Do New Luxury Hotel Promotions Harm Member Customers?

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Sales Promotions

2.2. Customer Regret

2.3. Customer Switching Intention

2.4. Research Hypotheses

3. Methodology

3.1. Study Design

3.2. Participants

3.3. Measures

4. Results

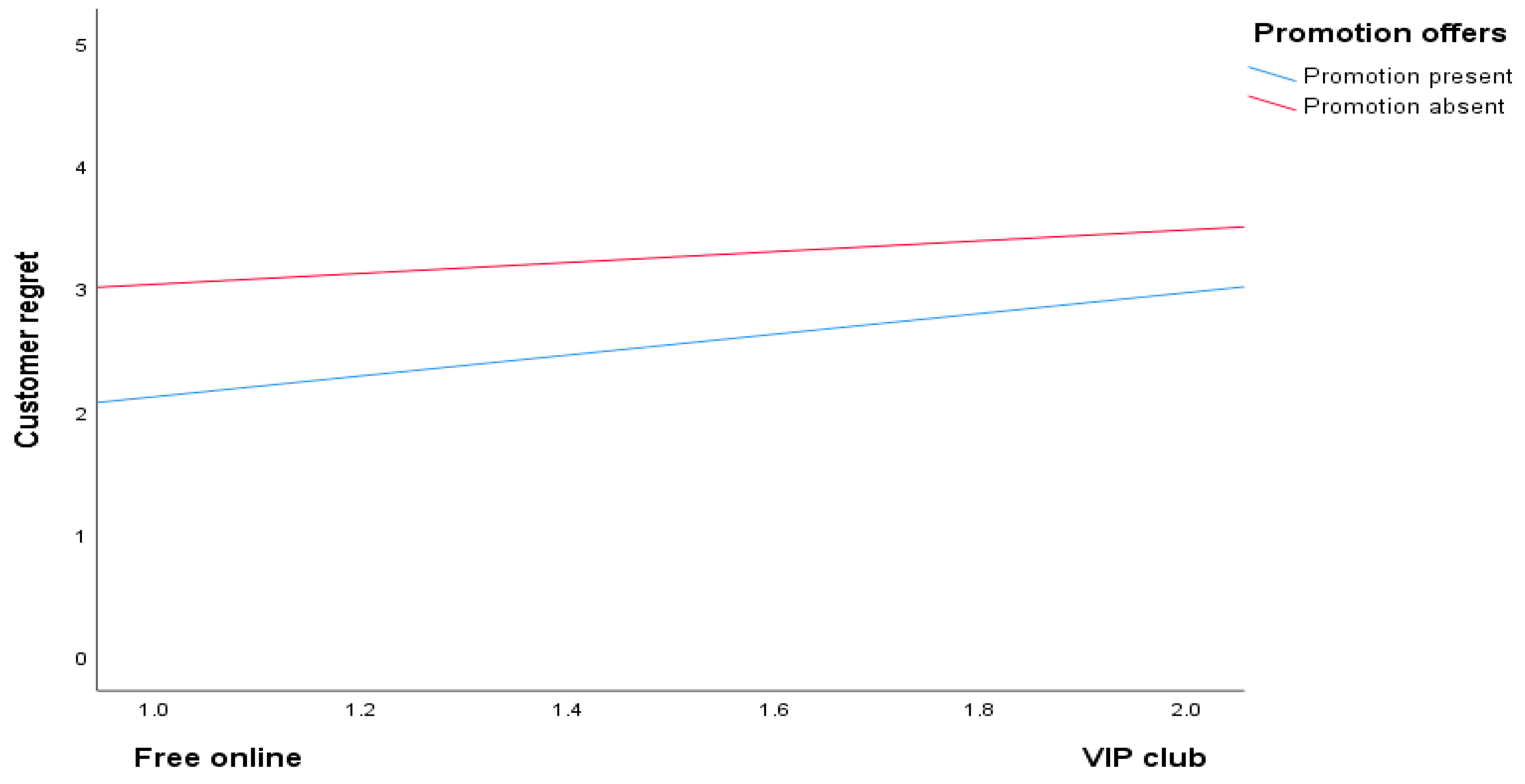

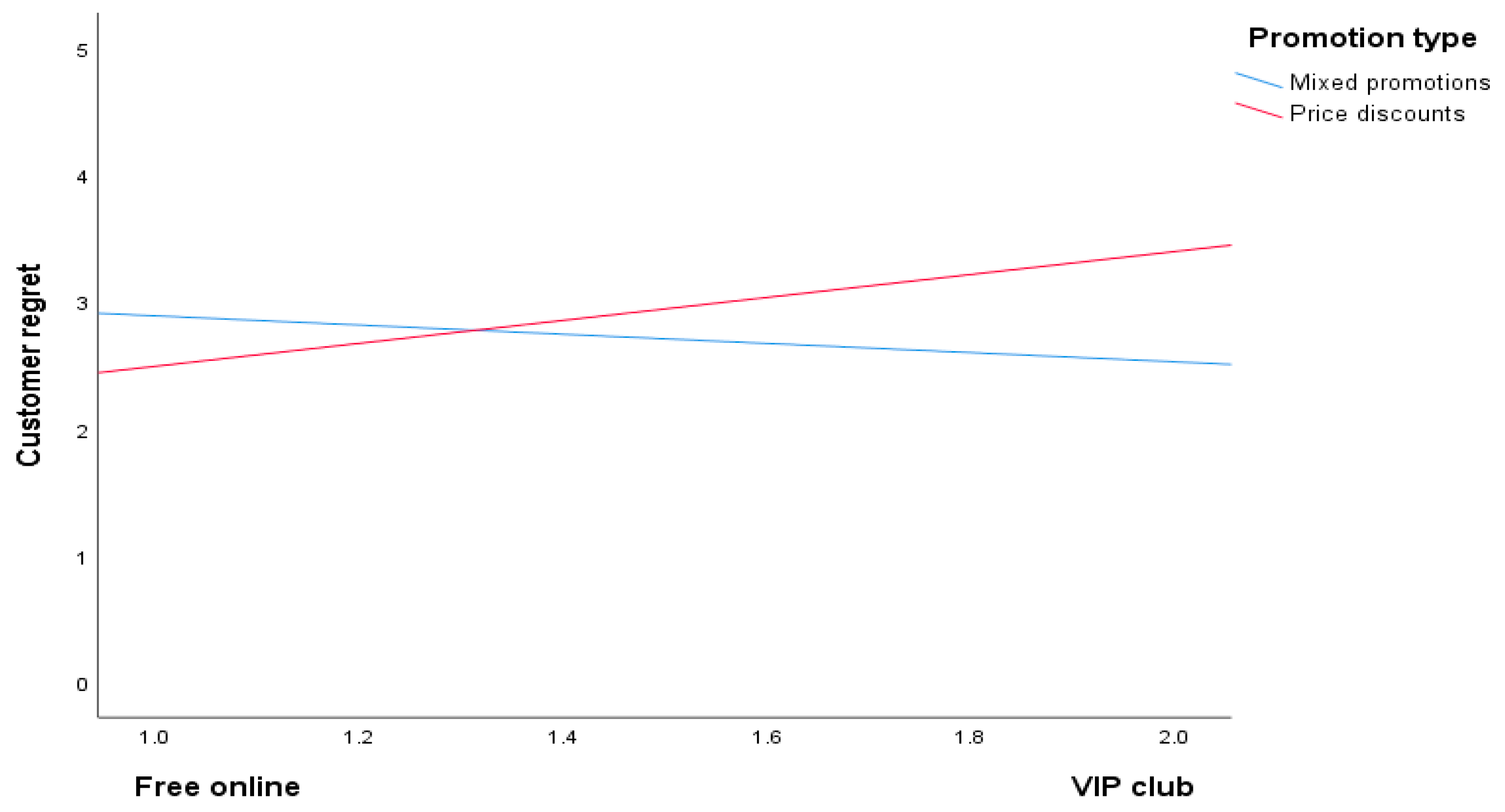

4.1. Customers’ Regret Regarding the New Luxury Hotel

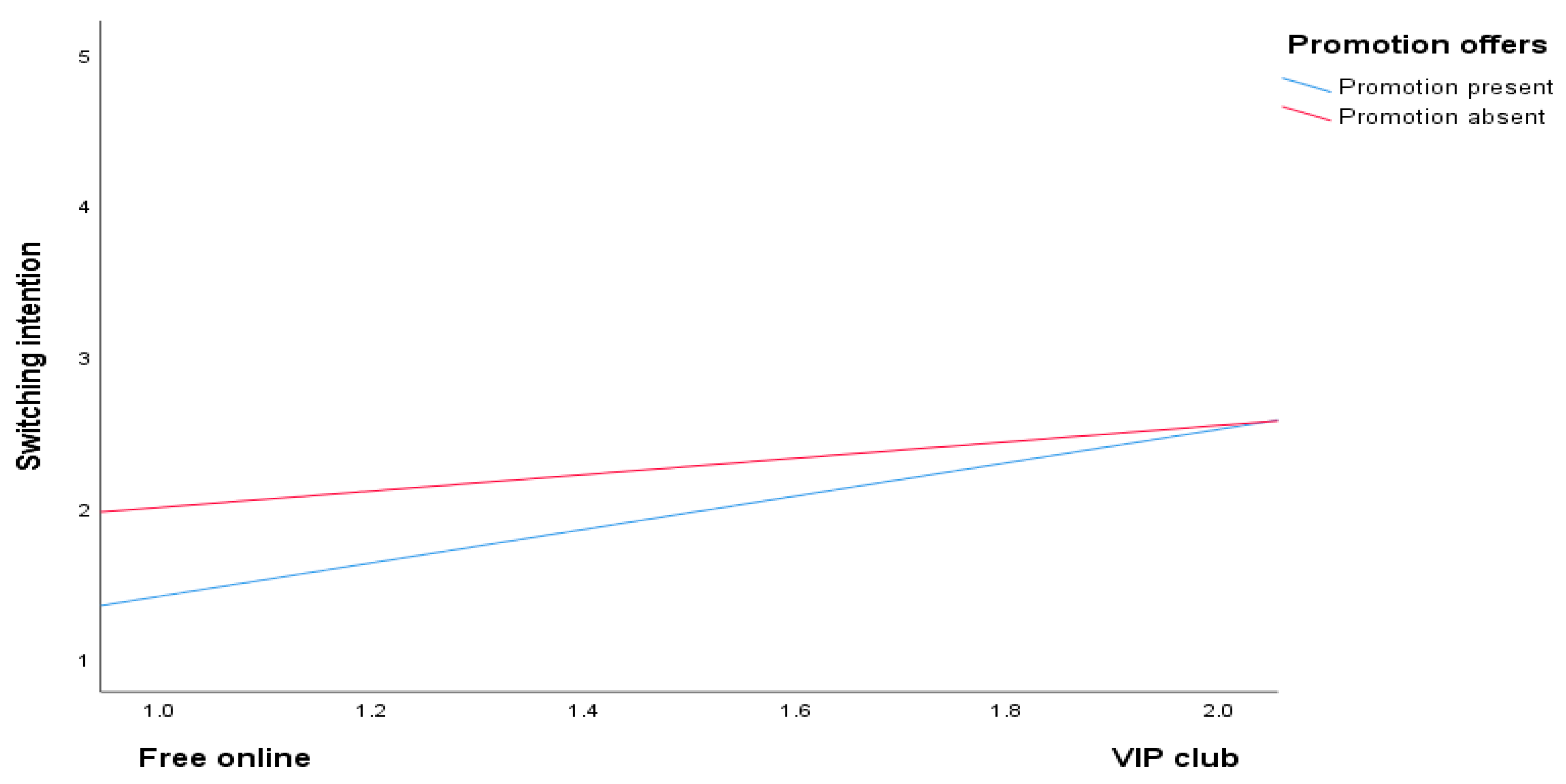

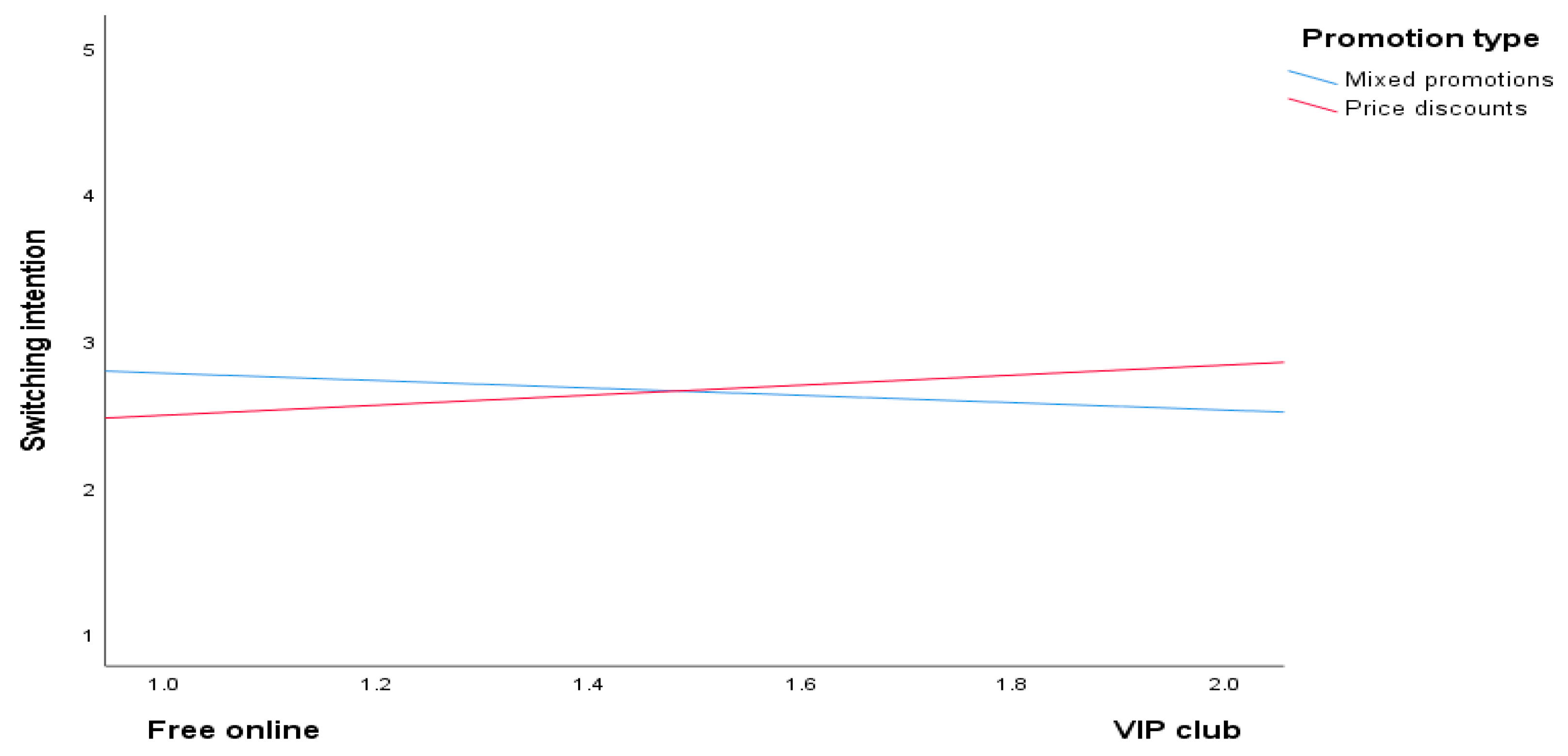

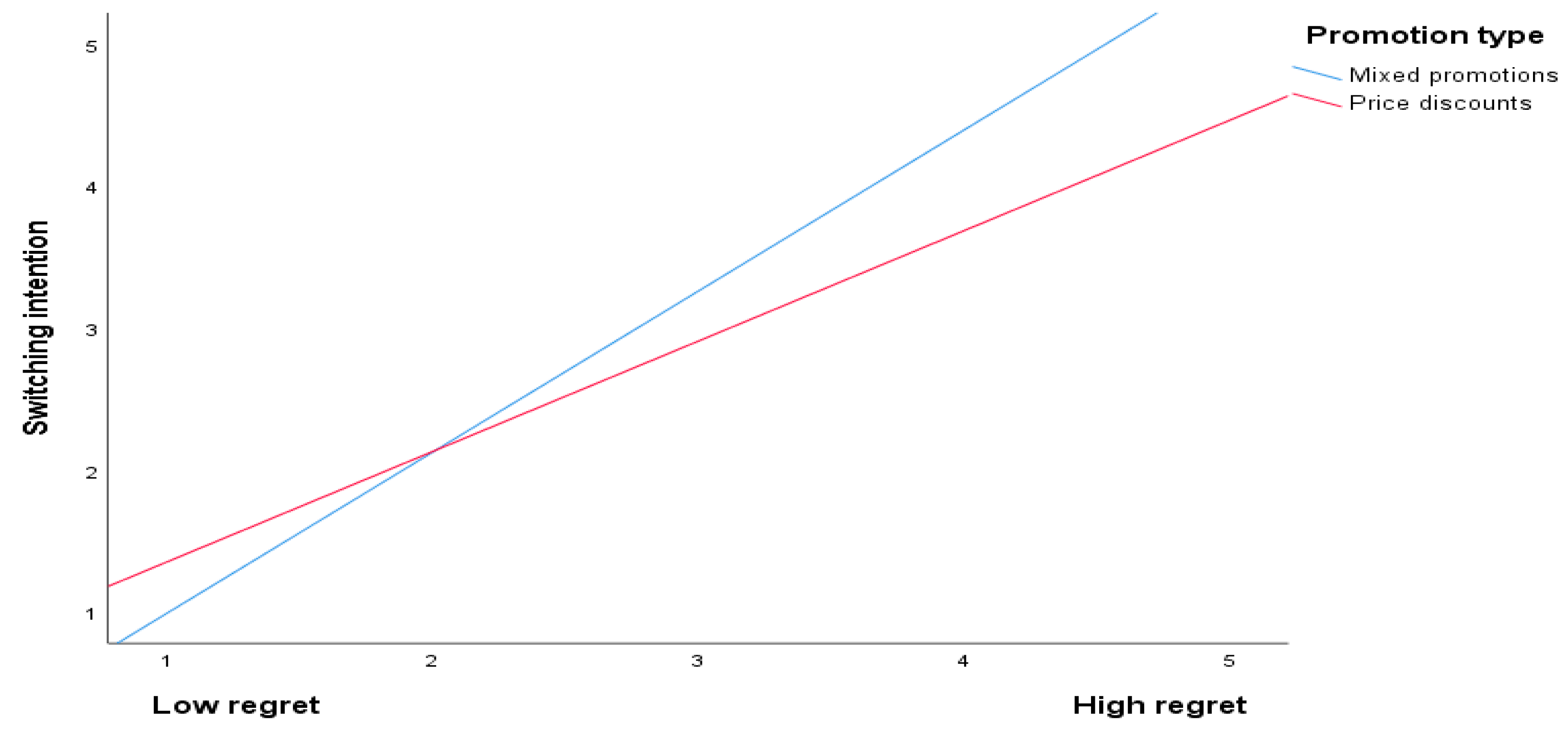

4.2. Customers’ Intentions to Switch to Alternative Hotels

5. Discussion

5.1. Summary of Key Findings

5.2. Theoretical Implications

5.3. Practical Implications

5.4. Limitations and Directions for Future Research

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Lee, S.H.; Kim, S. Brand tourism effect in the luxury hotel industry. J. Prod. Brand Manag. 2021, 30, 90–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Šerić, M.; Mikulić, J. Building brand equity through communication consistency in luxury hotels: An impact-asymmetry analysis. J. Hosp. Tour. Insights 2020, 3, 451–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; Kim, W.G. The relationship between brand equity and firms’ performance in luxury hotels and chain restaurants. Tour. Manag. 2005, 26, 549–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noone, B.M.; Lin, M.S. Scarcity-based price promotions: How effective are they in a revenue management environment? J. Hosp. Tour. Res. 2020, 44, 883–907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.; Jang, S. Did I get the best discount? Counterfactual thinking of tourism products. J. Travel Res. 2018, 57, 17–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, W.; Zhang, L.; Mattila, A.S. Luxe for less: Do consumers react to luxury hotel price promotions? The moderating role of consumers’ need for status. Cornell Hosp. Q. 2016, 57, 82–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarwar, M.A.; Awang, Z.; Habib, M.D.; Nasir, J.; Hussain, M. Why did I buy this? Purchase regret and repeat purchase intentions: A model and empirical application. J. Public Aff. 2022, 22, e2357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Min, H.; Min, H. Competitive benchmarking of Korean luxury hotels using the analytic hierarchy process and competitive gap analysis. J. Serv. Mark. 1996, 10, 58–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, M.; Lee, S.A. Do customers care about types of hotel service recovery efforts? An example of customer-generated review sites. J. Hosp. Tour. Technol. 2017, 8, 5–18. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, H.; Kim, W.G.; An, J.A. The effect of consumer-based brand equity in firms’ financial performance. J. Consum. Mark. 2003, 20, 335–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M.; Rodríguez-Serrano, M.A.; Lambkin, M. Brand equity and firm performance: The complementary role of corporate social responsibility. J. Brand Manag. 2019, 26, 691–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, Y.; Tang, L.; Luo, Y. Two decades of research on luxury hotels: A review and research agenda. J. Qual. Assur. Hosp. Tour. 2016, 17, 151–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohsin, A.; Lockyer, T. Customer perceptions of service quality in luxury hotels in New Delhi, India: An exploratory study. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2010, 22, 160–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotler, P.; Keller, K. Marketing Management, 15th ed.; Pearson Education: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Montaner, T.; de Chernatony, L.; Buil, I. Consumer response to gift promotions. J. Prod. Brand Manag. 2011, 20, 101–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sokolova, T.; Li, Y. Mix or match? Consumer spending decisions in conditional promotions. J. Consum. Psychol. 2021, 31, 91–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahneman, D.; Tversky, A. Prospect theory: An analysis of decision under risk. Econometrica 1979, 47, 263–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palazon, M.; Delgado-Ballester, E. Effectiveness of price discounts and premium promotions. Psychol. Mark. 2009, 26, 1108–1129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunes, J.C.; Park, C.W. Incommensurate resource: Not just more of the same. J. Mark. Res. 2003, 40, 26–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, G.W.; Hawkins, S.A. Strategy compatibility, scale compatibility, and the prominence effect. J. Exp. Psychol. Hum. Percept. Perform. 1993, 19, 580–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinha, I.; Smith, M.F. Consumers’ perceptions of promotional framing of price. Psychol. Mark. 2000, 17, 257–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeelenberg, M.; Pieters, R. Comparing service delivery to what might have been: Behavioral responses to regret and disappointment. J. Serv. Res. 1999, 2, 86–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davvetas, V.; Diamantopoulos, A. Regretting your brand-self? The moderating role of consumer-brand identification on consumer responses to purchase regret. J. Bus. Res. 2017, 80, 218–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bui, M.; Krishen, A.S.; Bates, K. Modeling regret effects on consumer post-purchase decisions. Eur. J. Mark. 2011, 45, 1068–1090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, K.A. A regret theory approach to assessing consumer satisfaction. Mark. Lett. 1997, 8, 229–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsiros, M.; Mittal, V. Regret: A model of its antecedents and consequences in consumer decision making. J. Consum. Res. 2000, 26, 401–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, D.; Mattila, A.S.; Bai, B. Restaurant membership fee and customer choice: The effects of sunk cost and feelings of regret. Hosp. Manag. 2007, 26, 687–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landman, J.; Vandewater, A.A.; Stewart, A.J.; Malley, J.E. Missed opportunities: Psychological ramifications of counterfactual thought in midlife women. J. Adult Dev. 1995, 2, 87–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janis, I.; Mann, L. Decision Making: A Psychological Analysis of Conflict, Choice and Commitment; Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, S.H.; Cotte, J. Post-purchase consumer regret: Conceptualization and development of the PPCR scale. Adv. Consum. Res. 2009, 36, 456–462. [Google Scholar]

- Dincer, M.; Alrawadieh, Z. Negative word of mouth in the hotel industry: A content analysis of online reviews on luxury hotels in Jordan. J. Hosp. Mark. Manag. 2017, 26, 785–804. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, S.H.; Kim, M.J.; Kim, D. The effect of Airbnb users’ regret on dissatisfaction and negative behavioral intention. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 2001002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grant, A.W.; Schlesinger, L.A. Realize your customer’s full profit potential. Harv. Bus. Rev. 1995, 73, 59–72. [Google Scholar]

- Heskett, J.L.; Sasser, W.E.; Schlesinger, L.A. The Service Profit Chain; Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Keaveney, S.M. Customer switching behavior in service industries: An exploratory study. J. Mark. 1995, 59, 71–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, H.; Kim, W.; Hyun, S.S. Switching intention model development: Role of service performance, customer satisfaction, and switching barriers in the hotel industry. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2011, 30, 619–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coulter, K.S. Enough is enough! Or is it? Factors that impact switching intentions in extended travel service transactions. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2009, 26, 144–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coulter, R.A.; Ligas, M. The long good-bye: The dissolution of customer-service provider relationships. Psychol. Mark. 2000, 17, 669–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, C.; Galliers, R.; Shin, N.; Ryoo, J.; Kim, J. Factors influencing internet shopping value and customer repurchase intention. Electron. Commer. Res. Appl. 2012, 11, 374–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryu, K.; Han, H. New or repeat customers: How does physical environment influence their restaurant experience? Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2011, 30, 599–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robertson, T.S.; Courtney, P. Why customer loyalty programs can backfire. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2021, 99, 21–24. [Google Scholar]

- Wendlandt, M.; Schrader, U. Consumer reactance against loyalty programs. J. Consum. Mark. 2007, 24, 293–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brehm, J. A Theory of Psychological Reactance; Academic Press: New York, NY, USA, 1966. [Google Scholar]

- Clee, M.; Wicklund, R. Consumer behavior and psychological reactance. J. Consum. Res. 1980, 6, 389–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-García, I.; Currás-Pérez, R. Effects of dissatisfaction in tourist services: The role of anger and regret. Tour. Manag. 2011, 32, 1397–1406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scherer, K.R.; Schorr, A.; Johnstone, T. Appraisal Processes in Emotion: Theory, Methods, Research; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Leung, X.Y.; Cai, R. How pandemic severity moderates digital food ordering risks during COVID-19: An application of prospect theory and risk perception framework. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2021, 47, 497–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasiry, J.; Popescu, I. Advance selling when consumers regret. Manag. Sci. 2012, 58, 1160–1177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davvetas, V.; Diamantopoulos, A. Should have I bought the other one? Experiencing regret in global versus local brand purchase decisions. J. Int. Mark. 2018, 26, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bozkurt, S.; Gligor, D. Customers’ behavioral responses to unfavorable pricing errors: The role of perceived deception, dissatisfaction and price consciousness. J. Consum. Mark. 2019, 36, 760–771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dholakia, U.M. How Businesses Fare with Daily Deals as They Gain Experience: A Multi-Time Period Study of Daily Deal Performance. 2012. Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=2091655 (accessed on 12 March 2022).

- Pan, H.; Ha, H. The moderating role of mobile promotion during current and subsequent purchasing occasions: The case of restaurant delivery services. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2022, 34, 601–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swaminathan, S.; Bawa, K. Category-specific coupon proneness: The impact of individual characteristics and category-specific variables. J. Retail. 2005, 81, 205–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanford, S.; Hwang, E.; Baloglu, S. Evaluation of reward programs based on member preferences and perceptions of fairness. J. Hosp. Mark. Manag. 2018, 27, 106–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, Y.; Ha, H. The role of online review in restaurant selection intentions: A latent growth modeling approach. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2023, 111, 103483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossiter, J.R. The C-OARSE procedure for scale development in marketing. Int. J. Res. Mark. 2002, 19, 305–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sloot, L.M.; Verhoef, P.C. The impact of brand delisting on store switching and brand switching intentions. J. Retail. 2008, 84, 281–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, A.F. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach, 2nd ed.; The Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Hayes, A.F. Partial, conditional, and moderated moderated mediation: Quantification, inference, and interpretation. Commun. Monogr. 2018, 85, 4–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, L.; Zhang, W.; Wang, X.; Liang, S. Moderating effects of time pressure on the relationship between perceived value and purchase intention in social E-commerce sales promotion: Considering the impact of product involvement. Inf. Manag. Basic Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2019, 56, 317–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tykocinski, O.E.; Pittman, T.S. Product aversion following a missed opportunity: Price contrast or avoidance of anticipated regret? Basic Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2001, 23, 149–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, H.; Gu, Z. The effect of different price presentations on consumer impulse buying behavior: The role of anticipated regret. Am. J. Ind. Bus. Manag. 2015, 5, 53489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K.S.; Kim, S.Y. A study on the current customer’s defection due to promotions focused on new customer acquisition. J. Korean Oper. Res. Manag. Sci. Soc. 2007, 32, 105–124. [Google Scholar]

- Jang, Y.J.; Cho, S.; Kim, W.G. Effect of restaurant patron’s regret and disappointment on dissatisfaction and behavioral intention. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2013, 30, 431–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Namkung, Y.; Jang, S. Service failure in restaurants: Which stage pf service failure is the most critical? Cornell Hosp. Q. 2010, 51, 323–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagozzi, R.P. The self-regulation of attitudes, intentions, and behavior. Soc. Psychol. Q. 1992, 55, 178–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garnefeld, I.; Böhm, E.; Klimke, L.; Oestreich, A. I thought it was over, but now it is back: Customer reactions to ex post time extensions of sales promotions. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2018, 46, 1133–1147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabler, C.B.; Landers, V.M.; Reynolds, K.E. Purchase decision regret: Negative consequences of the steadily increasing discount strategy. J. Bus. Res. 2017, 76, 201–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, E.; Lisboa, I.; Eugénio, T. The financial performance of family versus non-family firms operating in nautical tourism. Sustainability 2022, 14, 1693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.T.; Wong, I.A.; Tseng, T.; Chang, A.W.; Phau, I. Applying consumer-based brand equity in luxury hotel branding. J. Bus. Res. 2017, 81, 192–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, E.; Lisboa, I.; Crespo, C.; Moreira, J.; Eugenio, T. Evaluating Economic Sustainability of Nautical Tourism through Brand Equity and Corporate Performance; Springer Nature: Singapore, 2022; pp. 105–118. [Google Scholar]

| Coefficient (t-Value) | LLCI/ULCI | |

|---|---|---|

| Membership type | 0.28 (2.08 *) | 0.0692/2.4366 |

| Promotional offer | 0.30 (1.99 *) | 0.0184/2.6230 |

| Membership type × Promotional offer (H1) | −0.12 (−0.07, ns) | −1.1443/0.3343 |

| Membership type | −0.13 (−1.55, ns) | −3.6944/0.4343 |

| Promotional offer | −0.18 (−1.88 *) | −3.5565/−0.2355 |

| Membership type × Promotional offer (H3) | 0.26 (2.29 *) | 0.1796/2.3554 |

| Coefficient (t-Value) | LLCI/ULCI | |

|---|---|---|

| Membership type | 0.25 (3.02 **) | 0.5827/2.7534 |

| Promotional offer | 0.19 (1.92 *) | 0.0432/2.3490 |

| Membership type × Promotional offer (H2) | −0.12 (−1.64, ns) | −1.2405/0.1152 |

| Membership type | −0.35 (−3.84 **) | −2.6024/−0.9316 |

| Promotional offer | −0.08 (−1.13, ns) | −1.8957/1.2888 |

| Membership type × Promotional offer (H4) | 0.20 (1.98 *) | 0.5265/2.4481 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhi, L.; Ha, H.-Y. Do New Luxury Hotel Promotions Harm Member Customers? Sustainability 2023, 15, 8385. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15108385

Zhi L, Ha H-Y. Do New Luxury Hotel Promotions Harm Member Customers? Sustainability. 2023; 15(10):8385. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15108385

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhi, Luyao, and Hong-Youl Ha. 2023. "Do New Luxury Hotel Promotions Harm Member Customers?" Sustainability 15, no. 10: 8385. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15108385

APA StyleZhi, L., & Ha, H.-Y. (2023). Do New Luxury Hotel Promotions Harm Member Customers? Sustainability, 15(10), 8385. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15108385