Abstract

Sustainable human resource management (SHRM) practices are extensively believed to cause a strategic advantage for the hotel industry. However, while a growing body of evidence indicates that SHRM practices are related to superior organization-level outcomes, it is rather unclear as to how these practices could affect such outcomes and whether they result in desirable hotel outcomes. This paper aimed to examine the moderation effect of hotels’ environmental strategy (ES) on the relationship between SHRM practices and hotel business outcomes: operational performance (OP), competitive advantage (C), and corporate performance (CP). Following a positivism philosophy, a proposed hypothesised model was validated through a survey strategy. Data were obtained from 247 green-certified hotel managers based in Egypt’s top-two major cities involving green-certified hotels. Structural equation modelling was used to test the model relationships. The findings lent credence to the significant connectedness between SHRM practices and hotel business outcomes. The moderation effect of ES was positively confirmed by 83.4% of the SHRM practices, demonstrating that ES is a crucial driver of hotel business outcomes through the optimal usage of SHRM. Negatively, it was revealed that only sustainable promotion practice (16.6%) does not moderate its impact on the hotel business outcomes. This research is the first empirical study to examine the moderation effect of ES on the nexus between the SHRM and hotel business outcomes in the green-certified hotels of Egypt.

1. Introduction

The trend toward sustainable practices in the hotel industry has become imperative, attracting scholars’ attention during the COVID-19 era. Today, the industrial and service world in general, and the field of hotel business in particular, is witnessing a growing interest in environmental issues and a rapid shift towards cultural awareness in the sustainable environment in light of the ever-increasing cognitive and behavioural awareness of the dangers of negative consequences caused by the problems and difficulties of industrial and production pollution, industrial waste, and the tremendous waste of natural resources [1,2]. Significant attention has been paid by governments and non-governmental organizations worldwide, warning of the grave risks to humanity resulting from environmental pollution and its impact on most aspects of life, and establishing the endeavour to raise the necessary awareness regarding the environment. There are many calls for businesses to be more sustainable than they have been traditionally [3] by transforming their usage of resources intelligently to achieve value. Nowadays, hotels invest in diverse sustainability practices to obtain returns [4]. Similarly, sustainable human resource management (SHRM) is a modern system within administrative thought, demonstrating its ability to shape positive hotel business outcomes [5].

Most service-oriented organizations in general, and hotels in particular, seek to play their primary role, related to meeting the community’s needs, to provide suitable goods and services through proper exploitation of various natural resources and adaptation with the human, social, economic, and environmental dimensions. Thus, to achieve this, these institutions witness the necessity of providing a culture of concern for the responsible environment by completing various organizational functions within the environmental management system [2]. Where the concept of SHRM is one of the terms that researchers deal with to clarify the relationship between HRM and its interaction with the surrounding environment, attention should be paid to the need of reflecting this on reasonable practices in an organization to boost performance [6].

Scholars are still trying to clarify and define the SHRM concept and practical activities and work to create the appropriate mix of environmental and organizational performance issues and business strategies, increase opportunities for organizations, and adapt them to the external environment to achieve competitive advantages [7]. The SHRM goes beyond the social responsibility of organizations [8]. It plays an integral role in solving problems related to the environment by training employees regarding the requirements of implementing laws related to environmental safety [9]. Furthermore, SHRM practices are extensively believed to cause a strategic advantage for the hotel industry [7]. However, there is a sufficient body of evidence indicating that SHRM practices are related to superior staff-level outcomes. On the contrary, screening their effects on employer-level outcomes is still under research [8].

Despite SHRM’s significance, this domain is still “at its development stage” [7] (p. 295). The literature consists of many investigations on the link between SHRM and employee-related outcomes [8,10,11,12,13]. On the contrary, scant empirical research reveals the connectedness between SHRM and the hotel organization-related outcomes (e.g., corporate performance, competitive advantage) [8].

A research gap emerged from this study in terms of knowing how and which SHRM practices could affect work-related outcomes, and whether these practices result in desirable hotel business outcomes. Therefore, this paper revealed how and when SHRM practices influence the hotel business outcomes: operational performance (OP), competitive advantage (C), and corporate performance (CP) using the moderation mechanism of environmental strategy (ES).

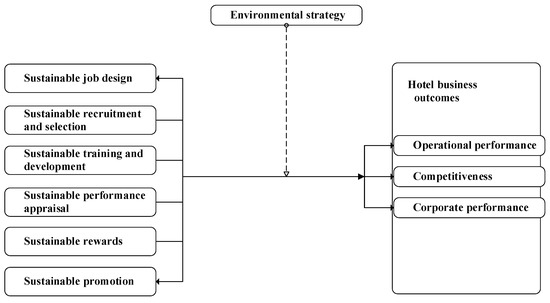

Following the calls for additional consideration of the connectedness between SHRM and hotel non-employee outcomes [7,14,15], this study aimed to explore the relationship between the perceived SHRM practices, ES, and hotel business outcomes from the perspective of the green-certified hotel managers in Egypt. Consequently, this research offered contributions to the related literature on sustainability and HRM in the hotel industry. First, it developed a conceptual model shaping the relationships between SHRM and hotels’ business indicators through the ES moderator. This framework used the social exchange theory (SET) to interpret the connectedness between SHRM and hotel business outcomes. Our model used the SHRM that involved six sets (sustainable job design, sustainable recruitment and selection, sustainable training and development, sustainable performance appraisal, sustainable rewards, and sustainable promotion) regarding enhancing our understanding of how sustainability could be integrated with the traditional human resource management (HRM) practices that boost the hotel business outcomes. Second, our results supported a good model fit, explaining acceptable variance levels in OP, C, and CP. Therefore, scholars could use this developed model for further investigations. Third, hotel managers could benefit from this study by motivating their staff to better practice the SHRM to boost their performance.

This paper is structured as follows: the literature portion is concerned with the study factors and the developed framework. The methodology section reports on the instrument that was used. The results and discussion then follow. The last part demonstrates the conclusion and research implications.

2. Review of Literature

2.1. The Underlying Theory and Hypotheses

The conceptual framework used the social exchange theory (SET) [16] to investigate the causal relationships between the independent and the dependent factors. This philosophy elucidates human performance and the consequence structure of its relations. It proposes that hotel staff tend to respond to their hotels with extra-role activities when they feel their workplace is investing in them. When staff obtain sustainable resources in the workplace, they feel the duty to indemnify their hotels with superior performance [17]. Therefore, SET was selected to understand how the green-certified hotels achieve superior outcomes in terms of performance and competitive advantage using SHRM and then receive value in return to their organization(e.g., OP, C, CP).

2.2. Sustainability and the HRM Connection

Formerly, there had been growing attention on HRM due to its effect on organizational performance [18]. Regardless of its advancement, many businesses still plan, manage, and organise the HR function, believing it represents a cost to the company [8]. Strategic HRM aligned to financial outcomes is insufficient. HRM is essential to support sustainable firms. It is also needed to support beneficial results related to economic aspects and cultural and ecological firm performance. Accordingly, a new HRM approach called the SHRM, or the green HRM, has been adopted to keep any firm sustainable. The SHRM is primarily connected to long-term changes in businesses and societies [19].

It has been demonstrated that sustainability is a people concern. Sustainability influences a firm’s behaviour and culture. It affects the communication system, companies’ practice in recruiting, how organizations engage and retain employees, how they train employees and communicate with customers, and the brand and value proposition. For that concern, HR ought to be necessary in any firm’s sustainability initiatives. HRM employees must act continuously as the organizational leaders as it pertains to sustainability. HRM creates rules and sets methodologies, develops training programmes, leads employee communications, and sets sustainability measurements [20]. Sustainability-oriented thinking is turning out to be a part of HRM development. Sustainable HRM aims to achieve organizational sustainability by developing HRM policies, strategies, and procedures that support the economic, social, and ecological dimensions [21]. In this context, a model to accomplish superior performance by dealing with a sustainable approach through socially responsible practices, innovation in procedures and products/services, diversity management, the inclusion of environmental management initiatives, and initiating the HRM in central organizational sustainability was recommended [22].

SHRM is the corporate function that reveals the best potential to include a sustainability attitude at the firm’s executive level. This way, a connection to HRM development is anticipated through green and sustainable thinking [23]. Despite the prominence of SHRM and its impact on organizational outcomes, some scholars claim that the research conducted so far in the functional area of HRM and sustainability is insufficient [7].

2.3. Sustainable Human Resource Management (SHRM) Definition, Framework, Practices

Understanding the concept of SHRM and its approaches is vital to examining how HRM can achieve success. Accordingly, to analyse and understand SHRM’s nature, the related issues and challenges surrounding what is intended to be performed are relevant to assess HRM’s role in sustainability orientation.

The literature on SHRM has recently developed, representing an attempt to cope with the nexus between HRM practices and outcomes beyond financial consequences [9]. However, many disciplines have published much diverse and fragmented research regarding the SHRM concept. There is no single and specific definition of that term, and it has been practised in a variety of ways for numerous purposes. Generally, it has been initiated to refer to social and economic outcomes that contribute to the firm’s permanence in the long-term. It has also been referred to as HRM activities that enhance positive environmental results (e.g., green initiatives, positive social and financial outcomes).

Regarding the historical background of the SHRM concept, it was rooted in many research avenues: corporate sustainability research, corporate social responsibility research, sustainable works systems research, traditional or strategic HRM research, and ergonomics and human factors research [7,24]. The terms green HRM, eco-friendly HRM, responsible HRM, and SHRM have been used interchangeably in the previous literature [19,25]. Although these terms differ in how they attempt to achieve the goals of economic branding, positive social/human outcomes, and environmental results, they are all focused on acknowledging, both explicitly or implicitly, social and economic firm outcomes. They all recognise HR outcomes’ impact on endurance and a firm’s success in general. Turning to the hotel industry, Zaki [26] guaranteed a high-performance level when hotels acclimatise to environmental predictions.

There are numerous definitions for the term SHRM. One of the most popular definitions was rooted in 2009 as a form of intended or evolving HR policies and procedures that enable a firm to complement its aims over time [27]. The idea of decreasing the undesirable effect on the environment, humans, and societies was added and acknowledged the critical enabling role of headquarters, middle and line managers, HRM experts, and employees [9]. However, three main characteristics could be concluded in the attempts to define SHRM: first, the focus is on developing employees/the human capital as a vital outcome of HRM practices; second, SHRM does challenge the idea that the principal HRM’s aim is the accomplishment of business goals; third, a leading concern is long-term success using responsible HRM practices and strategies to contribute to this success [28]. Most definitions of SHRM were related to long-term understanding of a firm’s success and organizational sustainability [18].

The HR function has a dominant role in the hospitality context. It can motivate the inclusion of sustainability initiatives in the scope of the various relationships inside a firm and with other market rivals [8]. In general, the term SHRM has demonstrated great resonance, with its increasing importance evident within the hotel business environment. It represents the overall policies to promote the sustainable use of available resources within hotels and focus on a sustainable environment. It is also a key element in enabling different organizations to integrate the objectives of HRM with the organization’s environmental management, so it works to improve green empowerment that contributes to increasing employee participation as it pertains to work areas. Accordingly, SHRM includes multiple activities, such as analysis and description of sustainable jobs, sustainable HR planning, sustainable recruitment, sustainable selection, sustainable training, other performance evaluation, and sustainable benefits [7].

It could be concluded that SHRM practices are generally considered traditional, and there can be a variety of sustainable functions under each. SHRM practices include: appointing staff with a concern for sustainable initiatives appraising, providing directed training for raising awareness and skills needed for employees’ behavioural changes, evaluating the socially responsible performance of employees, rewarding employees who contribute to the environmental initiatives, and giving priority of employment to persons from the local community [6]. Currently, hotels are increasingly adopting SHRM practices due to external stakeholders’ pressure.

Since the research model’s theoretical underpinnings were based on SET theory, we argued that the hotels that practice proper SHRM would, consequently, ensure positive business outcomes. The following practices are a simplified explanation of SHRM practices based on our hypothesised framework (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

The study framework.

2.3.1. Sustainable Job Design (SJD)

The sustainable design of any job expresses the process that aims to determine the content of the responsible tasks of the position and the qualifications of its occupants. It leads to the achievement of the environmental goals of the hotel organization on the one hand and to fulfilling the desires of the responsible employee on the other hand, taking into account the type of technology used to achieve sustainable environmental performance. In addition, there are decent jobs that contribute to preserving or restoring the quality of the environment, whether these jobs are industrial, service, commercial, agricultural, or administrative [28]. These jobs have a role in reducing emissions and pollution, protecting the ecosystem, and, finally, enabling communities and organizations to adapt to environmental changes [29]. Recently, it was confirmed that SHRM enhances the hotel’s capability for innovation and then impacts its reputation and customer satisfaction [18].

In summary, sustainable job design is considered the first SHRM practice to employ a suitable job candidate with sufficient knowledge and awareness of sustainability dimensions. Therefore, we theorised that:

Hypothesis 1.

SJD practice has a positive effect on a hotel’s operational performance.

Hypothesis 2.

SJD practice has a positive effect on a hotel’s competitiveness.

Hypothesis 3.

SJD practice has a positive effect on a hotel’s corporate performance.

2.3.2. Sustainable Recruitment and Selection (SRS)

Recruitment activities are established to work within hotels to provide as much information as possible about the requirements of the vacant job, the nature and type of the job, and encourage the proper selection and appointment of job-seeking individuals who have suitable experience, skills, methods, and behaviours. The hotel organization can rely on individuals concerned with the environment and the usual employment standards related to the specific duties of the related job [10].

In terms of aiming to construct a sustainability-oriented workforce, hotels have two options: (1) depending on sustainable recruitment, or (2) providing critical related awareness, learning, training, and development to the existing employees. However, focusing on sustainable recruitment is more cost-effective than providing sustainable knowledge and training to the existing employees. Therefore, searching for the best sustainable recruitment practices is essential to any hotel that is concerned about sustainability. Some hotels integrate social responsibility schemes with the recruitment strategy in the recruitment context in addition to a potential employee demonstrating a commitment to working in a sustainability-oriented company [8].

It has been well noted that becoming a socially responsible employer improves employer branding, the organization image, and is a valuable way to attract potential employees who have a social responsibility concern [14]. Some hotels are starting to recognise that image acquisition as a sustainable firm is an effective way to attract new talents [30]. Certainly, socially responsible employers can attract talented staff that they require to implement corporate sustainable management advantages, and, ultimately, it contributes to achieving the hotel’s sustainability goals [31,32].

Some hotels consider candidates’ social orientation as a primary criterion for job vacancies regarding the sustainable selection practice. Hoteliers’ queries related to social responsibility are often posed in the selection pool interviews [33]. Hiring staff with outstanding capabilities, skills, orientations, and green preparations contributes to achieving the organization’s goals, including environmental sustainability. Therefore, SRS integrates environmental dimensions into employment policies and strategies. Job interviews should be consistent to assess the potential fit of candidates with the organization’s sustainable programmes. Hence, we could argue for the following hypotheses:

Hypothesis 4.

SRS has a positive effect on a hotel’s operational performance.

Hypothesis 5.

SRS has a positive effect on a hotel’s competitiveness.

Hypothesis 6.

SRS has a positive effect on a hotel’s corporate performance.

2.3.3. Sustainable Training and Development (STD)

The sustainable training process is mainly settled by transferring the proper knowledge and skills regarding improving sustainability [1]. Appraisal systems should support training to integrate with the hotel’s sustainability goals. The sustainability perspective emphasises the benefit of the training practice to hotel employees. The sustainable training provides environmental preparations for employees and managers to develop their ecological patterns, skills, and knowledge. Some cases represent the sustainable training nature, such as providing training to learn the best environmentally friendly methods or adapting to such green activities and applying job rotation as a tool for future leadership development for green environment managers. As a result, the corporate sustainable management programmes’ implementation will be adhered to [14].

Providing sustainable training for new staff encourages employees to participate in volunteer projects. These projects enhance employees’ knowledge skills and extend comprehensive development programmes to prepare employees for future responsibilities [6]. A sustainable education culture that will change the attitudes and behaviours of employees is required for the hotel’s success [8]. For example, every staff member goes through eco-awareness training concerning environmental sustainability programmes in some hotel chains. The hotel staff receive education on the green aspects of their products/services. Some hotels celebrate their annual sustainable or green day by organizing many competitive programmes. Teaching certain vital eco-principles between staff and management members is an excellent practice.

Sustainable training and development practices require an adequate understanding of the market, governmental, and societal requirements. They generate a sustainable advantage by focusing on green innovations, hotels providing new technologies, providing the market with more efficient and effective products, and provoking changes in their business models [33].

STD practices involve social analysis of workplace workshops, job rotations, socially responsible management models, staff welfare training, job-related health and safety measures, work regulations, equality, and employee rights [34].

Without proper training and development, materializing hotels’ sustainable image is challenging. Therefore, specific hotels have learned the importance of socially responsible education, training, and growth in their organizational context. Notably, some hotels seriously started to analyse their sustainable training needs to help the staff to become a more socially accountable and concerned workforce. Based on sustainable training needs analysis, these hotels conduct serious and systematic education, training, and development programmes with the employees to provide needed knowledge, skills, and attitudes for good sustainable management [35]. In line with prior justifications, we hypothesised the following:

Hypothesis 7.

STD has a positive effect on a hotel’s operational performance.

Hypothesis 8.

STD has a positive effect on a hotel’s competitiveness.

Hypothesis 9.

STD has a positive effect on a hotel’s corporate performance.

2.3.4. Sustainable Performance Appraisals (SPA)

Sustainable management is characterised by being keen to urge and encourage the hotel employees such that their needs are compatible and consistent with the hotel’s orientation towards preserving the environment [36]. Evaluating the staff performance in fulfilling their responsibilities involves spreading the knowledge of environmental learning. The measurement criteria of employees’ socially responsible performance must be carefully aligned with the hotel’s sustainable performance standards [37].

Incorporating corporate sustainable management objectives and aims with the performance appraisal system is necessary for hotels to ensure a positive image among rivals. Hotels should include sustainability issues and socially responsible incidents, take-up of social responsibilities, and the success of communicating sustainability concerns and policy within the performance evaluation system [38].

Installing sustainable performance standards, or KPIs, into the performance management system is inadequate. Communication of sustainable schemes, KPIs, and benchmarks to the hotel employees through regular performance evaluations is also needed to materialise targeted sustainable performance [39,40].

Hotel managers should establish sustainable targets, goals, and procedures for their staff. They should assess tolerable incidents, practice social responsibility, and successfully communicate the hotel sustainability strategy within the scope of their daily operations [29,41]. Consequently, the following arguments were drawn:

Hypothesis 10.

SPA has a positive effect on a hotel’s operational performance.

Hypothesis 11.

STD has a positive effect on a hotel’s competitiveness.

Hypothesis 12.

STD has a positive effect on a hotel’s corporate performance.

2.3.5. Sustainable Rewards (SR)

The sustainable reward is a crucial function of the SHRM. Sustainable reward management contributes to corporate sustainable management initiatives by motivating employees. Hotels use monetary (e.g., salary bonus, extra incentives, tipping) and non-financial rewards (e.g., recognition, motivation, social incentives, and honours), impacting corporate performance [33].

Some organizations have recently rewarded extraordinary performance by including the sustainability criteria in their salary appraisals. The non-financial rewards of sustainable performance are used instead of financial compensations. The success of the non-financial rewards depends on the prominence of organization-comprehensive labelling, which increases employees’ awareness of sustainability achievements [31].

There are many types of sustainable reward and compensation practices (e.g., customised packages to reward sustainable skills achievement, financial/non-financial sustainable management rewards, personal reward plan to gain sustainable social responsibility, linking staff partnerships in sustainability plans with the reward system) [35,37].

Providing rewards for innovative sustainable performance is highly recommended to promote staff innovation. Therefore, some hotels started to offer spurs to motivate waste and recycling management, support flexible work schedules, and address other sustainability matters [14]. Accordingly, the following arguments were delineated:

Hypothesis 13.

SR has a positive effect on a hotel’s operational performance.

Hypothesis 14.

SR has a positive effect on a hotel’s competitiveness.

Hypothesis 15.

SR has a positive effect on a hotel’s corporate performance.

2.3.6. Sustainable Promotion

Motivation or incentives are among the essential HRM practices through which hotel employees are rewarded for their performance. This practice is the most potent and optimal way to link employees and the organization’s interests and is relevant in supporting environmental management to develop services and innovations.

The critical role of sustainable motivation and promotion practices is to ensure a socially responsible workplace. It means that a workplace is environmentally sensitive, resource-efficient, and socially accountable [28]. There are some hotels where the traditional motivation and promotion purpose was extended to include socially responsible management. These hotels have continually created various socially responsible initiatives to reduce the employee stress caused by harmful work environments. Future advancements are necessary to ensure further feelings of employee motivation. Since most new hotel employees are career-minded, ambitious, and looking for fast growth, their career advancement is the prime motivating factor for their managers [34]. New hotel staff want to know where their occupations will be going. Thus, career management importance has gained growing recognition [32]. The sustainable development viewpoint is that employees perform better when they feel trusted. Corporate growth plans should be highlighted to all staff to increase their understanding and commitment. Sustainable promotion essentially means helping the employees plan their careers based on their capabilities within sustainable organizational needs. It implies that, after capabilities awareness, career opportunities, and development opportunities, the employee chooses to develop him- or herself in a direction that improves his or her ability to handle new tasks [42]. Several hotels have worked out career paths and linked promotion programmes to career planning development to enhance their SHRM practices [14]. Thus, the following hypotheses were outlined:

Hypothesis 16.

SP has a positive effect on a hotel’s operational performance.

Hypothesis 17.

SP has a positive effect on a hotel’s competitiveness.

Hypothesis 18.

SP has a positive effect on a hotel’s corporate performance.

2.4. Environmental Strategy (ES) as a Model Moderator

The ES is a corporate philosophy adopted by some hotels referring to how they follow a strategic planning approach, starting from adopting an environmental vision, mission, and green goals [43]. The ES mixes employees’ awareness and knowledge of the sustainable corporate orientation. Hotels’ ES involves green and sustainable key performance indicators. Hotels that adopt an environmental management system have a sustainable culture and the so-called ES [44].

ES is a crucial driver of a hotel’s performance. Hotel employees and managers could develop the ES through their environmental commitment and involvement in sustainable behaviour [45]. Hotels that create an ES guarantee employee sustainable behaviour, enhancing hotel performance [46].

The impact of SHRM in shaping the green behaviour of tourism employees is still under research [43]. He found that SHRM positively impacts the citizenship environmental behaviour; that is to say, ES improves the green organization behaviour, which, in turn, results in performance gains being attained [47]. The theoretical ground can be seen through the relationship to the SET theory. Employees with an environmental culture are more likely to be involved in extra-role behaviours through higher performance levels that will lead to positive organizational outcomes [48]. Overlooking the previous justifications, we could argue that, when the ES is high, the relationship between SHRM practices and the hotel business outcomes will be strong.

Hypothesis 19.

The ES moderates the influence of SHRM practices and the hotel business outcomes. As the ES becomes stronger, a positive impact of SHRM practices on hotel business outcomes is significant.

2.5. Hotel Business Outcomes

Due to the severe competition among hotels, developing a personalised image has become critical for most hotel owners. The well-expressed image plays a dominant role in the positioning schemes. Hotels do their best to maintain an image positioning and develop their core competitiveness depending on environment-based strategies and unique HRM practices. Studies on hotel image formation have recognised the outstanding service characteristics in defining the primary attributes of their image [49]. Chain hotels have been among the most incredible and profitable hotels worldwide. However, they are considered the most sensitive market segment [15]. In this regard, this research hopes to help hotel managers maintain their business performance without deterioration by using effective SHRM practices. Hotel success is determined by the corporate image and performance [50,51].

This research argued that corporate performance would not shrink when hotel managers practice a sound SHRM. In line with the marketing literature, business outcomes are seen as a multi-faceted and subjective dimension, meaning that they involve several perceptions of diverse persons. Therefore, hotel business outcomes are operationalised in this research as a multi-dimensional aspect of operational performance (OP), competitive advantage (C), and corporate performance (CP), similar to previous approaches [52]. The OP measure is operationalised as a hotel’s ability to minimise the total operating costs associated with waste handling and customer complaints. The C measure is operationalised as a hotel’s ability to improve its image and increase employee and customer satisfaction owing to practising SHRM activities. Corporate performance is operationalised as a hotel’s ability to increase sales, profits, and the market percentage or market penetration index due to practising SHRM practices.

3. Research Methodology

3.1. Population, Sample, and Data Collection

Egypt has seventy-six green-star-certified hotels (GSH), mainly supporting one of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change goals (UNFCCC: SDG11). The GSH is considered a new scheme for capacity-building, offering a national green certification. The Egyptian Hotel Association (EHA) and the Egyptian Ministry of Tourism duly manage this programme. It provides an opportunity for hotels based in Egypt to be internationally recognised for being eco-friendly organizations by maximizing their performance and sustainability principles while reducing operational costs without affecting the quality standards. Many certified experts around the globe guide interested hotels through training and continuous support meetings to field audits to certify obedience to the programme criteria before granting a GSH accreditation [53]. The selection of GSH is based on the fact that these hotels are of potential environmental orientation and sustainability adaptation due to their nature instead of other hotels. Therefore, our examination of the moderation effect of ES on the nexus between SHRM and the hotel business outcomes would be supportive.

Most of the GSH (24%, 8%) are based in El-Gouna and Hurghada. The majority of them ranged from 4-star to 5-star hotels. El-Gouna has 16 GSH, and Hurghada has 10 GSH. The remaining GSH in Egypt are located in other regions, such as South Sinai of Egypt, Safaga, Cairo and Alexandria, Marsa Alam, and Matrouh [53].

Due to the hotel’s accessibility to the research team, we considered a non-probability convenience sample of hotel managers working in Hurghada (n = 10) and El-Gouna (n = 16) GSH. They were both honoured by the Egyptian Ministry of Tourism as socially and environmentally responsible cities. Therefore, the hotel sample involved 26 green hotels based in the cities of El-Gouna and Hurghada, and all agreed to participate in this study.

To achieve the research objectives, the target study subject was all the hotel managers working in Hurghada and El-Gouna GSH with an HR association (e.g., primary hotel managers, associate hotel managers, HR managers, room’s division managers, front office managers, operation managers, executive chefs, sales directors, restaurant managers, food and beverages managers, sales and marketing managers, front office assistants, and other department head positions). A managerial perspective is an appropriate way to check if the hotel poses interest in the application of SHRM or not [14]. A self-administrated questionnaire was developed and distributed to the GSH sample from October 2021 until January 2022. A personal connection approach with hotel managers facilitated the data collection procedure. Most hotel managers graduated from tourism educational institutions in Egypt, where 50% of the research team worked. Therefore, this simplifies the communication with them. Hotel managers were given the survey for research and then were asked to meet their executive staff to share and distribute the survey. Informed consent was then then assembled. A total of 312 surveys were equally disseminated through the hotel sample; 12 copies per hotel and 247 usable copies finally constituted the sample size of 79.2 response ratio. Based on the indicators of GPowerWin 3.1.9.7 software (e.g., effect size, power, number of DVs), a sample size of 247 is more than sufficient to use the PLS-SEM [54].

3.2. Research Philosophy and Research Instrument

Since the research methodology was initially set according to the positivism paradigm, it assumes that the researcher makes an objective analysis and interpretation of the data collected [55]. In other words, a positivist research philosophy supposes that researchers deal with issues objectively without influencing the real problem being studied. Furthermore, this philosophy believes that the final output can be law-like generalisations, similar to the results obtained by physical and natural scientists. Thus, investigators in such a paradigm separated themselves from the investigated phenomenon [56].

The final questionnaire layout comprises 67 closed-ended questions. It takes about 40 min to be completed. It has granted participants the right to be fully informed about the research and the right to privacy concerns. Voluntary participation and the freedom to withdraw at any time were established. It also used follow-up emails and telephone calls to engage them to join. A pilot test was performed on 15 academics to test the questionnaire layout. Piloting results guaranteed a complete understanding of respondents to the survey questions.

The questionnaire involved four parts. The first part encloses a cover letter to clarify survey purposes, essential contact information, and respondent and hotel demographic data. The second part was designed to obtain the respondent’s perceptions of SHRM practices (6 main factors, 44 variables) based on a five-point Likert-type scale (5 = strongly agree; 1 = strongly not agree). It was developed based on reliable and valid scale measures of previous literature with specific wording amendments to achieve the research purpose [5,12,57,58,59,60]. The third part was designed to obtain the respondent’s perceptions of the environmental strategy. Environmental strategy measures (6 variables) were adapted from Refs. [44,46,47]. The final part was denoted for the hotel’s indicators of business outcomes (OP, C, and CP). The operational performance is operationalised as a hotel’s ability to minimise total costs associated with waste handling and customer complaints. The competitiveness is operationalised as a hotel’s ability to improve its image and increase employee and customer satisfaction owing to practising SHRM activities. Corporate performance is operationalised as a hotel’s ability to increase sales, profits, and market percentage or market penetration index due to practising SHRM practices [52].

3.3. Data Analysis

Survey investigation was executed by building and testing the measurement and structural models [61]. We conducted the structural equation modelling (SEM) using PLS 3 to check study dimensions and explore the relationship among model variables. PLS path modelling represents a well-substantiated tool for estimating complex cause–effect relationship models [54,62]. PLS-SEM can be employed for a small sample size as it generates better results because of having higher statistical power [61]. Coinciding with the Kline rule, four to five cases for each item are adequate for multivariate analysis [63]. The current study survey contains 59 indicators measuring two primary constructs (44 observed items for the latent SHRM factor and 15 items for hotel business outcomes indicators); hence, n = 247 can be considered an appropriate sample size for SEM analysis. Therefore, our usage of PLS-SEM is based on various reasons, including a smaller sample size and the use of latent indicators [61,64].

4. Results

PLS-SEM is considered an innovative technique primarily used for model dimensions predictions. It is run by fewer requirements than other techniques regarding sample size and the normal distribution condition [61]. Therefore, the PLS algorithm and bootstrapping methods were executed to highlight factor loadings, path coefficients, and significances [65]. First, the measurement model was arbitrated, and the structural model assessment was then performed.

4.1. The Sample Outline

Table 1 displays the respondents’ profiles.

Table 1.

Respondents’ characteristics.

Table 1 shows that, out of the 247 participants, 76.5% (189) were male and about 7% (17) were female, confirming that these hotels hire limited proportions of females [66]; about 17% did not prefer to disclose their gender. The results show that most of the respondents were 35 to 45 years old, 39% (97), while 35% (86) were less than 35 years old; the remaining 4% (10) were 55 to 60 years old. Regarding their education, 85% (210) of the managers had university degrees, 7% (18) had intermediate education, 6% (14) had only secondary school degrees, and 2% (5) had post-graduate education degrees. Regarding their hotel department, 79% (195) of the respondents were from HR, 11% (26) were head executives, and 11% (26) were the general hotel managers or their associates. The majority of the hotel managers, 41% (100), had worked in hotels for 10 to 20 years. The managers who worked in a five-star hotel represented the highest percent (70%), followed by those based in four-star green hotels.

4.2. The Measurement Model

Before testing the measurement model, descriptive analyses (e.g., means, deviations, t-statistics, and normality) and correlations between all the variables were first executed (Table 2). The kurtosis and skewness calculations showed no issue related to the normality. The correlations matrix showed positive relationships among the variables.

Table 2.

Descriptive statistics and correlations.

The measurement model was arbitrated, and convergent validity was assured using lambda loadings, average variance extracted (AVE), and composite reliability (CR). All the study variables (Table 3) were loaded to their related factors, showing scores above 0.50 to indicate reliable constructs. Likewise, the CR scores exceeded 0.70, which is acceptable. All the AVE scores exceeded the recommended cut-off value (0.5). Variance inflation factors (VIF) were also assured such that no common method bias exists [67]. Common method bias was not observed in this study as all the VIFs were less than (3.5), demonstrating that no common method bias exists.

Table 3.

The measurement model statistics.

The convergent validity is confirmed since the AVE values and lambda scores were more than 0.5 (Table 3) [61,65].

The heterotrait–monotrait ratio (HTMT) [62] was used to support the discriminant validity [61]. All the HTMT values (Table 4) were lower than 0.80, confirming a discriminant validity achievement.

Table 4.

Discriminant validity.

4.3. The Structure Model

Once the measurement model was assessed, the structure model was then evaluated. A PLS-SEM path analysis was performed to test the model hypotheses (Table 5). Notably, the model explained 0.70, 0.62, and 0.76 of the variance in the OP, C, and CP factors, respectively, demonstrating reliable model constructs. The model fit was evaluated by checking the path parameters, t-statistics, and the significance level (p < 5%, t > 1.64). The model fit indices (χ2 = 1200.20, df = 514, p < 0.001, RMSEA = 0.08, GFI = 0.87, CFI = 0.95, IFI = 0.96, TLI = 0.90) demonstrated a model fit [68].

Table 5.

Hypotheses testing.

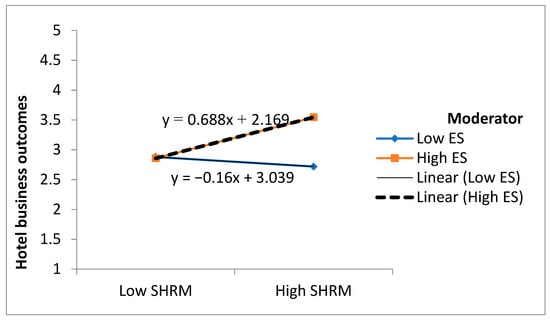

Regarding testing the moderating effect of ES, two techniques were used to check the interaction between the variables. First, the high and low moderation models were employed to decide if ES moderates the impact of SHRM practices on the hotel’s indicators (OP, C, and CP) or not, based on four measures (Table 6), to judge the moderator role through variance in path parameters among subgroups, standard error (SE), the critical ratio (CR), and the significance level (P value) [69]. The results of Table 6 highlight that ES moderated the effect of the five SHRM practices (SJD, SRS, STD, SPA, and SR) on the hotel business outcomes indicators (OP, C, and CP). However, the ES did not moderate the SP/hotel business outcome relationship. In other terms, our findings mostly confirmed that ES shaped the hotel’s indicators (OP, C, and CP).

Table 6.

The moderation effect.

Second, an Excel tool was also used to determine (Figure 2) the moderation effect of ES on the relationship between SHRM practices and the dependent factors. ES strengthened the positive relationship between SHRM and hotel business outcomes. The higher the ES, the more significant the positive effect was of SHRM on hotel business outcomes.

Figure 2.

The moderation effect of ES.

5. Discussion

This study is the first to ascertain the moderation mechanism for the impact of SHRM bundles on the green-certified hotels in two prominent cities of Egypt that involve the majority of GCH. The hotel’s management perspective was followed to obtain their ergonomics perceptions, as recommended by the authors of Ref. [18]. Following their recommendations, a holistic conceptual framework (Figure 1) was developed [7]. Most of our outlined hypotheses were supported; all the SHRM practices were positively associated with the hotel business outcomes (OP, C, and CP). Consistent with the existing literature, this study’s hypothesised model lends credibility to prior investigations among SHRM and the hospitality outcomes [8,70]. However, the nexus between SHRM and the hotel’s business indicators in the context of the Egyptian GCH were examined for the first time to the best of the authors’ knowledge.

Our results coincided with those of the study cited in Ref. [48], whose authors recommended the usage of multiple bundles of SHRM practices rather than one practice to maintain a positive organizational outcome. However, their context was the oil and gas sector, which is different from ours. Furthermore, we benefited from the [71] comprehensive view of using many practices of SHRM in the Egyptian tourism sector.

Interestingly, our findings extended the prior effort of the study in Ref. [14] by using a bundle of six SHRM practices rather than four. Furthermore, our results contradict that study [14], whose authors found a significant negative association between SHRM and performance in Malaysian hotels; arguably, our findings confirmed the positive SHRM and performance relationships in the Egyptian context.

The results of the moderation effect in the current study found a negative ES moderator of the impact of SP practice on the hotel business outcomes. This notion contradicted the study in Ref. [72], whose authors found this path direction relationship to be a positive moderator.

6. Conclusions

Following the call of the authors of Ref. [3], initiating sustainable business models into the service sector is essential to ensure the optimum resources reservation and help the management to best benefit from these efforts. This study extended their [3] work by suggesting the SHRM adoption in hotels. The SHRM application here in this study could be adopted by service organizations. Our SEM findings are in line with the SET theory to further explore the employee–hotel relationship. A win–win approach indicates that the proper SHRM application ensures positive business outcomes [17].

In line with the previous discussion, we concluded that the investigated bundles of SHRM practices (SJD, SRS, STD, SPA, SR, and SP) were positively related to the hotel’s outcomes indicators (OP, C, and CP). As the β values were less than 5% and the t-scores were above 2.89, this indicates that all the hypotheses (H1:H18) were accepted. Moreover, the results of the moderation effect based on the model paths (Table 6) confirmed that the environmental strategy moderated the relationship between the five SHRM practices (SJD, SRS, STD, SPA, and SR) and the hotel business outcomes indicators. However, only one exception appeared to refute the ES as a significant moderator of the impact of SP on the hotel business outcomes. The SP means helping hotel staff plan and schedule their future careers due to their capabilities within sustainable hotel needs, making them talented enough to complete their work tasks effectively. Then, their customer service will be imminent [31,42]. Our justification for this result might be due to COVID-19’s impact. The SP practice in the COVID-19 era has been changed as the outbreak continues. Many hotel employees become depressed due to their fears of COVID-19 or their anxiety regarding pausing their careers [73]. Therefore, this outcome opens the door for future analysis of the nexus between SP and hotel business outcomes after the pandemic.

6.1. Theoretical Implications

Since it has been argued that additional research is required on both the SHRM context and the hospitality-business-related outcomes [14,18], this study offers some contextual contributions. The existing research on the SHRM practices–hotel managers’ behaviours association has failed to scrutinise the mechanisms of knowing how amply and when SHRM practices affect specific hotel business outcomes (e.g., CP, C, and OP). Therefore, the current study has contributed to the HRM literature by unfolding the impact of ES orientation on the nexus between SHRM and hotel business outcomes. This research used the SET to interpret how SHRM could predict hotel business outcomes rather than the employee outcomes. A re-examination of the nexus between the SHRM and GSH outcomes was performed for the first time through this study through the ES moderator. Therefore, a gap in the hotel literature was filled by explaining the nexus between SHRM and the organizational developments in the Egyptian GSH context. This research revealed that ES mostly moderated the connection between SHRM and hotel business outcomes variables. The usage of PLS-SEM guided us to know when and how SHRM could affect some hotel business outcomes.

Furthermore, this study developed and tested a conceptual model that shaped the relationships between SHRM and hotel business outcomes through the ES moderator. This model used comprehensive SHRM practices, following the recommendation of the authors in Ref. [7], to enrich our understanding of how sustainability could be combined with traditional HRM practices to advance the hotel’s performance. Additionally, the SEM findings supported an excellent model fit, explaining acceptable variance levels in the endogenous factors (OP, C, and CP). As a result, scholars could use this tested model for further research and in another hospitality context. So far, this is the first study that has been conducted in the green-certified hotels in Egypt to reveal the moderation effect of SE on the relationship between SHRM and hotel business outcomes indicators.

6.2. Practical Implications

There are some managerial contributions drawn from this study. First, hotel managers could benefit from these research suggestions by motivating their employees to better practice the SHRM in order to boost their performance and further enhance their firm success factors. Second, our findings revealed that ES is a channel through which hotels could probably gain positive operational and corporate performance outcomes. With the high level of ES orientation in hotels initiated, a win–win association between SHRM and the hotel business outcomes will be assured. Third, this study sends a message to hotel stakeholders, managers, and owners to invest more effort in practising SHRM to maximise the hotel’s performance. Thus, their reputation and performance will be competitive.

6.3. Limitations and Future Research

Like any research, there are some caveats in this study. First, this study depended on the managers’ perspectives in the green-certified hotels to explore their perceived SHRM practices and related business outcomes. Instead, future research may involve other subjects, such as customers or hotel stockholders. Second, the hotel business outcomes construct was developed based on three leading indicators (OP, C, and CP). However, it would be valuable if this measure were tested and further developed. Third, cross-sectional data were used, so the dynamic nature of the causal effects between the endogenous and exogenous factors was not appropriately perfect. However, the PLS-SEM results confirmed the model correlations and relationships; therefore, a longitudinal study could be imperative. Fourth, we could call for a best SHRM practice model study to fill some missing gaps in our study as there is no consensus regarding which set of SHRM practices would be used. Fifth, our sample included the first category of the green-certified hotels in Egypt, which is concentrated in the cities of El Gouna and Hurghada, so a follow-up study could integrate the remaining cities or use a different sample place and type context. The unique features of this hotel’s category may affect the relationship between SHRM and the potential outcomes. Accordingly, the findings of the current study cannot be generalised to all Egyptian hotels and are subject to the investigated sample. Future research avenues could use multiple methodologies or a mixed methodology rather than questionnaires to gather further data.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, W.S., M.N.E.D., A.A. and K.Z.; Data curation, A.A.; Formal analysis, M.N.E.D. and K.Z.; Funding acquisition, W.S.; Project administration, W.S.; Resources, M.N.E.D. and A.A.; Software, M.N.E.D.; Supervision, W.S. and K.Z.; Validation, K.Z.; Visualization, A.A. and K.Z.; Writing—original draft, W.S.; Writing—review & editing, K.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Annual Funding track by the Deanship of Scientific Research, Vice Presidency for Graduate Studies and Scientific Research, King Faisal University, Saudi Arabia [Project No. AN000632].

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in this study.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the Deanship of Scientific Research, Vice Presidency for Graduate Studies and Scientific Research, King Faisal University, Saudi Arabia for funding this research work.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript, or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Carlisle, S.; Zaki, K.; Ahmed, M.; Dixey, L.; McLoughlin, E. The Imperative to Address Sustainability Skills Gaps in Tourism in Wales. Sustainability 2021, 13, 1161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, P.; Comfort, D. The COVID-19 Crisis and Sustainability in the Hospitality Industry. IJCHM 2020, 32, 3037–3050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Comin, L.C.; Aguiar, C.C.; Sehnem, S.; Yusliza, M.-Y.; Cazella, C.F.; Julkovski, D.J. Sustainable Business Models: A Literature Review. Benchmarking Int. J. 2019, 27, 2028–2047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salama, W.; Abdelsalam, E. Impact of Hotel Guests’ Trends to Recycle Food Waste to Obtain Bioenergy. Sustainability 2021, 13, 3094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bush, J.T. Win-Win-Lose? Sustainable HRM and the Promotion of Unsustainable Employee Outcomes. Hum. Resour. Manag. Rev. 2020, 30, 100676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, J.; Zhang, H. Socially Responsible Human Resource Management and Employee Support for External CSR: Roles of Organizational CSR Climate and Perceived CSR Directed toward Employees. J. Bus. Ethics 2019, 156, 875–888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anlesinya, A.; Susomrith, P. Sustainable Human Resource Management: A Systematic Review of a Developing Field. JGR 2020, 11, 295–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luu, T.T. Socially Responsible Human Resource Practices and Hospitality Employee Outcomes. IJCHM 2021, 33, 757–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kramar, R. Beyond Strategic Human Resource Management: Is Sustainable Human Resource Management the next Approach? Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2014, 25, 1069–1089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richards, J. Putting Employees at the Centre of Sustainable HRM: A Review, Map and Research Agenda. Empl. Relat. 2020, 44, 533–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manzoor, F.; Wei, L.; Bányai, T.; Nurunnabi, M.; Subhan, Q.A. An Examination of Sustainable HRM Practices on Job Performance: An Application of Training as a Moderator. Sustainability 2019, 11, 2263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Shen, J.; Zhu, C. Effects of Socially Responsible Human Resource Management on Employee Organizational Commitment. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2011, 22, 3020–3035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, F.Z.; Zhang, Y.; Yang, H.; Wu, B.T. Sustainable HRM through Improving the Measurement of Employee Work Engagement: Third-Person Rating Method. Sustainability 2020, 12, 7100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yusoff, Y.M.; Nejati, M.; Kee, D.M.H.; Amran, A. Linking Green Human Resource Management Practices to Environmental Performance in Hotel Industry. Glob. Bus. Rev. 2020, 21, 663–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, J.; Law, R.; Wei, J.; Shen, H.; Sun, Y. Hotels’ Self-Positioned Image versus Customers’ Perceived Image: A Case Study of a Boutique Luxury Hotel in Hong Kong. Tour. Rev. 2020, 76, 198–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blau, P.M. Exchange and Power in Social Life; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 1964. [Google Scholar]

- De Souza Meira, J.V.; Hancer, M. Using the Social Exchange Theory to Explore the Employee-Organization Relationship in the Hospitality Industry. IJCHM 2021, 33, 670–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wikhamn, W. Innovation, Sustainable HRM and Customer Satisfaction. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2019, 76, 102–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macke, J.; Genari, D. Systematic Literature Review on Sustainable Human Resource Management. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 208, 806–815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Budhiraja, S.; Yadav, S. Employer Branding and Employee-Emotional Bonding—The CSR Way to Sustainable HRM. In Sustainable Human Resource Management; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2020; pp. 133–149. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, C.; Gollan, P.J.; Wilkinson, A. Implementing Sustainable HRM: The New Challenge of Corporate Sustainability. In Contemporary Developments in Green Human Resource Management Research; Routledge: London, UK, 2018; pp. 135–155. [Google Scholar]

- Ricardo de Souza Freitas, W.R.; Jabbour, C.J.C.; Santos, F.C.A. Continuing the Evolution: Towards Sustainable HRM and Sustainable Organizations. Bus. Strategy Ser. 2011, 12, 226–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, C.-H. Do Green Motives Influence Green Product Innovation? T He Mediating Role of Green Value Co-Creation. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2019, 26, 330–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piwowar-Sulej, K. Core Functions of Sustainable Human Resource Management. A Hybrid Literature Review with the Use of H-Classics Methodology. Sustain. Dev. 2021, 29, 671–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roscoe, S.; Subramanian, N.; Jabbour, C.J.; Chong, T. Green Human Resource Management and the Enablers of Green Organisational Culture: Enhancing a Firm’s Environmental Performance for Sustainable Development. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2019, 28, 737–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaki, K. Implementing Dynamic Revenue Management in Hotels during COVID-19: Value Stream and Wavelet Coherence Perspectives. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2022, 34, 1768–1795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ehnert, I. Sustainable Human Resource Management: A Conceptual and Exploratory Analysis from a Paradox Perspective; Physica-Verlag: Berlin, Germany, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Ehnert, I.; Parsa, S.; Roper, I.; Wagner, M.; Muller-Camen, M. Reporting on Sustainability and HRM: A Comparative Study of Sustainability Reporting Practices by the World’s Largest Companies. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2016, 27, 88–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yong, J.Y.; Yusliza, M.-Y.; Ramayah, T.; Chiappetta Jabbour, C.J.; Sehnem, S.; Mani, V. Pathways towards Sustainability in Manufacturing Organizations: Empirical Evidence on the Role of Green Human Resource Management. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2020, 29, 212–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baum, T. Does the Hospitality Industry Need or Deserve Talent? Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2019, 31, 3823–3837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, V. Talent Management Dimensions and Their Relationship with Retention of Generation-Y Employees in the Hospitality Industry. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2019, 31, 4150–4169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goh, E.; Okumus, F. Avoiding the Hospitality Workforce Bubble: Strategies to Attract and Retain Generation Z Talent in the Hospitality Workforce. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2020, 33, 100603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, G.; Chen, Y.; Jiang, Y.; Paille, P.; Jia, J. Green Human Resource Management Practices: Scale Development and Validity. Asia Pac. J. Hum. Resour. 2018, 56, 31–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dumont, J.; Shen, J.; Deng, X. Effects of Green HRM Practices on Employee Workplace Green Behavior: The Role of Psychological Green Climate and Employee Green Values. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2017, 56, 613–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newman, A.; Miao, Q.; Hofman, P.S.; Zhu, C.J. The Impact of Socially Responsible Human Resource Management on Employees’ Organizational Citizenship Behaviour: The Mediating Role of Organizational Identification. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2016, 27, 440–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, I.K.W.; Wong, J.W.C. Comparing Crisis Management Practices in the Hotel Industry between Initial and Pandemic Stages of COVID-19. IJCHM 2020, 32, 3135–3156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathews, J. Implementing Green Management in Business Organizations. IUP J. Bus. Strategy 2018, 15, 46–62. [Google Scholar]

- Renwick, D.W.; Redman, T.; Maguire, S. Green Human Resource Management: A Review and Research Agenda. Int. J. Manag. Rev. 2013, 15, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zaki, K.G. Using the Mixed Methods Research to Model the Hotel Performance Measurement in Egypt: An Example from a Hotel Chain. J. Glob. Bus. Insights 2019, 4, 18–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haddock-Millar, J.; O’Donohue, W. Green Human Resource Management and Talent Management. In Contemporary Talent Management; Routledge: London, UK, 2021; pp. 315–333. [Google Scholar]

- Zaki, K.; Qoura, O. Profitability in Egyptian Hotels: Business Model and Sustainability Impact. Res. Hosp. Manag. 2019, 9, 89–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Safavi, H.P.; Karatepe, O.M. High-Performance Work Practices and Hotel Employee Outcomes: The Mediating Role of Career Adaptability. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2018, 30, 1112–1133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luu, T.T. Green Human Resource Practices and Organizational Citizenship Behavior for the Environment: The Roles of Collective Green Crafting and Environmentally Specific Servant Leadership. J. Sustain. Tour. 2019, 27, 1167–1196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramus, C.; Steger, U. The Roles of Supervisory Support Behaviors and Environmental Policy in Employee “Ecoinitiatives” at Leading-Edge European Companies. Acad. Manag. J. 2000, 43, 605–626. [Google Scholar]

- Das, A.K.; Biswas, S.R.; Abdul Kader Jilani, M.M.; Uddin, M. Corporate Environmental Strategy and Voluntary Environmental Behavior—Mediating Effect of Psychological Green Climate. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- AlSuwaidi, M.; Eid, R.; Agag, G. Understanding the Link between CSR and Employee Green Behaviour. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2021, 46, 50–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norton, T.A.; Zacher, H.; Parker, S.L.; Ashkanasy, N.M. Bridging the Gap between Green Behavioral Intentions and Employee Green Behavior: The Role of Green Psychological Climate: Employee Green Behavior. J. Organiz. Behav. 2017, 38, 996–1015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almarzooqi, A.H.; Khan, M.; Khalid, K. The Role of Sustainable HRM in Sustaining Positive Organizational Outcomes: An Interactional Framework. IJPPM 2019, 68, 1272–1292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.J.; Mao, Z. Image of All Hotel Scales on Travel Blogs: Its Impact on Customer Loyalty. J. Hosp. Mark. Manag. 2012, 21, 113–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, F.; Dipietro, R.B.; Gerdes, J.H.; Kline, S.; Avant, T. How Hotel Responses to Negative Online Reviews Affect Customers’ Perception of Hotel Image and Behavioral Intent: An Exploratory Investigation. Tour. Rev. Int. 2018, 22, 23–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devereux, L.; Melewar, T.C.; Dinnie, K.; Lange, T. Corporate Identity Orientation and Disorientation: A Complexity Theory Perspective. J. Bus. Res. 2020, 109, 413–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbas, T.M.; Hussien, F.M. The Effects of Green Supply Chain Management Practices on Firm Performance: Empirical Evidence from Restaurants in Egypt. Tour. Hosp. Res. 2021, 21, 358–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EHA Green Hotels in Egypt 2022. Available online: https://www.greenstarhotel.org/gsh-in-numbers/ (accessed on 27 January 2022).

- Ringle, C.M.; Wende, S.; Will, A. Smart PLS (Version 2.0. M3); University of Hamburg: Hamburg, Germany, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Saunders, M.; Lewis, P.; Thornhill, A. Research Methods for Business Students; Pearson: Harlow, UK, 2012; ISBN 978-0-273-75075-8. [Google Scholar]

- Bryman, A.; Bell, E. Business Research Methods, 9th ed.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Zaki, K. The Impact of Human Resources management practices on Employees’ Productivity in the Hotel Industry. PhD Thesis, Cardiff Metropolitan University, Cardiff, UK, Fayoum University, Fayoum, Egypt, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Adams, R.; Jeanrenaud, S.; Bessant, J.; Denyer, D.; Overy, P. Sustainability-Oriented Innovation: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Manag. Rev. 2016, 18, 180–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chanda, U.; Goyal, P. A Bayesian Network Model on the Interlinkage between Socially Responsible HRM, Employee Satisfaction, Employee Commitment and Organizational Performance. J. Manag. Anal. 2020, 7, 105–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaudhary, R. Green Human Resource Management and Employee Green Behavior: An Empirical Analysis. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2020, 27, 630–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Risher, J.J.; Sarstedt, M.; Ringle, C.M. When to Use and How to Report the Results of PLS-SEM. Eur. Bus. Rev. 2019, 31, 2–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henseler, J.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. A New Criterion for Assessing Discriminant Validity in Variance-Based Structural Equation Modeling. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2015, 43, 115–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kline, T. Psychological Testing: A Practical Approach to Design and Evaluation; SAGE: Newcastle Upon Tyne, UK, 2005; ISBN 978-1-4129-0544-2. [Google Scholar]

- Franke, G.; Sarstedt, M. Heuristics versus Statistics in Discriminant Validity Testing: A Comparison of Four Procedures. Internet Res. 2019, 29, 430–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shmueli, G.; Sarstedt, M.; Hair, J.F.; Cheah, J.-H.; Ting, H.; Vaithilingam, S.; Ringle, C.M. Predictive Model Assessment in PLS-SEM: Guidelines for Using PLSpredict. Eur. J. Mark. 2019, 53, 2322–2347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sobaih, A.E.E. Human Resource Management in Hospitality Firms in Egypt: Does Size Matter? Tour. Hosp. Res. 2018, 18, 38–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kock, N. Common Method Bias in PLS-SEM: A Full Collinearity Assessment Approach. Int. J. E-Collab. 2015, 11, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hair, J.F., Jr.; Hult, G.T.M.; Ringle, C.; Sarstedt, M. A Primer on Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM); Sage Publications: Newcastle Upon Tyne, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Chin, W.W.; Marcolin, B.L.; Newsted, P.R. A Partial Least Squares Latent Variable Modeling Approach for Measuring Interaction Effects: Results from a Monte Carlo Simulation Study and an Electronic-Mail Emotion/Adoption Study. Inf. Syst. Res. 2003, 14, 189–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Úbeda-García, M.; Marco-Lajara, B.; Zaragoza-Sáez, P.C.; Manresa-Marhuenda, E.; Poveda-Pareja, E. Green Ambidexterity and Environmental Performance: The Role of Green Human Resources. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2022, 29, 32–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Romeedy, B.S. Green Human Resource Management in Egyptian Travel Agencies: Constraints of Implementation and Requirements for Success. J. Hum. Resour. Hosp. Tour. 2019, 18, 529–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaudhary, R. Effects of Green Human Resource Management: Testing a Moderated Mediation Model. IJPPM 2019, 70, 201–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nisar, Q.A.; Haider, S.; Ali, F.; Naz, S.; Ryu, K. Depletion of Psychological, Financial, and Social Resources in the Hospitality Sector during the Pandemic. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2021, 93, 102794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).