Abstract

The coffee industry has grown into a highly competitive management environment, which has led to the contemplation of differentiated marketing strategies as tools for business success. Practitioners operate their own SNS brand pages to encourage customers to participate and engage in two-way interpersonal marketing practices that can generate value co-creation. This paper aims to explore the relationships among the types of value offered by SNSs, brand attitude, and customer value-co-creation behaviors in the hospitality context, by employing the Value–Attitude–Behavior model. Data were collected via an online survey research company and analyzed by PLS-SEM using SmartPLS 3.0 and Jamovi 1.0 software packages. A quantitative research method was carried out with a total of 406 adults in South Korea who had had both on-site and SNS coffee brand experiences within three months of the survey. The results of this study can be summarized as follows. First, information-seeking, entertainment, and expressive value all had a significant positive effect on brand attitude. Second, brand attitude had a significant positive effect on both customer participation behaviors and customer citizenship behaviors. The results of the current study suggest useful implications in that the usage of SNSs as marketing communication tools can influence not only online but also offline brand attitudes and customer value-co-creation behaviors.

1. Introduction

The coffee industry’s growing market provides exciting opportunities, but also challenges, due to its highly competitive management environment. Additionally, the COVID-19 pandemic has resulted in enormous changes in service settings [1]. The current situation has been catastrophic for the hospitality industry forcing businesses to reduce service encounters that are essential to the service process [2]. Given the managerial difficulties that practitioners are facing, differentiated marketing strategies to communicate with customers are required in the coffee industry [3].

Creating value through business is the ultimate goal for corporations. Due to the inseparable and heterogeneous nature of service in the hospitality context, customers are considered as active partners of firms because they play significant roles in the process of producing service and creating value [4,5]. Interactions between a brand and its customers are a significant factor that can evoke various beneficial behavioral outcomes, such as co-creation of brand value [6]. Therefore, how to encourage customers to engage in successful service processes that create value has been a crucial research subject in academia for many years.

Customers’ value-co-creation behaviors frequently occur in online service settings. In fact, virtual environments, such as social network services (SNSs), are considered easier and more efficient platforms for triggering co-creation behaviors than offline spaces, because SNSs prominently feature prompt responses with fewer time and space limitations [7,8]. Via SNS, customers can input resources, such as time, effort, knowledge, opinions, attitudes, information, and accounts of experiences regarding a brand, while interacting with the brand or other customers and creating value for the firm and themselves [9]. Expanded service settings are also cost-effective for enticing customers to engage in co-creation [4,10]. For example, Starbucks, which leads the coffee industry in Korea, has garnered more than 0.82 million followers and 1.5 thousand posts on Instagram. Along with the followers of the Starbucks page, other SNS users are frequently exposed to the Starbucks page or posts, gaining the opportunity to participate in brand-marketing communication activities.

Hence, most coffee brands, large or small, have created and optimized official brand pages through various SNS channels, such as Instagram, Facebook, Youtube, and Twitter, to allow customers to simultaneously participate in marketing interactions in real time. Because SNSs are already part of the ordinary lives of ‘fan’ or ‘guest’ customers of a brand, they are pervasively used by marketers, not only to market a brand’s products and services, but also to directly communicate and build lasting relationships with customers in order to co-create value [8,11,12,13]. Online activities, such as following, liking, commenting, making recommendations, exchanging information, and other similar activities, are all considered convenient and active marketing interactions between brands and customers [6,12,14].

SNSs allow for two-way communication [4,8,15]. Thus, the features of SNSs as marketing communication tools are essential for the success of SNS marketing and, at the same time, critical for customer value-co-creation behaviors [8,16]. Despite the importance of SNSs as prominent channels for customer value-co-creation behaviors, relatively little attention has been paid to the relationship between them [16]. Because these networks have huge numbers of users, they offer a key platform in the context of many-to-many interaction, which in turn yields valuable marketing intelligence a brand can use to co-create value beyond purchasing [14,17,18].

Given the attention directed toward the increased usage of SNSs as marketing interaction tools and customer value-co-creation behaviors, a research question emerges: Does the perceived value of using SNSs as marketing tools, as promoted by the SNSs themselves, translate to customers engaging in actual value-co-creation behaviors? Customers’ interactive experiences can lead to value creation by forming relationships between stakeholders [13,19,20]. However, few studies have investigated the impact of brand SNS experiences on brand attitude and value-co-creation behaviors. Using Homer and Kahle’s (1988) Value–Attitude–Behavior model, the current study looks in detail at the dimensions of the perceived value of using SNSs, and their effects on brand attitude and customer value-co-creation behavior [21].

In summary, the purpose of this study was to fill this research gap. First, this study aimed to present academic and practical evidence indicating which dimensions of the perceived value of using brand SNS pages significantly affect brand attitude. Second, this study also attempted to assess whether brand attitude significantly affects customer value-co-creation behaviors. The results of the current study are expected to provide a theoretical and practical foundation for current practitioners and future studies in that it deals with both online and on-site value-co-creation experiences in the coffee industry.

2. Literature review

2.1. Value–Attitude–Behavior Model (VAB Model)

The Value–Attitude–Behavior model has been consistently adopted by researchers to explain consumer behavior in various fields [22]. The model consists of three components arranged in hierarchical order: value, attitude, and behavior [21]. According to Homer and Kahle (1988) [21], abstract values in the cognitive domain indirectly influence specific behaviors through the midrange attitude. The concept of attitude in this context is defined as a tendency to evaluate a brand favorably or unfavorably, which can determine behavioral variables [22,23]. Values are more fundamental than attitudes in the hierarchical structure, whereas intentions to behave or actual behaviors follow attitudes [21,24]. Therefore, according to the model, the perception of value and a positive attitude toward a brand can actually initiate beneficial customer behaviors. A broad range of consumer behaviors in the context of the hospitality industry has been explained with the VAB model [22,23,24,25,26]. For example, Teng et al. (2014) [22] claimed that personal values significantly and positively affect attitudes toward health and the environment, and attitudes also have a significantly positive effect on revisit and recommendation intentions. Shin et al. (2017) [24] pointed out that willingness to pay more can result from pro-environmental attitudes and the consumption values of customers. Compared to prior research dealing with values regarding actual consumption, studies on the perceived value of using SNSs have not been sufficiently discussed, in spite of the gravity of this issue. The current study applied the VAB model to explicate the impacts of the perceived value of using a SNS, which is an online service environment, on attitudes and customer value-co-creation behaviors.

2.2. Perceived Value of Using SNSs and Brand Attitude

Despite the widespread adoption of SNSs, researchers have paid little attention to the perceived value of using them as a marketing platform. This study aimed to elucidate the multiple dimensions of the value of using SNSs for this purpose, and considered both the cognitive and emotional aspects of this value. The conventional approach to comprehending value relates to consumption behaviors. Sheth et al. (1991) [27] defined value as the standard resulting from a comparison of expenses to benefits. However, there have been various attempts by many researchers to define the multiple dimensions of value. For example, Sweeny and Soutar (2001) [28] refined the definition of consumption value for customers to include emotional, social, price, and performance components, and developed a measuring scale, PERVAL, based on the suggestion of Sheth et al. (1991) [27]. Smith and Colgate (2007) [29] argued that a multidimensional approach that considers the context of the situation is necessary to clarify a variety of types of value. They suggested four types of value: functional, hedonic, symbolic, and cost. In line with the previous research, this study attempted to identify the specific dimensions of the perceived value of interaction experiences via SNS brand pages in the coffee industry.

Based on a review of the literature, this paper proposes four types of value that can be gained by using SNSs: information-seeking, entertainment, expressive, and economic [19,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35]. First, information-seeking value is conceptualized as the ways in which customers fulfill their cognitive needs by searching for epistemic or novel value on SNSs [19,27]. Customers perceive value when information about the brand is exact, useful, and up-to-date. Second, entertainment value is perceived in terms of emotional value, such as happiness, excitement, joy, or pleasure, gained by using SNSs [19,28,31]. Third, expressive value is perceived when customers can show, express, and share their self-identity, opinions, or faith via SNSs [19,29,32]. Lastly, economic value refers to benefits in terms of price or service quality that customers can obtain by using SNSs [19,27,28,33]. When customers recognize that using a brand’s SNS gives them access to better prices or service offers, then economic value is perceived.

Attitudes are associated with specific objects, such as a brand in the current study. Brand attitude refers to customers’ overall evaluations of a brand derived by synthesizing brand-relevant experiences at various levels, such as communication, purchasing, or usage [36,37]. When customers have an affirmative brand attitude, they tend to positively and favorably evaluate the brand. Brand attitude can also be related to non-product and symbolic attributes, and thus should be considered as a significant factor influencing diverse consumer behaviors [36,37].

Some scholars have confirmed the significant role of SNSs, not only in terms of providing information but also promoting exchanges of experiences and values, and in turn, influencing brand attitude in the hospitality context [38,39,40]. Song and Yoo (2016) [38] argued that customers of hotels and restaurants perceive using SNSs in the early stages of the purchase-decision-making process as providing informational, economic, and entertainment value. They found that these dimensions of value derived from SNSs influence the final choice. However, this study ignored the aspect of attitude. Other research demonstrated that the informational, expressive, and emotional benefits of participation behaviors on SNSs significantly and positively affect attitude [39]. Carlson et al. (2019) [40] showed that active interaction among customers on SNS pages generated informational, emotional, and relational value, thereby affecting satisfaction and relationship quality. The results of the prior studies suggest the possibility of a positive relationship between the perceived value of using SNSs and brand attitude in the context of the coffee industry. Based on the preceding discussions, the following hypotheses were proposed:

Hypothesis 1.

The perceived value of using SNSs has a significantly positive effect on brand attitude.

H1-1.

The perceived information-seeking value of using SNSs has a significantly positive effect on brandattitude.

H1-2.

The perceived entertainment value of using SNSs has a significantly positive effect on brand attitude.

H1-3.

The perceived expressive value of using SNSs has a significantly positive effect on brand attitude.

H1-4.

The perceived economic value of using SNSs has a significantly positive effect on brand attitude.

2.3. Customer Value-Co-Creation Behavior: Participation and Citizenship

Unlike the traditional view of customers as receivers or passive buyers of the value that firms provide, modern customers can take part in creating value with firms, according to service-dominant logic (S-D logic) [41]. Customers become human resources through involvement in the value creation process, and can help to improve the performance of companies [41,42,43]. This significance of the active roles of customers may be of even greater importance in the hospitality sphere, because mutual interactive cooperation that co-creates value is frequently performed [43].

Customer value-co-creation behavior pertains to the collaborative activities businesses and customers engage in, such as interacting and sharing their ideas and experiences, that contribute to creating value for both customers and businesses alike [42,44,45]. Customer value-co-creation behavior includes two components: customer participation behaviors and customer citizenship behaviors [42,45]. Participation behaviors refer to the in-role activities of customers that are essential to the service process, whereas citizenship behaviors refer to extra-role activities customers engage in that provide richer value beyond what is expected for the firm [42,44,45].

Yi and Gong (2013) [42] conceptually separated value-co-creation behaviors into participation behaviors and citizenship behaviors, and suggested measurement scales to be used specifically for service industries. According to their research, customer participation behaviors include four first-order elements: information seeking, information sharing, personal interaction, and responsible behavior [42,46]. These are required and essential behaviors customers must engage in to successfully complete the service process [42,47]. For example, when customers plan to use a certain brand, they might search for information about the brand to ensure a satisfying user experience. Furthermore, when customers are physically in the shop, the delivery of the service can only be completed through cooperative interactions between the staff of the brand and the customer. Customer citizenship behaviors also include four first-order factors: advocacy, helping, tolerance, and feedback [42,46]. However, citizenship behaviors are voluntarily performed for the brand by customers who invest tangible and intangible resources into the relationship and, thereby, provide extraordinary value for a firm [42,47]. Positive comments about the brand, recommendations, or being more patient regardless of a service failure are all examples of citizenship behaviors. In line with Yi and Gong (2013) [42], this research also defines customer value-co-creation behavior in terms of two categories [46,47].

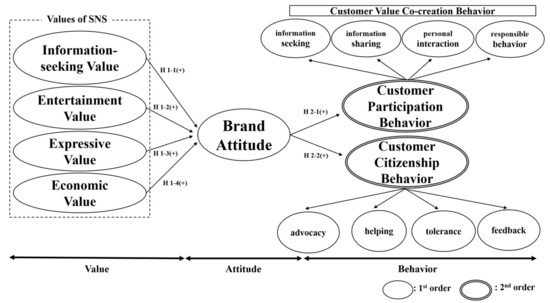

Brand attitude is related to customer behaviors, as mentioned above, and customer value-co-creation behaviors are not an exception. Zadeh et al. (2019) [9] provided empirical evidence indicating that attitudes formed by informational interactions on SNSs significantly affect intentions to perform participation and citizenship behaviors. Prior research focused on the co-creation experience in the tourism industry and suggested that tourists’ attitudes have a positive effect on brand co-creation [48]. Moreover, Frasquet-Deltoro et al. (2019) [16] pointed out the necessity of research on how to derive value from co-creation behaviors in both offline and online contexts. In this respect, the current study adopted the VAB model to explain brand attitude as an antecedent of comprehensive customer value-co-creation behaviors [21]. The research model with hypothesis is proposed in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Research model.

Hypothesis 2.

Brand attitude has a significantly positive effect on customer value-co-creation behaviors.

H2-1.

Brand attitude has a significantly positive effect on customer participation behaviors.

H2-2.

Brand attitude has a significantly positive effect on customer citizenship behavior.

3. Methodology

3.1. Data Collection

The current study employed a self-administered quantitative research method to indicate relationships among the perceived value of using SNSs, brand attitude, and customer value-co-creation behaviors. Respondents were required to choose one coffee brand which they have experienced both in the SNS page and in the coffee shops. The survey targeted coffee brands actively operating official brand pages on SNSs (Instagram, Facebook, Youtube, and Twitter). Additionally, the price of one cup of coffee (above 4100 won), the brand value of the coffee brand, and the number of shops (at least over 150) were all considered when selecting coffee brands in the survey.

A pretest was conducted with 30 people to check the clarity of measurement scales and ensure the validity and reliability of the survey. The questionnaires were revised based on comments after the pretest. Data were collected via an online survey research company from 23 September to 7 October 2021. A total of 406 adults in South Korea who had both on-site and SNS coffee brand experiences within three months participated in the main study.

3.2. Measurements

To compile demographic information, respondents were asked about their gender, age, income per month, education level, and occupation. Items developed by Flores and Vasquez-Parraga (2015) [33], Han and Kim (2020) [34], Pandey and Kumar (2020) [19], Ryu et al. (2010) [35], and Sheth et al. (1991) [27] were modified and adapted to measure the perceived value of using SNSs: information-seeking value (4 items), entertainment value (4 items), expressive value (4 items), and economic value (4 items), respectively. Four measurement items regarding brand attitude were adopted from Langaro et al. (2018) [36]. Customer co-creation behaviors consisted of eight first-order constructs with 27 measurement items: customer participation behaviors (14 items) and customer citizenship behaviors (13 items) [16,42,47]. Both were analyzed as second-order factors with four first-order factors each. Participation behaviors included information seeking (3 items), information sharing (3 items), responsible behavior (4 items), and personal interaction (4 items), while citizenship behavior included feedback (3 items), advocacy (3 items), helping (4 items), and tolerance (3 items). Given that customer co-creation behaviors are more easily performed in online environments, the measurement scales consider both online and onsite service settings [16]. A seven-point Likert scale from 1 “strongly disagree” to 7 “strongly agree” was used to measure all the variables.

3.3. Data Analysis

Partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) was employed to analyze the collected data, using SmartPLS 3.2.9 and JAMOVI 1.0 software packages. The first part of this study included descriptive statistical analysis and correlation analysis, followed by measurement model analysis employing bootstrapping methodology (5000 resamples) [49,50]. The reliability and validity of the measurement model were assessed according to the two-step approach recommended by Hair et al. (2017) [49]. The second part of the current study assessed the structural model with a hierarchical component approach. The first-order constructs were repeatedly used for two second-order constructs to confirm the formation of the measurement model.

4. Results

4.1. Demographic Analysis

Among the 406 participants, 199 were male (49.01%), while 207 were female (50.99%). The majority of respondents were in their 20s (37.19%) and 30s (34.24%), which aligns with the majority of SNS users. Approximately 68% of the sample had bachelor’s level qualifications, with office workers (45.57%) being most heavily represented. The characteristics of the respondents are reported in Table 1.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics (N = 406).

4.2. Measurement Model

First, Cronbach’s α, Rho_A, composite reliability (CR), outer factor loadings, and average variance extracted (AVE) were assessed to support the reliability and validity of the constructs. An acceptable level for Cronbach’s α coefficients, Rho_A, and CR to achieve internal consistency is 0.70 [50]. AVE should exceed 0.5, and the factor loadings should surpass 0.7 to achieve convergent validity [50]. All the indexes were above these standards, thereby confirming internal consistency, reliability, and convergent validity. Table 2 represents the results of the measurement model properties. Second, discriminant validity was tested with the Fornell–Larcker criterion [51], comparing the square roots of AVE and correlations among the constructs. All the reported square roots of AVEs were adequately greater than the correlations, which established discriminant validity (see Table 3).

Table 2.

Measurement properties.

Table 3.

Discriminant validity: Fornell–Larcker criterion.

4.3. Structural Model

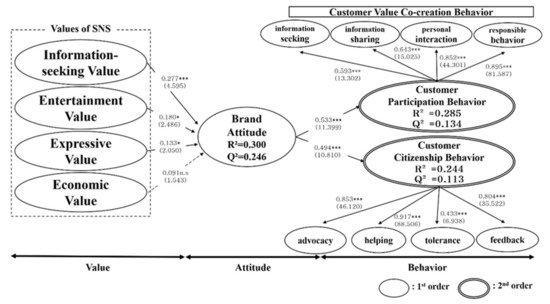

In the second part of the current study, collinearity was examined with VIF values before the hypotheses were estimated. VIF values under 3 were acceptable. The results of all constructs ranged from 1.000 to 2.554, indicating there was no concern of collinearity with the model [50]. Each correlation coefficient between the eight first-order structures and two second-order structures, participation behavior and citizenship behavior, was statistically significant (p < 0.000): information seeking (β = 0.593), information sharing (β = 0.643), personal interaction (β = 0.852), responsible behavior (β = 0.895), feedback (β = 0.804), advocacy (β = 0.853), helping (β = 0.917), and tolerance (β = 0.433). This suggests that higher-order structures formed well and explained the correlation with lower-order factors.

The R2 values refer to the power of how well the latent variables predicted the constructs: brand attitude ( = 0.300), customer participation behavior ( = 0.285), and customer citizenship behavior ( = 0.244). Moreover, Stone-Geisser’s values were calculated using a blindfolding procedure to indicate the predictive power of the model [51,52]. All of the values were above zero, thereby demonstrating a high ability to predict [53]. Lastly, the suggested hypotheses were further assessed by examining the t-value and path coefficient with PLS-SEM algorithm analysis (see Table 4). First, the paths H1-1, H1-2 and H1-3 were supported. Perceived information-seeking value (β = 0.277, p < 0.000), entertainment value (β = 0.180, p < 0.05), and expressive value (β = 0.133, p < 0.05) via SNS usage had significantly positive effects on brand attitude. The economic value of using SNSs, however, did not significantly affect brand attitude (H1-4, β = 0.091). Second, brand attitude had positive and significant impacts on customer value-co-creation behaviors, including both customer participation behaviors (β = 0.533, p < 0.000) and customer citizenship behaviors (β = 0.494, p < 0.000), thereby supporting both H2-1 and H2-2. The result of the hypothesis testing is shown in Figure 2.

Table 4.

Hypothesis testing.

Figure 2.

Result of Hypothesis Testing. *** p < 0.001, * p < 0.05, n.s. not significant.

5. Conclusions

5.1. Discussion

Prior studies have demonstrated the importance of using SNSs as marketing interaction channels in the hospitality context. However, knowledge regarding relationships between SNSs values and value-co-creation behaviors is still scarce. The current study aimed to confirm the impacts of using coffee brand SNSs on brand attitude and customer value-co-creation behaviors drawing on the VAB model. The results of the study can be summarized as follows. First, perceived information-seeking, entertainment, and expressive value significantly and positively affected customers’ brand attitudes. Information-seeking value showed the greatest significance (mean = 5.32, β = 0.277), then entertainment value (mean = 4.55, β = 0.180), and finally expressive value (mean = 3.98, β = 0.133). This finding aligns with the assertion of previous research that the informational function of SNSs is substantial. At the same time, the result suggests that the aspects of entertainment and expressive values should be also considered. The function of providing information has typically been the focus of practitioners. However, given these results, utilizing coffee brand SNSs as interactive tools for creating multiple forms of value seems critical.

In contrast, the research hypothesis regarding the economic value (H1-4) of using SNSs was not supported, which does not align with the antecedent research [36,54]. This contradiction may be explained by the samples used by past studies dealing with the economic value of SNSs. Those studies targeted customers who had hotel or restaurant experiences. In contrast, the expenses of coffee brand customers are relatively trivial, and therefore may not seem like a large enough purchase to constitute perceived economic benefit through SNSs. Though the effect of the economic value of using SNSs was not statistically significant, the result showed 0.123 significance level with β = 0.091. Thus, the result may still imply a positive relationship between economic value and brand attitude.

Second, the results showed that brand attitude had a significant effect on both customer participation behaviors and customer citizenship behaviors. These results indicate that customers’ overall evaluations of a brand are a very important factor in terms of the midrange role between the value gained from SNSs and actual customer value-co-creation behaviors. The VAB model appositely explained the relationship among the three main variables.

Furthermore, the behavioral variables of the current study comprehensively reflected both online and onsite service settings. In summary, the results of the study implied that the perceived value of using SNSs can entice customers to perform value-co-creation behaviors in both online and offline environments through the fostering of brand attitudes. Moreover, customer behaviors that co-create value can consequently generate various types of usage value in the virtual environment, forming a virtuous circle.

5.2. Theoretical Implications

This study contributes to the coffee industry management literature by confirming the effectiveness of a multi-dimensional approach to the perceived value of using SNSs and brand attitude as antecedents of customer value-co-creation behaviors. The current study explored and identified four types of value: information-seeking, entertainment, expressive, and economic, based on literature and empirical evidence. Few previous researchers have paid attention to the different types of perceived value associated with using SNSs as a consequence of marketing communications, or have respectively examined these values in the context of the coffee industry. Thus, this result is expected to expand theoretical approaches to SNSs in the foodservice industry.

Moreover, based upon the VAB model, this study proposed brand attitude as an antecedent of customer value-co-creation behaviors. Prior research demonstrated that interacting on SNSs can build and enhance the relationship quality between a brand and its customers. Similarly, the result of this study showed that active participation in SNSs also resulted in brand attitude, which consequently related to customer participation behaviors and customer citizenship behaviors.

Additionally, the current study attempted to examine customer participation behaviors and customer citizenship behaviors using multi-layer factors corresponding to four sub-constructs each. The significant relationships among the constructs suggested theoretical implications for future customer value-co-creation behavior research in the context of the coffee industry.

Lastly, the findings contribute to better comprehension of the considerable impacts of SNS usage on both online and offline value-co-creation behaviors in the coffee industry. Most past research has solely focused on either SNS or on-site interactive brand experiences, even though in these times, these experiences may be happening simultaneously. Thus, this study can provide distinctive research insights in terms of derived comprehensive value-co-creation behaviors based on the different dimensions of value associated with SNSs and brand attitude.

5.3. Managerial Implications

The results of this study also suggest practical recommendations for marketing practitioners in the coffee industry. First, coffee brands should offer diverse marketing interaction experiences, so that customers perceive that they receive various types of value by using SNSs. Particularly, marketing managers should recognize the information-seeking value type as a key benefit of SNS brand pages. To enhance this value, providing exact and useful information is needed. Further, SNS pages must provide up-to-date and various brand information to customers. Moreover, emotional/personal aspects should also be emphasized according to the empirical evidence of the current study, which highlights the importance of entertainment value and expressive value on SNSs as well. Customers can feel pleasant, entertained, and interested through participation behaviors on brand SNS pages. Furthermore, interaction activities with a brand and other customers on a SNS page can allow customers to express their inner selves. Therefore, it is recommended that coffee brand marketers consider the multiple benefits of using SNSs and endeavor to provide as many types of value as possible.

Second, establishing brand attitude through SNS interactions can be a double-edged sword. While online experiences can substantially impact customers, at the same time, these interactions tend to be more difficult for practitioners to control in terms of the breadth and depth of the effect. Therefore, the industry should understand the ‘ripple effect’ of using SNSs as a marketing method, and pay attention to interactions with customers to prevent generating negative impressions toward the brand via its SNS.

Third, marketing professionals should pay attention to customer citizenship behaviors in online service settings. SNSs can weaken communication barriers between a brand and its customers, thereby greatly facilitating citizenship behaviors. Customer citizenship behaviors, in contrast to required participation behaviors, are discretionary activities that customers perform, and are helpful to both the service company and the customer. For example, customers can say positive things or recommend the brand to other customers. Additionally, they can act as ‘brand ambassadors’ by assisting and advising other customers regarding the brand. The brand can sometimes receive direct feedback regarding products and services via customer citizenship behaviors. The performance of the brand can be enhanced through such volunteer value-co-creation behaviors. According to prior research, it can lead to beneficial consequences, such as service quality, satisfaction, and brand loyalty [16,55,56,57]. Therefore, it is necessary for practitioners to actively use SNSs as strategic tools to involve customers in citizenship behaviors.

5.4. Limitations and Future Study

Despite the contributions of this study, it does have several limitations that suggest insights for future research. First, the current research was limited to the context of the coffee industry in Korea only. Thus, future studies can apply these constructs to other foodservice segments; or can be generalized across different industries. Second, the sample consisted of customers who had both SNS and on-site experiences with a coffee brand. Examining the impacts of SNSs on customers who have less experience with a brand could be another research opportunity. Third, the results of the study did not support the hypothesis that the economic value of using SNSs impacted brand attitude. Therefore, future studies can modify the measurement scale for economic value in the conceptual model. Fourth, the current study alternatively assessed customer value-co-creation behaviors as higher-order factors. Respective analysis can be conducted in future studies examining first-order factors of participation and citizenship behaviors as research constructs. Finally, the research model of this study did not consider any moderators. Future studies may elect to investigate moderating effects derived from various theories that can potentially suggest impactful insights.

Author Contributions

This article is based on the Master thesis of A.-M.K., which was completed at Kyung Hee University. A.-M.K. worked on the conceptual development of the manuscript and data collection and analysis and also wrote the manuscript. Y.N. reviewed, edited, and offered overall guidance for publishing the manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Duarte Alonso, A.; Kok, S.K.; Bressan, A.; O’Shea, M.; Sakellarious, N.; Koresis, A.; Buitrago Solis, M.A.; Santoni, L.J. COVID-19, aftermath, impacts, and hospitality firms: An international perspective. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2020, 91, 102654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, L.; Fan, A.; Yang, Y.; He, Z. Tech-touch balance in the service encounter: The impact of supplementary human service on consumer responses. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2022, 101, 103122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.A.; Jung, H.Y. Effects of SNS’s characteristics of coffee shops on customer satisfaction and purchasing intention. Culin. Sci. Hosp. Res. 2021, 27, 84–93. [Google Scholar]

- Kang, J.W.; Lee, H.; Namkung, Y. The impact of restaurant patrons’ flow experience on SNS satisfaction and offline purchase intentions. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2018, 30, 797–816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, E.; Tang, L.; Bosselman, R. Customer perceptions of innovativeness: An accelerator for value co-creation. J. Hosp. Tour. Res. 2019, 43, 807–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheung, M.L.; Pires, G.; Rosenberger, P.J.; De Oliveira, M.J. Driving consumer–brand engagement and co-creation by brand interactivity. Mark. Intell. Plan. 2020, 38, 523–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlson, J.; Rahman, M.; Voola, R.; De Vries, N. Customer engagement behaviours in social media: Capturing innovation opportunities. J. Serv. Mark. 2018, 32, 83–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kotler, P.; Bowen, J.T.; Makens, J.C.; Baloglu, S. Marketing for Hospitality and Tourism; Pearson: Essex, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Zadeh, A.H.; Zolfagharian, M.; Hofacker, C.F. Customer-customer value co-creation in social media: Conceptualization and antecedents. J. Strateg. Mark. 2019, 27, 283–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.J.; Jang, A. A longitudinal study of sales promotion on social networking sites (SNS) in the lodging industry. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2021, 48, 256–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.H.; Huang, S.C.T.; Tsai, C.Y.D.; Lin, P.Y. Customer citizenship behavior on social networking sites: The role of relationship quality, identification, and service attributes. Internet Res. 2017, 27, 428–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sashi, C.M.; Brynildsen, G.; Bilgihan, A. Social media, customer engagement and advocacy: An empirical investigation using Twitter data for quick service restaurants. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2019, 31, 1247–1272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.W.; Teng, H.Y.; Chen, C.Y. Unlocking the customer engagement-brand loyalty relationship in tourism social media: The roles of brand attachment and customer trust. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2020, 44, 184–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.M.; Kang, J.W.; Namkung, Y. Instagram users’ information acceptance process for food-content. Sustainability 2021, 13, 2638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dessart, L. Social media engagement: A model of antecedents and relational outcomes. J. Mark. Manag. 2017, 33, 375–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frasquet-Deltoro, M.; Alarcón-Del-Amo, M.D.C.; Lorenzo-Romero, C. Antecedents and consequences of virtual customer co-creation behaviours. Internet Res. 2019, 29, 218–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tussyadiah, S.P.; Kausar, D.R.; Soesilo, P.K.M. The effect of engagement in online social network on susceptibility to influence. J. Hosp. Tour. Res. 2018, 42, 201–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shawky, S.; Kubacki, K.; Dietrich, T.; Weaven, S. A dynamic framework for managing customer engagement on social media. J. Bus. Res. 2020, 121, 567–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandey, S.; Kumar, D. Customer-to-customer value co-creation in different service settings. Qual. Mark. Res. 2020, 23, 123–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neghina, C.; Caniëls, M.C.J.; Bloemer, J.M.M.; Van Birgelen, M.J.H. Value cocreation in service interactions: Dimensions and antecedents. Mark. Theory 2015, 15, 221–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Homer, P.M.; Kahle, L.R. A structural equation test of the value-attitude-behavior hierarchy. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1988, 54, 638–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teng, Y.M.; Wu, K.S.; Huang, D.M. The influence of green restaurant decision formation using the VAB model: The effect of environmental concerns upon intent to visit. Sustainability 2014, 6, 8736–8755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kim, M.J.; Hall, C.M.; Kim, D.K. Predicting environmentally friendly eating out behavior by value-attitude-behavior theory: Does being vegetarian reduce food waste? J. Sustain. Tour. 2020, 28, 797–815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, Y.H.; Moon, H.; Jung, S.E.; Severt, K. The effect of environmental values and attitudes on consumer willingness to pay more for organic menus: A value-attitude-behavior approach. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2017, 33, 113–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jun, J.; Kang, J.; Arendt, S.W. The effects of health value on healthful food selection intention at restaurants: Considering the role of attitudes toward taste and healthfulness of healthful foods. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2014, 42, 85–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chen, A.; Peng, N. Examining consumers’ intentions to dine at luxury restaurants while traveling. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2018, 71, 59–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheth, J.N.; Newman, B.I.; Gross, B.L. Why we buy what we buy: A theory of consumption values: Discovery service for air force institute of technology. J. Bus. Res. 1991, 22, 159–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sweeney, J.C.; Soutar, G.N. Consumer perceived value: The development of a multiple item scale. J. Retail. 2001, 77, 203–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, J.B.; Colgate, M. Customer value creation: A practical framework. J. Mark. Theory Pract. 2007, 15, 7–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holbrook, M.B. Customer value and autoethnography: Subjective personal introspection and the meanings of a photograph collection. J. Bus. Res. 2005, 58, 45–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minkiewicz, J.; Evans, J.; Bridson, K. How do consumers co-create their experiences? An exploration in the heritage sector. J. Mark. Manag. 2014, 30, 30–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tynan, C.; McKechnie, S.; Hartley, S. Interpreting value in the customer service experience using customer-dominant logic. J. Mark. Manag. 2014, 30, 1058–1081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flores, J.; Vasquez-Parraga, A.Z. The impact of choice on co-produced customer value creation and satisfaction. J. Consum. Mark. 2015, 32, 15–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, S.L.; Kim, K. Role of consumption values in the luxury brand experience: Moderating effects of category and the generation gap. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2020, 57, 102249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryu, K.; Han, H.; Jang, S.S. Relationships among hedonic and utilitarian values, satisfaction and behavioral intentions in the fast-casual restaurant industry. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2010, 22, 416–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langaro, D. Rita, P.; De Fátima Salgueiro, M. Do social networking sites contribute for building brands? Evaluating the impact of users’ participation on brand awareness and brand attitude. J. Mark. Commun. 2018, 24, 146–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keller, K.L. Conceptualizing, measuring, and managing customer-based brand equity. J. Mark. 1993, 57, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, S.; Yoo, M. The role of social media during the pre-purchasing stage. J. Hosp. Tour. Technol. 2016, 7, 84–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Constantinides, E.; Brünink, L.A.; Lorenzo-Romero, C. Customer motives and benefits for participating in online co-creation activities. Mark. Advert. 2015, 9, 21–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlson, J.; Wyllie, J.; Rahman, M.M.; Voola, R. Enhancing brand relationship performance through customer participation and value creation in social media brand communities. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2019, 50, 333–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grönroos, C. Service logic revisited: Who creates value? And who co-creates? Eur. Bus. Rev. 2008, 20, 298–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, Y.; Gong, T. Customer value co-creation behavior: Scale development and validation. J. Bus. Res. 2013, 66, 1279–1284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quach, S.; Shao, W.; Ross, M.; Thaichon, P. Customer engagement and co-created value in social media. Mark. Intell. Plan. 2020, 38, 730–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, S.; Yang, S.; Ma, M.; Huang, J. Value co-creation on social media: Examining the relationship between brand engagement and display. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2018, 30, 2153–2174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assiouras, I.; Skourtis, G.; Giannopoulos, A.; Buhalis, D.; Koniordos, M. Value co-creation and customer citizenship behavior. Ann. Tour. Res. 2019, 78, 102742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, Y.; Nataraajan, R.; Gong, T. Customer participation and citizenship behavioral influences on employee performance, satisfaction, commitment, and turnover intention. J. Bus. Res. 2011, 64, 87–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, E.; Tang, L. The role of customer behavior in forming perceived value at restaurants: A multidimensional approach. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2020, 87, 102511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rather, R.A. Monitoring the impacts of tourism-based social media, risk perception and fear on tourist’s attitude and revisiting behaviour in the wake of COVID-19 pandemic. Curr. Issues Tour. 2021, 24, 3275–3283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Hult, G.T.M.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. A Primer on Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM); Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.F.; Risher, J.J.; Sarstedt, M.; Ringle, C.M. When to use and how to report the results of PLS-SEM. Eur. Bus. Rev. 2019, 31, 2–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stone, M. Cross-validatory choice and assessment of statistical predictions. J. R. Stat. Soc. Ser. B. 1974, 36, 111–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geisser, S. Effect to the random model A predictive approach. Biometrika 1974, 61, 101–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahn, J.; Lee, C.K.; Back, K.J.; Schmitt, A. Brand experiential value for creating integrated resort customers’ co-creation behavior. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2019, 81, 104–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, J.; Wong, I.K.A.; King, B.; Liu, M.T.; Huang, G.Q. Co-creation and co-destruction of service quality through customer-to-customer interactions: Why prior experience matters. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2019, 31, 1309–1329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shulga, L.; Busser, J.A.; Bai, B.; Kim, H. The reciprocal role of trust in customer value co-creation. J. Hosp. Tour. Res. 2021, 45, 672–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, S.K.; Balaji, M.S.; Soutar, G.; Jiang, Y. The antecedents and consequences of value co-creation behaviors in a hotel setting: A two-country study. Cornell Hosp. Q. 2020, 61, 353–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).