Sustainability of Cultural Memory: Youth Perspectives on Yugoslav World War Two Memorials

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Contested Memorial Heritage of SFR Yugoslavia

3. Materials and Methods

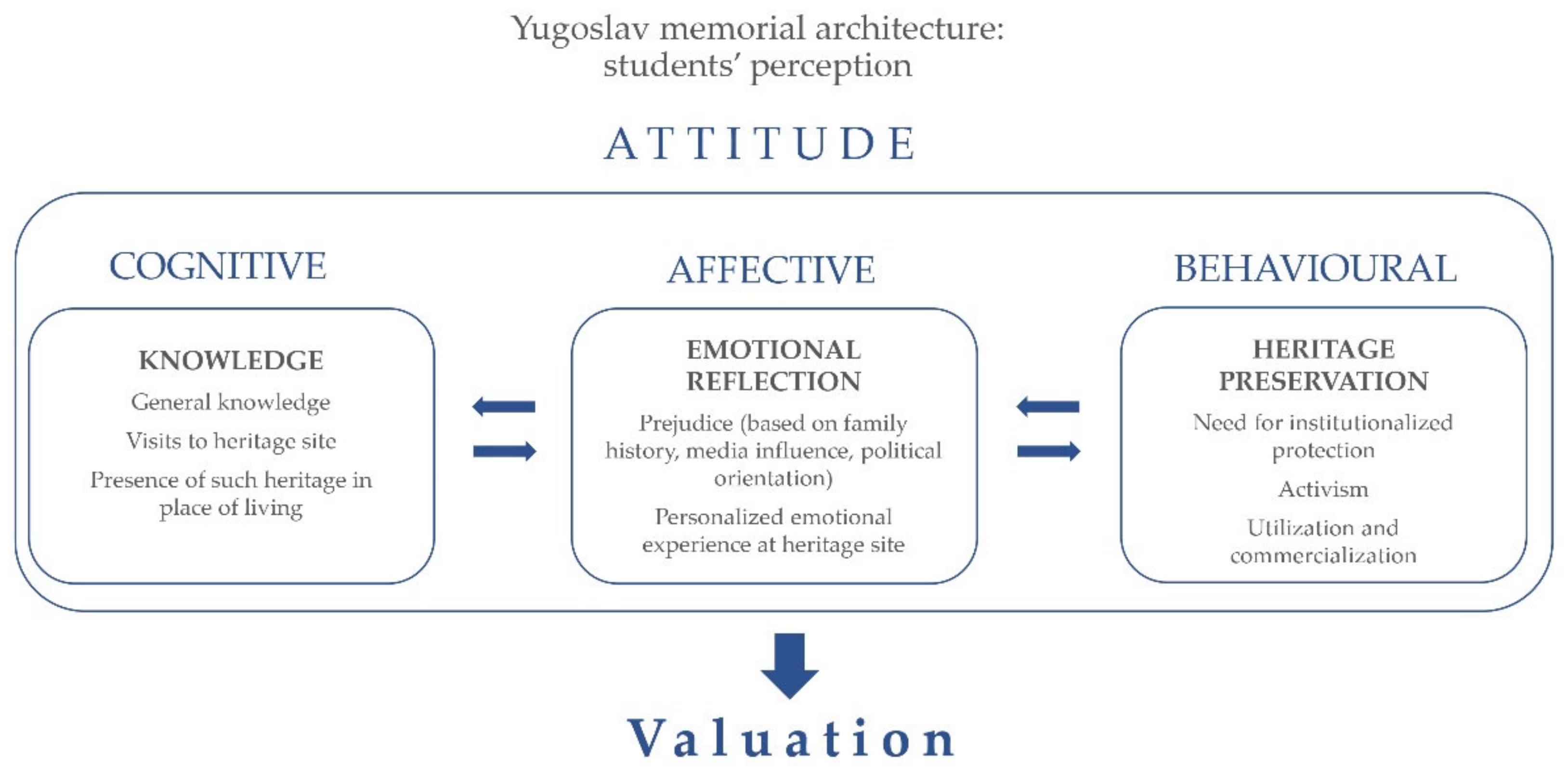

4. Results and Discussion

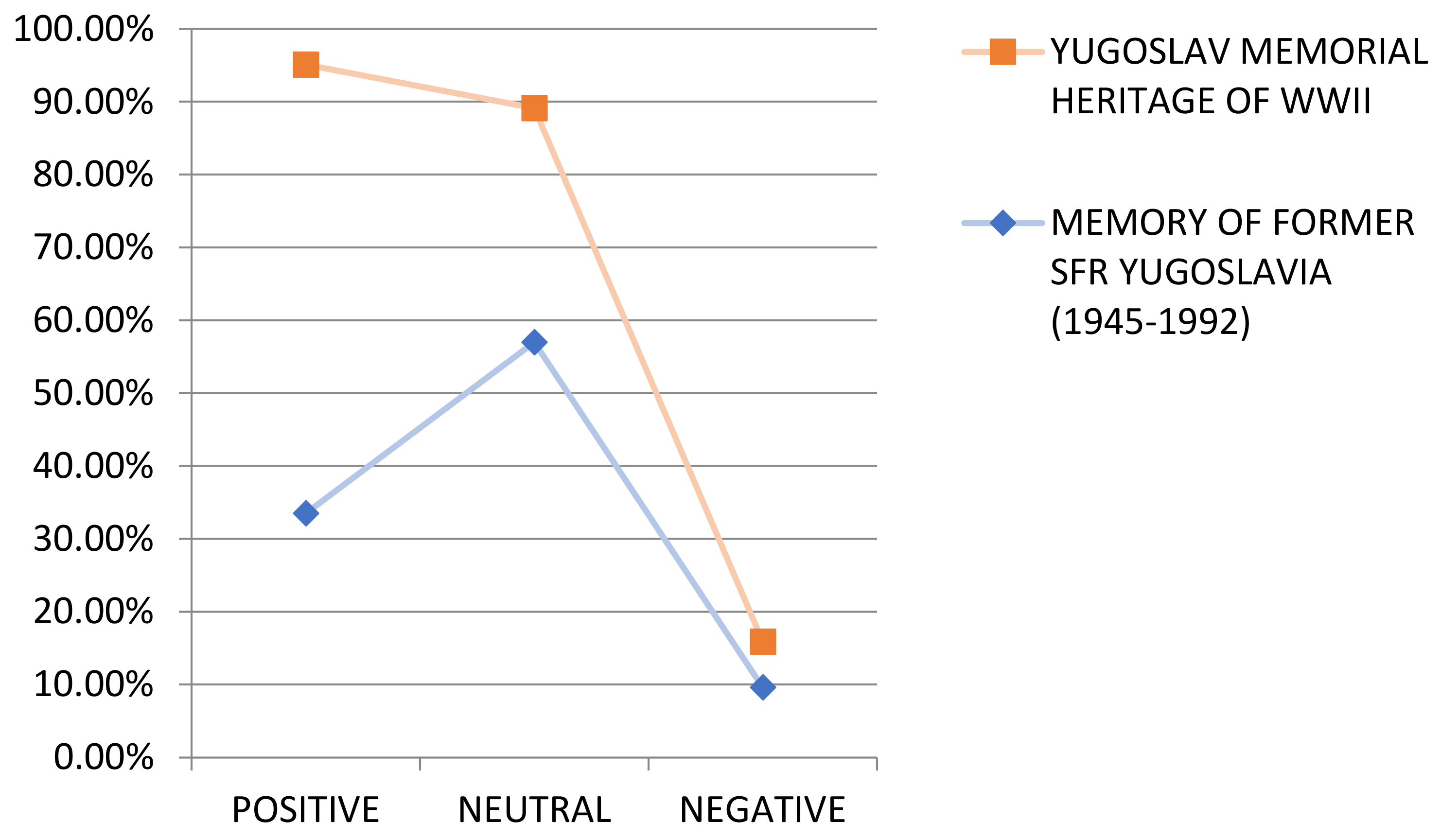

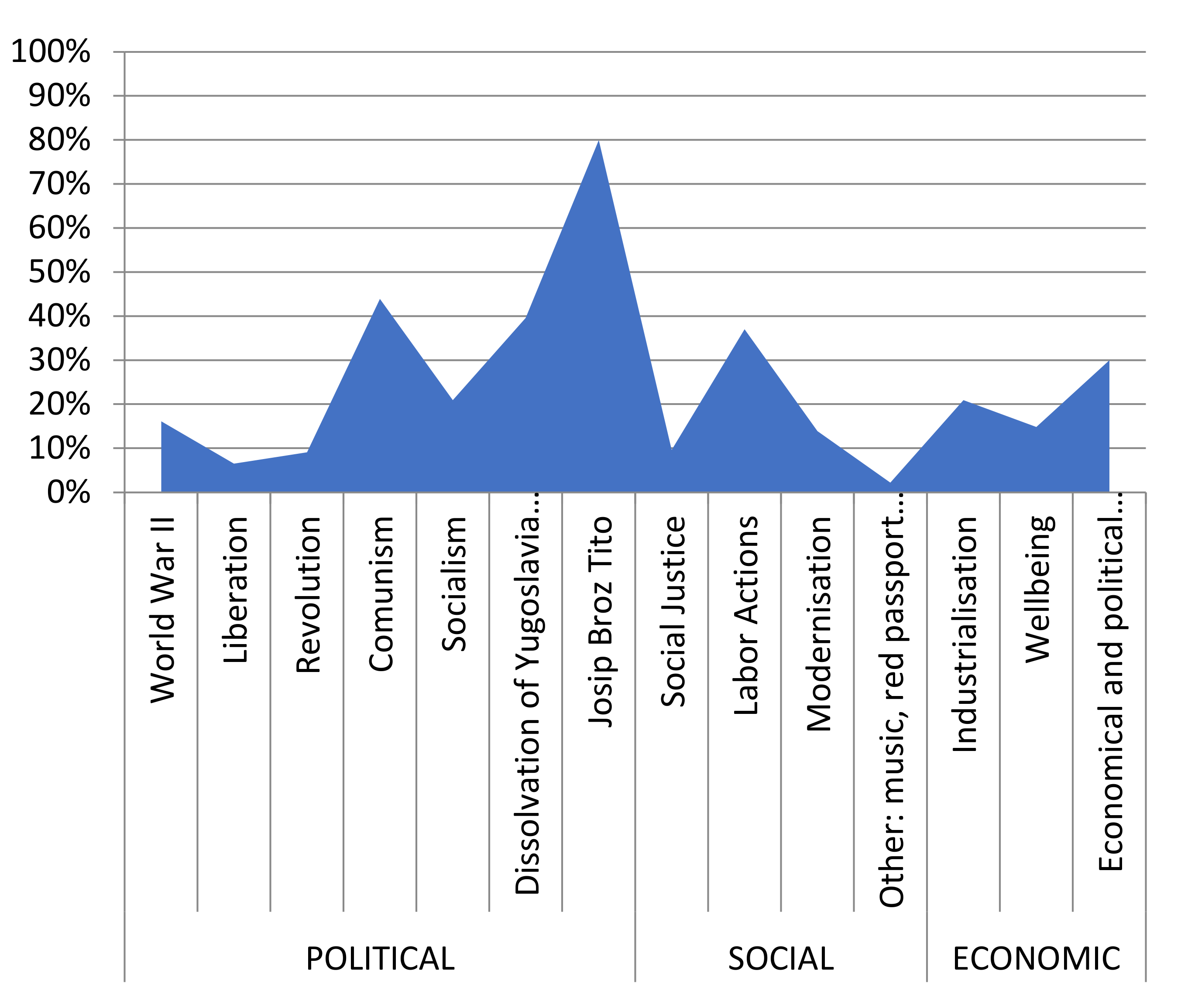

4.1. Measuring Emotional Reflections of Yugoslav History and Heritage

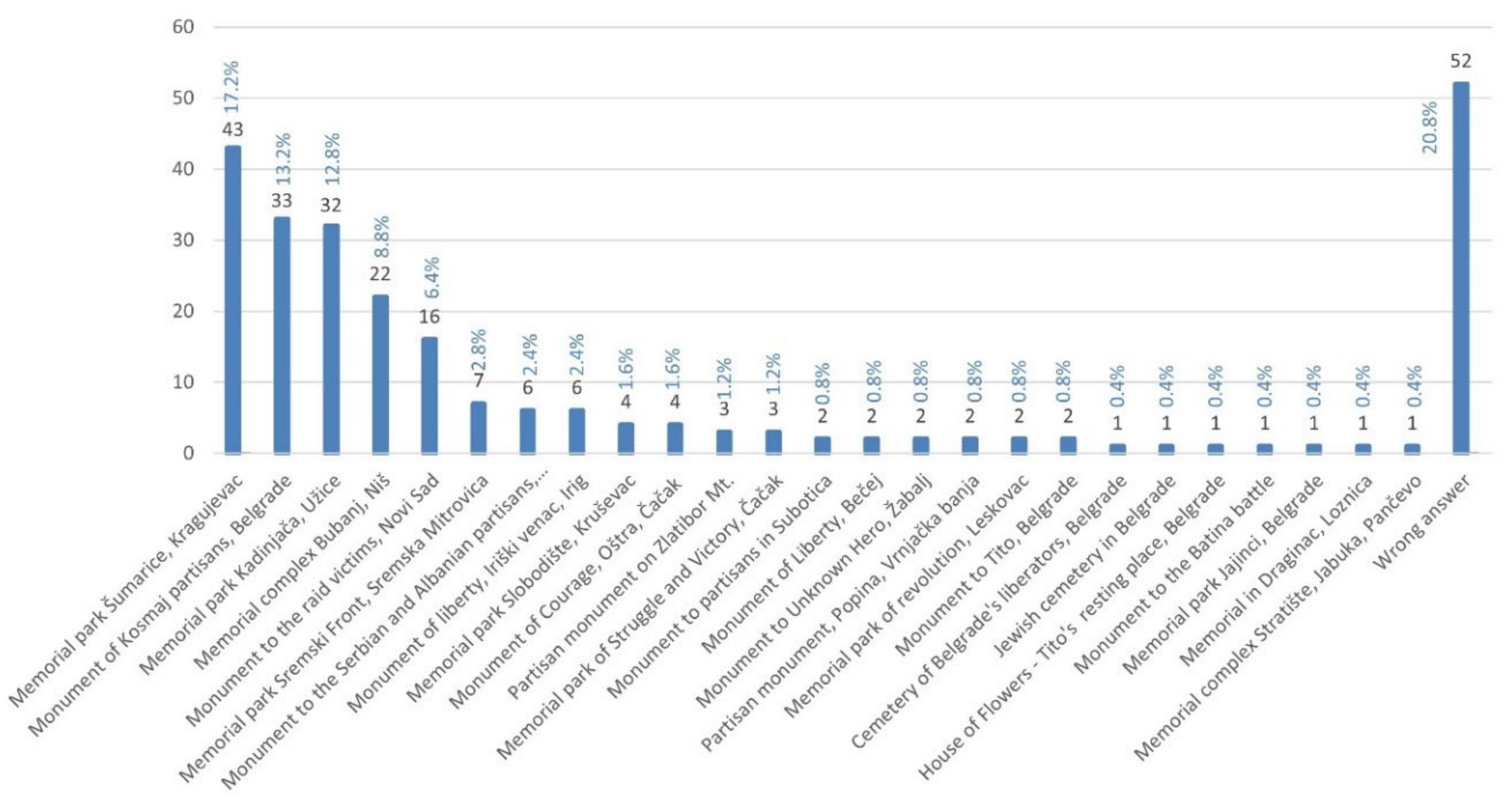

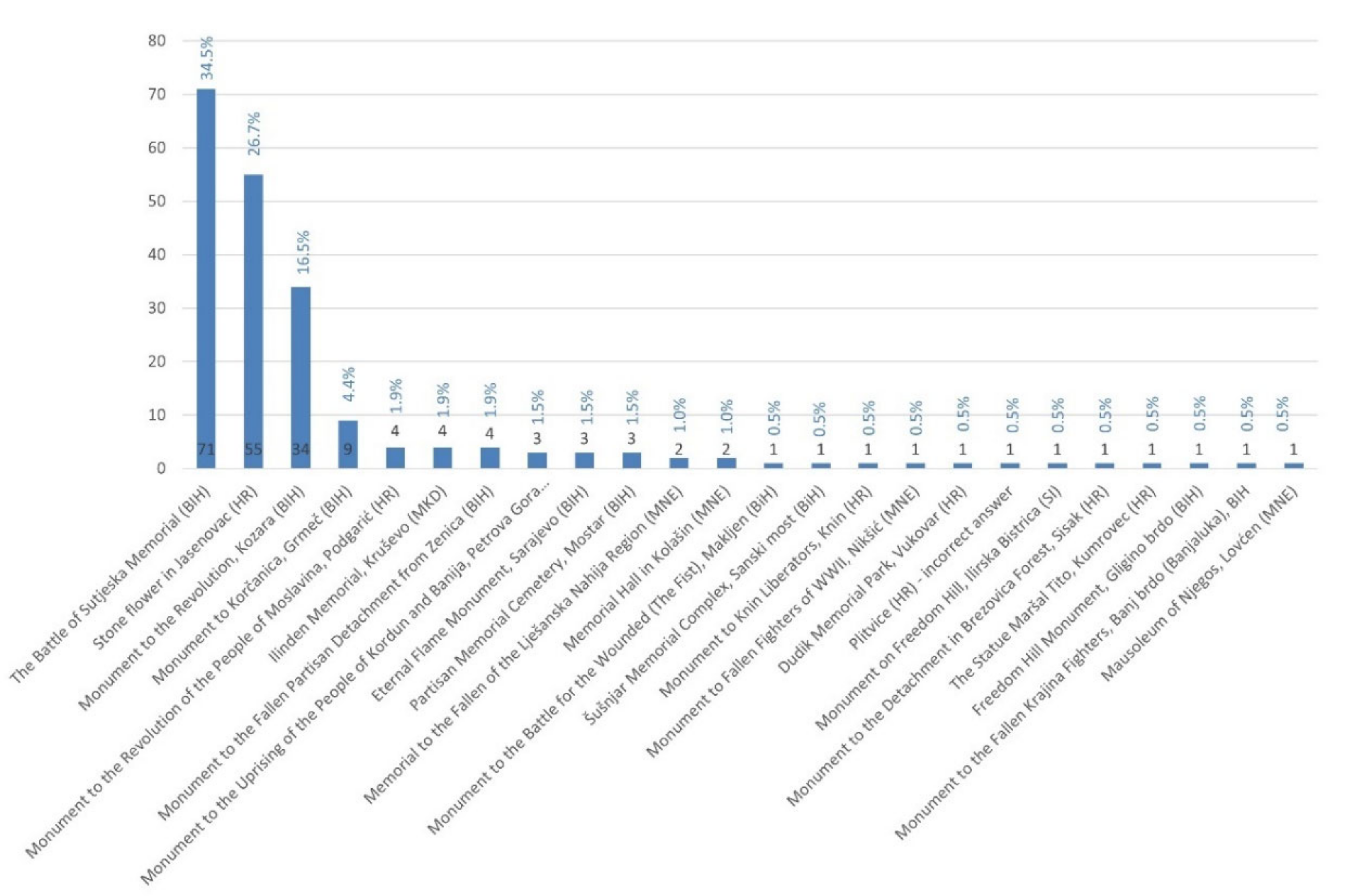

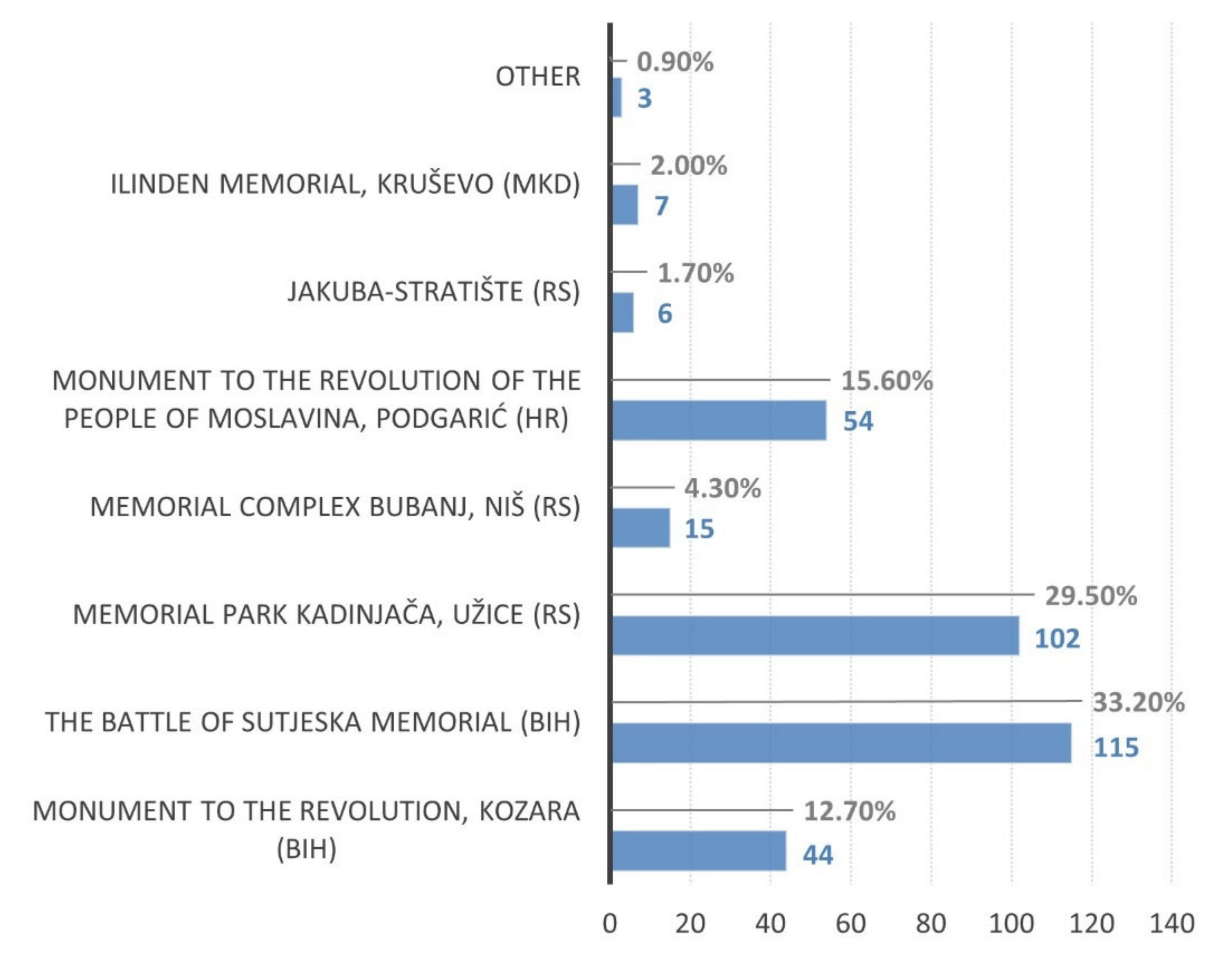

4.2. Estimating Knowledge Levels

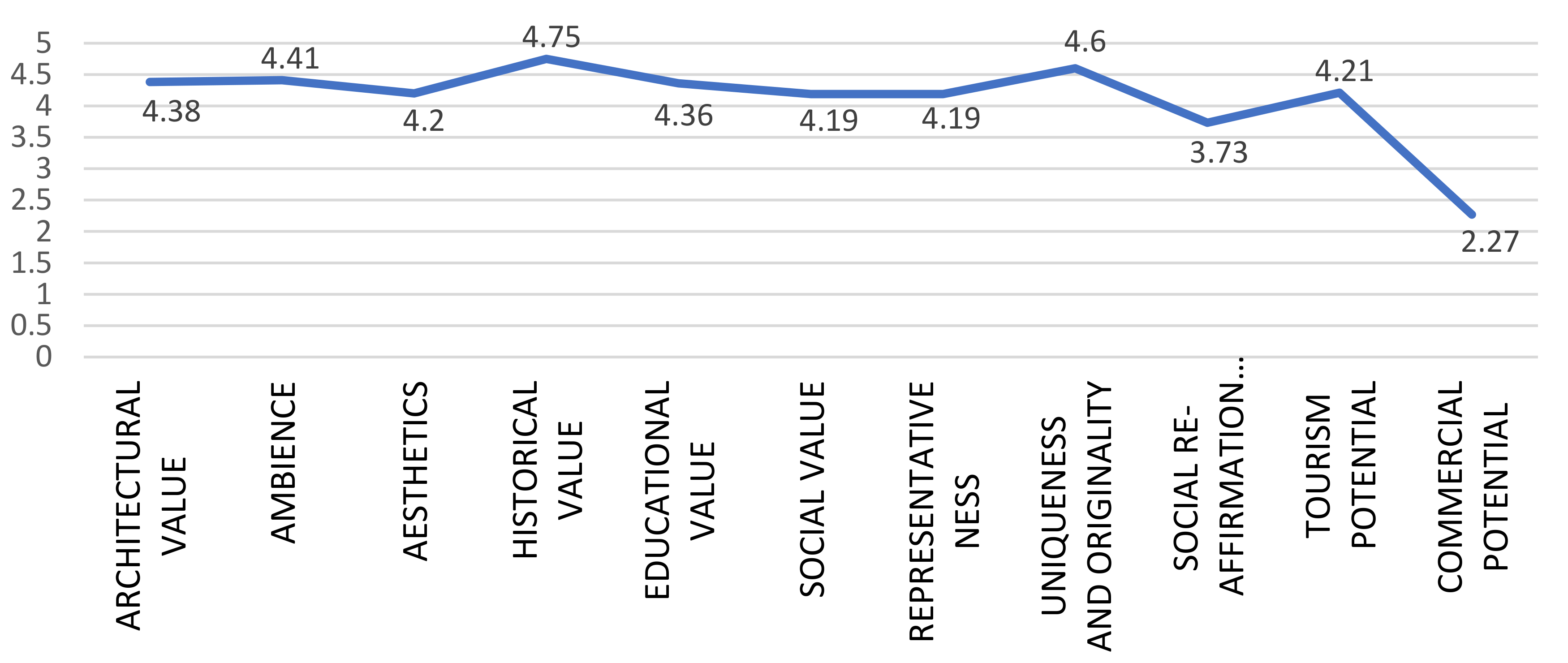

4.3. Valuation

4.4. Thoughts on Preservation

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Alhaddi, H. Triple bottom line and sustainability: A literature review. Bus. Manag. Stud. 2015, 1, 6–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKenzie, S. Social Sustainability: Towards Some Definitions; Hawke Research Institute, University of South Australia: Magill, Australia, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Stren, R.; Polèse, M. 1 Understanding the new sociocultural dynamics of cities: Comparative urban policy in a global context. In The Social Sustainability of Cities: Diversity and the Management of Change; Polese, M., Stren, R., Eds.; University of Toronto Press: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2017; pp. 1–38. [Google Scholar]

- Hussein, F.; Stephens, J.; Tiwari, R. Cultural memories for better place experience: The case of Orabi square in Alexandria, Egypt. Urban Sci. 2020, 4, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assmann, J.; Czaplicka, J. Collective memory and cultural identity. New Ger. Crit. 1995, 65, 125–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assmann, J. Communicative and cultural memory. In Cultural Memories: The Geographical Point of View; Meusburger, P., Heffernan, M., Wunder, E., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2011; pp. 15–27. [Google Scholar]

- Assmann, A. Cultural memory. In Social Trauma—An Interdisciplinary Textbook; Hamburger, A., Hancheva, C., Volkan, V.D., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2021; pp. 25–37. [Google Scholar]

- King, L.; Stark, J.F.; Cooke, P. Experiencing the digital world: The cultural value of digital engagement with heritage. Herit. Soc. 2016, 9, 76–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashworth, G.J.; Graham, B. Senses of Place: Senses of Time, 1st ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Silberman, N. Chasing the unicorn? The quest for “essence” in digital heritage. In New Heritage: New Media and Cultural Heritage; Kalay, Y., Kvan, T., Affleck, J., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2008; pp. 81–91. [Google Scholar]

- Samuel, R. Theatres of Memory: Past and Present in Contemporary Culture; Verso: London, UK, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Nora, P. Between memory and history: Les lieux de mémoire. Representations 1989, 26, 7–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kenny, M.G. A Place for memory: The interface between individual and collective history. Comp. Stud. Soc. Hist. 1999, 41, 420–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crinson, M. Urban Memory: History and Amnesia in the Modern City, 1st ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Ringas, D.; Christopoulou, E.; Stefanidakis, M. Urban memory in space and time. In Handbook of Research on Technologies and Cultural Heritage: Applications and Environments; Styliaras, G., Koukopoulos, D., Lazarinis, F., Eds.; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2011; pp. 325–340. [Google Scholar]

- Copernicus Service in Support to EU External Action. Available online: https://sea.security.copernicus.eu/domains/cultural-heritage (accessed on 15 February 2022).

- Council of Europe. Convention for the Protection of the Architectural Heritage of Europe (ETS No. 121); Council of Europe: Strasbourg, France, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Graham, B. Heritage as knowledge: Capital or culture? Urban Stud. 2002, 39, 1003–1017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashworth, G.J. Heritage and economic development: Selling the unsellable. Herit. Soc. 2014, 7, 3–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrison, R. Heritage: Critical Approaches, 1st ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Loulanski, T. Revising the concept for cultural heritage: The argument for a functional approach. Int. J. Cult. Prop. 2006, 13, 207–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Dupre, K.; Jin, X. A systematic review of literature on contested heritage. Curr. Issues Tour. 2021, 24, 442–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graham, B.; Howard, P. The Ashgate Research Companion to Heritage and Identity; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Timothy, D.J.; Nyapane, G.P. Cultural Heritage and Tourism in the Developing World: A Regional Perspective, 1st ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Harrison, R.; DeSilvey, C.; Holtorf, C.; Macdonald, S.; Bartolini, N.; Breithoff, E.; Fredheim, H.; Lyons, A.; May, S.; Morgan, J.; et al. Heritage Futures: Comparative Approaches to Natural and Cultural Heritage Practices; UCL Press: London, UK, 2020; pp. 20–50. [Google Scholar]

- Hrobat Virloget, K.; Čebron Lipovec, N. Heroes we love? Monuments to the National liberation movement in Istria between memories, care, and collective silence. Stud. Ethnol. Croat. 2017, 29, 45–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Cremaschi, M. Place is memory: A framework for placemaking in the case of the human rights memorials in Buenos Aires. City Cult. Soc. 2021, 27, 100419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Candau, J. Anthropologie de le Mémoire; Armand Colin: Paris, France, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Eco, U. Vegetal and Mineral Memory: The Future of Books. Available online: https://www.bibalex.org/attachments/english/Vegetal_and_Mineral_Memory.pdf (accessed on 23 December 2021).

- Stevanović, N. Architectural Heritage of Yugoslav-Socialist Character: Ideology, Memory and Identity. Ph.D. Thesis, Polytechnic University of Catalonia, Barcelona, Spain, 7 September 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Macdonald, S. Memorylands: Heritage and Identity in Europe Today, 1st ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Horvatinčić, S. The peculiar case of spomeniks. Monumental commemorative sculpture in former Yugoslavia between invisibility and popularity. In Proceedings of the II Lisbon Summer School for the Study of Culture—Peripheral Modernities, Lisbon, Portugal, 9–14 July 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Horvatinčić, S. Monument, territory, and the mediation of war memory in socialist Yugoslavia. Život Umjet. 2015, 96, 32–59. [Google Scholar]

- Hrženjak, J. Demolition of the Anti-Fascist Monuments in Croatia 1990–2000; Savez Antifašističkih Boraca Hrvatske: Zagreb, Croatia, 2001. (In Croatian) [Google Scholar]

- Stierli, M.; Kulić, V. Toward a Concrete Utopia: Architecture in Yugoslavia, 1948–1980; Museum of Modern Art: New York, NY, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Jauković, M. To share or to keep: The afterlife of Yugoslavia’s heritage and the contemporary heritage management practices. Croat. Political. Sci. Rev. 2014, 51, 80–104. [Google Scholar]

- Putnik, V. Second World War monuments in Yugoslavia as witnesses of the past and the future. J. Tour. Cult. Chang. 2016, 14, 206–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konstantinović, D.; Jović, S. Novi Sad Modern City: Researching, evaluating and curating the unabsorbed modernization of the city. Zb. Muz. Primenj. Umet. 2021, 17, 23–32. (In Serbian) [Google Scholar]

- Zeković, M.; Žugić, V.; Stojković, B. Intangible, fetishized & constructed—New contexts for staging the socialist heritage. In Three Decades of Post-Socialist Transition; Čamprag, N., Suri, A., Eds.; TUPRINTS Darmstadt: Darmstadt, Germany, 2019; pp. 51–59. [Google Scholar]

- Palmberger, M. How Generations Remember. Conflicting Histories and Shared Memories in Post-War Bosnia and Herzegovina; The Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Combi, C. Generation Z: Their Voices, Their Lives; Hutchinson: London, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Prensky, M. Digital natives, digital immigrants. Horizon 2001, 9, 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Monaci, S.; Tirocchi, S. Eternal present of the spotless mind—Youth, memory and participatory media. In Proceedings of the ESA Research Network Sociology of Culture Midterm Conference: Culture and the Making of Worlds, Milan, Italy, 15 October 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Halbwachs, M. On Collective Memory; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Kisić, V. Governing Heritage Dissonance: Promises and Realities of Selected Cultural Policies; European Cultural Foundation: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, J.; Gibson, L.K. Digitisation, digital interaction and social media: Embedded barriers to democratic heritage. Int. J. Herit. Stud. 2017, 23, 408–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foot, K.; Warnick, B.; Schneider, M. Web-based memorializing after September 11: Toward a conceptual framework. J. Comput. Mediat. Commun. 2006, 11, 72–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silvestri, L.E. Start where you are: Building cairns of collaborative memory. Mem. Stud. 2021, 14, 275–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burkey, B. Total recall: How cultural heritage communities use digital initiatives and platforms for collective remembering. J. Creat. Commun. 2019, 14, 235–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khlevnyuk, D. Narrowcasting collective memory online: ‘Liking’ Stalin in Russian social media. Media Cult. Soc. 2019, 41, 317–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reading, A. Seeing red: A political economy of digital memory. Media Cult. Soc. 2014, 36, 748–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenberg, M.J.; Hovland, C.I.; McGuire, W.J.; Abelson, R.P.; Brehm, J.W. Attitude Organization and Change: An Analysis of Consistency among Attitude Components; Yale University Press: New Haven, CT, USA, 1960. [Google Scholar]

- Park, H.Y. Heritage tourism. Ann. Tour. Res. 2010, 37, 116–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uzzell, D.; Ballantyne, R. Heritage that hurts: Interpretation in a postmodern world. In Contemporary Issues in Heritage and Environmental Interpretation; Uzzell, D., Ballantyne, R., Eds.; Stationery Office: London, UK, 1998; pp. 152–171. [Google Scholar]

- Fiket, A. Opportunities for Tourism Valorisation of Monuments from the Period of Socialism in Croatia. Master’s Thesis, University of Zagreb, Zagreb, Croatia, 24 September 2020. (In Croatian). [Google Scholar]

- Kadić, S. The World War II in the political discourse of the modern Croatia. Stephanos 2016, 3, 11–18. [Google Scholar]

- Šulc, B. Development of Museums in Yugoslavia. Inform. Museol. 1984, 15, 3–7. (In Croatian) [Google Scholar]

- Kalay, Y.E. Preserving cultural heritage through digital media. In New Heritage; Kalay, Y.E., Kvan, T., Affleck, J., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2008; pp. 17–26. [Google Scholar]

- Maniou, T.A. Semantic analysis of cultural heritage news propagation in social media: Assessing the role of media and journalists in the era of big data. Sustainability 2021, 13, 341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peinado-Santana, S.; Hernández-Lamas, P.; Bernabéu-Larena, J.; Cabau-Anchuelo, B.; Martín-Caro, J.A. Public works heritage 3D model digitisation, optimisation and dissemination with free and open-source software and platforms and low-cost tools. Sustainability 2021, 13, 13020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tešić, M.; Dimitrijević, B. How Yugoslav Memorial Sites Became a Global Hit and Why that is a Problem. Available online: https://www.vice.com/sr/article/8xbkpz/kako-su-jugoslovenski-spomenici-postali-svetski-hit-i-zasto-je-to-problem (accessed on 28 December 2021).

- Horvatinčić, S. Between memory politics and new models of heritage management: Rebuilding Yugoslav memorial sites ‘from below’. ICOMOS–Hefte Des. Dtsch. Natl. 2020, 73, 108–115. [Google Scholar]

- Du Cros, H. A new model to assist in planning for sustainable cultural heritage tourism. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2001, 3, 165–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanojlović, A.; Ćurčić, N.; Pavlović, N. Tourism valorisation of site “Lazar’s town” in Kruševac. J. Geogr. Inst. Jovan Cvijic SASA 2010, 60, 77–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jakir, A. “Monuments are the past and the future”. Political and administrative mechanisms of financing monuments during socialist Yugoslavia. Cas. Suvrem. Povij. 2019, 51, 151–182. (In Croatian) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musa, S.; Kranjcevic, J.; Šakić, D. Do memorial sites from the Second World War possess potential for tourism development–examples from Croatia and Bosnia and Herzegovina. In Proceedings of the ITHMC International Tourism and Hospitality Management Conference, Sarajevo, Bosnia and Herzegovina, 30 September–4 October 2015; pp. 130–141. [Google Scholar]

- Janev, G. Burdensome past: Challenging the socialist heritage in Macedonia. Studia Ethnol. Croat. 2017, 29, 149–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roter-Blagojević, M.; Nikolić, M.; Vukotić-Lazar, M. Serbia—Report. In Heritage at Risk: World Report 2014–2015 on Monuments and Sites in Danger; Machat, C., Ziesemer, J., Eds.; Hendrik Bäßler Verlag: Berlin, Germany, 2017; pp. 125–128. [Google Scholar]

- Guglielmucci, A.; Scaraffuni Ribeiro, L. Site of memory and site of forgetting: The repurposing of the Punta carretas prison. Lat. Am. Perspect. 2016, 43, 131–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lobovikov-Katz, A. Heritage education for heritage conservation—A teaching approach (contribution of educational codes to study of deterioration of natural building stone in historic monuments). Strain 2009, 45, 480–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lobovikov-Katz, A.; Martins, J.; Ioannides, M.; Sojref, D.; Degrigny, C. Interdisciplinarity of cultural heritage conservation making and makers: Through diversity towards compatibility of approaches. In Proceedings of the EuroMed 2018: Digital Heritage. Progress in Cultural Heritage: Documentation, Preservation, and Protection—7th International Conference, Nicosia, Cyprus, 29 October–3 November 2018; pp. 623–638. [Google Scholar]

- Grmuša, M.; Šušnjar, S.; Lukić Tanović, M. The attitudes of the local population toward the importance of cultural and historical heritage. J. Geogr. Inst. Jovan Cvijic SASA 2020, 70, 299–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Total | Number of Valid Respondents | Valid Percent | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 230 | 100% | ||

| Country/region of origin | Bosnia and Herzegovina | 18 | 7.8% |

| Montenegro | 5 | 2.2% | |

| Croatia | 1 | 0.4% | |

| Serbia | 206 | 89.6% | |

| Vojvodina region | 144 | 62.6% | |

| Belgrade region | 7 | 3.0% | |

| Šumadija and Western Serbia | 41 | 17.8% | |

| Southern and Eastern Serbia | 14 | 6.1% | |

| Gender | Male | 75 | 32,6% |

| Female | 155 | 67.4% | |

| Age group | Up to 25 years | 219 | 95.2% |

| 26–40 | 11 | 4.8% | |

| Over 40 years | 0 | 0% |

| Sum of Squares | df | Mean Square | F | Sig. | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Emotions towards the SFRY × Students’ region of origin | Between groups (combined) | 13.302 | 8 | 1.663 | 2.413 | 0.016 |

| Within groups | 152.992 | 222 | 0.689 | |||

| Total | 166.294 | 230 | ||||

| Emotions towards memorials of WWII × Students’ region of origin | Between groups (combined) | 28.911 | 8 | 3.614 | 2.584 | 0.010 |

| Within groups | 310.448 | 222 | 1.398 | |||

| Total | 339.359 | 230 |

| Knowledge Levels N = 230 | Visual Recognition of Memorials | Visits to Memorials | Positive Interest in Memorials | Recognition of Educational and Promotional Needs | Awareness of Heritage Protection Needs |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| no | 10.30% | 11.60% | 0.40% | 4.80% | 4.8% (well-protected) |

| do not know | 15% | 30.50% | 6.90% | 14.60% | 20.2% (modest protection) |

| probably yes | 19.30% | 24.3% | 31.30% | - | 56.1% (insufficient protection) |

| yes | 54.50% | 57.4% | 60.50% | 79.80% | 16.9% (neglected) |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Radulović, V.; Terzić, A.; Konstantinović, D.; Zeković, M.; Peško, I. Sustainability of Cultural Memory: Youth Perspectives on Yugoslav World War Two Memorials. Sustainability 2022, 14, 5586. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14095586

Radulović V, Terzić A, Konstantinović D, Zeković M, Peško I. Sustainability of Cultural Memory: Youth Perspectives on Yugoslav World War Two Memorials. Sustainability. 2022; 14(9):5586. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14095586

Chicago/Turabian StyleRadulović, Veljko, Aleksandra Terzić, Dragana Konstantinović, Miljana Zeković, and Igor Peško. 2022. "Sustainability of Cultural Memory: Youth Perspectives on Yugoslav World War Two Memorials" Sustainability 14, no. 9: 5586. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14095586

APA StyleRadulović, V., Terzić, A., Konstantinović, D., Zeković, M., & Peško, I. (2022). Sustainability of Cultural Memory: Youth Perspectives on Yugoslav World War Two Memorials. Sustainability, 14(9), 5586. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14095586