Understanding Household Vulnerability and Relative Poverty in Forestry Transition: A Study on Forestry-Worker Families in China’s Greater Khingan Mountains State-Owned Forest Region

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Vulnerability

2.2. Poverty

2.3. Life and Job Satisfaction

3. Data and Methods

3.1. Data Source and Description

3.2. Identifying Household Vulnerability Indicators

3.3. Determining Household Vulnerability Indicator Weights

3.4. Method for Evaluating Household Vulnerability

3.5. Method for Estimating Relative Poverty

4. Results

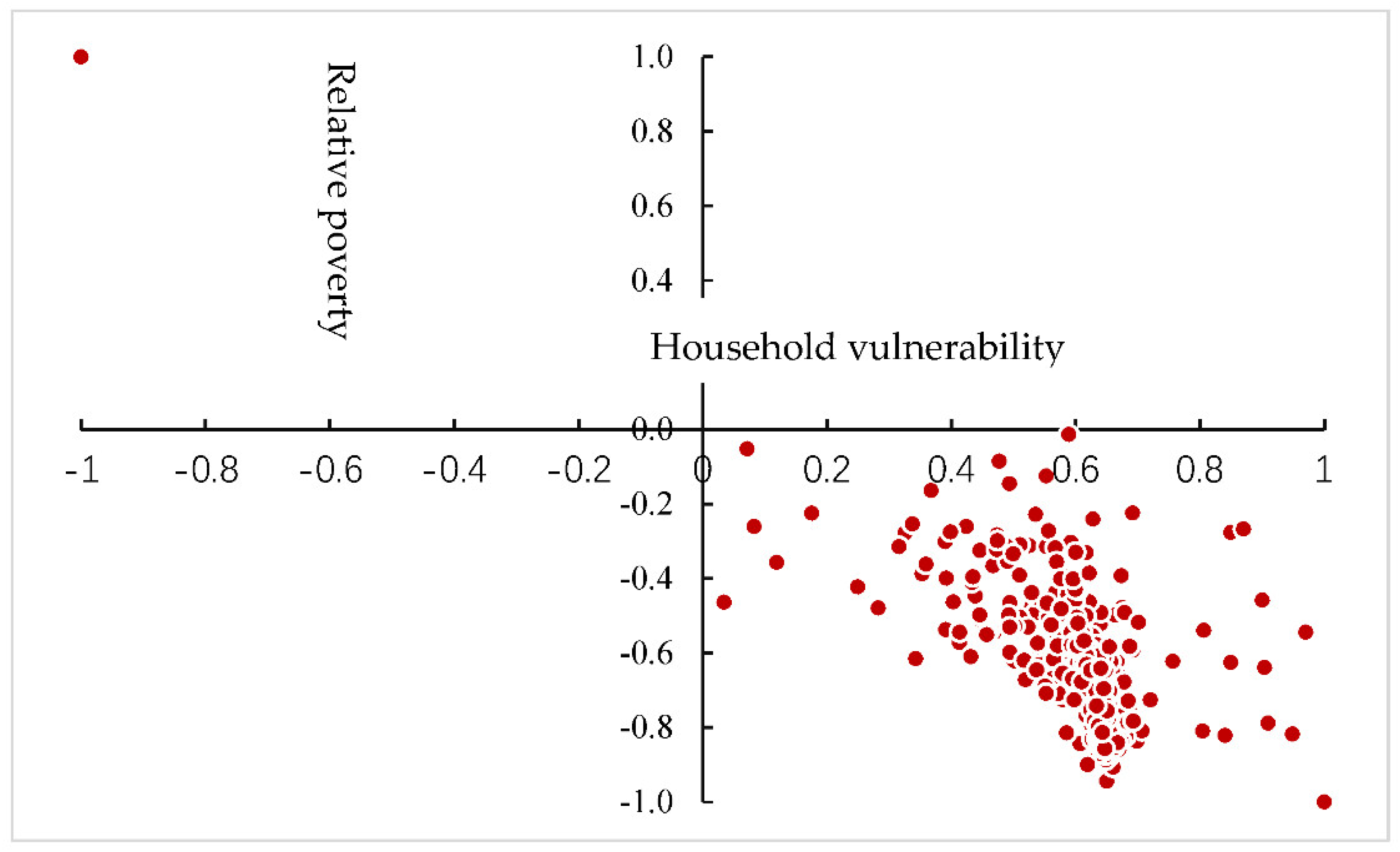

4.1. Results of Measured Household Vulnerability and Relative Poverty

4.2. Diagnosing the Influential Factors of Household Vulnerability and Relative Poverty

5. Discussion

5.1. Interpretation of the Vulnerability–Poverty Relationship

5.2. Effects of the Potential Factors on Household Vulnerability and Relative Poverty

6. Conclusions and Policy Implications

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Variables | Max | Min | Median | Average | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Life satisfaction | Current life attitude | 5.00 | 0.00 | 3.00 | 3.11 | |

| Current life confidence | 5.00 | 0.00 | 4.00 | 3.66 | ||

| Job satisfaction | Working conditions and content | Working facility equipment | 5.00 | 1.00 | 4.00 | 3.52 |

| Working environment | 5.00 | 1.00 | 4.00 | 3.80 | ||

| Degree of work engagement | 5.00 | 1.00 | 4.00 | 3.60 | ||

| Calculation and payment system of overtime wages | 5.00 | 1.00 | 2.00 | 2.52 | ||

| Working stability | 5.00 | 1.00 | 4.00 | 4.04 | ||

| Match status of income and workload | 5.00 | 1.00 | 3.00 | 2.89 | ||

| Working rewards and self-actualization | Rewards for outstanding work | 5.00 | 1.00 | 4.00 | 3.41 | |

| Sense of achievement | 5.00 | 1.00 | 4.00 | 3.80 | ||

| Opportunity to be an important role in the group | 5.00 | 1.00 | 4.00 | 3.41 | ||

| Opportunities to give full play to their abilities | 5.00 | 1.00 | 4.00 | 3.65 | ||

| Opportunity to independently decide how to complete the work | 5.00 | 1.00 | 4.00 | 3.67 | ||

| Promotion opportunities | 5.00 | 1.00 | 3.00 | 3.02 | ||

| Enterprise culture and working atmosphere | The actual situation of the unit | 5.00 | 1.00 | 4.00 | 3.95 | |

| Corresponding status of unit authority | 5.00 | 1.00 | 4.00 | 3.54 | ||

| The way unit leaders treat | 5.00 | 1.00 | 4.00 | 4.06 | ||

| Ability to lead emergency decisions | 5.00 | 1.00 | 4.00 | 4.16 | ||

| Unit policy implementation | 5.00 | 1.00 | 4.00 | 4.02 | ||

| The way colleagues get along with each other | 5.00 | 2.00 | 4.00 | 4.15 | ||

References

- Li, C.H.; Sun, D.; Wang, Z.W. Driving and Obstacle Factors for Industrial Transition Performance of State-owned Forest Regions in Daxing’an and Xiaoxing’an Mountains. J. Northeast For. Univ. 2020, 48, 133–138. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, H.G.; Hu, S.L.; Ren, X.M.; Cao, Y.K. Determinants of engagement in non–timber forest products (NTFPs) business activities: A study on worker households in the forest areas of Daxinganling and Xiaoxinganling Mountains, northeastern China. For. Policy Econ. 2017, 80, 125–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Wen, H.; Wang, K.; Sun, J.X.; Yu, J.H.; Wang, Q.G.; Wang, W.J. Forest plant and macrofungal differences in the Greater and Lesser Khingan Mountains in Northeast China: A regional–historical comparison and its implications. J. For. Res. 2021, 33, 623–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Yue, C.; Wei, X.; Blanco, J.A.; Trancoso, R. Tree profile equations are significantly improved when adding tree age and stocking degree: An example for Larix gmelinii in the Greater Khingan Mountains of Inner Mongolia, northeast China. Eur. J. For. Res. 2020, 139, 443–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, J.J.; Wang, Y.F.; Chen, H. Evaluation and Difference Analysis of Transformation Ability of Forest Industry Groups in the Key State-owned Forest Regions. J. Agro-For. Econ. Manag. 2020, 19, 77–86. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Geng, Y.D.; Wan, Z.F.; Li, W.; Liu, M. Study on Process and Policies of the Reform of Stated–owned Forest Regions—Based on the Investigations on Forestry Industrial Group of Longjiang and Forestry Group of Daxing’anling Region. For. Econ. 2017, 2, 3–11. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Lv, J.H.; Liu, Y.D.; Zhang, B. Analysis on Forestry Industry Integration Degree and Its Influencing Factors—A Case Study of State-owned Forest Regions in Heilongjiang Province. For. Econ. 2018, 5, 60–64, 90. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Ke, S.F.; Qiao, D.; Zhang, X.X.; Feng, Q.Y. Corrigendum to “Changes of China’s forestry and forest products industry over the past 40 years and challenges lying ahead”. For. Policy Econ. 2020, 123, 102351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, F.; Zhao, Y. Determinants and Differences of Grain Production Efficiency Between Main and Non–Main Producing Area in China. Sustainability 2019, 11, 5225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Wu, Y.; Song, M.; Zhu, Z. Stochastic frontier analysis of productive efficiency in China’s Forestry Industry. J. For. Econ. 2017, 28, 87–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, L.; Wang, Y.; Su, D.; Zhou, L.; Yu, D.; Lewis, B.J.; Qi, L. Major Forest Types and the Evolution of Sustainable Forestry in China. Environ. Manag. 2011, 48, 1066–1078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, M.; Qi, Y.; Gong, P. China’s new forest policy. Science 2000, 289, 2049–2050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J. Forestry development and forest policy in China. J. For. Econ. 2005, 10, 159–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.L.; Xu, J.T. Livelihood mushroomed: Examining household level impacts of non-timber forest products under new management regime in China’s state forests. For. Policy Econ. 2019, 98, 44–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lo, K. Authoritarian environmentalism, just transition, and the tension between environmental protection and social justice in China’s forestry reform. For. Policy Econ. 2021, 131, 102574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Chen, S. Wood trade responses to ecological rehabilitation program: Evidence from China’s new logging ban in natural forests. For. Policy Econ. 2021, 122, 102339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, H.; Hou, F.; Yang, Y.; Han, Z.; Liu, C. An assessment of the international competitiveness of China’s forest products industry. For. Policy Econ. 2020, 119, 102256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhang, T.; Zeng, Y.X.; Cheng, B.D.; Li, H.X. Designating National Forest Cities in China: Does the policy improve the urban living environment? For. Policy Econ. 2021, 125, 102400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguilar, F.X.; Wen, Y. Socio–economic and ecological impacts of China’s forest sector policies. For. Policy Econ. 2021, 217, 1024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Z.F.; Cao, Y.K. Loss of Social Welfare in Forest Resource–based Economic Transformation, Characteristics, Contents, and Outlets. World For. Res. 2017, 2, 67–72. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Gautam, Y.; Andersen, P. Rural livelihood diversification and household well–being: Insights from Humla, Nepal. J. Rural Stud. 2016, 44, 239–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panthi, J.; Aryal, S.; Dahal, P.; Bhandari, P.; Krakauer, N.Y.; Pandey, V.P. Livelihood vulnerability approach to assessing climate change impacts on mixed agro–livestock smallholders around the Gandaki River Basin in Nepal. Reg. Environ. Chang. 2016, 16, 1121–1132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salik, K.M.; Jahangir, S.; ul Hasson, S. Climate change vulnerability and adaptation options for the coastal communities of Pakistan. Ocean. Coast. Manag. 2015, 112, 61–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, K.U.; Dulal, H.B.; Johnson, C.; Baptiste, A. Understanding livelihood vulnerability to climate change: Applying the livelihood vulnerability index in Trinidad and Tobago. Geoforum 2013, 47, 125–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Zhang, H.P.; Xu, J.T. Effects of Key State-owned Forestry Reforms on the Inequality of Household Incomes. World For. Res. 2016, 5, 48–53. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Rowntree, B.S. Poverty, a study of town life. Charity Organ. Rev. 1902, 11, 260–266. [Google Scholar]

- Townsend, P.; Phillimore, P.; Beattie, A. Health and deprivation. Inequality and the North. Rev. Cuba. Hig. Epidemiol. 2004, 35, 48–50. [Google Scholar]

- Van, O.V.; Wang, C. Social investment and poverty reduction, a comparative analysis across fifteen European countries. J. Soc. Policy 2015, 44, 611–638. [Google Scholar]

- Hahn, M.B.; Riederer, A.M.; Foster, S.O. The Livelihood Vulnerability Index: A pragmatic approach to assessing risks from climate variability and change—A case study in Mozambique. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2009, 19, 74–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandey, R.; Bardsley, D.K. Social-ecological vulnerability to climate change in the Nepali Himalaya. Appl. Geogr. 2015, 64, 74–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azzam, A.M.; Rettab, B. A welfare measure of consumer vulnerability to rising prices of food imports in the UAE. Food Policy 2012, 5, 554–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiao, X.; Pouliot, M.; Walelign, S.Z. Livelihood strategies and dynamics in rural Cambodia. World Dev. 2017, 97, 266–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foster, J.J.; Greer, E.; Thorbecke, E. A Class of Decomposable Poverty Measures. Econometrica 1984, 52, 761–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suryahadi, A.; Sumarto, S. Poverty and vulnerability in Indonesia before and after the economic crisis. Asian Econ. J. 2003, 17, 45–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakravarty, S.R. A New Index of Poverty. In Poverty, Social Exclusion and Stochastic Dominance; Themes in Economics; Springer: Singapore, 2019; pp. 31–37. [Google Scholar]

- White, G.F. Natural Hazards, 1st ed.; Oxford University Press: London, UK, 1974. [Google Scholar]

- Mackay, A. Climate change 2007, impacts, adaptation and vulnerability. Contribution of working group ii to the fourth assessment report of the intergovernmental panel on climate change. J. Environ. Qual. 2007, 37, 2407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.Y.; Liu, Y.; Ma, L.; He, S.F. Review on the Theoretical Model and Assessment Framework of Foreign Vulnerability Research. Areal Res. Dev. 2012, 31, 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Bhattacharjee, K.; Behera, B. Determinants of household vulnerability and adaptation to floods: Empirical evidence from the Indian State of West Bengal. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2018, 31, 758–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, M.; Ghosal, S. Determinants of household livelihood vulnerabilities to climate change in the Himalayan foothills of West Bengal, India. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2020, 50, 2–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ligon, E.; Schechter, L. Measuring vulnerability. Econ. J. 2003, 113, 95–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asif, I.; Ronald, C.E.; Hallie, E.; Jagadish, P.; Yasin, W.R. IPCC’s current conceptualization of ‘vulnerability’ needs more clarification for climate change vulnerability assessments. J. Environ. Manag. 2022, 303, 114246. [Google Scholar]

- Baffoe, G.; Matsuda, H. An Empirical Assessment of Households’ Livelihood Vulnerability: The Case of Rural Ghana. Soc. Indic. Res. 2017, 140, 1225–1257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoq, M.S.; Raha, S.K.; Hossain, M.I. Livelihood Vulnerability to Flood Hazard: Understanding from the Flood–prone Hoar Ecosystem of Bangladesh. Environ. Manag. 2021, 67, 532–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oberlack, C.; Tejada, L.; Messerli, P.; Rist, S.; Giger, M. Sustainable livelihoods in the global land rush? Archetypes of livelihood vulnerability and sustainability potentials. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2016, 41, 153–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huong, N.T.L.; Yao, S.; Fahad, S. Assessing household livelihood vulnerability to climate change: The case of Northwest Vietnam. Hum. Ecol. Risk Assess. 2019, 25, 1157–1175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eze, J.N.; Aliyu, U.; Alhaji–Baba, A.; Alfa, M. Analysis of farmers’ vulnerability to climate change in Niger state, Nigeria. Soc. Sci. Electron. Publ. 2018, 82, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brooks, N.; Adger, W.N.; Kelly, P.M. The determinants of vulnerability and adaptive capacity at the national level and the implications for adaptation. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2005, 15, 151–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, V.T.; An-Vo, D.-A.; Cockfield, G.; Mushtaq, S. Assessing Livelihood Vulnerability of Minority Ethnic Groups to Climate Change: A Case Study from the Northwest Mountainous Regions of Vietnam. Sustainability 2021, 13, 7106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alkire, S.; Foster, J. Counting and multidimensional poverty measurement. J. Public Econ. 2007, 95, 476–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, F.; Chen, S.; Dabalen, A.; Dikhano, Y.; Hamadeh, N.; Jolliffe, D.; Narayan, A.; Prydz, E.B.; Revenga, A.; Sangraula, P.; et al. A Global Count of the Extreme Poor in 2012: Data Issues, Methodology and Initial Results. Soc. Sci. Electron. Publ. 2016, 14, 141–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Booth, C. Life and Labor of the People in London; Macmillan: London, UK, 1892. [Google Scholar]

- Group, W.B. A Measured Approach to Ending Poverty and Boosting Shared Prosperity: Concepts, Data, and the Twin Goals; The World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Group, W.B. Poverty and Shared Prosperity 2018: Piecing Together the Poverty Puzzle; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Commission European. Portfolio of Indicators for the Monitoring of the European Strategy for Social Protection and Social Inclusion; European Commission: Brussel, Belgium, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, B. Statistical inference for poverty measures with relative poverty lines. J. Econ. 2004, 101, 337–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Decerf, B. Combining absolute and relative poverty: Income poverty measurement with two poverty lines. Soc. Choice Welf. 2020, 56, 325–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diener, E.; Emmons, R.A.; Larsen, R.J.; Griffin, S. The Satisfaction with Life Scale. J. Personal. Assess. 1985, 49, 71–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shin, D.C.; Johnson, D.M. Avowed happiness as an overall assessment of the quality of life. Soc. Indic. Res. 1978, 5, 475–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Wu, Y.; Jiang, S.; Zhai, H.Z. WeChat Addiction Suppresses the Impact of Stressful Life Events on Life Satisfaction. Cyberpsychol. Behav. Soc. Netw. 2018, 21, 194–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blatný, M.; Květon, P.; Šolcová, I.; Zábrodská, K.; Mudrák, J.; Jelínek, M.; Machovcová, K. The Influence of Personality Traits on Life Satisfaction through Work Engagement and Job Satisfaction among Academic Faculty Members. Studia Psychol. 2018, 60, 274–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheung, C.K.; Leung, K. Ways that Social Change Predicts Personal Quality of Life. Soc. Indic. Res. 2010, 96, 459–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grogan, R.H.; Aschebrook–Kilfoy, B.; Angelos, P. Interventions to improve thyroid cancer survivors’ quality of life. Future Oncol. 2016, 12, 1309–1311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanley, S.M.; Ragan, E.P.; Rhoades, G.K.; Markman, J.H. Examining changes in relationship adjustment and life satisfaction in marriage. J. Fam. Psychol. 2012, 26, 165–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Audenaert, M.; George, B.; Bauwens, R.; Decuypere, A.; Descamps, A.; Muylaert, J.; Ma, R.; Decramer, A. Empowering leadership, social support, and job crafting in public organizations: A multilevel study. Public Pers. Manag. 2020, 49, 367–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Togia, A.; Koustelios, A.; Tsigilis, N. Job satisfaction among Greek academic librarians. Libr. Inf. Sci. Res. 2004, 26, 373–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakotic, D. Relationship between job satisfaction and organizational performance. Econ. Res. 2016, 29, 118–130. [Google Scholar]

- Kimura, T. Causal Relationship between Job Satisfaction and Organizational Performance. J. Sci. Labour 2011, 35, 1265–1276. [Google Scholar]

- Alegre, I.; Mas–Machuca, M.; Berbegal–Mirabent, J. Antecedents of employee job satisfaction: Do they matter? J. Bus. Res. 2016, 69, 1390–1395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ireri, K. High Job Satisfaction Despite Low Income: A National Study of Kenyan Journalists. J. Mass Commun. Q. 2016, 93, 164–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schyns, B.; Croon, M.A. A model of task demands, social structure, and leader-member exchange and their relationship to job satisfaction. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2006, 4, 602–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Boswell, W.R.; Boudeau, J.W. Employee satisfaction with performance appraisals and appraisers: The role of perceived appraisal use. Hum. Resour. Dev. Q. 2000, 3, 283–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Hu, B.; Qiu, M. Job satisfaction as a mediator in the relationship between performance appraisal and voice behavior. Soc. Behav. Personal. Int. J. 2014, 8, 1315–1323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Ghiselli, R.; Law, R.; Ma, J. Motivating frontline employees: Role of job characteristics in work and life satisfaction. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2016, 27, 27–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mabasa, F.D.; Ngirande, H. Perceived organizational support influences on job satisfaction and organizational commitment among junior academic staff members. J. Psychol. Afr. 2015, 25, 364–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, G.S.; Premalatha, K. Securing private information by data perturbation using statistical transformation with three–dimensional shearing. Appl. Soft Comput. 2021, 112, 107819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ufumaka, I. Comparative Analysis of Machine Learning Algorithms for Heart Disease Prediction. Int. J. Sci. Res. 2021, 11, 339–346. [Google Scholar]

- Delgado, A.; Romero, I. Environmental conflict analysis using an integrated grey clustering and entropy–weight method: A case study of a mining project in Peru. Environ. Model. Softw. 2016, 77, 108–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.-W.; Li, E.-Q.; Sun, Y.-Y.; Dong, B.-T. Research on the operation safety evaluation of urban rail stations based on the improved TOPSIS method and entropy weight method. J. Rail Transp. Plan. Manag. 2021, 20, 100262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Explanatory Variable | Number of Households | Proportion | Explanatory Variable | Number of Households | Proportion |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of household members | Number of insurance fund | ||||

| 1 | 12 | 3.34 | 0 | 8 | 2.23 |

| 2 | 62 | 17.27 | 1 | 9 | 2.51 |

| 3 | 242 | 67.41 | 2 | 7 | 1.95 |

| 4 | 32 | 8.91 | 3 | 5 | 1.39 |

| 5 | 9 | 2.51 | 4 | 8 | 2.23 |

| 6 | 2 | 0.56 | 5 | 84 | 23.40 |

| Gender of household head | 6 | 238 | 66.30 | ||

| Female (0) | 44 | 12.26 | Bank deposit | ||

| Male (1) | 315 | 87.74 | Less than or equal to CNY 10,000 | 238 | 66.29 |

| Age of household head | Greater than CNY 10,000 and less than or equal to CNY 30,000 | 64 | 17.83 | ||

| ≤30 | 29 | 8.08 | Greater than CNY 30,000 and less than or equal to CNY 50,000 | 29 | 8.08 |

| 31–40 | 74 | 20.61 | Greater than CNY 50,000 and less than or equal to CNY 100,000 | 14 | 3.90 |

| 41–50 | 202 | 56.27 | Greater than CNY 100,000 | 14 | 3.90 |

| 51–60 | 48 | 13.37 | Loan amount | ||

| >60 | 6 | 1.67 | Less than or equal to CNY 10,000 | 322 | 89.69 |

| Health status of household head | Greater than CNY 10,000 and less than or equal to CNY 30,000 | 13 | 3.62 | ||

| 1. Very poor | 14 | 3.90 | Greater than CNY 30,000 and less than or equal to CNY 50,000 | 15 | 4.18 |

| 2. Poor | 22 | 6.13 | Greater than CNY 50,000 and less than or equal to CNY 100,000 | 7 | 1.95 |

| 3. Fair | 161 | 44.85 | Greater than CNY 100,000 | 2 | 0.56 |

| 4. Good | 117 | 32.59 | Debt amount | ||

| 5. Very good | 45 | 12.53 | Less than or equal to CNY 10,000; | 327 | 91.09 |

| Educational level of household head (years) | Greater than CNY 10,000 and less than or equal to CNY 30,000 | 12 | 3.34 | ||

| ≤6 | 8 | 2.23 | Greater than CNY 30,000 and less than or equal to CNY 50,000 | 11 | 3.06 |

| 7–9 | 81 | 22.56 | Greater than CNY 50,000 and less than or equal to CNY 100,000 | 7 | 1.95 |

| 10–12 | 116 | 32.31 | Greater than CNY 100,000 | 2 | 0.56 |

| ≥13 | 154 | 42.90 | Life satisfaction | ||

| Marital status | ≤5 | 53 | 14.76 | ||

| 1. Married | 317 | 88.30 | 5–10 | 306 | 85.24 |

| 2. Divorced | 21 | 5.85 | Work condition and comfortability | ||

| 3. Widowed | 13 | 3.62 | ≤10 | 27 | 7.52 |

| 4. Unmarried | 8 | 2.23 | 11–20 | 55 | 15.32 |

| Working status of household head | 21–30 | 277 | 77.16 | ||

| 1. On the register and on duty | 296 | 82.45 | Work reward and self-accomplishment | ||

| 2. On the register but not on duty | 8 | 2.23 | ≤10 | 21 | 5.85 |

| 3. Not on the register and on duty | 37 | 10.31 | 11–20 | 38 | 10.58 |

| 4. Other | 18 | 5.01 | 21–30 | 300 | 83.57 |

| Whether household head is compensated by the one-off resettlement program | Enterprise culture and working atmosphere | ||||

| 0. No | 343 | 95.54 | ≤10 | 40 | 11.14 |

| 1. Yes | 16 | 4.46 | 11–20 | 46 | 12.81 |

| 21–30 | 273 | 76.04 |

| Component | Indicator | Max (CNY) | Min (CNY) | Median (CNY) | Average (CNY) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Exposure (basic rigid requirements) | Food expenditure | 60,000.00 | 1000.00 | 18,000.00 | 18,138.54 |

| Clothing expenditure | 30,000.00 | 0.00 | 4000.00 | 4998.26 | |

| Education expenditure | 120,000.00 | 0.00 | 4000.00 | 9340.70 | |

| Commodity expenditure | 20,000.00 | 0.00 | 2000.00 | 2384.66 | |

| Living expenditure | 50,000.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 436.76 | |

| Direct medical expenditure | 70,000.00 | 0.00 | 2000.00 | 4788.97 | |

| Household production and operating expenditure | 51,000.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 820.46 | |

| Sensitivity (resilient demand affected by the incident) | Transportation and communication expenditure | 55,800.00 | 120.00 | 2680.00 | 3488.10 |

| Cultural and entertainment expenditure | 100,000.00 | 0.00 | 300.00 | 1869.43 | |

| Household equipment supplies and service expenditure | 220,000.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 4730.03 | |

| Health/fitness/beauty expenditure | 12,000.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 549.79 | |

| Transfer expenditure | 100,000.00 | 0.00 | 5000.00 | 7326.46 | |

| Adaptability | Subtotal of salary income | 151,500.00 | 0.00 | 46,000.00 | 50,922.31 |

| Subtotal of household business income | 130,000.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 3841.78 | |

| Subtotal of transferable income | 80,000.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 6501.26 | |

| Subtotal of property income | 210,200.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 1213.15 | |

| Other income | 30,000.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 523.68 |

| Component | Indicator | Weight |

|---|---|---|

| Exposure (basic rigid requirements) | Food expenditure | 0.1577 |

| Clothing expenditure | 0.1489 | |

| Education expenditure | 0.1253 | |

| Commodity expenditure | 0.1421 | |

| Living expenditure | 0.1582 | |

| Direct medical expenditure | 0.1598 | |

| Household production and operating expenditure | 0.1080 | |

| Sensitivity (resilient demand affected by the incident) | Transportation and communication expenditure | 0.2836 |

| Cultural and entertainment expenditure | 0.1637 | |

| Household equipment supplies and service expenditure | 0.1222 | |

| Health/fitness/beauty expenditure | 0.1683 | |

| Transfer expenditure | 0.2622 | |

| Adaptability | Subtotal of salary income | 0.4021 |

| Subtotal of household business income | 0.1389 | |

| Subtotal of transferable income | 0.2559 | |

| Subtotal of property income | 0.1542 | |

| Other income | 0.0489 |

| Sub-Region | Total | V > 0 | V < 0 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sub-Total | p > 0 | p < 0 | Sub-Total | p > 0 | p < 0 | ||

| A’muer | 48 | 48 | 0 | 48 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Genhe | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Hanjiayuan | 15 | 15 | 0 | 15 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Huzhong | 18 | 17 | 0 | 17 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Jiagedaqi | 19 | 19 | 0 | 19 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Mangui | 3 | 3 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Shibazhan | 49 | 49 | 0 | 49 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Songling | 53 | 52 | 0 | 52 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Suileng | 16 | 16 | 0 | 16 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Tahe | 48 | 48 | 1 | 47 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Tuqiang | 13 | 13 | 0 | 13 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Xijilin | 19 | 19 | 0 | 19 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Xinlin | 54 | 54 | 0 | 54 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Yitulihe | 3 | 3 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Total | 358 | 357 | 1 | 356 | 2 | 2 | 0 |

| Dimension | Variables | Household Vulnerability | Relative Poverty |

|---|---|---|---|

| Household characteristics | Number of household members | −0.1550 ** | 0.3590 ** |

| (0.0741) | (0.1390) | ||

| Gender of household head | −0.2230 * | 0.2600 *** | |

| (0.1290) | (0.0858) | ||

| Age of household head | −0.0257 *** | 0.00638 | |

| (0.0065) | (0.0076) | ||

| Health status of household head | −0.0640 | 0.1290 ** | |

| (0.0496) | (0.0505) | ||

| Education years of household head | −0.0194 | 0.0168 | |

| (0.0133) | (0.0132) | ||

| Marital status | 0.0468 | 0.0110 | |

| (0.0896) | (0.0711) | ||

| Working status of household head | −0.0929 | 0.1650 *** | |

| (0.0621) | (0.0431) | ||

| Whether household head is compensated by the one-off resettlement program | −0.0045 | 0.2260 | |

| (0.1900) | (0.2790) | ||

| Financial status | Number of insurance funds | −0.0551 | 0.0784 * |

| (0.0429) | (0.0432) | ||

| Bank deposit | −0.0675 *** | 0.1090 *** | |

| (0.0252) | (0.0257) | ||

| Loan amount | −0.00420 | 0.0171 | |

| (0.0552) | (0.0442) | ||

| Debt amount | 0.1240 * | 0.0219 | |

| (0.0730) | (0.0666) | ||

| Life and job satisfaction | Life satisfaction | −0.1450 *** | 0.0858 *** |

| (0.0295) | (0.0240) | ||

| Work condition and comfortability | 0.0358 *** | −0.0280 ** | |

| (0.0104) | (0.0124) | ||

| Work reward and self-accomplishment | −0.0682 *** | 0.0136 | |

| (0.0107) | (0.0103) | ||

| Enterprise culture and working atmosphere | −0.0045 | 0.0241 ** | |

| (0.0113) | (0.0105) | ||

| Observations | 359 | 359 | |

| R-squared | 0.4100 | 0.3730 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Chen, H.; Cao, J.; Zhu, H.; Wang, Y. Understanding Household Vulnerability and Relative Poverty in Forestry Transition: A Study on Forestry-Worker Families in China’s Greater Khingan Mountains State-Owned Forest Region. Sustainability 2022, 14, 4936. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14094936

Chen H, Cao J, Zhu H, Wang Y. Understanding Household Vulnerability and Relative Poverty in Forestry Transition: A Study on Forestry-Worker Families in China’s Greater Khingan Mountains State-Owned Forest Region. Sustainability. 2022; 14(9):4936. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14094936

Chicago/Turabian StyleChen, Hao, Juanjuan Cao, Hongge Zhu, and Yufang Wang. 2022. "Understanding Household Vulnerability and Relative Poverty in Forestry Transition: A Study on Forestry-Worker Families in China’s Greater Khingan Mountains State-Owned Forest Region" Sustainability 14, no. 9: 4936. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14094936

APA StyleChen, H., Cao, J., Zhu, H., & Wang, Y. (2022). Understanding Household Vulnerability and Relative Poverty in Forestry Transition: A Study on Forestry-Worker Families in China’s Greater Khingan Mountains State-Owned Forest Region. Sustainability, 14(9), 4936. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14094936