Abstract

In Macao, the government established the Cultural and Creative Industry Promotion Office and Cultural Industries Committee in 2010, which nominated eight to-be-developed cultural and creative industries (CCIs): design, visual arts, performing arts, clothing, pop music, film and video, animation, and publishing. However, because each CCI has its unique pattern and environmental resources are very limited in Macao, an industrial chain analysis for these eight industries should be conducted prior to policy implementation. Therefore, this study organized an industrial feasibility analysis for these eight CCIs. The methodologies included in-depth interviews, a literature analysis, and knowledge-discovery in databases. On the other hand, this study adopted the concept of creative industries, “the relationship between production and reproduction”, and “the three-circle hypothetical interactive consumption” model for positioning these eight CCIs to choose existing industries in Macao, such as the exhibition, gambling, and cultural tourism industries, that are likely to promote CCIs. Next, the orientations of these CCIs are determined. Finally, it is suggested that the performing arts, design, and visual arts industries should be prioritized currently, and the heritage management and digital media industries are advised as to-be-developed ones. In contrast, the clothing, pop music, film and video, animation, and publishing industries are not so beneficial for Macao’s development.

1. Introduction

Macao has surpassed Las Vegas to become the world’s number one casino city [1]. As it is a special administrative region under mainland China, the trademark of Macao’s unique impression of gambling entertainment has attracted tremendous interest from the Chinese civilians and the government, which has made the authority pay attention to the positive image of the city [2], and it is proposed that cultural and creative industries (CCIs), such as design, visual arts, performing arts, clothing, pop music, film and video, animation, and publishing industries, are important measures that can be utilized to reverse the long-term gambling impression of Macao [3,4]. Consequently, the Cultural and Creative Industry Promotion Office and Cultural Industries Committee in Macao were established in 2010, which are expected to reduce the gambling image by integrating these eight CCIs with existing local advantages, and this is capable of further directing the city to develop diversified sustainable development [4]. In other words, the development of CCIs helps to vary the economic ecology of Macao, rendering the long-term sustainable development of the city. At the moment, Macao is suggested not to focus too much on the gambling industry, which could lead to the monotony of the city. The reason behind the CCIs selection is to provide a means of diversifying development in Macao because CCIs are rooted in all aspects of people’s life. In general, a city develops CCIs more or less, but each of its development maturity and suitability varies. Therefore, this paper clarifies which CCIs are suitable for Macao city to be developed preferentially. However, each CCI has its unique development pattern (requiring different resources), and as there are very limited resources in Macao (such as land), an industrial chain analysis is in urgent need of practice before any action is taken [5]. As a result, key CCIs must be clarified, and those that are suitable for Macao should be determined. Next, the project plans of Macao CCIs are recommended to be established with careful deliberations; for example, the value chain of CCIs is advised to be examined to avoid unfocused, inefficient development models that result in wasting limited resources.

When assessing whether CCIs can be developed and put into practice in a city, it is necessary to first determine whether a city is equipped with adequate production resources and market demand [6]. This research focuses on evaluating the eight potential to-be-developed CCIs nominated by the Cultural and Creative Industry Promotion Office and Cultural Industries Committee in Macao. CCIs are becoming increasingly significant, but theories on how a city’s sustainability can be strengthened through CCI development are not sufficient, especially for traditional gambling cities. To better understand how CCIs connect with the existing strengths of Macao and promote urban transformation and sustainable development, a series of works was carried out in this research.

This research is sectioned into four parts. The first part is constituted by a literature review, sorting out past literature achievements, actual progress for “CCIs” and “the relationship between CCIs and cities”, sustainable development and the theoretical framework of the study. Then, the deficiencies of previous studies are summarized, and we proposed works to be done in this investigation. The second part covers the research methodology, which theoretical frameworks are based on the relationship between production and reproduction and the three-circle hypothetical interactive consumption model to classify the eight types of CCIs according to their suitability for Macao’s development, and introduces the research process, research materials, and research results of this study in detail. The third part contains the research results and discussion. According to the two theoretical frameworks from part two, the data are weighted, and relevant practitioners and scholars are consulted to determine if certain CCIs meet the needs of development and will be of great suitability for Macao. Finally, the data and findings are analyzed and discussed, and the prospective development logic of CCIs for Macao is recommended.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Cultural and Creative Industries (CCIs)

The origin of CCIs can be traced back to the Franks in Germany. Later, the term “culture industry” was used in a work from 1947, Dialectic of Enlightenment, by Theodor W. Adorno and Max Horkheimer. The term, however, at that time referred to as a cultural industry described a concept that is far from the current concept of CCIs today. At the time, Adorno and Horkheimer criticized the so-called culture industry for mass production, mass consumption, and design inspiration, which is based not on the independence of the creator or a certain spiritual meaning, but the logic of the capitalist economy [7]. In the 1980s, sociologists, represented by Bernard Miège, began to review Adorno and other scholars’ views on “cultural industry,” and began to replace “cultural industry” with “cultural industries.” Bernard Miège believed that the term cultural industries can show that the capitalization of cultural production has complex production patterns and diversified operation logic. Although he also thought that the introduction of industrialization and new technology in the process of cultural production would lead to the commercialization of culture, it would also bring new creation and development direction to culture instead of producing the phenomenon of cultural delay as Adorno and other scholars have described. Hence, what Miège and other scholars named “cultural industries” is similar to the modern concept of CCIs [8].

Many international organizations have also been paying attention to the influence of CCIs, and have defined them from different perspectives. The United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) first named “culture industries” and defined these as “content combining creation, production and commercialization”, whose essence is intangible assets with the concept of culture, which is protected by intellectual property rights and presented in the form of products or services [9]. In 2013, UNESCO recognized that the market for cultural industries had changed dramatically due to technological developments. Consequently, CCIs have replaced the singular cultural industry. CCIs refer to “organizations whose main objectives are to produce, reproduce, promote, market, and distribute goods, services, and activities derived from culture, art, and historical heritage [10]”. Numerous papers had adopted the definition of the United Kingdom Department for Digital, Culture, Media and Sport’s (DCMS) for creative industries as “those industries which have their origin in individual creativity, skill, and talent and which have a potential for wealth and job creation through the generation and exploitation of intellectual property [11]”. The World Intellectual Property Organization of the United States, meanwhile, considered the diverse nature of the creative industries, which covered a wide range of different kinds of activity, such as creativity and intellectual activity [12].

The development of CCIs is of academic significance, and most studies of CCIs focused on the following aspects. First of all, studies that emphasized the innovation capacity of CCIs, which area of research analyzes the role of CCIs in affecting the performance of an economy’s innovation [13,14], active innovation [15,16], product innovation [17,18], firm innovation [19,20], and industrial innovation [13]. Second, the management of CCIs has also been receiving attention in academia. A debate has been positioned on whether cultural and creative industrial management “differs” from other forms of management. For many, because of the nature of their products, CCIs raise different types of managing and organizing challenges; it is because managing CCIs creative content is different from that of manufacturing products, requiring more flexibility, and the outsourcing characteristics of CCIs also create different operating and managing challenges [21,22]. Third, CCIs are considered to be a source of potential benefits of transforming culture into capital for the whole economy, affecting the social and cultural aspects of people’s lives [19]; therefore, many scholars proposed policy studies from a theoretical perspective. Various studies on cultural and creative industrial policies believe the orientation of those industries are an important policy for upgrading the national economy [23,24]. As a result, some research analyzed national and civic cultures, and creative industry policies are common research topics [25,26,27]. Lastly, the challenges of cultural policies are also a research area that has received considerable attention [28,29].

2.2. The Relationship between CCIs and Cities

A large number of studies have investigated the relationship between CCIs and cities, and the results of these studies can be divided into the following areas. First, studies evaluated the development capacity of a city’s CCIs. In the early stages of the development of CCIs, Hall (1999, 2000) indicated that CCIs would become the core activities of urban economic development in the future [30,31]. CCIs are seen by many researchers and policymakers as drivers of economic growth and a source of competitive advantage, which is important for economic survival and growth in a city [32,33,34,35]. Many studies have explored how CCIs could enhance the competitiveness of a city by developing assessment indicators and development strategies based on the creative industry of urban development. These studies mainly investigated CCIs and categorized them according to their content and objectives [36,37]. Concerning the influence of CCIs on urban and local development, several studies have indicated that cultural industries should improve the development of CCIs, set up high-tech platforms, develop promising corporate cultures, construct a sound legal system, enhance social security, and promote competitiveness through innovation, art, and the process of collective learning [38,39,40]. Second, studies focused on policies and strategies for the development of urban CCIs. Some studies have explained the challenges and jeopardies in CCIs within the city’s creative ecosystem [41,42]. Others have proved that creative industries drive both economic and employment growth in cities [36,43,44], and many studies have shown that CCIs can lead to the renewal and upgrade of urban policies and strategies [25,27]. Rosi (2014) presented the UNESCO Creative Cities Network (UCCN) and illustrated the theoretical and practical strategies. On one hand, there was a propensity to use the UCCN membership as a branding tool to attract investors and tourists; on the other hand, the tendency to effectively work jointly with the cities of the network to build a stronger identity [45]. Third, some studies focused on the processes of creation and mobility of CCI talent to better understand how mobility, creativity, and creative cities are connected [46,47]. Clustering is a field that has drawn great attention from academics to study the formation process of CCIs [48,49]. Both domestic and international CCI studies are mainly found on the influence of CCIs on urban and local development, elements for constructing CCI parks, and strategies and suggestions for developing CCI clusters. Fourth, the theory of city integrated with CCIs; Smith and Warfield (2008) argued that CCIs have been used in urban development based on two different approaches: the culture-centric and the econo-centric approaches [50]. Ansell and Gash (2007) considered that one form of governance is collaborative and inclusive if it involves a wide range of public and private actors from different backgrounds and interests with the aim of promoting consistency-oriented decision-making [51]. Based on the above two studies, Andre and Chapain (2013) demonstrated that the culture-centric approach is more exclusive than the econo-centric approach, and tends to lead to restrictive governance arrangements [52].

At present, the research on CCIs in Macao mainly focuses on analyzing the development status and strategic suggestions of CCIs in Macao. In terms of the analysis of the development situation, although the development of CCIs in Macao has certain policy orientation and diversified development advantages, its development presents a special unsaturated status, which is mainly reflected in the relatively lagging development of CCIs, narrow regional space, lack of human resources, and the unexplored/unexpanded commercial room of CCIs [53,54]. Due to the small scale of CCIs in Macao, much relevant research mainly analyzed the current situation from the perspective of the Guangdong-Hong Kong-Macao cluster and then makes development suggestions [55,56,57]. In terms of strategies, the development suggestions for CCIs in Macao mainly include optimizing the government’s CCI policies and measures, strengthening the linkage cooperation and exchange with Hong Kong and Guangdong, balancing the CCI structure, recruiting creative talents, and enhancing social attention [53,58,59]. Macao’s economy mainly depends on the tourism and gambling industries, and the development of CCIs based on the abovementioned industries is conducive to the sustainable development of Macao’s economy [60,61]. Since human resources are the main issues in the development of CCIs in Macao, Cheng (2017) analyzed the problems of creative talents in Macao from the perspective of the 3T theory and proposed corresponding solutions [62]. This study is one of the few to examine CCI issues and strategies in Macao from a theoretical perspective.

2.3. Sustainable Development

The concept of sustainable development has been interpreted from multiple perspectives, the most common definition of which comes from “Our Common Future”, famously from the Brundtland Report by the World Commission on Environment and Development (WCED). It states: “Sustainable development is a development that meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs [63]”. WCED recognized the importance of sustainable development as “development that meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their needs [63]”. Subsequently, in 1997, the UN Development Agenda, based on the Brundtland definition of sustainable development and the Elkington approach (people, planet, and profit), proposed that “Development is a multidimensional undertaking to achieve a higher quality of life for all people. Economic development, social development, and environmental protection are interdependent and mutually reinforcing components of sustainable development [64]”. Others thought that sustainable development involves the use and conservation of natural resources and the direction of technologies and institutions to achieve and sustain human needs for present and future generations [65]. In 2016, the UN General Assembly formally adopted the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, which provides a framework for “peace and prosperity for people and planet now and in the future [66]”. As part of this agreement, all of the UN Member States, through a process involving multiple stakeholders, agreed on Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), which are used to indicate and measure progress towards the key SDGs [67]. According to Brundtland’s report, there are eight key elements of sustainable development, such as changing the quality of economic growth [63]. In 2015, the Goals for Sustainable Development were established, which were included in the United Nations (UN)’s Development Agenda 2030. They contain 17 basic objectives, including sustainable cities and communities [68]. The key to sustainable development lies in the long-term consideration of environmental, social, and economic outcomes [69].

Research on sustainable development provides a basis for formulating social policy recommendations and identifying ways to improve the quality of life and the state of the environment, and Ehnert et al. pointed out it has made the concept of sustainable development part of the global discussion not only in the academic sphere, but also “on a broad political and corporate scale [70]”. They also made a comprehensive analysis of the evolution of the concept of sustainable development in this period, which elucidated how the term, sustainable development, first became completely intertwined with the economy, and how it gradually became intertwined with the ecological, social, and corporate realm [71]. However, researchers in the field still do not have a clear and unified definition [69]. Fechete and Nedelcu said, “for sustainable development, a good measurement process should consider the total performance of the organization [72]”. As Connor and Dovers argued, sustainability is “a series and hierarchy of challenges to integrate [73]”; but a few words seemed to capture the essence of sustainability proposed by Tol: “it is everything to everyone [74]”. It must, therefore, be pointed out that a new and better path has been found for everyone and everything, which has begun to repair all of the damage, and that a new way of life has been created that is sustainable for all [69]. In sustainability studies, it is worth noting that some authors used sustainability and business responsibility interchangeably [75]. Therefore, this study discusses the sustainable development of Macao city from the perspective of CCI commercialization.

2.4. Theory Framework of the Study

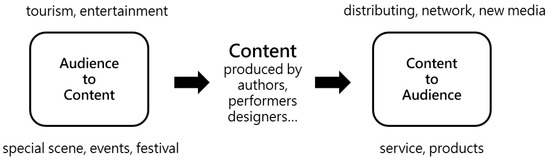

This study will repeatedly quote the framework of “the relationship between production and reproduction” (as shown in Figure 1) as the classifying basis for the eight potential to-be-developed cultural industries. In Figure 1, the center of the figure is the creation and production source of cultural products, including authors, performers, designers, etc. The two extremes of “the relationship between production and reproduction” of creative industries are “content-to-audience” and “audience-to-content”. The representative industries on the right end of the spectrum in Figure 1 include the film, television, music, publishing, and new media industries. In these industries, cultural products are either delivered to shops, stores, and cinemas around consumers’ cultural consumption areas or they can appear on televisions, computers, and handheld video players at home. All of these rely heavily on a steady distribution system established by private enterprises as well as sound intellectual property laws and regulations, which can ensure that those producers can claim rights and profits when consumers purchase and enjoy all of these cultural products. The representative industries on the left end of the spectrum are the performing arts, cultural tourism, and visual exhibition industries. The consumption mode of these three CCIs is that consumers must go to a specific place and at a specific time for an experience, which is different from the experience mode of delivering cultural products to consumers through logistics. In other words, the right end CCIs occur when consumers travel to the destination of creation for consumption. The development of these “audience-to-content” industries differs from that on the right-hand side. These industries do not require industrial chains or massive distribution systems to develop; instead, they rely on a large number of floating populations and tourists [76]. According to data from the Statistics and Census Service of Macao, a total of 39,405,758 people visited the city in 2019, but only half of these visitors stayed overnight [77]. This phenomenon indicates that Macao has the potential floating population to develop “audience-to-content” CCIs, and by enriching or popularizing these categories of industries and providing more entertainment options, it is believed that tourists would be attracted and would be willing to stay more days in Macao.

Figure 1.

“The relationship between production and reproduction” of CCIs [76].

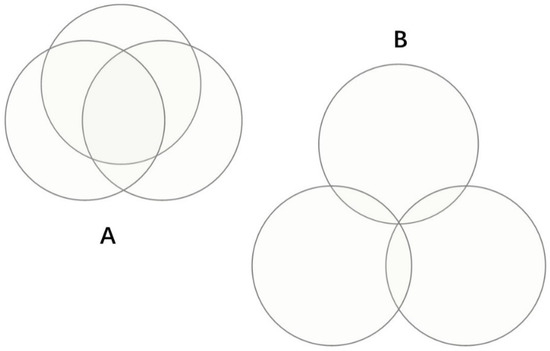

To discuss Macao’s situation, we can borrow the three-circle hypothetical interactive consumption model proposed by Richard Prentice in urban marketing research, which he explored using the Edinburgh Fringe Festival as a case study [78]. Prentice put into this hypothetical interaction the three categories of “tourist historic cities”, “Scottish performing arts in a Scottish context”, and” international performing arts”, which described the three types of tourists who spend most of their money in Scotland. In the hypothetical interaction model, the circles are not fixed but move inward or outward depending on whether the consumption patterns of tourists overlap. If the three circles are close to each other until they almost overlap, this means that the consumption blocks of tourists are highly overlapped. In other words, when a tourist comes to Scotland, he or she will not only visit the ancient cities of Scotland, but also enjoy the Edinburgh Fringe Festival. Visitors to Edinburgh’s world-famous Fringe festival will also see the sights of Edinburgh. In Figure 2, picture A shows that a highly overlapping interaction is ideal, which shows that while there is a primary purpose for a trip, visitors do not spend exclusively on one type of consumption, but on a variety of things within the city that benefit many industrial sectors at the same time. Contrary to this ideal situation, picture B assumes that the three circles in the interaction are dispersed outwards with minimal or no intersection. Such interaction is not ideal because the consumption blocks of tourists do not overlap, which means they do not visit other places for consumption other than their intended purpose. Such a situation also means that the industries in these blocks cannot promote each other’s growth, and in the process of publicity, due to their different consumer groups, they must pay more costs, making it also difficult to develop new customer markets.

Figure 2.

The three-circle hypothetical interactive consumption model [78].

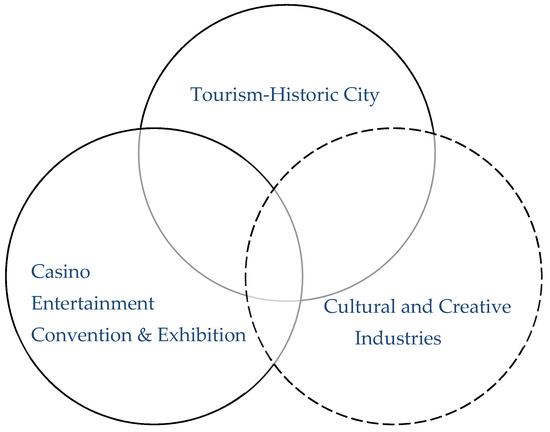

Prentice’s hypothetical interaction model in his Edinburgh Fringe study can be applied to the current gambling and tourism industries in Macao, drawing the two industries into two circles of the three-circle chart, which also shows that the current three-circle chart of Macao is incomplete, and the missing circle is the invisible and unexplored cultural and creative industry. “The three-circle hypothetical interactive consumption” model is suitable for this study because Edinburgh and Macao are both tourist cities with large population flows. In addition, both have cultural and historical heritages that attract tourists. Due to the commonality of the above analysis, the model used in Edinburgh can also be used in the analysis of Macao to a certain extent. Moreover, the theoretical model fully excavates the existing industrial advantages of a city, which is also one of the purposes of this study. According to surveys, most tourists come to Macao to spend money in the gambling industry, and the cluster formed around this industry is relatively strong and complete. When compared with the second tourism cluster, it is also much stronger. If we want to make Macao’s consumer market perfect, we must find the missing link. The CCIs discussed in the present study are the unformed areas in the three circles of Macao.

2.5. Summary

The shortcomings of past studies can be summarized as follows: first, the focus has been placed more on the area of “direct policies and strategies”. For example, researchers have proposed overall conceptual policies and strategies, investigated how CCIs improve urban competitiveness, developed relevant assessment indices, and formulated policies for developing CCIs directly. Such studies did not fully demonstrate the applications and connection of the “original advantageous industries” in a city, but directly focused on the aspect of “policies and strategy issues”. Second, there has been less attention paid to the construction of cooperation between CCIs and the “original advantageous industries in a city”. The demonstration of “CCIs in a city” is directly related to actual operation results; hence, most of the results are reflected in the specific growth of economic indices, and theoretical research has paid little attention to this aspect. Cooperation between CCIs and the “original advantageous industries in a city” could effectively enable a city to have a clear understanding of the effects of the current cooperation and accumulate valuable experience for the future sustainability of a city. However, there is no abundant research in this area. Third, despite being a new field of scientific research, it is already being explored by several institutions, such as UNESCO or the European Commission. The major problem, however, is the fact that the sustainable development of a city is not conceptually discussed in CCIs research. Overall, previous studies lacked a summary of the “connection” of cooperation between the two parties, as well as an understanding of the degree of importance of various factors of cooperation between CCIs and the “original advantageous industries in a city”, and they regarded CCIs as an important means of sustainable urban development. Fourth, although there is a lot of research about the strategy for the development of Macao’s CCIs, most of them lack theoretical framework support. Therefore, this paper puts forward the logic of the sustainable development of Macao’s cultural industry with the help of these two theories. This study takes into account “the relationship between production and reproduction” and “the three-circle hypothetical interactive consumption” model as the theoretical framework for positioning and conducts an industrial chain analysis for the eight potential to-be-developed cultural industries in Macao. The research methods applied included in-depth interviews, literature analysis, and knowledge-discovery in databases from the Government of Macao Special Administrative Region Statistics and Census Service [79]. Afterward, Macao’s CCIs were further divided into industries to-be-developed, industries without expansibility, and industries that needed to be added. The conclusions drawn in this study are of great significance in clarifying the connection between CCIs and the “original advantageous industries in a city”. Further, the study results could serve as a reference for promoting the sustainable development of casino cities, such as Macao.

3. Methodology

In this study, the empirical analysis of CCIs in Macao relied on in-depth interviews, in-depth text analysis, and case studies. We chose Macao as a typical case for this study owing to the strong representation of its image of transformation as a casino city with the help of CCIs that enable the city to have diversified and sustainable development [3]. On the other hand, some of Macao’s CCIs are also an important part of China’s industrial revolution, with a high reputation in Southeast Asia [80].

With these approaches, and in view of the characteristics of the different actors involved, the corresponding text sources for this study were chosen. The main texts studied were sourced from newspapers and journals, with data selected from the local government’s official websites. We studied 30 relevant policies, documents, and proposals publicly issued by Macao [81]. We searched for discussions on the development of CCIs in these documents to examine how the Macao government has positioned and reimagined the city, as looking into these documents was considered an important part of the research methodology. We also collected data on cultural and creative industrial development using the websites of major enterprises and identified how enterprises and nongovernmental organizations promoted development.

When assessing whether a CCI can be developed and put into practice in a city, it is necessary to determine whether the city is equipped with adequate production resources and market demand. Current research has focused on evaluating the eight potential to-be-developed cultural industries nominated by the Cultural Creative Industry Promotion Office and Cultural Industries Committee in Macao. The analysis tools used in this study include interviewing practitioners, government managers, and scholars working or researching in the eight CCIs, and analyzing knowledge-discovery in databases provided by the Macao Government Statistic Office [82,83] to determine if certain nominated cultural industries meet the needs of development and would be of great interest to Macao. In other words, the analysis framework of this study was based on taking into account the practitioners of CCIs, including governmental personnel, company owners, artists, designers, and so on. Hence, we interviewed the above people through field research. We visited the study locations three times from February 2019 to September 2021. A total of 20 key interviewees were interviewed using semi-structured interviews that each lasted 15–40 min. The contents of the in-depth interview are mainly 5–10 questions about the development status of the CCIs in Macao.

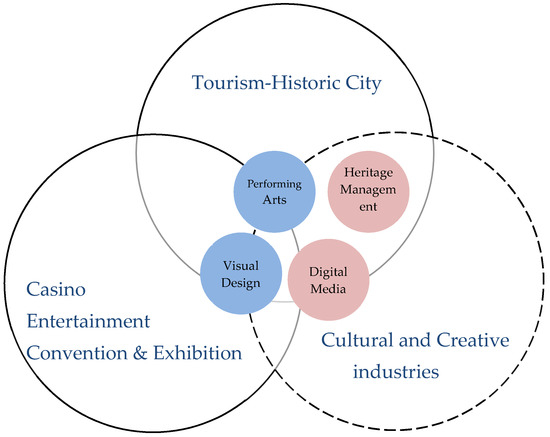

In this study, “The relationship between production and reproduction” and “The three-circle interactive consumption” were chosen. The reasons for choosing “Model” as the theoretical framework of the study are as follows. “The relationship between production and reproduction” applies to this study because it classifies CCIs into two categories based on the consumption mode of cultural products. Such a classification is helpful for this study to preliminarily consider what types of CCIs can be developed in Macao as a city with a large population flow. Macao’s original advantageous industries, such as casinos, tourism, conventions, and exhibition, can quickly exclude the types of CCIs that are not suitable for development. Moreover, “The three-circle interactive consumption” model is suitable for this study because Edinburgh and Macao are both tourist cities with large population flow. Casinos, conventions, and exhibitions, each segment is forming an important element of one of the three circles in Macao. In addition, both cities have a cultural and historical heritage that drives tourists to visit, which forms the second round of the three circles of Macao. As per the above mentioned, the model adopted by Edinburgh can also be used to analyze Macao to some extent (Figure 3). Besides, the theoretical model fully excavates the existing industrial advantages of a city, which is also one of the purposes of this study.

Figure 3.

The application of the three-circle interactive consumption model in Macao.

4. Feasibility Analysis of Macao’s CCI Development

Before assessing the sustainable development of Macao’s CCIs, the eight to-be-developed CCIs in Macao must be individually analyzed to understand their development feasibility in Macao, and the development of CCIs should be classified according to the urban characteristics of Macao. Therefore, in this section, this study analyzes the eight to-be-developed CCIs in Macao to clarify the possibility of the development of the eight CCIs in Macao according to their characteristics.

4.1. Design and Visual Arts Industries

The design and visual arts industries include art forms, such as ceramics, drawing, painting, sculpture, printmaking, design, crafts, and architecture, which can be divided into two models of the industries. One model is called B2B (business-to-business), which mainly encompasses the provision of design services, such as designing advertisements for commercial products, interior design, and decorating business offices. The other model is B2C (business-to-customer), which involves product design. According to research on the cultural industry in the United Kingdom, the traditional definition of workers in the field of visual arts is that such individuals make a living by selling their creations (their finished products). However, nowadays, workers in the field of design and visual arts have 25% of their main income sourced from selling their creations, while the rest of their earnings comes from B2C services [76]. In other words, the majority of revenue in the design and visual arts industries comes from B2B services. With the booming development of the gambling, exhibition, and tourism industries in Macao, the visual arts industry has been enhancing the value and competitiveness of those industries, while these industries bring steady upcoming B2B customers for the design and visual arts industries. For example, 1536 exhibition events were held in Macao in 2019 (as the data of exhibition numbers in 2020 and 2021 are affected by COVID-19, the data in 2019 is used as research evidence) [82], which demanded huge support from the visual arts industry. The gambling industry spent MOP 3880 million (about USD 484 million) on marketing and promotion, and MOP 1540 million (about USD 192 million) on building renovations in 2019 [83]. Another example, the cost of the exhibition hall production and site layout accounted for 37.4% and 35.4% of the total annual expenditure in the past two years, respectively [82]. It shows that the existing conference industry in Macao spends more than one-third of its expenditure on the design and visual arts industries. It demonstrates the demand of the conference industry for design and visual arts industries, and the ability of the exhibition industry to drive the development of design and visual arts industries. Hence, there is a strong interconnection between the design and visual arts industries and existing industries in Macao, such as the gambling, exhibition, and tourism industries.

The design and visual arts industries can be seen by people in their daily lives; hence, these industries serve as key factors in impressing the core value of a product in consumers’ minds. Whether Macao develops cultural industries or any other types of industries or enterprises, the design and visual arts industries are important components in enhancing enterprises’ innovating ability and competitiveness. According to the Statistics and Census Service of Macao, the design and visual arts industries contributed MOP 2473.9 million (about USD 307 million) in output service value in 2019, which is MOP 373.6 million (about USD 46 million) higher than the previous year [84]. This data further confirms the economic contribution of the design and visual arts industries in Macao. In addition, these industries can function through means such as beautifying the city’s appearance and glorifying the image of the city, which can serve as the driving force for cultural tourism and increase revisit intention [85,86]. Although Macao is a cultural tourism destination, there is still room for improvement in the design and visual arts industries, which also reflects the importance of these industries to Macao. At present, the development of these industries has not matured completely yet, so future efforts and support are still needed [87]. Post-visiting, which refers to the end of the journey or after the journey, is also an important traveling phase that affects tourists’ impressions of a journey [88]. In this phase, souvenirs are key elements for tourists to retain their memories. However, as a famous tourist destination, the gift shops in Macao all around are insufficient and immature, and the design and visual arts industries can come in and assist with souvenir design and production. The development status of the design and visual arts industries is becoming a key factor in promoting a cultural city image in Macao.

4.2. Performing Arts Industry

The performing arts include forms of creative activity being performed in front of an audience, such as drama, music, and dance. Among all CCIs, “live shows” are the most audience-driven. This also means that the performing arts industry belongs to CCIs of the “audio-to-content” type. Macao has diversified types of lodging and sufficient accommodation to cope with many visitors. According to the Statistics and Census Service of Macao, the number of arrivals to Macao increased from 30,714,628 in 2015 to 39,406,181 in 2019 [89], and the number of hotels increased from 99 in 2014 to 124 in 2020 [90]. The two high-level casino resorts in Macao, The Venetian Macao and The City of Dreams, can provide appropriate spaces and facilities for performing groups. For example, the Venetian Macao is equipped with the Golden Light Museum as a multi-functional indoor performance venue and the Venetian Theatre [91]. For another example, The City of Dreams is accompanied by the stunning “House of Dancing Water”, which features approximately 2000 seats and is designed and organized by the world-renowned Sandi Pei of Pei Partnership for 5 years, worth more than HKD 2 billion (about USD 25 million) [92]. In addition, these gambling industries have transformed their businesses into a broader realm of gaming entertainment by combining their businesses with performing arts, an example of which is the water show called the “House of Dancing Water”. According to The Statistical Yearbook 2019 (as the data of exhibition numbers in 2020 and 2021 are affected by COVID-19, the data in 2019 are used as current research evidence) from the Macao Statistics and Census Service, the performing arts industry has generated MOP 1441 million (about USD 180 million) [93]. Furthermore, according to The Cultural Industrial Statistical Yearbook 2019, in the “cultural exhibition” sector, which focuses on performing arts production, the number of operating establishments increased by 21 to 193 and the number of staff increased by 15.4% to 2291. Annual service revenue amounted to MOP 1.22 billion (about USD 151 million), accounting for 84.6% of the segment, an increase of 2.2%. Large organizations increased the operating expenses for publicity and promotion, performance and exhibition production, totaling MOP 160 million (about USD 19 million) in 2019. A total of 76 performing arts training organizations were operating; an increase of five over the previous year. Their staff increased by 7.3% to 630. Total fixed capital formation increased 24.1% to MOP 4.3 million (about USD 533 thousand) [93]. These data show the potential of the performing arts industry in Macao. The abovementioned advantages have set up a solid foundation for Macao to develop the performing arts industry [94]. If Macao could further magnify and extend its advantages in gambling entertainment, then more visitors would be attracted, which would enrich and stimulate the performing arts industry in Macao and endow the gambling industry with entertainment elements of more cultural depths. According to data from the Statistics and Census Service, a total of 39,405,758 people visited the city in 2019, but only half of these visitors stayed overnight. If Macao can develop the performing arts to improve the entertainment options in the city, it could increase the length of stay of visitors to Macao [95].

In addition, the main characteristics of the performing arts are to foster talents with a high degree of penetration in CCIs, such as playwrights, stage designers, stage performers, and costume designers; related techniques and technologies, for instance, from basic lighting design to high-end stage display technology, will benefit the development of this industry. Moreover, as these talents become more experienced and sophisticated, they can not only improve the quality of the performing arts industry in Macao, but also be involved in other related cultural industries, such as design, clothing, and even the film industry. On the other hand, this industry can offer job opportunities locally for graduates from design and culture-related majors. In terms of talents and technologies, the advancement of the performing arts industry would have a positive effect on Macao’s overall CCIs.

4.3. Clothing Industry

Should the clothing industry be developed successfully, the industry would be able to support numerous finished product outputs continuously. Land and human resources are the fundamentals for the development of the clothing industry. Although Macao’s clothing industry had flourished in the past, because of the advantages of the above two resources in Mainland China, Macao’s clothing factories have gradually moved to the mainland. Macao currently relies on the tourism industry as its core value for economic development, which is not suitable for conducting too much land development as it leads to pollution of the land and natural resources because the clothing industry is also based on the consumption of land and the environment.

Macao’s land covers 32.9 square kilometers, and, compared with Mainland China’s vast hinterlands, Macao is no longer suitable for developing the clothing industry. Regarding Macao’s clothing industry, an interview with manager Guan Zhiping from the Macau Productivity and Technology Transfer Center was conducted, and he claimed,

Macao has no official top-end fashion training school for potential talents in the field of the clothing industry, and the small population makes it such that there is a shortage of techniques and talent. At present, only the Macao Productivity and Technology Transfer Center offer related professional training. The program lasts 18 months, and a certificate is issued upon completion. Every year, approximately 15 to 20 students graduate from the center. Due to the good economic development in Macao, designers who engage in clothing design have other jobs on weekdays, so instead of being full-time designers, they only do clothing design on weekends. The clothing markets in Macao are quite small, such as the T-shirt, do-it-yourself, flea, and tailored markets. Macao is still unable to develop large clothing designer brands like Hong Kong. In addition to small design studios, there are also businesses that design and produce uniforms for hotels and festivals, which are not real fashion designs.[96]

In addition to the limited resources mentioned above, if the clothing industry is to be further developed or transformed into a fashion design industry, more professional branding talents and marketing strategies are needed, which are currently greatly lacking in Macao [97]. According to the above discussion, it is concluded that the clothing industry is against the types of cities suitable for Macao’s development, which is for consumers to consume in specific destinations. Therefore, the clothing industry belongs to the “content-to-audience” CCIs, which is not appropriate for the development of Macao.

4.4. Pop Music and Film Industries

The pop music and film industries belong to the “content-to-audience” classification of industries, which requires specialized professionals, sound distribution systems, and mature media networks. However, Macao is still in the early stages of the development of the pop music and film industries, and the above conditions are not yet up to standard. Regarding the pop music industry, live music in pubs or bars is the majority in Macao; however, this cannot be categorized strictly as a pop music industry (it belongs to music activities). In the film industry, Macao has the advantage of owning famous and popular movie scenes, and therefore, many film workers come to the city to shoot. However, only a few films are released by Macao itself in a year. Nevertheless, several new local three-dimensional theater projects have been launched by gaming practitioners who seek to focus on entertainment.

This study targeted data collection toward education units related to the film and video and pop music industries, and only one program related to these two industries (named Film Management and Production) was found at the Macao University of Science and Technology. This implies that there is a shortage of talent training for the pop music and film industries in higher education training. As a result, these talents receive training and experience at large companies specializing in music or film production. Furthermore, funding is also an important factor. The scale of the music and film market and production in Macao is so small that investment is deficient. According to The Statistical Yearbook 2020 published by the Macao Statistics and Census Service, in the film and video market, there were five cinemas in Macao and 76 production and distribution units, with total revenue of about MOP 115 million (about USD 14 million) [98]. Compared with 2011, the number of cinemas decreased by two units. There were seven television and radio broadcasting stations in Macao in 2016 [99]. When comparing the number of cinemas in 2020 with that of 2016, the number dropped by three units. The local media distribution system in Macao is not as large as that in Hong Kong and Taiwan. In addition, some research proposes that the current challenges facing the movie and television industry in Macao are: (1) ignoring the concept of organizational innovation; (2) lacking a talent cultivation system; (3) lacking core knowledge and key personnel [100]; and (4) Macao films still face the structural contradiction of insufficient supply and sometimes oversupply in the local market [101,102].

However, the products of film, video, and music require a massive media distribution system that can effectively and successfully deliver these products to potential consumers. The abovementioned data show that the size of the film market in Macao is obviously small, and it is gradually decreasing. As for the local market demand, live shows occupy the majority, such as live performing arts in hotels, bar singers, and bands. However, in Macao, there are no local talents and planning units in related fields; hence, performing opportunities in the music market would turn to foreign or overseas professionals, such as those from Hong Kong or other places.

4.5. Animation Industry

The animation industry belongs to the “content-to-audience” classification of industries, as its manpower resource requirements demand an exquisite division of workers and highly specialized technology, and the full completion of the work also needs a mature distribution system. In Asia, opportunities for the Asian animation industry have been brought to full play by Hong Kong and Japan, whether in manga or anime. There are also many famous works from Hong Kong, and it has even adapted manga or anime to other forms of cultural productions, such as online games and television series. In recent years, even the nearby city of Guangzhou has developed and strengthened the animation industry. Macao faces a hostile environment lacking in talents and distribution systems. Macao still has a long way to go before developing its small number of animation works into a mature animation industry. Li’s (2012) research proposed that under the current conditions and actual situation in Macao, it is not optimistic about the development of Macao’s animation industry. The reasons come from the following aspects: for example, due to the influence of the real estate industry structure, it is extremely inclined toward the gambling industry, and it is difficult for small and medium-sized enterprises to survive, not to mention the immature animation industry. Macao is lacking a better broadcasting platform and superstar effects for professionals or animators, respectively. Consequently, Macao is not able to establish a unique image or style in the animation field [103]. Other research also asserted that Macao’s animation industry is small in scale and has little influence on surrounding cities [104]. This study interviewed Mr. Cui Deming and Mr. Jin Hui, who have had many years of experience in the toy design industry. The following information is the comprehensive conclusion of the organized interview draft combined with the investigation of this study. The animation industry in Macao is now in its initial stage, and more than half of the workers in the industry are amateur cartoonists having their own small-scale personal studios, but the animation industry requires a highly specialized division of labor and many human resources. In addition to the professionalism that is needed, the required talents have to be experts in the production process of a certain stage. However, talents cultivated locally in Macao can be used only in graphic design, and other animation talents do not have commercial competitiveness. The development of the animation industry in Macao is inadequate in terms of talent and resources [105]. This study also interviewed Xie Kunze, a general manager of the content and image division of China’s first animation company, Aofei Animation Culture Co., Ltd. (Guangzhou, China), and he mentioned,

To improve and optimize the development of the animation industry, animation producers must first have a basic local market that cannot be too small, and they need to understand the needs of the local culture in order to integrate their works with the local culture.[106]

Obviously, due to the insufficient market demand, which is the primary prerequisite for developing Macao’s animation market, and the lack of a professional distribution system [104], it is hard to expand the industry to overseas markets, or even to compete with neighboring cities.

4.6. Publishing Industry

The publishing industry also belongs to the “content-to-audience” classification of industries. Hence, the demand for integrated industry chains and land resources is no less than that of other cultural industries. In addition, the book market in Macao is too small, and most Macao writers tend to write literary works, which results in a relatively narrow reader group [107]. According to the latest statistics from the Macao Central Library, there were 638 books published in Macao in 2020 [108]. In addition, a study pointed out that more than half of the 638 books are government publications, which infers that these publications are of less value in the market mechanism. There were 200 publishers in 2020, but nearly three-quarters belonged to non-profit organizations, and they published fewer than 10 books a year on average, with the majority publishing one to three books. The above data show that the publishing industry in Macao has not formed a large-scale commercial operation. Access to brick-and-mortar bookstores in Macao is limited, and the Pin-To Livros bookstore in Discussion Official Plaza is the only one that is close to consumers. However, because of the noisy surroundings and crowded tourists, the bookstore cannot be easily found. Brick-and-mortar bookstores are the most direct way to allow books to reach consumers. It is evident that in Macao there are problems, such as the shortage of access to bookstores and a lack of commercial publications. The publishing industry of Macao should start with these aspects to improve access to bookstores and cultivate consumers’ reading habits.

4.7. Summary

Based on the above findings, a comprehensive Table 1 was developed containing the characteristics of each major industry, the role of each CCI in local and regional development, and development recommendations.

Table 1.

Development characteristics and suggestions of eight CCIs in Macao.

5. Discussion: Development Logic of CCIs in Macao

This section applies the concept of “the relationship between production and reproduction” and “the three-circle hypothetical interactive consumption” model to analyze the development logic of cultural industries in Macao. The representative “content-to-audience” industries include the clothing, pop music, film, animation, and publishing industries, which rely on a perfect distribution system established by private companies as well as a sound industry chain. Under the restrictions of geographical and human resources, it is not suitable for Macao to develop such industries. In addition, the second category of cultural industries is “audience-to-content”, such as cultural tourism, exhibitions, performing arts, museums, etc. As Macao has a large flow of visitors as well as mature exhibition and hotel equipment, it is a feasible direction and basic logical thinking that CCIs in Macao should be developed.

5.1. Orientations of CCIs in Macao

The performing arts industry belongs to CCIs in the category of “audience-to-content”, according to the “the relationship between production and reproduction” classification concept of the creative industry. In addition, from the perspective of the pure exhibition, the design and visual arts industries also belong to the CCIs in the category of “audience-to-content”. The well-known prosperities of the three major industries, the cultural tourism, gambling, and exhibition industries, are the driving force of an endless stream of tourists for Macao, which should serve as foundations for Macao to develop “audience-to-content” cultural industries, and it also reflects its unique advantages of the cultural industry development in Macao compared with other cities. One of the advantages is that the development of these three major industries has raised the demand for the design and visual arts industries, providing designing services for the major industries. The gambling industry improves the diversified development of the performing arts market under the differentiated entertainment business concept. In addition, endless visitors to Macao sustain stable customer sources for the performing arts, design, and visual arts industries. Therefore, Macao should utilize its own three advantageous industries and their demands for CCIs as auxiliary foundations for developing the performing arts industry as well as the design and visual arts industries. All in all, Macao is recommended to focus the development directions of CCIs on the logic of “audience-to-content”.

As for the clothing, pop music, film, animation, and publishing industries in Macao, the successes of these industries’ development must be equipped with complete industrial chain structures, specialized divisions of labor-consuming huge human resources, and perfect distribution systems. Based on the analyses of eight cultural industries’ development conditions in Macao, the developing conditions and needed resources required for the clothing, pop music, film, animation, and publishing industries are very restricted or the development scales of which are in the initial stages, so the integrity and maturity of the industrial development conditions are insufficient. According to the concept of “production and reproduction”, the clothing, pop music, film, animation, and publishing industries belong to the “content-to-audience” industries. It is not appropriate to develop such industries in cities such as Macao, where resources are restricted in space and manpower. Macao is suggested to supply services of a certain industry link or utilize the exhibition end as the main orientation for the future CCIs planning direction.

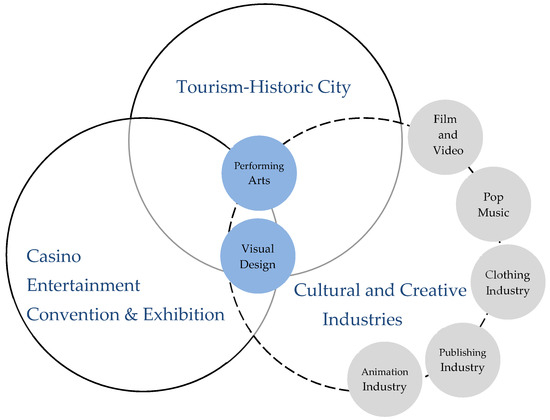

According to the above theoretical analysis results, the relationship between the existing advantageous industries and the eight cultural industries in Macao was plotted by the researchers, as shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Orientation map of CCIs in Macao.

The performing arts industry and the design and visual arts industries belong to the “audience-to-content” CCIs, which are suitable for the development of tourist cities such as Macao. In addition, such CCIs have tight associability with the existing advantageous industries in Macao: the cultural tourism industry, the exhibition industry, and the gambling industry, which are audience-driven industries. Moreover, the talents cultivated by such industries, such as those in the fields of design and performing arts, can also be applied to a wider range of industrial and commercial companies. Therefore, these kinds of CCIs are more likely to be developed in the future. In this way, such CCIs should be the focus of the development categories in Macao in the future.

The clothing, pop music, film, animation, and publishing industries belong to the “content-to-audience” category, whose common characteristics of successful development are being equipped with mature and complete industrial chains from the original chain to the market chain. However, Macao belongs to the “audience-to-content” tourism experience category of cities, where development is limited by geographic space. The immaturity of the mass media communication system leads to a lack of huge distribution systems, making it unable to support “content-to-audience” industries. Moreover, according to the analysis results in this section, it is hard to query the scales and outputs of such industries in the database of the Macao Statistics and Census Service, which reflects the fact that Macao does not have the advantage of any complete industrial chain in the development of such cultural industries or that such industries are in the primary development stage. Coupled with the fact that such industries cannot be combined with the existing industries in Macao, the future planning direction can only take charge of a service character in the original chain or display chain.

5.2. Industries That Need to Be Added

During the surveying process, this study found that, except for the above eight cultural industries as shown in Figure 3, Macao is advised to add the heritage management and digital media industries according to its demand, as these two industries help cultural industries to be more closely linked with the existing industries, promoting their development thoroughly and completely.

5.2.1. Heritage Management

Tourist gaze refers to tourists visiting tourist spot attractions in order to find differences from their daily lives [109]. Macao has rich cultural heritages, including its historic center, which was listed on the UNESCO World Heritage List on 15 July 2005, becoming the thirty-first world heritage site in China. An investigation of Macao’s local tourist resources by Hilary Du Cros shows that Chinese tourists and tourists from abroad rank the Ruins of St. Paul as the first tourist spot to visit in the city, but the pastiche-style cultural theme park Fisherman’s Wharf is their last choice, which reveals that tourists value the authenticity of cultural spots [110]. For many historic cities, it is easy to include cultural heritage characteristics into cities, with tourism as the main direction. The key reason lies in the nature of the heritage site itself, which makes tourists feel as if they are at different tourist attractions at different times. This is caused by the demand for high-quality management of the heritage itself. The marketing of a place depends on the qualities of vibrancy or vitality, while the prominence of cities as cultural hubs follows patterns of cultural consumption in cultural tourism and the attraction of aspirant arts professionals as producers and consumers of a city’s image [111]. The book The Tourist City mentions that tourists use all kinds of senses to perceive a place; hence, tourist attractions should avoid any negative messages to create a positive image [112]. However, taking the Ruins of St. Paul as an example, which is the most famous cultural heritage site in Macao, it is close to people’s residences, and the residential clothing and cultural heritage are in the same space, which indeed reduces the sanctity of the tourists’ experience in connection with the heritage site. In addition to the halo of a world heritage site, maintaining its value in tourists’ minds has become an issue for Macao; thus, heritage management has become a necessary unit to be set up in Macao.

Despite criticism for its heritage policies, Macao has done a better job of conserving its built environment than many of its neighboring territories that have experienced rapid urban development in recent decades. Heritage conservation in Macao was introduced relatively early. It can be traced back to the 1950s when the government created a registered list of the city’s architectural monuments considered important to represent the Portuguese state [110,113,114]. By the 1970s, accelerating redevelopment led to the enactment of new legislation to protect the city’s historic precincts, which included the Avenida Almeida Ribeiro, an important old commercial district. In 1982, the government founded the Instituto Cultural of Macao to take charge of implementing cultural and heritage policies [115]. In 1987, the government implemented new planning strategies intending to preserve the city’s historic precincts while addressing the need for urban expansion. This resulted in several major reclamation schemes located away from the old city center. Along with other newly launched infrastructure and building projects, fueled by speculative investments in this period, they would also mark the beginning of a new phase of radical transformation of the city [115]. The Cultural Heritage Department was established by the Portuguese administration in 1976 under the supervision of the Instituto Cultural of Macao [110,115]. The primary task of the department is to classify and conserve Macao’s built heritage, particularly its large stock of colonial-era architecture and monuments. Although the government has long prided itself on doing a good job of protecting its historical buildings, no system had been set in place to provide proper training for local conservation professionals until the end of the colonial period [113].

For the maintenance and management of cultural heritage, it is advised to carry out further overall planning and management of the surrounding environment rather than only completely repairing buildings in historic urban areas in a passive way. Starting from circulation management, it would be appropriate to guide tourists in Macao to visit other sites with historical and cultural characteristics and create a new beautification design for the historical site through circulation planning, which could additionally ease the usual overcrowded visitors from the Ruins of St. Paul. Such planning can not only optimize the integral city image of Macao, but also provide employment for the local design industry. In addition, the surrounding environmental planning of historic sites is one of the key objectives advised to be established by heritage management, such as selecting conditions and categories of surrounding business presences and setting up souvenir shops in the sightseeing circulation planning at the appropriate time. In other words, through integral heritage site planning, another “tourism bubble” is likely to be created to attract visitors. Specific and famous mixed-purpose street blocks, gathering a high concentration of cultural sites, serve as a focal point for tourist attractions [115]. For example, Dublin’s Temple Bar in Ireland has been reborn from the crisis of the old city under the concept of building cultural quarters [116]. The planning of the Temple Bar cultural quarter is suggested to be referred to by Macao heritage management.

Although the local CCIs in Macao are still in their incubation stages, they are equipped with active cultural community activities [117]. Another objective of heritage management units organized and executed by the public or government sector is to create a complete combination of local cultural community activity and cultural heritage. Under such planning, the tourism value of cultural activity in enriching the heritage area lies in the probability of visitors returning and visiting again. By leasing idle buildings for cultural activities, the government can, for example, convert the idle space into a small-scale theater or rehearsal hall as well as exhibition and performance venues for diversified performance and exhibition places in Macao. In addition, site management personnel can also be provided to maintain the sustainability of the exhibition and performance venues, even beautify the environment, and further develop them into tourist attractions to solve the congestion problem in the major tourist sites in Macao. In an interview with our research team, the Cultural Bureau referred to the same concept:

The planning focus of the Cultural Property Office is on the activation of the old district, which means developing several nodes in the tourist attraction into exhibition and sale places, or inserting key demand spaces into the adjacent area of urban space on the basis of cultural community activities. For example, the Cultural Bureau can insert the leased rehearsal hall into the area targeting the performing arts. Through the polycentric activation of the old district, cultural activities in such places can also be ensured not to be divorced from public life or tourist routes. Shifting from the conservation aspect to the activation aspect, these node spaces in the city can be optimized, the local cultural environment in Macao can be gradually improved from each point, and the line can be expected to be connected under long-term planning, which may even become a plane for the production and consumption of cultural activities.[4]

For Macao, whose development of CCIs is in its initial stage, it is appropriate to make timely use of its basic tourism resources and to make a comprehensive, integrated plan for CCIs and cultural tourism. Huddersfield is a good example of how a smaller town or city’s culture has contributed to the regeneration of the town and the wider local authority district [118]. Italy also uses the concept of cultural districts, which combine with its local legacy of history and art, while the planning of the districts emphasizes the protection of cultural heritage and its new value orientation [119]. Macao, a cultural tourist city, can refer to the planning of cultural districts in Italy to manage its heritage.

5.2.2. Digital Media

Even though local digital media in Macao is still in its infancy, there is still a need to add this industry to the list of industries to be developed. Digital media has a wide range of diversified functions, such as entertainment application, education promotion, business purposes, and information sharing, which are necessary basic industries and projects for the development of a city. In the classification of creative industries, the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD) also includes digital media as one type of project. Hence, the digital media industry is bound to complement other industries to be integrated with the world if a city intends to develop its cultural industry instead of acting blindly. The digital media industry can also be divided into two modes, which are the same as those of the design industry. The first mode is referred to as B2B (business-to-business), which mainly includes the provision of services, such as providing web erection services for other manufacturers or merchants; the other mode is referred to as B2C (business-to-customer), which mainly includes the selling of digital media products to customers. With the vigorous development of the gambling, tourism, and exhibition industries, it is an undeniable fact that Macao has a demand for digital media in the B2B mode. However, there is still room for improvement since Macao is still in the infant stage of development in this aspect. In addition, the perfect development of the digital media industry can improve the tourism industry or general industrial and commercial companies in the city. Moreover, it is inevitable that digital media will be combined with the design industry for further development. Therefore, the development of the digital media industry can also drive the design industry and provide the channels for local cultural products in Macao to be sold outside.

Under the restrictions of space, digital media serves as the main channel for approaching the city, which is also the primary way for foreign people to get to know a city and the main ways to establish a first impression of the city. With the tourism industry as the leading industry in Macao, digital media has become an industry-related project that should not be neglected. Before sightseeing, tourists must learn about the city through relevant official tourism websites. At this moment, digital media becomes the spokesperson of the city, which plays a critical role in deciding whether the city can be promoted outside, whether the city may become the first choice of tourists, and whether the city may leave a good impression. The appeal of modern tourism is concentrated on experience [120]. However, during the research period, the researchers queried the relevant websites of government units in Macao several times and found that the website design and planning in Macao were not humanized; further, it is not easy for people to obtain data. From the fundamental websites to the public interaction multimedia set-ups in tourist attractions, these provide inadequate information on aspects such as public transport and tourist attractions. In particular, the survey experiences of the research team’s visits to the attractions of Macao several times reflect the fact that Macao has not set up a facility for tourist interaction in tourist attractions, not to mention multimedia interactive projects. As a result, Macao should actively combine the tourism industry and digital media effectively. At present, Macao should start by re-planning its tourism website and further setting up interactive multimedia projects in tourist attractions. Such a combination can effectively improve the degree of convenience for tourists to query data and the attractiveness of tourist spots, which may correspondingly raise tourism willingness.

The analytical findings in connection with the abovementioned cultural industrial chain shows that the main restrictions for developing CCIs in Macao could be the narrow development of local markets, small manufacturing spaces, immature distribution systems, and other problems. Several interviewees in this study also put forward the importance and demand of digital media. Since digital media has cross-border influence and the capability to make up for the lack of development of CCIs in Macao, original works in Macao can be published to overcome the market and space barriers. Moreover, digital media also has a direct impact on various stages of the industrial chain itself. In the original stage, it can increase the work efficiency and output quality of industrial workers and can even provide amateur workers with simpler application media tools to improve the output quality; in the manufacturing stage, it can improve the production and communication efficiency between various units; in the marketing stage, it can expand the marketing field through the diversified applications of cross-media; and in the market (display) stage, it can overcome the market and space barriers, and can increase the number of consumers. Moreover, digital media can even push the optimization and diversification of various current cultural activities in Macao.

Although the economic performance brought about by the development of digital media cannot be measured in a short time, it is still worth focusing on the operation of such a project in Macao when considering long-term plans and its extra advantages in various industries. At present, the application of digital media in Macao presents a relatively low-quality state. The Macao government should invest more funds and staff into the positive development of the digital media industry. Starting from the establishment of relevant departments on digital media systems, it would be appropriate to cultivate digital media talents and put talent into various industries in Macao to help it rapidly enter the electronic era, which will serve as the basis for the cultural industry development in Macao. In addition, it is necessary to improve the website system of Macao tourism to be more user-friendly and to add interactive digital multimedia at hot attractions in order to increase the interest in the attraction and prolong the stopping time at a single tourist attraction. Most importantly, it is encouraged to assist various industrial and commercial companies to improve their maturity levels in using digital media, which will contribute to operational efficiency and network publicity for industrial and commercial enterprises in the whole city.

5.3. Connection Benefits of Cultural Industries and Existing Industries in Macao

As shown in Figure 5, the digital media, performing arts, and design and visual arts industries are closely linked with the casino, exhibition, and tourism industries that have been developed to be quite mature and have been advantageous in Macao. The digital media, performing arts, and design and visual arts industries also provide value-added services for the above three existing advantageous industries. This study only discusses the connection benefits between these cultural industries and the existing advantageous industries in Macao in general.

Figure 5.

Development concept map of cultural industry in Macao.

The exhibition industry in Macao requires the design and visual arts industries to provide beautifying, value-added services, such as exhibition decoration and advertising poster output. Interior design can provide the exhibition venue layout and plan. Visual arts and design can provide advertising media, such as posters, brochures, and flyers. In addition, digital media can not only provide marketing and advertising on the internet for the exhibition industry, but also provide diversified media interactive services during the exhibition period. The performing arts can also enrich the content of the exhibition industry. The performing arts industry can be interspersed in exhibitions as entertainment programs, providing participants with entertainment options besides official duties, and improving the utilization of advanced equipment in exhibition halls.

The gambling industry in Macao is now gradually developing toward a broad gambling entertainment industry. In addition, the performing arts are also an important industry for the entertainment development of the gambling industry, and the staff cultivated by the performing arts can also be engaged in other relevant CCIs. Digital media, design, and visual arts are basic demands for the high-quality development of all industrial and commercial companies, and the gambling industry is no exception in terms of talent and industries in these areas. Design and visual arts provide beautifying functions, which supply services relating to interior and advertising design for the gambling industry. In addition, the digital media industry can improve the efficiency of commercial operations in the gambling industry. For example, the digital media industry can improve online booking and social media marketing systems for the gambling and tourism industries. The gambling industry can also expand its online business through the digital media industry. Moreover, although posited as a resistant force against ‘casino capitalism,’ some heritage projects are supported by revenue from the gambling industry, which also invests in other public amenities to fulfill the requirements of the Macao government [114,121].

In addition to the current booming tourism industry in Macao, improving the tourists’ impression of the city through beautification has become an important topic in Macao. The development of the design and visual arts industries can provide services to meet the above demands in Macao. Besides gambling entertainment and historic city visiting, adding performing arts becomes an important tourism option for tourists, which enriches the visual feast for tourists under the differentiated management concept of the performing arts in hotels. Perfect digital media planning is also helpful for visitors to enable them to check the necessary information before their trip and to establish a good first impression of the city.

In addition, by adding a heritage management unit, a closer connection will be established between CCIs and the tourism industry, and, to be more specific, one can include exhibition and performance venues for the CCIs via the reactivation of old districts. Furthermore, the tourism industry also enriches the tour options for tourists due to the activation application of old areas, which can provide more job opportunities for the local design industry and drive the development of the design industry through demand for landscape beautification.

Those five industries, including the clothing, pop music, film, animation, and publishing industries, with the lack of a complete industrial chain in Macao, are suggested to supply one segment of service in the industrial chain, or they are advised to focus on the establishment of the city image of Macao in the future. In addition, the current goal of these five industries is to develop and strengthen small cultural enterprises, rather than large-scale cultural industries. For example, Macao can act as a scene provider for the film industry to provide a rare Portuguese-style scene in Asia. Macao’s unique designers can also provide niche design services to the clothing industry. Thus, the present goals at each stage for such industries are advised to be to develop and strengthen small-scale cultural undertakings, instead of developing large-scale cultural industries.

5.4. Summary