The Presence of a Family Communal Space as a Form of Local Wisdom towards Community Cohesion and Resilience in Coastal Settlements

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Research Sites

2.2. Population and Sample

2.3. Data Collection

2.4. Data Analysis

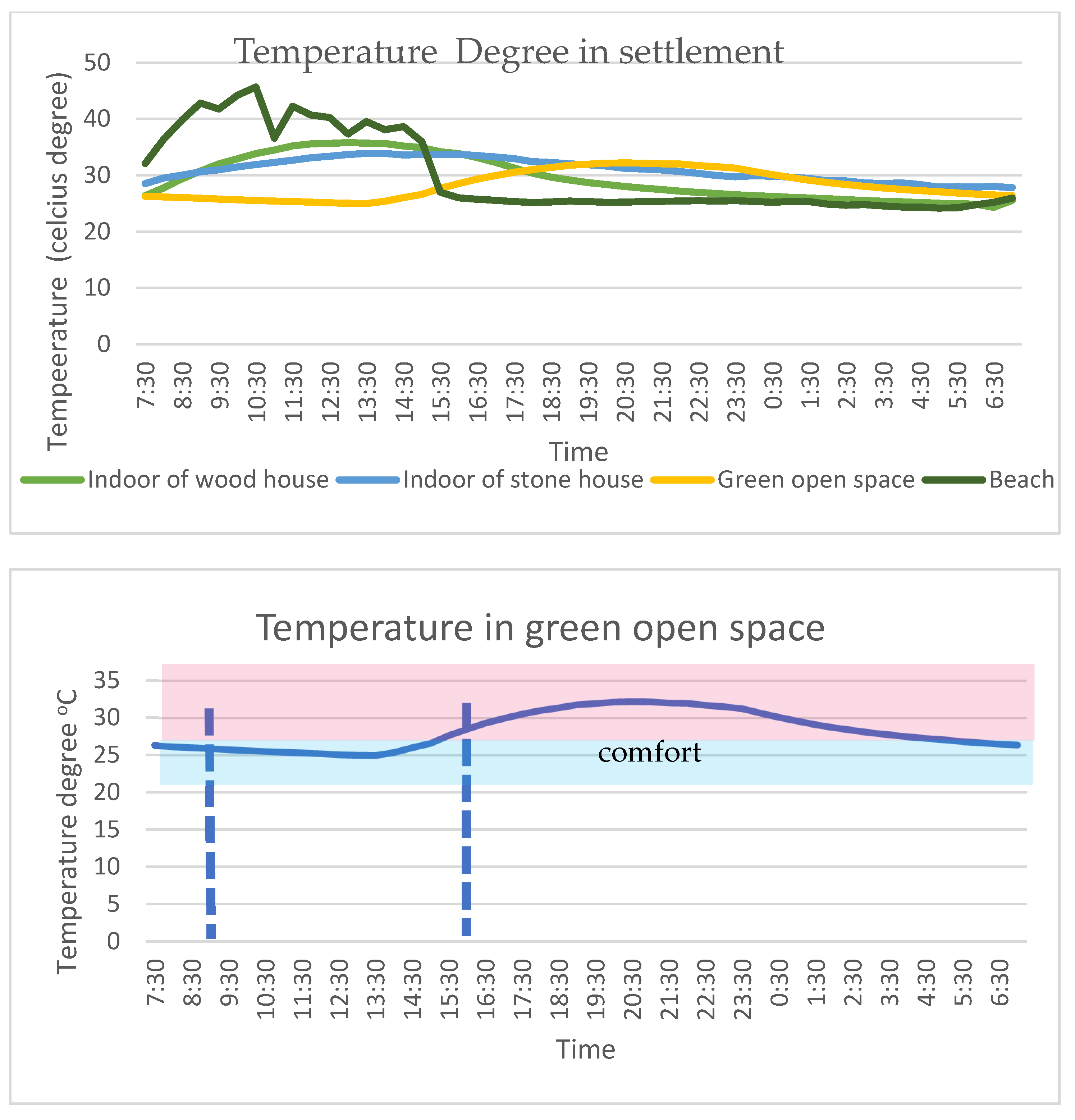

3. Results

- Pearson correlation between gender and age 0.056, gender and time duration 0.080, and gender and activity type −0.375 **;

- Pearson correlation between age and gender 0.056, age and time duration −0.155, age and activities 0.146;

- Pearson correlation between time duration and gender 0.080, time duration and age −0.155, time duration and activities −0.275 **;

- Pearson correlation between activities and gender −0.375 **, activities and age 0.146, activities and time duration −0.275 **;

- Then, based on the values of the correlation coefficient being 0.2 to <0.4, which is a relationship even though it is weak, others being >0 to <0.2, which is very weak, and the negative relationship, close to −1, it can be concluded that there is a correlation, although weak, between the type of activities and gender, and the type of activity with the time duration, Likewise, between activities and age the correlation is very weak. The type of activity is related to gender, and the type of activity is related to the duration of time spent in the room, as well as the type of activity related to age.

4. Discussion

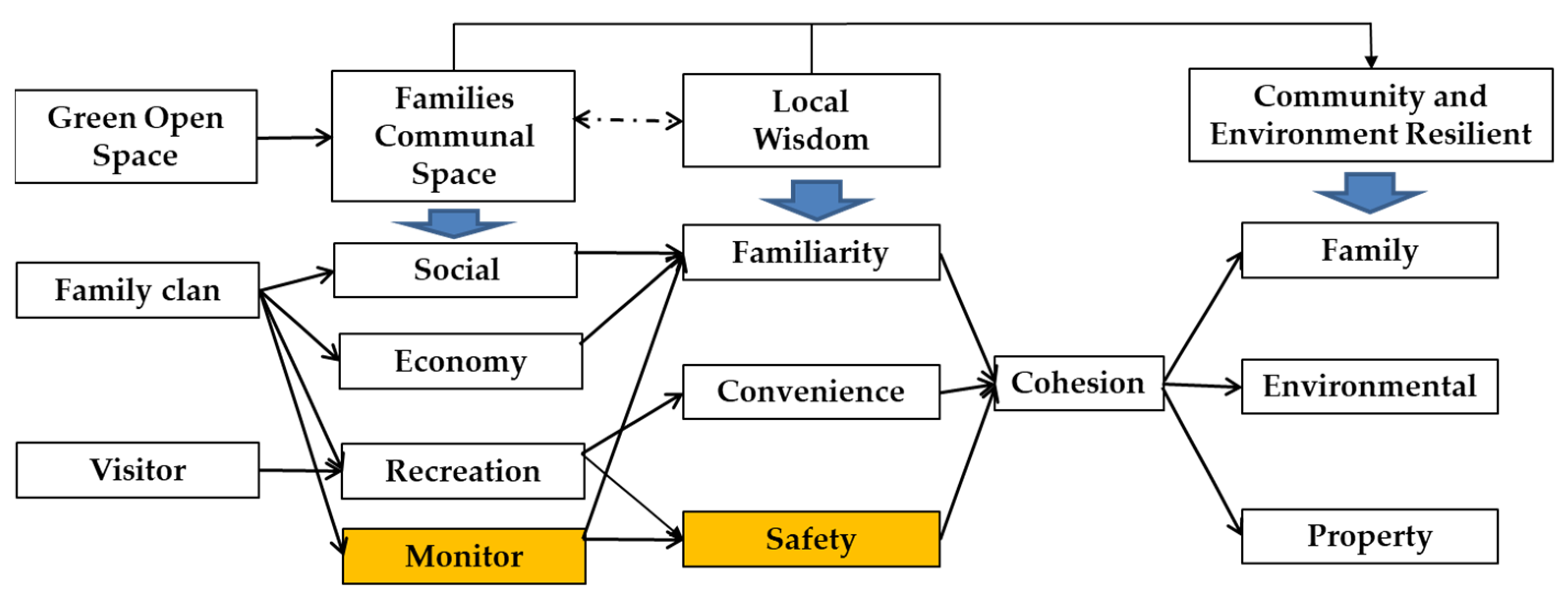

4.1. FCSs Increasing the Cohesion of Family Members

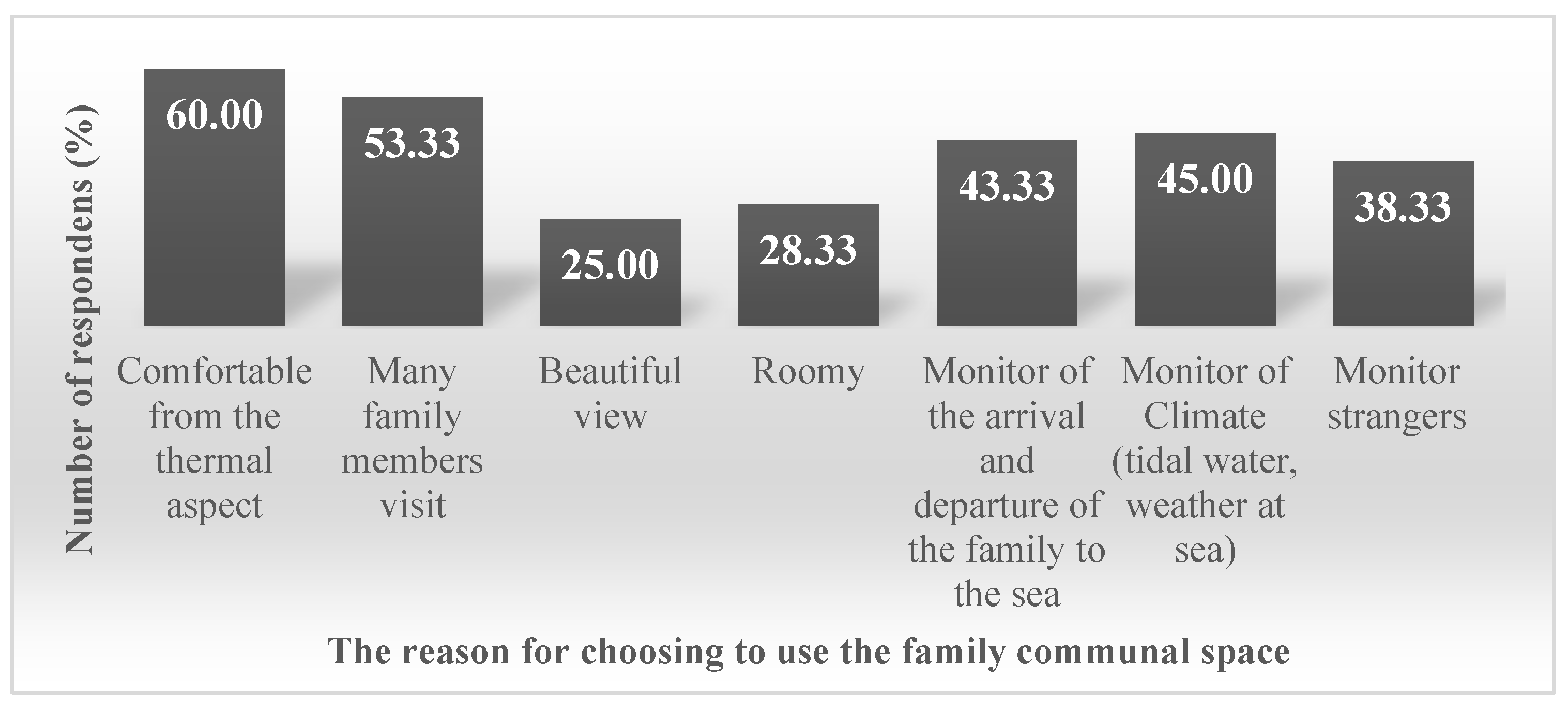

4.2. Communal Space as an Environmental and Family Control Space

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Gallacher, P. Everyday Spaces: The Potential of Neighborhood Space; Thomas Telford: London, UK, 2005; 96 pages. [Google Scholar]

- Vukmirovic, M.; Gavrilovic, S.; Stojanovic, D. The Improvement of the Comfort of Public Spaces as a Local Initiative in Coping with Climate Change. Sustainability 2019, 11, 6546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alizadeh, H.; Bork-Hüffer, T.; Kohlbacher, J.; Mohammed-Amin, R.K. The contribution of urban public space to the social interactions and empowerment of women. J. Urban Aff. 2022, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jo, Y.-I.; Lee, J.-L.; Koo, J.-H. Effect of Physical Environment and Programs on the Social Interaction of Youth Space Users in Seoul in the Case of Pilot Projects. Sustainability 2018, 10, 4515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aelbrecht, P.; Stevens, Q.; Nisha, B. Public Space Design and Social Cohesion: An International Comparison; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2018; p. 33. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.; Chen, G.; He, Y.; Jiang, X.; Xue, C. Social Interaction in Public Spaces and Well-Being among Elderly Women: Towards Age-Friendly Urban Environments. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farida, N. Effects of outdoor shared spaces on social interaction in a housing estate in Algeria. Front. Archit. Res. 2013, 2, 457–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bishop, K.; Marshall, N. Social Interactions and the Quality of Urban Public Space. In Reference Module in Earth Systems and Environmental Sciences; Encyclopedia of Sustainable Technologies; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2017; Volume 2, pp. 63–70. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, J.; Ruggeri, K.; Steemers, K.; Huppert, F. Lively Social Space, Well-Being Activity, and Urban Design: Findings from a low-cost community-led public space intervention. Environ. Behav. 2016, 49, 685–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Ding, J.; Zhu, Q.; Cheng, Y.; Ma, Q.; Ji, X. The Impact of Green Open Space on Community Attachment—A Case Study of Three Communities in Beijing. Sustainability 2017, 9, 560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chitrakar, R. Meaning of public space and sense of community: The case of new neighborhoods in the Kathmandu Valley. March 2016. Int. J. Archit. Res. Arcnet-IJAR 2016, 10, 213–227. [Google Scholar]

- Gregory, D.; Johnston, R.; Pratt, G.; Watts, M.; Whatmore, S. (Eds.) The Dictionary of Human Geography; John Wiley & Sons: Malden, MA, USA, 2011; p. 1072. [Google Scholar]

- Oliver, R.G.; Sinenart, S. Neighborhood design and sense of community: Comparing suburban neighborhoods in Houston Texas. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2009, 92, 325–334. [Google Scholar]

- Farahani, L.M. The Value of the Sense of Community and Neighbouring. Hous. Theory Soc. 2016, 33, 357–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suwignyo, A. Gotong royong as social citizenship in Indonesia, 1940s to 1990s. J. Southeast Asian Stud. 2019, 50, 387–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Local Government Association. Community Cohesion Is an Action Guide; LGA Publications: London, UK, 2004; p. 96.

- Manca, A.R. Social Cohesion. Encyclopedia of Quality of Life and Well-Being Research; Springer Science + Business Media: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2014; pp. 6026–6028. [Google Scholar]

- Salimi, M.; Foroutan, M.; Naghdi, A. Analyzing Social Cohesion in Open Spaces of Multiethnic Poor Neighborhoods: A Grounded Theory Study. J. Archit. Urban. 2019, 43, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sari, S.R.; Suwarno, N.; Nuryanti, W.; Diananta, P. The Role of Social Cohesion to Reduce Social Conflict in Tourist Destination Area. KOMUNITAS Int. J. Indones. Soc. Cult. 2014, 6, 294–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fennelly, L.J.; Perry, M.A. Chapter Defensible Space Theory and CPTED. In CPTED and Traditional Security Countermeasures 150 Things You Should Know, 1st ed.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2018; p. 3. [Google Scholar]

- Ye, B.; Hu, J.; Im, H.; Liu, M.; Wang, X.; Yang, Q. Family Cohesion and Sleep Disturbances During COVID-19: The Mediating Roles of Security and Stress. Int. J. Ment. Health Addict. 2022, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ludin, S.M.; Rohaizat, M.; Arbon, P. The association between social cohesion and community disaster resilience: A cross-sectional study. Health Soc. Care Community 2019, 27, 621–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jewett, R.L.; Mah, S.M.; Howell, N.; Larsen, M.M. Social Cohesion and Community Resilience During COVID-19 and Pandemics: A Rapid Scoping Review to Inform the United Nations Research Roadmap for COVID-19 Recovery. Int. J. Health Serv. 2021, 51, 325–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergstrand, K.; Mayer, B. The Community Helped Me: Community Cohesion and Environmental Concerns in Personal Assessments of Post-Disaster Recovery. Soc. Nat. Resour. 2020, 33, 386–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jayles, B.; Cheong, S.A.; Herrmann, H.J. Interactions between communities improve the resilience of multicultural societies. Phys. A Stat. Mech. Its Appl. 2022, 607, 128164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurnio, H.; Fekete, A.; Naz, F.; Norf, C.; Jüpner, R. Resilience learning and indigenous knowledge of earthquake risk in Indonesia. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2021, 62, 102423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lefebvre, H.; Smith, D.N. The Production of Space; Smith, D.N., Translator; Blackwell Publishing: Oxford, MI, USA; Cambridge, UK, 1992; p. 464. [Google Scholar]

- Gottdiener, M.; Hutchison, R. The New Urban Sociology, 2nd ed.; McGraw Hill: Boston, MA, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Sommer, R.; Sommer, B. A Practical Guide to Behavioral Research: Tools and Techniques; Oxford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Sugiyono. Metode Penelitian Kuantitatif, Kualitatif dan R&D; PT Alfabet: Bandung, Indonesia, 2016; p. 334. [Google Scholar]

- Sari, E.S. Audience Research: Introduction to Research Studies of Readers, Listeners and Viewers. In Indonesian: Pengantar Studi Penelitian Terhadap Pembaca, Pendengar dan Pemirsa; Andi Offset: Yogyakarta, Indonesia, 1993; p. 60. [Google Scholar]

- Deng, Y.; Gan, D.; Tang, N.; Cai, Z.; Li, X.; Chen, S.; Li, X. Research on Outdoor Thermal Comfort and Activities in Residential Areas in Subtropical China. Atmosphere 2022, 13, 1357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ANSI/ASHRAE Standard 55-2004 Supersedes ANSI/ASHRAE Standard 55-1992; Thermal Environment Conditions for Human Occupancy. ANSI: Atlanta, GA, USA, 2004; p. 27ISSN 1041-2336. Available online: https://www.ashrae.org/file%20library/technical%20resources/standards%20and%20guidelines/standards%20addenda/55_2017_d_20200731.pdf (accessed on 12 August 2021).

- Xie, X.; Liao, H.; Wang, R.; Gou, Z. Thermal Comfort in the Overhead Public Space in Hot and Humid Climates: A Study in Shenzhen. Buildings 2022, 12, 1454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jakovljevic, M. Empathy, Sense of Coherence and Resilience: Bridging Personal, Public and Global Mental Health and Conceptual Synthesis. Psychiatr. Danub. 2018, 30, 380–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brown, N. (Ed.) Edward T. Hall, Proxemic Theory, 1966; UC Santa Barbara CSISS Classics; California Digital Library University of California: California, CA, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Hall, E.T. The Hidden Dimension; Doubleday: Garden City, NY, USA, 1966; p. 201. [Google Scholar]

- Lalot, F.; Abrams, D.; Broadwood, J.; Hayon, K.D.; Platts-Dunn, I. The social cohesion investment: Communities that invested in integration programmes are showing greater social cohesion in the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Community Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2022, 32, 536–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Macias, T.; Williams, K. Know Your Neighbors, Save the Planet Social Capital and the Widening Wedge of Pro-Environmental Outcomes. Environ. Behav. 2014, 48, 391–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Wang, Y.; Liu, Z. How Does Social Interaction Affect Pro-Environmental Behaviors in China? The Mediation Role of Conformity. Front. Environ. Sci. 2021, 9, 690361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisher, A.T.; Sonn, C.C.; Bishop, B.J. (Eds.) Psychological Sense of Community: Research, Applications, and Implications, 2002nd ed.; Part of the Book Series: The Springer Series in Social Clinical Psychology (SSSC); Kluwer Academic/Plenum Publishers: New York, NY, USA, 2002; p. 354. [Google Scholar]

- Jennings, V.; Bamkole, O. The Relationship between Social Cohesion and Urban Green Space: An Avenue for Health Promotion. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SNI (Indonesia National Standard) 03-6572-2001; Procedures for Design of Ventilation and Air Conditioning Systems. Universitas Negeri Yogyakarta: Yogyakarta, Indonesia, 2001. Available online: http://staffnew.uny.ac.id/upload/132100514/pendidikan/perencanaan-pendingin.pdf (accessed on 12 August 2021).

- Lorenc, T.; Petticrew, M.; Whitehead, M.; Neary, D.; Clayton, S.; Wright, K.; Thomson, H.; Cummins, S.; Sowden, A.; Renton, A. Fear of crime and the environment: Systematic review of UK qualitative evidence. BMC Public Health 2013, 13, 496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, B.; Altman, I.; Werner, C.M. Place Attachment. In International Encyclopedia of Housing and Home; Elsevier Ltd.: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2012; pp. 183–188. [Google Scholar]

- Ross, C.E.; Jang, S.J. Neighborhood disorder, fear and mistrust: The buffering role of social ties with neighbors. J. Community Psychol. 2000, 28, 401–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Francis, J.; Giles-Corti, B.; Wood, L.J.; Knuiman, M. Creating Sense of Community: The Role of Public Space. J. Environ. Psychol. 2012, 32, 401–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peterborough City Council-Cambridgeshire County Council. Strong Families, Strong Communities SECURING Best Outcomes for Children and Young People. Cambridgeshire and Peterborough Early Help Strategy; Peterborough: Cambridgeshire, UK, 2021; 16 pages. Available online: https://www.safeguardingcambspeterborough.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/Early-help-strategy-final-version-12.05.21.pdf (accessed on 12 August 2021).

- The University of Delaware. Building Strong Family Relationships; The University of Delaware: Newark, DE, USA; Available online: https://www.udel.edu/academics/colleges/canr/cooperative-extension/fact-sheets/building-strong-family-relationships/ (accessed on 12 August 2021).

- Kapur, R. Family and Society. 2018. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/323733863_Family_and_Society (accessed on 12 November 2022).

- Akhmedov, B.T. The Family as the Basic Unit of Society. Int. J. Multicult. Multireligious Underst. 2021, 8, 201–204. [Google Scholar]

- Rivera, F.I.; Guarnaccia, P.J.; Mulvaney-Day, N.; Lin, J.Y.; Torres, M.; Alegria, M. Family Cohesion and its Relationship to Psychological Distress among Latino Groups. Hisp. J. Behav. Sci. 2008, 30, 357–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farrell, G. Security through Social Cohesion: Proposals for a New Socio-Economic Governance. Trends in Social Cohesion, No. 628 10; Council of Europenp Publishing: Strasbourg Cedex, Germany, 2004; p. 137. [Google Scholar]

- Asmal, I.; Syarif, E.; Ahmad, M. Harmonization of domestic and social life of fishermen women; a positive behavior for quality of life. Enferm. Clin. 2020, 30, 518–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, S.; Yu, B.; Luo, S.; Zhuo, R. Spatial pattern of the effects of human activities on the land surface of China and the spatial relationship with the natural environment. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2022, 24, 10379–10401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breedvelt, J.J.; Tiemeier, H.; Sharples, E.; Galea, S.; Niedzwiedz, C.; Elliott, I.; Bockting, C.L. The effects of neighbourhood social cohesion on preventing depression and anxiety 636 among adolescents and young adults: Rapid review. BJPsych Open 2022, 8, e97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delhey, J. Social Cohesion and Its Correlates: A Comparison of Western and Asian Societies. Comp. Sociol. 2018, 17, 426–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawachi, I.; Berkman, L. Social cohesion, social capital, and health. In Social Epidemiology; Berkman, L., Kawachi, I., Eds.; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2000; pp. 174–190. [Google Scholar]

- Kingsbury, M.; Clayborne, Z.; Colman, I.; Kirkbride, J.B. The protective effect of neighborhood social cohesion on adolescent mental health following stressful life events. Psychol Med. 2020, 50, 1292–1299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burchi, F.; Loewe, M.; Malerba, D.; Leininger, J. Disentangling the Relationship Between Social Protection and Social Cohesion: Introduction to the Special Issue. Eur. J. Dev. Res. 2022, 34, 1195–1215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scannell, L.; Gifford, R. Defining place attachment: A tripartite organizing framework. J. Environ. Psychol. 2010, 30, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernandez, B.; Martin, A.M.; Ruiz, C.; del Carmen Hidalgo, M. The role of place identity and place attachment in breaking environmental protection laws. J. Environ. Psychol. 2010, 30, 281–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Data Collection | Stakeholder | Sample Collection Technique | Research Question by Questionnaires |

|---|---|---|---|

| Structural | Local people who use spaces | Accidental sample collection | Who is the user of the communal space? (gender and age) |

| How long is the FCS used each day? | |||

| What kind of activity takes place in the FCS? | |||

| Why is the FCS used? |

| Gender | Age | Time Duration | Activities | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Pearson Correlation | 1 | 0.056 | 0.080 | −0.375 ** |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | 0.519 | 0.356 | 0.000 | ||

| N | 137 | 137 | 137 | 137 | |

| Age | Pearson Correlation | 0.056 | 1 | −0.155 | 0.146 |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | 0.519 | 0.071 | 0.089 | ||

| N | 137 | 137 | 137 | 137 | |

| Duration time | Pearson Correlation | 0.080 | −0.155 | 1 | −0.275 ** |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | 0.356 | 0.071 | 0.001 | ||

| N | 137 | 137 | 137 | 137 | |

| Activities | Pearson Correlation | −0.375 ** | 0.146 | −0.275 ** | 1 |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | 0.000 | 0.089 | 0.001 | ||

| N | 137 | 137 | 137 | 137 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Asmal, I.; Latief, R. The Presence of a Family Communal Space as a Form of Local Wisdom towards Community Cohesion and Resilience in Coastal Settlements. Sustainability 2023, 15, 8167. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15108167

Asmal I, Latief R. The Presence of a Family Communal Space as a Form of Local Wisdom towards Community Cohesion and Resilience in Coastal Settlements. Sustainability. 2023; 15(10):8167. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15108167

Chicago/Turabian StyleAsmal, Idawarni, and Rudi Latief. 2023. "The Presence of a Family Communal Space as a Form of Local Wisdom towards Community Cohesion and Resilience in Coastal Settlements" Sustainability 15, no. 10: 8167. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15108167

APA StyleAsmal, I., & Latief, R. (2023). The Presence of a Family Communal Space as a Form of Local Wisdom towards Community Cohesion and Resilience in Coastal Settlements. Sustainability, 15(10), 8167. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15108167