Developing Resilience to Disinformation: A Game-Based Method for Future Communicators

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. Background and Importance

1.2. Study Aims

2. Literature Review

2.1. Research on Fake News and Media Literacy

2.2. Game-Based Learning

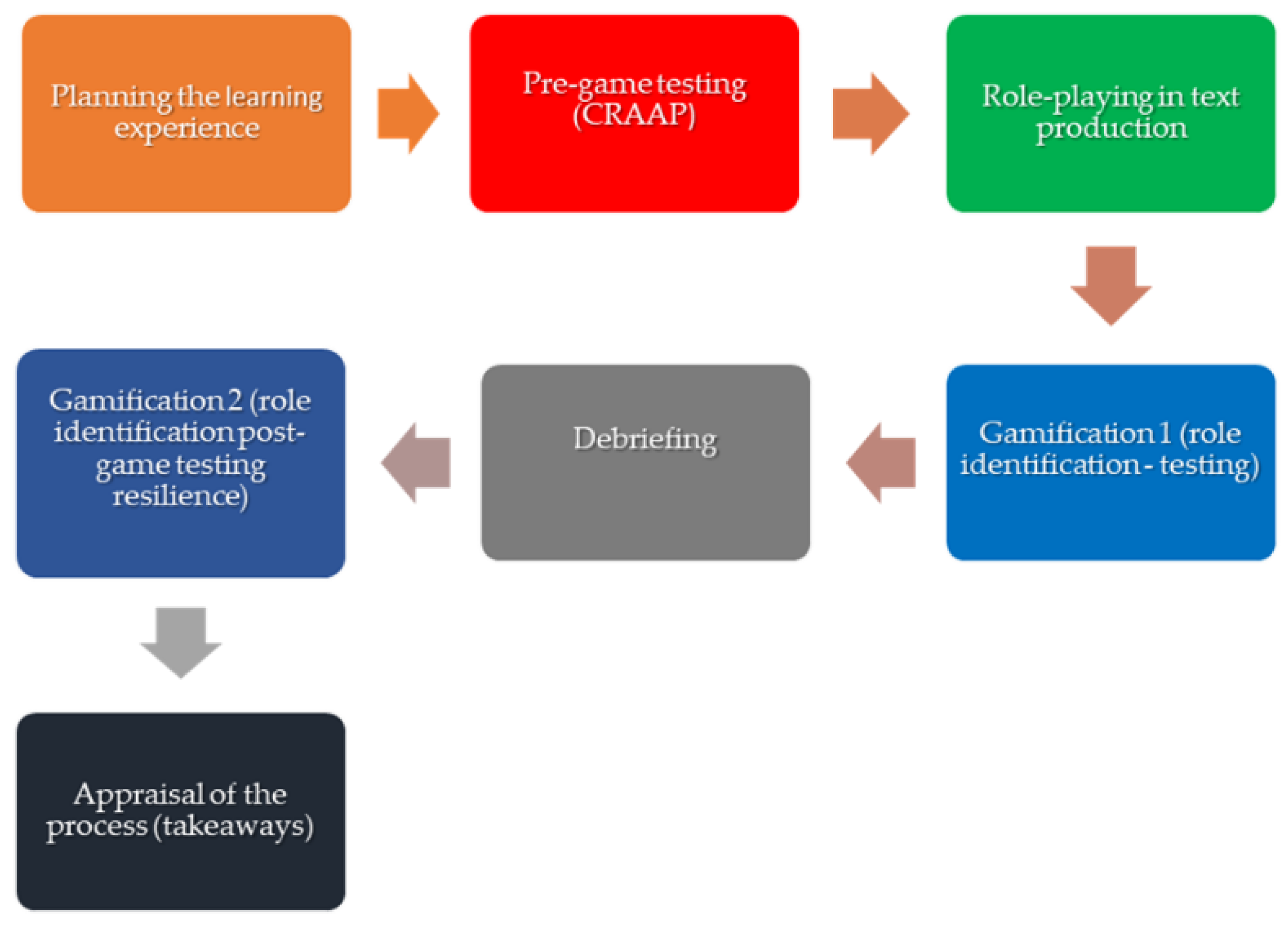

3. Design and Methods

4. Game Playing and Results

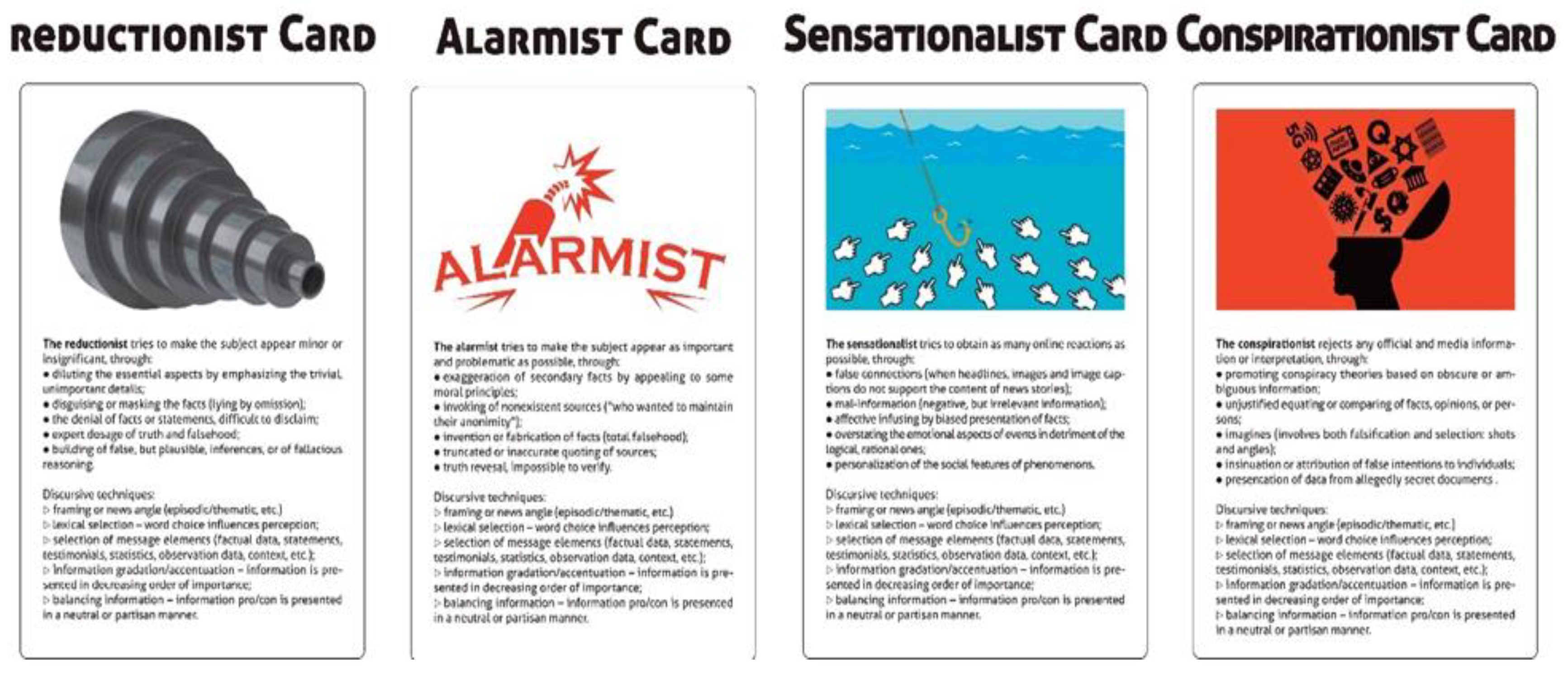

- Title of the article;

- Lexical choices (selection of words by which articles induce a state of alert or, on the contrary, try to “anesthetize” the audience);

- Data manipulation—by exaggeration, falsification, (in)existing connections;

- Ambiguity in expressions.

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- The Grünwald Declaration on Media Education. Educ. Media Int. 1983, 20, 26. [CrossRef]

- UNESCO. Seoul Declaration on Media and Information Literacy for Everyone and by Everyone. 2020. Available online: https://en.unesco.org/news/seoul-declaration-media-and-information-literacy-everyone-and-everyone-0 (accessed on 12 December 2021).

- European Commission. Media Literacy Expert Group (E02541). 2011. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/transparency/expert-groups-register/screen/expert-groups/consult?do=groupDetail.groupDetail&groupID=2541 (accessed on 21 December 2021).

- Purian, R.; Ho, S.M.; Dov, T. Resilience of society to recognize disinformation: Human and/or machine intelligence. In Proceedings of the UK Academy for Information Systems Conference Proceedings, Virtual, 29 April 2020; Available online: https://aisel.aisnet.org/ukais2020/11 (accessed on 20 December 2021).

- Zarocostas, J. How to fight an infodemic. Lancet 2020, 395, 676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Available online: https://stirioficiale.ro/informatii (accessed on 21 December 2021).

- Krawczyk, K.; Chelkowski, T.; Laydon, D.J.; Mishra, S.; Xifara, D.; Gibert, B.; Flaxman, S.; Mellan, T.; Schwämmle, V.; Röttger, R.; et al. Quantifying Online News Media Coverage of the COVID-19 Pandemic: Text Mining Study and Resource. J. Med. Internet Res. 2021, 23, e28253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gherheș, V.; Stoian, C.; Fărcașiu, M.; Stanici, M. E-Learning vs. Face-To-Face Learning: Analyzing Students’ Preferences and Behaviors. Sustainability 2021, 13, 4381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. Proposal for a COUNCIL RECOMMENDATION on Key Competences for LifeLong Learning. 2018. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:52018SC0014&from=EN (accessed on 21 December 2021).

- Wardle, C.; Derakhshan, H. Information Disorder: Toward an Interdisciplinary Framework for Research and Policymaking; Council of Europe CEDEX: Strasbourg, France, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Farmer, L.S.J. Fake News in Context; Routledge: London, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- LaGarde, J.; Hudgins, D. Fact vs. Fiction: Teaching Critical Thinking Skills in the Age of Fake News; International Society for Technology in Education: Portland, Oregon; Arlington, VA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- McDougal, J. Fake News vs Media Studies: Travels in a False Binary; Palgrave Macmillan: Cham, Switzerland, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Silverblatt, A.; Smith, A.; Miller, D.; Smith, J.; Brown, N. Media Literacy: Keys to Interpreting Media Messages; Praeger: Santa Barbara, CA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Potter, J.W. Media Literacy, 9th ed.; SAGE Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Janke, R.W.; Cooper, B.S. News Literacy: Helping Students and Teachers Decode Fake News; Rowman & Littlefield: Lanham, MD, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Fleming, J.; Karadjov, C. Focusing on Facts. Media and News Literacy Education in the Age of Misinformation. In Media Literacy in a Disruptive Media Environment; Christ, W.G., De Abreu, B.S., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2020; pp. 77–93. [Google Scholar]

- Berman, J.; Graham, L. Learning Intervention: Educational Casework and Responsive Teaching for Sustainable Learning; Routledge: London, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Starosielski, N.; Walker, J. (Eds.) Sustainable Media: Critical Approaches to Media and Environment; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Kellner, D.; Share, J. The Critical Media Literacy Guide: Engaging Media and Transforming Education; Brill Sense: Leiden, The Netherlands, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Karmasin, M.; Voci, D. The role of sustainability in media and communication studies’ curricula throughout Europe. Int. J. Sustain. High. Educ. 2021, 22, 42–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jenkins, H. Confronting the Challenges of Participatory Culture. Media Education for the 21st Century; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gillin, J.L.; Huizinga, J. Homo Ludens: A Study of the Play-Element in Culture; Beacon Press: Boston, MA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Naegele, K.D.; Goffman, E. The Presentation of Self in Everyday Life; Anchor Books: New York, NY, USA, 1959. [Google Scholar]

- Dichev, C.; Dicheva, D. Gamifying education: What is known, what is believed and what remains uncertain: A critical review. Int. J. Educ. Technol. High. Educ. 2017, 14, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Qian, M.; Clark, K.R. Game-based Learning and 21st century skills: A review of recent research. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2016, 63, 50–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mystakidis, S.; Filippousis, G.; Tolis, D.; Tseregkouni, E. Playful Metaphors for Narrative-Driven E-Learning. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 11682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowman, S.L. The Functions of Role-Playing Games: How Participants Create Community, Solve Problems and Explore Identity; McFarland: Jefferson, CA, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Roozenbeek, J.; van der Linden, S. The fake news game: Actively inoculating against the risk of misinformation. J. Risk Res. 2018, 22, 570–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caperton, I.H. Toward a Theory of Game-Media Literacy: Playing and Building as Reading and Writing. Int. J. Gaming Comput. Mediat. Simul. 2010, 2, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cernicova-Buca, M. Communicating an unpopular European topic: The refugee crisis reflected by Romanian media. In Proceedings of the 5th International Multidisciplinary Scientific Conference on Social Sciences and Arts SGEM 2018, Albena, Bulgaria, 26 August–1 September 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blakeslee, S. The CRAAP Test. LOEX Q. 2004, 31, 4. Available online: https://commons.emich.edu/loexquarterly/vol31/iss3/4 (accessed on 15 November 2021).

- Magazzini, T. In the Eye of the Beholder? Minority Representation and the Politics of Culture. In Visual Methodology in Migration Studies; Nikielska-Sekula, K., Desille, A., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 275–292. [Google Scholar]

- Guan, T.; Liu, T.; Yuan, R. Facing disinformation: Five methods to counter conspiracy theories amid the Covid-19 pandemic. Comunicar 2021, 29, 71–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weijers, R.J.; de Koning, B.B.; Paas, F. Nudging in education: From theory towards guidelines for successful implementation. Eur. J. Psychol. Educ. 2020, 36, 883–902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Teamwork | “Working with people is not easy, especially when the team is made up of different people and who inevitably have different views on certain aspects. But these differences of opinion can be constructive, so it is important to listen and communicate, so the relations between us are important too”. “I have noticed that I like to coordinate a team. Also, work is much easier and more enjoyable when several people collaborate”. “Overall, it was nice to be part of the team, although at the beginning we had to overcome small organizational obstacles; ultimately we were able to meet and bring the task to the end”. “I learned that a team works well if there is collaboration, empathy, and good communication”. “The game helped me realize that teamwork is easier than individual work, due to the fact that the tasks are divided, and you have someone to counsel with, so that the outcome is better (than in individual work)”. |

| Experimenting with strategies aiming to manipulate audiences | “It was interesting, because I was not acquainted with these strategies until the time of the game, and the dynamic experience made me understand the issue much easier than during academic lectures”. “Manipulation strategies have always been used, either to shed a positive light on a villain or to bury the career of others. Regardless of the subject, each communicator has his/her own principles, needs, and so on. It is not new for certain communicators to manipulate audiences against or towards something in a particular topic”. “Given that you can control your audience through that article, it requires a series of strategies that can either capture attention in a positive sense (arouse curiosity) or misinform your audience about important news.” “I learned many new things about the roles that a news story plays and (I understood how) to observe the manipulation”. |

| The importance of the style/framing for content production and editing | “I have noticed that the style of writing is sometimes more important than the elements communicated in a material”. “I noticed how much the style chosen for writing alters the result; I think we need to be much more careful, because by writing in the wrong register, our intentions may not be correctly understood”. “The editorial style is a very important one, because it determines whether the audience perceives the information reported, in the way in which it should be understood”. “The game made me aware that news can be written in many ways, and those who write it may have other intentions/agendas than those to present the truth as it is”. |

| Issues to look for in understanding and deconstructing a media message | “The game helped me better understand what the competence of critical thinking means”. “We learned how manipulation/disinformation can be dismantled”. “It is very important to get to know ourselves first what criteria to check information to apply, before believing absolutely everything we see, hear or read”. “In order to understand a news story well, you need to know how to pass it through certain filters, these being the critical grids”. |

| Role | Gamification 1 (% of Correct Responses) | Gamification 2 (% of Correct Responses) |

|---|---|---|

| sensationalist | 31% | 38.2% |

| reductionist | 88.1% | 67.6% |

| conspirationalist | 76.2% | 47.1% |

| alarmist | 38.1% | 47.1% |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Cernicova-Buca, M.; Ciurel, D. Developing Resilience to Disinformation: A Game-Based Method for Future Communicators. Sustainability 2022, 14, 5438. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14095438

Cernicova-Buca M, Ciurel D. Developing Resilience to Disinformation: A Game-Based Method for Future Communicators. Sustainability. 2022; 14(9):5438. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14095438

Chicago/Turabian StyleCernicova-Buca, Mariana, and Daniel Ciurel. 2022. "Developing Resilience to Disinformation: A Game-Based Method for Future Communicators" Sustainability 14, no. 9: 5438. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14095438

APA StyleCernicova-Buca, M., & Ciurel, D. (2022). Developing Resilience to Disinformation: A Game-Based Method for Future Communicators. Sustainability, 14(9), 5438. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14095438