Abstract

The aim of this paper was to investigate the level of necessity for one of the three conditions (organisational capabilities), i.e., exploitation, exploration, and organisational ambidexterity to achieve the desired level of business performance in digital servitisation of manufacturing enterprises. Servitisation (at present, also in combination with Industry 4.0 solutions) is perceived as an important factor for the competitiveness of manufacturers. The idea of (digital) servitisation can also be considered in terms of sustainability. The main expectation here is that successful servitisation will result in a lower environmental impact by moving away from the traditional business model, in which the manufacturer produces the products and then transfers the responsibility for their ownership and use to the customer, towards achieving benefits from the customers’ use of the products (the product remains the property of the manufacturer). Achieving success in digital servitisation requires, among other things, appropriate use of dynamic capabilities, such as exploitation, exploration, or their combination, i.e., organisational ambidexterity. However, it is still unclear to what extent an ambidextrous organisation engages in both types of activities to increase the combined level of exploration or exploitation and how this affects company performance in digital servitisation. On the basis of a survey of a sample of 167 manufacturers, the necessary conditions for achieving the desired performance values were determined. For this purpose, one non-parametric method was used, i.e., necessary condition analysis (NCA). The results show that ambidexterity is not, in every case, a necessary condition for achieving better performance in digital servitisation. Organisational ambidextrousness is a necessary (but not sufficient) condition for better performance in dimensions such as market share, customer retention, sales growth, and overall firm performance. For competitive position, the limiting factor is exploration only, whereas for customer satisfaction, it is exploitation.

1. Introduction

In the last decade, companies have been experiencing two phenomena that are radically changing the way they interact with their customers and how products are developed, manufactured, and delivered [1,2,3]. These phenomena are servitisation and the Industry 4.0 initiative, which, at the same time, pose particular challenges for manufacturing companies. The former consists of a change of orientation from product to service, i.e., in the transformation of product-oriented companies towards offering value in the form of integrated product–service solutions [3]. Industry 4.0, on the other hand, is a new scenario of business development in which the convergence of many different innovative technologies (primarily digital), enhanced by the Internet of Things (IoT), results in cyber–physical and intelligent systems that are capable of creating more value for customers, as well as for the manufacturers themselves.

Although servitisation and digital developments are studied within different sciences and disciplines (the former in management and the latter in engineering and computer science), there is a strong link between them [4]. Progress in servitisation is closely related to the available technologies. Innovative technologies influence the adopted servitisation strategy, the implemented processes, or the shape of the organizational structure of manufacturing companies on the servitisation path [5,6]. The results of recent research indicate that the implementation of digital technologies can significantly accelerate the servitisation process by acquiring the ability to expand the product offering with advanced and innovative product and service solutions [7]. The new technologies that make up the pillars of Industry 4.0 can not only influence the pace of expanding product offerings with services but also completely change the features or forms of service provision [8].

Digital technologies create conditions for the creation of new business models oriented towards services. Their development and delivery to customers requires manufacturing companies to adopt a service orientation at the level of the entire organisation and supply chain [8]. Dematerialisation of physical products changes a company’s place in the supply chain due to closer relationships with end customers resulting from changing forms of engagement with them when providing digital solutions. The competitive position in the supply chain is also changing due to the opportunities to reduce transport and production costs resulting from the dematerialisation of product offerings. Dematerialisation as a consequence of servitisation is also a way to achieve environmentally sustainable firms and customers. The idea of the benefits of sustainability has been reinforced by a surge in environmental awareness, driven partly by the consolidation of organisations whose main aim is to promote the principles of sustainability among governments, companies, and societies [9].

Digital servitisation has implications for the relational power a firm holds in the supply chain and can empower both downstream and upstream firms in the supply chain [4]. Providing product–service solutions, allows manufacturers to create value throughout the product lifecycle and capture it not only from the company’s current position in the supply chain but also along the entire value chain, generating new revenue streams. From this perspective, business servitisation can be seen as a strategic alternative that generates better results [4].

Service orientation, servitisation, and infusion of digital technologies in manufacturing companies have been an area of partly independent research. The combined knowledge of these phenomena has emerged among researchers as digital servitisation, e.g., in [10,11]. Digital servitisation research highlights knowledge gaps in understanding the digital servitisation phenomenon and the impact of factors on its success [7,12].

Firstly, the shift towards digitalisation, smart products, the Internet of Things (IoT), and the Industrial Internet have changed the organisational capability needs of manufacturing firms [13]. Meanwhile, there is little in the literature about strategic dynamic capabilities such as exploitation, exploration, or organisational ambidexterity capabilities that drive companies towards digital servitisation [13]. Exploitation refers to the search for efficiency by improving current product and service offerings and processes in order to streamline them and maximise short-term performance [14,15,16]. This applies to companies using digital technology to improve efficiency in processes, such as production, sales, and delivery [2,5].

However, (digital) servitisation is a risky business strategy in which the benefits become apparent only in the long run, if at all [15]. Hence, exploration capabilities should also be developed. Exploration involves experimenting with radical ideas for new products, services, and disruptive technologies [16], while keeping in mind that the returns from exploration are less certain and more distant in time [14].

Providing digital service–product solutions requires not only exploratory and exploitative capabilities, but a combination of them in the form of ambidextrousness [17]. Companies that have ambidextrous capabilities are able to balance exploratory and exploitative capabilities in such a way that it positively benefits the performance of these companies [17].

However, as researchers point out, e.g., ref. [18], it is not clear to what extent an ambidextrous organisation engages in both forms of activity to increase the combined level of exploration or exploitation. In turn, Kharlamov et al. [12] add that given the phenomenon of the “service paradox” [19,20], it is necessary to study the impact of digital servitisation on firm performance.

Based on this, the aim of the research was to identify the necessity of a minimum level of exploration, exploitation, and organisational ambidexterity capabilities to achieve the desired business performance by companies adopting a digital servitisation strategy.

In order to answer the question posed, research was conducted on a group of 167 Polish manufacturing enterprises of the SME sector. In order to find out the conditions (here, the need for exploitation, exploration, and ambidextrous capabilities) necessary for manufacturing companies to achieve a given level of performance from digital servitisation, the necessary condition analysis (NCA) method was applied.

The paper is structured as follows: First, the concept of digital servitisation, the role of exploitation, exploration, and ambidexterity capabilities in the servitisation process, and measures of its success are discussed (Section 2). Then, the characteristics of the research sample is presented (Section 3). Section 4 presents the research method and the study results. Finally, a discussion of the results and conclusions is included, with an indication of their limitations and future research directions (Section 5).

2. Theory

2.1. Digital Servitisation

Currently, manufacturing companies are facing many transformations that radically change the concepts of building a competitive advantage, relations with customers and suppliers, or ways of developing, producing, and delivering product offerings [15]. Special challenges faced by manufacturing companies are currently seen in two observed macro-trends, i.e., the phenomenon of servitisation and the Industry 4.0 initiative [2].

Servitisation is a phenomenon (process) observed at the level of national economies and at the level of companies themselves, whose product offerings are increasingly expanding to include a service component [20]. Other authors define the servitisation phenomenon as an innovative way of organizing capabilities and processes to better create shared (customer and supplier) value by moving from selling products towards providing integrated solutions composed of products, services, and knowledge [3] Such a transformation is rooted in the value architecture of the solutions offered to customers, composed of forms of value creation, delivery, capture, and their complementarity [21].

As a result, the company develops and offers product–service solutions (PSS) to its customers. There is no consensus in the literature on defining what is a PSS [3]. This paper assumes that a PSS is a personalised offer that responds to the (complex) needs of service recipients (customers), which is designed and delivered interactively with the service recipient and whose components offer synergistic added value by combining products and/or services so that its offered value is more than the sum of the offered value of its individual components. PSSs integrate components, such as product, service, and knowledge, into unique combinations in order to fulfil customer requirements and needs. In extreme cases, the expenses incurred by the provider are compensated by the recipient of the service on the basis of value in use [22].

Industry 4.0, on the other hand, is considered a new industrial scenario in which there is a convergence of various new technologies supported by the Internet of Things (IoT) [5,23,24]. For a long time, these issues were treated as separate research areas, with the former focusing on customer value and the latter on the value of internal business processes [15]. In fact, both trends are closely related, and their common ground is digital technologies on which, in turn, smart products, digital services, mass personalisation of product offerings, or other innovative value proposition models are based, e.g., [15]. The technologies and solutions that make up Industry 4.0, such as IoT, big data, cloud computing, analytics, or cyber security, are now becoming the basis for increasingly complex and integrated digital product and service offerings [23].

Digital servitisation is seen as the use of digital technologies to develop and exploit value from product and service offerings. Digitalization essentially means the transition from analogue to digital technology [5]. More specifically, it is a technical process that transforms analogue information into a digital form that can be processed by the same technologies [24]. Digitalization offers a number of opportunities for companies [15]. It enables scalability in the efficient creation and delivery of products and services [2,5] and extends the reach of firms through new digital channels, such as websites and mobile devices [8]. Moreover, digitalization has the potential to radically change a company’s entire business model [25] and ultimately change its position in the supply chain [4] and value chain [5,13]. It is important to note that digitalization does not always trigger disruptive change—more often than not, companies use digital technologies to incrementally improve their current value proposition [26].

2.2. A Dynamic Capabilities in Digital Servitisation

The servitisation literature often emphasises the importance of service-related capability development for servitisation success [20], as well as digital servitisation [13,27], which highlight the role of sensing, seizing, and reconfiguring capabilities as essential for service development, such as continual monitoring of competitors’ service offerings, the ability to make quick and timely decisions, and redesigning processes to minimise costs and make profits. In addition, to benefit from digital servitisation, companies also need capabilities related to data analytics (combining and analysing data) [13], which help them to better interact with customers and co-create value [28].

While the benefits of these operational capabilities are obvious, there is little in the literature about strategic capabilities, such as dynamic capabilities, that drive companies towards digital servitisation [13]. Dynamic capabilities make firms continually adjust their strategy according to the ongoing changes in the environment in which they operate [21]. Exploring the role of dynamic capabilities in digital servitisation is important because they are considered a resource for firms to create a sustainable competitive advantage [15]. In particular, exploitation, exploration, and ambidexterity are found to be important capabilities driving technological and product–service innovation strategies [17].

Exploitation refers to the use of existing knowledge to improve the products and services or business processes offered to improve performance, while exploration is the creation of new knowledge to develop new (breakthrough) products and services [14,16]. Ambidexterity is the ability of an organisation to maintain an appropriate relationship between exploitation and exploration capabilities [29]. As a result, the ability of companies to adapt to the continuous and often rapid changes in the business environment increases.

Exploitation is the seeking of efficiency by improving current product and product-service offerings and processes in order to streamline them and maximize short-term performance [14,16]. This refers to firms using technology to improve efficiency in processes, such as production, sales, and delivery [2,17]. Some authors note that exploitation is not a characteristic of companies on the servitisation path. Servitisation is a risky business strategy in which the benefits become apparent only in the long term, if at all [19]. In fact, firms with an exploitative orientation are less likely to compete through innovative products and services [30].

Exploration, on the other hand, involves research and development with breakthrough ideas for new products and services [13]. Thus, the expected benefits of exploration are less certain and extended over a longer period of time [14]. Today, companies with an exploration orientation are increasingly adopting new technologies from the so-called “Industry 4.0” technology area [2,5]. They aim not only to integrate and further automate companies’ business processes [2] but also to lead to omnipresent interoperability among products, machines, and people [31]. Companies with an exploration orientation are also associated with the development of new product offerings [30] and the development of new service business opportunities [27]. Exploration capabilities are considered crucial for the development of advanced services, as opposed to exploitation, which is more related to basic services [32].

As can be seen, both types of capabilities described above can be crucial for a company. The ability of a firm to employ a strategy of exploration (seeking new opportunities) and exploitation (using existing competencies) at the same time is known in the literature as ambidexterity [29]. As noted, these two types of abilities are interrelated [29]. Hence, the phenomenon of seeking to simultaneously maintain both types of organisational capabilities is investigated. The concept of ambidexterity is seen as one of the key capabilities for achieving sustainable competitive advantage for organisations and is gaining prominence in the academic literature and research that is conducted [29]. Ambidexterity is studied in the literature within various disciplines, e.g., strategic management, marketing literature, or organisation theory [29,33]. Researchers agree on the definition of ambidexterity as the simultaneous pursuit of exploration and exploitation. Tushman et al. [29] define ambidexterity as “the ability to implement both incremental (i.e., exploitative) and revolutionary (i.e., exploratory) change”. March [14] emphasizes that when a firm focuses too much on existing competencies and develops them more strongly compared with exploration, it may have organizational myopia or organizational inertia. The strategic logic to solve this problem is ambidexterity [34].

Despite the research efforts already made in the area of exploration, exploitation, and performance, important questions remain. For example, it is not clear to what extent an ambidextrous organisation engages in both forms of activity to increase the combined volume of exploration or exploitation. In their review of exploration and exploitation, [35] (p. 137) conclude that ‘the evidence to support the performance implications of exploration and exploitation is relatively limited’. Similarly, Raisch, and Birkinshaw [36] (p. 393), in their review of the literature on ambidexterity, conclude that “In sum, the empirical evidence on the relationship between performance and ambidexterity is limited and inconclusive”. Overall, this suggests that despite the impact and importance of exploration, exploitation, and, ultimately, ambidexterity, the evidence is limited as to whether these capabilities matter, or to what extent they matter, for the success of digital servitisation.

Therefore, this paper attempts to examine the level of necessity of one of the three conditions (organisational capabilities), i.e., exploitation, exploration, and organisational ambidexterity to achieve the desired level of business performance in digital servitisation of manufacturing enterprises.

2.3. Success Measures of Servitisation

The success of servitisation is seen as a way to achieve differential advantage by providing services and solutions instead of just selling products [37]. In doing so, a number of strategic and economic benefits are expected for manufacturers. One of these is increased customer loyalty. Services require manufacturing companies to increase their customer focus, which translates into a stronger relationship between the customer and the digital solution provider. On the economic side, manufacturers expect services to improve profitability, provide stable revenue streams, and, thus, enable business growth.

Hence, success in servitisation is multidimensional—achieving competitive advantage, financial result (profitability, profit), and customer loyalty. It is often stated that financial measures are insufficient and the measurement should include both financial and non-financial criteria while distinguishing two levels of success measurement: the service level and the enterprise level. Ulaga and Reinartz [37] define the success of service orientation as achieving the set business goals by differentiating one’s product offering by including services, thus achieving a competitive advantage. Raddats et al. [20] add financial performance and customer loyalty to this. With regard to financial measures at the service level, producers can measure service profitability and service revenue. At the company level, the measures used are the overall profitability of the company or a comparison of financial performance against competitors [37].

With respect to non-financial measures, at the service level, it is the customers who can be the source for assessing the quality of service provided by the provider. Grönroos and P. Helle [38] point to a proposal for a measure of success shared by the producer and the customer. According to the authors, productivity growth of the supplier and its customer is a good measure of value co-creation. An increase in customer satisfaction is also proposed as a non-financial measure of the success of service orientation at the company level, which, in turn, can lead to customer loyalty and retention. It should be noted that each of the measures mentioned is not without its drawbacks (more can be found in, e.g., [20]).

The literature provides abundant evidence of the strategic and financial benefits achieved from servitisation [20] in trying to identify and explain the impact of different organisational elements on the success from its adoption. However, practice shows that many companies entering the path of increasing the share of services in their product offerings face many difficulties that may lead to the phenomenon of deservitisation [39], or the so-called service paradox, where despite the increase in the share of services, companies do not achieve the intended benefits [19]. The author notes that there are companies in which, even when their revenues increase, often generate less profit compared with manufacturing companies that do not do so. The identification of such problems has become a challenge first for researchers of the servitisation phenomenon [39] and now digital servitisation. As highlighted, the problem of research on the impact of servitisation on business performance is still at a very early stage [13].

3. Research Method

3.1. NCA Method

In order to determine the conditions (here, the need for exploitation, exploration, and ambidextrous capabilities) necessary for manufacturing companies to achieve a given level of performance from digital servitisation, the NCA method was applied [40]. The method belongs to the group of non-parametric methods which use a linear programming procedure, but the influence of the random factor on the features of the objects is not taken into account. The advantage of NCA resulting from the non-parametric nature of the method is that it does not require the presentation of a functional relationship between/among the analysed variables. The NCA helps researchers determine the level of condition necessary (but not sufficient) to achieve the desired level of effect (outcome). In that case, it allows one to answer, among others, the question of the type “what minimum level of the value of the independent variable X is necessary for a given level of the value of the dependent variable Y (understood as the desired result, effect)?” In order to identify the necessary value of a given variable for the desired effect to occur, in the NCA method, the so-called ceiling line must be determined. In the Cartesian coordinate system, the ceiling line is the boundary line separating the zone without registered observations (points) from the zone in which these observations are located. The ceiling line takes the form of a non-decreasing (linear) function with intervals [40]. There are many ways to determine such a line. The NCA adapted, inter alia, solutions from the previously developed method of boundary data analysis (data envelopment analysis—DEA) and free envelope determination methods (free disposal hull—FDH) [40]. The “empty” zone (usually above the ceiling line) is proof of the existence of a necessary condition. It will vary in size, thus determining the measure of the necessity effect (d) but not the sufficiency condition. In NCA, the magnitude of the precondition effect is expressed as the size of the zone above the ceiling line (“empty” zone) to the entire area of recorded observations [40]. The effect is stronger as the zone above the ceiling line increases. As with other measures of effect size, such as the correlation coefficient r, in NCA, the value of the necessary condition effect ranges from 0 to 1 [40].

NCA also allows for multivariate analysis. The traditional approach uses correlation or regression. In this situation, the correlation or regression coefficient enables the determinant variables to be found. However, with this approach, the variables can compensate for each other. In NCA logic, each single necessary determinant Xi must always have its minimum level Xic to allow Yc to be achieved, regardless of the values of the other determinants. If Xi falls below Xic, the other determinants cannot compensate for it. After a fall, the desired outcome Yc can only be achieved again if Xi rises to Xic. Thus, the identification of the preconditions as the introduction of the minimum required levels and the maintenance of these levels, i.e., the fulfilment of the preconditions, forms the basis for the achievement of the goal [41] (p. 6).

3.2. Measures

The constructs used in the study were generated using the positions of the scales already used in previous studies.

3.2.1. Digital Servitisation

The measurement of digital servitisation was based on the proposal made by Coreynen et.al. [15]. Digital servitisation is measured by two variables, digitisation (DIG) and servitisation (SERV). Respondents were asked whether their company had developed a strategy for each of these two areas. A five-point Likert scale was used for this (from 1 = ‘strongly disagree’ to 5 = ‘strongly agree’). The digitisation dimension was taken as the transition of companies from analogue to digital technology [42], encompassing all the tools and processes needed to perform various activities and create value for customers in the form of creating and delivering product and service solutions. Following Vandermerwe and Council [1], the term servitisation has been adopted as a transition from the development and sale of goods or services in their pure form towards an integrated product and service offering. As the term servitisation may not have been familiar to all respondents, the phrase product–service integration was also used, which, as in the literature, is used interchangeably with the term servitisation [15]. The results of the responses to the DIG and SERV questions were then multiplied. Thus, the result could range from 1 (no DIG and SERV strategy) to 25 (the company has developed a strategy for both DIG and SERV). Next, those cases were extracted for which the answers to the DIG and SERV questions were simultaneously scored no lower than level 3. This ultimately reduced the analysed set of firms from 320 to 167, for which the product (DIG*SERV) ranged from 9 to 25.

3.2.2. Firm Performance

The selection of firm performance variables followed Morgan et al. [43] through single-scale items related to: (1) finance (sales growth of product and service solutions), (2) market (market share, customer satisfaction, competitive position, and customer retention), and (3) ‘overall firm performance’.

Due to limitations related to data availability and the ability to generate objective performance ratings, perceptual performance ratings were used. Research indicates the validity of this approach, as a high correlation has been found between objective and perceptual indicators [44].

Since the items are relative in nature, they should be clarified accordingly. The main direct competitors of the surveyed firms were considered as a reference [45]. For the purpose of measuring business performance, respondents were thus asked: “With reference to the main market in which your firm operates, how would you rate your firm’s performance over the past year compared to your main direct competitors in terms of…” in the items listed. Responses were rated on a scale from 1 (much worse) to 5 (much better).

3.2.3. Exploitation, Exploration, and Ambidextrousness

In line with previous studies (e.g., [43]), separate scales were adopted for exploration and exploitation, and ambidexterity was taken as the ability of firms to consistently perform both dimensions simultaneously [46]. Following Gupta et al. [47], it is assumed that exploration and exploitation are not necessarily opposed to each other. In modelling organisational ambidexterity, some studies have considered exploration and exploitation as poles on a continuum and ambidexterity as the optimal point on this continuum (e.g., [48]). Others have considered exploration and exploitation as independent activities and ambidexterity as a combination of both (e.g., [49]). Furthermore, Cao et al. [50] indicated that separating the construct of ambidexterity into separate dimensions may explain previously unaccounted for variance in firm performance. In this study, although exploration and exploitation are considered as separate dimensions and ambidexterity as a firm’s ability to consistently perform both dimensions simultaneously [49], the inherent trade-offs between them are not ignored, nor are they seen as complementary [48]. It is accepted here that exploration and exploitation are not necessarily in opposition [47].

Hence, organisational ambidexterity was modelled using multivariate necessary conditions analysis, reflecting the argument that these two organisational capabilities are non-substitutable. Ambidexterity was modelled as a representation of the need for two determinants (here exploitation and exploration) to occur at a particular level. This is in the nature of a multivariate analysis, in which cases are examined where more than one determinant contributes to a given level of outcome.

Finally, the selected measures were adapted from studies by Coreynen et al. [15] and Dhir et al. [18]. Exploratory measures describe a company that, among other things, “introduces a new generation of products and services” and “enters new technological areas”. Exploitation capability, on the other hand, is expressed through the company’s efforts to ‘reduce total costs’ and ‘improve current processes’. Using a scale of 1 (much worse) to 5 (much better), respondents rated the orientation adopted by their company compared with their main competitors over the past five years.

3.3. Research Sample and Data Collection Method

The surveyed entities were production companies based in Poland, which declared to have services in their product offer, and employed at least 10 employees. The research sample was selected purposively on the basis of the Central Statistical Office data from the REGON register, 2017. Moreover, the selection of enterprises was based on a quota, in an effort to comply with the data of the Central Statistical Office in such dimensions as the percentage share of enterprises from a given section and division of the Polish Classification of Activities and according to the employment structure. To collect the data, the CATI method of direct interview (computer-assisted telephone interview) was used. The interviews were conducted by one of the largest companies in Poland conducting this type of research. The research sample consisted of 320 companies, but due to the separation from this group of companies that have a digital servitisation strategy in place (see Section 3.2), ultimately, 167 companies were included in the research. The respondents were employees of higher and middle management level, i.e., owners, managing directors, sales and marketing directors, service department managers, and new product development managers. The respondents represented companies from seven different industries: production of machinery and equipment (41%), production of electrical equipment (16%), activities related to software and IT consultancy and related activities (13%), production of motor vehicles, trailers, and semi-trailers (10%), manufacture of other transport equipment (9%), manufacture of computers (8%), and telecommunications (3%). The surveyed companies employed: 10–49 employees (51%), 50–249 employees (40%), and 250 employees and more (9%) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Sample characteristics.

4. Method and Results

The research involved determining the level of necessity of the determinants (here, exploration, exploitation, and ambidexterity capabilities) to achieve a certain outcome (here, the results achieved by companies adopting a digital servitisation strategy). Without the presence of a necessary condition at the required level, the desired results cannot be achieved. Moreover, they cannot be replaced by other outcome determinants (even with better values). As a first step, the validity and reliability of the measurement tool was verified for the variables exploration and exploitation (the other variables were assumed to be unidimensional constructs). For this purpose, descriptive statistics (Table 2) and exploratory factor analysis (EFA) were used (Table 3), and Cronbach’s alpha was calculated (Table 2).

Table 2.

Means, standard deviations, correlations, and Cronbach’s alpha values.

Table 3.

Factor analysis results for the exploration and exploitation items.

Exploratory factor analysis (EFA) allows the use of a statistical method to eliminate inappropriate items, thus increasing the reliability of the scale. As indicated by [51], EFA can be carried out early in the development of a new measurement scale as well as when modifying the measurement tool (the latter is the case in this study).

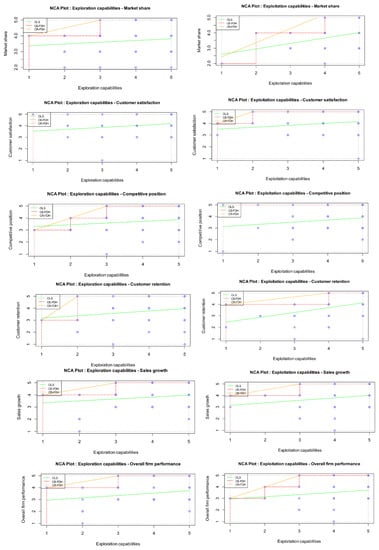

As mentioned above, this research considers exploration and exploitation as separate dimensions, and ambidexterity as the ability of the firm to consistently perform both dimensions simultaneously. Therefore, we first examined what minimum level of a given determinant factor X is necessary for what level of outcome Y. That is, what is the level of necessity for the occurrence of exploration and exploitation abilities (separately for each of these capabilities) to achieve digital servitisation results in the assumed six dimensions, i.e., market share, customer satisfaction, competitive position, customer retention, sales growth, and overall firm performance. For this purpose, the effect sizes of the necessary conditions d were determined (Table 4) by drawing the CE-FDH ceiling line (Figure 1).

Table 4.

The results of the analysis of the necessary conditions: values of the effects d(CE_FDH).

Figure 1.

Ceiling (limit) lines for the necessary conditions.

In order to analyse the impact of organisational ambidexterity on performance—taking exploration and exploitation as separate dimensions and ambidexterity as the company’s ability to consistently pursue both dimensions simultaneously—another tool from the NCA method was used, i.e., the multivariate bottleneck technique. On the basis of a table of constraints (Table 5), the necessary (but not sufficient) minimum levels of exploration and exploitation capability for different desired performance levels were examined.

Table 5.

Table of constraints: the multivariate necessary condition with two necessary conditions (capabilities).

4.1. Measures

4.1.1. Descriptive Statistics

In the first step of the EFA analysis, descriptive statistics of the survey items were presented, i.e., mean (M) and standard deviations (SD). This was to check the adequacy of the measurement and to detect survey items for which the mean values were close to the extremes (1 and 5). If these appeared, consideration should be given to eliminating them from further analysis [52].

Table 2 shows the descriptive statistics, including the means, standard deviations, and correlations of the nine measurement instrument variables (six one-item digital servitisation performance scales, i.e., market share, customer satisfaction, competitive position, customer retention, sales growth, and overall firm performance, as well as a three-item exploration capabilities scale and two-item exploitation capabilities scale). The highest correlations are between exploitation and exploration (r = 0.68, p < 0.05). It confirms that both constructs are complements rather than substitutes [15].

4.1.2. Statistical Evidence of Validity with Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA)

In order to detect a pattern of structure for two factors (i.e., exploitative and exploratory capabilities), the respondents’ given answers to nine statements from the authors’ measurement scales [15,18] were taken into account. (Table 3) Factors were extracted for the number of eigenvalues greater than one. The Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin measure was used to verify the adequacy of the sampling for the analysis [52]. The analysis revealed that the KMO measure = 0.75 (with a threshold of 0.6, according to [52]). The test for the condition of sufficient correlation among items was carried out using Bartlett’s sphericity test. The obtained results, χ2 (36) = 1282.513, p < 0.000, indicate that they are sufficiently large to perform EFA.

As recommended by [52], a threshold of 0.70 was used as the criterion for factor loading in EFA. Five of the nine items conceptually loaded correctly on two factors (Table 3). Exploratory factor analysis confirmed the pattern of two factors. A scale with two items was found to measure exploitation capability, a scale with three items for exploration capability. In total, a five-item scale explained 68.26% of the variance. The percentages explained by each factor were 53.96% ( exploration capability), 14.29% (exploitation capability) respectively.

4.1.3. Analysis of Scale Reliability

In order to determine the reliability of the scale, the Cronbach’s α-coefficient was used, i.e., a measure determining the consistency of items present in a given scale (in other words stating to what extent the questions included in a given factor determine the same theoretical construct). The Cronbach’s α-coefficient at the level of 0.83 and 0.89 (exploration and exploitation, respectively) was achieved with a cut-off value of 0.6 on a 5-point Likert scale [53] (Table 2). The final measurement tool has sufficient reliability to measure.

4.2. Exploration and Exploitation as Separate Dimensions

The results of the necessary effects (d(CE_FDH)) (Table 4) indicate that, in the case of exploration, its occurrence is not a necessary condition for the business outcome in the customer satisfaction category (d(CE_FDH) = 0). In the other five dimensions, the value of d(CE_FDH) is in the range <0.1;0.3>.

On the basis of previous studies [54], effect sizes d(CE_FDH) between 0.1 and 0.3 are already considered significant from a theoretical and practical point of view.

The next step is to check whether the observed empty space is statistically significant and not a random sample. In the case of NCA, the approximate permutation test is used for this [55] as a result of which the p-value is determined. The calculation of the p-value involves formulating a null hypothesis assuming that the observed sample data are random chance and then calculating the probability (p) that the effect size in the observed sample is equal to or greater than the effect size in the random samples. For p < 0.05, it is assumed that the observed sample is unlikely to be the result of a random process [55]. It should be noted that the accuracy of the p-value in the permutation test depends not only on the p-value but also on the number of permutations performed. As the number of permutations increases, the accuracy of the p-value increases.

The significance test carried out showed that for both exploration and exploitation, all effects obtained were found to be significant (i.e., p-value < 0.05) (Table 4) The p-value was calculated with parameters: number of resamples in the statistical approximate permutation test = 10,000; confidence level of the estimated p-value (p accuracy) = 0.95; and the threshold significance level in the returned plot of the statistical test = 0.05.

This means that exploration capabilities are necessary (but not sufficient) conditions for success in digital servitisation in dimensions such as market share, competitive position, customer retention, sales growth, and overall firm performance. Exploration limits competitive position (d(CE_FDH) = 0.188, p = 0.038) and market share (d(CE_FDH) = 0.167, p = 0.002) most strongly. The other dimensions, i.e., customer retention, sales growth, and overall firm performance, are constrained by exploration at the same level, i.e., (d(CE_FDH) = 0.125, at the same level of p = 0.042). According to Dul [40] (p. 271), it is possible to assess the values of these effects at the “medium” level (when the value of d(CE_FDH) is between 0.1 and 0.3, the effect is considered as “medium”, for values above 0.3 to 0.5 it is considered as “large”, and above 0.5 as “very large”).

In the case of exploitation, the result showed that this capability is not a necessary condition for competitive position, while for customer satisfaction, the effect of the necessity of exploitation should be considered insignificant (d(CE_FDH = 0.063, p = 0.004). The strongest constraint is market share (d(CE_FDH) = 0.417, p = 0.034). This is followed by customer retention (p = 0.000) and overall firm performance (p = 0.026) (d(CE_FDH) = 0.188) and sales growth (d(CE_FDH) = 0.125, p = 0.000). In summary, exploitation is a necessary (but not sufficient) condition in four dimensions of business performance, i.e., market share, customer retention, overall firm performance, and sales growth.

4.3. Multivariate Analysis of Necessary Conditions

Thus far, the analysis has been conducted with two variables, i.e., one X (either exploration or exploitation), which is necessary for one Y (one of the six dimensions of business performance). In order to analyse organisational ambidexterity, taking exploration and exploitation as separate dimensions and ambidexterity as the firm’s capability to consistently perform both dimensions simultaneously, it is necessary to consider a more complex situation: more than one necessary condition (exploration and exploitation) and one Y (one of the six dimensions of digital servitisation performance). In necessary-but-not-sufficient logic, each single necessary determinant must always have its minimum level to allow a given level of outcome to be achieved, regardless of the values of the other determinants. If one determinant falls below the minimum level, the other determinants cannot compensate for it. This lack of a compensatory mechanism points to the possibility of using the multivariate bottleneck technique to investigate the necessity of organisational ambidexterity for servitisation success. Different determinants (exploration and exploitation) impose different constraints on performance. Using the bottleneck technique, it was determined which determinants become successively the weakest links (bottlenecks, constraints) if the desired outcome increases. In other words, for a given desired level of performance, multivariate analysis of necessary conditions identifies the necessary (but not sufficient) minimum values of the determinants for the desired outcome to be achievable.

Hence, the bottleneck table (Table 5), shows what minimum level of necessary conditions (exploration, exploitation) is required for different desired performance levels. The values of the six business performance measures are expressed as a percentage of the range of (observed) values (0% = lowest observed value, 100% is the highest observed value, and 50% is in the middle of the lowest and highest observed value). The values in Table 5 indicate that achieving a 10 to 60 market share (10% to 60% of the range of observed values, i.e., from “much worse than our main competitors” to “similar to our main competitors”) is necessary (but not sufficient) to achieve an exploitation level of 25 (25% of the range of observed values). In this case exploration is not a necessary condition. In achieving higher levels of market share, it is already necessary to achieve an exploitation at a level of 75 and exploration at a level of 50. Failure to meet one of these conditions does not allow us to achieve a market share of 70 or more (“better than our main competitors” and “much better than our main competitors”). For customer satisfaction, only exploitation is a constraint, which is a necessary (but not sufficient) condition for achieving a customer satisfaction level of 80 and above (“better than our main competitors” to “much better than our competitors”). Customer retention at level 60 and above is limited by exploration, but from level 80 and above (“better than our main competitors” to “much better than our competitors”), the necessary condition for reaching level 75 by exploitation must additionally be met. Competitive position from level 60 to 70 is limited by exploration (with a value of 25). Achieving a level of competitive position higher than 70 is still only limited by exploration, but with a higher value of 50. Sales growth results from level 80 (“better than our competitors”) are limited by both exploration and exploitation (with the same value (50)). Overall company performance at levels 60 and 70 (“similar to our main competitors”) is limited by exploitation (with a value of 25). However, already achieving an overall firm performance score of 80 and above (“better…” and “much better than our main competitors”) requires achieving a higher value of exploitation (with a value of 50) and exploration (also with a value of 50).

5. Discussion and Conclusions

Achieving the sustainability of organisations and businesses is a priority in today’s world. Finding sources of sustainable competitive advantage is much needed, especially when considering the high uncertainty experienced by companies [9]. In the past, it was widely expected that economic benefits would lead the way in describing a sustainable enterprise. Now, growing environmental concerns, a consequence of long linear economies, have shown that immediate action is needed. One of these is to change the business model adopted by manufacturing companies [9]. Product companies implementing digital technologies are gradually adopting service-based business models. This phenomenon is known in the literature as digital servitisation [1,2,3,4]. Through (digital) servitisation, companies are able to differentiate their offerings and increase customer engagement while leading to reductions in production and transport costs [4]. However, achieving success in digital servitisation requires the appropriate use of dynamic capabilities such as exploitation, exploration, or a combination of the two, i.e., organisational ambidexterity [15]. However, it is still unclear to what extent an ambidextrous organisation engages in both types of activities to increase the combined level of exploration or exploitation and how this affects a company’s performance in digital servitisation [18,19,20].

The present research is part of the trend of exploring the role of dynamic capabilities in digital servitisation. In particular, exploitation, exploration, and ambidexterity are shown to be important capabilities driving technological and product–service innovation strategies [15]. Following [50], organisational ambidexterity was assumed to consist of exploitation and exploration, which are two conceptually different dimensions and characterised by different mechanisms of influence on firm performance.

The aim of the research was to identify the necessity of a minimum level of exploration, exploitation, and organisational ambidexterity capabilities to achieve the desired business performance by companies adopting a digital servitisation strategy. The necessary condition analysis (NCA) method was used to identify the necessary conditions.

Firstly, we examined what is the required minimum level of necessity for the occurrence of exploration and exploitation capabilities (separately for each of these capabilities) to achieve digital servitisation results in the adopted six dimensions, i.e., market share, customer satisfaction, competitive position, customer retention, sales growth, and overall firm performance. The results showed that exploration capabilities are a necessary (but not sufficient) condition to achieve success in digital servitisation in dimensions such as market share, competitive position, customer retention, sales growth, and overall firm performance. The occurrence of exploration capability is not a necessary condition for customer satisfaction performance.

In the case of exploitation, it resulted that this capability is not a necessary condition for competitive position. Exploitation limits market share the most, followed by customer retention, overall firm performance and sales growth. Exploitation limits the customer satisfaction dimension the least.

The results obtained reveal, in contrast to, e.g., [32], that in the case of advanced services (here, digital services), exploratory capabilities are not always considered crucial for their development, in contrast to exploitation, which, according to [32], is more related to basic services. In companies with a digital servitisation strategy, the importance of exploratory or exploitative capabilities depends on the objectives to be achieved. This means that both exploitative and exploratory companies pursue a digital servitisation strategy, albeit in different ways, with different objectives, thus confirming the conjecture made by [15]. Furthermore, the results obtained respond to the calls made by [35,36] for empirical verification confirming the relationship between company performance and exploratory and exploitative capabilities. The present results confirm that such relationships are present (for both exploratory and exploitative capabilities) in such dimensions of servitisation success as market share, customer retention, sales growth, or overall company performance. In the dimensions of customer satisfaction and competitive position, only exploitative or exploratory capabilities, respectively, were found to be a condition for success. This indicates that the relationship between ambidextrousness and these dimensions of digital servitisation success was not confirmed (as verified in the next stage of this research and discussed below).

The second step of the research sought to answer the question of the extent to which the ambidextrous organisation engages in combined levels of exploration and exploitation [18] and what impact this has on the performance of companies with an adopted digital servitisation strategy [12].

The necessity of the co-occurrence condition of exploration and exploitation (i.e., organisational ambidexterity) in achieving the desired levels of six different performance categories in digital servitisation was investigated. For this purpose, the multivariate bottleneck technique was used. The results show that ambidexterity is not, in every case, a necessary condition for achieving better performance in digital servitisation. This clarifies the issues reported by the authors [35], who argue that the relationship between performance and ambidexterity is ambiguous. It turns out that ambidexterity is not, in every case, a prerequisite for digital servitisation success. The results obtained indicate that it depends on the dimension of digital servitisation success. Organisational ambidexterity is a necessary (but not sufficient) condition for achieving better performance in dimensions such as market share, customer retention, sales growth, and overall firm performance. For the two performance measures, the limiting conditions were either exploration (for competitive position) or exploitation (for customer satisfaction).

As in the authors’ study [12], the present findings showed possible trade-offs requiring some balance between exploration and exploitation, depending on the digital servitisation goals set. As March [14] points out, exploration and exploitation compete for scarce resources and require such fundamentally different requirements from the firm that they cannot be reconciled, a trade-off requiring balance. This is visible both in the dimensions that can be classified as measures of organisational growth (market share, sales growth, or overall firm performance), for which the base is exploration [32], and for customer retention, which belongs to the organisational effectiveness group, and for which the base is exploitation [55]. The exceptions are competitive position and customer satisfaction. In the first case, the main factor limiting the achievement of better results is exploitation only; in the second case, it is exploration.

The obtained results show yet another issue. Apart from competitive position, for the remaining analysed performance dimensions (both from the organisational growth and organisational effectiveness group), higher levels of performance are more strongly constrained by exploitation than exploration. This confirms the theory of servitisation path proposed by [56] and once confirmed by quantitative methods by [17]. The research was conducted on a sample of Polish enterprises. Castelo-Branco et al. [57] conducted research on the maturity of the infrastructure that comprises Industry 4.0 and the use of big data analytics in industrial enterprises of European Union countries. Poland, alongside Hungary and Bulgaria, was in the least mature group. As the authors called it, in the “Laggards” group. This means that Polish enterprises are rather at the initial stage of digital servitisation. If so, according to the results of studies [30] which suggest the existence of an optimal pathway for deploying exploitation and exploration capabilities, Polish enterprises first must encompass exploitation, exploration, and the interplay between both—strategic ambidexterity.

The final conclusion of the research concerns necessity inefficiency. It should be noted that the minimum necessity levels of exploitation or exploration are different for different desired levels of a given performance category. The obtained research results indicate that the increase of the desired level of a given performance is limited by an increasing necessary minimum level of capability. However, it should be added that in each of the six performance categories, once a certain level of capability is reached, its further increase does not affect the achievement of a higher level of performance. For example, for the market share category (Table 5), both level 70 and 100 are constrained by the same level (i.e., 75) of exploitation capability. In this case, further increases in the level of exploitation may already be inefficient for the company. This is a necessary but not sufficient condition for higher performance levels to be achieved.

In the context of necessity inefficiency, it should be noted that the above-discussed insights can explain the phenomenon of the service paradox highlighted in the literature and which still needs to be addressed to understand its causes [12,19,20]. Previous research findings on digital servitisation show that many companies embarking on the path of increasing the share of services in their product offering do not ultimately achieve the intended benefits [12,19]. As these research results show, a different combination of exploration and exploitation capabilities is required depending on the performance category. Unnecessary excess of one over the other leads to inefficiency. Any further increase in resources to raise above the maximum necessary level of exploration and exploitation capabilities generates additional costs that will not yield better results.

This study contributes to the current servitisation research field in three ways. First, it answers the call for research on strategic capabilities in digital servitisation [35,36]. In particular, the results show in which cases exploitation, exploration, or ambidexterity capabilities in digital servitisation are necessarily required according to different categories of business performance. Secondly, the results of this research provide new knowledge to explain the phenomenon of the ‘service paradox’, i.e., the situation where despite the increase in the share of services, companies do not achieve the intended benefits [18]. On the basis of the research results obtained, it can be concluded that companies’ experience of the service paradox phenomenon may be the reason for not having the necessary levels of exploration and/or exploitation capability that are required for the different desired levels of performance. Thirdly, as the authors point out (e.g., [11,20]), the current body of research on digital servitisation and the study of service paradox so far consists mainly of qualitative studies that examine servitisation, often in a descriptive manner. The present research findings have enabled us to find empirical support against or in favour of previous assumptions about digital servitisation. These three elements offer important theoretical contributions to the literature that, despite a growing number of publications, is still considered to be in the theoretically nascent stage [3].

The results of the research also address the dilemmas of managers regarding which, and to what extent, dynamic capabilities need to be developed in order to succeed in digital servitisation. The results of the research showed that the necessary level of organisational exploitation, exploration, and ambidextrous capabilities depends on the business performance category. Managers wishing to increase market share through digital servitisation must first and foremost focus on using digital technologies to improve their service and product offering (exploitation) to improve efficiency in processes, such as production, sales, and delivery. However, such an approach will only allow one to get closer to the competition. In order to dominate the market in this dimension, it is necessary to develop simultaneously the ability to explore (i.e., ambidextrousness). This means that companies should devote part of their resources to activities related to the acquisition of new (here, digital) technologies that give the possibility of extending their product range with new types of digital solutions provided. If a high level of customer satisfaction is to be maintained, it is required, above all, to focus their efforts and resources for improving their offerings and continually increasing the efficiency of their business processes. The opposite is true for the need to increase one’s competitive position. Here, the findings of the research clearly showed that, in the case of digital servitisation, a prerequisite for achieving a very good competitive position is the development of exploratory capabilities. These should help to expand the range of digital product and service solutions in order to differentiate oneself from the competition. This will involve the need to acquire or access the latest technologies (cloud computing, Internet of Things, etc.) and new competences (e.g., data analytics). Customer retention, sales growth, as well as overall company performance in the case of digital servitisation, are limited by both exploration and exploitation (ambidextrousness) capabilities. In the case of customer retention, although ambidextrousness is required for above-average performance in this category, it is more strongly constrained by exploitation than exploration. This means that customer retention requires the development of new service offerings, but more emphasis should be placed on excellent delivery of services already offered. Above-average sales growth, on the other hand, can be achieved when companies simultaneously make a similar effort to meet the needs of existing customers or markets and to meet the needs of new customers or open new markets through new (digital) product offerings or the development of new distribution channels. It should be noted, however, that in the case of overall performance companies, although ambidextrousness is required for above-average performance, exploitation capabilities constrain them more strongly at the level of average performance. This means that firms should not just focus the effort more strongly on exploitation than exploration. If there is an imbalance, companies are more likely to experience obsolescence. From exploiting existing technologies and meeting the needs of existing customers, firms tend to benefit in the short term. However, this advantage may not be sustainable due to changing environments, technologies, and market conditions. Therefore, overall company performance may suffer in the long term as a result of not having the required level of development of exploration capabilities.

This research, like others, has its limitations. The method that was used is relatively new, and despite its wider use, it is still being developed as a research tool. Furthermore, the NCA method is complementary, rather than competitive, to traditional quantitative methods. Therefore, the collected data in subsequent stages of the research will also be analysed using more scientifically established statistical methods in order to compare the achieved results. It will also allow for, in addition to confirming/negating the results obtained here, another verification of the reliability of the NCA method.

The findings are based on a sample of Polish enterprises. In the future, research should be conducted on a wider sample, including companies not only from developing countries but also from developed economies. This would allow for a comparison of the necessity of the occurrence of conditions limiting the achieved performance levels and further verification and possible development of Visnjic et al.’s [58] theory of the optimal path for deploying exploitation and exploration capabilities in digital servitisation.

In the future, it is also worthwhile to undertake research in finding the relationship between the necessary prerequisites for digital servitisation companies to have exploration, exploitation, and ambidextrous capabilities and performance depending on where the company is located in the supply chain. Such research can provide further insights into the importance of a company’s position in the supply chain in the performance business and competitive advantage derived from digital servitisation. Another possibility is to investigate the impact of digital servitisation on performance, taking into account the relationship between the necessary dynamic capabilities and the dynamics of the environment. For example, it may be more beneficial for companies providing digital services to focus on exploitative capabilities in less dynamic environments and, in dynamic environments, to develop exploratory capabilities. This can contribute to identifying further factors and their configurations that influence success in digital servitisation and overcome the phenomenon of the service paradox.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Vandermerwe, S.; Rada, J. Servitization of business: Adding value by adding services. Eur. Manag. J. 1988, 6, 314–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matusek, M. Service orientation of manufacturing companies in the context of Industry 4.0. In Innovation Management and Information Technology Impact on Global Economy in the Era of Pandemic, Proceedings of the 37th International Business Information Management Association Conference (IBIMA), Cordoba, Spain, 30–31 May 2021; International Business Information Management Association: King of Prussia, PA, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Kowalkowski, C.; Gebauer, H.; Oliva, R. Service growth in product firms: Past, present, and future. Ind. Mark. Manag 2017, 60, 82–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vendrell-Herrero, F.; Bustinza, O.F.; Parry, G.; Georgantzis, N. Servitization, digitization and supply chain interdependency. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2017, 60, 69–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stawiarska, E.; Szwajca, D.; Matusek, M.; Wolniak, R. Diagnosis of the maturity level of implementing industry 4.0 solutions in selected functional areas of management of automotive companies in Poland. Sustainability 2021, 13, 4867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabetino, R.; Harmsen, W.; Kohtamäki, M.; Sihvonen, J. Structuring servitization-related research. Int. J. Oper. Prod. Manag. 2018, 38, 350–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grubic, T.; Jennions, I. Remote monitoring technology and servitised strategies–factors characterising the organisational application. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2018, 56, 2133–2149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rymaszewska, A.; Helo, P.; Gunasekaran, A. IoT powered servitization of manufacturing–an exploratory case study. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2017, 192, 92–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chávez CA, G.; Holgado, M.; Rönnbäck, A.Ö.; Despeisse, M.; Johansson, B. Towards sustainable servitization: A literature review of methods and frameworks. Procedia CIRP 2021, 104, 283–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paschou, T.; Rapaccini, M.; Adrodegari, F.; Saccani, N. Digital servitization in manufacturing: A systematic literature review and research agenda. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2020, 89, 278–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bustinza, O.F.; Gomes, E.; Vendrell-Herrero, F.; Tarba, S.Y. An organizational change framework for digital servitization: Evidence from the Veneto region. Strateg. Change 2018, 27, 111–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kharlamov, A.; Parry, G. The impact of servitization and digitization on productivity and profitability of the firm: A systematic approach. Prod. Plan. Control 2021, 32, 185–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kohtamäki, M.; Parida, V.; Patel, P.C.; Gebauer, H. The relationship between digitalization and servitization: The role of servitization in capturing the financial potential of digitalization. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2020, 151, 119804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- March, J.G. Exploration and exploitation in organizational learning. Organ. Sci. 1991, 2, 71–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coreynen, W.; Matthyssens, P.; Vanderstraeten, J.; van Witteloostuijn, A. Unravelling the internal and external drivers of digital servitization: A dynamic capabilities and contingency perspective on firm strategy. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2020, 89, 265–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bierly, P.E.; Daly, P.S. Alternative knowledge strategies, competitive environment, and organizational performance in small manufacturing firms. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2007, 31, 493–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bustinza, O.F.; Vendrell-Herrero, F.; Gomes, E. Unpacking the effect of strategic ambidexterity on performance: A cross-country comparison of MMNEs developing product-service innovation. Int. Bus. Rev. 2020, 29, 101569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhir, S.; Dhir, S. Role of ambidexterity and learning capability in firm performance: A study of e-commerce industry in India. VINE J. Inf. Knowl. Manag. Syst. 2018, 48, 517–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neely, A. Exploring the financial consequences of the servitization of manufacturing. Oper. Manag. Res. 2008, 1, 103–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raddats, C.; Kowalkowski, C.; Benedettini, O.; Burton, J.; Gebauer, H. Servitization: A contemporary thematic review of four major research streams. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2019, 83, 207–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teece, D.J. Business models, business strategy and innovation. Long Range Plan. 2010, 43, 172–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vargo, S.L.; Lusch, R.F. Service-dominant logic: Continuing the evolution. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2008, 36, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frank, A.G.; Dalenogare, L.S.; Ayala, N.F. Industry 4.0 technologies: Implementation patterns in manufacturing companies. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2019, 210, 15–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tilson, D.; Lyytinen, K.; Sørensen, C. Research commentary—Digital infrastructures: The missing IS research agenda. Inf. Syst. Res. 2010, 21, 748–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F. The digital transformation of business models in the creative industries: A holistic framework and emerging trends. Technovation 2020, 92, 102012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furr, N.; Shipilov, A. Digital doesn't have to be disruptive: The best results can come from adaptation rather than reinvention. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2019, 97, 94–104. [Google Scholar]

- Fischer, T.; Gebauer, H.; Gregory, M.; Ren, G.; Fleisch, E. Exploitation or exploration in service business development? Insights from a dynamic capabilities perspective. J. Serv. Manag. 2010, 21, 591–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lenka, S.; Parida, V.; Wincent, J. Digitalization capabilities as enablers of value co-creation in servitizing firms. Psychol. Mark. 2017, 34, 92–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Reilly, C.A.; Tushman, M.L. Organizational Ambidexterity: Past, Present, and Future. Acad. Manag. Perspect. 2013, 27, 324–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yalcinkaya, G.; Calantone, R.J.; Griffith, D.A. An examination of exploration and exploitation capabilities: Implications for product innovation and market performance. J. Int. Mark. 2007, 15, 63–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, M.E.; Heppelmann, J.E. How smart, connected products are transforming competition. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2014, 92, 64–88. [Google Scholar]

- Kowalkowski, C.; Kindström, D. Service innovation in product-centric firms: A multidimensional business model perspective. J. Bus. Ind. Mark. 2014, 29, 96–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, R.E.; Berthon, P. Market orientation, generative learning, innovation strategy and business performance inter-relationships in bioscience firms. J. Manag. Stud. 2008, 45, 1329–1353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Z.L.; Wong, P.K. Exploration vs exploitation: An empirical test of the ambidexterity hypothesis. Organ. Sci. 2004, 15, 481–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathias, B.D. Exploration, exploitation, ambidexterity, and firm performance: A meta-analysis. In Exploration and Exploitation in Early Stage Ventures and SMEs; Emerald Group Publishing Limited: Bingley, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Raisch, S.; Birkinshaw, J. Organizational ambidexterity: Antecedents, outcomes, and moderators. J. Manag. 2008, 34, 375–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulaga, W.; Reinartz, W.J. Hybrid offerings: How manufacturing firms combine goods and services successfully. J. Mark. 2011, 75, 5–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grönroos, C.; Helle, P. Adopting a service logic in manufacturing: Conceptual foundation and metrics for mutual value creation. J. Serv. Manag. 2010, 21, 564–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zghidi, A.B.; Zaiem, I. Service orientation as a strategic marketing tool: The moderating effect of business sector. Compet. Rev. Int. Bus. J. 2017, 27, 40–61. [Google Scholar]

- Dul, J. Necessary condition analysis (NCA) logic and methodology of “Necessary but Not Sufficient” causality. Organ. Res. Methods 2016, 19, 10–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dettmer, H.W. Breaking the Constraints to World-Class Performance; ASQ Quality Press: Milwaukee, WI, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Storbacka, K. A solution business model: Capabilities and management practices for integrated solutions. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2011, 40, 699–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, R.E.; Strong, C.A. Business performance and dimensions of strategic orientation. J. Bus. Res. 2003, 56, 163–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkatraman, N.; Ramanujam, V. Measurement of business performance in strategy research: A comparison of approaches. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1986, 11, 801–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dess, G.G.; Lumpkin, G.T.; Covin, J.G. Entrepreneurial strategy making and firm performance: Tests of contingency and configurational models. Strateg. Manag. J 1997, 18, 677–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lubatkin, M.H.; Simsek, Z.; Ling, Y.; Veiga, J.F. Ambidexterity and performance in small to medium-sized firms: The pivotal role of top management team behavioral integration. J. Manag. 2006, 32, 646–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, A.K.; Smith, K.G.; Shalley, C.E. The interplay between exploration and exploitation. Acad. Manag. J. 2006, 49, 693–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavie, D.; Stettner, U.; Tushman, M. Exploration and exploitation within and across organizations. Acad. Manag. Ann. 2010, 4, 109–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birkinshaw, J.; Gupta, K. Clarifying the distinctive contribution of ambidexterity to the field of organization studies. Acad. Manag. Perspect. 2013, 27, 287–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Q.; Gedajlovic, E.; Zhang, H. Unpacking organizational ambidexterity: Dimensions, contingencies, and synergistic effects. Organ. Sci. 2009, 20, 781–796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Field, A. Discovering Statistics Using SPSS, 2nd ed.; Sage: London, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Taherdoost, H.; Sahibuddin, S.; Jalaliyoon, N. Exploratory factor analysis; concepts and theory. Adv. Appl. Pure Math. 2022, 27, 375–382. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.F.; Black, W.C.; Babin, B.J.; Anderson, R.E.; Tatham, R.L. Multivariate Data Analysis, 6th ed.; Prentice Hall International: New Jersey, NJ, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Goertz, G.; Hak, T.; Dul, J. Ceilings and floors where are there no observations? Sociol. Methods Res. 2013, 42, 3–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dul, J.; Van der Laan, E.; Kuik, R. A statistical significance test for necessary condition analysis. Organ. Res. Methods 2020, 23, 385–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, M.Y.P.; Lin, K.H.; Peng, D.L.; Chen, P. Linking organizational ambidexterity and performance: The drivers of sustainability in high-tech firms. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castelo-Branco, I.; Cruz-Jesus, F.; Oliveira, T. Assessing Industry 4.0 readiness in manufacturing: Evidence for the European Union. Comput. Ind. 2019, 107, 22–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Visnjic, I.; Turunen, T.; Neely, A. When Innovation Follows Promise: Why Service Innovation is Different, and Why That Matters; Executive Briefing; Cambridge Service Alliance: Cambridge, UK; University of Cambridge: Cambridge, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2022 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).