Determinant of M-Banking Usage and Adoption among Millennials

Abstract

1. Introduction

- a

- What are the technological determinants of the intention to use mobile banking systems among Malaysian Millennials?

- b

- What are the significant dimensions of the perceived risk of mobile banking use among Malaysian Millennials?

- c

- What interface design qualities impact the intention to use mobile banking systems among Malaysian Millennials?

- d

- What is the relation between the intention to use and the actual use of mobile banking among Malaysian Millennials?

- e

- What is an improved model to assess mobile banking use among Malaysian Millennials?

2. Statement of Problem

3. Literature Review

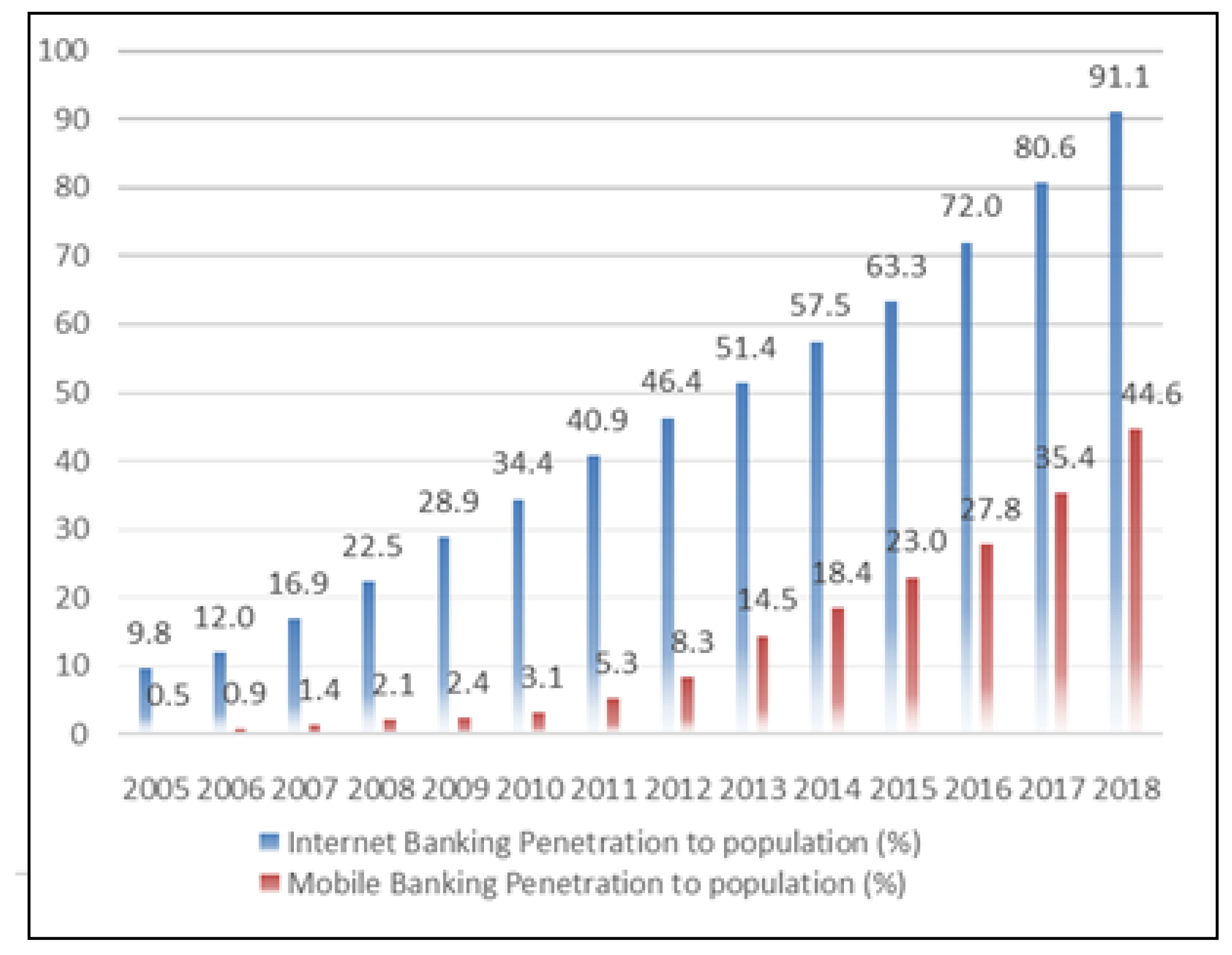

3.1. Mobile Banking in Malaysia

3.2. Millennials

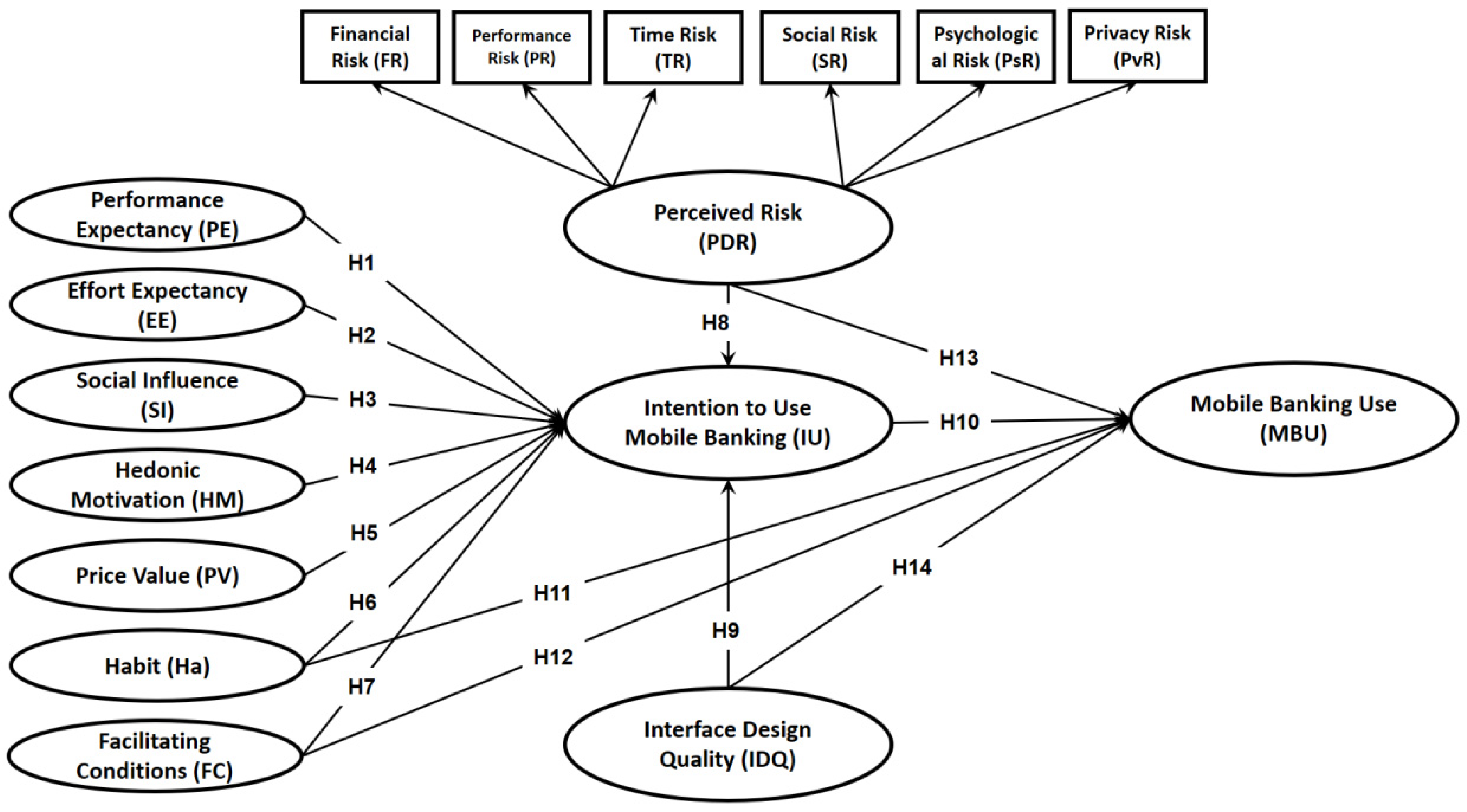

4. Theoretical Framework

4.1. Hypotheses Development

4.1.1. Intention to Use (I.U.)

4.1.2. Facilitating Conditions (F.C.)

4.1.3. Hedonic Motivation (H.M.)

4.1.4. Price Value (P.V.)

4.1.5. Performance Expectancy (P.E.)

4.1.6. Effort Expectancy (E.E.)

4.1.7. Social Influence (S.I.)

4.1.8. Habit (H.A.)

4.1.9. Perceived Risk (PDR)

4.1.10. Interface Design Quality (IDQ)

5. Method

6. Results

6.1. Reliability Test

6.2. Respondent Profile

6.3. Descriptive Statistics

6.4. Average Variance

6.5. Model Fit Examination

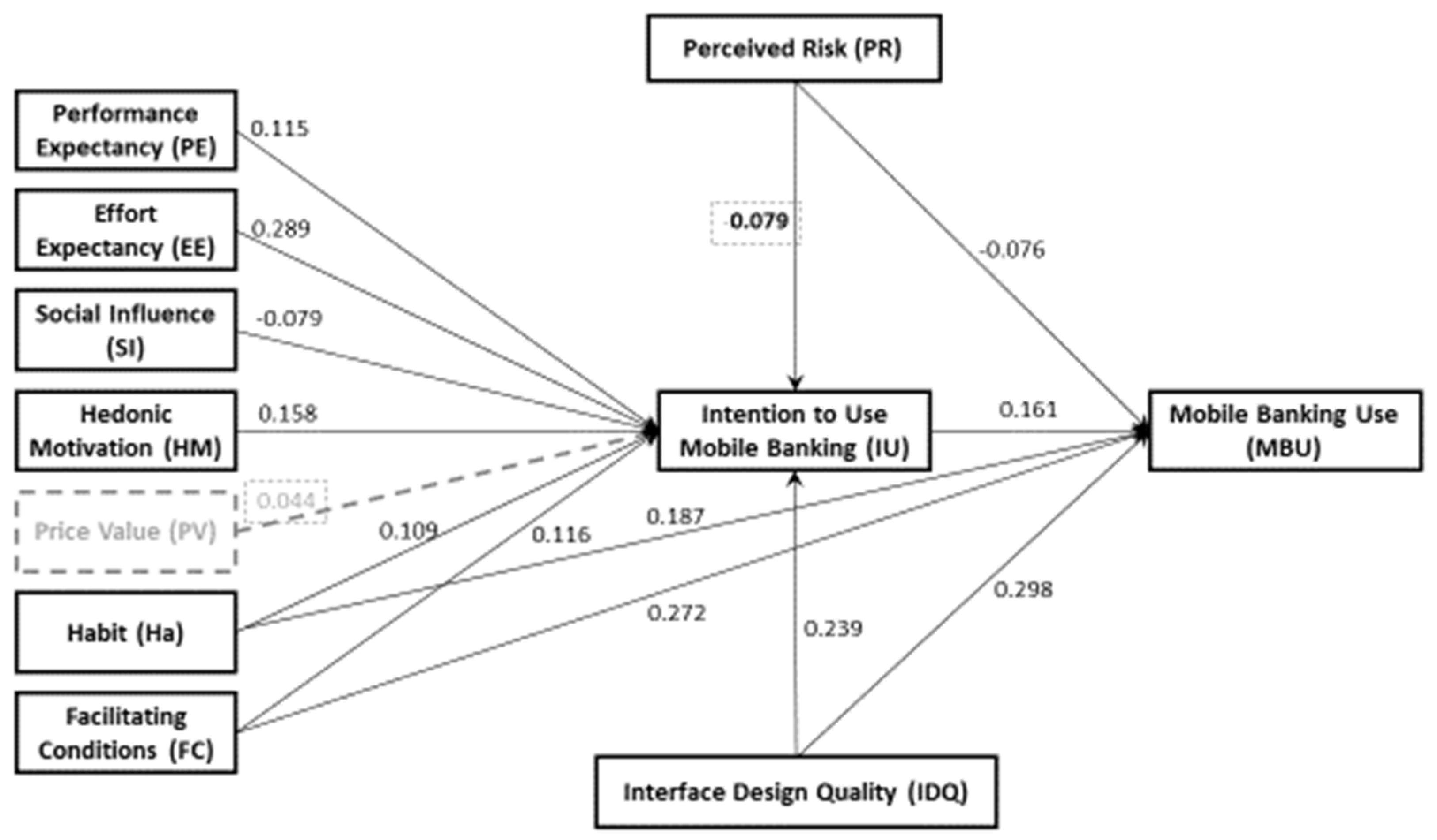

6.6. Path Coefficient

7. Discussion and Conclusions

- -

- Performance expectancy’s relationship with intention to use is significant at the degree of 5% and 1-tailed degree (T-statistics = 3.122). This relationship is marked with a substantial coefficient value of Beta = 0.115.

- -

- Efforts expectancy’s relationship with intention to use is significant at the 5% significant level and 1-tailed degree (T-statistics = 6.647). This relationship is associated with a substantial coefficient value of Beta = 0.289 and a significant satisfactory measure of adequate construct size (f2 = 0.039).

- -

- Social influence’s connection to intention to use is positive and substantial at the 5% significant level and 1-tailed degree (T-statistics = 2.029). This relationship is marked with a substantial coefficient value of Beta = −0.079 and a significant satisfactory measure of adequate construct size (f2 = 0.003).

- -

- Hedonic motivation’s relationship with intention to use is positive and substantial at the 5% significant level and 1-tailed degree (T-statistics = 4.145). This relationship is discussed along with a significant coefficient value of Beta = 0.158 and a significant satisfactory measure of adequate construct size (f2 = 0.015).

- -

- Price value’s relationship with intention to use variable is not significant at the level of 5% or even a level of 10% and 1-tailed (T-statistics = 0.33). This relation is associated with an unsatisfactory measure of the adequate construct size (f2 = 0.001).

- -

- Habit’s relationship with intention to use is positive and substantial at the 5% significant level and 1-tailed degree (T-statistics = 2.553). This relationship is discussed along with a substantial coefficient value of Beta = 0.109 and a significant satisfactory measure of adequate construct size (f2 = 0.006).

- -

- The relationship between facilitating condition and intention to use is positive and substantial at the 5% significant level and 1-tailed degree (T-statistics = 3.143). This relationship is discussed along with a substantial coefficient value of Beta = 0.116 and a significant satisfactory measure of adequate construct size (f2 = 0.008).

- (i)

- Minimise the cognitive load for the user.

- (ii)

- Keep the content to a minimum.

- (iii)

- Keep interface elements as simple as they can be.

- (iv)

- Look for alternatives for anything that requires user effort.

- (v)

- Divide long tasks into subtasks.

- (vi)

- Use easy and familiar screens.

- (i)

- Conduct campaigns and provide transparent information on the security policies used to increase users’ awareness of mobile banking use.

- (ii)

- Use recent security approaches and provide users with the information to use them.

- (iii)

- The risk dimensions include performance and time risk; therefore, an excellent interface design would help deal with those dimensions.

8. Recommendations for Future Research

9. Patent

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kwateng, K.O.; Atiemo, K.A.; Appiah, C. Acceptance and use of mobile banking: An application of UTAUT2. J. Enterp. Inf. Manag. 2019, 32, 118–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, A. Mobile Banking as Technology Adoption and Challenges: A Case of M-Banking in India. Int. J. Sci. Res. Publ. 2012, 2, 1–3. [Google Scholar]

- Kaur, B.; Madan, S. Factors Influencing Trust in Online Shopping: An Indian Consumer’s Perspective. Eur. J. Bus. Manag. 2013, 5, 132–138. [Google Scholar]

- David, H. Digital transformation in banks: The trials, opportunities and a guide to what is important. J. Digit. Bank. 2016, 1, 136–145. [Google Scholar]

- Markoska, K.; Ivanochko, I.; Gregus Ml., M. Mobile Banking Services—Business Information Management with Mobile Payments. In Agile Information Business; Flexible Systems Management; Kryvinska, N., Gregus, M., Eds.; Springer: Singapore, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Available online: https://fintechnews.my/wp-content/uploads/2021/05/Fintech-Report-Malaysia-2021-Fintech-News-Malaysia-x-BigPay.pdf (accessed on 9 February 2023).

- Krishanan, D.; Khin, A.A.; Low, K.; Teng, L. Attitude towards Using Mobile Banking in Malaysia: A Conceptual Framework. Br. J. Econ. Manag. Trade 2015, 7, 306–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amran, A.M.; Mohamed, I.S.; Yusuf, S.N.S. Effects of recipient behaviour towards mobile banking performance in microfinance institutions. Asia-Pac. Manag. Account. J. 2018, 13, 186–206. [Google Scholar]

- Ewe, S.Y.; Yap, S.F. Understanding the fundamental building blocks of mobile banking adoption: A qualitative approach. In Proceedings of the World Business and Economics Research Conference, Auckland, New Zealand, 10–11 December 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Low, Y.M.; Goh, C.F.; Tan, O.K.; Rasli, A. Usersâ   Loyalty towards Mobile Banking in Malaysia. J. Internet Bank. Commer. 2017, 22, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Shaikh, A.A.; Karjaluoto, H. Mobile banking adoption: A literature review. Telemat. Inform. 2014, 32, 129–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suhaimi, A.I.H.; Hassan, M.S.B.A. Determinants of Branchless Digital Banking Acceptance Among Generation Y in Malaysia. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE Conference on e-Learning e-Management and e-Services (IC3e), Langkawi, Malaysia, 21–22 November 2018; pp. 103–108. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, B.; Sun, C.; Liu, C.; Gui, C. Research on Initial Trust Model of Mobile Banking Users. J. Risk Anal. Crisis Response 2017, 7, 13–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afshan, S.; Sharif, A. Acceptance of mobile banking framework in Pakistan. Telemat. Inform. 2016, 33, 370–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, H.-F. An empirical investigation of mobile banking adoption: The effect of innovation attributes and knowledge-based trust. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2011, 31, 252–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zamzami, I.; Mahmud, M. Technology, CMobile Interface for m-Government Services: A Framework for Information Quality Evaluation. Int. J. Sci. Eng. Res. 2012, 3, 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Spelman, M.; Weinelt, B.; Shah, A. Digital Transformation of Industries: Digital Enterprise. World Economic Forum White Paper. 2016. Available online: https://www.weforum.org/reports/digital-transformation-of-industries/ (accessed on 25 September 2020).

- Sarkawi, M.N.; Shamsuddin, J.; Jaafar, A.R.; Abd Rahim, N.F. Impact of GNS on the Link between Family Satisfaction and JS. Syst. 2020, 11, 36–39. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, I.; Shin, Y.J. Fintech: Ecosystem, business models, investment decisions, and challenges. Bus. Horiz. 2018, 61, 35–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bank Negara Malaysia. Electronic Payments: Volume and Value of Transactions. 2015. Available online: http://www.bnm.gov.my/payment/statistics/pdf/02_epayment.pdf (accessed on 9 February 2023).

- Kupperschmidt, B.R. Multigeneration employees: Strategies for effective management. Health Care Manag. 2000, 19, 65–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smola, K.W.E.Y.; Sutton, C.D. Generational differences: Revisiting generational work values for the new millennium. J. Organ. Behav. 2002, 382, 363–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chi, C.G.; Maier, T.A.; Gursoy, D. Employees’ perceptions of younger and older managers by generation and job category. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2013, 34, 42–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.; Gursoy, D. Generation Effect on the Relationship between Work Engagement, Satisfaction, and Turnover Intention among US Hotel Employees. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2012, 31, 1195–1202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Twenge, J.M.; Campbell, S.M.; Hoffman, B.J.; Lance, C.E. Generational Differences in Work Values: Leisure and Extrinsic Values Increasing, Social and Intrinsic Values Decreasing. J. Manag. 2010, 36, 1117–1142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, H.-C.; Miller, P. The generation gap and cultural influence–a Taiwan empirical investigation. Cross Cult. Manag. Int. J. 2003, 10, 23–41. [Google Scholar]

- Raphelson, S. Amid the Stereotypes, Some Facts about Millennials. NPR. 2014. Available online: https://www.npr.org/2014/11/18/354196302/amid-the-stereotypes-some-facts-about-millennials (accessed on 9 February 2023).

- Asian Institute of Finance. Bridging the Knowledge Gap of Malaysia’s Millennials. 2015. Available online: http://www.aif.org.my/clients/aif_d01/assets/multimediaMS/publication/Finance_Matters_Understanding_Gen_Y_Bridging_the_Knowledge_Gap_of_Malaysias_Millennials.pdf (accessed on 9 February 2023).

- San, L.Y.; Omar, A.; Thurasamy, R. Online Purchase: A Study of Generation Y in Malaysia. Int. J. Bus. Manag. 2015, 10, 298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Lim, H. Age differences in mobile service perceptions: Comparison of Generation Y and baby boomers. J. Serv. Mark. 2008, 22, 568–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, E.; Leby Lau, J. Behavioural intention to adopt mobile banking among the millennial generation. Young Consum. 2016, 17, 18–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jambulingam, M.; Sorooshian, S.; Selvarajah, C.S. Tendency of generation Y in Malaysia to purchase online technological products. Int. Bus. Manag. 2016, 10, 134–146. [Google Scholar]

- Rahman, M.; Ismail, I.; Bahri, S. Analysing consumer adoption of cashless payment in Malaysia. Digit. Bus. 2020, 1, 100041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shams, G.; Rehman, M.A.; Samad, S.; Oikarinen, E.-L. Exploring customer’s mobile banking experiences and expectations among generations X.; Y and Z. J. Financ. Serv. Mark 2020, 25, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Featherman, M.; Fuller, M. Applying TAM to e-services adoption: The moderating role of perceived risk. In Proceedings of the 36th Annual Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences, Big Island, HI, USA, 6–9 January 2003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. The theory of planned behaviour. Organ. Behav. Hum. Process 1991, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkatesh, V.; Morris, M.G.; Davis, G.B.; Davis, F.D. User acceptance of information technology: Toward a unified view. MIS Q. 2003, 27, 425–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkatesh, V.; Thong, J.Y.L.; Xu, X. Consumer acceptance and use of information technology: Extending the unified theory of acceptance and use of technology. Theory Plan. Behav. 2012, 36, 157–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarhini, A.; El-masri, M.; Ali, M.; Serrano, A. Extending the UTAUT model to understand the customers ’ acceptance and use of internet banking in Lebanon A structural equation modeling approach. People 2016, 29, 830–849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Im, I.; Hong, S.; Kang, M.S. An international comparison of technology adoption. Inf. Manag. 2011, 48, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, C.-S. Factors Affecting Individuals to Adopt Mobile Banking: Empirical Evidence from the UTAUT Model. J. Electron. Commer. Res. 2012, 13, 104–121. [Google Scholar]

- Ali, M.; Kan, K.A.S.; Sarstedt, M. Direct and configurational paths of absorptive capacity and organizational innovation to successful organizational performance. J. Bus. Res. 2016, 69, 5317–5323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-qeisi, K.; Dennis, C.; Hegazy, A.; Abbad, M. How Viable Is the UTAUT Model in a Non-Western Context? Int. Bus. Res. 2015, 8, 204–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mostafa, A.A.N.; Eneizan, B. Factors Affecting Acceptance of Mobile Banking in Developing Countries. Int. J. Acad. Res. Bus. Soc. Sci. 2018, 8, 340–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farah, M.F.; Hasni, M.J.S.; Abbas, A.K. Mobile-banking adoption: Empirical evidence from the banking sector in Pakistan. Int. J. Bank Mark. 2018, 36, 1386–1413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, J. Investigating the Determinants Impacting Adoption of Mobile Banking: Evidence from Jammu and Kashmir. J. Internet Bank. Commer. 2022, 27, 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Mehra, A.; Rajput, S.; Paul, J. Determinants of adoption of latest version smartphones: Theory and evidence. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2022, 175, 121410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baabdullah, A.M.; Alalwan, A.A.; Rana, N.P.; Kizgin, H.; Patil, P. Consumer use of mobile banking (M-Banking) in Saudi Arabia: Towards an integrated model. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2019, 44, 38–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raman, A.; Don, Y. Preservice teachers’ acceptance of learning management software: An application of the UTAUT2 model. Int. Educ. Stud. 2013, 6, 157–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kit, A.H.L.; Ni, A.H.; Badri, M.; Nur Freida, E.; Tang, K.Y. UTAUT2 influencing the behavioural intention to adopt mobile applications. Bachelor’s Thesis, Universiti Tunku Abdul Rahman, Kampar, Malaysia, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Slade, E.L.; Dwivedi, Y.K.; Piercy, N.C.; Williams, M.D. Modeling Consumers’ Adoption Intentions of Remote Mobile Payments in the United Kingdom: Extending UTAUT with Innovativeness, Ris, and University of Bristol—Explore Bristol Research. Psychol. Mark. 2015, 32, 860–873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alalwan, A.A.; Dwivedi, Y.K.; Rana, N.P. Factors influencing adoption of mobile banking by Jordanian bank customers: Extending UTAUT2 with trust. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2017, 37, 99–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gharaibeh, M.K.; Arshad, M.R.M. Determinants of intention to use mobile banking in the North of Jordan: Extending UTAUT2 with mass media and trust. J. Eng. Appl. Sci. 2018, 13, 2023–2033. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, S. Understanding Undergraduate Students’ Adoption of Mobile Learning Model: A Perspective of the Extended UTAUT2. J. Converg. Inf. Technol. 2013, 8, 969–979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phonthanukitithaworn, C.; Sellitto, C.; Fong, M.W.L. User intentions to adopt mobile payment services: A study of early adopters in Thailand. J. Internet Bank. Commer. 2015, 20, 1–29. [Google Scholar]

- Davis, F.F.D. Perceived Usefulness, Perceived Ease of Use, and User Acceptance of Information Technology. MIS Q. 1989, 13, 319–340. Available online: http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.2307/249008 (accessed on 9 February 2023). [CrossRef]

- Abbas, S.K.; Hassan, H.A.; Asif, J.; Ahmed, B.; Hassan, F.; Haider, S.S. Integration of TTF, UTAUT, and ITM for mobile Banking Adoption. Int. J. Adv. Eng. Manag. Sci. 2018, 4, 375–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Changchit, C.; Lonkani, R. Mobile Banking: Exploring Determinants of Its Adoption. J. Organ. Comput. Electron. Commer. 2017, 27, 239–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, A.P.; Khan, S.; Xiang, I.A.R. Factors influencing consumer intentions to adopt online banking in Malaysia. Bus. Econ. Rev. 2017, 9, 101–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maduku, D.K. Customer acceptance of mobile banking services: Use experience as moderator. Soc. Behav. Personal. Int. J. 2017, 45, 893–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.J.; Yan Huang, S.; Chiu, A.A.; Pai, F.C. The ERP system impact on the role of accountants. Ind. Manag. Data Syst. 2012, 112, 83–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fakhri, F. A Study on Factors Affecting the Behavioral Intention to Use Mobile Apps in Malaysia. Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3090753 (accessed on 19 December 2017). [CrossRef]

- AbuShanab, E.; Pearson, J.M. Internet banking in Jordan. J. Syst. Inf. Technol. 2007, 9, 78–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khasawneh, M.H.A.; Hujran, O.; Abdrabbo, T. A quantitative examination of the factors that influence users’ perceptions of trust towards using mobile banking services. Int. J. Internet Mark. Advert. 2018, 12, 181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, T.; Lu, Y.; Wang, B. Integrating TTF and UTAUT to explain mobile banking user adoption. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2010, 26, 760–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Limayem, M.; Hirt, S.G.; Cheung, C.M.K. How Habit Limits the Predictive Power of Intention: The Case of Information Systems. MIS Quarterly 2007, 31, 705–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chao, C.-M. Factors Determining the Behavioral Intention to Use Mobile Learning: An Application and Extension of the UTAUT Model. Front. Psychol. 2019, 10, 1652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moorthy, K.; Suet Ling, C.; Weng Fatt, Y.; Mun Yee, C.; Yin, K.; Chong, E.; Kok Wei, L. Barriers of mobile commerce adoption intention: Perceptions of generation X in Malaysia. J. Theor. Appl. Electron. Commer. Res. 2017, 12, 37–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chavali, K.; Kumar, A. Adoption of Mobile Banking and Perceived Risk in GCC. Banks Bank Syst. 2018, 13, 72–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richard, E.; Mandari, E. Factors influencing usage of mobile banking services: The case of ilala district in tanzania. Orsea J. 2018, 7, 42–54. [Google Scholar]

- Alzaidi, M.S. Exploring the Determinants of Mobile Banking Adoption in the Context of Saudi Arabia. Int. J. Cust. Relatsh. Mark. Manag. 2022, 13, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mutahar, A.M.; Daud, N.M.; Ramayah, T.; Isaac, O.; Aldholay, A.H. The effect of awareness and perceived risk on the technology acceptance model (TAM): Mobile banking in Yemen. Int. J. Serv. Stand. 2018, 12, 180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shuhidan, S.M.; Hamidi, S.R.; Saleh, I.S. Perceived Risk towards Mobile Banking: A case study of Malaysia Young Adulthood. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2017, 226, 012115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bharati, P.; Chaudhury, A. An empirical investigation of decision-making satisfaction in web-based decision support systems. Decis. Support Syst. 2004, 37, 187–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Everard, A.; Galletta, D.F. How presentation flaws affect perceived site quality, trust, and intention to purchase from an online store. J. Manag. Inf. Syst. 2005, 22, 56–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Otaibi, S.; Aljohani, N.R.; Hoque, M.R.; Alotaibi, F.S. The Satisfaction of Saudi Customers Toward Mobile Banking in Saudi Arabia and the United Kingdom. J. Glob. Inf. Manag. 2018, 26, 85–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nanda, P.; Bos, J.; Kramer, K.; Hay, C.; Ignacz, J. Effect of smartphone aesthetic design on users’ emotional reaction: An empirical study. TQM J. 2018, 20, 348–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cyr, D.; Head, M.; Ivanov, A. Design aesthetics leading to m-loyalty in mobile commerce. Inf. Manag. 2006, 43, 950–963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivanova, A.; Kim, J.Y. Acceptance and use of mobile banking in Central Asia: Evidence from modified UTAUT model. J. Asian Financ. Econ. Bus. 2022, 9, 217–227. [Google Scholar]

- Knapp, H. Introductory Statistics Using SPSS; Sage Publications: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Baptista, G.; Oliveira, T. Understanding mobile banking: The unified theory of acceptance and use of technology combined with cultural moderators. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2015, 50, 418–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.J.; Hult, G.T.M.; Ringle, C.; Sarstedt, M. A Primer on Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM). Long Range Plan. 2014, 46, 184–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | Definition |

|---|---|

| Financial Technology | The portmanteau “Fintech”, conceived by a New York banker in 1972, refers to the intersection of technology and financial services. Financial technology or Fintech refers to the use of technology to facilitate the financial process; this could include electronic wallets, cash cards, mobile banking, and much more [19]. |

| Millennials | The first use of the phrase was in August 1993 in an Ad Age editorial. According to the characterisation, Ad Age begins to make use of 1982 as a starting birth year [26]. This particular study describes Generation Y, which is known as Millennials, as all of the individuals that were born during the time period starting from 1980 and finishing in 2000. |

| Mobile Banking Use | Mobile banking use is the actual use or behavioural use of the system. In a different model, such as UTAUT and TAM, behaviour is defined as the user’s act of performing an action [81]. This study follows the agreed definition and defines mobile banking use as the actual act of performing financial transactions via the mobile banking application. |

| Behavioural Intention | Ref. [56] defined behavioural intention as the degree to which a person is prompt to accomplish a certain behaviour. The behaviour purpose is identified as the extent to which someone is prepared to perform a certain behaviour, as well as regularly trying to deal with a preferred behaviour [36]. This particular study uses the agreed characterisation and also defines a behavioural goal as the ready fitness level towards executing some planned action. |

| Performance Expectancy | Ref. [37] defined performance approval as the degree to which a particular person thinks that utilizing an information product will aid him or maybe her to benefit from efficiency. This study defines performance expectancy as the expectation level of system performance in terms of usefulness, quickness, productivity, and benefits. |

| Effort Expectancy | Ref. [37] defined energy expectancy as the level of ease that people believe they are going to have when working with an information system. This study defines effort expectancy as the expectation level of efforts needed to use the system in terms of ease of use, clear interaction, and ease to become an expert with the system. |

| Social Influence | Ref. [36] principle of reasoned motion (TRA) characterized subjective norms as the perceived outside pressures to utilize (or not use) a product. The construct of subjective majority refers to whether pupils encounter some public impact toward their appropriation and use of an online learning system. This particular study uses the agreed characterisation and defines community impact as the pressure that is experienced by the customer to make use of the system by friends, family, or maybe key others. |

| Facilitating Condition | Ref. [37], facilitating conditions (FC) are defined as “the degree to which an individual believes that an organisational and technical infrastructure exists to support use of the system”. From the term facility, facilitating condition is associated with the availability of all the required resources for making a system working, active, and providing the desired services. This study follows the agreed definition and defines facilitating condition as the consumers’ perception that all the resources required to make mobile banking active are available. |

| Hedonic Motivation | Hedonic motivation (HM) is actually described as the fun or maybe pleasure derived from making use of a technology, and it has been found playing a crucial job in figuring out know-how validation and how to make use of a technology) [38]. This study defines hedonic motivation as the level of mobile banking user enjoyment while using the application of mobile banking. |

| Habit | Habit is defined as “a perceptual construct that reflects the results of an individual’s prior experiences” [38]. Ref. [66] defined habit as “The extent to which people tend to perform behaviours (use IS) automatically because of learning”. This study defines habit in mobile learning as the user auto-behaviour for using a mobile application whenever he performs the action of financial transaction. |

| Price Value | Ref. [38] mentioned that price value (PV) is defined as “consumers’ cognitive tradeoff between the perceived benefits of the applications and the monetary cost for using them”. Unlike the way in which organisations buy and use the technology, in consumer use contexts, consumers usually have to pay all the cost of using a technology. This study defines price value in mobile banking as the user evaluation of whether the perceived benefits of bank services offered online for smartphone users deserve the cost paid or not. |

| Perceived Risk | According to [35], perceived risk is defined as “the potential for loss in the pursuit of a desired outcome of using an e-service”. They identified seven types of risks, which are related to seven possible potential damages, namely performance, privacy, time, financial, psychological, social, and overall risk. This study defines perceived risk in mobile banking as the user perception of any potential loss as a result of using mobile banking applications and services. |

| Interface Design Quality | For this particular study, the interface design quality of mobile application refers to the contextual features of the application in terms of font size, mobile-friendly buttons, colors, and many more design qualities to make sure that the application is easy to use on mobile devices. |

| Variable | Abbreviation | Cronbach Alpha |

|---|---|---|

| Effort Expectancy | EE | 0.815 |

| Facilitating Conditions | FC | 0.719 |

| Financial Risk | FR | 0.840 |

| Hedonic Motivation | HM | 0.771 |

| Habit | Ha | 0.776 |

| Interface Design Quality | IDQ | 0.765 |

| Intention to Use Mobile Banking | IU | 0.813 |

| Mobile Banking Use | MBU | 0.866 |

| Performance Expectancy | PE | 0.874 |

| Performance Risk | PR | 0.821 |

| Price Value | PV | 0.826 |

| Psychological Risk | PsR | 0.894 |

| Privacy Risk | PvR | 0.822 |

| Social Influence | SI | 0.721 |

| Social Risk | SR | 0.846 |

| Time Risk | TR | 0.793 |

| Frequency | Percent | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 241 | 47.8 |

| Female | 263 | 52.2 | |

| Age | 18–22 Years | 141 | 28.0 |

| 23–27 Years | 129 | 25.6 | |

| 28–32 Years | 121 | 24.0 | |

| 33–37 Years | 113 | 22.4 | |

| Race | Malay | 288 | 57.1 |

| Chinese | 132 | 26.2 | |

| Indian | 75 | 14.9 | |

| Others | 9 | 1.8 | |

| The Highest Education Level | High School | 64 | 12.7 |

| Diploma | 74 | 14.7 | |

| BSc | 256 | 50.8 | |

| Post-Graduate | 108 | 21.4 | |

| Other | 2 | 0.4 | |

| Employment | Non-Working | 129 | 25.6 |

| Self-Employed | 77 | 15.3 | |

| Government Employed | 100 | 19.8 | |

| Private Employed | 198 | 39.3 | |

| Monthly Income Level | Less MYR 1500 | 170 | 33.7 |

| MYR 1500–3000 | 132 | 26.2 | |

| MYR 3001–5000 | 105 | 20.8 | |

| MYR 5001–10,000 | 69 | 13.7 | |

| Above MYR 10,000 | 28 | 5.6 | |

| Personal Use of Mobile Services | No Experience | 48 | 9.5 |

| up to 6 Months | 89 | 17.7 | |

| 6–12 Months | 54 | 10.7 | |

| 1–2 Years | 139 | 27.6 | |

| Above 2 Years | 174 | 34.5 | |

| Personal Experience with Mobile Services | Very Poor | 21 | 4.2 |

| Poor | 40 | 7.9 | |

| Good | 223 | 44.2 | |

| Very Good | 172 | 34.1 | |

| Excellent Total | 48 504 | 9.5 100.0 | |

| Variables | Min Score | Max Score | Mean Value | Std. Deviation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Performance Expectancy | 2.25 | 5 | 4.0834 | 0.63465 |

| Effort Expectancy | 2.23 | 5 | 4.167 | 0.67614 |

| Social Influence | 1.71 | 5 | 3.7606 | 0.74612 |

| Facilitating Conditions | 2.26 | 5 | 4.0822 | 0.64817 |

| Hedonic Motivation | 1.66 | 5 | 3.6759 | 0.7403 |

| Price Value | 1.76 | 5 | 3.6592 | 0.63548 |

| Habit | 1.27 | 5 | 3.5878 | 0.7549 |

| Financial Risk | 1 | 5 | 3.0175 | 0.95385 |

| Time Risk | 1 | 4.76 | 2.7815 | 0.86464 |

| Performance Risk | 1 | 4.8 | 3.0265 | 0.82246 |

| Privacy Risk | 1 | 5 | 3.1051 | 0.89675 |

| Social Risk | 1 | 5 | 3.1385 | 0.89958 |

| Psychological Risk | 1 | 4.69 | 2.6615 | 0.94168 |

| Screen and Interface Design Quality | 2.25 | 5 | 3.8424 | 0.61467 |

| Intention to Use | 2 | 5 | 3.9196 | 0.70232 |

| Mobile Banking Use | 1 | 5 | 3.5897 | 0.95162 |

| Variable | Abbreviation | AVE |

|---|---|---|

| Mobile Banking Use | MBU | 0.833 |

| Intention to Use Mobile Banking | IU | 0.762 |

| Performance Expectancy | PE | 0.670 |

| Effort Expectancy | EE | 0.728 |

| Social Influence | SI | 0.740 |

| Hedonic Motivation | HM | 0.795 |

| Price Value | PV | 0.714 |

| Habit | Ha | 0.668 |

| Facilitating Conditions | FC | 0.651 |

| Interface Design Quality | IDQ | 0.716 |

| Financial Risk | FR | 0.807 |

| Performance Risk | PR | 0.712 |

| Time Risk | TR | 0.759 |

| Social Risk | SR | 0.743 |

| Psychological Risk | PsR | 0.789 |

| Privacy Risk | PvR | 0.799 |

| Measure | Estimated Model |

|---|---|

| SRMR | 0.034 |

| d_ULS | 0.075 |

| d_G | 0.106 |

| Chi-Square | 235.986 |

| NFI | 0.910 |

| Intention to Use | Mobile Banking Use | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Q2 Original | Q2 Omitted | f2 Value | Status | Q2 Original | Q2 Omitted | f2 Value | Status | |

| Performance Expectancy | 0.603 | 0.595 | 0.008 | Neglected | ||||

| Effort Expectancy | 0.603 | 0.564 | 0.039 | Satisfactory | ||||

| Social Influence | 0.603 | 0.600 | 0.003 | Neglected | ||||

| Hedonic Motivation | 0.603 | 0.588 | 0.015 | Neglected | ||||

| Price Value | 0.603 | 0.602 | 0.001 | Neglected | ||||

| Habit | 0.603 | 0.597 | 0.006 | Neglected | 0.553 | 0.529 | 0.024 | Satisfactory |

| Facilitating Condition | 0.603 | 0.595 | 0.008 | Neglected | 0.553 | 0.502 | 0.051 | Satisfactory |

| Interface Design Quality | 0.603 | 0.571 | 0.032 | Satisfactory | 0.553 | 0.501 | 0.052 | Satisfactory |

| Perceived Risk | 0.603 | 0.598 | 0.005 | Neglected | 0.553 | 0.548 | 0.005 | Neglected |

| Intention to Use | 0.553 | 0.541 | 0.012 | Neglected | ||||

| Research Question | H | The Relation | Path Coefficient | T Statistics | p Value | Status |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RQ1 | H1 | Performance Expectancy and Intention to Use | 0.115 | 3.122 | 0.001 | Significant |

| RQ1 | H2 | Effort Expectancy and Intention to Use | 0.289 | 6.647 | 0.000 | Significant |

| RQ1 | H3 | Social Influence and Intention to Use | −0.079 | 2.029 | 0.021 | Significant |

| RQ1 | H4 | Hedonic Motivation and Intention to Use | 0.158 | 4.145 | 0.000 | Significant |

| RQ1 | H5 | Price Value and Intention to Use | 0.044 | 1.336 | 0.091 | Non-Significant |

| RQ1 | H6 | Habit and Intention to Use | 0.109 | 2.553 | 0.005 | Significant |

| RQ1 | H7 | Facilitating Condition and Intention to Use | 0.116 | 3.143 | 0.001 | Significant |

| RQ2 | H8 | Perceived Risk and Intention to Use | −0.079 | 2.706 | 0.004 | Significant |

| RQ3 | H9 | Interface Design Quality and Intention to Use | 0.239 | 6.243 | 0.000 | Significant |

| RQ4 | H10 | Intention to Use and Mobile Baking Use | 0.161 | 3.819 | 0.000 | Significant |

| RQ5 | H11 | Habit and Mobile Baking Use | 0.187 | 4.907 | 0.000 | Significant |

| RQ5 | H12 | Facilitating Condition and Mobile Baking Use | 0.272 | 6.350 | 0.000 | Significant |

| RQ5 | H13 | Perceived Risk and Mobile Baking Use | −0.076 | 2.485 | 0.007 | Significant |

| RQ5 | H14 | Interface Design Quality and Mobile Baking Use | 0.298 | 6.956 | 0.000 | Significant |

| # | Hypotheses | Status |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | H1: performance expectancy concept has a positive influence on intention to use concept. | Accepted |

| 2 | H2: Effort Expectancy concept has a positive influence on intention to use concept. | Accepted |

| 3 | H3: social influence concept has a positive influence on intention to use concept. | Accepted |

| 4 | H4: hedonic motivation concept has a positive influence on intention to use concept. | Accepted |

| 5 | H5: price value concept has a positive influence on intention to use concept. | Not Accepted |

| 6 | H6: habit concept has a positive influence on intention to use concept. | Accepted |

| 7 | H7: facilitating conditions concept has a positive influence on intention to use concept. | Accepted |

| 8 | H8: perceived risk concept has a negative influence on intention to use concept. | Accepted |

| 9 | H9: interface design quality concept has a positive influence on intention to use concept. | Accepted |

| 10 | H10: intention to use concept has a positive influence on system use concept. | Accepted |

| 11 | H11: habit concept has a positive influence on the system use concept. | Accepted |

| 12 | H12: facilitating conditions concept has a positive influence on the system use concept. | Accepted |

| 13 | H13: perceived risk concept has a negative influence on the system use concept. | Accepted |

| 14 | H14: interface design quality has a positive influence on the system use concept. | Accepted |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Al Tarawneh, M.A.; Nguyen, T.P.L.; Yong, D.G.F.; Dorasamy, M.A/P. Determinant of M-Banking Usage and Adoption among Millennials. Sustainability 2023, 15, 8216. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15108216

Al Tarawneh MA, Nguyen TPL, Yong DGF, Dorasamy MA/P. Determinant of M-Banking Usage and Adoption among Millennials. Sustainability. 2023; 15(10):8216. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15108216

Chicago/Turabian StyleAl Tarawneh, Mo’men Awad, Thi Phuong Lan Nguyen, David Gun Fie Yong, and Magiswary A/P Dorasamy. 2023. "Determinant of M-Banking Usage and Adoption among Millennials" Sustainability 15, no. 10: 8216. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15108216

APA StyleAl Tarawneh, M. A., Nguyen, T. P. L., Yong, D. G. F., & Dorasamy, M. A/P. (2023). Determinant of M-Banking Usage and Adoption among Millennials. Sustainability, 15(10), 8216. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15108216