Abstract

There is urgent need for a new model to address the housing crisis in remote Australian Indigenous communities. Decades of major government expenditure have not significantly improved the endemic problems, which include homelessness, overcrowding, substandard dwellings, and unemployment. Between 2017–2020, Foundation for Indigenous Sustainable Health (FISH) worked with the remote Kimberley Aboriginal community, Bawoorrooga, by facilitating the co-design and co-build of a culturally and climatically appropriate home with community members. This housing model incorporates a program of education, health, governance, justice system programs, and land tenure reforms. Build features incorporate sustainable local/recycled materials and earth construction, and ‘Solar Passive Design’. The project faced challenges, including limited funding, extreme climate and remoteness, cultural barriers, and mental health issues. Nevertheless, the program was ultimately successful, producing a house which is culturally designed, climatically/thermally effective, comparatively cheap to build, and efficient to run. The project produced improvements in mental health, schooling outcomes, reduced youth incarceration, and other spheres of community development, including enterprise and community governance. Co-design and co-build projects are slower and more complex than the conventional model of external contracting, but the outcomes can be far superior across broad areas of social and emotional wellbeing, house quality and comfort, energy consumption, long-term maintenance, community physical and mental health, pride, and ownership. These factors are essential in breaking intergenerational cycles of poverty, trauma, and engagement with the justice system. This paper provides a narrative case study of the project and outlines the core principles applied and the lessons learned.

1. Introduction

Authors’ Note

- The authors have decided to use the first-person voice to allow for the narrative structure of the article and its presentation as a case study. It was considered that a depersonalised writing style would have made it difficult to adequately explain the process, particularly around the interpersonal, social, and cultural factors. Aboriginal culture is relationship oriented. Building interpersonal relationships will necessarily be at the core of any project that aims to work shoulder to shoulder with Aboriginal communities. The authors feel that understanding culture, building relationships, and incorporating community members at all stages is key in addressing the complexity of the challenges faced in Indigenous communities and that a more standard scientific language would detract from this concept and may encourage an unnecessarily prescriptive approach.

The Project

“It’s a fantastic idea! Of course you’ll still fail—because everyone fails—but the important thing is that you fail differently”. Those were Victor Hunter’s words—Nyikina elder and co-founder of Foundation for Indigenous Sustainable Health—when he invited us to trial a new housing approach in Australia’s remote Kimberley region. The comment reflects the entrenched normalcy of failure in remote Aboriginal housing, and the recognition that innovative approaches are critically needed.

There is an urgent need for a model of safe, secure, appropriate, and affordable housing for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people. This is a key social determinant of health and a fundamental building block for moving families out of poverty [1,2]. For decades, the United Nations has expressed dismay at Australia’s performance on Indigenous housing, with UN Special Rapporteur in 2006 describing conditions as being “amongst the worst … in the world” [3], and subsequent UN investigations in 2017 noting that few improvements had been made [4].

A recent study conducted by the Australian Housing and Urban Research Institute (AHURI) has found that regional and remote Aboriginal housing is unable to withstand climate change and will be unsuitable for future living [5]. Under existing models, remote Aboriginal housing is expensive to construct, expensive to run and maintain, climatically inappropriate, and quick to deteriorate [6,7]. Community members are seldom, if ever, involved in the design, construction, or maintenance of their homes, with the results being that the houses are culturally inappropriate, the residents have little sense of ownership or connection to their homes, and opportunities for vocational training in communities (construction and maintenance) are lost.

Foundation for Indigenous Sustainable Health (FISH) is a registered public benevolent institution and social enterprise working with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people to break intergenerational cycles of poverty, trauma, and engagement with the justice system. Commencing in 2017, FISH piloted a model which addresses the above shortcomings and serves as a prototype for sustainable remote Indigenous housing throughout Australia. The model is based on the following principles:

- Community co-design and co-build;

- Sustainable passive solar design suited to local climate;

- Use of earth (or other local, abundant material) as building material;

- Incorporation of education, community development, justice, and youth support.

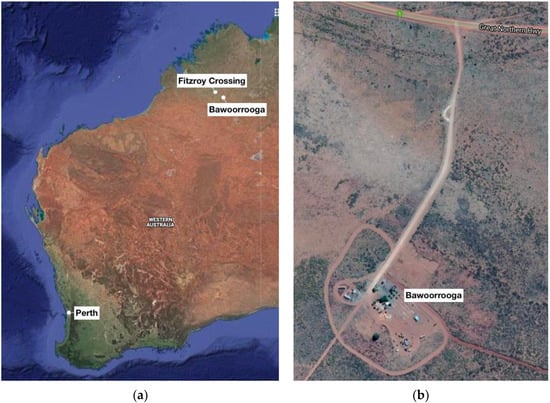

The pilot program was run as a partnership between FISH and Bawoorrooga Community (Figure 1) in the remote Kimberley, WA. The project has since been recognised for its contributions toward Indigenous advancement and the furtherance of the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals, including the United Nations Human Rights Award WA 2019 [8], as well as the Banksia Sustainability Awards 2019 (Finalist) [9], and publication in The Architect Magazine 2020 Edition, Australian Institute of Architects [10].

Figure 1.

Location Images (source: Google Maps): (a) Western Australia; (b) Bawoorrooga Community.

Contrary to the predictions of failure, the leader of Bawoorrooga Community ultimately gave the following assessment: “We’d like to thank everyone for helping us heal. All that [tragedy] is behind us now—we’re moving forward. We hope for this sort of project to happen in other communities that are battling like us… We’ve always got a big smile now—we’re happy. Before, it was really a downfall. Now, we feel our ‘lien’ (spirit) is going up and up as we build these walls. We feel ‘wideo’ (happy)—like your soul is really strong”.

2. Background and Setting: Bawoorrooga Community, East Kimberley

Kristian Rodd’s (author) career commenced in corporate law, before the search for greener pastures took him abroad to work with local communities in South America and Europe on grassroots natural building projects. Jara Romero (author) is an architect from Spain, who similarly shifted from the commercial realm to pursue sustainable development models. Both witnessed countless examples of community-driven self-empowerment through innovative natural building projects—treetop bamboo bungalows, colourful earthen desert retreats, living green roofs, snow-covered strawbale villas, hobbit homes—and it seemed evident that Australia could benefit from similar approaches [11].

In April 2017, we arrived in Fitzroy Crossing with the nebulous (and perhaps naïve) plan of undertaking a co-design and co-build natural construction project with a group of local people. Victor Hunter (FISH co-founder) introduced us to a local Gooniyandi (one of the East Kimberley language groups) elder—the manager of Mt Pierre cattle station. Victor explained to him that we were a mob from the east with skills and experience who had come to build houses with the communities and asked whether he might know of any local need for such a skillset. The manager pondered for a new moments before replying: “well that sink over there is in a pretty bad way—they could fix that”.

New-coming Kartiya (which means “whitefella” in Kimberley Kriol—the common “creole” language of the region) are often treated with suspicion and/or disinterest in remote Aboriginal regions. Many locals are tired of outsiders coming to their communities, full of promises and preconceptions, with little knowledge of the local circumstances and a tendency to talk more than to listen. Countless ambitious projects start, stall, and become abandoned midway—adding to the pile of ‘bridges to nowhere’. Some projects do reach completion, only to fade into oblivion shortly after their instigators leave the place. The term “plastic bags” is sometimes used, in reference to a white thing that blows in, floats around for a while, and finally blows away again.

Victor also told us about a small community called Bawoorrooga, situated on Gooniyandi land 100 km southeast of Fitzroy Crossing (Figure 1). It is slightly north of where the Great Sandy Desert transforms into what is known as the limestone country—an arid craggy landscape of cliffs and caves, the sharpness of which relates to its echidna/porcupine dreaming (the “dreaming” in Aboriginal philosophy is based on the inter-relation of all people and all things, including the creator spirit ancestors. This knowledge is handed down through stories, art, ceremony, and songs to explain the origin of the universe and the workings of nature and humanity). Bawoorrooga sits on a plateau of red pindan sand, scrub, and spinifex. The community was established in 1998 by community founders Claude Carter and Andrea Pindan (husband and wife) and their extended family. Since then, Bawoorrooga’s population has generally numbered around one or two dozen people—mostly members of the extended family. For years, the community has been a small hub of wholesome, self-driven initiatives, including traditional painting, horticulture (through a small orchard of mostly citrus and mangoes), culture, and spirituality. The community has long focused on supporting young people in need, through hosting school groups, as well as youth with troubled backgrounds or special needs. Due to its small size and, perhaps, the slow and mysterious machinations of bureaucracy in the remote regions, Bawoorrooga has never received any formal government housing. The buildings at the community were mostly sheet iron structures and spinifex bough sheds built by community members, except for one six-room donga (transportable) which was formerly part of a mining camp. The donga was provided to the community in 2004 through the local Aboriginal resource agency. Like much of life in the Kimberley, the ownership and ongoing maintenance responsibility of the donga were vested in an opaque space between the state government, the Aboriginal resource agency, and nobody (notwithstanding the fact that Claude, Andrea, and family paid years of rent to this amorphous proprietor). This was the legal no-man’s land of the Wild West. In early 2017, the community, on multiple occasions, reported an electrical fault in the donga, temporarily moving their beds into one of the iron sheds out of concern for their safety. Subsequently, the donga burned down, with most of the family’s belongings inside. When we first visited the community, Claude, Andrea, and family were living in a 5 m × 5 m sheet-iron shed. This was in a region where temperatures regularly exceed 45 degrees Celsius.

We knew little more than that about Claude, Andrea, and the Bawoorrooga Community on that first day when we met them and proposed to build a house with them. The community members knew as little about us when they excitedly agreed to the proposal.

3. Methods

3.1. Community Co-Design Process

In the weeks and months following our initial meeting, we regularly spent long periods sitting with the community members, residing for half of each week at Bawoorrooga—the other half was spent back at Fitzroy Crossing, camped on the banks of the Fitzroy River in our HiAce van. The purpose of our visits to the community was to get to know the family and to help them incrementally co-design their future house by understanding all the relevant factors: their priorities, values and cultural norms, desired living arrangements, available resources, available labour, local climate, etc. This process is described in the sections below.

3.1.1. Available Materials and Labour

Initially, our discussions centred around the available resources, namely what we would build with and who would build it. Apart from a few thousand dollars which had been crowd-funded for recovery in the wake of the donga fire, we had no money for the project. Thus, earth was an obvious candidate for the principle building material, being abundant, free, solid, termite unaffected, non-flammable, non-polluting, and highly suitable for the hot, arid climate of the East Kimberley. Earth has a high thermal mass, meaning that it has a high capacity to absorb, store, and release heat, taking a relatively long time to change temperature (thermal lag). This is beneficial in climates where there is a reasonable difference between day and night temperatures.

Research conducted by the University of Western Australia in collaboration with the Western Australian government Department of Communities recommended earth construction for remote community housing, noting that the “cost of construction in remote areas of Australia is extremely high due to the need to transport materials, manpower and equipment over long distances. Due to its use of local materials and labour, rammed earth construction offers a potential solution to this problem” [12].

Earth as a building material also greatly appealed to the community members for symbolic and spiritual reasons. To Bawoorrooga Community, the land holds a central place in cultural and spiritual identity. The land, the soil, the waterways, the plants, and the animals are not separate and distinct material objects, but rather, they are imbued with, and intermeshed by, one universal spiritual fabric. Many Aboriginal spiritual systems regard all objects as living and sharing the same soul or spirit [13]. Claude and Andrea described the idea of an earth house as “being in the womb of mother nature”—providing a physical connection to their country and to the countless generations of ancestors who also walked upon it.

Initially, given our lack of funding, our intention was to obtain most of the other materials through salvage and recycling. The frequent mismanagement of resources by agencies in remote areas often results in wastage and abandonment of materials, ripe for the picking. One local fondly referred to the rubbish tip as “Bunnings” (major Australian hardware store), for the range of useful materials one could find there. We could also recover good steel from the wreckage of the burned donga. Fortunately, we were able to forego some of these more desperate solutions when we later procured sources of project funding (see Section 4.1 below).

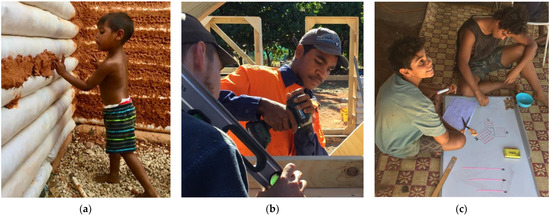

Using earth as a building material created a challenge: it is labour-intensive. Among the multitude of techniques typically used for building with earth, even mechanised methods such as rammed earth require significant labour. However, when posing this problem to the community members, their immediate response was: “she’ll be right—we’ve got a big mob family to help!”. The relative labour intensity of earth building can also be seen as a positive feature. One of the core benefits of the community co-build model is precisely that it requires a significant investment of time and energy by community members: the result being that everyone has “skin in the game”. It was important that the community personally invested—physically and emotionally—in the project, to create a sense of value, pride, and ownership amongst the participants. The final product then stands as a testament to the commitment, perseverance, and achievement of the team. Such personal connection to the house would be far less likely if it were constructed by outsiders.

Throughout most stages of the build, we typically aimed to have a working crew of around ten people (including the two of us), which would effectively allow for two supervised teams working simultaneously. The total number of participants throughout the project was around 30 people, excluding school groups.

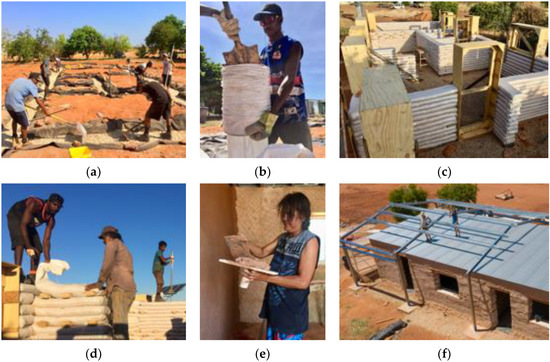

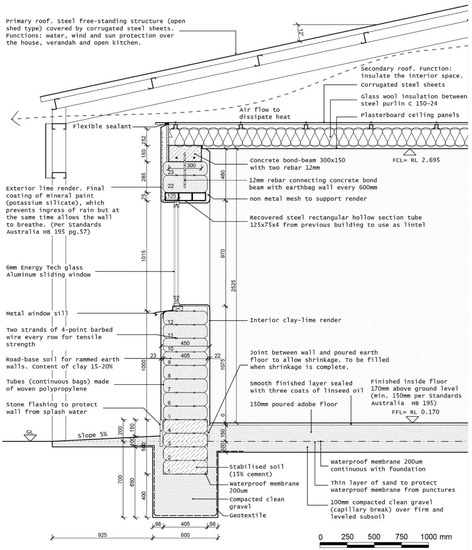

The chosen technique was a method known as SuperAdobe, or earthbag [14,15]. SuperAdobe is essentially a combination of rammed earth and sandbags. Walls are constructed by filling bags (or continuous tubing) with earth, typically with a clay content of around 15–30%, and tamping (ramming) the bags to compress them. Each row of bags is filled in situ on top of the previous, with barbed wire laid and compressed between each row. The strands of barbed wire bite into the bags, binding each layer and providing the whole structure with tensile strength against horizontal forces. The finished walls are then rendered (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Build method. Clockwise from top left: (a) gravel trenches; (b) bag filling; (c) door and window formwork; (d) aligning and tamping bags; (e) lime plastering; and (f) roof construction.

Additional advantages of SuperAdobe include its minimal equipment requirements, inexpensive ancillary materials (bags, wire, etc.), and ability to be built by a relatively unskilled workforce.

Although the region experiences seasonal flooding, the Bawoorrooga site is sufficiently elevated to avoid inundation. Protection from stormwater damage would be achieved by large roof overhangs, gravel trench foundations (“French drain” style), well-draining site soil, stone flashings at wall bases, and appropriate external render. The gravel trench foundations also had the additional benefit of not requiring concrete.

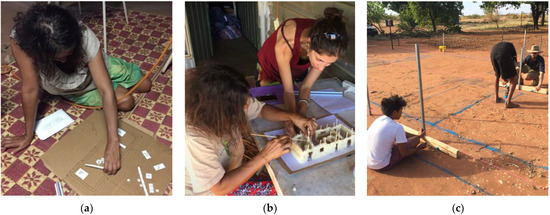

3.1.2. Design Stages and Modelling

The initial design began with two-dimensional cardboard models (Figure 3a): a base sheet to represent the space available, a series of movable walls, and a series of miscellaneous items such as beds and cupboards. The idea was to give the family a relatively blank canvass from which to originate ideas. The first design looked like a six-room donga—a straight row of five bedrooms and one kitchen. Jara guided this process, as most people (anywhere) will initially tend to replicate the models they have been exposed to. Exploring new design possibilities became easier by simply including cardboard tiles to represent people, which gave some perspective to how spacious or cramped a proposed layout might feel. Basic floorplans gradually took shape as the model facilitated dynamic and tactile discussions about how the spaces might be used, who would be using them, what a typical day might look like, etc. After each session, Jara would draft a few different iterations of the concept and return for continued yarning with the community.

Figure 3.

Design Stages: (a) 2-dimensional cardboard model; (b) 3-dimensional damper model; and (c) on-site line markings and walkthrough.

Once the community was comfortable with the basic design, we moved to three-dimensional modelling (Figure 3b). Our models were made from playdough (traditional damper and salt), which proved successful. This method provided a very simple, hands-on way of conceptualising the space and playing with the design. As well as enabling community members to easily imagine how the physical space would look and feel, the damper model also allowed us to demonstrate, in miniature, how the construction technique would work. The model was made by stacking layer upon layer of elongated dough worms—essentially mimicking the SuperAdobe walls. Some important insights came out of the 3D model stage. For example, it was only while making the model that Andrea noticed that the toilet door was internally accessible to the house. They had always been adamant that they wanted the toilet to be part of the house (i.e., not stand-alone)—for reasons of convenient proximity as well as the perception that it would feel more like a “proper house”. However, it was considered unhygienic to have access to the toilet from the interior part of the house. Therefore, the layout was switched, and the bathroom and toilet areas became outward facing. Referring to the “luxury” of ensuites, one elder explained it like this: “Kartiya houses are mad—the folks crap right next to where they sleep!” This was one of the many moments throughout the design (and build) process where cultural norms or community preferences introduced design features significantly different from mainstream Australian house design.

The final design stage was the on-site line markings and walkthrough (Figure 3c). As well as yielding some small alterations to the orientation and placement of the house, this step was also critical to the core principle of co-design; it re-emphasised that ultimately the community—not the outsiders—were responsible for, and in control of, the outcomes of the project. Furthermore, it provided an opportunity to incorporate training around measurement, geometry, mathematics, etc., linked to real-world applications.

3.2. Commencement with FISH: Foundation for Indigenous Sustainable Health

We had been working with Bawoorrooga Community for several months, developing the design, planning the program and build process, and seeking funding. Funding was proving difficult, given that we were not associated with any organisation through which to apply for grants. We contacted FISH to ask whether they might be able to back the project so that we could apply for funding under their auspices.

FISH had recently employed a new CEO, Mark Anderson, with 30 years of experience in Aboriginal and community development and an exceptional drive to bring about structural reform. After several meetings, it was clear that our proposal aligned with FISH’s strategic goals and values—our project outline almost perfectly mirrored FISH’s own policy document on proposed remote housing. It was decided that FISH would employ us to deliver the project—Kristian as project manager and Jara as architect and project coordinator. This did not immediately remedy the problem of funding as FISH at that point did not have available funds, but it provided a base of organisational legitimacy as well as support in the form of professional knowledge and mentoring.

Having officially become a FISH–Bawoorrooga project, it was vital to ensure that the final house could be held out broadly as a viable, replicable, and appealing model, rather than simply a one-off emergency solution. We made some changes—deciding to purchase, rather than salvage, certain items, including doors, windows, roofing, fixtures, etc., while retaining the ethos of reuse and recycling wherever possible. The building was designed in accordance with the best practice guidelines contained in Standards Australia’s The Australian Earth Building Handbook [16] and was also certified by a structural engineer as being complaint with other relevant Australian Standards, including AS/NZS 1170.0:2002 Structural Design Actions. We obtained surveyor-certified energy ratings and other documents necessary for the Certificate of Design Compliance, through which we then obtained a building permit from the Shire of Halls Creek.

3.3. The Build Process

Virtually every stage of the build, from foundations to finishes, was done by or with the participation of the community members, with only a couple of specialised tasks requiring a licenced tradesperson—electrical installation and plumbing—completed by local contractors. As much as possible, we attempted to engage Aboriginal owned, or staffed, businesses in any contracting and supply.

We settled on a working week of 3.5 days—from Tuesday midday to Friday afternoon, with a typical team size of between 5–10 people. The workers were predominantly extended family members, males aged early teens to early twenties, and Claude and Andrea—the future owners of the house. As the workers were community members constructing their own home, the work was on a purely voluntary basis. For those receiving Centrelink payments (Australian government services and welfare agency), participation counted towards their obligatory Community Development Program hours (“work for the dole”). Generally, we were only successful in recruiting workers from within Claude and Andrea’s extended family. We initially commenced at 4.5 days/week; however, trying to maintain this rhythm imposed a strain on the community members which ultimately proved counterproductive. There were a few relevant factors limiting our working week:

- The work was often physically taxing and done in extreme heat (up to 45 degrees Celsius).

- Throughout the entire duration of the project, the community lacked adequate accommodation—comprising only sheet-iron sheds and caravans. The abject poverty in which we and our workers resided was a major source of physical and psychological stress, reducing the workers’ capacity to engage. This also sat in the traumatic context of recently losing their home and belongings to fire.

- Claude and Andrea were responsible for feeding and housing the workers during the week, and often lacked money to purchase food or the means to make the 200 km round trip to the Fitzroy Crossing supermarket.

- In most of the Kimberley, physical and mental health issues are prevalent, commonly stemming from intergenerational trauma and the persistent legacy of colonisation. This hugely impedes normal, day-to-day functioning in these communities.

- Unemployment rates in the remote Kimberley are amongst the highest in Australia, with the majority of many communities being unemployed. Many members of our team had no prior working experience, and the project was their first introduction to daily routine, timetabling, and other norms common to workplaces.

Our workload intensity needed to balance all these factors or risk losing engagement. Despite the impediments, we formed an effective team. Community members were very excited to be doing something which no other Kimberley community had the opportunity to do—design and build their own house. Construction of the earth walls commenced in March 2018 and took approximately four months to reach full height.

The working days commenced around 8 am, breaking for lunch at 11 am. For much of the year, the lunchbreak would include a trip to the local waterhole, a fun opportunity to escape the extreme midday heat and an invaluable incentive/reward to the team for their morning’s work. A motivator such as this is almost indispensable to any project involving a young, volunteer workforce, as team morale is often the most challenging and fluctuating variable. Work would then resume at 2–3 pm, finishing around 5–6 pm (an approx. 6 h working day). We completed the house in April 2020.

The construction tasks completed with and/or by the community team included demolition of the fire wreckage; site levelling, squaring, and compaction; soil testing; earthworks and heavy machinery operation; foundation laying (rubble trench); wall construction; timber formwork construction (doors/windows); door and window installation; ceiling installation; rendering/plastering; earth floor installation and sealing; paving, tiling, and stone masonry; concrete beam pour; roof construction; electrical and plumbing pre-lay; painting and waterproofing; and welding, cutting, and grinding.

4. Challenges

4.1. Resources and Funding

Obtaining the required funds was a major impediment throughout the duration of the project. As mentioned above, at the project’s inception we had only a few thousand dollars and were planning to construct with free or extremely low-cost materials. As the project evolved, now as a FISH initiative, it was necessary to revise the budget and obtain a source of funding. Significant funding sources for alternative, grassroots models of remote housing and community development are not readily available, and our proposal would have looked like a high-risk investment. There were virtually no recent examples of similar initiatives in Australia, and an entrenched attitude of cynicism existed around expenditure in remote regions, namely that tremendous amounts have been spent by governments over many decades with very little improvement to the economic, social, and emotional wellbeing of Aboriginal people in these regions. Despite the very apparent need for new models of housing, funding is seldom given to proposals without a track record. Credible research, including the governments’ own research, has for years been calling on governments to change their approach [5,7,12,17]. Instead, money continues to go to providers with a track record of poor results. We faced a chicken-and-egg dilemma—we could not get funding for an unproven model, and we could not prove our model without funding.

We obtained funding through a piecemeal collection of sources, including philanthropic donations, private and government grants, Bawoorrooga Community enterprise (e.g., sale of artwork at exhibitions in Perth organised by FISH), volunteer collaboration, pro bono services, and revenue from other FISH initiatives. The timing of the funds was unpredictable, and obtaining the next tranche was never assured. This led to delays and inefficiencies in the project, as well as a heightening of the stress amongst community members and us, which also impacted the effectiveness of the program. The sustained poverty endured by the community members throughout the entire build would be considered almost inconceivable in any other part of the developed world. Consequently, the project was halted several times for weeks or months because of funding delays. This was a foreseeable vulnerability from the outset. However, if we had insisted on eliminating this risk entirely, we would likely have never started.

4.2. Climate and Remoteness

For around four months of each year (around Nov–Feb), maximum temperatures in the region regularly exceed 45 degrees Celsius. At these temperatures, outdoor physical labour is practically impossible. The wet season also experiences regular flooding, during which the Great Northern Highway—the only sealed access road across the region (and to the community)—is regularly cut off for days or weeks at a time. Accordingly, work at Bawoorrooga would cease for 2–3 months and resume after the wet season.

Even outside these extreme periods, working times had to be paired with the realities of the weather—extreme heat, wildfires, rain, or wind. At one point, the community was gifted a light transportable donga to help alleviate the accommodation shortage for the workers. One night, seven members of the working team (including Claude and Andrea—the community leaders) were inside the donga when it was struck by a “willy-willy” (small tornado). The building was lifted off the ground and thrown 50 m, finally coming to rest as a pile of shredded debris. During the same incident, the community’s two-tonne tractor was flipped upside down and a concrete slab was torn out of the ground, while light caravans mere meters away remained in their positions unscathed. Incredibly, none of the occupants were killed, however all ended up in hospital for treatment of various injuries. Their recovery—the physical and mental trauma of the incident—ranged between weeks and months and was a setback to the community and the project.

The tyranny of distance is another reality of life and work in the Kimberley. Bawoorrooga is more than 2500 km from Perth, 500 km from Broome, and 100 km from Fitzroy Crossing. Procuring tools, materials, or even food required advance planning as mistakes, breakages, or omissions could take weeks to rectify. Some of our team normally resided in Fitzroy or other communities, which meant that they had to be driven out for the week and returned home for the weekends. On the one hand, this created a weekly logistical challenge in locating and transporting the workers. On the other hand, once they were at the community, we had the certainty that they would be at the worksite with us until the end of the week.

4.3. Cultural and Social

Kristian is non-Indigenous Australian, and Jara is Spanish (now also Australian). We have both lived and worked in many countries throughout the world, immersing as much as possible within a diverse range of cultures. We have never encountered a culture more distinctly different from that in which we were raised than the society we found in the Kimberley. Amazingly, this society exists within the borders of our own country. Before our journey into remote Australia, we had done our best to understand this nation’s Indigenous history: how the land and its people had been prior to European arrival, the devastating story of conquest and colonisation, and the remarkable survival and continuation of the resilient cultures we see today. Nonetheless, when we arrived in the Kimberley, we had very little understanding of its culture(s) and people, their values, norms, experiences, assumptions, and styles of communication. Without an extended period living within a society, it is very difficult to understand these things. Even after three years of immersion, we were only beginning to understand the Kimberley peoples’ view of the world and their different approaches to relationships and obligations, to time, scheduling, and planning, to the human connection to land, to the concept of wealth, ownership, and resources, to history, and to the material and metaphysical worlds. This essay is not an exploration of these differences—we simply note that on every one of these points, the attitudes and beliefs we found were unfamiliar and often unexpected.

Nonetheless, we found much common ground—such as the importance of family—on which it was relatively easy to connect. We learned a lot from their many strengths—about observation and listening, about land and country, and about community. Our time at Bawoorrooga gave us a glimpse of the values, wisdom, and ingenuity of a culture which has survived and thrived on this continent for more than sixty thousand years.

4.3.1. Time and Budgets

In the Kimberley, there is no rush. The people have always been there, and they will continue to be there long into the future. The world carries on in cycles—long periods pass silently and patiently, with little activity. Suddenly, life is rocked by frenetic bursts of activity and change. The pace of life is not like it is in the cities. In Claude’s words: “We Kimberley people don’t keep diaries”.

From a project management perspective, this created major challenges. Our budget was always extremely limited, and delays simply ate up scarce funds. Furthermore, outside of Bawoorrooga, we did not have alternative projects to pivot to when progress was impeded. These were existential threats to the project, but they never translated into a real sense of urgency in the community. Deadlines and scheduling are simply not given the same emphasis that we Kartiya are seen to give them. However, on a few occasions the imminent changing of the seasons did act as the spur we needed. For example, the knowledge of the impending wet season made it critical that we completed the roof and render before the rain. The team summoned a huge show of force, completing the works mere hours before the heavens opened, with the deluge seen as a celebratory gesture from the country. The weather and seasons have always dictated the shape and pace of life for the people out there.

Our project was always a meeting of two worlds—each with different values and priorities. The “Western” world, where everything is measured in time and money, is always running, competing, catching up, perpetually stressed, and in a hurry. Living in this way requires a certain mindset which often holds little appeal for people from different value systems. For Bawoorrooga Community, despite their critical need for housing, there were things equally as important as building the house—cultural customs, visiting and hosting family, “sorry business” (funeral) traditions, rest and recuperation, hunting and fishing, yarning, and spiritual observance. Our solution to this was to keep the scope broad and flexible. The project was not simply about building a house—it was a program of community development, horticulture, education, health, and wellbeing. Because our program was multi-purposed, we were able to pivot and adapt our activities to changing circumstances, delivering a benefit even when the build was slowed or halted.

Communication around money and budgets was also an ongoing challenge. Chronic poverty in the Kimberley meant that money could quickly become an intensely emotional topic and one which community members expected to be kept abreast of. However, to complicate this, numeracy and financial literacy were very limited, and these discussions were ripe territory for misunderstanding and tension.

An important tool in dealing with these challenges was through regular yarning circles. Each day would begin with a quick check-in and stretching, which helped to motivate the team and gauge any concerns. Each week finished with a group meeting, to reflect on achievements and challenges. Private check-ins with Claude and Andrea were also very important, as was the skill of “reading between the lines”, as indirect communication was often the culturally preferred way of dealing with sensitive issues.

4.3.2. Trust and Exploitation

The relationship between blackfellas and whitefellas in the Kimberley is sensitive and complex. European colonisation, which in practically every region involved unspeakable violence, deceit, and exploitation of the Indigenous people, has left a legacy which continues today as direct, and intergenerational, trauma. Many Kimberley people still alive today have memories of atrocities, not to mention the racial prejudice and structural inequality that currently exists in much of Australia. It is therefore not hard to understand why trust towards newcomer whitefellas must be hard earned and why resentments still simmer. It was only after 12 months of living with the community that some of the elders finally addressed us directly. Even after construction had thoroughly begun, there was a suspicion among community members that we would leave and simply not return.

Additionally, generations of oppressive and paternalistic government policies have stripped many Aboriginal people of autonomy and agency. Welfare dependency has become prevalent in many communities, further diminishing responsibility and accountability. The welfare and service industry in the remote regions is pervasive, in some cases nearly severing the psychological link between action and consequence for many of its “beneficiaries”. In some communities, poverty, youth crime, substance abuse, and unemployment, are normalised. There are many complex reasons for this, and our experiences in the Kimberley do not qualify us to provide a comprehensive explanation but, rather, to simply comment on what we observed.

During much of our time at Bawoorrooga, we were viewed as coming there with an obligation to provide rather than with an offer to facilitate. We saw that community members would identify as recipients, rather than as agents of their own outcomes. Whenever this attitude surfaced, it typically resulted in either inaction, or actions designed to extract an immediate short-term handout, often at the expense of the collaborative approach we were trying to foster. This mindset, combined with a residing mistrust, meant that we were sometimes suspected of corruptly benefiting from the project. Our resourcing challenges actually meant that the opposite was true, with us volunteering during periods of the project; however, it was not always easy to allay these suspicions. This obstacle gradually abated over time, with the community becoming more engaged and responsive as they saw progress and results.

There were times when we met with challenging behaviour, either interpersonal or project related, and had limited options of redress. We (and FISH) had committed to sticking with the project until completion, notwithstanding the constraints of budget and time. Although this commitment was necessary for creating continuity, trust, and certainty in the project, it also made it harder to generate a sense of total responsibility and accountability amongst the community because we had created the perception that we would push the project forward, no matter what.

As the community members later acknowledged, these mindsets had been a major impediment to the idea of self-empowerment. As explained further in the sections below, an essential part of the project involved the participants shifting their own mindset to one of personal agency, which then allowed them to flourish.

4.3.3. Gender

The culture in much of the Kimberley typically maintains a strict consciousness of gender differences and divisions. This was evident throughout the project, including the design stage. This meant that:

- Tasks and roles were typically assigned to genders. For example, women made most of the design decisions. Except for Jara and Andrea, men and boys did most of the building, and it was difficult to engage other women to participate in these tasks.

- People preferred direct communication with members of the same gender and generally avoided being alone with members of the opposite gender.

It was fortunate that we were a male/female team, as we commonly encountered situations which required one or the other of us for reasons of gender. For example, much of the community’s valuable input would likely have been withheld were it not for Jara’s rapport with the women.

4.4. Mental and Physical Health

The challenges discussed above regarding trust, cultural differences, communication styles, and other stressors were exacerbated by a range of mental and physical health problems pervasive in the region.

Fortunately, alcohol was non-existent at Bawoorrooga thanks to a decision by community leaders to ban it years ago. When other addiction and substance-related issues arose, we observed that the most effective form of management was through the leadership of the community elders and role models and by alleviating the general community stress factors.

Our team was frequently affected by the tragic events of the broader Fitzroy Valley. Suicide is an ever-present reality of the region, with self-harm and suicide rates amongst the highest in the world [18]. No community in the region is immune from the effects of this. These events reflect the tragic prevalence of depression, anxiety, PTSD (post-traumatic stress disorder), FASD (foetal alcohol syndrome disorder), and substance addiction in the region. Simply living in an environment surrounded by these problems has a long-term corrosive and traumatising effect on people.

These cumulative stresses periodically reached tipping points where team cohesion would break down and progress would halt. If one or more members of our working team were unable to participate, we would generally find ways to adapt, with others stepping into the working role while the affected person(s) could receive support. The situation was more complicated when it affected the community leadership because there was no one else who could take on the same role. Due to Bawoorrooga’s small population, no one else had Claude’s leadership authority or his capacity to motivate the team. Most of the workers were Claude’s direct family and looked to him as the community, cultural, and spiritual leader. When Claude was overburdened, the project could easily stall. Aside from his responsibilities to the build, Claude had numerous other competing roles and duties, including serving as the Chair of the Gooniyandi Native Title organisation and supporting a large network of family members. With Claude as the sole leader, in this sense we had all our eggs in one basket, a vulnerability for which no simple solution existed. This came down to a question of relationship management. With real concerns about budget and time, it was very difficult to convey a sense of impetus without triggering a sense of overwhelming pressure on Claude. Furthermore, our being outsiders to the community, non-Indigenous, significantly younger (early thirties), and (for Jara) female—these were all relevant factors in our delicate negotiations through times of stress. One thing we lacked was a senior local person able to lend a respected voice to the conversation when issues arose. On occasions, more senior members of FISH were able to play a key role in fostering solutions.

Physical health problems are also tragically prevalent in WA and the Kimberley. Indigenous West Australians have a life expectancy around 12–14 years less than non-Indigenous Australians [19]. The rate of avoidable death is 4.9 times higher than that of non-Indigenous people [19]. Indigenous Australians are 20 times more likely to be hospitalised for renal dialysis [19]. Illnesses such as rheumatic heart disease—considered eradicated in the developed world—remain prevalent in the Kimberley. Members of our team were frequently affected by a range of health complaints, further adding to the suite of challenges above.

4.5. Land Tenure

Practically all the Kimberley is Commonwealth Crown land, meaning that for most Aboriginal people in the region it is impossible to own a freehold title to their house or land. Almost all communities are situated on some form of long-term lease-holding, often held by the WA Aboriginal Lands Trust (ALT), and the houses are owned by the Department of Communities (formerly Department of Housing). To further complicate matters, many communities also form part of a pastoral lease, and most are also part of native title determinations. Each of these many stakeholders has a seat at this crowded table, creating a diffuse ownership and decision-making structure over which community members themselves have very little control. If a person wants to build and own a house at their community, the legal and administrative process is so complex that they are practically precluded from it. Bawoorrooga’s quest to obtain meaningful land tenure commenced around more than a decade ago. The process was again re-commenced in 2017 with the support of FISH and is still currently ongoing.

Lacking meaningful tenure not only denies individuals and communities a legal basis for erecting a home, but it also often denies them the financial avenues available to many other Australians. For example, lacking land tenure precludes eligibility for the First Home Owner Grant schemes, as well as other financing options such as IBA (Indigenous Business Australia) home loans.

4.6. COVID-19

Finally, the global emergence of COVID-19 resulted in delays and difficulties in the final stages of the project, with several months of lockdown in early 2020. Throughout the pandemic, the Kimberley has been among Australia’s least vaccinated and most vulnerable regions.

5. Outcomes

5.1. Culturally Appropriate House

“That FISH mob—they’re the first people who ever really asked us what we wanted. They really sat down and designed it together with us. That design—it was the right one. It’s like they’ve lived with us for ten years!”

Conventional remote housing design rarely reflects the characteristics of the local cultures and their unique lifestyles [7]. This not only deprives houses of a sense of appeal to their occupants, but also of practicality. Kitchens are designed without regard for typical food preparation customs, floorplans do not facilitate cultural relationship structures, such as “avoidance relationships” or separation of genders, and temperature control systems assume that the occupants—typically outdoor people—are happy to live inside poorly-lit, hermetically sealed environments. Through his work with Indigenous co-design and co-build in the Torres Straits, architect Paul Haar noted that “we must have faith in and make real space for the creativity and lifestyle aspirations of dynamic communities of Indigenous Australians. They are not needy subjects of White benevolence but equal partners in the challenging times we have ahead” [20].

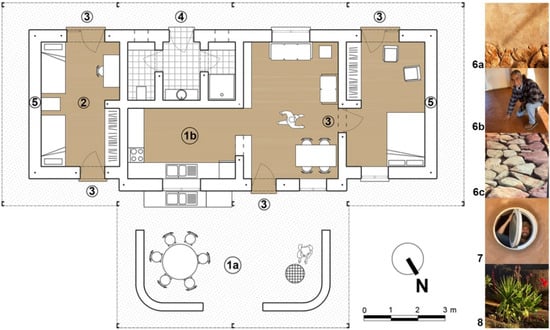

The Bawoorrooga house is a true reflection of the people who live within it—capturing their spiritual, aesthetic, and practical needs. Most of these design features are extraordinarily simple but have only arisen because of the co-design process. Figure 4 explains some of these features:

Figure 4.

Community design features.

- The house contains (a) an outdoor and (b) an indoor kitchen area. The house, like many Kimberley houses, will be visited and used by a cast of thousands. Extended families are large, visits are frequent, the movement of people is fluid throughout the region. The indoor kitchen is intended exclusively for the occupants and is positioned to minimise foot traffic and enable Andrea to maintain a level of order and control over the space. The outdoor kitchen serves as the common area, accessible and usable by all comers. It contains a cooking firepit, a seating space, a storage space, and a washing area. The area is well shaded and shielded from the wind. Freshly hunted meat or fish is a common part of the Kimberley diet, the preparation of which is unavoidably messy. The area can be easily cleaned with a mop or hosed down.

- The house contains a bedroom which is not communicated with the other internal spaces of the house. The intention is that this space enjoys relative separation and independence—often important in the cultural relationship dynamics of the family.

- The house has an abundance of doors. Every space of the house provides two exits. This was important for the family to avoid feeling trapped. Particularly in the context of the trauma of the previous housefire, this was a relevant consideration.

- The toilet and bathroom are communicated only with the rear outside of the house—a preference relating to hygiene. The numerous visitors to the house are typically expected to use the separate ablution facilities located within close walking distance of the common area.

- Thick earthen walls provide excellent sound insulation [21]. This provides greater privacy and tranquility in the often lively tumult of community living.

- The walls and floors are made from earth ((a) the walls are lime rendered and (b) the floors are burnished and wax sealed), holding spiritual and symbolic importance. The outdoor floors are paved with flat river stones collected from traditional Gooniyandi hunting grounds (c). Claude talks about how the house contains the spirit of his ancestors, as well as a piece of every person who helped in the construction.

- The windows of the wet areas (bathroom and toilet) are circular. This shape represents the traditional symbol for the sacred “jilas” (waterholes) New visitors to the house are always taken to look at these windows when they are given the tour.

- Bawoorrooga is a community of artists, who love painting designs on their walls and tiles. The community also established a vibrant garden around the building, adding to the beauty of the place and providing modest additional cooling and shading.

These cultural, personal, and practical features of the Bawoorrooga house are what transform it into a home. This is Claude’s description of his house: “My house is alive, just like a person—it’s breathing. It’s made from Mother Earth, Gooniyandi country. In the daytime, it keeps you cool, and at night time it keeps you warm”. Figure 5 shows the finished house.

Figure 5.

House at completion.

5.2. Climatically Superior House

The dominant construction technique in remote Australian communities is the steel framed house [6]. Many of these houses lack even basic climate-informed design features such as wrap-around verandas, double glazed windows, or adequate insulation [5]. In the extreme heat of these regions, the habitability of these homes relies on the constant operation of air-conditioners. If the air-conditioners fail and are not promptly repaired (at great cost) or if residents cannot afford the ongoing running costs of electricity, the houses risk being abandoned and further deteriorating—a common scenario [12]. Furthermore, most electricity consumed in Kimberley communities is generated via diesel generators, which is financially and environmentally unsustainable. During our years in the Kimberley, it was common to see residents drag their beds outside to sleep at night due to the intolerable heat inside the houses. Likewise, we saw countless houses where reverse cycle air-conditioners had been haphazardly installed in window openings—a grossly inefficient solution which also deprived the rooms of natural light.

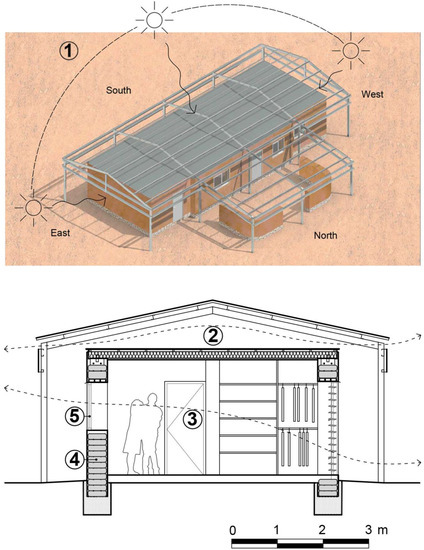

The Bawoorrooga house does not contain, nor does it require, an air-conditioner. This is because it utilises passive solar design principles. “Passive design” or “passive solar design” is a broad set of principles around working with the local climate to maintain a comfortable temperature in the home, reducing or eliminating the need for additional heating or cooling. Building features such as orientation, thermal mass, insulation, and glazing work together to take advantage of natural sources of heating and cooling, such as sun and breezes, and to minimise unwanted heat gain and loss [22]. At the date of writing, the house has been occupied for one wet season (summer) and two dry seasons. The residents of the house consistently report absolute satisfaction with the house, including its thermal comfort, noting that it mitigates the extremes of both hot and cold. FISH is in the process of arranging a formal study involving placement of temperature sensors in and around the house to assess its thermal performance. The key features of the house are outlined below and in Figure 6 and a detailed construction section is shown at Figure 7:

Figure 6.

Passive Solar Design features in the Bawoorrooga house.

Figure 7.

Detailed construction section.

- Orientation and shape: The house mimics the shape of northern Australia’s magnetic termite mounds. They are long and thin, running east to west. When the sun is at its highest (and hottest), during summer and in the middle of the day, the roof provides complete shade. In early morning (east) and late afternoon (west), the sun is lower and so the roof provides less shade. Accordingly, the eastern and western sides of the house are narrow and do not contain openings, greatly reducing radiant heat absorption.

- Ventilated double roof: The house has a free-standing, white tropical roof with large eaves, shading the house like a giant umbrella, and a flat insulated roof underneath. This creates a simple double roof structure, allowing air to pass freely through the space between, dissipating the sun’s heat. It is far more efficient to stop heat from entering the house than having to remove heat from the inside.

- Air-movement: All rooms have opposite openings for cross-ventilation and a ceiling fan. This prevents the build-up of pockets of hot air and enables people’s bodies to naturally cool through the evaporation of sweat.

- Thermal mass: Thermal mass is the ability of a material to absorb, store, and release heat. High thermal mass materials, such as earth, have high thermal lag, meaning they change temperature very slowly. This is beneficial in climates where there is a reasonable temperature difference between day and night because it keeps temperatures closer to the average rather than rising and falling with the extremes. Meteorological data from nearby Halls Creek show that the temperatures can range between approximately 16 to 45 °C in January, and around 1 to 34 °C in July [23].

- Appropriate glazing: Double glazing or laminated windows reduce heat conduction through the glass and minimise radiant heat gain.

5.3. Lower Cost

Currently, remote housing is extremely expensive to construct. Industry cost guides estimate remote housing construction costs are at least double those of non-remote locations [24]. Operating and maintenance costs are three times greater for remote housing than in capital cities [5]. Compared with conventional models of remote housing delivery, construction costs under the Bawoorrooga-style model are significantly reduced because:

- The principal building material is locally sourced earth which, aside from excavation costs, is free;

- Most of the workforce are volunteers, who directly benefit from the project through the use or ownership of the finished house or through participation in the various programs linked with the project (education, training, youth support, justice, etc.).

Ongoing running costs are significantly reduced compared with conventional remote housing. Electricity consumption is drastically reduced due to the thermal efficiency of the house design, eliminating a huge portion of the typical ongoing running costs. Even where solar power is used (as in Bawoorrooga’s case) efficient buildings require far smaller systems (panels, inverters, batteries, etc.), thereby saving a massive cost.

Finally, repair and maintenance expenses can be significantly reduced. The maintenance of conventional remote housing is a major ongoing cost to governments. Expensive contractor services and huge travel times make existing service models financially unsustainable, often with the result that repair and maintenance are limited to emergency works only [25]. The FISH–Bawoorrooga model can significantly reduce these costs because:

- Through the process of constructing the house, community members acquire many of the skills later required for routine maintenance, particularly if this is actively included as a training component of the build program. In Claude’s words: “We built it—we know how to fix it”.

- The importance of ownership and responsibility that comes with constructing one’s own house is impossible to overstate. Bawoorrooga Community members have a great psychological investment in the house. It is a source of pride and an expression of self, which generates far greater motivation to proactively maintain it.

- As discussed above, poorly performing houses, including houses with culturally inappropriate design, are often either abandoned or used in a way which accelerates their deterioration. Sensible design, adapted to climate and local living practices, means a house is more likely to be used as intended and, thus, endure for longer.

As part of FISH’s formal handover of the finished earth house to Bawoorrooga, the community members signed a rotational long-term maintenance schedule. This document, which was developed with the community members and was graphically designed to suit the specific numeracy and literacy skills, outlines the routine inspection and maintenance tasks that must be periodically undertaken. These tasks include checking things such as water leaks, damage to walls, flooring, doors and windows, smoke alarms and the condition of the electrical fittings, the condition of the seals and grouting, pest infestations, and general cleaning. The community members clearly understand and accept these responsibilities, including the implication that neither the government nor any other third party has any obligation to maintain their house. As the house is legally owned by Bawoorrooga Community Inc (the community’s Unincorporated Association), FISH supported Claude and Andrea in setting up a system which enables them to pay rent into a community bank account to build a fund dedicated to house maintenance, as well as house insurance.

5.4. Community Pride

From the earlier discussion of mental health and suicide, it is evident that community pride is an indispensable pillar of any sustainable community, without which all other development programs—housing, public health, education, crime prevention, and employment—are far less likely to succeed [7]. To achieve lasting change, people need a hand up—not a handout.

Building their own house—through hard work, determination, time, and energy—was a remarkable achievement for the community. Their home stands as a permanent testament and daily reminder of their accomplishment—a major contributor to their mental health. A community with a sense of self-worth and personal agency is far more capable of embracing education and employment opportunities, achieving economic self-sufficiency, sustaining culture and traditions, responsibly parenting children, minimising substance abuse, maintaining law and order, and taking care of their surroundings [2].

The physical and social environment of the home are fundamental to the social fabric of communities and families. As Claude notes of his own community: “We feel proud of what we’ve done. Respect, discipline, duty—they come from the home. When we’ve got a home, we can make our kids healthy. While we’re up here on our homeland we can control things like diabetes. We go out fishing, hunting, eating bush food, cleaning up—we’re always active”.

Figure 8 shows part of the Bawoorrooga team, with Kristian, Jara, Andrea, Claude, and other team members in order from the left.

Figure 8.

Part of the Bawoorrooga team during the build.

5.5. Education and Training

We incorporated education and training into each stage of the project, with a focus on developing practical and vocational skills as well as basic literacy and numeracy. We were approached by the Fitzroy Valley District High School after teachers noted dramatic improvements in classroom behaviour amongst some of the students who were regularly involved in the project. Subsequently, we partnered with the school to establish a credit-recognition arrangement whereby students’ participation in the project was credited towards their formal education. The project was designed with an understanding that many people in the Fitzroy Valley have little formal education and varying levels of English comprehension, literacy, and numeracy. Speaking about a participating student, the Senior School Advisor remarked: “He has become more mature, sensible and now he likes learning. He is learning in a real sense about measurement, angles, and about tools, he’s learning to work with people, he’s learning to work in a responsible and safe way, and above all, he’s contributing to the benefit of his community”.

We regularly hosted class visits to the site, incorporating the nationwide “Big Picture Education” program into the activities provided to the students [26]. Under this individualised “interest-based learning” approach, the curriculum was woven into practical projects chosen by the students according to their interests. For example, the participating students grasped the application of the Pythagorean theorem through our on-site squaring of the house foundations.

The project also engaged community members of all ages. The involvement of children allowed them to observe and work alongside their parents and role models, instilling positive values and behaviours in the younger generation.

As shown previously in Figure 2, the project provided exposure to a comprehensive range of practical construction tasks (Figure 9). Through discussions with the local TAFE (Technical and Further Education institution) and other registered training organisations, we attempted to offer the program as certified vocational training; however, we were ultimately delayed in this by administrative hurdles. Nonetheless, the content of the experience was invaluable for the participants. Marra Worra Worra Aboriginal Resource Agency facilitated the project’s inclusion as a Centrelink CDP project, enabling participants to satisfy their obligations to Centrelink through the build. Marra Worra Worra’s Director of CDP at the time remarked: “In more than 30 years [we have] not seen a more engaging, exciting, and relevant project. It is the immeasurable emotional difference that comes … from local Indigenous achievement that is almost beyond description”.

Figure 9.

(a) Participation by all ages; (b) practical vocational training; (c) maths and angles class.

5.6. Justice

In 2019, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander adults were imprisoned at twelve times the rate of non-Indigenous adults [27]. The WA Department of Justice statistics demonstrate how over-represented Aboriginal people are in the adult justice system, comprising 40% of the prison population while making up only 4% of the general population [28]. Juvenile justice is even worse, with Aboriginal people comprising around 75% of detainees [29].

Throughout the project, we often worked with the Department of Justice. In one instance, a young man on remand was allowed to reside at Bawoorrooga and participate in the project as an alternative to incarceration pending his hearing. On another occasion, a magistrate made a similar order in sentencing, noting that but for the FISH–Bawoorrooga project she would have been compelled to impose a custodial sentence. In each instance, the court’s decision was an express recognition that the project and the community offered a safe and productive alternative to incarceration, which benefited the participant and the community alike.

Additionally, the project was registered with the Department of Justice as a community service order host, giving people the option of participating as a means of complying with any court-ordered community service obligations.

The community also received a grant from the WA police force to establish a short-term horticulture program for young people. The purpose of these grants is to engage troubled youth in enjoyable and meaningful activities to provide positive direction and diversion from antisocial activities. This program was integrated within the existing horticultural activities at Bawoorrooga.

5.7. Broader Community Development

Concurrently with the construction of the house, FISH ran (and continues to run) multiple other activities at Bawoorrooga, including establishing an orchard to build upon the community’s existing passion for plant cultivation. The orchard, which includes more than 30 species of fruits and edible plants, was part of a broader enterprise and community development program at Bawoorrooga, also developed through co-design with community members, and which is ongoing at the date of writing. Other components of this program currently underway include the establishment of a workers’ camp to house 26 people and an enterprise centre—from which the community can provide goods and services to members of the public, including art and cultural crafts, orchard and market garden produce, cultural tourism, and (in the longer term) tourist accommodation. Bawoorrooga is opportunely situated right next to the Ngumpan Cliffs tourist lookout on the Great Northern Highway—a prime location to take advantage of the constant flow of tourists during the dry season. The workers’ camp and enterprise centre will comprise repurposed transportable buildings donated by the Argyle diamond mine during decommissioning, which will be transformed into quality living spaces through the integration of the passive solar design techniques discussed above (e.g., rammed earth elements, tropical roof structures, etc.). These facilities have also been co-designed with community members. To date, the buildings have been delivered to the site and secured to footings, and septic systems have been installed with the next stages due to commence following the relaxation of COVID-19 restrictions.

This broader development is necessary for the long-term sustainability of the community. While quality housing has provided the foundation from which to grow, the community also needs a means of independently making a living, which this range of initiatives has been co-designed to provide.

6. Core Principles

The purpose of this paper is not to describe an empirical model which should (or could) be rigidly replicated. Rather, the authors’ intention is to present an example case study which produced successful results and to analyse the challenges and learnings throughout the process to assist in the advancement of new solutions for remote Indigenous housing. By following a broad set of principles, rather than prescribed methods or designs, projects will be more likely to achieve the necessary flexibility and adaptability to local needs and conditions. By comparison, the typical approach thus far—of externalizing, compartmentalising, and homogenising—has generally not produced successful outcomes much beyond the ribbon-cutting ceremony. The challenges faced by remote communities are too multi-faceted and interconnected to be solved by treating each problem in isolation. The FISH–Bawoorrooga project applied the following core principles:

- Co-design: By genuinely enabling communities to design their dwellings, the results will be far more culturally appropriate and tailored to the needs of the people who will reside in them. As well as creating more functional houses, this factor is essential for residents’ sense of ownership. Incorporating community members at all stages is key in addressing the complexity of the challenges faced in these communities.

- Design suited to local climate: Passive solar design principles were used in this project. The Bawoorrooga house achieves its aim of passively mitigating climate extremes and providing consistent thermal comfort at low ongoing expense. Design solutions should always adapt to the place and local climate.

- Co-build: By heavily involving community members in the physical construction, the participants develop relevant skills and form a strong psychological investment in the house. As with co-design, this fosters pride and ownership and enables the community to take care of and maintain their house. It can also mitigate the project labour costs.

- Sustainable, local resources: Locally abundant resources, such as earth, are often more sustainable, cheaper, highly functional, and culturally preferred.

- Concurrent community initiatives: It is often possible to incorporate other essential community initiatives within the project framework, such as education, youth support and prison diversion programs, community governance, and enterprise development. Ideally, this would be done through longer-term partnerships, e.g., working with communities beyond the completion of a specific project. This allows progress to be consolidated and built upon, rather than the common scenario where support disappears suddenly, and isolated gains are quickly reversed.

7. Conclusions and Recommendations

It has long been evident that the model of remote Indigenous housing must change as it has failed for decades to achieve the most basic measure of success—namely minimally habitable accommodation—let alone broader measures of social and emotional wellbeing. As tempting as it may be for governments to try a “one-size-fits-all” approach to remote housing, this path is ultimately expensive and ineffective, ignoring the necessary relationship between people and place. As noted by Rusch and Best in their 2014 review of remote housing, “achieving change requires much more than the design of structure; it is about recognizing the potential in people to control and manage their own affairs and removing the obstacles and constraints of legislation which prevent them realising that potential” [7].

Co-design and co-build projects are slower and more complex than the conventional model of external contracting because they require community engagement, and they take a more comprehensive approach to local needs and conditions. However, outcomes can be far superior across a broad range of areas, including social and emotional wellbeing, house quality and comfort, energy consumption, long-term maintenance, community physical and mental health, and pride and ownership. These factors are essential in breaking intergenerational cycles of poverty, trauma, and engagement with the justice system. If chronic and systemic issues remain unaddressed, then governments—through one department or another—are obliged to pick up the cost.

This paper outlines the key challenges we faced throughout the project. Some of these challenges would likely be common across a broad range of remote contexts and communities and, therefore, would need to be factored into any project of this type. However, many of the obstacles we faced were unique to our circumstances and need not apply to future projects, particularly the desperate funding shortages we faced throughout the entire duration. Notwithstanding these hurdles, the project achieved outcomes far exceeding the mere provision of a house. In addition to providing a high-quality and moderate-cost house, the project notably enhanced community social and emotional wellbeing. A similar project, if properly financed from the outset, would be expected to achieve even better results in a shorter timeframe.

Given our state and federal governments’ stated desire to address the chronic difficulties faced by Australia’s Indigenous communities, including the costly dependence on government services and welfare, it would be worthwhile paying close attention to Bawoorrooga-style initiatives. The Bawoorrooga leaders are clear about what they want: “We want to be self-sufficient on our homeland—show the government we can do it. To be independent. You get healed from homeland—it’s a safe place”.

Change is well overdue. Sustainable, local, community-oriented solutions exist and have been consistently proven successful. It is now time to adopt them. When Bawoorrooga Community members finished building their home, they proudly said to us, “the Government is going to look at this thing—what we’ve created, what we’ve done—and it’s going to go forward”.

Author Contributions

Conceptualisation and methodology, K.R., J.R., V.H. and S.V.M.; project delivery, K.R. and J.R.; analysis, K.R., J.R., V.H. and S.V.M.; diagrams and graphics, J.R.; writing—original draft preparation, K.R.; writing—review and editing, J.R., V.H. and S.V.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding, as it was incidental to FISH’s community development project at Bawoorrooga. However, we acknowledge the following entities for their contributions to the project: WA Department of Communities, Marra Worra Worra Aboriginal Corporation, Bendat Family Foundation, Argyle Diamond Mine, Newcrest Mining, and other generous private donors.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge Claude Carter and Andrea Pindan, who have been partners to this project since its inception. Claude and Andrea brought their cultural understanding, values, and leadership to the project all throughout the co-design and co-build stages. Their dedication to retaining their traditional culture in the modern world is invaluable to their community, to our society, and to all the future generations who will inherit this cultural wisdom. The authors also acknowledge the tireless work of Mark Anderson. Without Mark’s dedication, insight, and leadership the project would not have been possible.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Phibbs, P.; Thompson, S. The Health Impacts of Housing: Toward a Policy-Relevant Research Agenda; AHURI Final Report No. 173; Australian Housing and Urban Research Institute Limited: Victoria, Australia, 2011; p. 5. Available online: https://www.ahuri.edu.au/research/final-reports/173 (accessed on 14 January 2022).

- Quinterno, J.; Mary Reynolds Babcock Foundation. Helping People and Places Move Out of Poverty—Progress and Learning 2010; Briefing Paper. pp. 17, 22. Available online: https://www.mrbf.org/sites/default/files/midcoursereview.pdf (accessed on 13 January 2022).

- Kothari, M. United Nations Special Rapporteur on Adequate Housing; Mission to Australia; Preliminary Observations: Canberra, Australia, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- NITV. SBS Australia. Available online: https://www.sbs.com.au/nitv/the-point-with-stan-grant/article/2017/04/03/un-rapporteur-slams-governments-record-indigenous-issues-hopeful-change (accessed on 5 January 2022).

- Lea, T.; Grealy, L.; Moskos, M.; Brambilla, A.; King, S.; Habibis, D.; Benedict, R.; Phibbs, P.; Sun, C.; Torzillo, P. Sustainable Indigenous Housing in Regional and Remote Australia; AHURI Final Report No. 368; Australian Housing and Urban Research Institute Limited: Victoria, Australia, 2021; pp. 2–3. Available online: https://www.ahuri.edu.au/research/final-reports/368 (accessed on 5 January 2022).

- Ciancio, D.; Beckett, C. Rammed Earth: An Overview of a Sustainable Construction Material. In Proceedings of the Third International Conference on Sustainable Construction Materials and Technologies, Kyoto, Japan, 18–22 August 2013; pp. 1–2. [Google Scholar]

- Rusch, R.; Best, R. Sustainability: Its adaptation and relevance in remote area housing. Australas. J. Constr. Econ. Build. 2014, 14, 88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- United Nations Association of Australia WA Division. Available online: https://www.unaa-wa.org.au/post/united-nations-day-2019-gala (accessed on 13 January 2022).

- Banksia Foundation. Available online: https://banksiafdn.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/Ebook-2019_double-pages.pdf (accessed on 13 January 2022).

- Romero, J. SuperAdobe Self-Build Sustainable House. The Architect WA Homes Edition. 2020, pp. 86–88. Available online: https://www.architecture.com.au/wp-content/uploads/The-Arch_WA-Homes_AW2020_ONLINE-VERSION.pdf (accessed on 13 January 2022).

- Communities Containing Examples of These Natural Building Approaches Include: Aldeafeliz, San Francisco, Colombia; Proyecto Gaia, Santa Sofia Boyacá Colombia; Tierra Langla, Lunahuana, Peru; Baza Ulmu, Tautii Margheraus, Romania.

- Beckett, C.; Ciancio, D.; Hubner, C.; Cardell-Oliver, R. Sustainable and Affordable Rammed Earth Houses in Kalgoorlie, Western Australia: Development of Thermal Monitoring Techniques. In Proceedings of the Australasian Structural Engineering Conference, Aukland, NZ, USA, 9–11 July 2014; p. 1. [Google Scholar]

- Mudrooroo. Us Mob: History, Culture, Struggle: An Introduction to Indigenous Australia; Angus & Robertson: Sydney, Australia; New York, NY, USA, 1995; p. 34. [Google Scholar]

- Hunter, K.; Kiffmeyer, D. Earthbag Building: The Tools, Tricks, and Techniques; New Society Publishers: Gabriola Island, BC, Canada, 2004; Available online: https://archive.org/details/eb_Earthbag_Building-The_Tools_Tricks_and_Techniques (accessed on 24 February 2022).