Bottlenose Dolphin Responses to Boat Traffic Affected by Boat Characteristics and Degree of Compliance to Code of Conduct

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Methods

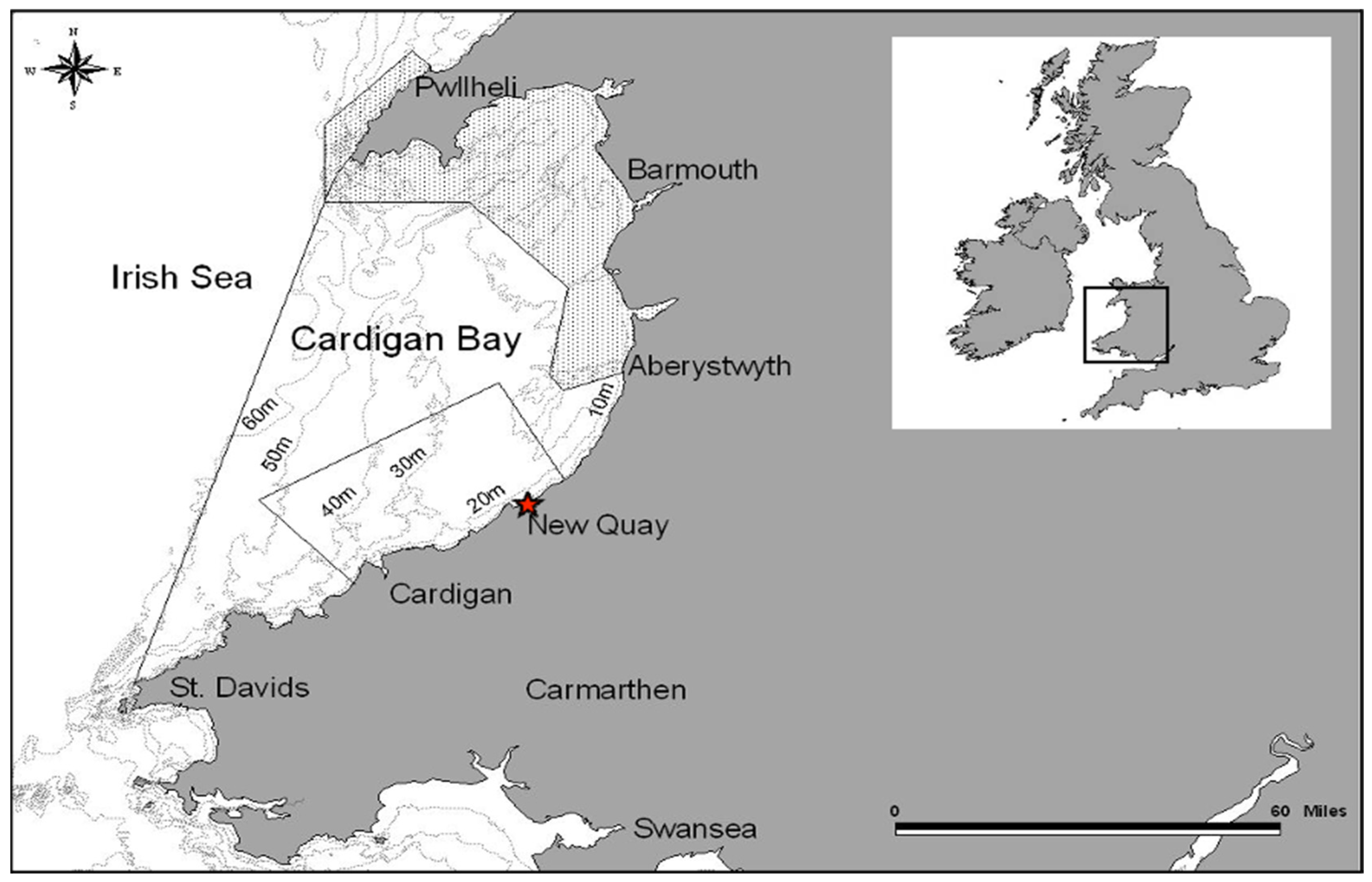

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Data Collection Protocols

2.3. Data Sources and Data Preparation for Analyses

2.4. Analyses

3. Results

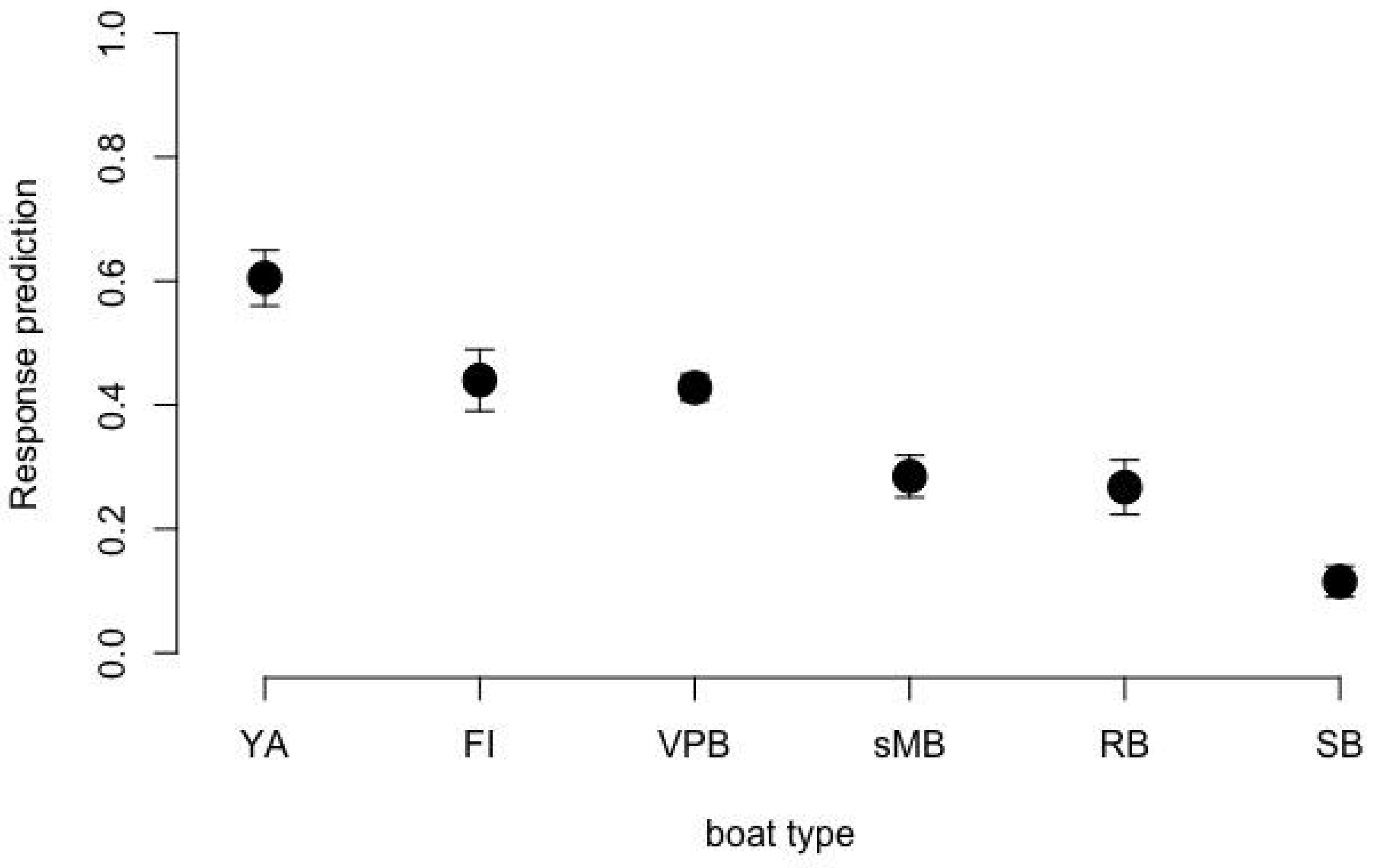

3.1. Dolphin Responses to Different Boat Types

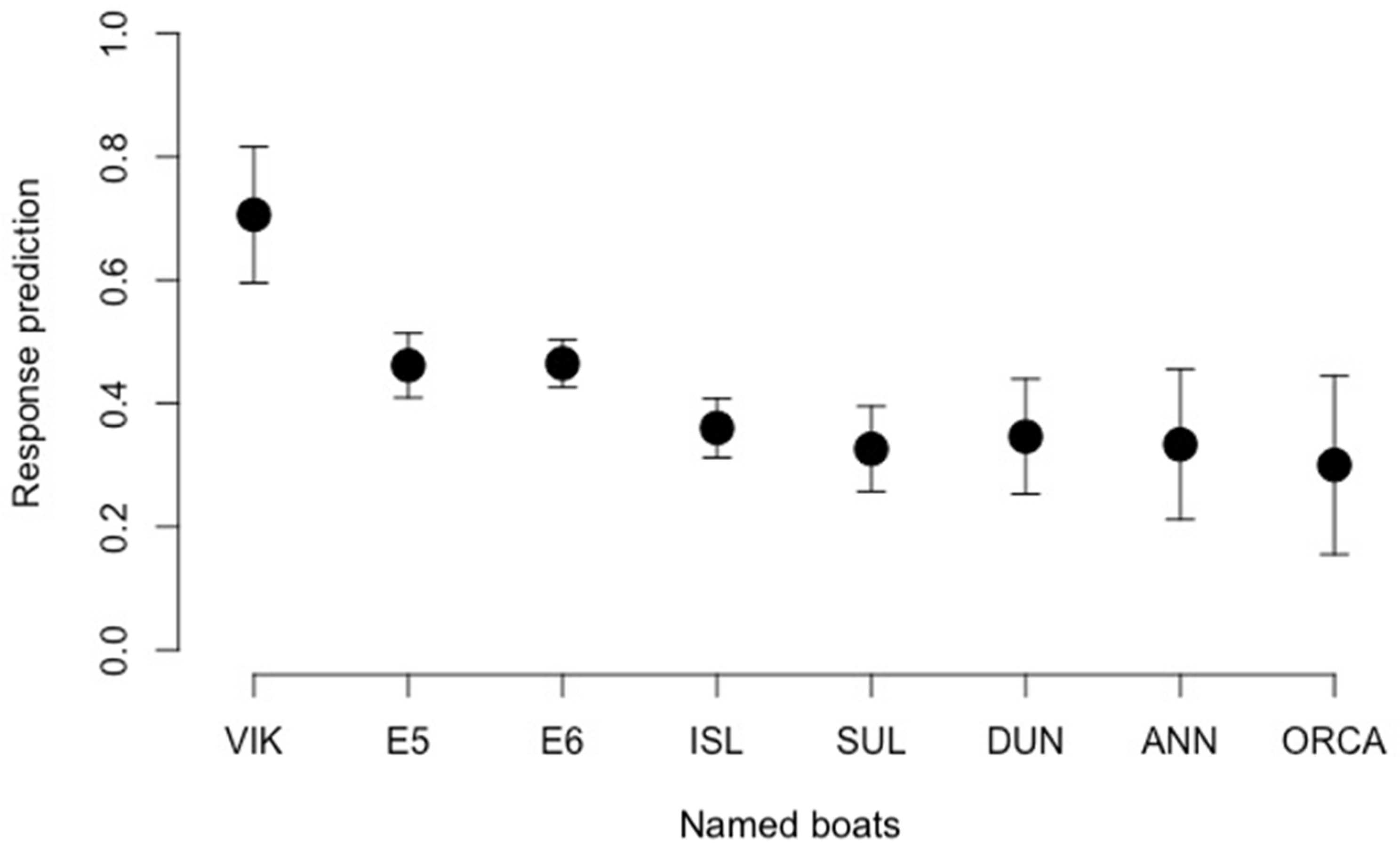

3.2. Dolphin Responses to Operations by Named Boats

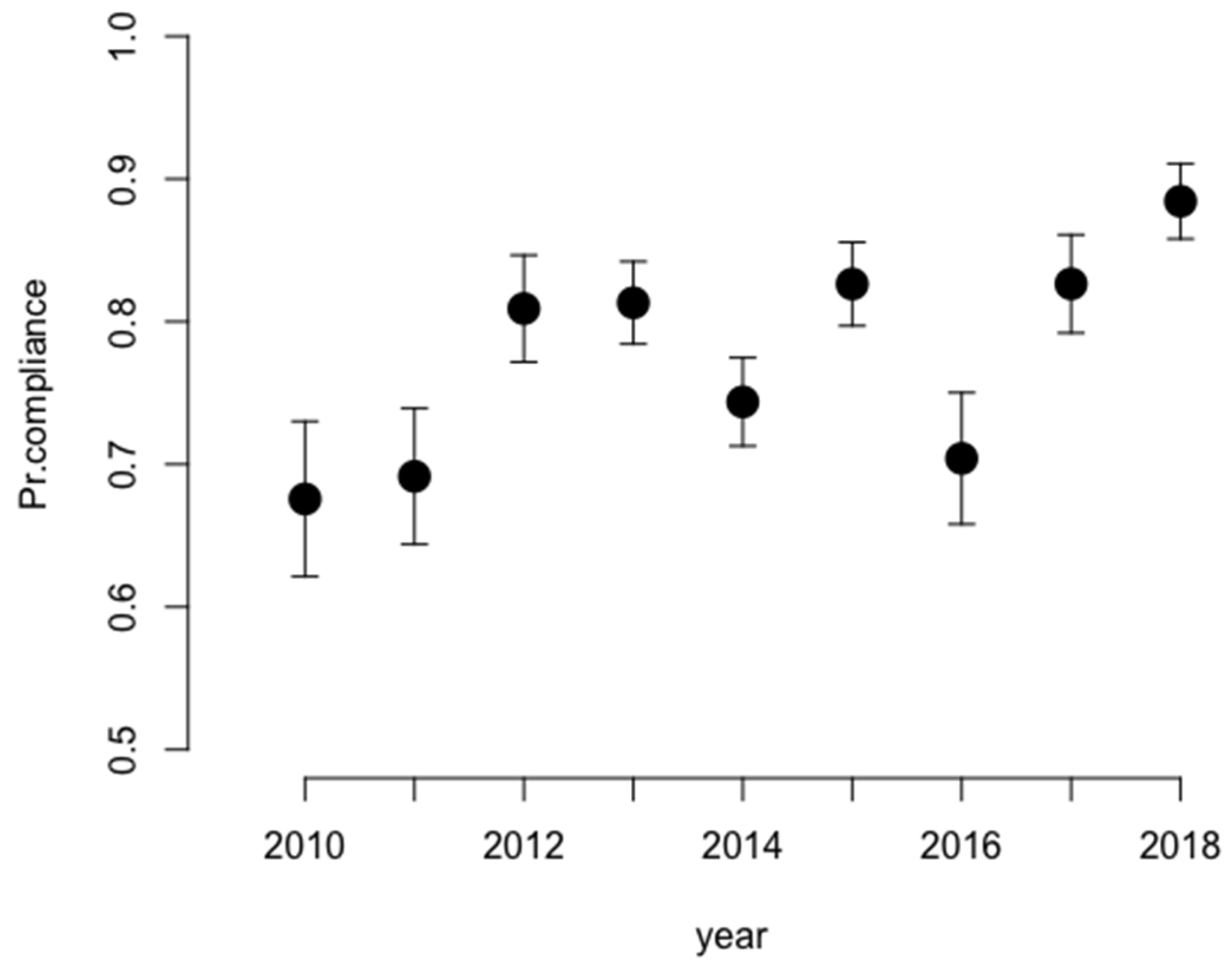

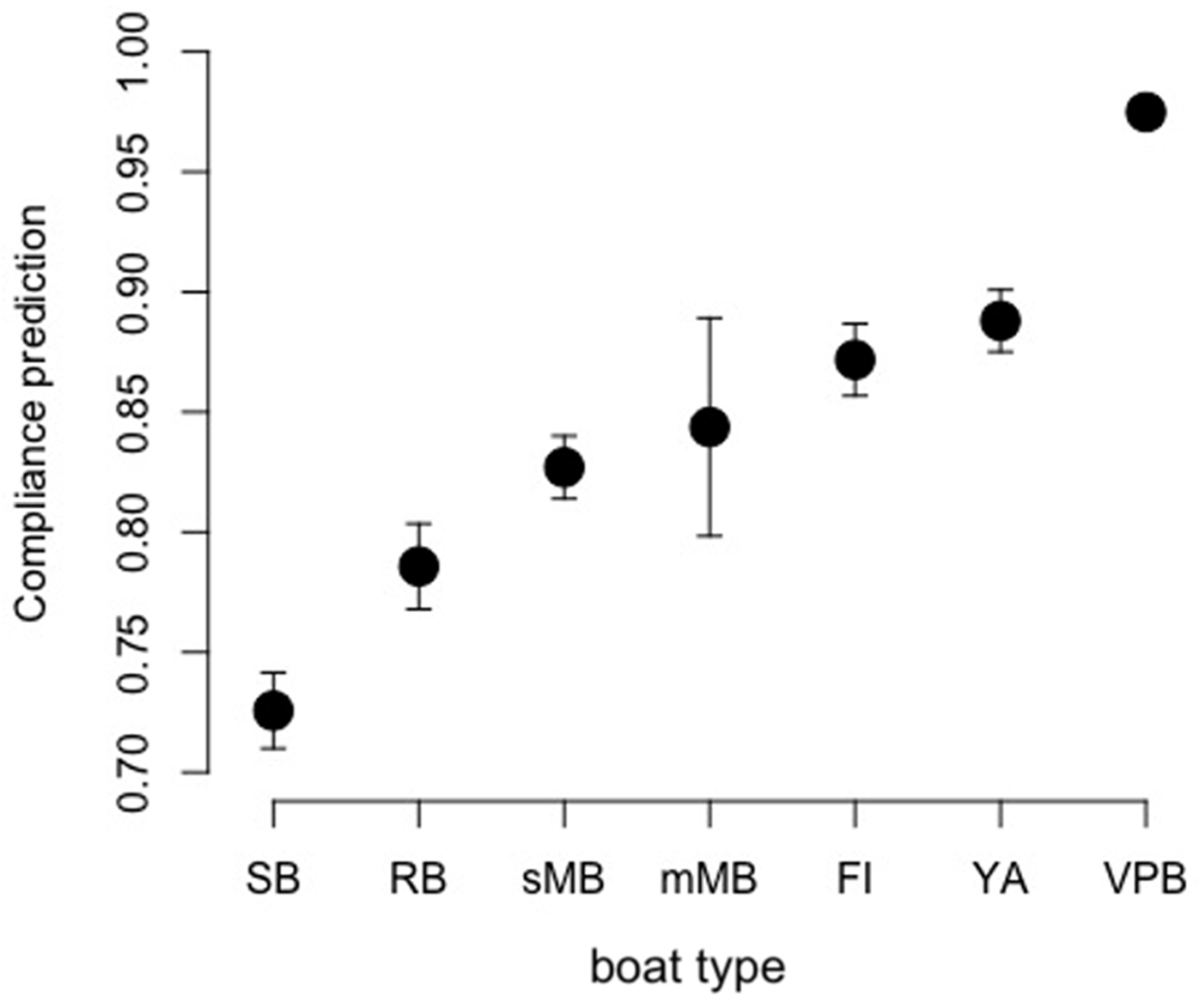

3.3. Compliance with Code of Conduct by Boat Type, 2010–2018

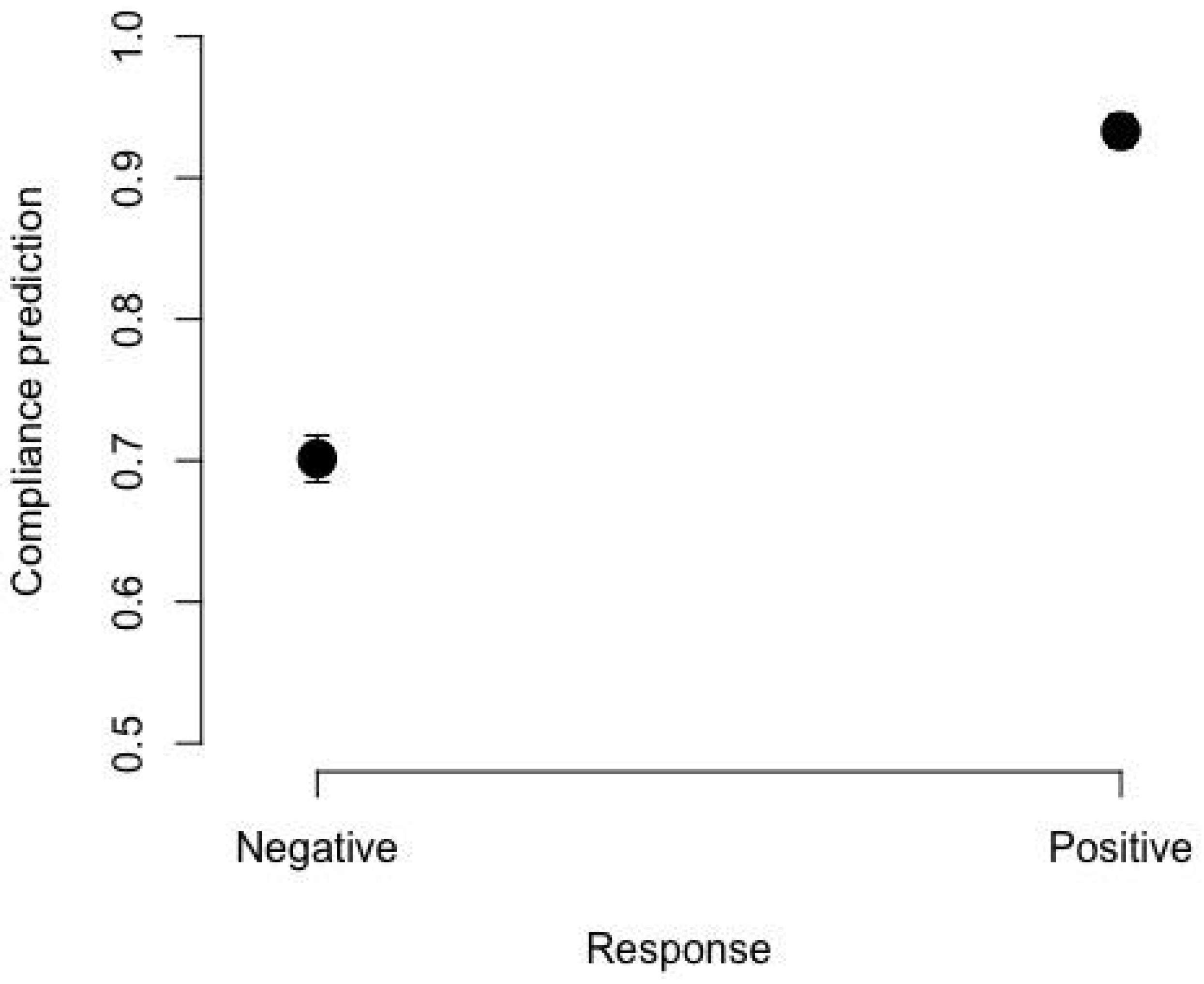

3.4. Dolphin Response to Boat Compliance with the Code of Conduct

4. Discussion

4.1. The Benefit of Research for the Community and the Good of Cardigan Bay, the Bottlenose Dolphins and Ocean Literacy: How It Works Now, and What Can Be Improved

4.2. Conclusions

4.3. Recommendations

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ryabinin, V.; Barbiere, J.; Haugan, P.; Kullenberg, G.; Smith, N.; McLean, C.; Troisi, A.; Fischer, A.; Arico, S.; Aarup, T.; et al. The UN decade of ocean science for sustainable development. Front. Mar. Sci. 2019, 6, 470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Selig, E.R.; Hole, D.G.; Allison, E.H.; Arkema, K.K.; McKinnon, M.C.; Chu, J.; Sherbinin, A.; Fischer, B.; Glew, L.; Holland, M.B.; et al. Mapping global human dependence on marine ecosystems. Conserv. Lett. 2019, 12, e12617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ebarvia, M.C.M. Economic Assessment of Oceans for Sustainable Blue Economy Development. J. Ocean Coast. Econ. 2016, 2, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heymans, J.J.; Bundy, A.; Christensen, V.; Coll, M.; Mutsert, K.; Fulton, E.A.; Piroddi, C.; Shin, Y.J.; Steenbeek, J.; Travers-Trolet, M. The Ocean Decade: A True Ecosystem Modeling Challenge. Front. Mar. Sci. 2020, 7, 766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sordello, R.; Ratel, O.; de Lachapelle, F.F.; Leger, C.; Dambry, D.; Vanpeene, S. Evidence of the impact of noise pollution on biodiversity: A systematic map. Environ. Evid. 2020, 9, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duarte, C.M.; Chapuis, L.; Collin, S.P.; Costa, D.P.; Devassy, R.P.; Eguiluz, V.M.; Erbe, C.; Gordon, T.A.C.; Halpern, B.S.; Havlik, M.N.; et al. The soundscape of the Anthropocene ocean. Science 2021, 371, 581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, B.S.; Gillen, J.; Friess, D.A. Challenging the principles of ecotourism: Insights from entrepreneurs on environmental and economic sustainability in Langkawi, Malaysia. J. Sustain. Tour. 2018, 26, 257–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Traverso, F.; Gaggero, T.; Tani, G.; Rizzuto, E.; Trucco, A.; Viviani, M. Parametric Analysis of Ship Noise Spectra. IEEE J. Ocean. Eng. 2017, 42, 424–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macgillivray, A.; de Jong, C. A reference spectrum model for estimating source levels of marine shipping based on automated identification system data. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2021, 9, 369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoeman, R.P.; Patterson-Abrolat, C.; Plön, S. A Global Review of Boat Collisions with Marine Animals. Front. Mar. Sci. 2020, 7, 292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arcangeli, A.; Crosti, R. The short-term impact of dolphin-watching on the behaviour of bottlenose dolphins (Tursiops truncatus) in western Australia. J. Mar. Anim. Ecol. 2008, 2, 3–9. Available online: https://jmate.ca/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/200921arcangeli.pdf (accessed on 20 April 2022).

- Erbe, C.; Marley, S.A.; Schoeman, R.P.; Smith, J.N.; Trigg, L.E.; Embling, C.B. The Effects of Ship Noise on Marine Mammals—A Review. Front. Mar. Sci. 2019, 6, 606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pellegrini, A.Y.; Romeu, B.; Ingram, S.N.; Daura-Jorge, F.G. Boat disturbance affects the acoustic behaviour of dolphins engaged in a rare foraging cooperation with fishers. Anim. Conserv. 2021, 24, 613–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lusseau, D. Effects of Tour Boats on the Behavior of Bottlenose Dolphins: Using Markov Chains to Model Anthropogenic Impacts on Animal Behavior. Conserv. Biol. 2003, 17, 1785–1793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrari, M.C.O.; McCormick, M.I.; Meekan, M.G.; Simpson, S.D.; Nedelec, S.L.; Chivers, D.P. School is out on noisy reefs: The effect of boat noise on predator learning and survival of juvenile coral reef fishes. Proc. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 2018, 285, 20180033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- United Nations. The First Global Integrated Marine Assessment: World Ocean Assessment I; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2017; Available online: https://www.unep.org/resources/report/first-global-integrated-marine-assessment-world-ocean-assessment-i (accessed on 20 April 2022).

- Freitas, D.C.; dos Santos, J.E.A.; da Silva, P.C.M.; de Oliveira Lunardi, V.; Lunardi, D.G. Are dolphin-watching boats routes an effective tool for managing tourism in marine protected areas? Ocean Coast. Manag. 2021, 211, 105782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perez-Ortega, B.; Daw, R.; Paradee, B.; Gimbrere, E.; May-Collado, L.J. Dolphin-Watching Boats Affect Whistle Frequency Modulation in Bottlenose Dolphins. Front. Mar. Sci. 2021, 8, 618420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lusseau, D.; Higham, J.E.S. Managing the impacts of dolphin-based tourism through the definition of critical habitats: The case of bottlenose dolphins (Tursiops spp.) in Doubtful Sound, New Zealand. Tour. Manag. 2004, 25, 657–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toro, F.; Alacron, J.; Toro-Barros, B.; Mallea, G.; Capella, J.; Umaran-Young, C.; Abarca, P.; Lakestani, N.; Pena, C.; Alvarado-Rybak, M.; et al. Spatial and Temporal Effects of Whale Watching on a Tourism-Naive Resident Population of Bottlenose Dolphins (Tursiops truncatus) in the Humboldt Penguin National Reserve, Chile. Front. Mar. Sci. 2021, 8, 624974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, P.G.H. European Whales, Dolphins and Porpoises. Marine Mammal Conservation in Practice; Academic Press: London, UK; San Diego, CA, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wursig, B.; Evans, P.G.H. Cetaceans and Humans: Influences of Noise; Evans, P.G.H., Raga, J.A., Eds.; Marine Mammals; Springer: Boston, MA, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerra, M.; Dawson, S.M.; Brough, T.E.; Rayment, W.J. Effects of boats on the surface and acoustic behaviour of an endangered population of bottlenose dolphins. Endanger. Species Res. 2014, 24, 221–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Williams, R.; Cholewiak, D.; Clark, C.W.; Erbe, C.; George, C.; Lacy, R.; Leaper, R.; Moore, S.; New, L.; Parsons, C.; et al. Chronic ocean noise and cetacean population models. J. Cetacean Res. Manag. 2020, 21, 85–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Louis, M.; Simon-Bouhet, B.; Viricel, A.; Lucas, T.; Gally, F.; Cherel, Y.; Guinet, C. Evaluating the influence of ecology, sex and kinship on the social structure of resident coastal bottlenose dolphins. Mar. Biol. 2018, 165, 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, Y.J.J.; Mann, J. Dispersal, philopatry, and the role of fission-fusion dynamics in bottlenose dolphins. Mar. Mammal Sci. 2013, 29, 261–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connor, R.C.; Heithaus, M.R.; Barre, L.M. Complex social structure, alliance stability and mating access in a bottlenose dolphin ‘super-alliance’. Proc. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 2001, 268, 263–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- New, L.; Lusseau, D.; Harcourt, R. Dolphins and Boats: When Is a Disturbance, Disturbing? Front. Mar. Sci. 2020, 7, 353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- New, L.F.; Harwood, J.; Thomas, L.; Donovan, C.; Clark, J.S.; Hastie, G.; Thompson, P.M.; Cheney, B.; Scott-Hayward, L.; Lusseau, D. Modelling the biological significance of behavioural change in coastal bottlenose dolphins in response to disturbance. Funct. Ecol. 2013, 27, 314–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richardson, H. The Effect of Boat Disturbance on the Bottlenose Dolphin (Tursiops truncatus) of Cardigan Bay in Wales. Master’s Thesis, University College London, London, UK, 2012. Available online: https://www.seawatchfoundation.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2015/05/DISSERTATION-HRichardson.pdf (accessed on 20 April 2022).

- Au, W.W.L.; Green, M. Acoustic interaction of humpback whales and whale-watching boats. Mar. Environ. Res. 2000, 49, 469–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Constantine, R.; Brunton, D.H.; Dennis, T. Dolphin-watching tour boats change bottlenose dolphin (Tursiops truncatus) behaviour. Biol. Conserv. 2004, 117, 299–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lusseau, D.; Bejder, L. The Long-term Consequences of Short-term Responses to Disturbance Experiences from Whalewatching Impact Assessment. Int. J. Comp. Psychol. 2007, 20, 228–236. Available online: https://escholarship.org/uc/item/42m224qc (accessed on 20 April 2022).

- Papale, E.; Azzolin, M.; Giacoma, C. Boat traffic affects bottlenose dolphin (Tursiops truncatus) behaviour in waters surrounding Lampedusa Island, south Italy. J. Mar. Biol. Assoc. UK 2012, 92, 1877–1885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feingold, D.; Evans, P.G.H. Connectivity of Bottlenose Dolphins in Welsh Waters: North Wales Photo-Monitoring Report. 2014. Available online: https://www.seawatchfoundation.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2015/05/Feingold-Evans_2014b.pdf (accessed on 20 April 2022).

- Lohrengel, K.; Evans, P.G.H.; Lindenbaum, C.P.; Morris, C.W.; Stringell, T.B. Bottlenose Dolphin and Harbour Porpoise Monitoring in Cardigan Bay and Pen Llŷn a’r Sarnau Special Areas of Conservation, 2014–2016; NRW Evidence Report No: 191; Natural Resources Wales: Bangor, UK, 2017. Available online: https://cdn.naturalresources.wales/media/687852/eng-evidence-report-191-bottlenose-dolphin-monitoring-in-cardigan-bay-2014-2016.pdf (accessed on 20 April 2022).

- CCC (Ceredigion County Council); Countryside Council of Wales; Environment Agency Wales; North Western and North Wales Sea Fisheries Committee; Pembrokeshire Coast National Park Authority; Pembrokeshire County Council; South Wales Sea Fisheries Committee; Trinity House; Welsh Water. Cardigan Bay Special Area of Conservation (SAC) Management Scheme; Ceredigion County Council: Wales, UK, 2008; 179p.

- Hernandez, O.H. Economic Impacts of Sustainable Marine Tourism in the Local Economy. Case Study: Dolphin Watching Activity in New Quay, Cardigan, Wales. Ph.D. Thesis, Aberystwyth University, Aberystwyth, UK, 2015. Available online: https://pure.aber.ac.uk/portal/files/11409057/Garcia_Olga_upd.pdf (accessed on 20 April 2022).

- Welsh Government. Wales’ Marine Evidence Report. 2015. Available online: https://gov.wales/sites/default/files/publications/2018-05/wales-marine-evidence-report-wmer.pdf (accessed on 20 April 2022).

- Carlucci, R.; Manea, E.; Ricci, P.; Cipriano, G.; Fanizza, C.; Maglietta, R.; Gissi, E. Managing multiple pressures for cetaceans’ conservation with an Ecosystem-Based Marine Spatial Planning approach. J. Environ. Manag. 2021, 287, 112240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cummings, S.; Regeer, B.; de Haan, L.; Zweekhorst, M.; Bunders, J. Critical discourse analysis of perspectives on knowledge and the knowledge society within the Sustainable Development Goals. Dev. Policy Rev. 2018, 36, 727–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sachs, J.D.; Woo, W.T.; Yoshino, N.; Taghizadeh-Hesary, F. Importance of green finance for achieving sustainable development goals and energy security. In Handbook of Green Finance: Energy Security and Sustainable Development; Springer: Singapore, 2019; Volume 10, Available online: http://faculty.econ.ucdavis.edu/faculty/woo/Woo-Articles%20from%202012/Sachs-Woo-Yoshino-Farhad.2019.Green%20Finance.pdf (accessed on 20 April 2022).

- Govindan, K.; Shankar, K.M.; Kannan, D. Achieving sustainable development goals through identifying and analyzing barriers to industrial sharing economy: A framework development. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2020, 227, 107575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orams, M.B. Tourists getting close to whales, is it what whale-watching is all about? Tour. Manag. 2000, 21, 561–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higham, J.; Luck, M. Marine Wildlife and Tourism Management: Insights from the Natural and Social Sciences; CABI Publishing: Wallingford, UK, 2007; Available online: http://sherekashmir.informaticspublishing.com/718/1/9781845933456.pdf (accessed on 20 April 2022).

- Parsons, E.C.M. The Negative Impacts of Whale-Watching. J. Mar. Biol. 2012, 2012, 807294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Koroza, A. Habitat Use and Effects of Boat Traffic on Bottlenose Dolphins at New Quay Harbour, Cardigan Bay. Master’s Thesis, Bangor University, Anglesey, UK, 2018. Available online: https://www.seawatchfoundation.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2019/02/Koroza_Msc-thesis.pdf (accessed on 20 April 2022).

- Feingold, D.; Evans, P.G.H. Sea Watch Foundation Welsh Bottlenose Dolphin Photo-Identification Catalogue 2011; CCW Marine Monitoring Report. 2012. Available online: https://www.seawatchfoundation.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2017/01/2011_PHOTO-ID-CATALOGUE_Part-1.pdf (accessed on 20 April 2022).

- Bearzi, G.; Notarbartolo-di-Sciara, G.; Politi, E. Social Ecology of Bottlenose Dolphins in the Kvarneric (Northern Adriatic Sea). Mar. Mammal Sci. 1997, 13, 650–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shane, S.H.; Wells, R.S.; Wũrsig, B. Ecology, Behavior and Social Organization of the Bottlenose Dolphin: A Review. Mar. Mammal Sci. 1986, 2, 34–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hudson, T. Bottlenose Dolphin (Tursiops truncatus) Responses to Boat Activities in New Quay Bay. Master’s Thesis, Bangor University, Anglesey, UK, 2014. Available online: https://www.seawatchfoundation.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2015/05/Tess-Hudson-MSc-thesis.pdf (accessed on 20 April 2022).

- Dörler, D.; Fritz, S.; Voigt-Heucke, S.; Heigl, F. Citizen science and the role in sustainable development. Sustainability 2021, 13, 5676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gregory, P.R.; Rowden, A.A. Behaviour patterns of bottlenose dolphins (Tursiops truncatus) relative to tidal state, time-of-day, and boat traffic in Cardigan Bay, West Wales. Aquat. Mamm. 2001, 27, 105–113. [Google Scholar]

- Lepš, J.; Šmilauer, P. Biostatistics with R: An Introductory Guide for Field Biologists; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2020; pp. 239–241. [Google Scholar]

- Midway, S. Data Analysis in R. 2021. Available online: https://bookdown.org/steve_midway/DAR/from-science-to-data.html (accessed on 20 April 2022).

- University of Colorado Boulder. The General Linear Model (GLM): A Gentle Introduction. Available online: http://psych.colorado.edu/~carey/qmin/qminChapters/QMIN09-GLMIntro.pdf (accessed on 20 April 2022).

- Gardner, W.; Mulvey, E.P.; Shaw, E.C. Quantitaive methods in psychology. Regression Analyses of Counts and Rates: Poisson, Overdispersed Poisson, and Negative Binomial Models. Psychol. Bull. 1995, 118, 392–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piepho, H.P. Data transformation in statistical analysis of field trials with changing treatment variance. Agron. J. 2009, 101, 865–869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakagawa, S.; Schielzeth, H. Repeatability for Gaussian and non-Gaussian data: A practical guide for biologists. Biol. Rev. 2010, 85, 935–956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Hara, R.; Kotze, J. Do not log-transform count data. Nat. Proc. 2010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiao, Y.; Chen, Y.; Schneider, D.; Wroblewski, J. A simulation study of impacts of error structure on modeling stock-recruitment data using generalized linear models. Can. J. Fish. Aquat. Sci. 2004, 61, 122–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindé, A.; Mäntyniemi, S.; Mäntyniemi, M. Using the negative binomial distribution to model overdispersion in ecological count data. Ecology 2011, 92, 1414–1421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beard, E.; Marsden, J.; Brown, J.; Tombor, I.; Stapleton, J.; Michie, S.; West, R. Understanding and using time series analyses in addiction research. Addiction 2019, 114, 1866–1884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, F.J.; de Santana, D.G.; Sampaio, M.V. Modeling Overdispersion, Autocorrelation, and Zero-Inflated Count Data Via Generalized Additive Models and Bayesian Statistics in an Aphid Population Study. Neotrop. Entomol. 2020, 49, 40–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vergara-Peña, A. The Effects of Marine Tourism on Bottlenose Dolphins in Cardigan Bay. Ph.D. Thesis, Bangor University, Anglesey, UK, 2019. Available online: https://research.bangor.ac.uk/portal/files/34707125/Vergara_Pena_thesis_2020A.Vergara_Pen_a_Thesis_2020July_1.pdf (accessed on 20 April 2022).

- Pierpoint, C.; Allan, L.; Arnold, H.; Evans, P.G.H.; Perry, S.; Wilberforce, L.; Baxter, J. Monitoring important coastal sites for bottlenose dolphin in Cardigan Bay, UK. J. Mar. Biol. Assoc. UK 2009, 89, 1033–1043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pierpoint, C.; Allan, L. Bottlenose dolphins and boat traffic on the Ceredigion coast, West Wales. In Department of Environmental Services and Housing, Cyngor Sir Ceredigion County Council; Penmorfa: Aberaeron, UK, 2006; Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/279173602 (accessed on 20 April 2022).

- La Manna, G.; Manghi, M.; Pavan, G.; lo Mascolo, F.; Sarà, G. Behavioural strategy of common bottlenose dolphins (Tursiops truncatus) in response to different kinds of boats in the waters of Lampedusa Island (Italy). Aquat. Conserv. Mar. Freshw. Ecosyst. 2013, 23, 745–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pennino, M.G.; Amparo Pérez Roda, M.; Pierce, G.J.; Rotta, A. Effects of vessel traffic on relative abundance and behaviour of cetaceans: The case of the bottlenose dolphins in the Archipelago de La Maddalena, north-western Mediterranean sea. Hydrobiologia 2016, 776, 237–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Baş, A.A.; Amaha Öztürk, A.; Öztürk, B. Selection of critical habitats for bottlenose dolphins (Tursiops truncatus) based on behavioral data, in relation to marine traffic in the Istanbul Strait, Turkey. Mar. Mammal Sci. 2015, 31, 979–997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inman, A.; Brooker, E.; Dolman, S.; McCann, R.; Wilson, A.M.W. The use of marine wildlife-watching codes and their role in managing activities within marine protected areas in Scotland. Ocean Coast. Manag. 2016, 132, 132–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lissner, I.; Mayer, M. ‘Tourists’ willingness to pay for Blue Flag’s new ecolabel for sustainable boating: The case of whale-watching in Iceland. Scand. J. Hosp. Tour. 2020, 20, 352–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garrod, B.; Fennell, D.A. An Analysis of whalewatching codes of conduct. Ann. Tour. Res. 2004, 31, 334–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duprey, N.M.T.; Weir, J.S.; Würsig, B. Effectiveness of a voluntary code of conduct in reducing vessel traffic around dolphins. Ocean. Coast. Manag. 2008, 51, 632–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rocha, D.; Drakeford, B.; Marley, S.A.; Potts, J.; Hale, M.; Gullan, A. Moving towards a sustainable cetacean-based tourism industry—A case study from Mozambique. Mar. Policy 2020, 120, 104048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, J.C.; Vasconcelos, L.; Monteiro, R.; Silva, F.Z.; Duarte, C.M.; Ferreira, F. Ocean literacy to promote sustainable development goals and agenda 2030 in coastal communities. Educ. Sci. 2021, 11, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwatra, S.; Kumar, A.; Sharma, P. A critical review of studies related to construction and computation of Sustainable Development Indices. Ecol. Indic. 2020, 112, 106061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsalis, T.A.; Malamateniou, K.E.; Koulouriotis, D.; Nikolaou, I.E. New challenges for corporate sustainability reporting: United Nations’ 2030 Agenda for sustainable development and the sustainable development goals. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2020, 27, 1617–1629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Code | Definition | Compliance with Code |

|---|---|---|

| Y1 | Passing cetaceans with no-wake speed or no rapid changes in course. | Compliant |

| Y2 | The boat slows down and stops in the presence of dolphins. | Compliant |

| N1 | The boat does not slow down within 300 m of dolphins. | Non-compliant |

| N2 | Following dolphins by rapid changes in course and speed. | Non-compliant |

| N3 | Following, touching, or feeding dolphins. | Non-compliant |

| R | A boat is a boat with permission under license from CCC (boats under flag when under research) | Compliant |

| Variable | Coeff ± SE |

|---|---|

| 2010 | As reference |

| 2011 | 0.07 ± 0.33 |

| 2012 | 0.71 ± 2.04 |

| 2013 | 0.73 ± 0.31 |

| 2014 | 0.33 ± 0.29 |

| 2015 | 0.82 ± 0.32 |

| 2016 | 0.13 ± 0.33 |

| 2017 | 0.82 ± 0.34 |

| 2018 | 1.30 ± 0.35 |

| Variable | Coeff ± SE |

|---|---|

| YA | As reference |

| FI | 0.01 ± 0.67 |

| VPB | 0.0005 ± 0.72 |

| sMB | 7.32 × 10−8 ± 1.35 |

| RB | 9.56 × 10−7 ± 1.43 |

| SB | 1.10 × 10−15 ± 2.47 |

| Variable | Coeff ± SE |

|---|---|

| VIK | As reference |

| E5 | 1.02 ± 0.57 |

| E6 | 1.016 ± 0.55 |

| ISL | 1.451 ± 0.57 |

| SUL | 1.60 ± 0.61 |

| DUN | 1.51 ± 0.67 |

| ANN | 1.57 ± 0.76 |

| ORCA | 1.72 ± 0.87 |

| Variable | Coeff ± SE |

|---|---|

| SB | As reference |

| RB | 0.32 ± 0.13 |

| sMB | 0.59 ± 0.12 |

| mMB | 0.71 ± 0.35 |

| FI | 0.94 ± 0.16 |

| YA | 1.09 ± 0.15 |

| VPB | 2.68 ± 0.13 |

| Variable | Coeff ± SE |

|---|---|

| Negative | As reference |

| Positive | 1.78 ± 0.20 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Koroza, A.; Evans, P.G.H. Bottlenose Dolphin Responses to Boat Traffic Affected by Boat Characteristics and Degree of Compliance to Code of Conduct. Sustainability 2022, 14, 5185. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14095185

Koroza A, Evans PGH. Bottlenose Dolphin Responses to Boat Traffic Affected by Boat Characteristics and Degree of Compliance to Code of Conduct. Sustainability. 2022; 14(9):5185. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14095185

Chicago/Turabian StyleKoroza, Aleksandra, and Peter G. H. Evans. 2022. "Bottlenose Dolphin Responses to Boat Traffic Affected by Boat Characteristics and Degree of Compliance to Code of Conduct" Sustainability 14, no. 9: 5185. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14095185

APA StyleKoroza, A., & Evans, P. G. H. (2022). Bottlenose Dolphin Responses to Boat Traffic Affected by Boat Characteristics and Degree of Compliance to Code of Conduct. Sustainability, 14(9), 5185. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14095185