Model of Key Factors in the Sustainable Growth of Small and Medium-Sized Enterprises Belonging to the First Nations

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Entrepreneurship, Innovation, and First Nations

2.2. Rapid-Growth Firms

| Author | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Concept | Cancino et al. [32] | Mueller and Thomas [33] | Kantis and Díaz [34] | Benavente [35] | Hidalgo et al. [36] | Awais and Manzoor [37] | Capelleras and Kantis [38] | Kantis et al. [39] | Barringer et al. [40] | Pšeničny et al. [30] | Segarra and Teruel [41] | Kantis et al. [29] | Kantis et al. [42] | Goedhuys and Sleuwaegen [43] |

| Share capital | * | * | * | * | ||||||||||

| Sci-tech platform | * | * | * | |||||||||||

| Educational system | * | * | * | * | * | |||||||||

| Conditions of the complaint | * | * | ||||||||||||

| Culture | * | * | * | * | ||||||||||

| Social conditions | * | * | * | |||||||||||

| Entrepreneurial human capital | * | * | ||||||||||||

| Business structure | * | * | * | * | ||||||||||

| Financing | * | * | * | * | * | |||||||||

| Government and public policy | * | * | * | * | * | |||||||||

| Team initiated company | * | * | * | * | ||||||||||

| Mission (focused on growth) | * | * | ||||||||||||

| Commitment to growth | * | * | * | * | * | |||||||||

| Emphasis on planning | * | * | ||||||||||||

| Low initial investment | * | * | * | * | ||||||||||

| Bootstrapping | * | * | * | * | * | |||||||||

| Innovation in products and/or services | * | * | ||||||||||||

| International relations | * | * | ||||||||||||

| Export orientation | * | |||||||||||||

| Investment in R&D | * | * | ||||||||||||

| Investment in innovation | * | * | * | |||||||||||

| Logistics and transport costs | * | |||||||||||||

| Located in metropolitan area | * | * | ||||||||||||

| Creating unique value | * | * | ||||||||||||

| Learning to learn | * | |||||||||||||

| Knowledge of the customer | * | |||||||||||||

| Motivation | * | * | * | * | ||||||||||

| Role models | * | * | ||||||||||||

| Start before age 35 | * | |||||||||||||

| Starting after age 35 | * | * | * | * | ||||||||||

| Contact networks | * | * | * | * | ||||||||||

| Linking with business mentors | * | |||||||||||||

| Internal control locus | * | |||||||||||||

| Experience as an employee | * | * | * | * | ||||||||||

| Undergraduate university education | * | * | * | * | * | * | ||||||||

| Postgraduate university education | * | * | * | |||||||||||

| Experience as an entrepreneur | * | * | * | * | * | * | ||||||||

| Relevant industry experience | * | * | * | * | ||||||||||

| Children of entrepreneurs | * | * | * | |||||||||||

| Male gender | * | * | * | |||||||||||

| Selectivity in recruitment | * | * | * | |||||||||||

| Empowerment of employees | * | * | ||||||||||||

| Training and coaching of employees | * | * | ||||||||||||

| Employee development | * | * | ||||||||||||

| Non-economic incentives to employees | * | * | * | |||||||||||

| Economic incentives to employees | * | * | * | |||||||||||

| Stock options to employees | * | * | ||||||||||||

2.3. Mapuche Context as a Relevant Case Study of the First Nations

3. Methodology

- Exploratory studies are carried out when the aim is to examine a subject that has not been studied before, or when there are many questions.

- The usefulness of exploratory research lies in the possibility of becoming familiar with unknown phenomena.

3.1. Partial Least Squares

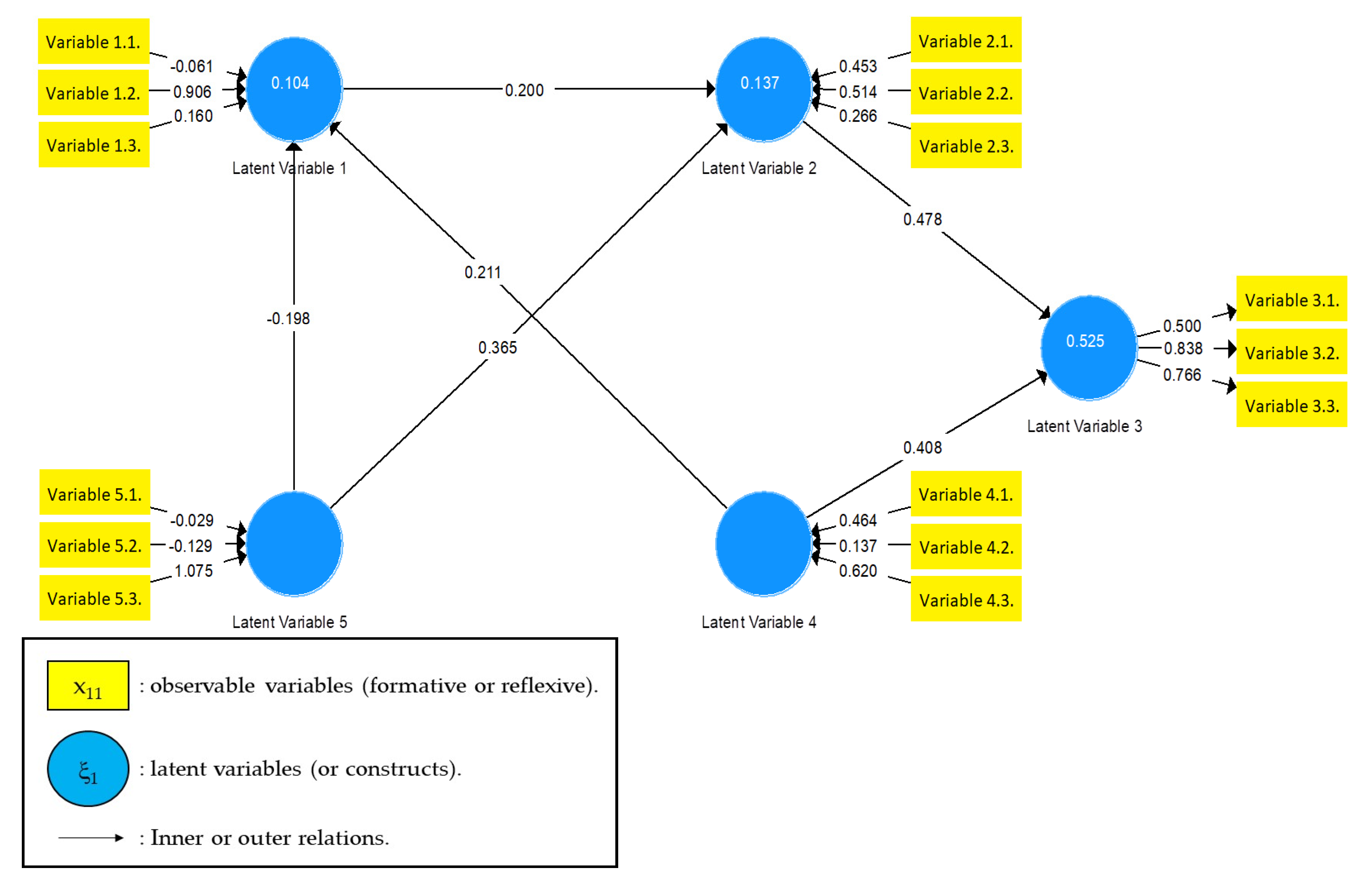

- The observable variables (or indicators) are in yellow rectangles.

- Latent variables (or constructs) are found in light blue circles.

- Observable variables are variables that can be measured.

- Latent variables that point to observable variables are called reflective variables. These are the model-dependent variables.

- Latent variables that are noted by their indicators are called formative variables. These are the model-independent variables.

- The values that accompany the arrows of the indicator variables toward their constructs are called weights.

- The values that accompany the arrows of the construct toward its indicator variables are called loads.

- The values that accompany the arrows between constructs are called path coefficients. They represent the relevance of the relationship between the variables.

- The set of observable variables and their relationships with their formative constructs is called the Formative Model.

- The set of observable variables and their relationships with their reflective constructs is called the Reflective Model.

- Arrows between latent variables are called paths (or latent variable relationships).

- Variables from which the route departs are called exogenous.

- Variables that receive routes are called endogenous.

- The value within each endogenous latent variable corresponds to the indicator and implies the amount of variance explained by the combination of exogenous latent variables that point to it.

- The set of latent variables (or constructs) and their paths is called the Structural Model.

3.2. Survey

- Closed questions, i.e., possible answers have been delimited and they must be limited to these possibilities.

- A Likert scale was developed for possible answers for statements related to the variables to be measured, with the following options: “Strongly agree”, “Agree”, “Doesn’t care”, “Disagrees”, “Strongly disagrees” (for which the criterion suggested by Hair et al. [48] was also considered). It was coded from 4 to 0, where “Strongly agree” equals 4 and “Strongly disagree” equals 0.

- In addition, questions were considered with only two options, True and False, taking advantage of the PLS possibility to work with different measuring scales.

- For survey validation, expert judgment was employed. To achieve this, the support of four experts was enlisted, selected for their experience in the study and development of public policies for innovation and entrepreneurship: (1) a Ph.D. with expertise in entrepreneurship and innovation, (2) a business incubator director, (3) a representative from the public sector in charge of innovation studies and programs, who works for the Government of Chile; (4) an entrepreneur with over 15 years of experience. The study objectives and methodology were explained to them, including a question-by-question review and their relationships with the variables under study. Based on their experience, they suggested improvements to the survey to enhance the comprehensibility of the phenomenon being measured.

- The strategy of asking one question for each variable observed was adopted.

- We worked so that the questions fulfilled the following characteristics:

- °

- Clear, precise, and understandable questions.

- °

- Brief questions.

- °

- Use of simple vocabulary

- °

- Avoidance of any questions that might seem uncomfortable.

- °

- Precise questions in terms of the aspect to be measured.

- °

- Avoidance of inducing responses.

4. Model Development

4.1. Selection of the Sample

4.1.1. Description of the Sample to Be Studied

4.1.2. The Sample

- Ten times the number of relationships of the latent variable or construct with the most connections.

- Ten times the number of causal relationships of the latent variable with more structural pathways.

- N: Population size, in this case, 83 entrepreneurs;

- : For a confidence level of 90%, 1.65;

- d: 10% error;

- p = q = 0.5.

4.2. Data Collection

4.3. Description of Interviewees

4.4. Definition of the Dependent Variable

- Growth rate by sales:

- 2.

- Growth rate in size:

- 3.

- Due to the diversity of economic activities, and the age of the companies, among others, there is a great disparity in the income from sales between the enterprises, which brings about a high variability. To mitigate the effect of the high variability of the data, it was decided to stratify the enterprises based on their annual income, generating four conglomerates with the following criteria:

- Number of cases completed: 37;

- Conglomeration method: k-Average;

- Distance metrics: Euclidian;

- Conglomeration: observations;

- Standardize: yes.

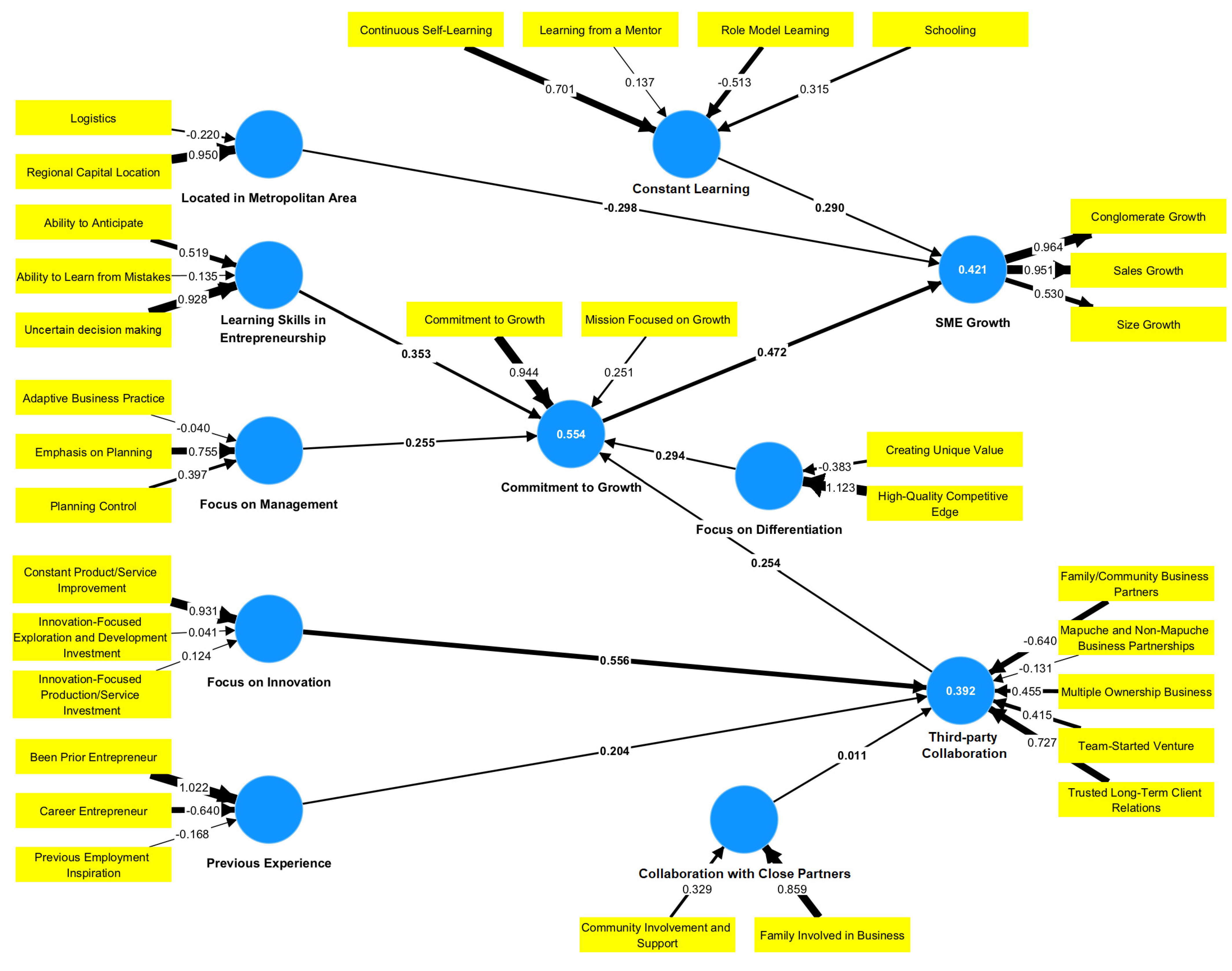

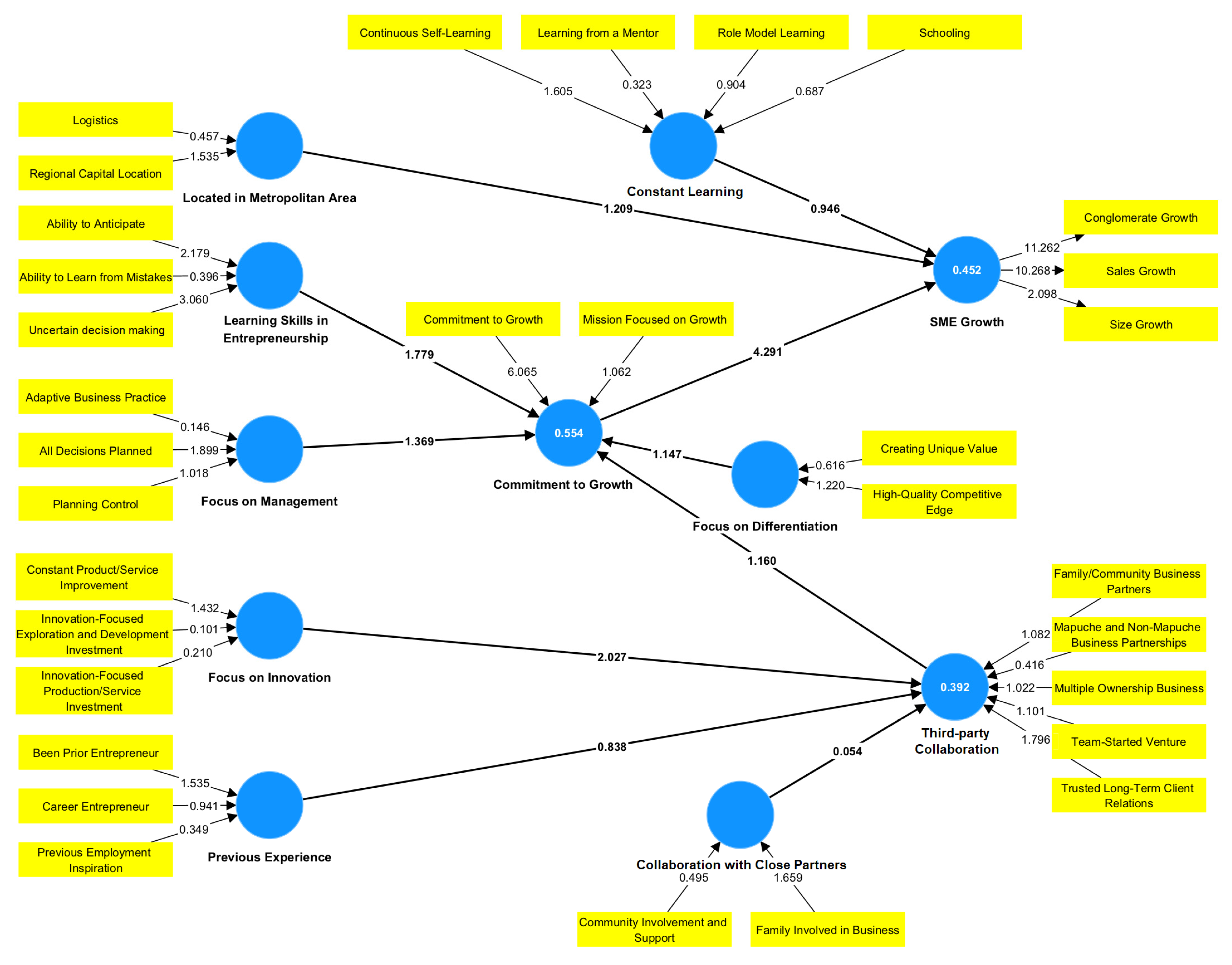

4.5. Proposed Model

4.5.1. Evaluation of the Reflective Measurement Model

- Cronbach’s Alpha measures the internal consistency and provides a reliability value based on the intercorrelations of the observed variables of the reflective construct. It has the disadvantage of assuming that all indicators are equally reliable; on the other hand, PLS favors reflective indicators according to their individual reliability, so the following indicator is used in combination.

- Composite Reliability Indicator

4.5.2. Evaluation of the Formative Measurement Model

- Logistics;

- Adaptative Business Practice;

- Innovation-Focused Production/Service Investment;

- Previous Employment Inspiration;

- Community Involvement and Support;

- Multiple-Ownership Business;

- Mapuche and Non-Mapuche Business Partnerships;

- Schooling;

- Learning from a Mentor.

4.5.3. Evaluation of the Structural Model

- In addition to the coefficient of determination, , it is possible to evaluate the size of the effect, , which represents the effect of the change in the values of (Equation (7)) if any of the exogenous variables of the model are not found, and the values of 0.02, 0.15, and 0.35 reflect small, medium, or large effects, respectively, of an exogenous construct. A good quality of the values was obtained, except for the relationship between Focus on Management to Commitment to Growth and from Third-party Collaboration to Commitment to Growth, whose values are below what is considered an average effect, although further away from what is considered a small effect, as shown in Table 11.

5. Discussion of Results

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

Appendix A.1. Preliminary Questions

Appendix A.2. Questions Used to Build the Models

- In the country, there are needed conditions to develop businesses based on science and technology.

- The Chilean educational system helps in the training of future entrepreneurs.

- There is a large number of talented entrepreneurs belonging to the First Nations (e.g., Mapuche).

- The initial investment of your business was equal to or less than US$100,000.

- You use alternative sources of financing (postponed payments, purchase of used machinery, advance payments from customers, or credits from suppliers or others).

- All the decisions in your business are made under the framework of detailed planning.

- A permanent control of the accomplishment of planning is a fundamental task.

- You have no impediments to access to talk with large and medium-sized businessmen.

- Society and your community highly value your role as an entrepreneur.

- You have the same access to opportunities, contacts, and financing as entrepreneurs from other social classes or ethnic groups.

- When unsuccessful attempts or failures occur, you immediately look for who was at fault.

- You can anticipate difficulties and make decisions to avoid them.

- The Mapuche people must create successful businesses; if they have their own resources, they will be able to control their future as a nation.

- The Mapuche people must undertake, not only to improve their economic conditions, but also those of their people.

- You have become a businessman to have resources to preserve and strengthen your language, customs, and values.

- You strive for each product or service you offer to have a value that no one else can provide.

- In your company, it is very important that your products or services have a much higher quality than those offered by your competitors.

- Building ties with institutions or companies abroad is a common practice.

- Your business is exporting or working to do so in the short term.

- Your business is oriented to operate in global markets.

- You act when the problem or opportunity has appeared; you do not seek to anticipate the facts.

- When you made mistakes, you recognize them and have learned as much as possible from them.

- You have made complex decisions, despite not having had all the necessary information to do so.

- There is a good financing portfolio for your company.

- You feel real support from the Government, through its public policies in terms of financing and support for new business development.

- For the development of your business, you permanently rely on the contact networks that you have built throughout your life (relevant information, other contacts, financing sources, etc.).

- You create support networks, not only among Mapuche people but also with non-Mapuche entrepreneurs.

- Keeping in touch with former classmates has been useful to you in business.

- When analyzing a business opportunity, you do not consider reaching economic objectives only, but also objectives that go beyond them.

- Your family is involved in your business.

- Your community supports you and gets involved in your business.

- For you, as a businessman, environmental protection is a constant.

- In your business, you seek to minimize any negative impact on the environment.

- You feel great affection for your company, whose affection goes further than just receiving income.

- You feel a great commitment to the objectives of your business.

- Your main motivation for launching your business was to be able to fulfill yourself as a person.

- You raised your business to be your own boss.

- You started your business because you were unemployed.

- Part of your company’s income is used for research and development of new products (or services).

- You invest part of your income to create new solutions in services (or products) or to how you create or offer the service or product.

- You constantly strive to improve your products (or services) or create new ones.

- Your employees are very important, so you have an incentive policy (not necessarily monetary).

- You have developed a specific policy of economic incentives for your employees.

- Your employees have the possibility of accessing company shares.

- You have built a network of Mapuche companies that collaborate mutually.

- When looking for suppliers, you mainly buy from Mapuche suppliers and thus support each other.

- Before your current venture, you had other business attempts.

- Previously, you worked as an employee in the same area of your current business; there you were able to learn what you are developing today.

- You have never worked as an employee; you began your working life by undertaking.

- As a business practice, you do not rely on rules but adapt to circumstances and context.

- You are very selective with the people who make up your business since it is key to having reliable collaborators.

- You facilitate the empowerment of employees so that they feel more confident to make decisions.

- The training of your employees is a permanent practice.

- You establish lasting and trusting relationships with your customers, so you can learn about their preferences, needs, etc.

- Logistics and its costs are critical factors in your business; optimizing them is essential.

- You are constantly learning as an entrepreneur, whether self-taught or formal, learning is a lifelong practice.

- You follow successful businessmen as role models; you have read their biography, and try to follow in their footsteps (Steve Jobs, Henry Ford, Elon Musk, Jeff Bezos, etc.).

- You keep in touch with more experienced businessmen than you; they are your mentors.

- For you, the approval of your role as a businessman is important, both by your community and by other Mapuche people.

- Your current venture has been started by a team.

- Your business is owned by multiple partners.

- You have members of your family and/or community as partners.

- You have committed as a team to keep your business constantly growing.

- The mission of your company focuses on growth.

- Your company is located in a regional capital.

- You have promoted associations with Mapuche and non-Mapuche businessmen.

- You live and do business in your ancestral lands.

- You maintain a balance between your personal development, and your relationship with your community and with the different ecosystems present in your territory.

- For you, as a Mapuche, it is important to look for business opportunities that distribute the benefits, as a contribution to your community.

- As a businessman, when making decisions, you respect the role and leadership of your ancestral authorities.

References

- United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) Desiguales. Orígenes, Cambios y Desafíos de La Brecha Social En Chile; United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) Desiguales: Santiago, Chile, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Padilla Navarro, P.; Garín Contreras, A.; García Ojeda, M.; Bello Maldonado, Á. Mediciones del desarrollo y cultura: El caso del Índice de Desarrollo Humano y la población mapuche en Chile: Avances en torno a conceptos, metodología y evidencia empírica incorporando la noción de Küme Mogñen. Polis. Rev. Latinoam. 2015, 14, 165–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babyar, J. In search of Pan-American indigenous health and harmony. Glob. Health 2019, 15, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Department for International Development. Growth: Building Jobs and Prosperity in Developing Countries; Department for International Development: London, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Lindsay, N.J. Toward A Cultural Model of Indigenous Entrepreneurial Attitude. Acad. Mark. Sci. Rev. 2005, 5, 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Hidalgo Nuchera, A.; Pavón Morote, J.; León Serrano, G. La Gestión de la Innovación y la Tecnología en Las Organizaciones; Ediciones Pirámide: Madrid, Spain, 2014; ISBN 84-368-1702-8. [Google Scholar]

- Malik, K. Informe Sobre Desarrollo Humano 2013. El Ascenso del Sur: Progreso Humano en un Mundo Diverso; United Nations Development Programme: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Pizzi, A.; Brunet, I. Creación de empresas, modelos de innovación y pymes. Cuad. CENDES 2013, 30, 53–74. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Development Programme (UNDP). Uncertain Times, Unsettled Lives: Shaping Our Future in a Transforming World; Human Development Report 2021/2022; United Nations Development Programme (UNDP): New York, NY, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Britannica. Mapuche People. Available online: https://www.britannica.com/topic/Mapuche (accessed on 1 March 2023).

- Hernández Sampieri, R.; Fernández Collado, C.; Baptista Lucio, M.d.P. Metodología de la Investigación, 6th ed.; McGraw-Hill Education: Mexico City, Mexico, 2014; ISBN 978-1-4562-2396-0. [Google Scholar]

- Tidd, J.; Bessant, J. Managing Innovation: Integrating Technological, Market and Organizational Change, 7th ed.; Wiley: Exeter, UK, 2021; ISBN 9781119719335. [Google Scholar]

- Painecura Antinao, J. Charu: Sociedad y Cosmovisión en la Platería Mapuche; Ediciones Universidad Católica de Temuco: Temuco, Chile, 2011; ISBN 978-956-7019-77-9. [Google Scholar]

- Guevara, T. Los Araucanos En La Revolución de La Independencia; Universidad de Chile: Santiago, Chile, 1910. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, R.B. Corporate/indigenous partnerships in economic development: The first nations in Canada. World Dev. 1997, 25, 1483–1503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swinney, J.; Runyan, R. Native American Entrepreneurs and Strategic Choice. J. Dev. Entrep. 2007, 12, 257–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curry, J.A.; Donker, H.; Michel, P. Social entrepreneurship and indigenous people. J. Co-Oper. Organ. Manag. 2016, 4, 108–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macpherson, W.G.; Tretiakov, A.; Mika, J.P.; Felzensztein, C. Indigenous entrepreneurship: Insights from Chile and New Zealand. J. Bus. Res. 2021, 127, 77–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tretiakov, A.; Felzensztein, C.; Zwerg, A.M.; Mika, J.P.; Macpherson, W.G. Family, community, and globalization: Wayuu indigenous entrepreneurs as n-Culturals. Cross Cult. Strateg. Manag. 2020, 27, 189–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mika, J.P.; Felzensztein, C.; Tretiakov, A.; Macpherson, W.G. Indigenous entrepreneurial ecosystems: A comparison of Mapuche entrepreneurship in Chile and Māori entrepreneurship in Aotearoa New Zealand. J. Manag. Organ. 2022, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daher, M.; Jaramillo, A.; Rosati, A. Opportunities and tensions in supporting intercultural productive activities: The case of urban and rural Mapuche entrepreneurship programs. Cult. Psychol. 2021, 27, 286–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soto Hernández, D.; González Gálvez, M.; di Giminiani, P. Innovation as translation in Indigenous entrepreneurship: Lessons from Mapuche entrepreneurs in Chile. Can. J. Dev. Stud. Rev. Can. D’études Dév. 2022, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaafar, M.; Abdul Aziz, A.R.; Ali, R. Entrepreneurial characteristics of indigenous housing developers: The case of Malaysia. Econ. Ser. Manag. 2009, 12, 73–91. [Google Scholar]

- Berkes, F.; Adhikari, T. Development and conservation: Indigenous businesses and the UNDP Equator Initiative. Int. J. Entrep. Small Bus. 2006, 3, 671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, K.L.; Berkes, F.; Turner, N.J. Indigenous perspectives on ecotourism development: A British Columbia case study. J. Enterp. Communities People Places Glob. Econ. 2012, 6, 213–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, B.; Ou, W. Mainstream and new-stream patterns for indigenous innovation in China. J. Sci. Technol. Policy China 2013, 4, 55–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dana, L.-P.; Anderson, R.B. International Handbook of Research on Indigenous Entrepreneurship; Edward Elgar Publishing Limited: Cheltenham, UK, 2007; ISBN 978-1-84376-834-0. [Google Scholar]

- Foley, D.; O’Connor, A.J. Social Capital and the Networking Practices of Indigenous Entrepreneurs. J. Small Bus. Manag. 2013, 51, 276–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kantis, H.; Gonzalo, M.; Álvarez, P. ¿Emprendedores “ambiciosos” en Argentina, Chile y Brasil?: El Papel del Aprendizaje y del Ecosistema en la Creación de Nuevas Empresas Dinámicas. Pymes Innov. Desarro. 2014, 2, 33–60. [Google Scholar]

- Pšeničny, V.; Jakopin, E.; Vukčević, Z.; Ćorić, G. Dynamic entrepreneurship—Generator of sustainable economic growth and competitiveness. Manag. J. Contemp. Manag. Issues 2014, 19, 61–92. [Google Scholar]

- Fischer, E.; Reuber, A.R. Support for Rapid-Growth Firms: A Comparison of the Views of Founders, Government Policymakers, and Private Sector Resource Providers. J. Small Bus. Manag. 2003, 41, 346–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cancino, C.; Coronado, F.; Farias, A. Antecedentes y Resultados de Emprendimientos Dinámicos en Chile: Cinco Casos de Éxito. Innovar 2012, 22, 19–32. [Google Scholar]

- Mueller, S.L.; Thomas, A.S. Culture and entrepreneurial potential. J. Bus. Ventur. 2001, 16, 51–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kantis, H.; Díaz, S. Estudio de Buenas Prácticas. Innovación y Emprendimiento en Chile: Una Radiografía de Los Emprendedores Dinámicos y de sus Prácticas Empresariales; Endeavor Chile: Santiago, Chile, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Benavente, J.M. El Proceso Emprendedor en Chile; Inter-American Development Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Hidalgo, G.; Kamiya, M.; Reyes, M. Emprendimientos Dinámicos en América Latina. Avances en Prácticas y Políticas; Development Bank of Latin America: Caracas, Venezuela, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Awais Ahmad Tipu, S.; Manzoor Arain, F. Managing success factors in entrepreneurial ventures: A behavioral approach. Int. J. Entrep. Behav. Res. 2011, 17, 534–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capelleras Segura, J.L.; Kantis, H. Nuevas Empresas en América Latina: Factores que Favorecen su Rápido Crecimiento, 1st ed.; Universidad Autónoma de Barcelona: Barcelona, Spain, 2009; ISBN 978-84-612-9676-7. [Google Scholar]

- Kantis, H.; Angelelli, P.; Moori Koenig, V. Developing Entrepreneurship. Experience in Latin America and Worldwide; Inter-American Development Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2005; ISBN 193100398X. [Google Scholar]

- Barringer, B.R.; Jones, F.F.; Neubaum, D.O. A quantitative content analysis of the characteristics of rapid-growth firms and their founders. J. Bus. Ventur. 2005, 20, 663–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Segarra, A.; Teruel, M. High-growth firms and innovation: An empirical analysis for Spanish firms. Small Bus. Econ. 2014, 43, 805–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Kantis, H.; Federico, J.; Ibarra García, S. Index of Systemic Conditions for Dynamic Entrepreneurship. A Tool for action in Latin America; Asociación Civil Red Pymes Mercosur Rafaela: Buenos Aires, Argentina, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Goedhuys, M.; Sleuwaegen, L. High-growth entrepreneurial firms in Africa: A quantile regression approach. Small Bus. Econ. 2010, 34, 31–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Di Giminiani, P. Entrepreneurs in the making: Indigenous entrepreneurship and the governance of hope in Chile. Lat. Am. Caribb. Ethn. Stud. 2018, 13, 259–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarstedt, M.; Cheah, J.-H. Partial least squares structural equation modeling using SmartPLS: A software review. J. Mark. Anal. 2019, 7, 196–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barclay, D.; Thompson, R.; Higgins, C.A. The partial least squares approach to causal modeling: Personal computer adoption and uses as an illustration. Technol. Stud. Spec. Issue Res. Methodol. 1995, 2, 284–324. [Google Scholar]

- Caballero Domínguez, A.J. SEM vs PLS: Un enfoque basado en la práctica. In Proceedings of the IV Congreso de Metodología de Encuestas, Pamplona, Spain, 20–23 September 2006; pp. 57–66. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.; Hult, T.; Ringle, C.; Sarstedt, M. A Primer on Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM), 2nd ed.; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2016; ISBN 9781483377452. [Google Scholar]

- Ruiz, M.A.; Pardo, A.; San Martín, R. Structural Equation Models. Pap. Psicól. 2010, 31, 34–45. [Google Scholar]

- Peng, Y.; Li, S.; Pei, X.; Hao, K. The Multivariate Regression Statistics Strategy to Investigate Content-Effect Correlation of Multiple Components in Traditional Chinese Medicine Based on a Partial Least Squares Method. Molecules 2018, 23, 545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Wang, H.; Ju, A.; Wang, L. Ultraviolet Spectroscopic Detection of Nitrate and Nitrite in Seawater Simultaneously Based on Partial Least Squares. Molecules 2021, 26, 3685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramírez-Correa, P.; Ramírez-Rivas, C.; Alfaro-Pérez, J.; Melo-Mariano, A. Telemedicine Acceptance during the COVID-19 Pandemic: An Empirical Example of Robust Consistent Partial Least Squares Path Modeling. Symmetry 2020, 12, 1593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arredondo-Méndez, V.H.; Para-González, L.; Mascaraque-Ramírez, C.; Domínguez, M. The 4.0 Industry Technologies and Their Impact in the Continuous Improvement and the Organizational Results: An Empirical Approach. Sustainability 2021, 13, 9965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vicente-Gonzalez, L.; Vicente-Villardon, J.L. Partial Least Squares Regression for Binary Responses and Its Associated Biplot Representation. Mathematics 2022, 10, 2580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oppenheim, A. Questionnaire Design, Interviewing and Attitude Measurement, 2nd ed.; Continuum: New York, NY, USA, 2000; ISBN 978-0826451767. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.F.; Sarstedt, M.; Ringle, C.M.; Mena, J.A. An assessment of the use of partial least squares structural equation modeling in marketing research. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2012, 40, 414–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chinowsky, P.S. Strategic Management in Engineering Organizations. J. Manag. Eng. 2001, 17, 60–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forcael, E.; Morales, H.; Agdas, D.; Rodríguez, C.; León, C. Risk Identification in the Chilean Tunneling Industry. Eng. Manag. J. 2018, 30, 203–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Lévy Mangin, J.-P.; Varela Mallou, J. Modelización con Estructuras de Covarianzas en Ciencias Sociales; NetBiblo S.L.: La Coruña, Spain, 2006; ISBN 978-8497451369. [Google Scholar]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Structural Equation Models with Unobservable Variables and Measurement Error: Algebra and Statistics. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 382–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miles, J. Tolerance and Variance Inflation Factor. In Wiley StatsRef: Statistics Reference Online; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2014; pp. 1–2. [Google Scholar]

- Kock, N. Common Method Bias in PLS-SEM. Int. J. e-Collab. 2015, 11, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Ruhanen, L.; Whitford, M. Racism as an inhibitor to the organisational legitimacy of Indigenous tourism businesses in Australia. Curr. Issues Tour. 2016, 21, 1728–1742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Author | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Concept | Jaafar et al. [23] | Berkes and Adhikari [24] | Lindsay [5] | Turner et al. [25] | Zhu and Ou [26] | Anderson [15] | Swinney and Runyan [16] | Dana and Anderson [27] | Foley and O’Connor [28] |

| Collective ownership | * | ||||||||

| Alliances between national and non-native entrepreneurs | * | ||||||||

| Focused on global markets | * | ||||||||

| Motivated by economic self-sufficiency for purposes of self-government | * | * | |||||||

| Motivated to improve the socio-economic conditions of their people | * | * | |||||||

| Motivation for the preservation and strengthening of ethnic factors | * | * | |||||||

| Economic and non-economic objectives | * | * | * | ||||||

| Involves the family and/or community | * | ||||||||

| Commitment to the objectives | * | ||||||||

| Emotional attachment of the owner to the business | * | ||||||||

| Family and community support | * | * | |||||||

| Adapting rather than relying on rules | * | ||||||||

| Use of networks with a dominant culture | * | ||||||||

| Education as a means of access to social capital | * | ||||||||

| Approval of networks by the community | * | ||||||||

| Proactivity | * | ||||||||

| Ability to learn from mistakes | * | ||||||||

| Tolerance to ambiguity | * | ||||||||

| Protection of the environment | * | ||||||||

| In their endeavor, they make use of his ancestral lands | * | ||||||||

| Balance between personal and community integrity and ecosystems | * | ||||||||

| Minimize negative impacts on the environment | * | ||||||||

| Seek opportunities that distribute benefits in the community | * | ||||||||

| Respect the role of traditional authorities in decision-making | * | ||||||||

| Variable | Categories | Percent (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 64.86% |

| Female | 35.14% | |

| Demographical distribution | Urban | 64.86% |

| Rural | 35.14% | |

| Territorial distribution | La Araucanía | 40.54% |

| Biobío | 13.51% | |

| Los Ríos | 13.51% | |

| Santiago | 27.3% | |

| Others | 5.4% | |

| Schooling | Postgraduate education | 16.22% |

| University education | 43.24% | |

| Technical studies | 13.51% | |

| Other studies | 2.7% | |

| Secondary education | 21.62% | |

| Primary education | 2.7% |

| Conglomerate | Members | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 5 | 13.51 |

| 2 | 8 | 21.62 |

| 3 | 11 | 29.73 |

| 4 | 13 | 35.14 |

| Growth Rate by Sales | Growth Rate in Size | |

|---|---|---|

| Average | 0.308727 | 0.238068 |

| Standard division | 0.431265 | 0.675961 |

| Coefficient of variation | 139.691% | 283.936% |

| Minimum | −0.119527 | 0 |

| Maximum | 1.47574 | 4 |

| Range | 1.59526 | 4 |

| Standard bias | 3.55783 | 12.7219 |

| Standard kurtosis | 1.25125 | 35.1776 |

| Cronbach’s Alpha | Composite Reliability | Average Variance Extracted | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Current value | 0.776 | 0.930 | 0.705 |

| Minimum expected | 0.7 | 0.7 | 0.7 |

| Latent Variable | Commitment to Growth | SME Growth | Third-Party Collaboration |

|---|---|---|---|

| Collaboration with Close Partners | 1.127 | ||

| Commitment to Growth | 1.032 | ||

| Constant Learning | 1.061 | ||

| Focus on Differentiation | 1.020 | ||

| Focus on Innovation | 1.095 | ||

| Focus on Management | 1.483 | ||

| Learning Skills in Entrepreneurship | 1.480 | ||

| Located in Metropolitan Area | 1.072 | ||

| Previous Experience | 1.067 | ||

| Third-party Collaboration | 1.134 |

| Cronbach’s Alpha | Composite Reliability | Average Variance Extracted | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Current value | 0.776 | 0.942 | 0.7 |

| Minimum expected | 0.7 | 0.7 | 0.7 |

| Latent Variable | Commitment to Growth | SME Growth | Third-Party Collaboration |

|---|---|---|---|

| Commitment to Growth | 1.009 | ||

| Constant Learning | 1.021 | ||

| Focus on Innovation | 1.000 | ||

| Focus on Management | 1.491 | ||

| Learning Skills in Entrepreneurship | 1.556 | ||

| Located in Metropolitan Area | 1.030 | ||

| Third-party Collaboration | 1.312 |

| Latent Variable | ||

|---|---|---|

| Commitment to Growth | 0.466 | 0.417 |

| SME Growth | 0.468 | 0.420 |

| Third-party Collaboration | 0.377 | 0.359 |

| Latent Variable | Commitment to Growth | SME Growth | Third-Party Collaboration |

|---|---|---|---|

| Commitment to Growth | 0.524 | ||

| Constant Learning | 0.181 | ||

| Focus on Innovation | 0.605 | ||

| Focus on Management | 0.062 | ||

| Learning Skills in Entrepreneurship | 0.157 | ||

| Located in Metropolitan Area | 0.168 | ||

| Third-party Collaboration | 0.097 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Melillanca, E.; Ramírez, M.; Forcael, E. Model of Key Factors in the Sustainable Growth of Small and Medium-Sized Enterprises Belonging to the First Nations. Sustainability 2023, 15, 8822. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15118822

Melillanca E, Ramírez M, Forcael E. Model of Key Factors in the Sustainable Growth of Small and Medium-Sized Enterprises Belonging to the First Nations. Sustainability. 2023; 15(11):8822. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15118822

Chicago/Turabian StyleMelillanca, Eric, Milton Ramírez, and Eric Forcael. 2023. "Model of Key Factors in the Sustainable Growth of Small and Medium-Sized Enterprises Belonging to the First Nations" Sustainability 15, no. 11: 8822. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15118822

APA StyleMelillanca, E., Ramírez, M., & Forcael, E. (2023). Model of Key Factors in the Sustainable Growth of Small and Medium-Sized Enterprises Belonging to the First Nations. Sustainability, 15(11), 8822. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15118822