Early Stages of the Fablab Movement: A New Path for an Open Innovation Model

Abstract

1. Introduction

- Knowledge has turned into another product that can become an active subject for negotiation.

- The cost associated with knowledge gain and transfer has been drastically reduced, thanks to the advances in the information and communication technologies.

- The interconnectivity level between the agents involved in the generation and knowledge management has increased in an exacerbated manner.

1.1. The Concept of Innovation

- Innovation derived from science (technology push).

- Innovation derived from market requirements (demand driven).

- Innovation derived from connections between market players.

- Innovation derived from technological networks.

- Innovation derived from social networks.

1.2. Open Innovation

1.3. FabLab and Innovation

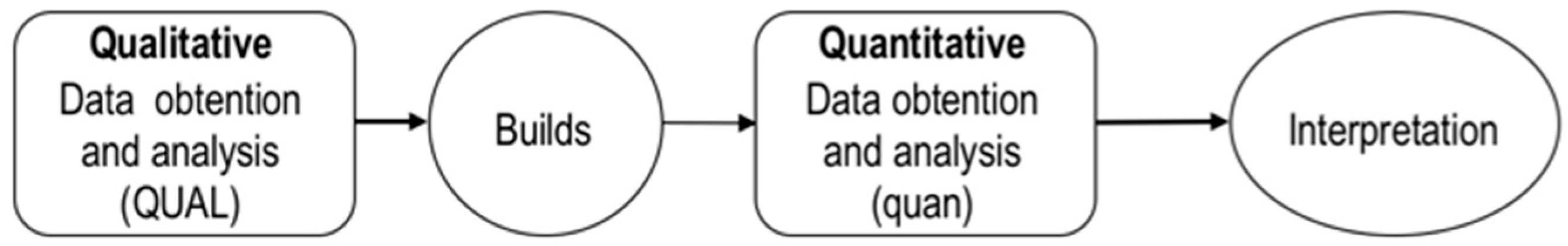

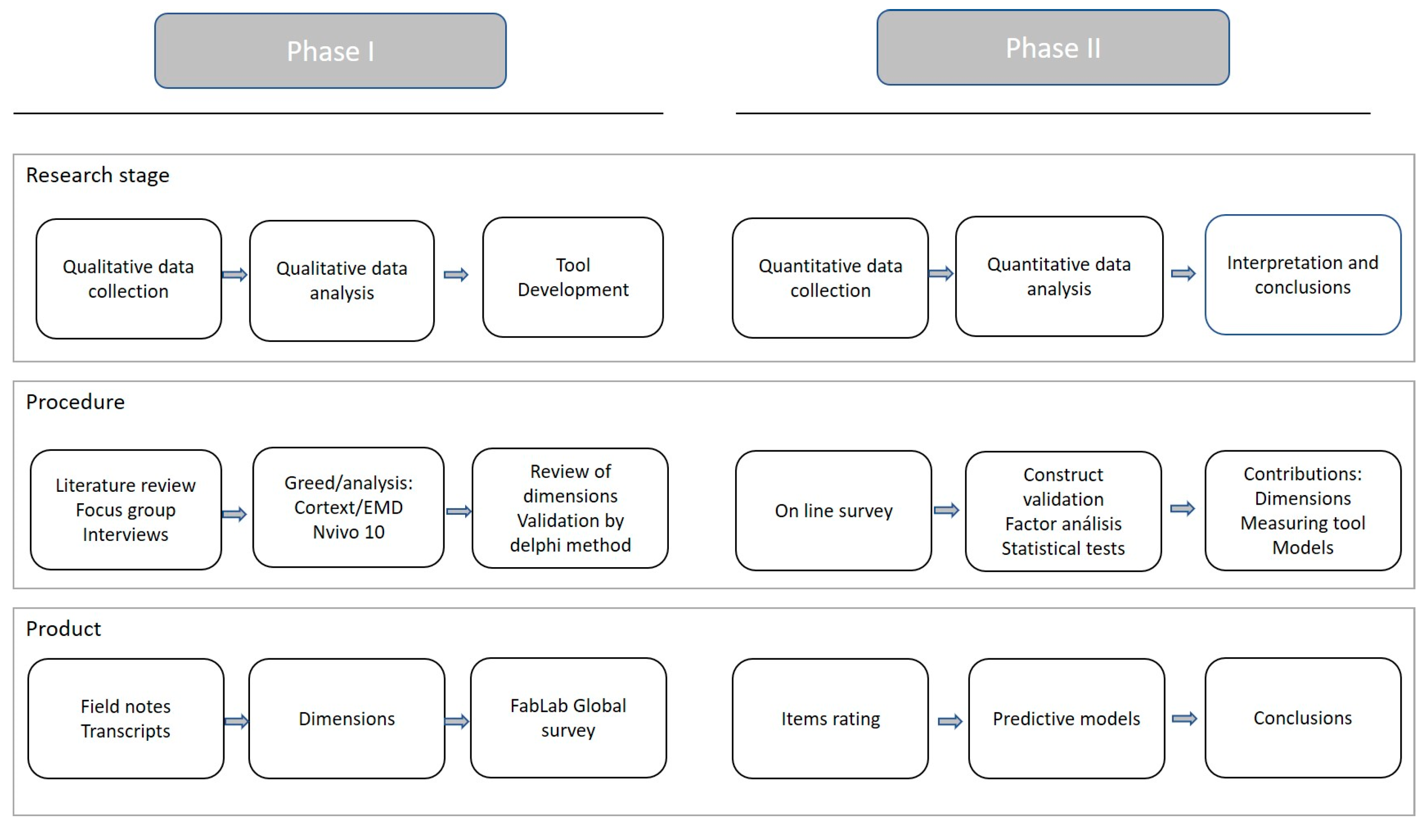

2. Materials and Methods

- -

- Documentation processes as elements of knowledge generation in FabLabs.

- -

- The innovative processes developed in FabLabs.

- -

- The independence and management of FabLabs.

- -

- FabLabs as generators of new economic initiatives.

- -

- The characterisation of the business model present in the FabLab.

Hypothesis Definition

3. Results

- Block I: Descriptive data to the main characteristics of FabLab.

- Block II: Description of the business model.

- Block III: Focused on innovation processes and documentation in the FabLab.

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Foray, D.; Lundvall, B. The knowledge-based economy: From the economics of knowledge to the learning economy. In The Economic Impact of Knowledge; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 1998; pp. 115–121. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. Innovation Management and the Knowledge-Driven Economy ECSC-EC-EAEC; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Naboni, R.; Paoletti, I. The third industrial revolution. In Advanced Customization in Architectural Design and Construction; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2015; pp. 7–27. [Google Scholar]

- Iivari, N.; Molin-Juustila, T.; Kinnula, M. The future digital innovators: Empowering the young generation with digital fabrication and making. In Proceedings of the 2016 International Conference on Information Systems, ICIS 2016, Dublin, Ireland, 11–14 December 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Jolly, A.-M.; Leger, C. French engineering universities: How they deal with entrepreneurship and innovation. In Proceedings of the Engineering Education for a Smart Society: World Engineering Education Forum and Global Engineering Deans Council, Seoul, Republic of Korea, 6 November 2016; Springer International Publishing: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2018; pp. 284–294. [Google Scholar]

- Krannich, D.; Robben, B.; Wilske, S. Digital fabrication for educational contexts. In Proceedings of the 11th International Conference on Interaction Design and Children, Bremen, Germany, 12–15 June 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Moilanen, J. Emerging hackerspaces—Peer-production generation. IFIP Adv. Inf. Commun. Technol. 2012, 378, 94–111. [Google Scholar]

- Greer, C.R.; Lei, D. Collaborative Innovation with Customers: A Review of the Literature and Suggestions for Future Research. Int. J. Manag. Rev. 2012, 14, 63–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryzhkova, N. Does online collaboration with customers drive innovation performance? J. Serv. Theory Pract. 2015, 25, 327–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velasco, E.; Zamanillo, I.; Gurutze, M. Evolución de los modelos sobre el proceso de innovación: Desde el modelo lineal hasta los sistemas de innovación. In Decisiones Basadas en el Conocimiento y en el Papel Social de la Empresa: XX Congreso Anual de AEDEM; ESIC Editorial: Barcelona, Spain, 2007; pp. 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Landry, R.; Amara, N.; Lamari, M. Does social capital determine innovation? To what extent. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2002, 69, 681–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dosi, G. Technological paradigms and technological trajectories. A suggested interpretation of the determinants and directions of technical change. Res. Policy 1982, 11, 147–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, W.; Levinthal, D. Absorptive capacity: A new perspective on learning and innovation. Adm. Sci. Q. 1990, 35, 128–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dogson, M. The Management of Technological Learning: Lessons from a Biotechnology Company; Walter & Gruyter: Berlin, Germany, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. Green Paper on Innovation; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Kline, S.J.; Rosenberg, N. An Overview of Innovation. Eur. J. Innov. Manag. 1986, 38, 275–305. [Google Scholar]

- Chesbrough, H.W. The era of Open Innovation. MIT Sloan Manag. Rev. 2003, 44, 35–42. [Google Scholar]

- Acs, Z. Regional Innovation, Knowledge and Global Change; Cengage Learning: New York, NY, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Edquist, C. Systems of Innovation: Technologies, Institutions and Organizations, Long Range Plann; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Landry, R.; Amara, N. The Chaudières-Appalache System of Industrial Innovation, Local Reg. Syst. Innov. 1988, 257–276. [Google Scholar]

- Porter, M.E. Clusters and the new economics of competition. Harv. Bus. Rev. 1998, 76, 77–90. [Google Scholar]

- Porter, M.E. Location, Competition, and Economic Development: Local Clusters in a Global Economy. Econ. Dev. Q. 2000, 14, 15–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teece, D.J. Knowledge and competence as strategic assets. In Handbook on Knowledge Management 1; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2004; Volume 40, pp. 129–152. [Google Scholar]

- Forrest, J.E. Models of the process of technological innovation. Technol. Anal. Strateg. Manag. 1991, 3, 439–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godin, B. The Linear Model of Innovation: The Historical Construction of an Analytical Framework. Sci. Technol. Human Values 2006, 31, 639–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirowsky, P.; Sent, E.M. Commercialization of Science and the Response of STS. In The Handbook of Science and Technology Studies; Hackett, E.J., Amsterdamska, O., Lynch, M.E., Wajcman, J., Bijker, W.E., Eds.; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2008; pp. 635–689. [Google Scholar]

- Rothwell, R. Towards the Fifth generation Innovation Process. Int. Mark. Rev. 1994, 11, 7–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulej, M.; Kajzer, S.; Potocan, V.; Rosi, B.; Knez-Riedl, J. Interdependence of systems theories—Potential innovation supporting innovation. Kybernetes 2006, 35, 942–954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mowery, D.; Rosenberg, N. The influence of market demand upon innovation: A critical review of some recent empirical studies. Res. Policy 1979, 8, 102–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Von Hippel, E. The Sources of Innovation; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1988; Volume 132. [Google Scholar]

- Nelson, R.R. National Innovation Systems: A Comparative Analysis; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Niosi, J.; Saviotti, P.; Bellon, B.; Crow, M. National systems of innovation: In search of a workable concept. Technol. Soc. 1993, 15, 207–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chesbrough, H. The logic of open innovation: Managing intellectual property. Calif. Manag. Rev. 2003, 45, 33–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enkel, E.; Gassmann, O.; Chesbrough, H. Open R&D and open innovation: Exploring the phenomenon. R D Manag. 2009, 39, 311–316. [Google Scholar]

- Gassmann, O.; Enkel, E.; Chesbrough, H. The future of open innovation. R D Manag. 2010, 40, 213–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, J.; Matias, J.C. Open innovation 4.0 as an enhancer of sustainable innovation ecosystems. Sustainability 2020, 12, 8112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walter-Herrmann, J.; Büching, C. FabLab: Of Machines, Makers and Inventors; Transcript Verlag: Bielefeld, Germany, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Fleischmann, K.; Hielscher, S.; Merritt, T. Making things in Fab Labs: A case study on sustainability and co-creation. Digit. Creat. 2016, 27, 113–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos Arias, F. From the Bauhaus to the Fab Lab. The digital revolution of learning by doing. EGA Expresión Gráfica Arquit. 2021, 26, 192–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pila, A.D. How a Fab Lab can drive ordinary people to become engineering enthusiasts and help to make a better society. In Advances in The Human Side of Service Engineering, Proceedings of the AHFE 2016 International Conference on The Human Side of Service Engineering, Walt Disney World®, Lake Buena Vista, FL, USA, 27–31 July 2016; Springer International Publishing: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2017; pp. 355–364. [Google Scholar]

- Mortara, L.; Parisot, N.G. How Do Fab-Spaces Enable Entrepreneurship? Case Studies of ‘Makers’ Who Became Entrepreneurs. Int. J. Manuf. Technol. Manag. 2018, 32, 16–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pengelly, J.; Fairburn, S.; Newlands, B. Adopting ’Fablab’ Model to Embed Creative Entrepreneurship Across Design Program. In Proceedings of the 14th International Conference on Engineering & Product Design Education (E&PDE12) Design Education for Future Wellbeing, Antwerp, Belgium, 6–7 September 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Hartikainen, H.; Ventä-Olkkonen, L.; Kinnula, M.; Iivari, N. Entrepreneurship Education Meets FabLab: Lessons Learned with Teenagers. In Proceedings of the FabLearn Europe/MakeEd 2021—An International Conference on Computing, Design and Making in Education (FabLearn Europe/MakeEd 2021), New York, NY, USA, 2–3 June 2021; pp. 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berni, A.; Dallago, F.; Maccioni, L.; Concli, F.; Borgianni, Y. The Role of Rapid Prototyping Devices in the Design and Manufacturing Practices of FabLab Visitors: A Survey. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Design, Simulation, Manufacturing: The Innovation Exchange, Lviv, Ukraine, 8–11 June 2021; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 401–409. [Google Scholar]

- Fab Academy Program. Available online: https://fabacademy.org/ (accessed on 12 March 2023).

- Maravilhas, S.; Martins, J.S.B. Information management in fab labs: Avoiding information and communication overload in digital manufacturing. In Information and Communication Overload in the Digital Age; UNIFACS Salvador University; IGI Global: Salvador, Brazil, 2017; pp. 246–270. [Google Scholar]

- Guerra Guerra, A.; De Gómez, L.S. From a FabLab towards a Social Entrepreneurship and Business Lab. J. Cases Inf. Technol. 2016, 18, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruberto, F. Fablabs as New Innovation Infrastructure for the Italian Industry. IOSR J. Bus. Manag. III 2015, 17, 2319–7668. [Google Scholar]

- Stacey, M. The FAB LAB Network: A Global Platform for Digital Invention, Education and Entrepreneurship. Innov. Technol. Gov. Glob. 2014, 9, 221–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lô, A. A corporate FabLab to promote employees’ ambidexterity: Renault Case Study. Rev. Fr. Gest. 2017, 264, 81–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fagbohoun, S. Fablab interne: Quels effets sur le contexte organisationnel? Le cas d’un cabinet de conseil. Innovations 2021, 66, 79–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lô, A. Fab Lab en entreprise: Proposition d’ancrage théorique. In Proceedings of the XXIII ème Conférence Annuelle de l’Association Internationale de Management Stratégique, Rennes, France, 26–28 May 2014; pp. 25–27. [Google Scholar]

- Le Journal des Activités Sociales de l’Energie. Available online: https://journal.ccas.fr/design-lab-l2r-le-fablab-dedf/ (accessed on 12 March 2023).

- Lena-Acebo, F.J.; García-Ruiz, M. E Spanish FabLabs Cartography. In Proceedings of the 14th Iberian Conference on Information Systems and Technologies (CISTI), IEEE, Coimbra, Portugal, 19–22 June 2019; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Ruiz, E. Between differentiation and integration: Fostering exploration innovation thanks to the internal Fab Lab, the case of the i-Lab (Air Liquide). Innovations 2021, 65, 219–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FabFoundation. The FabLab Charter. Available online: https://fabfoundation.fablabbcn.org/index.php/the-fab-charter/index.html (accessed on 12 March 2023).

- Savastano, M.; Bellini, F.; D’Ascenzo, F.; Scornavacca, E. FabLabs as platforms for digital fabrication services: A literature analysis. In Proceedings of the 8th International Conference on Exploring Service Science, IESS 2017, Rome, Italy, 24–26 May 2017; Management Department, Sapienza University: Rome, Italy, 2017; Volume 279, pp. 24–37. [Google Scholar]

- FABFOUNDATION2022. 2022. Available online: https://fabfoundation.org/ (accessed on 12 March 2023).

- Creswell, J.; Clark, V. Designing and Conducting Mixed-Methods Research; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Creswell, J.W. Research Design: Qualitative, Quantitative, and Mixed Methods Approaches; Sage Publications: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Lena Acebo, F.J.; García-Ruiz, M.E. FabLab Global Survey. Resultados de un Estudio Sobre el Desarrollo de la Cultura Colaborativa; LULU Press: Raleigh, NC, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.F.; Black, W.C.; Babin, B.J.; Anderson, R.E. Multivariate Data Analysis, 7th ed.; Pearson: London, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Soomro, S.A.; Casakin, H.; Georgiev, G.V. A Systematic Review on FabLab Environments and Creativity: Implications for Design. Buildings 2022, 12, 804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Ruiz, M.-E.; Lena-Acebo, F.-J. FabLabs: The Road to Distributed and Sustainable Technological Training through Digital Manufacturing. Sustainability 2022, 14, 3938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scarmoncin, A.; Portelli, C.; Osorio, F.; Eckerlein, G. Unfolding innovation lab services in public hospitals: A hospital FabLab case study. In Proceedings of the 28th International Conference on Engineering, Technology and Innovation (ICE/ITMC) and 31st International Association for Management of Technology (IAMOT), Nancy, France, 19–23 June 2022. [Google Scholar]

| Dosi, 1982 [12] | A particular process of the problem resolution property of the company. |

| Cohen and Levinthal, 1990 [13], Dogson, 1991 [14] | A varied and diverse learning process in which internal and external sources of knowledge are included as well as the absorption capacity of themselves from the companies. |

| European Commission, 1995 [15] | The renewal or update of the range of products and services offered by companies, the creation of new production models, and the implementation of changes in the work management or organization. |

| Kline and Rosenberg, 1986 [16] | A formal and informal interactive process that involves interactions between companies and commercial networks with different participants from the company’s environment. |

| Chesbrough, 2003 [17] | A temporarily cyclical process in which the previously obtained benefits are invested to enhance the development of its products, which, in turn, are protected by restrictive intellectual property policies that allow the company to create new features or its new products. |

| Acs, 2000 [18] Edquist, 1997 [19] Landry and Amara, 1988 [20] Porter, 1998 and 2000 [21,22] Teece, 2004 [23] | A process that occurs mainly in commercial companies where the contribution of government agencies and public research institutions is kept on a minor scale. |

| Main Assertions | From |

|---|---|

| “There are several types of FabLab, […] but it is clear that those within a university and primarily dedicated to the university’s students and their projects… are unlikely to innovate much.” | Focus Group (May 2015) |

| “Our FabLab is at the service of the university and its students, so innovation takes a back seat.” | FabManaager D.G. (October 2015) |

| “The FabLab is just another tool of the University, in fact, it occupies the space of what used to be the Reprographics department… among the printing plotters, and with the oversaturation of tasks, little innovation is taking place.” | FabManage F.S. (October 2015) |

| “Innovation? Our innovation is providing students with fantastic tools, contributing to their education, contributing to knowledge…” | FabManager J.C.P.J. (May 2015) |

| “The FabLab belongs to the University and serves its students […] in addition, we have been operating for a short time and no significant projects have been proposed yet.” | FabManager: S.K. (October 2015) |

| Hypothesis I.1. Innovation processes are influenced by the FabLab’s primary dedication to educational environments. | |

| H.I.1.1. Innovation processes are influenced by the FabLab’s dedication to educational processes. H.I.1.2. Innovation processes are influenced by the FabLab’s dedication to students. | |

| Main Assertions | From |

|---|---|

| “There are many cutting-edge FabLabs in innovation, but of course, they are dedicated to that, to innovation, to developing things….” | FabManager J.C.P.P.J (May 2015) |

| “Serious innovation, the real one, is developed in important FabLabs, which are dedicated to that, which bring products forward…” | Focus Group (May 2015) |

| Hypothesis I.2. The innovation processes are influenced by the FabLab’s dedication to students | |

| Main Assertions | From |

|---|---|

| “Of course, when the FabLab channels the full potential of a university and does not exclusively focus on the students, that innovation occurs.” | Focus Group (May 2015) |

| “We have several projects with important companies, innovative projects…” | FabManager T.D. (October 2015) |

| “When a large company participates alongside a FabLab, that’s when you see that they are seeking true innovation, serious innovation, a change that they may not find in the usual processes of that Company” | Focus Group (May 2015) |

| Factors of innovation developed in a FabLab: collaboration with other laboratories. | Focus Group (May 2015) |

| Hypothesis I.3. The innovation processes in FabLabs are influenced by joint participation in project development. | |

| H.I.3.1. The processes of innovation in FabLabs are influenced by joint participation in projects developed with other laboratories. H.I.3.2. The innovation processes are influenced by the joint participation in projects developed in universities. H.I.3.3. The processes of innovation are influenced by the participation in joint projects with large companies | |

| Hypothesis I.1. The innovation processes are influenced by FabLab’s priority dedication to educational environments. H.I.1.1. The innovation processes are influenced by the FabLab’s dedication to the educational methods. H.I.1.2. The innovation processes are influenced by the FabLab’s dedication to students. Hypothesis H.I.2. The innovation processes in the FabLabs are influenced by their dedication to research and development projects. Hypothesis H.I.3. The innovation processes in the FabLabs are influenced by the joint participation in the project’s implementation. H.I.3.1. The innovation processes are influenced by joint participation in projects developed with other laboratories. H.I.3.2. The innovation processes are influenced by the joint participation in projects developed in Universities. H.I.3.3. The innovation processes are influenced by joint participation in projects with large companies. |

| The main contribution of the FabLab is oriented towards education. Current FabLab users: mainly university students. |

| The FabLab’s main contribution is its focus on research and product development. Existence of projects developed with the FabLab Network. Existence of projects developed with university institutions. Existence of joint participation in programmes with large companies. High percentage of innovation projects developed (more than 50% of the projects). |

| H | Variable | Pearson χ2 | p | Phi | Evaluation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H.I.1.1 | Va | 6.247 | 0.012 * | −0.271 | Accepted |

| H.I.1.2 | Vb | 7.815 | 0.005 ** | −0.303 | Accepted |

| H.I.2 | Vc | 17.278 | 0.000 ** | 0.451 | Accepted |

| H.I.3.1 | Vd | 0.358 | 0.550 | - | Rejected |

| H.I.3.2 | Ve | 0.471 | 0.492 | - | Rejected |

| H.I.3.3 | Vf | 6.821 | 0.009 ** | 0.283 | Accepted |

| I.C. 95% for Exp (B) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | E.T. | Wald | df | Sig | Exp (B) | L | H | |

| Vf (H.I.3.3) | 1.519 | 0.671 | 5.116 | 1 | 0.024 | 4.566 | 1.225 | 17.022 |

| Vb (H.I.1.2) | −1.962 | 0.820 | 5.721 | 1 | 0.017 | 0.141 | 0.028 | 0.702 |

| Va (H.I.1.1) | −2.419 | 0943 | 6.581 | 1 | 0.010 | 0.089 | 0.014 | 0.565 |

| Vc (H.I.2) | 3.032 | 0.858 | 12.494 | 1 | 0.000 | 20.741 | 3.861 | 111.430 |

| Constant | 0.251 | 0.991 | 0.064 | 1 | 0.800 | 1.286 | ||

| χ2 Hosmer-Lemeshow = 4.531 (p = 0.476) | R2 Cox & Snell = 0.364 | |||||||

| Omnibus Test: χ2 = 38.499 (p = 0.000) | −2Log Probability = 62.678 | R2 Nagelkerke = 0.523 | ||||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

García-Ruiz, M.-E.; Lena-Acebo, F.-J.; Rocha Blanco, R. Early Stages of the Fablab Movement: A New Path for an Open Innovation Model. Sustainability 2023, 15, 8907. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15118907

García-Ruiz M-E, Lena-Acebo F-J, Rocha Blanco R. Early Stages of the Fablab Movement: A New Path for an Open Innovation Model. Sustainability. 2023; 15(11):8907. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15118907

Chicago/Turabian StyleGarcía-Ruiz, María-Elena, Francisco-Javier Lena-Acebo, and Rocío Rocha Blanco. 2023. "Early Stages of the Fablab Movement: A New Path for an Open Innovation Model" Sustainability 15, no. 11: 8907. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15118907

APA StyleGarcía-Ruiz, M.-E., Lena-Acebo, F.-J., & Rocha Blanco, R. (2023). Early Stages of the Fablab Movement: A New Path for an Open Innovation Model. Sustainability, 15(11), 8907. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15118907