Grazing Land Productivity, Floral Diversity, and Management in a Semi-Arid Mediterranean Landscape

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

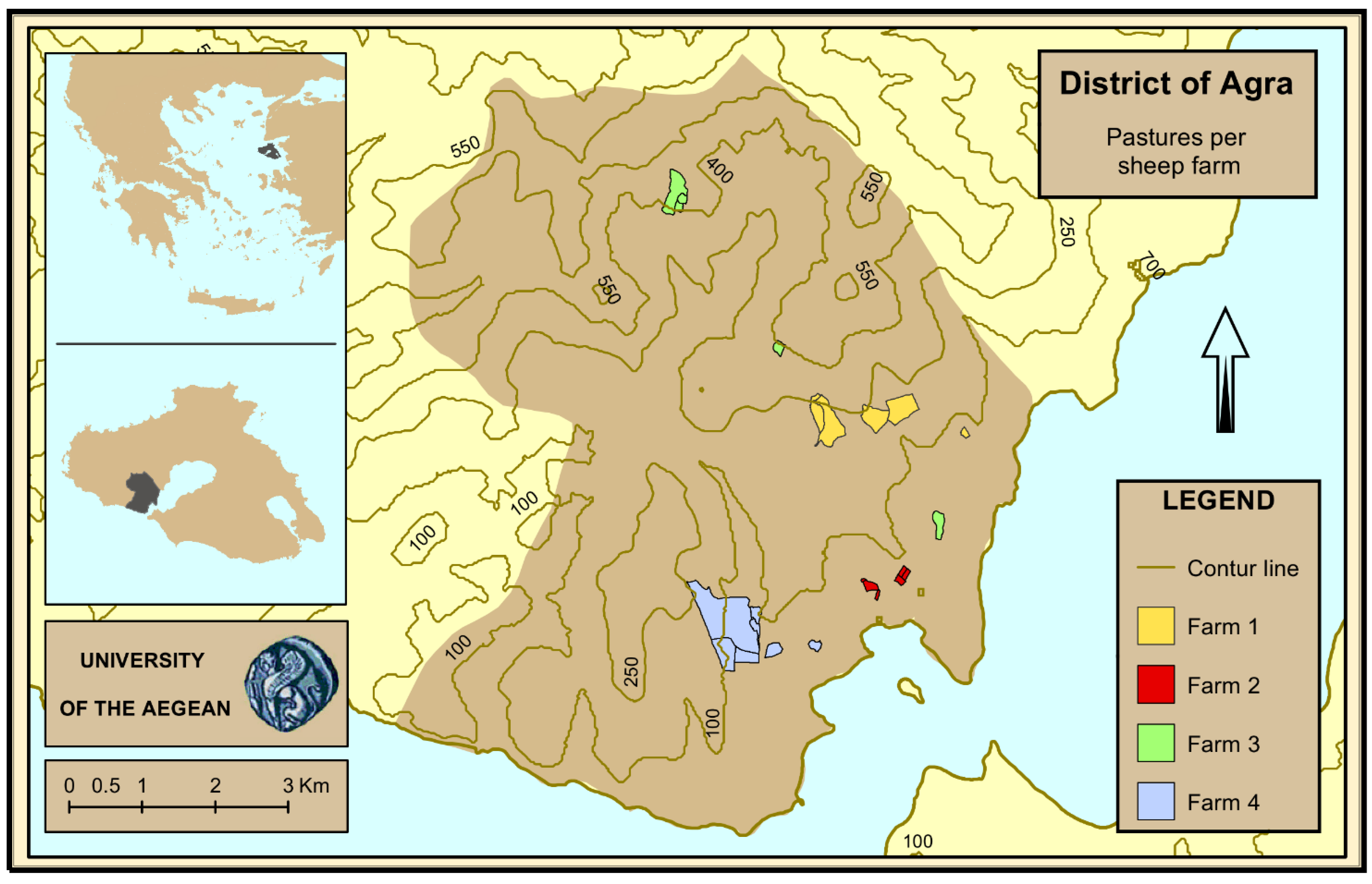

2.1. Study Site

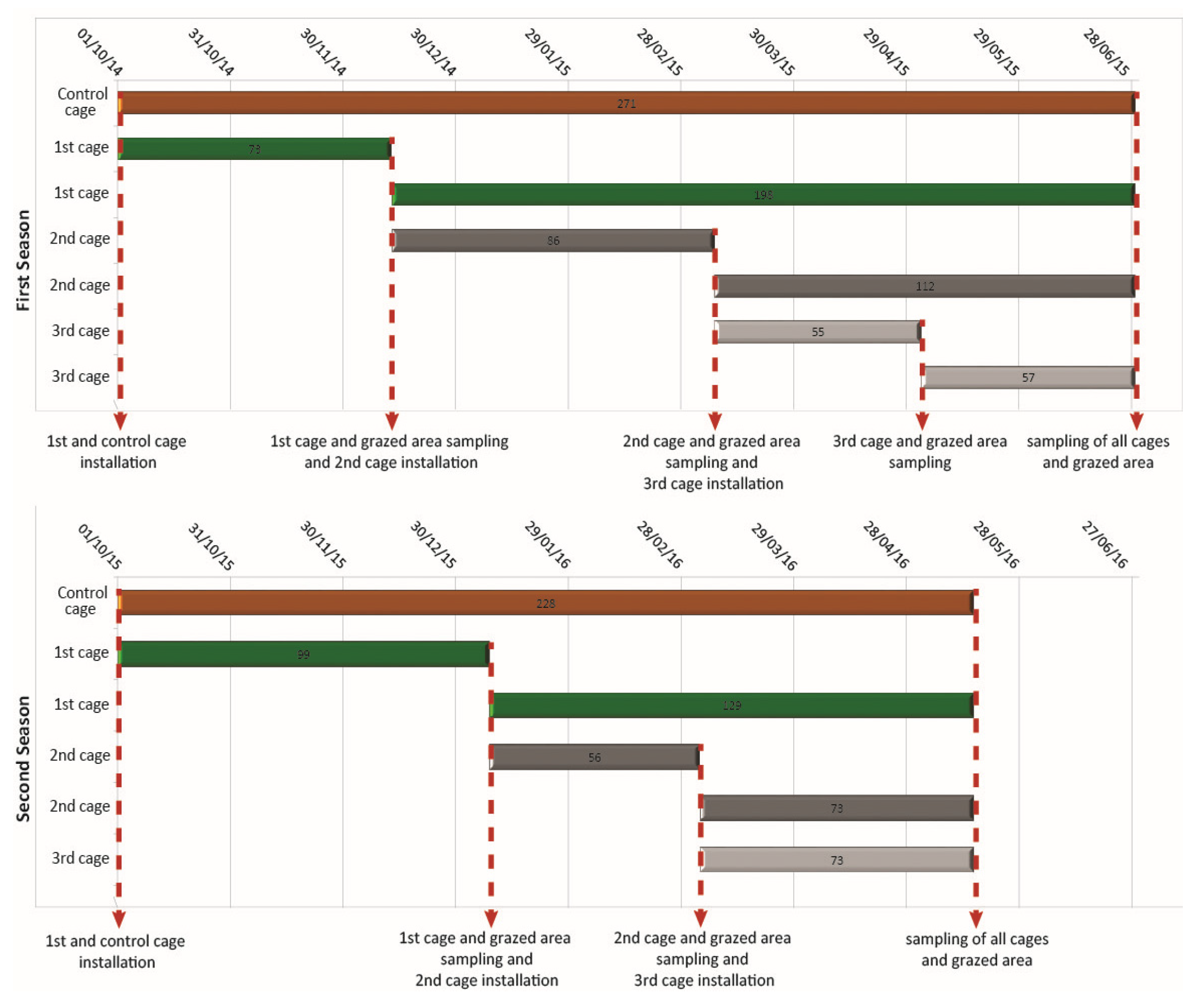

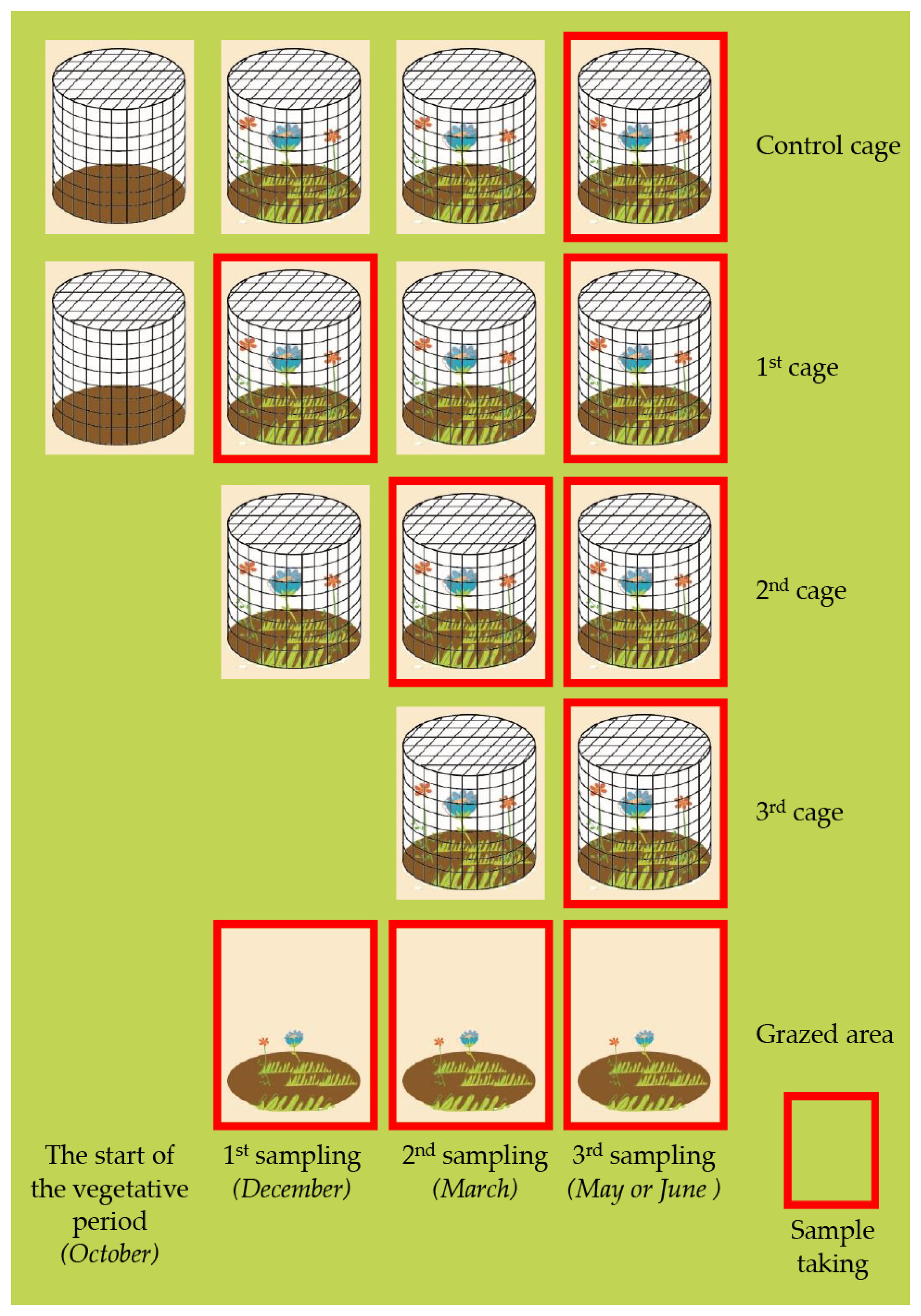

2.2. Research Methods

- herbage biomass;

- land cover;

- species richness of herbaceous plant communities;

- chemically analyses of the biomass for ash, crude protein, and crude fiber.

2.3. Analysis

- Type of pasture: shows if the pastures are undisturbed or if there have been actions by farmers to improve them. The improvement of grazing land is by making terraces, removing rocks and undesirable plants, this usually stands for the land which has changed use, most of the time from arable land to pastures.

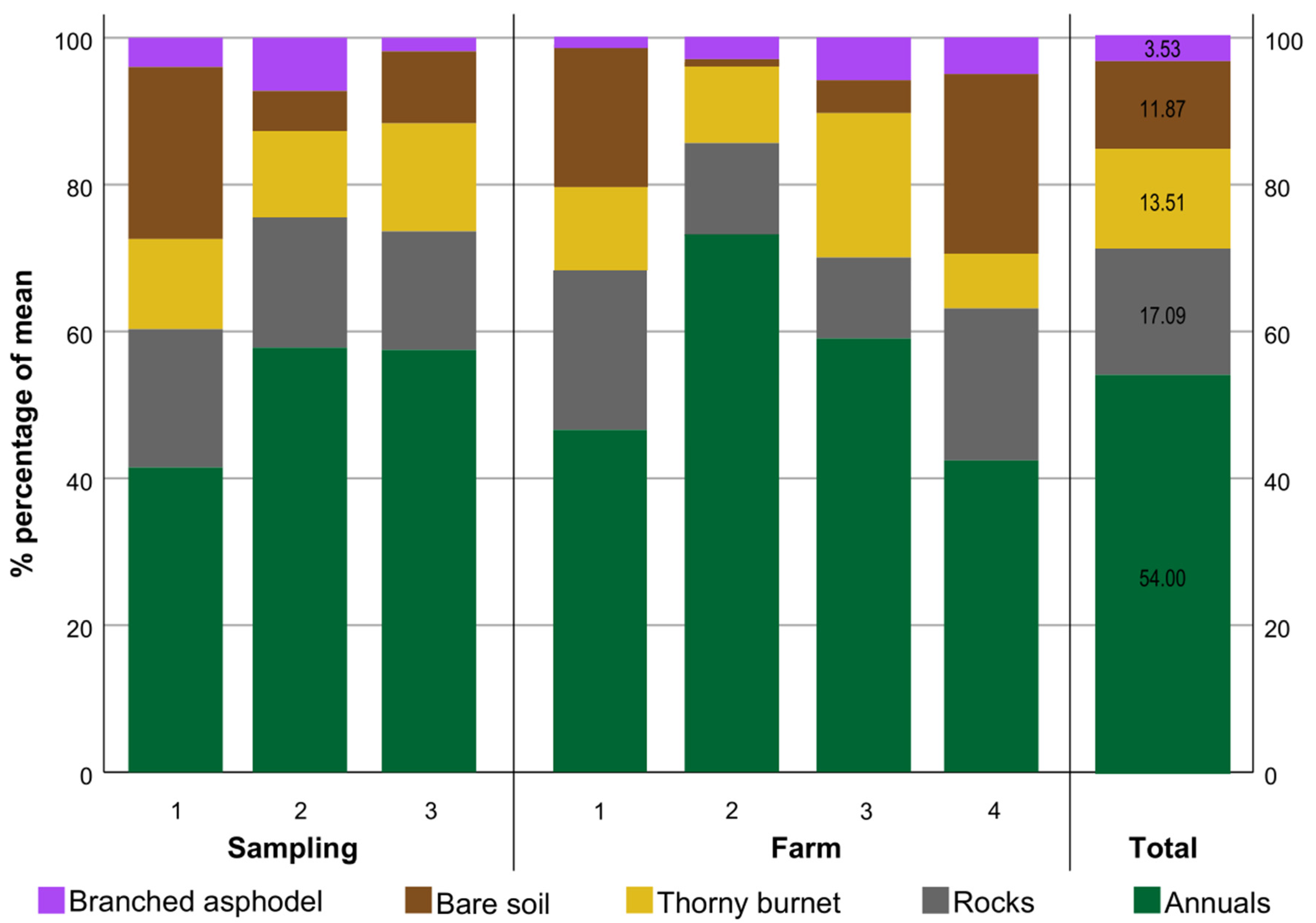

- Land cover classes: the land cover was recorded in five classes as % of total cover: bare soil, annuals, rocks, S. spinosum, Asphodelous ramosus.

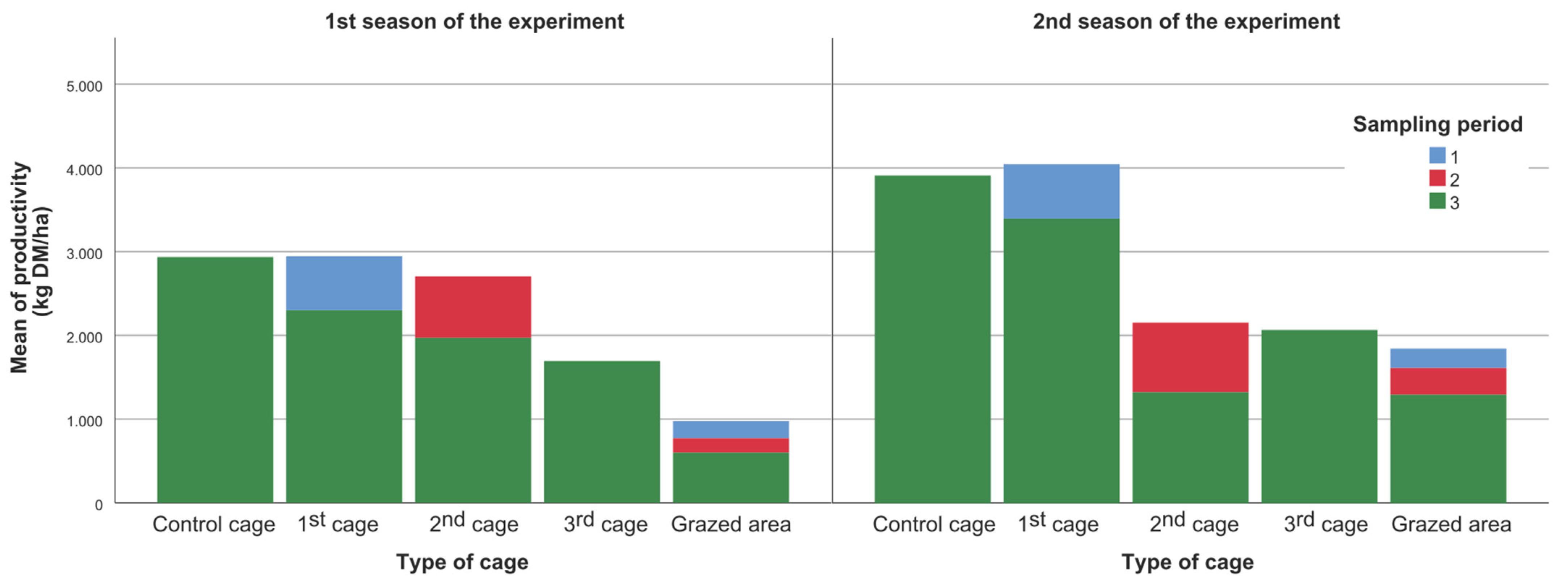

- Productivity (kg dm/ha): expresses the productivity of herbaceous dry mass per hectare as calculated by multiplying the biomass produced by each cage by the percentage of herbaceous biomass coverage of each pasture. This productivity was assumed to be homogenous for the pastures in the cases of a single sampling cage, while in pastures with more than one sampling point, the average productivity of all sampling points was used.

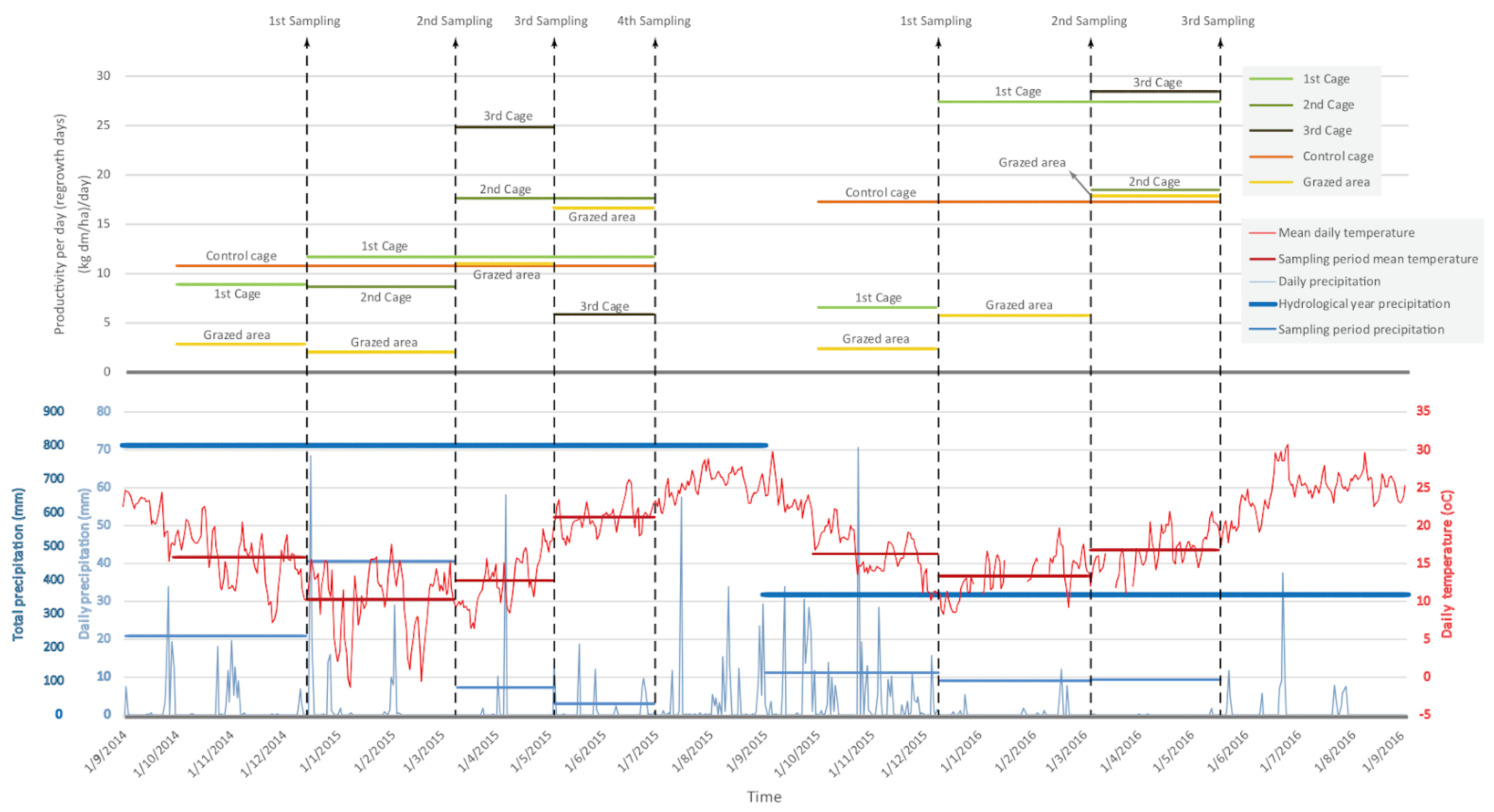

- Productivity per day (regrowth days) ((kg dm/ha)/day): Productivity/Regrowth days: expresses the productivity of herbaceous dry mass per hectare and per day for the period that each sampling represents (all days appear in Figure 2).

- Grazing pressure ((animals/ha)/day): grazing practices have been provided by the farmers for the whole grazing period as the adult animals that grazed a pasture for 15-day intervals. This implied that the shortest grazing period for each pasture is 15 days and up to the whole period.

- Dry matter/sheep/day ((kg dm)/day): expresses the dry matter that was available to the animals that were on the pasture per day for the days that the pasture was grazed.

- Number of different species (N): expresses the total number of the different species recognized, classified in families, and more general to grasses, legumes, and other families.

- Herbage nutritional quality is measured as % of total dry matter content in proteins, ash, and crude fiber.

3. Results

3.1. Precipitation and Land Cover

3.2. Biomass Production, Productivity, and Grazing Practices

3.3. Plant Species, Diversity, and Protein Content

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Season 1 | Season 2 | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pasture | Control Cage | 1st Cage | 2nd Cage | 3rd Cage | Grazed Area | Control Cage | 1st Cage | 2nd Cage | 3rd Cage | Grazed Area |

| 1.1 | 16 | 15 | 15 | 11 | 25 | 11 | 8 | 9 | 11 | 14 |

| 2.1 | 18 | 22 | 23 | 23 | 30 | 6 | 15 | 15 | 11 | 13 |

| 2.2 | 6 | 13 | 6 | 9 | 9 | 5 | 8 | 4 | 4 | 5 |

| 1.2 | 5 | 12 | 8 | 8 | 7 | 4 | 3 | 9 | 11 | 4 |

| 3.1 | 14 | 12 | 16 | 18 | 12 | 7 | 5 | 4 | 5 | 7 |

| 4.1 | 14 | 14 | 6 | 8 | 9 | 5 | 9 | 6 | 8 | 2 |

| 4.2 | 9 | 9 | 11 | 21 | 8 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 5 |

| 1.3 | 23 | 7 | 15 | 15 | 16 | 23 | 10 | 11 | 7 | 8 |

| 3.2 | 13 | 8 | 11 | 16 | 10 | 5 | 4 | 8 | 6 | 6 |

| 2.3 | 10 | 9 | 11 | 13 | 11 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 6 | 8 |

| 4.3 | 39 | 22 | 25 | 18 | 29 | 15 | 14 | 15 | 17 | 21 |

| 1.4 | 10 | 8 | 10 | 5 | 5 | 13 | 8 | 4 | 8 | 6 |

| 3.3 | 17 | 28 | 20 | 37 | 18 | 10 | 7 | 8 | 13 | 12 |

| 4.4 | 12 | 13 | 6 | 4 | 15 | 7 | 7 | 4 | 5 | 5 |

| Families | Number of Species | |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Poaceae | 19 |

| 2 | Compositae | 26 |

| 3 | Fabaceae | 17 |

| 4 | Plantaginaceae | 5 |

| 5 | Caryophyllaceae | 11 |

| 6 | Umbelliferae | 9 |

| 7 | Liliaceae | 4 |

| 8 | Boraginaceae | 3 |

| 9 | Xanthorrhoeaceae | 2 |

| 10 | Polygonaceae | 4 |

| 11 | Geraniaceae | 6 |

| 12 | Brassicaceae | 2 |

| 13 | Gentianaceae | 2 |

| 14 | Apiaceae | 2 |

| 15 | Ranunculaceae | 3 |

| 16 | Hyacinthaceae | 2 |

| 17 | Lamiaceae | 3 |

| 18 | Rosaceae | 2 |

| 19 | Amaranthaceae | 1 |

| 20 | Cruciferae | 1 |

| 21 | Orobanchaceae | 1 |

| 22 | Malvaceae | 1 |

| 23 | Scrophulariaceae | 2 |

| 24 | Caprifoliaceae | 1 |

| 25 | Lythraceae | 1 |

| 26 | Oxalidaceae | 1 |

| 27 | Primulaceae | 1 |

| Total | 132 | |

References

- Blondel, J. The ‘Design’ of Mediterranean Landscapes: A Millennial Story of Humans and Ecological Systems during the Historic Period. Hum. Ecol. 2006, 34, 713–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perevolotsky, A.; Seligman, N.G. Role of grazing in mediterranean rangeland ecosystems. Bioscience 1998, 48, 1007–1017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pardini, R. Effects of forest fragmentation on small mammals in an Atlantic Forest landscape. Biodivers. Conserv. 2004, 13, 2567–2586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jouven, M.; Lapeyronie, P.; Moulin, C.H.; Bocquier, F. Rangeland utilization in Mediterranean farming systems. Animal 2010, 4, 1746–1757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Le Houerou, H.N. Impact Of Man And His Animals On Mediterranean Vegetation. In Ecosystems of the World. Mediterranean-Type Shrublands; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1981; pp. 479–521. [Google Scholar]

- Hadjigeorgiou, I.; Osoro, K.; De Almeida, J.F.; Molle, G. Southern European grazing lands: Production, environmental and landscape management aspects. Livest. Prod. Sci. 2005, 96, 51–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Porqueddu, C.; Melis, R.A.M.; Franca, A.; Sanna, F.; Hadjigeorgiou, I.; Casasús, I. Grassland Resources for Extensivefarming Systems in Marginal Lands: Major Drivers and Future Scenarios. In Proceedings of the Organising Committee of the 19th Symposium of the European Grassland Federation, CNR-ISPAAM Istituto Sistema Produzione Animale Ambiente Mediterraneo, Traversa La Crucca 3, Sassari, Italy, 7–10 May 2017; Volme 22, pp. 3–22. [Google Scholar]

- Caballero, R.; Fernández-González, F.; Badia, R.P.; Molle, G.; Roggero, P.P.; Bagella, S.; D’Ottavio, P.; Papanastasis, V.P.; Fotiadis, G.; Sidiropoulou, A.; et al. Grazing Systems and Biodiversity in Mediterranean Areas: Spain, Italy and Greece. Rev. Pastos 2009, 39, 9–154. [Google Scholar]

- Hadjigeorgiou, I. Past, present and future of pastoralism in Greece. Pastor. Res. Policy Pract. 2011, 1, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Veen, P.; Jefferson, R.; de Smidt, J.; van der Straaten, J. Grasslands in Europe of High Nature Value; KNNV Publishing: Zeist, The Netherlands, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Oppermann, R.; Beaufoy, G.; Jones, G. High Nature Value Farming in Europe: 35 European Countries-Experiences And Perspectives; Verlag Regionalkultur: Ubstadt-Weiher, Germany, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Porqueddu, C.; Tavares de Sousa, M.M. Sustainable Mediterranean Grasslands and Their Multi-Functions. In Options Méditerranéennes: Série A. Séminaires Méditerranéens; Montpellier (France) CIHEAM: Zaragoza, Spain, 2008; Volume 79. [Google Scholar]

- Cosentino, S.L.; Porqueddu, C.; Copani, V.; Patané, C.; Testa, G.; Scordia, D.; Melis, R. EGF at 50: The Future of European Grasslands, Proceedings of the Organising Committee of the 25th General Meeting of the European Grassland Federation IBERS, Aberystwyth University, Gogerddan, Aberystwyth, Wales, 7–11 September 2014; Hopkins, A., Collins, R.P., Fraser, M.D., King, V.R., Lloyd, D.C., Moorby, J.M., Robson, P.R.H., Eds.; IBERS, Aberystwyth University: Aberystwyth, UK; Volume 19, pp. 41–56.

- Ligda, C.; Casabianca, F. Adding value to local breeds: Challenges, strategies and key factors. Anim. Genet. Resour. 2013, 53, 107–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kominakis, A.; Tarsani, E.; Hager-Theodorides, A.L.; Mastranestasis, I.; Gkelia, D.; Hadjigeorgiou, I. Genetic differentiation of mainland-island sheep of Greece: Implications for identifying candidate genes for long-term local adaptation. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0257461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zapata, V.M.; Robledano, F. Assessing biodiversity and conservation value of forest patches secondarily fragmented by urbanisation in semiarid southeastern Spain. J. Nat. Conserv. 2014, 22, 166–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plieninger, T.; Hartel, T.; Martín-López, B.; Beaufoy, G.; Bergmeier, E.; Kirby, K.; Montero, M.J.; Moreno, G.; Oteros-Rozas, E.; van Uytvanck, J. Wood-pastures of Europe: Geographic coverage, social–ecological values, conservation management, and policy implications. Biol. Conserv. 2015, 190, 70–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huyghe, C.; de Vliegher, A.; van Gils, B.; Peeters, A. Grasslands and Herbivore Production in Europe and Effects of Common Policies; Editions Quae: Versailles, France, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Snaydon, R.W. World Animal Science. In Grazing Animals; Morley, F.H.W., Ed.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1981; pp. 13–31. [Google Scholar]

- Caredda, S.; Porqueddu, C.; Roggero, P.P.; Sanna, A. Feed resources and feed requirements in the sheep agro-pastoral system of Sardinia. In Proceedings of the IV International Rangeland Congress, Montpellier, France, 22–26 April 1991; pp. 734–737. [Google Scholar]

- Guerreiro, O.; Dentinho, M.T.P.; Moreira, O.C.; Guerra, A.R.; Ramos, P.A.B.; Bessa, R.J.B.; Duarte, M.F.; Jerónimo, E. Potential of Cistus ladanifer L. (rockrose) in small ruminant diets—Effect of season and plant age on chemical composition, in vitro digestibility and antioxidant activity. Grass Forage Sci. 2016, 71, 437–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsiourlis, G.; Konstantinidis, P.; Xofis, P. Taxonomy and ecology of phryganic communities with Sarcopoterium spinosum (L.) Spach of the Aegean (Greece). Isr. J. Plant Sci. 2007, 55, 15–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papanastasis, V.P.; Yiakoulaki, M.D.; Decandia, M.; Dini-Papanastasi, O. Integrating woody species into livestock feeding in the Mediterranean areas of Europe. Anim. Feed Sci. Technol. 2008, 140, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarovali, M.P.; Yiakoulaki, M.D.; Papanastasis, V.P. Effects of shrub encroachment on herbage production and nutritive value in semi-arid Mediterranean grasslands. Grass Forage Sci. 2007, 62, 355–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bailey, D.W.; Dumont, B.; WallisDeVries, M.F. Utilization of heterogeneous grasslands by domestic herbivores: Theory to management. Ann. Zootech. 1998, 47, 321–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kramer, K.; Groen, T.A.; van Wieren, S.E. The interacting effects of ungulates and fire on forest dynamics: An analysis using the model FORSPACE. For. Ecol. Manag. 2003, 181, 205–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sternberg, M.; Gutman, M.; Perevolotsky, A.; Ungar, E.D.; Kigel, J. Vegetation response to grazing management in a Mediterranean herbaceous community: A functional group approach. J. Appl. Ecol. 2000, 37, 224–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Adler, P.; Raff, D.; Lauenroth, W. The effect of grazing on the spatial heterogeneity of vegetation. Oecologia 2001, 128, 465–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perevolotsky, V.I. Integrating landscape ecology in the conservation of Mediterranean ecosystems: The Israeli experience. Isr. J. Plant Sci. 2005, 53, 203–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rook, J.; Tallowin, J.R.B. Grazing and pasture management for biodiversity benefit. Anim. Res. 2003, 52, 181–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Clergue, B.; Amiaud, B.; Pervanchon, F.; Lasserre-Joulin, F.; Plantureux, S. Biodiversity: Function and assessment in agricultural areas. A review. Agron. Sustain. Dev. 2005, 25, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodapp, D.; Borer, E.T.; Harpole, W.S.; Lind, E.M.; Seabloom, E.W.; Adler, P.B.; Alberti, J.; Arnillas, C.A.; Bakker, J.D.; Biederman, L.; et al. Spatial heterogeneity in species composition constrains plant community responses to herbivory and fertilisation. Ecol. Lett. 2018, 21, 1364–1371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Milchunas, G.; Lauenroth, W.K. Quantitative Effects of Grazing on Vegetation and Soils Over a Global Range of Environments. Ecol. Monogr. 1993, 63, 327–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borer, T.; Seabloom, E.W.; Gruner, D.S.; Harpole, W.S.; Hillebrand, H.; Lind, E.M.; Adler, P.B.; Alberti, J.; Anderson, T.M.; Bakker, J.D.; et al. Herbivores and nutrients control grassland plant diversity via light limitation. Nature 2014, 508, 517–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Safriel, U.N. Water Scarcity, Land Degradation and Desertification in the Mediterranean Region. In NATO Science for Peace and Security Series C: Environmental Security; Rubio, J.L., Safriel, U., Daussa, R., Blum, W., Pedrazzini, F., Eds.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2009; pp. 33–73. [Google Scholar]

- Symeonakis, E.; Karathanasis, N.; Koukoulas, S.; Panagopoulos, G. Monitoring Sensitivity to Land Degradation and Desertification with the Environmentally Sensitive Area Index: The Case of Lesvos Island. Land Degrad. Dev. 2016, 27, 1562–1573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hadjigeorgiou, I.; Zervas, G. The Contributions of Grasslands to the Conservation of Mediterranean Biodiversity; Porqueddu, C., Ríos, S., Eds.; CIHEAM: Zaragoza, Spain, 2010; pp. 35–38. [Google Scholar]

- Kizos, T.; Plieninger, T.; Schaich, H. “Instead of 40 Sheep there are 400”: Traditional Grazing Practices and Landscape Change in Western Lesvos, Greece. Landsc. Res. 2013, 38, 476–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadjigeorgiou, I.; Vaitsis, T.; Laskaridis, G.; Tzanni, C. Restoring Semi-Arid Rangelands on a Greek Aegean Island; Porqueddu, C., de Sousa, M.T., Eds.; CIHEAM: Zaragoza, Spain, 2008; pp. 33–36. [Google Scholar]

- Kosmas, C.; Danalatos, N.G.; Gerontidis, S. The effect of land parameters on vegetation performance and degree of erosion under Mediterranean conditions. Catena 2000, 40, 3–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koutsovili, E.I.; Tzoraki, O.; Theodossiou, N.; Gaganis, P. Numerical assessment of climate change impact on the hydrological regime of a small Mediterranean river, Lesvos Island, Greece. Acta Hortic. Et Regiotect. 2021, 24, 28–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mastranestasis, I.; Ekateriniadou, L.V.; Ligda, C.; Theodorou, K. Genetic diversity and structure of the Lesvos sheep breed. Small Rumin. Res. 2015, 130, 54–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.; Lauenroth, W.K.; Steinhorst, R.K. Review and assessment of various techniques for estimating net aerial primary production in grasslands from harvest data. Bot. Rev. 1975, 41, 181–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, R.A.; Love, R.M. The Step-Point Method of Sampling: A Practical Tool in Range Research. J. Range Manag. 1957, 10, 208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimopoulos, P.; Raus, T.; Constantinidis, T.; Iatrou, G. Vascular Plants of Greece: An Annotated Checklist, Englera; Botanischer Garten und Botanisches Museum: Dahlem, Germany, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Dimopoulos, P.; Raus, T.; Bergmeier, E.; Constantinidis, T.; Iatrou, G.; Kokkini, S.; Strid, A.; Tzanoudakis, D. Vascular plants of Greece: An annotated checklist. Supplement. Willdenowia 2016, 46, 301–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Arianoutsou-Faraggitaki, M. Desertification by overgrazing in Greece: The case of Lesvos island. J. Arid. Environ. 1985, 9, 237–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marathianou, M.; Kosmas, C.; Gerontidis, S.; Detsis, V. Land-use evolution and degradation in Lesvos (Greece): A historical approach. Land Degrad. Dev. 2000, 11, 63–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iosifides, T.; Politidis, T. Socio-economic dynamics, local development and desertification in western Lesvos, Greece. Local Environ. 2005, 10, 487–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osem, Y.; Perevolotsky, A.; Kigel, J. Grazing effect on diversity of annual plant communities in a semi-arid rangeland: Interactions with small-scale spatial and temporal variation in primary productivity. J. Ecol. 2002, 90, 936–946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Lugo, S.; Bermejo, L.A.; de Nascimento, L.; Méndez, J.; Naranjo-Cigala, A.; Arévalo, J.R. Productivity: Key factor affecting grazing exclusion effects on vegetation and soil. Plant Ecol. 2013, 214, 641–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maselli, F.; Argenti, G.; Chiesi, M.; Angeli, L.; Papale, D. Simulation of grassland productivity by the combination of ground and satellite data. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2013, 165, 163–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Isselstein, J.; Griffith, B.A.; Pradel, P.; Venerus, S. Effects of livestock breed and grazing intensity on biodiversity and production in grazing systems. 1. Nutritive value of herbage and livestock performance. Grass Forage Sci. 2007, 62, 145–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papanastasis, V.P.; Mansat, P. Grasslands and related forage resources in Mediterranean areas. In Proceedings of the 16th European Grasslands Federation, Grado, Italy, 15–19 September 1996; pp. 47–57. [Google Scholar]

- Hector, A.; Schmid, B.; Beierkuhnlein, C.; Caldeira, M.C.; Diemer, M.; Dimitrakopoulos, P.G.; Finn, J.A.; Freitas, H.; Giller, P.S.; Good, J.; et al. Plant diversity and productivity experiments in european grasslands. Science 1999, 286, 1123–1127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Troumbis, Y.; Dimitrakopoulos, P.G.; Siamantziouras, A.-S.D.; Memtsas, D. Hidden diversity and productivity patterns in mixed Mediterranean grasslands. Oikos 2000, 90, 549–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimitrakopoulos, P.G.; Galanidis, A.; Siamantziouras, A.-S.D.; Troumbis, A.Y. Short-term invasibility patterns in burnt and unburnt experimental Mediterranean grassland communities of varying diversities. Oecologia 2005, 143, 428–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adamidis, C.; Kazakou, E.; Baker, A.J.M.; Reeves, R.D.; Dimitrakopoulos, P.G. The effect of harsh abiotic conditions on the diversity of serpentine plant communities on Lesbos, an eastern Mediterranean island. Plant Ecol. Divers. 2014, 7, 433–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fraser, L.H.; Pither, J.; Jentsch, A.; Sternberg, M.; Zobel, M.; Askarizadeh, D.; Bartha, S.; Beierkuhnlein, C.; Bennett, J.A.; Bittel, A.; et al. Plant ecology. Worldwide evidence of a unimodal relationship between productivity and plant species richness. Science 2015, 349, 302–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Adler, P.B.; Seabloom, E.W.; Borer, E.T.; Hillebrand, H.; Hautier, Y.; Hector, A.; Harpole, W.S.; O’Halloran, L.R.; Grace, J.B.; Anderson, T.M.; et al. Productivity is a poor predictor of plant species richness. Science 2011, 333, 1750–1753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Alhamad, N. Ecological and species diversity of arid Mediterranean grazing land vegetation. J. Arid Environ. 2006, 66, 698–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giourga, H.; Margaris, N.S.; Vokou, D. Effects of grazing pressure on succession process and productivity of old fields on mediterranean islands. Environ. Manag. 1998, 22, 589–596. [Google Scholar]

- Rutherford, C.; Powrie, L.W. Impacts of heavy grazing on plant species richness: A comparison across rangeland biomes of South Africa. South Afr. J. Bot. 2013, 87, 146–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cingolani, M.; Noy-Meir, I.; Díaz, S. Grazing effects on rangeland diversity: A synthesis of contemporary models. Ecol. Appl. 2005, 15, 757–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aronson, J.; Kigel, J.; Shmida, A.; Klein, J. Adaptive phenology of desert and Mediterranean populations of annual plants grown with and without water stress. Oecologia 1992, 89, 17–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Junttila, O. Plant adaptation to temperature and photoperiod. Agric. Food Sci. 1996, 5, 251–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winner, W.; Pell, E.; Mooney, H. (Eds.) Response of Plants to Multiple Stresses; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

| Sheep | Milk (kg) | Intensity of Production (Milk/Sheep/Year) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Farm 1 | 337 | 56,270 | 167.0 |

| Farm 2 | 248 | 27,832 | 112.2 |

| Farm 3 | 179 | 28,892 | 161.4 |

| Farm 4 | 398 | 38,940 | 97.8 |

| Study area (median) | 184.5 | 15,771 | 85.2 |

| Pasture Indicators | Productivity (kg dm/ha) | Productivity/Regrowth Days (kg dm/ha)/Day | Grazing Pressure (Animals/ha)/Day | Dry Matter/Animal/Day (kg dm)/Day | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pasture | Count | Mean | Standard Error of Mean | Mean | Standard Error of Mean | Mean | Standard Error of Mean | Mean | Standard Error of Mean |

| 1.1 | 18 | 1249.27 | 276.62 | 10.90 | 1.93 | 5.25 | 0.63 | 3.35 | 0.84 |

| 1.2 | 18 | 416.10 | 60.32 | 4.24 | 0.71 | 11.05 | 02.06 | 0.63 | 0.17 |

| 1.3 | 18 | 570.28 | 142.38 | 4.65 | 0.83 | 1.76 | 0.25 | 6.65 | 2.22 |

| 1.4 | 18 | 274.06 | 79.45 | 2.32 | 0.70 | 13.16 | 0.57 | 0.17 | 0.05 |

| 2.1 | 18 | 2161.01 | 485.67 | 18.80 | 3.53 | 5.30 | 0.48 | 4.80 | 1.21 |

| 2.2 | 18 | 5824.86 | 1273.61 | 49.69 | 9.30 | 43.33 | 2.12 | 1.13 | 0.20 |

| 2.3 | 18 | 1019.10 | 230.22 | 08.07 | 1.11 | 36.20 | 3.79 | 0.34 | 0.08 |

| 3.1 | 18 | 1191.02 | 226.69 | 12.51 | 2.71 | 4.37 | 1.51 | 1.13 | 0.34 |

| 3.2 | 18 | 1360.27 | 306.53 | 11.65 | 2.14 | 9.70 | 02.04 | 1.68 | 0.64 |

| 3.3 | 18 | 2124.49 | 468.53 | 17.45 | 2.93 | 10.06 | 1.23 | 2.71 | 0.80 |

| 4.1 | 18 | 1211.06 | 283.37 | 9.75 | 1.50 | 62.82 | 3.66 | 0.16 | 0.02 |

| 4.2 | 18 | 1594.38 | 301.02 | 14.78 | 2.83 | 11.09 | 2.28 | 1.70 | 0.33 |

| 4.3 | 18 | 351.26 | 87.35 | 3.14 | 0.54 | 1.39 | 0.23 | 2.50 | 0.68 |

| 4.4 | 18 | 320.72 | 93.89 | 03.06 | 0.81 | 01.04 | 0.24 | 2.40 | 0.67 |

| 1st season | 126 | 1250.23 | 199.45 | 9.18 | 1.35 | 16.07 | 1.75 | 1.63 | 0.42 |

| 2nd season | 126 | 1559.46 | 199.16 | 15.25 | 1.69 | 14.86 | 1.74 | 2.66 | 0.32 |

| Total | 252 | 1404.85 | 140.99 | 12.22 | 1.10 | 15.47 | 1.23 | 2.15 | 0.27 |

| Type of Cage | Count | Mean | Std. Deviation | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1st season | Control cage | 14 | 10.83 | 11.36 |

| 1st cage | 28 | 10.22 | 13.63 | |

| 2nd cage | 28 | 13.07 | 21.78 | |

| 3rd cage | 14 | 15.11 | 22.18 | |

| Grazed area | 42 | 3.38 | 3.62 | |

| 2nd season | Control cage | 14 | 17.17 | 11.53 |

| 1st cage | 28 | 16.45 | 25.24 | |

| 2nd cage | 28 | 16.51 | 16.44 | |

| 3rd cage | 14 | 28.34 | 24.02 | |

| Grazed area | 42 | 8.60 | 12.89 | |

| 1st and 2nd season | Control cage | 28 | 14.00 | 11.68 |

| 1st cage | 56 | 13.33 | 20.34 | |

| 2nd cage | 56 | 14.79 | 19.20 | |

| 3rd cage | 28 | 21.72 | 23.67 | |

| Grazed area | 84 | 5.99 | 9.77 |

| Season | Sampling Period | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 3 | ||||||

| Pasture | Mean | Standard Error of Mean | Mean | Standard Error of Mean | Mean | Standard Error of Mean | Mean | Standard Error of Mean | Mean | Standard Error of Mean |

| 1.1 | 6.35 | 0.97 | 4.14 | 0.68 | 8.58 | 0.77 | 6.65 | 0.95 | 3.36 | 0.44 |

| 1.2 | 8.41 | 2.57 | 13.69 | 3.12 | 2.34 | 1.35 | 2.59 | 0.24 | 17.92 | 1.55 |

| 1.3 | 1.47 | 0.41 | 2.05 | 0.26 | 3.20 | 0.05 | 2.21 | 0.21 | 1.01 | 0.19 |

| 1.4 | 13.39 | 0.78 | 12.93 | 0.86 | 9.63 | 0.44 | 12.09 | 0.06 | 15.00 | 0.28 |

| 2.1 | 6.57 | 0.58 | 4.03 | 0.47 | 6.78 | 0.15 | 3.70 | 0.06 | 5.36 | 0.75 |

| 2.2 | 48,00 | 3.43 | 38.66 | 1.38 | 43.62 | 5.69 | 33.02 | 1.06 | 47.34 | 2.08 |

| 2.3 | 46.72 | 1.18 | 25.69 | 5.65 | 43.3 | 2.96 | 49.72 | 0.92 | 27.96 | 5.43 |

| 3.1 | 7.90 | 2.49 | 0.83 | 0.55 | 1.88 | 1.08 | 0.78 | 0.45 | 6.80 | 2.45 |

| 3.2 | 7.09 | 3.29 | 12.31 | 2.27 | 0.43 | 0.25 | 21.09 | 1.22 | 8.86 | 2.06 |

| 3.3 | 10.96 | 1.98 | 9.15 | 1.54 | 1.17 | 0.04 | 11.14 | 0.46 | 13.18 | 0.71 |

| 4.1 | 56.17 | 5.95 | 69.47 | 3.22 | 53.71 | 2.74 | 85.11 | 0.00 | 57.55 | 3.95 |

| 4.2 | 9.14 | 2.59 | 13.04 | 3.81 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 2.82 | 0.44 | 18.84 | 1.59 |

| 4.3 | 1.80 | 0.37 | 0.98 | 0.20 | 1.96 | 0.17 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 1.72 | 0.25 |

| 4.4 | 1.05 | 0.37 | 1.03 | 0.33 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 1.88 | 0.14 |

| Season 1 total | 16.07 | 1.75 | 13.21 | 3.79 | 16.86 | 4,54 | 16.90 | 2.11 | ||

| Season 2 total | 14.86 | 1.74 | 12.01 | 3.34 | 16.13 | 4.54 | 15.49 | 2.20 | ||

| Plant Category | Season | Count | Mean | Minimum | Maximum | Std. Deviation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Grasses | 1st | 126 | 5.60 | 0.00 | 18.00 | 3.11 |

| 2nd | 126 | 3.23 | 0.00 | 11.00 | 2.27 | |

| 1st and 2nd | 252 | 4.41 | 0.00 | 18.00 | 2.96 | |

| Legumes | 1st | 126 | 1.74 | 0.00 | 6.00 | 1.48 |

| 2nd | 126 | 0.40 | 0.00 | 2.00 | 0.55 | |

| 1st and 2nd | 252 | 1.07 | 0.00 | 6.00 | 1.30 | |

| Other families | 1st | 126 | 6.81 | 2.00 | 24.00 | 4.62 |

| 2nd | 126 | 4.43 | 0.00 | 13.00 | 2.69 | |

| 1st and 2nd | 252 | 5.62 | 0.00 | 24.00 | 3.95 |

| Crude Protein | Crude Fiber | Ash | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Type of Cage | Count of Samples | Count of Measurable Samples | Mean | Std. Deviation | Count of Measurable Samples | Mean | Std. Deviation | Count of Measurable Samples | Mean | Std. Deviation |

| Control cage | 28 | 26 | 5.60 | 1.77 | 27 | 32.72 | 3.18 | 27 | 12.02 | 2.91 |

| 1st cage | 28 | 25 | 5.77 | 1.31 | 25 | 32.96 | 2.60 | 26 | 11.34 | 1.81 |

| 2nd cage | 28 | 18 | 6.54 | 2.36 | 20 | 33.06 | 2.92 | 20 | 10.21 | 1.52 |

| 3rd cage | 28 | 14 | 7.27 | 2.18 | 14 | 31.29 | 1.99 | 14 | 10.70 | 2.70 |

| Grazed area | 28 | 23 | 5.49 | 2.13 | 22 | 33.14 | 2.68 | 23 | 10.25 | 1.68 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Psyllos, G.; Hadjigeorgiou, I.; Dimitrakopoulos, P.G.; Kizos, T. Grazing Land Productivity, Floral Diversity, and Management in a Semi-Arid Mediterranean Landscape. Sustainability 2022, 14, 4623. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14084623

Psyllos G, Hadjigeorgiou I, Dimitrakopoulos PG, Kizos T. Grazing Land Productivity, Floral Diversity, and Management in a Semi-Arid Mediterranean Landscape. Sustainability. 2022; 14(8):4623. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14084623

Chicago/Turabian StylePsyllos, Georgios, Ioannis Hadjigeorgiou, Panayiotis G. Dimitrakopoulos, and Thanasis Kizos. 2022. "Grazing Land Productivity, Floral Diversity, and Management in a Semi-Arid Mediterranean Landscape" Sustainability 14, no. 8: 4623. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14084623

APA StylePsyllos, G., Hadjigeorgiou, I., Dimitrakopoulos, P. G., & Kizos, T. (2022). Grazing Land Productivity, Floral Diversity, and Management in a Semi-Arid Mediterranean Landscape. Sustainability, 14(8), 4623. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14084623