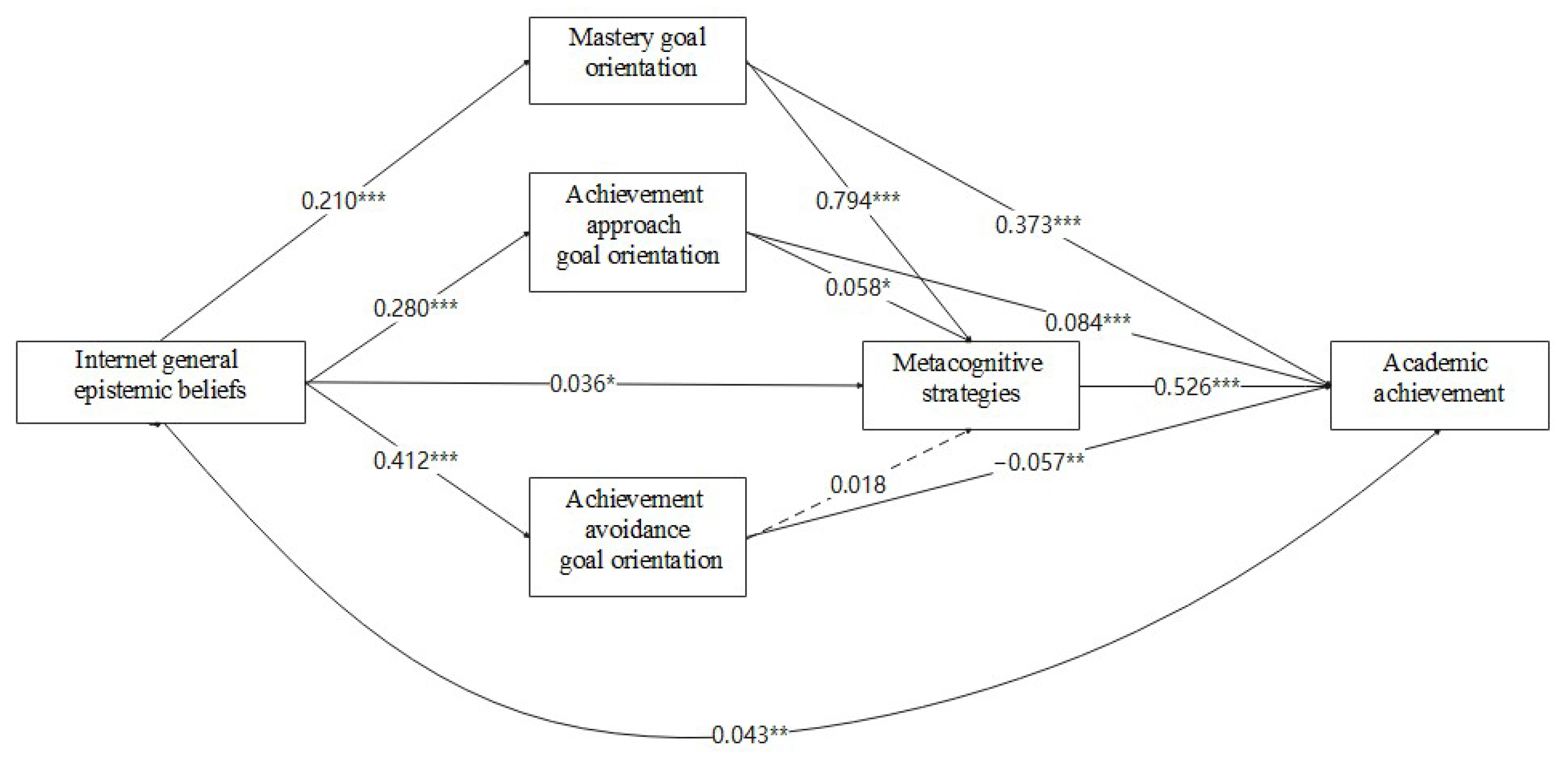

4.4. Direct Effect Analysis

4.5. Multiple Mediation Effects of Internet-Specific Epistemic Beliefs on College Students’ Academic Achievement

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions, Limitations, and Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Academic Achievement Questionnaire

- When I encountered difficulties in online collaborative learning, I persisted in overcoming them to complete the learning tasks.

- In online collaborative learning, I work overtime to complete my tasks on time.

- I put forth a high level of effort in online collaborative learning.

- The quality of my learning situation is high in online collaborative learning.

- In online collaborative learning, I complete the learning tasks that meet the teacher’s requirements.

- In online collaborative learning, I actively seek out challenging learning tasks.

- In online collaborative learning, I take the initiative to solve problems in learning.

References

- Ofori, F.; Maina, E.; Gitonga, R. Using machine learning algorithms to predict students’ performance and improve learning outcome: A literature based review. J. Inf. Technol. 2020, 4, 33–55. [Google Scholar]

- Qureshi, M.A.; Khaskheli, A.; Qureshi, J.A.; Raza, S.A.; Yousufi, S.Q. Factors affecting students’ learning performance through collaborative learning and engagement. Interact. Learn. Environ. 2021, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadwin, A.F.; Järvelä, S.; Miller, M. Self-regulation, co-regulation, and shared regulation in collaborative learning environments. In Handbook of Self-Regulation of Learning and Performance; Schunk, D., Greene, J.A., Eds.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2018; pp. 83–106. [Google Scholar]

- Ally, M. Foundations of educational theory for online learning. Theory Pract. Online Learn. 2004, 2, 15–44. [Google Scholar]

- Järvelä, S.; Malmberg, J.; Koivuniemi, M. Recognizing socially shared regulation by using the temporal sequences of online chat and logs in CSCL. Learn. Instr. 2016, 42, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, P.M.; Chan, J.K.; Lit, K.K. Student learning performance in online collaborative learning. Educ. Inf. Technol. 2022, 27, 8129–8145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiu, Y.L.; Liang, J.C.; Tsai, C.C. Internet-specific epistemic beliefs and self-regulated learning in online academic information searching. Metacogn. Learn. 2013, 8, 235–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadegaridehkordi, E.; Shuib, L.; Nilashi, M.; Asadi, S. Decision to adopt online collaborative learning tools in higher education: A case of top Malaysian universities. Educ. Inf. Technol. 2019, 24, 79–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volet, S.; Summers, M.; Thurman, J. High-level co-regulation in collaborative learning: How does it emerge and how is it sustained? Learn. Instr. 2009, 19, 128–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, C.K. Co-regulation of learning in computer-supported collaborative learning environments: A discussion. Metacogn. Learn. 2012, 7, 63–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saab, N. Team regulation, regulation of social activities or co-regulation: Different labels for effective regulation of learning in CSCL. Metacogn. Learn. 2012, 7, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muis, K.R. The role of epistemic beliefs in self-regulated learning. Educ. Psychol. 2007, 42, 173–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmerman, B.J. A social cognitive view of self-regulated academic learning. J. Educ. Psychol. 1989, 81, 329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pintrich, P.R. The role of goal orientation in self-regulated learning. In Handbook of Self-Regulation; Boekaerts, M., Pintrich, P.R., Zeidner, M., Eds.; Academic Press: San Diego, CA, USA, 2000; pp. 452–502. [Google Scholar]

- Zimmerman, B.J. Attaining self-regulation: A social cognitive perspective. In Handbook of Self-Regulation; Boekaerts, M., Pintrich, P.R., Zeidner, M., Eds.; Academic Press: San Diego, CA, USA, 2000; pp. 13–40. [Google Scholar]

- Winne, P.H.; Hadwin, A.F. Studying as self-regulated learning. In Metacognition in Educational Theory and Practice; Hacker, D.J., Dunlosky, J., Graesser, A.C., Eds.; Erlbaum: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 1998; pp. 277–304. [Google Scholar]

- Hofer, B.K.; Pintrich, P.R. The development of epistemological theories: Beliefs about knowledge and knowing and their relation to learning. Rev. Educ. Res. 1997, 67, 88–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofer, B.K. Introduction: Paradigmatic approaches to personal epistemology. Educ. Psychol. 2004, 39, 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buehl, M.M.; Alexander, P.A.; Murphy, P.K. Beliefs about schooled knowledge: Domain specific or domain general? Contemp. Educ. Psychol. 2002, 27, 415–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bråten, I.; StrØmsØ, H.I.; Samuelstuen, M.S. The relationship between Internet-specific epistemological beliefs and learning within Internet technologies. J. Educ. Comput. Res. 2005, 33, 141–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, C.C. Relationships between student scientific epistemological beliefs and perceptions of constructivist learning environments. Educ. Res. 2000, 42, 193–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofer, B.K. Personal epistemology research: Implications for learning and teaching. Educ. Psychol. Rev. 2001, 13, 353–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulyshen, T.Z.; Koehler, M.J.; Gao, F. Understanding the connection between epistemic beliefs and Internet searching. J. Educ. Comput. Res. 2015, 53, 345–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schommer, M.; Calvert, C.; Gariglietti, G.; Bajaj, A. The development of epistemological beliefs among secondary students: A longitudinal study. J. Educ. Psychol. 1997, 89, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noroozi, O. The role of students’ epistemic beliefs for their argumentation performance in higher education. Innov. Educ. Teach. Int. 2022, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mason, L.; Boscolo, P.; Tornatora, M.C.; Ronconi, L. Besides knowledge: A cross-sectional study on the relations between epistemic beliefs, achievement goals, self-beliefs, and achievement in science. Instr. Sci. 2013, 41, 49–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pintrich, P.; Smith, D.; Garcia, T.; McKeachie, W. A manual for the use of the motivated strategies for learning Questionnaire (MSLQ). Coll. Stud. 1991, 48109, 76. [Google Scholar]

- O’malley, J.M.; O’Malley, M.J.; Chamot, A.U. Learning Strategies in Second Language Acquisition; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1990; pp. 120–125. [Google Scholar]

- Broadbent, J.; Poon, W.L. Self-regulated learning strategies & academic achievement in online higher education learning environments: A systematic review. Internet High. Educ. 2015, 27, 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Muis, K.R.; Franco, G.M. Epistemic beliefs: Setting the standards for self-regulated learning. Contemp. Educ. Psychol. 2009, 34, 306–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghiasvand, M.Y. Relationship between learning strategies and academic achievement; based on information processing approach. Procedia-Soc. Behav. Sci. 2010, 5, 1033–1036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, M.M. Enhancing web-based language learning through self-monitoring. J. Comput. Assist. Learn. 2007, 23, 187–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carson, A.D. Predicting student success from the LASSI for learning online (LLO). J. Educ. Comput. Res. 2011, 45, 399–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahl, T.I.; Bals, M.; Turi, A.L. Are students’ beliefs about knowledge and learning associated with their reported use of learning strategies? Br. J. Educ. Psychol. 2005, 75, 257–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strømsø, H.I.; Bråten, I. The role of personal epistemology in the self-regulation of internet-based learning. Metacogn. Learn. 2010, 5, 91–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schommer-Aikins, M.; Hutter, R. Epistemological beliefs and thinking about everyday controversial issues. J. Psychol. 2002, 136, 5–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schommer, M. Effects of beliefs about the nature of knowledge on comprehension. J. Educ. Psychol. 1990, 82, 498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schommer, M.; Crouse, A.; Rhodes, N. Epistemological beliefs and mathematical text comprehension: Believing it is simple does not make it so. J. Educ. Psychol. 1992, 84, 435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Midgley, C.; Kaplan, A.; Middleton, M. Performance-approach goals: Good for what, for whom, under what circumstances, and at what cost? J. Educ. Psychol. 2001, 93, 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elliot, A.J.; Church, M.A. A hierarchical model of approach and avoidance achievement motivation. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1997, 72, 218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, X.; Wang, C.H. Achievement goal orientations and self-regulated learning strategies of adult and traditional learners. New Horiz. Adult Educ. Hum. Resour. Dev. 2018, 30, 5–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Sang, Q.; Ge, M. A study on the relationship between independent learning, achievement goal orientation and academic achievement among college students. Psychol. Sci. 2010, 194–197. Available online: https://kns.cnki.net/kcms2/article/abstract?v=3uoqIhG8C44YLTlOAiTRKgchrJ08w1e7_IFawAif0mxdGbXb9C2CRcjztPK2-nuxMVEOHC9ut-WpI7OguzxEcgVmrR4OnUYY&uniplatform=NZKPT (accessed on 31 May 2023). [CrossRef]

- Madjar, N.; Weinstock, M.; Kaplan, A. Epistemic beliefs and achievement goal orientations: Relations between constructs versus personal profiles. J. Educ. Res. 2017, 110, 32–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winberg, T.M.; Hofverberg, A.; Lindfors, M. Relationships between epistemic beliefs and achievement goals: Developmental trends over grades 5–11. Eur. J. Psychol. Educ. 2019, 34, 295–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, K.W.; Wong, K.Y.A.; Lo, E.S.C. Relational analysis of intrinsic motivation, achievement goals, learning strategies and academic achievement for Hong Kong secondary students. Asia-Pac. Educ. Res. 2012, 21, 230–243. [Google Scholar]

- Somuncuoglu, Y.; Yildirim, A. Relationship between achievement goal orientations and use of learning strategies. J. Educ. Res. 1999, 92, 267–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alismaiel, O.A.; Cifuentes-Faura, J.; Al-Rahmi, W.M. Online Learning, Mobile Learning, and Social Media Technologies: An Empirical Study on Constructivism Theory during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Sustainability 2022, 14, 11134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cifuentes-Faura, J.; Obor, D.O.; To, L.; Al-Naabi, I. Cross-Cultural Impacts of COVID-19 on Higher Education Learning and Teaching Practices in Spain, Oman, Nigeria and Cambodia: A Cross-Cultural Study. J. Univ. Teach. Learn. Pract. 2021, 18, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiu, Y.L.; Liang, J.C.; Tsai, C.C. Exploring the roles of education and Internet search experience in students’ Internet-specific epistemic beliefs. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2016, 62, 286–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kammerer, Y.; Amann, D.G.; Gerjets, P. When adults without university education search the Internet for health information: The roles of Internet-specific epistemic beliefs and a source evaluation intervention. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2015, 48, 297–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puzziferro, M. Online technologies self-efficacy and self-regulated learning as predictors of final grade and satisfaction in college-level online courses. Am. J. Distance Educ. 2008, 22, 72–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pintrich, P.R.; Smith, D.A.; Garcia, T.; McKeachie, W.J. Reliability and predictive validity of the Motivated Strategies for Learning Questionnaire (MSLQ). Educ. Psychol. Meas. 1993, 53, 801–813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Lee, J.Y.; Podsakoff, N.P. Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J. Appl. Psychol. 2003, 88, 879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’brien, R.M. A caution regarding rules of thumb for variance inflation factors. Qual. Quant. 2007, 41, 673–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F., Jr.; Hult, G.T.M.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. A Primer on Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM); Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Preacher, K.J.; Hayes, A.F. SPSS and SAS procedures for estimating indirect effects in simple mediation models. Behav. Res. Methods Instrum. Comput. 2004, 36, 717–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conley, A.M.; Pintrich, P.R.; Vekiri, I.; Harrison, D. Changes in epistemological beliefs in elementary science students. Contemp. Educ. Psychol. 2004, 29, 186–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cano, F. Epistemological beliefs and approaches to learning: Their change through secondary school and their influence on academic performance. Br. J. Educ. Psychol. 2005, 75, 203–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Li, X.; Zhang, Y.; Li, X. The effects of a group awareness tool on knowledge construction in computer-supported collaborative learning. Br. J. Educ. Technol. 2021, 52, 1178–1196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kardash, C.M.; Howell, K.L. Effects of epistemological beliefs and topic-specific beliefs on undergraduates’ cognitive and strategic processing of dual-positional text. J. Educ. Psychol. 2000, 92, 524–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, K. Hong Kong teacher education students’ epistemological beliefs and approaches to learning. Res. Educ. 2003, 69, 36–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.H.; Shannon, D.M.; Ross, M.E. Students’ characteristics, self-regulated learning, technology self-efficacy, and course outcomes in online learning. Distance Educ. 2013, 34, 302–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hau, K.T.; Salili, F. Achievement goals and causal attributions of Chinese students. In Growing Up the Chinese Way: Chinese Child and Adolescent Development; Lau, S., Ed.; The Chinese University Press: Hong Kong, China, 1996; pp. 121–145. [Google Scholar]

- Maehr, M.L.; Midgley, C. Enhancing student motivation: A schoolwide approach. Educ. Psychol. 1991, 26, 399–427. [Google Scholar]

- Otu, M.N.; Ehiane, S.O.; Maapola-Thobejane, H.; Olumoye, M.Y. Psychosocial Implications, Students Integration/Attrition, and Online Teaching and Learning in South Africa’s Higher Education Institutions in the Context of COVID-19. Sustainability 2023, 15, 6351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osipov, P.N.; Ziyatdinova, J.N. Collaborative learning: Pluses and problems. In Proceedings of the 2015 International Conference on Interactive Collaborative Learning (ICL), Firenze, Italy, 20–24 September 2015; pp. 361–364. [Google Scholar]

| Variables | M | SD | Relevance | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | |||

| GEN | 4.417 | 1.322 | -- | ||||||

| JUS | 5.456 | 0.896 | 0.272 ** | -- | |||||

| MAS | 5.365 | 0.873 | 0.319 ** | 0.772 ** | -- | ||||

| APP | 5.040 | 1.113 | 0.332 ** | 0.377 ** | 0.421 ** | -- | |||

| AVO | 4.999 | 1.154 | 0.472 ** | 0.251 ** | 0.273 ** | 0.582 ** | -- | ||

| MET | 5.305 | 0.866 | 0.347 ** | 0.825 ** | 0.855 ** | 0.443 ** | 0.312 ** | -- | |

| ACH | 5.256 | 0.873 | 0.364 ** | 0.833 ** | 0.864 ** | 0.472 ** | 0.281 ** | 0.886 ** | -- |

| Structure Variables | Measurement Variables | Standard Factor Loadings | AVE | CR | Alpha Coefficient |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GEN | GEN1 | 0.717 | 0.565 | 0.886 | 0.874 |

| GEN2 | 0.827 | ||||

| GEN3 | 0.680 | ||||

| GEN4 | 0.777 | ||||

| GEN5 | 0.754 | ||||

| GEN6 | 0.747 | ||||

| JUS | JUS1 | 0.623 | 0.565 | 0.837 | 0.843 |

| JUS2 | 0.786 | ||||

| JUS3 | 0.752 | ||||

| JUS4 | 0.830 | ||||

| MAS | MAS1 | 0.735 | 0.519 | 0.812 | 0.809 |

| MAS2 | 0.726 | ||||

| MAS3 | 0.744 | ||||

| MAS4 | 0.673 | ||||

| APP | APP1 | 0.756 | 0.627 | 0.834 | 0.832 |

| APP2 | 0.784 | ||||

| APP3 | 0.834 | ||||

| AVO | AVO1 | 0.786 | 0.581 | 0.806 | 0.801 |

| AVO2 | 0.715 | ||||

| AVO3 | 0.783 | ||||

| MET | MET1 | 0.804 | 0.558 | 0.910 | 0.911 |

| MET2 | 0.711 | ||||

| MET3 | 0.741 | ||||

| MET4 | 0.751 | ||||

| MET5 | 0.779 | ||||

| MET6 | 0.745 | ||||

| MET7 | 0.709 | ||||

| MET8 | 0.731 | ||||

| ACH | ACH1 | 0.778 | 0.538 | 0.890 | 0.891 |

| ACH2 | 0.668 | ||||

| ACH3 | 0.672 | ||||

| ACH4 | 0.757 | ||||

| ACH5 | 0.722 | ||||

| ACH6 | 0.775 | ||||

| ACH7 | 0.756 |

| Number | Models | χ2 | df | χ2/df | IFI | TLI | CFI | RMSEA | SRMR | Model Comparison | Δχ2 | Δdf |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Seven-factor model | 1549.033 | 529 | 2.928 | 0.912 | 0.901 | 0.912 | 0.062 | 0.0510 | |||

| 2 | Six-factor model | 2118.041 | 535 | 3.959 | 0.864 | 0.848 | 0.863 | 0.077 | 0.0701 | 2 vs. 1 | 569.008 *** | 6 |

| 3 | Five-factor model | 2163.03 | 540 | 4.006 | 0.860 | 0.845 | 0.86 | 0.077 | 0.0724 | 3 vs. 1 | 613.997 *** | 11 |

| 4 | Four-factor model | 2682.546 | 544 | 4.931 | 0.816 | 0.798 | 0.815 | 0.088 | 0.0881 | 4 vs. 1 | 1133.513 *** | 15 |

| 5 | Three-factor model | 2692.555 | 547 | 4.922 | 0.815 | 0.798 | 0.815 | 0.088 | 0.0884 | 5 vs. 1 | 1143.522 *** | 18 |

| 6 | Two-factor model | 2692.273 | 548 | 4.913 | 0.815 | 0.799 | 0.815 | 0.088 | 0.0886 | 6 vs. 1 | 1143.24 *** | 19 |

| 7 | One-factor model | 3597.989 | 549 | 6.554 | 0.738 | 0.714 | 0.736 | 0.105 | 0.1073 | 7 vs. 1 | 2048.956 *** | 20 |

| Variables | MAS | APP | AVO | MET | ACH | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | Model 5 | Model 6 | Model 7 | Model 8 | |

| Grade | −0.021 | −0.023 | 0.040 | −0.023 | −0.034 | −0.009 | −0.016 | −0.006 |

| Age | −0.042 | 0.036 | −0.016 | −0.031 | −0.003 | −0.019 | 0.010 | 0.009 |

| Gender | −0.046 | −0.017 | 0.041 | −0.008 | −0.002 | 0.061 | 0.060 | 0.038 |

| Specialty | 0.081 | −0.031 | −0.158 | 0.049 | −0.018 | 0.032 | −0.043 | −0.018 |

| GEN | 0.077 *** | 0.206 *** | 0.388 *** | 0.088 *** | -- | 0.103 *** | -- | -- |

| JUS | 0.711 *** | 0.386 *** | 0.170 ** | 0.754 *** | -- | 0.770 *** | -- | -- |

| MAS | -- | -- | -- | -- | 0.799 *** | -- | 0.815 *** | -- |

| APP | -- | -- | -- | -- | 0.059 * | -- | 0.115 *** | -- |

| AVO | -- | -- | -- | -- | 0.035 | -- | −0.020 | -- |

| MET | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | 0.897 *** |

| R2 | 0.618 | 0.200 | 0.248 | 0.701 | 0.743 | 0.716 | 0.763 | 0.787 |

| Adj.R2 | 0.613 | 0.190 | 0.239 | 0.697 | 0.739 | 0.712 | 0.760 | 0.784 |

| R2 Amount of change | 0.568 | 0.189 | 0.236 | 0.656 | 0.698 | 0.685 | 0.733 | 0.756 |

| F-value | 133.624 *** | 20.674 *** | 27.279 *** | 193.716 *** | 204.360 *** | 208.254 *** | 228.151 *** | 366.250 *** |

| Intermediary Effect | Effect Type | Effect Path | Effect | Boot SE | Effect Amount (%) | Boot LLCI | Boot ULCI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GEN → ACH | Direct effect | GEN → ACH | 0.043 | 0.014 | 17.92 | 0.015 | 0.070 |

| Intermediary effect | MAS | 0.079 | 0.015 | 32.92 | 0.051 | 0.111 | |

| APP | 0.023 | 0.007 | 9.58 | 0.010 | 0.039 | ||

| AVO | −0.024 | 0.010 | 10.00 | −0.045 | −0.004 | ||

| MET | 0.019 | 0.011 | 7.92 | −0.002 | 0.040 | ||

| MAS → MET | 0.088 | 0.015 | 36.67 | 0.060 | 0.119 | ||

| APP → MET | 0.008 | 0.005 | 3.33 | 0.000 | 0.019 | ||

| AVO → MET | 0.004 | 0.006 | 1.67 | −0.008 | 0.017 | ||

| GEN → ACH | 0.197 | 0.029 | 82.08 | 0.140 | 0.257 | ||

| Total effect | GEN →ACH | 0.240 | 0.027 | 100.0 | 0.186 | 0.294 | |

| JUS → ACH | Direct effect | JUS → ACH | 0.240 | 0.031 | 29.59 | 0.180 | 0.300 |

| Intermediary effect | MAS | 0.238 | 0.032 | 29.35 | 0.173 | 0.303 | |

| APP | 0.038 | 0.012 | 4.69 | 0.017 | 0.065 | ||

| AVO | −0.011 | 0.007 | 1.36 | −0.027 | 0.002 | ||

| MET | 0.147 | 0.025 | 18.13 | 0.100 | 0.200 | ||

| MAS → MET | 0.148 | 0.025 | 18.25 | 0.103 | 0.201 | ||

| APP → MET | 0.007 | 0.005 | 0.86 | −0.001 | 0.018 | ||

| AVO → MET | 0.004 | 0.003 | 0.49 | −0.001 | 0.011 | ||

| JUS → ACH | 0.571 | 0.034 | 70.41 | 0.508 | 0.640 | ||

| Total effect | JUS → ACH | 0.811 | 0.024 | 100.0 | 0.764 | 0.859 |

| Hypotheses | Results |

|---|---|

| Hypothesis 1. In online collaborative learning environments, college students’ Internet general epistemic beliefs (H1A) and college students’ Internet-specific epistemic justification (H1a) significantly and positively affect college students’ academic achievement. | Established |

| Hypothesis 2. Metacognitive strategies of college students in online collaborative learning environments significantly and positively affect college students’ academic achievement. | Established |

| Hypothesis 3. In online collaborative learning environments, college students’ Internet general epistemic beliefs (H3A) and college students’ Internet-specific epistemic justification (H3a) significantly and positively influence college students’ metacognitive strategies. | Established |

| Hypothesis 4. In online collaborative learning environments, college students’ Internet general epistemic beliefs (H4A) and college students’ Internet-specific epistemic justification (H4a) have a significant positive effect on college students’ academic achievement through their metacognitive strategies. | H4a was established |

| Hypothesis 5. In online collaborative learning environments, college students’ Internet general epistemic beliefs and Internet-specific epistemic justification significantly and positively influenced college students’ mastery goal orientation (H5A, H5a), achievement approach goal orientation (H5B, H5b), and achievement avoidance goal orientation (H5C, H5c). | Established |

| Hypothesis 6. In online collaborative learning environments, college students’ mastery goal orientation (H6A), achievement approach goal orientation (H6B), and achievement avoidance goal orientation (H6C) significantly and positively affect college students’ academic achievement. | H6A, H6B were established |

| Hypothesis 7. In online collaborative learning environments, college students’ Internet general epistemic beliefs and Internet-specific epistemic justification proved to have a significant positive effect on college students’ academic achievement through their mastery goal orientation (H7A, H7a), achievement approach goal orientation (H7B, H7b), and achievement avoidance goal orientation (H7C, H7c). | H7A, H7B, H7a, H7b were established |

| Hypothesis 8. Mastery goal orientation (H8A), achievement approach goal orientation (H8B), and achievement avoidance goal orientation (H8C) significantly and positively influenced college students’ metacognitive strategies in an online collaborative learning environment. | H8A, H8B were established |

| Hypothesis 9. Mastery goal orientation (H9A, H9a), achievement approach goal orientation (H9B, H9b), achievement avoidance goal orientation (H9C, H9c), and college students’ metacognitive strategies play a chain mediating role in the relationship between college students’ general Internet-specific epistemic beliefs, Internet-specific epistemic justification, and college students’ academic achievement in an online collaborative learning environment. | H9A, H9a were established |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Liang, Y.; Ren, L.; Wei, C.; Shi, Y. The Influence of Internet-Specific Epistemic Beliefs on Academic Achievement in an Online Collaborative Learning Context for College Students. Sustainability 2023, 15, 8938. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15118938

Liang Y, Ren L, Wei C, Shi Y. The Influence of Internet-Specific Epistemic Beliefs on Academic Achievement in an Online Collaborative Learning Context for College Students. Sustainability. 2023; 15(11):8938. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15118938

Chicago/Turabian StyleLiang, Yunzhen, Liling Ren, Chun Wei, and Yafei Shi. 2023. "The Influence of Internet-Specific Epistemic Beliefs on Academic Achievement in an Online Collaborative Learning Context for College Students" Sustainability 15, no. 11: 8938. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15118938

APA StyleLiang, Y., Ren, L., Wei, C., & Shi, Y. (2023). The Influence of Internet-Specific Epistemic Beliefs on Academic Achievement in an Online Collaborative Learning Context for College Students. Sustainability, 15(11), 8938. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15118938