Transit-Oriented Development: Towards Achieving Sustainable Transport and Urban Development in Jakarta Metropolitan, Indonesia

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

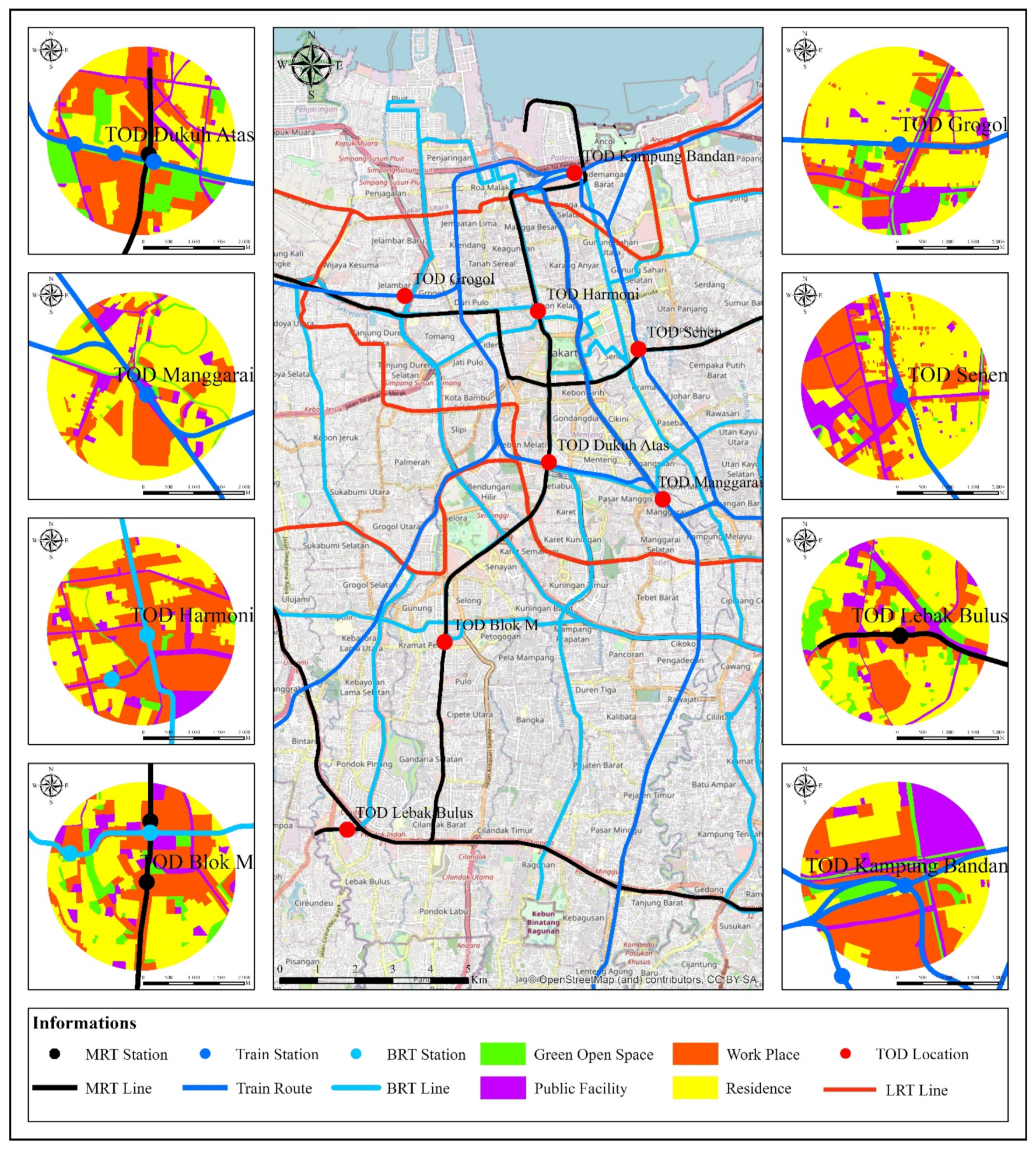

2.1. The Jakarta Metropolitan Area

2.2. Geographic Information System (GIS) and Analysis of Land-Use Changes

- LUDI (land use diversity index): this is an index used for representing the land-use mix or homogeneity rate of land use in a given area.

- li: the ratio of a particular area of the land-use category to the total area being analyzed.

- li multiplied with the (ln i) which is divided by the total area (ln 4) within the TOD area with four land-use categories.

2.3. Survey of 400 Daily Commuters Who Live in Planned TOD Areas in 2013 and Repeated in 2020

3. Results

3.1. The Changes of Land-Use and Spatial Distribution within TOD Areas between 2013 and 2020

3.2. Housework: Changes in Commuters’ Preference between 2013 and 2020

3.3. Changes in Commuters’ Travel Behavior between 2013 and 2020

3.4. Changes in Commuters’ Travel Behavior Impacted COVID-19

4. Discussion

4.1. The Changes of Land-Use and Spatial Distribution

4.2. The Change of Commuters’ Preference to Choose Workplace and Housing Locations

4.3. The Change of Commuters’ Travel Behavior

5. Conclusions

- Through a geospatial information system analysis and survey of 400 daily commuters who live within a 1 km radius of the planned TOD case study areas conducted in 2013 and 2020, our study examined changes in the spatial distribution of land use and commuters’ travel behavior, determining the extent to which TOD implementation influenced these changes, thereby informing appropriate future policies. While acknowledging the importance of land-use diversity and accessibility within the modes of transit transportation, i.e., the physical aspect of which has become a major focus of the existing TOD literature, our research findings revealed a significant weight on social and culture as key factors that influenced commuters’ travel behavior, with kinship relations being the main reason for choosing housing locations.

- A significant increase in public facilities at the expense of green open space (GOS) indicates that TOD implementation was conducted by the government with the sole authority to manage GOS, lacking private sector involvement.

- Our study found workplace and home culture as key factors for commuters’ decisions to support TOD implementation, highlighting socio-cultural elements as key determining factors toward achieving sustainable urban transportation and development. The cost factor was the commuters’ main reason for using public or private modes of transportation, reflecting specific mobility habits and local culture. Therefore, we call for policymakers and urban planners to consider these aspects when designing transit areas and enhancing accessibility to commuters’ housing locations and workplaces. Specifically, the workplace is important because commuters cannot change employment easily.

- We also found that the COVID-19 pandemic has not caused significant change in the mobility behavior pattern of commuters who live within planned TOD areas in the Jakarta Metropolitan areas. This is attributed to the factor that commuters’ ability to change employment is limited. Following our research findings, our policy recommendations comprise two aspects on which governments should focus: (1) improving public transportation modes which are affordable, and (2) establishing good access and connectivity between housing and workplaces.

- There are several key limitations of this study, and we recommend that future research pays particular attention toward addressing them. Firstly, our sampled population consisted of commuters who live within a 1 km radius of the planned TOD areas. Thus, they may not have all the attributes that comprehensively match with the characteristics of the overall commuting population. Secondly, we surveyed different individuals as research respondents between 2013 and 2020. Therefore, the survey results might not prove the relationships and consistencies of the same commuters. Moreover, future research is required to include workers whose workplaces are within those planned TOD areas to explore their dominant travel behaviors and the relationship between the points of origin and destination within TOD areas.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Abdi, M.H.; Lamíquiz-Daudén, P.J. Transit-oriented development in developing countries: A qualitative meta-synthesis of its policy, planning and implementation challenges. Int. J. Sustain. Transp. 2020, 16, 195–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, R.; Bertolini, L. Defining critical success factors in TOD implementation using rough set analysis. J. Transp. Land Use 2017, 10, 139–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cervero, R. The Transit Metropolis: A Global Inquiry; Island Press: Washington, DC, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Loukaitou-Sideris, A. Transit-Oriented Development in the Inner City: A Delphi Survey. J. Public Transp. 2001, 3, 75–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ewing, R.; Cervero, R. Travel and the Built Environment. J. Am. Plan. Assoc. 2010, 76, 265–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curtis, C.; Scheurer, J. Planning for sustainable accessibility: Developing tools to aid discussion and decision-making. Prog. Plan. 2010, 74, 53–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Handy, S.L. Accessibility- vs. Mobility-Enhancing Strategies for Addressing Automobile Dependence in the U.S.; University of California at Davis Recent Work: Davis, CA, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Papa, E.; Bertolini, L. Accessibility and Transit-Oriented Development in European metropolitan areas. J. Transp. Geogr. 2015, 47, 70–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, P.; He, D.; Chen, Y.; Christopher Zegras, P.; Jiang, Y. Transit-oriented development and air quality in Chinese cities: A city-level examination. Transp. Res. Part D Transp. Environ. 2019, 68, 10–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibraeva, A.; de Correia, G.H.A.; Silva, C.; Antunes, A.P. Transit-oriented development: A review of research achievements and challenges. Transp. Res. Part A Policy Pract. 2020, 132, 110–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyu, G.; Bertolini, L.; Pfeffer, K. How does transit-oriented development contribute to station area accessibility? A study in Beijing. Int. J. Sustain. Transp. 2020, 14, 533–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Samsura, D.A.A.; van der Krabben, E. Institutional barriers to financing transit-oriented development in China: Analyzing informal land value capture strategies. Transp. Policy 2019, 82, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suzuki, H.; Murakami, J.; Hong, Y.-H.; Tamayose, B. Financing Transit-Oriented Development with Land Values: Adapting Land Value Capture in Developing Countries; World Bank Publications: Washington, DC, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Vongpraseuth, T.; Seong, E.Y.; Shin, S.; Kim, S.H.; Choi, C.G. Hope and reality of new towns under greenbelt regulation: The case of self-containment or transit-oriented metropolises of the first-generation new towns in the Seoul Metropolitan Area, South Korea. Cities 2020, 102, 102699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dargay, J.; Hanly, M. The impact of land use patterns on travel behaviour. In Proceedings of the European Transport Conference (Etc), Strasbourg, France, 8–10 October 2003; p. 15. [Google Scholar]

- Loo, B.P.Y.; Chow, A.S.Y. Changing Urban Form in Hong Kong: What Are the Challenges on Sustainable Transportation? Int. J. Sustain. Transp. 2008, 2, 177–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, M.; Hickman, R. Understanding travel and differential capabilities and functionings in Beijing. Transp. Policy 2019, 83, 46–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gim, T.-H.T. Analyzing the city-level effects of land use on travel time and CO2 emissions: A global mediation study of travel time. Int. J. Sustain. Transp. 2021, 15, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zegras, P.C.; Srinivasan, S. Household Income, Travel Behavior, Location, and Accessibility. Transp. Res. Rec. J. Transp. Res. Board 2007, 2038, 128–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schirmer, P.M.; Van Eggermond, M.A.B.; Axhausen, K.W. The role of location in residential location choice models: A review of literature. J. Transp. Land Use 2014, 7, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasibuan, H.S.; Soemardi, T.P.; Koestoer, R.; Moersidik, S. The Role of Transit Oriented Development in Constructing Urban Environment Sustainability, the Case of Jabodetabek, Indonesia. Procedia Environ. Sci. 2014, 20, 622–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, C.; Kim, S.W.; Kang, H.J.; Song, S.M. What makes urban transportation efficient? Evidence from subway transfer stations in Korea. Sustainability 2017, 9, 2054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berawi, M.A.; Saroji, G.; Iskandar, F.A.; Ibrahim, B.E.; Miraj, P.; Sari, M. Optimizing Land Use Allocation of Transit-Oriented Development (TOD) to Generate Maximum Ridership. Sustainability 2020, 12, 3798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cervero, R.; Murakami, J. Rail and Property Development in Hong Kong: Experiences and Extensions. Urban Stud. 2009, 46, 2019–2043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Guo, H.L.; Li, H.; Xu, G.H.; Wang, Z.R.; Kong, C.W. Transit-Oriented Land Planning Model Considering Sustainability of Mass Rail Transit. J. Urban Plan. Dev. 2010, 136, 243–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, X.; Chen, X.; Li, X.; Ding, C.; Wang, Y. Sustainable station-level planning: An integrated transport and land use design model for transit-oriented development. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 170, 1052–1063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, J.J.; Li, C.N. A grey programming model for regional transit-oriented development planning. Pap. Reg. Sci. 2008, 87, 119–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Central Bureau of Statistics. Jabodetabek Commuter Statistics. 2019. Available online: https://www.bps.go.id/publication/2019/12/04/eab87d14d99459f4016bb057/statistik-komuter-jabodetabek-2019.html (accessed on 5 August 2020).

- Xie, K.; Liang, B.; Dulebenets, M.A.; Mei, Y. The Impact of Risk Perception on Social Distancing during the COVID-19 Pandemic in China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 6256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsoy, D.; Tirasawasdichai, T.; Kurpayanidi, K.I. Role of Social Media in Shaping Public Risk Perception during COVID-19 Pandemic: A Theoretical Review. Int. J. Manag. Sci. Bus. Adm. 2021, 7, 35–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malecki, K.; Keating, J.A.; Safdar, N. Crisis communication and public perception of COVID-19 risk in the era of social media. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2021, 72, 697–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khorram-Manesh, A.; Dulebenets, M.A.; Goniewicz, K. Implementing Public Health Strategies—The Need for Educational Initiatives: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 5888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siegrist, M.; Luchsinger, L.; Bearth, A. The Impact of trust and risk perception on the acceptance of measures to reduce COVID-19 cases. Risk Anal. 2021, 41, 787–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, J.; Zou, H.; Xie, K.; Dulebenets, M.A. An Assessment of Social Distancing Obedience Behavior during the COVID-19 Post-Epidemic Period in China: A Cross-Sectional Survey. Sustainability 2021, 13, 8091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demographia. Demographia World Urban Areas. In Demographia World Urban Areas, 16th ed.; Demographia: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- JICA. The Study on Integrated Transportation Master Plan for Jabodetabek: Final Report Summary Report; JICA: Tokyo, Japan, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- JICA. Project for the Study on JABODETABEK Public Transportation Policy Implementation Strategy (JAPTraPis)—Final Report: Main Text; JICA: Tokyo, Japan, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- BPS. Statistics of DKI Jakarta Province. In Jakarta in Figures 2015; Jakarta Bureau Statistics: Jakarta, Indonesia, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Transportation. National Transportation Data (in Bahasa); Central of Bureau Statistics: Jakarta, Indonesia, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Jakarta Provincial Government. Regulation of Jakarta No. 1 Year 2014 about Detailed Spatial Plan and Zoning Regulation; Jakarta Provincial Government: Jakarta, Indonesia, 2014.

- Jakarta Provincial Government. Regulation of Jakarta No. 140 Year 2017 about Assignment of PT. MRT Jakarta as the Main Operator of The TOD Corridor (North-South) of Phase 1 MRT Jakarta; Jakarta Provincial Government: Jakarta, Indonesia, 2017.

- Government Republic of Indonesia. President Regulation No. 55 Year 2018 about Transportation Master Plan of Jakarta, Bogor, Depok, Tangerang, and Bekasi; Government Republic of Indonesia: Jakarta, Indonesia, 2018.

- Cervero, R.; Kockelman, K. Travel demand and the 3Ds: Density, diversity, and design. Transp. Res. Part D Transp. Environ. 1997, 2, 199–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ann, S.; Jiang, M.; Yamamoto, T. Re-examination of the standards for transit oriented development influence zones in India. J. Transp. Land Use 2019, 12, 679–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Congalton, R.G. Accuracy assessment and validation of remotely sensed and other spatial information. Int. J. Wildland Fire 2001, 10, 321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calthorpe, P. The Next American Metropolis: Ecology, Community, and the American Dream; Princeton Architectural Press: New York, NY, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Curtis, C.; Renne, J.L.; Bertolini, L. Transit oriented development: Making it Happen. In Transit Oriented Development: Making it Happen; Ashgate Publishing, Ltd.: Farnham, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Knowles, R.D.; Ferbrache, F.; Nikitas, A. Transport’s historical, contemporary and future role in shaping urban development: Re-evaluating transit oriented development. Cities 2020, 99, 102607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansury, Y.S.; Tontisirin, N.; Anantsuksomsri, S. The impact of the built environment on the location choices of the creative class: Evidence from Thailand. Reg. Sci. Policy Pract. 2012, 4, 183–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakamura, K.; Gu, F.; Wasuntarasook, V. Failure of Transit-Oriented Development in Bangkok from a Quality of Life Perspective. Asian Transp. Stud. 2016, 4, 194–209. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, J.-J.; Jen, Y.-C. Household Attributes in a Transit-Oriented Development: Evidence from Taipei. J. Public Transp. 2009, 12, 105–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, N. Impacts of Transit-Oriented Development (TOD) eon the Travel Behavior of its Residents in Shenzhen, China. Master’s Thesis, University of Waterloo, Waterloo, ON, Canada, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Dirgahayani, P.; Syabri, I.; Waluyo, N.P. Land Governance for Transit Oriented Development in Densely Built Urban Area (Case Study: Jakarta, Indonesia). IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2015, 158, 12019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huston, S.; Darchen, S.; Ladouceur, E. TOD Development in Theory and Practice: The Case of Albion Mill. In Proceedings of the 18th Annual PRRES Conference, Adelaide, Australia, 15–18 January 2012; Volume 2, p. 864. [Google Scholar]

- Pan, H.; Li, J.; Shen, Q.; Shi, C. What determines rail transit passenger volume? Implications for transit oriented development planning. Transp. Res. Part D Transp. Environ. 2017, 57, 52–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Gent, W.; Das, M.; Musterd, S. Sociocultural, economic and ethnic homogeneity in residential mobility and spatial sorting among couples. Environ. Plan. A Econ. Space 2019, 51, 891–912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez, D.A.; Kang, C.-D. A typology of the built environment around rail stops in the global transit-oriented city of Seoul, Korea. Cities 2020, 100, 102663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosalin, A.; Kombaitan, B.; Zulkaidi, D.; Dirgahayani, P.; Syabri, I. Towards Sustainable Transportation: Identification of Development Challenges of TOD area in Jakarta Metropolitan Area Urban Railway Projects. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2019, 328, 012006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahlan, A.F.; Fraszczyk, A. Public Perceptions of a New MRT Service: A Prelaunch Study in Jakarta. Urban Rail Transit. 2019, 5, 278–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, W.; Wang, M.; Zhang, F. Commuting behavior and congestion satisfactionevidence from Beijing, China. Transp. Res. Part D 2019, 67, 553–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Althoff, T.; Sosič, R.; Hicks, J.L.; King, A.C.; Delp, S.L.; Leskovec, J. Large-scale physical activity data reveal worldwide activity inequality. Nature 2017, 547, 336–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Irawan, M.Z.; Rizki, M.; Joewono, T.B.; Belgiawan, P.F. Exploring the intention of out-of-home activities participation during new normal conditions in Indonesian cities. Transp. Res. Interdiscip. Perspect. 2020, 8, 100237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| TOD Areas | Residential (%) | Work Places (%) | Public Facilities (%) | Green Open Spaces (%) | Diversity Index | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2013 | 2020 | 2013 | 2020 | 2013 | 2020 | 2013 | 2020 | 2013 | 2020 | |

| Dukuh Atas | 36.79 | 35.48 | 36.17 | 36.91 | 5.09 | 11.54 | 21.95 | 16.06 | 0.88 | 0.92 |

| Manggarai | 60.15 | 65.64 | 27.85 | 18.91 | 5.78 | 11.61 | 6.22 | 3.83 | 0.72 | 0.70 |

| Harmoni | 18.66 | 33.91 | 66.05 | 48.84 | 5.49 | 15.59 | 9.79 | 1.65 | 0.70 | 0.77 |

| Blok M | 43.97 | 46.39 | 31.40 | 33.18 | 14.80 | 13.49 | 9.74 | 6.94 | 0.89 | 0.85 |

| Grogol | 55.04 | 60.44 | 21.18 | 15.66 | 11.41 | 16.36 | 12.38 | 7.53 | 0.84 | 0.78 |

| Senen | 51.36 | 50.46 | 28.28 | 29.46 | 17.55 | 18.40 | 2.81 | 1.68 | 0.80 | 0.78 |

| Lebak Bulus | 53.09 | 53.50 | 18.80 | 23.49 | 15.66 | 13.05 | 12.45 | 9.95 | 0.87 | 0.84 |

| Kampung Bandan | 25.44 | 25.43 | 45.33 | 42.41 | 12.08 | 23.44 | 17.14 | 8.72 | 0.91 | 0.91 |

| TOD Areas | Residential (%) | Work Places (%) | Public Facilities (%) | Green Open Spaces (%) | Diversity Index | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2013 | 2020 | 2013 | 2020 | 2013 | 2020 | 2013 | 2020 | 2013 | 2020 | |

| Bogor | 50.76 | 48.80 | 31.14 | 17.83 | 3.45 | 20.17 | 14.64 | 13.20 | 0.80 | 0.90 |

| Depok | 78.09 | 67.09 | 8.10 | 11.88 | 3.24 | 7.39 | 10.57 | 13.65 | 0.54 | 0.71 |

| Depok Baru | 65.15 | 65.76 | 15.01 | 15.26 | 2.46 | 7.94 | 17.15 | 11.04 | 0.69 | 0.73 |

| Tangerang | 61.66 | 57.97 | 18.26 | 14.44 | 8.60 | 15.84 | 11.48 | 11.75 | 0.77 | 0.82 |

| Tang-Sel | 75.35 | 66.26 | 2.68 | 4.37 | 2.47 | 5.36 | 19.51 | 24.01 | 0.52 | 0.66 |

| Bekasi | 57.83 | 39.14 | 13.97 | 23.70 | 8.78 | 15.07 | 19.43 | 22.09 | 0.81 | 0.96 |

| 2013 | 2020 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Influencing Factors | East Suburbs | West Suburbs | South Suburbs | East Suburbs | West Suburbs | South Suburbs |

| GOS | 7.50 | 7.60 | 19.30 | 16.60 | 17.40 | 20.20 |

| Social (kinship) | 19.60 | 19.60 | 20.10 | 24.80 | 17.20 | 24.90 |

| Accessibility | 24.60 | 24.60 | 18.30 | 25.30 | 24.20 | 24.70 |

| Price | 21.00 | 21.00 | 19.70 | 21.40 | 24.30 | 21.80 |

| Public Facility | 15.80 | 15.80 | 11.00 | 13.60 | 20.70 | 12.30 |

| Water Facility | 11.50 | 11.50 | 11.70 | 11.20 | 13.60 | 10.20 |

| Near The MRT | 3.70 | 0.00 | 6.10 | |||

| Commuters’ Origin (Bodetabek Areas and Jakarta Suburbs) | Reasons to Choose Workplace Locations 2020 in Percentage (%) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Near CL | Easy Access to Trans-Jakarta Bus | Near MRT/LRT | Place of Employers | Others | |

| 19.3 | 1.8 | 0.9 | 78.9 | 1.8 |

| 20.9 | 7.5 | 0.0 | 71.6 | 0.0 |

| 21.7 | 0.0 | 1.6 | 54.3 | 22.5 |

| Public Transportation Usage | |||||||||

| Commuters’ Origin | 2013 | 2020 | |||||||

| KRL Commuter Lines | Bus | BRT Trans-Jakarta | City Mini Bus | KRL Commuter Lines | Bus | BRT Trans-Jakarta | City Mini Bus | MRT | |

| East suburbs of Jakarta | 57.1 | 5.2 | 0.6 | 13.0 | 57.9 | 3.5 | 10.5 | 0.0 | 0.9 |

| West suburbs of Jakarta | 8.3 | 21.4 | 6.5 | 11.7 | 72.4 | 0.0 | 7.5 | 1.5 | 1.5 |

| South suburbs of Jakarta | 54 | 10.0 | 0.0 | 5.0 | 58.9 | 0.0 | 4.7 | 0.8 | 14.0 |

| Private Transportation Usage | |||||||||

| 2013 | 2020 | ||||||||

| Car | Motorbike | Bicycle | Car | Motorbike | Bicycle | ||||

| East suburbs of Jakarta | 5.2 | 29.9 | 1.3 | 19.3 | 43.0 | 0.0 | |||

| West suburbs of Jakarta | 10.2 | 28.9 | 0.0 | 5.2 | 69.4 | 1.5 | |||

| South suburbs of Jakarta | 17.5 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 16.3 | 50.4 | 0.8 | |||

| Suburbs | Reasons to Use Public Transport (In Percentage (%)) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| New Transport Infrastructure (MRT, LRT) | Better Connectivity of Trans-Jakarta Bus | Pedestrian Space | Cost | |

| East suburbs of Jakarta | 9.6 | 11.4 | 0.0 | 31.6 |

| West suburbs of Jakarta | 23.9 | 22.4 | 1.5 | 29.1 |

| South suburbs of Jakarta | 38.0 | 16.3 | 8.5 | 31.0 |

| Item/Sub-Urbs | No | Yes | No Answer |

|---|---|---|---|

| Use of train from the station | |||

| East suburbs of Jakarta | 48.4 | 51.6 | 0 |

| West suburbs of Jakarta | 72.0 | 28.0 | 0 |

| South suburbs of Jakarta | 37.0 | 63.0 | 0 |

| Changes in traveling time and frequency | |||

| East suburbs of Jakarta | 46.5 | 53.5 | 0 |

| West suburbs of Jakarta | 25.0 | 63.0 | 12 |

| South suburbs of Jakarta | 71.0 | 27.0 | 2.0 |

| Changes in mobility due to service limitations | |||

| East suburbs of Jakarta | 26.8 | 66.8 | 6.4 |

| West suburbs of Jakarta | 34.0 | 43.0 | 22.0 |

| South suburbs of Jakarta | 20.0 | 58.0 | 2.0 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hasibuan, H.S.; Mulyani, M. Transit-Oriented Development: Towards Achieving Sustainable Transport and Urban Development in Jakarta Metropolitan, Indonesia. Sustainability 2022, 14, 5244. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14095244

Hasibuan HS, Mulyani M. Transit-Oriented Development: Towards Achieving Sustainable Transport and Urban Development in Jakarta Metropolitan, Indonesia. Sustainability. 2022; 14(9):5244. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14095244

Chicago/Turabian StyleHasibuan, Hayati Sari, and Mari Mulyani. 2022. "Transit-Oriented Development: Towards Achieving Sustainable Transport and Urban Development in Jakarta Metropolitan, Indonesia" Sustainability 14, no. 9: 5244. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14095244

APA StyleHasibuan, H. S., & Mulyani, M. (2022). Transit-Oriented Development: Towards Achieving Sustainable Transport and Urban Development in Jakarta Metropolitan, Indonesia. Sustainability, 14(9), 5244. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14095244