Changes in the Price of Food and Agricultural Raw Materials in Poland in the Context of the European Union Accession

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Framework

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Study Area

3.2. Data

3.3. Method of Data Analysis

4. Results

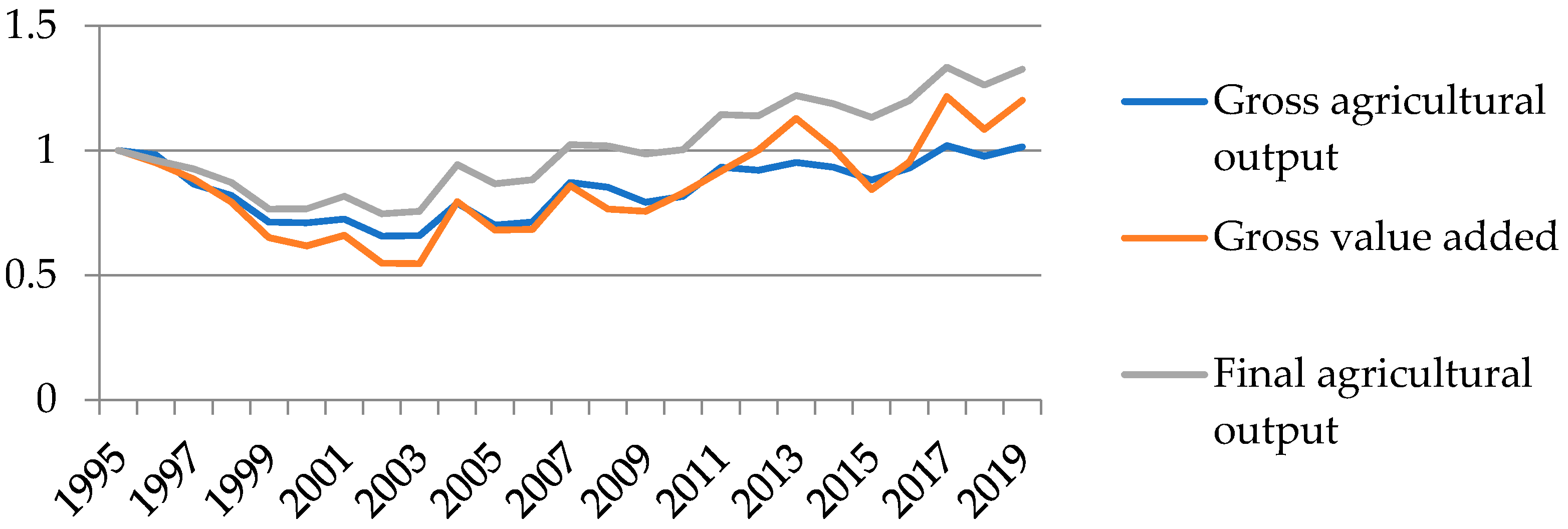

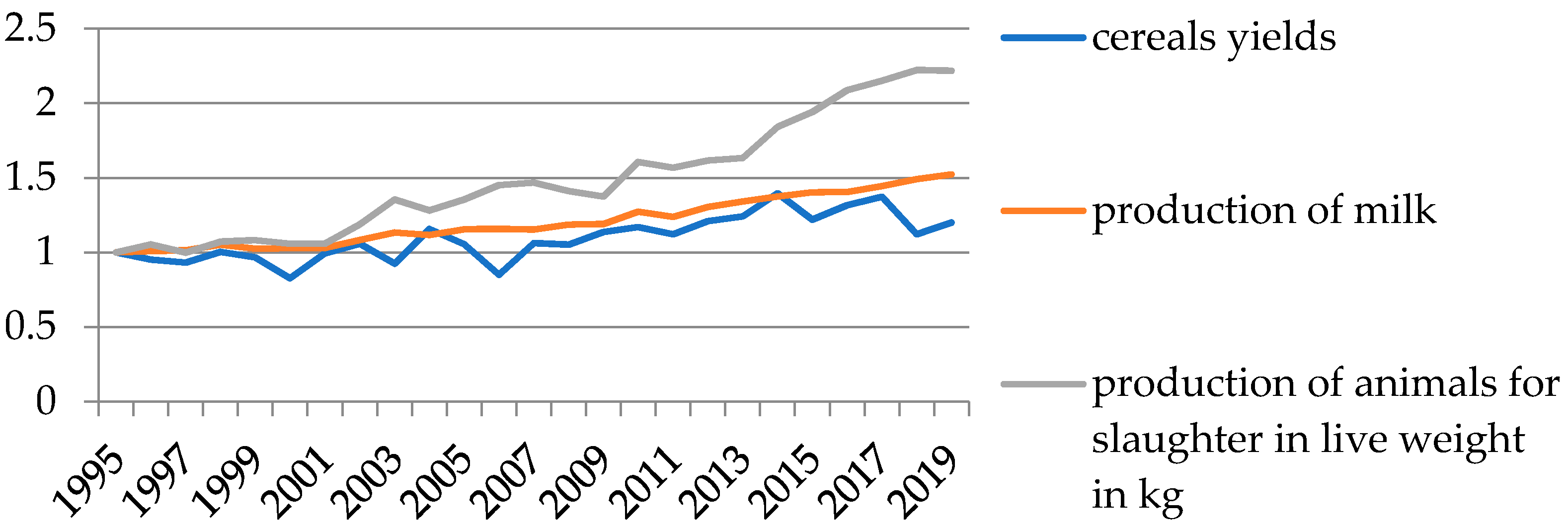

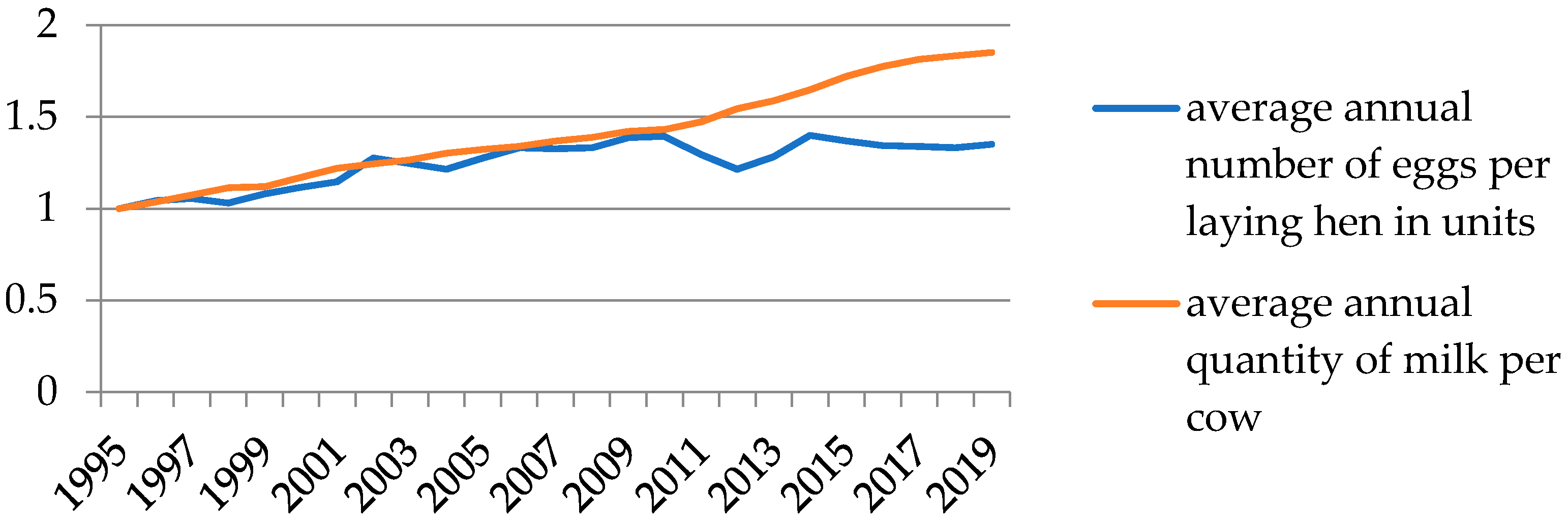

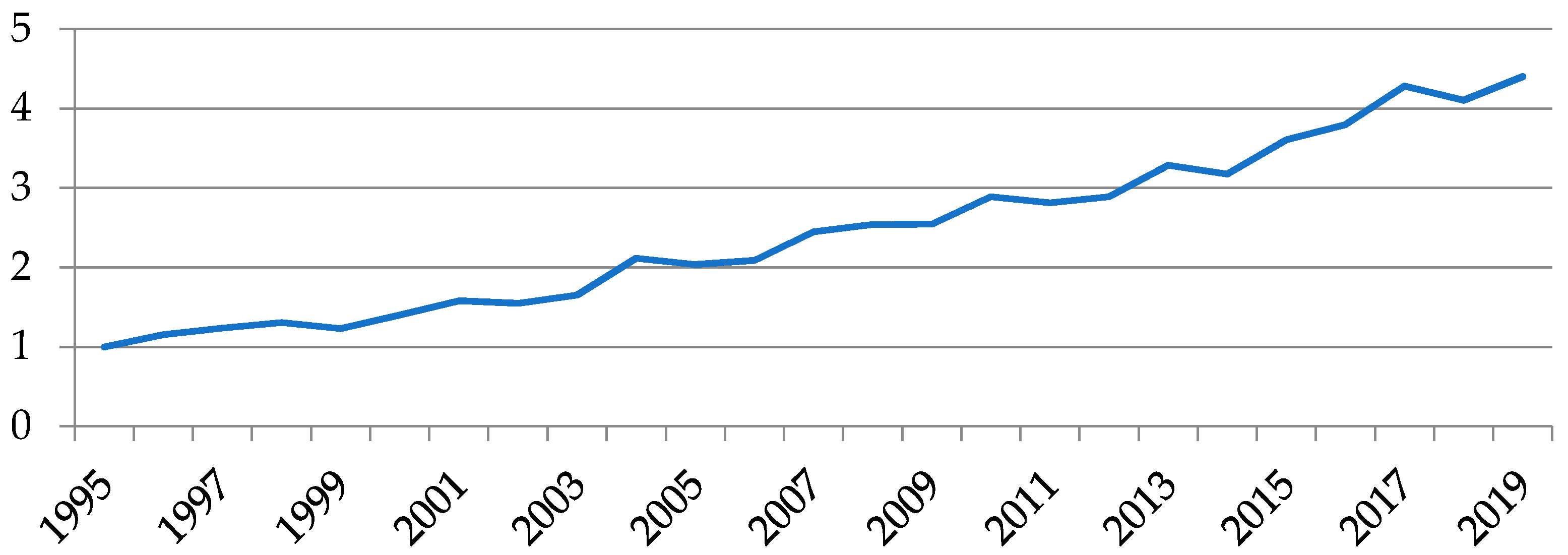

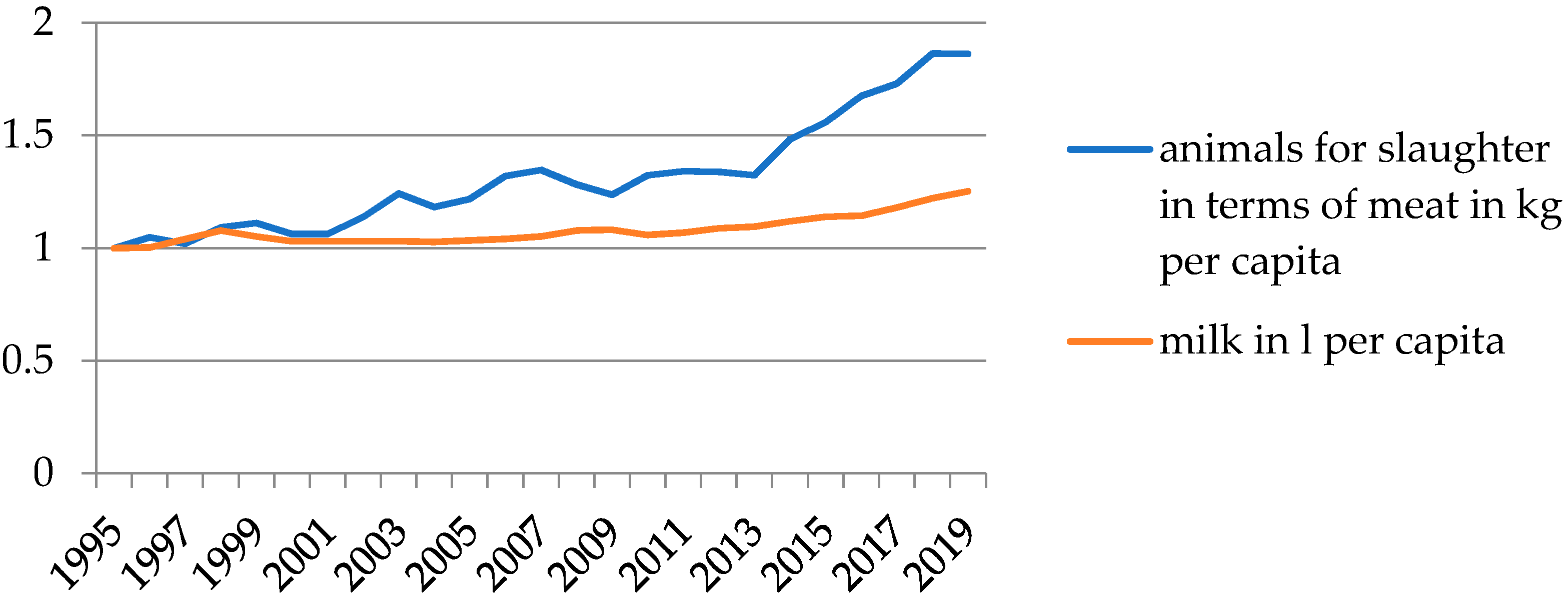

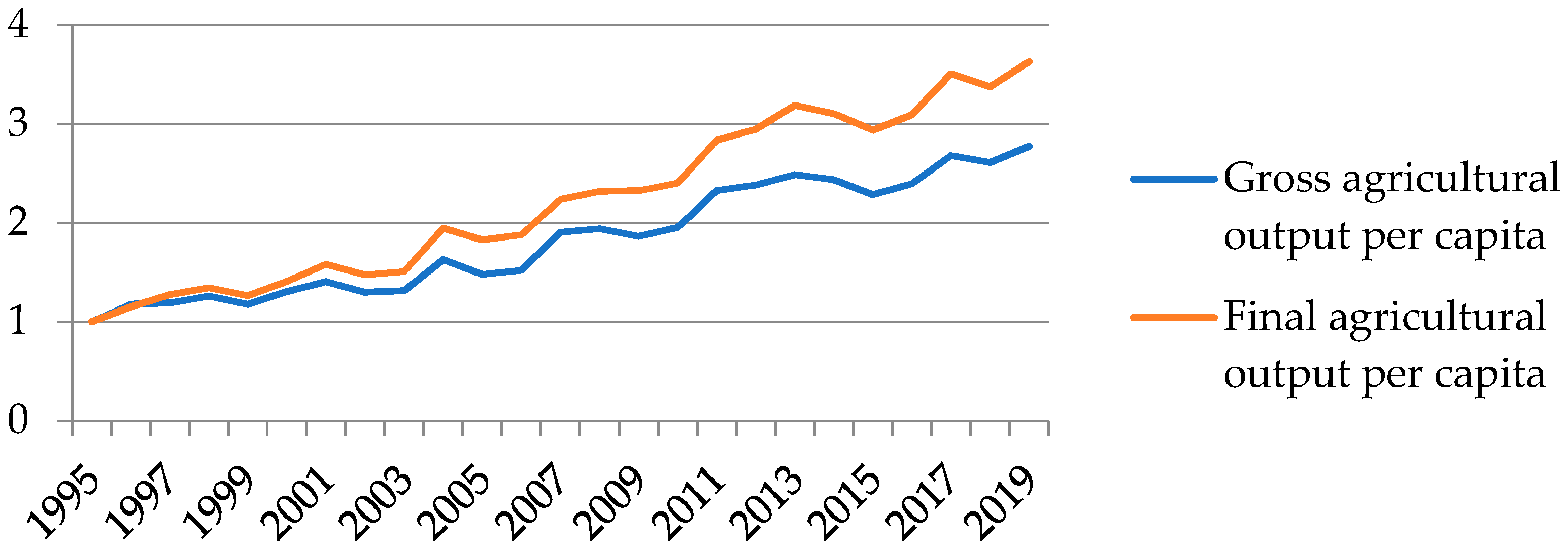

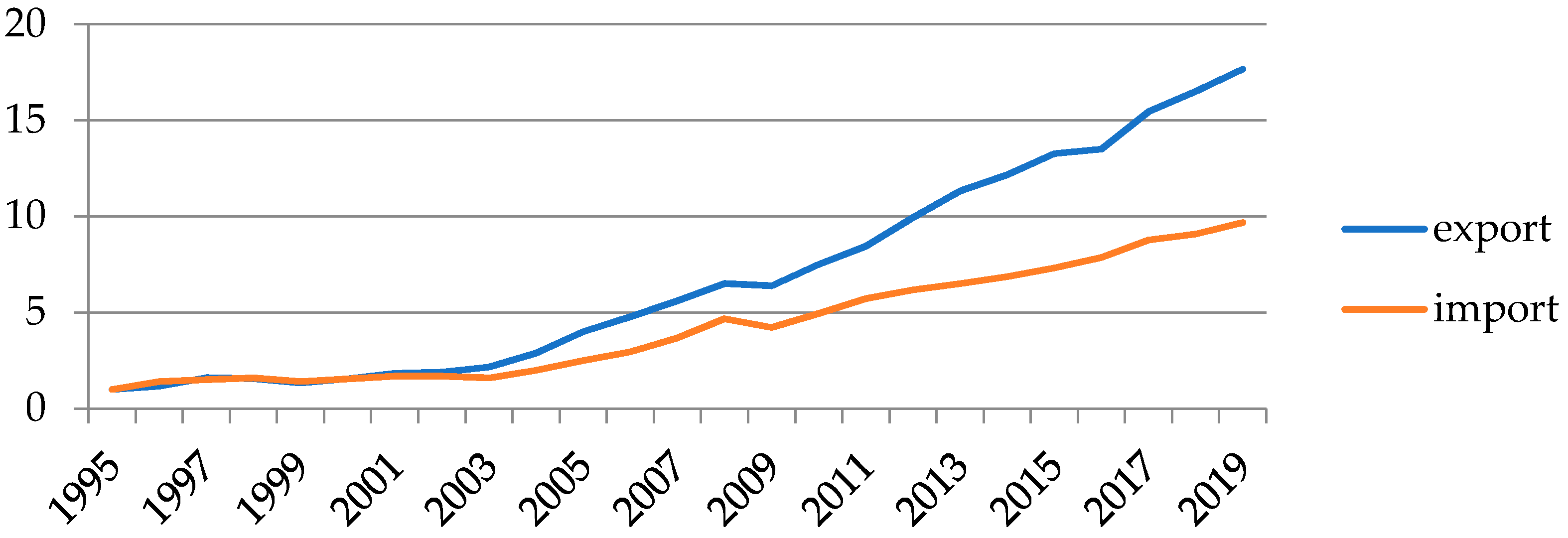

4.1. Changes in the Agriculture in Poland after Accession to the EU

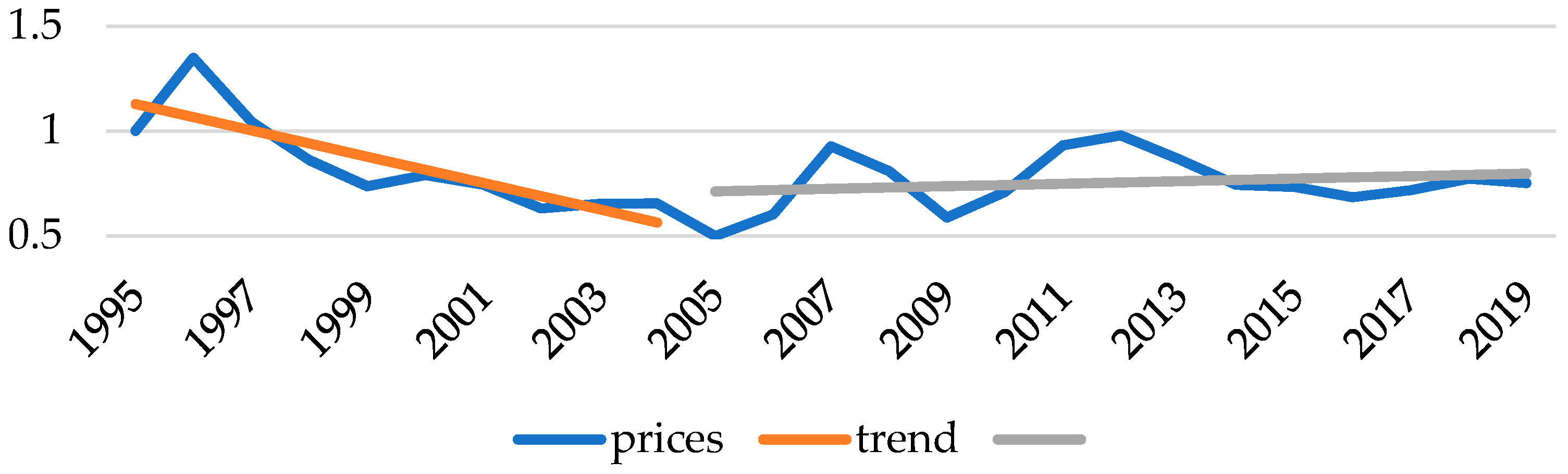

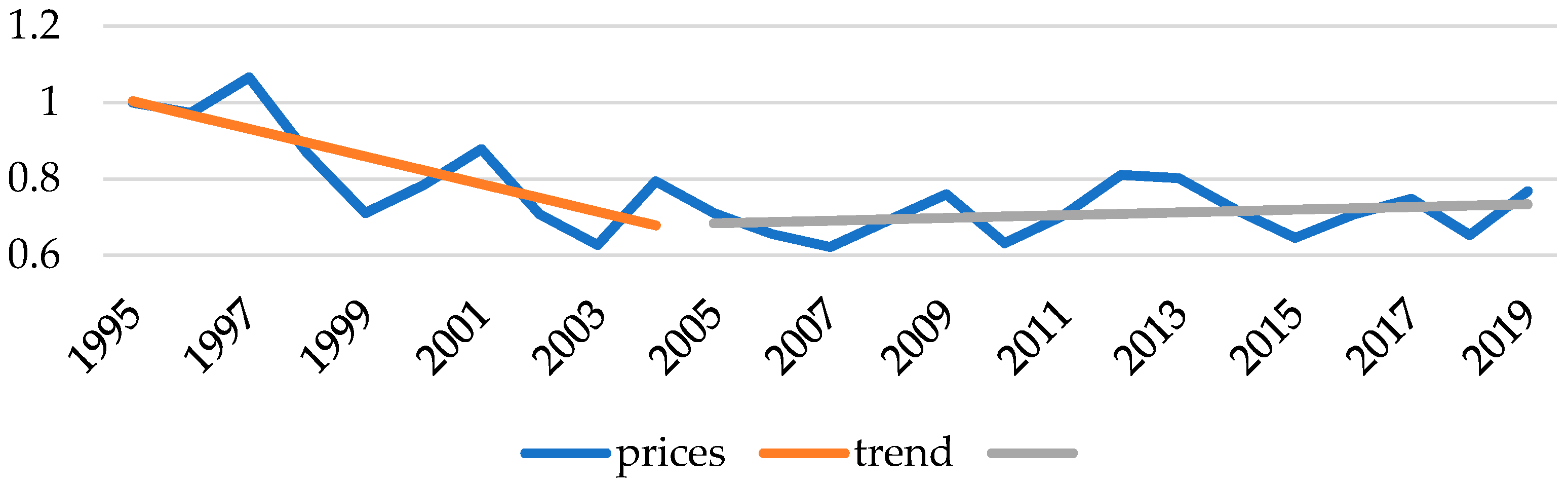

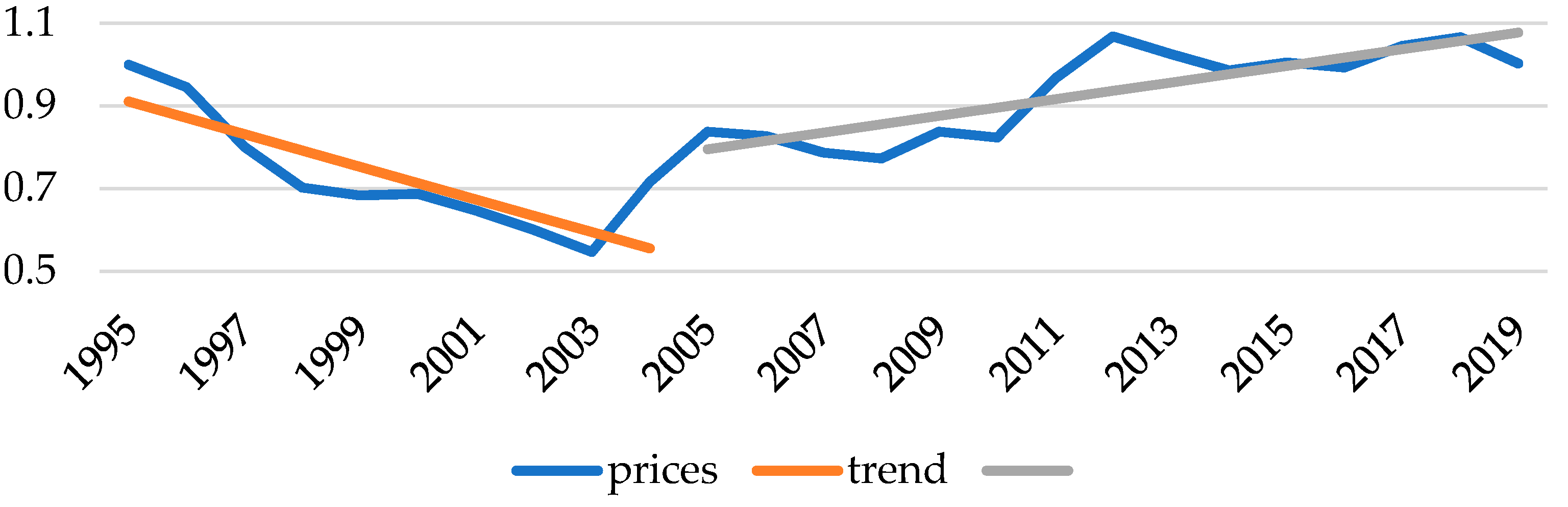

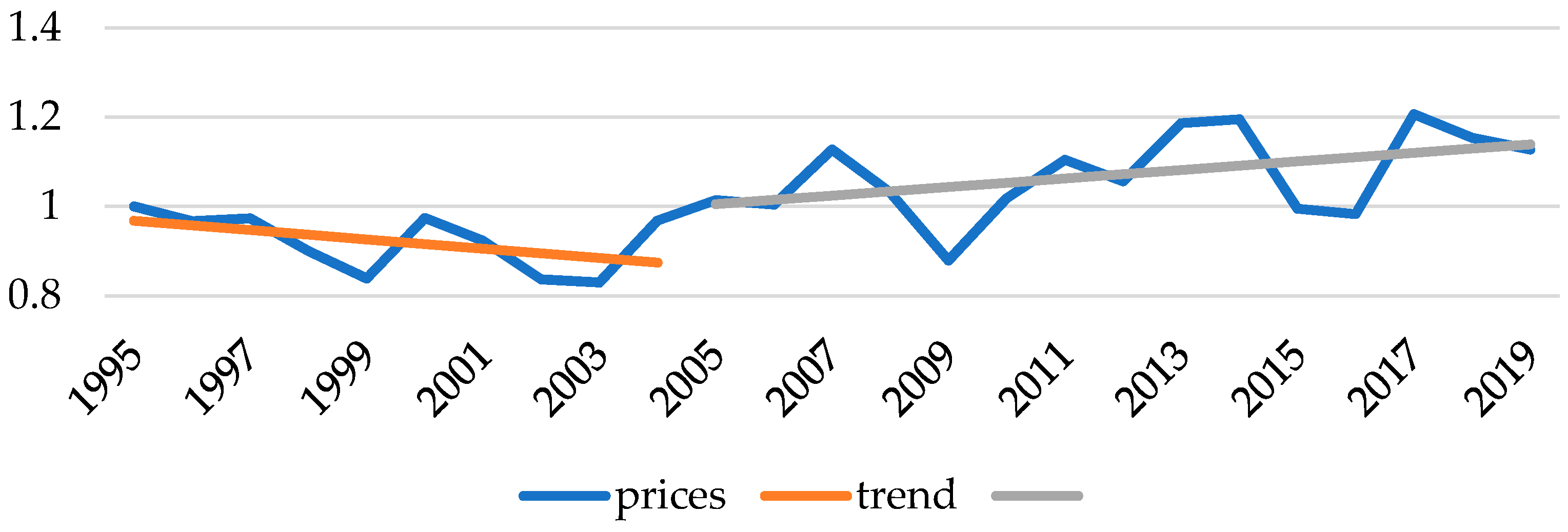

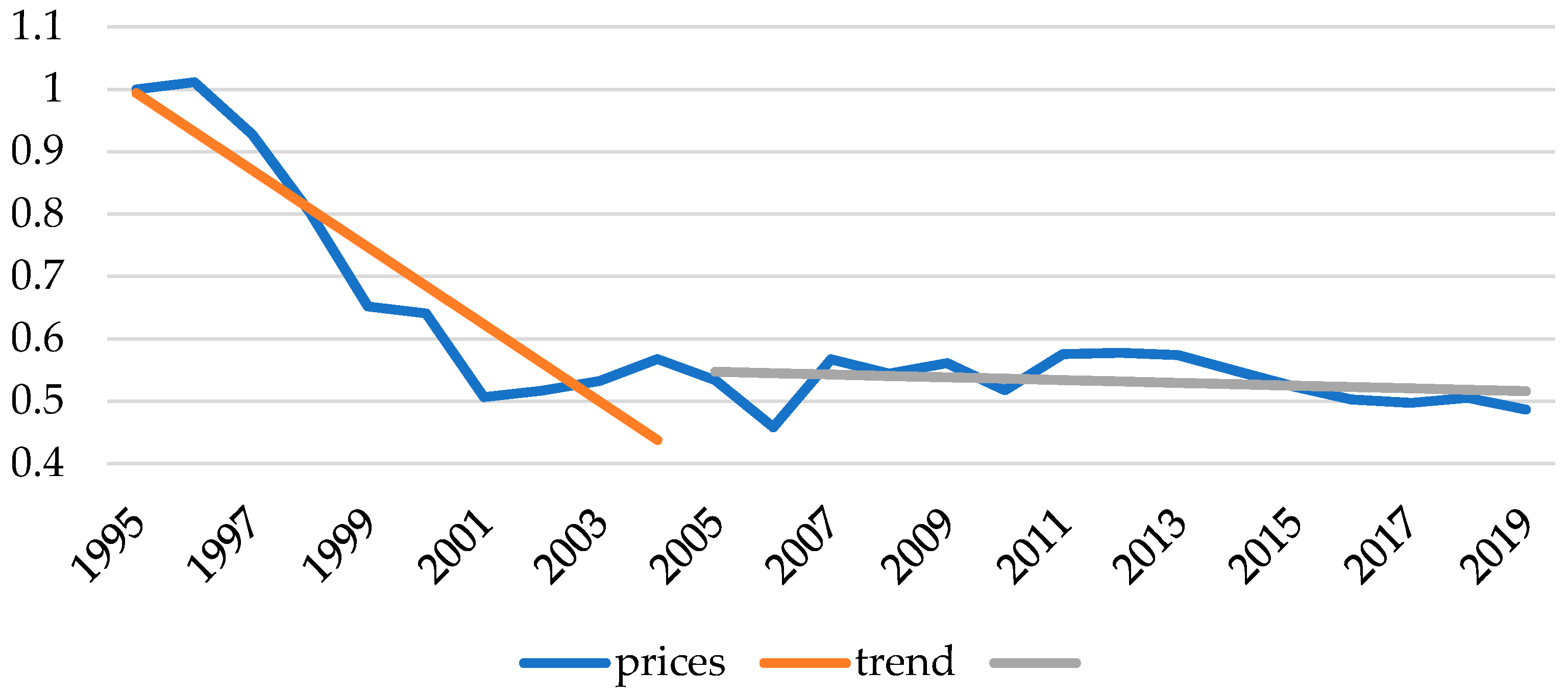

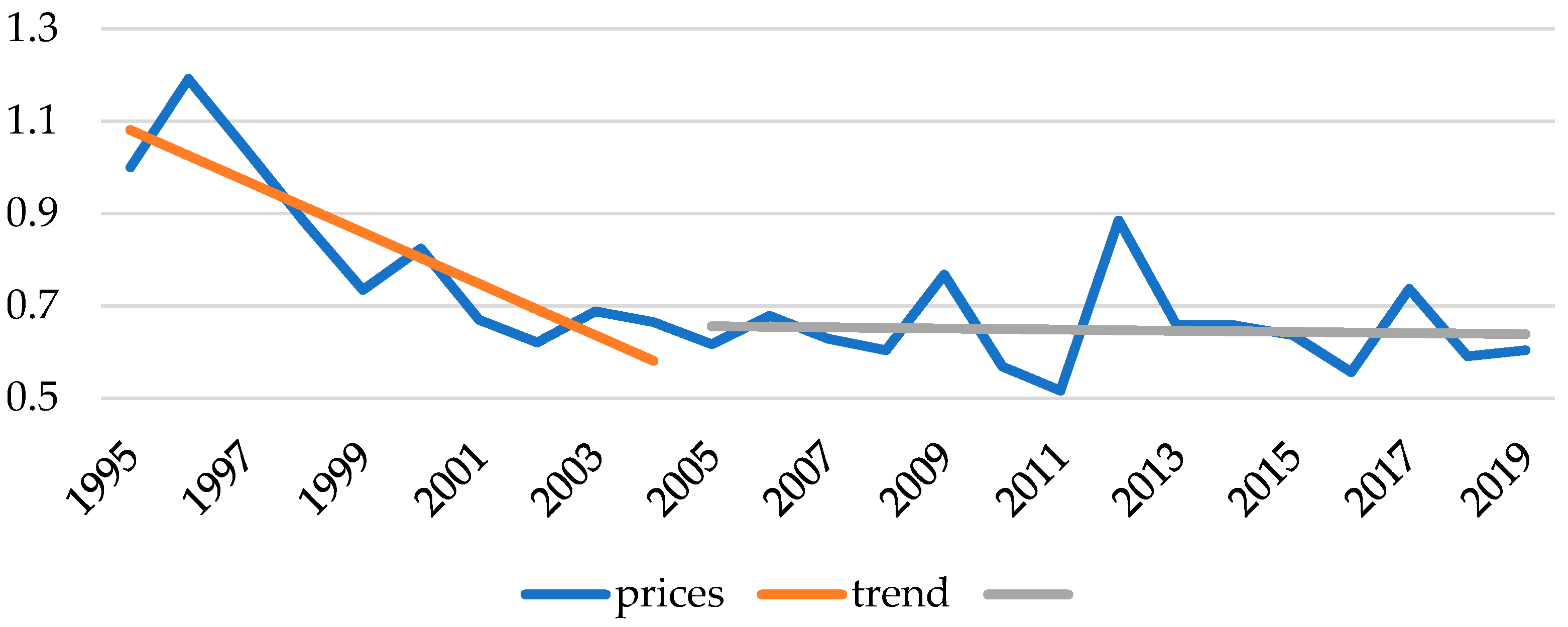

4.2. Changes in the Level of Agricultural Commodity Prices and Food Prices before and after Poland’s Accession to the EU

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Chavas, J.-P.; Mehta, A. Price Dynamics in a Vertical Sector: The Case of Butter. Am. J. Agric. Econ. 2004, 86, 1078–1093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, J.; von Cramon-Taubadel, S. Asymmetric Price Transmission: A Survey. J. Agric. Econ. 2004, 55, 581–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamulczuk, M. Structural Breaks in Farm and Retail Prices of Beef Meat in Poland. Quant. Methods Econ. 2013, 14, 160–169. [Google Scholar]

- Kinnucan, H.W.; Zhang, D. Notes on farm-retail price transmission and marketing margin behavior. Agric. Econ. 2015, 46, 729–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLaren, A. Asymmetry in price transmission in agricultural markets. Rev. Dev. Econ. 2015, 19, 415–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam, M.J.; McKenzie, A.M.; Begum, I.A.; Buysse, J.; Wailes, E.J.; Van Huylenbroeck, G. Asymmetry Price Transmission in the Deregulated Rice Markets in Bangladesh: Asymmetric Error Correction Model. Agribusiness 2016, 32, 498–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kouyaté, C.; von Cramon-Taubadel, S. Distance and Border Effects on Price Transmission: A Meta-analysis. J. Agric. Econ. 2016, 67, 255–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deb, L.; Lee, Y.; Lee, S.H. Market Integration and Price Transmission in the Vertical Supply Chain of Rice: An Evidence from Bangladesh. Agriculture 2020, 10, 271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rembisz, W. Determining the Acceptable Price Level for Agri-Food Products and the Choice of the Processor. Probl. Agric. Econ. 2021, 368, 95–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lagi, M.; Bertrand, K.Z.; Bar-Yam, Y. The food crises and political instability in North Africa and the Middle East. 2011. Available online: https://arxiv.org/abs/1108.2455 (accessed on 5 January 2022).

- Anderson, K. Government trade restrictions and international price volatility. Glob. Food Secur. 2012, 1, 157–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Headey, D. Food Prices and Poverty Reduction in the Long Run; IFPRI Discussion Paper 1331; International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI): Washington, DC, USA, 2014; Available online: http://ebrary.ifpri.org/cdm/ref/collection/p15738coll2/id/128056 (accessed on 8 December 2021).

- Bellemare, M.F. Rising Food Prices, Food Price Volatility, and Social Unrest. Am. J. Agric. Econ. 2015, 97, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timmer, C.P. Food Security and Scarcity; University of Pennsylvania Press: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaetano, S.F.; Emilia, L.; Francesco, C.; Gianluca, N.; Antonio, S. Drivers of grain price volatility: A cursory critical review. Agric. Econ. 2018, 64, 347–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin-Shields, C.P.; Stojetz, W. Food security and conflict: Empirical challenges and future opportunities for research and policy making on food security and conflict. World Dev. 2019, 119, 150–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vu, T.N.; Ho, C.M.; Nguyen, T.C.; Vo, D.H. The Determinants of Risk Transmission between Oil and Agricultural Prices: An IPVAR Approach. Agriculture 2020, 10, 120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borsellino, V.; Schimmenti, E.; El Bilali, H. Agri-Food Markets towards Sustainable Patterns. Sustainability 2020, 12, 2193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gardner, B.L. The Farm-Retail Price Spread in a Competitive Food Industry. Am. J. Agric. Econ. 1975, 57, 399–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peltzman, S. Prices Rise Faster than They Fall. J. Political Econ. 2000, 108, 466–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dawe, D.; Morales-Opazo, C.; Balie, J.; Pierre, G. How much have domestic food prices increased in the new era of higher food prices? Glob. Food Secur. 2015, 5, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Short, C.; Barreiro-Hurle, J.; Balié, J. Policy or Markets? An Analysis of Price Incentives and Disincentives for Rice and Cotton in Selected African Countries. Can. J. Agric. Econ. /Rev. Can. D’agroeconomie 2014, 62, 441–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baquedano, F.G.; Liefert, W.M. Market integration and price transmission in consumer markets of developing countries. Food Policy 2014, 44, 103–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kusz, D. Level of investment expenditure versus changes in technical labour equipment and labour efficiency in agriculture in Poland. In Proceedings of the International Scientific Conference “Economic Sciences for Agribusiness and Rural Economy” No 1, Warsaw, Poland, 7–8 June 2018; pp. 315–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Takayama, T.; Judge, G.G. Spatial and Temporal Price and Allocation Models; North-Holland Publishing: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1971. [Google Scholar]

- Sexton, R.J. Imperfect Competition in Agricultural Markets and the Role of Cooperatives: A Spatial Analysis. Am. J. Agric. Econ. 1990, 72, 709–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kinnucan, H.; Forker, O. Asymmetry in farm-retail price transmission for major dairy products. Am. J. Agric. Econ. 1987, 69, 285–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyd, M.S.; Brorsen, B.W. Price asymmetry in the US pork marketing channel. Appl. Econ. Perspect. Policy 1988, 10, 103–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damania, R.; Yang, B.Z. Price Rigidity and Asymmetric Price Adjustment in a Repeated Oligopoly. J. Inst. Theor. Econ. (JITE)/Z. Für Die Gesamte Staatswiss. 1998, 154, 659–679. [Google Scholar]

- McCorriston, S.; Morgan, C.W.; Rayner, A.J. Price transmission: The interaction between market power and returns to scale. Eur. Rev. Agric. Econ. 2001, 28, 143–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sexton, R.J.; Lavoie, N. Food Processing and Distribution: An Industrial Organization Approach. In Handbook of Agricultural Economics; Gardner, B.L., Rausser, G.C., Eds.; North Holland: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2001; Volume 1, Part B, pp. 863–932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheldon, I.; Sperling, R. Estimating the Extent of Imperfect Competition in the Food Industry: What have we learned? J. Agric. Econ. 2003, 54, 89–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakucs, Z.; Fałkowski, J.; Fertő, I. Does market structure influence price transmission in the agro-food sector? A meta-analysis perspective. J. Agric. Econ. 2014, 65, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lloyd, T. Forty years of price transmission research in the food industry: Insights, challenges and prospects. J. Agric. Econ. 2017, 68, 3–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, S. Concentrated Market Power and Agricultural Trade. Ecofair Trade Dialogue Discussion Paper No. 1. 2006. Available online: https://www.iatp.org/sites/default/files/451_2_89014.pdf (accessed on 7 December 2021).

- Rogers, R.T.; Sexton, R.J. Assessing the Importance of Oligopsony Power in Agricultural Markets. Am. J. Agric. Econ. 1994, 76, 1143–1150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kusz, D. Significance of Public Funds in Investment Activity of Farms in Poland (on the Example of Podkarpacie). Probl. Agric. Econ. 2015, 345, 16–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barro, R. A Theory of monopolistic price adjustment. Rev. Econ. Stud. 1972, 39, 17–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, R.N. Search Costs, Lags and Prices at the Pump. Rev. Ind. Organ. 2002, 20, 33–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richards, T.J.; Gómez, M.I.; Lee, J. Pass-Through and Consumer Search: An Empirical Analysis. Am. J. Agric. Econ. 2014, 96, 1049–1069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buckle, R.A.; Carlson, J.A. Menu costs, firm size and price rigidity. Econ. Lett. 2000, 66, 59–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blinder, A.S. Inventories and Sticky Prices: More on the Microfoundations of Macroeconomics. Am. Econ. Rev. 1982, 72, 334–348. [Google Scholar]

- Reagan, P.B.; Weitzman, M.L. Asymmetries in Price and Quantity Adjustments by the competitive Firm. J. Econ. Theory 1982, 27, 410–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balke, N.S.; Brown, S.P.; Yucel, M.K. Crude oil and gasoline prices: An asymmetric relationship? Econ. Financ. Policy Rev. 1998, Q1, 2–11. [Google Scholar]

- Cui, T.H.; Raju, J.S.; Zhang, J.Z. A Price Discrimination Model of Trade Promotions. Mark. Sci. 2008, 27, 779–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antonioli, F.; Santeramo, F.G. On Policy Interventions and Vertical Price Transmission: The Italian Milk Supply Chain Case. J. Agric. Resour. Econ. 2021, Preprint. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bailey, D.; Brorsen, B.W. Price Asymmetry in Spatial Fed Cattle Markets. West. J. Agric. Econ. 1989, 14, 246–252. [Google Scholar]

- Busse, M.; Silva-Risso, J.; Zettelmeyer, F. $1000 Cash Back: The Pass-Through of Auto Manufacturer Promotions. Am. Econ. Rev. 2006, 96, 1253–1270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esposti, R.; Listorti, G. Agricultural price transmission across space and commodities during price bubbles. Agric. Econ. 2013, 44, 125–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Chavas, J.-P.; Etienne, X.L.; Li, C. Commodity price bubbles and macroeconomics: Evidence from the Chinese agricultural markets. Agric. Econ. 2017, 48, 755–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baffes, J.; Haniotis, T. Placing the recent commodity boom into perspective. In Food Prices and Rural Poverty; Aksoy, M.A., Hoekman, B., Eds.; Centre for Economic Policy Research and the World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2010; pp. 41–70. Available online: https://cepr.org/sites/default/files/geneva_reports/GenevaP212.pdf (accessed on 6 December 2021).

- Wright, B.D. International Grain Reserves and Other Instruments to Address Volatility in Grain Markets. World Bank Res. Obs. 2012, 27, 222–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conforti, P. Price Transmission in Selected Agricultural Markets; FAO Commodity and Trade Policy Research Working Paper Series No. 7; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2004; Available online: https://www.fao.org/3/j2730e/j2730e.pdf (accessed on 9 November 2021).

- Stigler, M. Commodity prices: Theoretical and empirical properties. In Safeguarding Food Security in Volatile Global Markets; Prakash, A., Ed.; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2011; pp. 25–41. Available online: https://www.fao.org/3/i2107e/i2107e00.htm (accessed on 12 November 2021).

- Dornbusch, R. Exchange Rates and Prices. Am. Econ. Rev. 1987, 77, 93–106. [Google Scholar]

- Papell, D.H. Exchange Rates and Prices: An Empirical Analysis. Int. Econ. Rev. 1994, 35, 397–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liefert, W.M.; Suresh, P. The Transmission of Exchange Rate Changes to Agricultural Prices; Economic Research Report 55942; United States Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service: Washington, DC, USA, 2009. Available online: https://www.ers.usda.gov/publications/pub-details/?pubid=46191 (accessed on 28 October 2021).

- Elleby, C.; Jensen, F. Food price transmission and economic development. J. Dev. Stud. 2019, 55, 1708–1725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldwin, R.E.; Venables, A.J. Regional economic integration. In Handbook of International Economics; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1995; Volume 3, pp. 1597–1644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambert, D.M.; Grant, J.H. Do regional trade agreements increase members’ agricultural trade? Am. J. Agric. Econ. 2008, 90, 765–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mundlak, Y.; Larson, D.F. On the Transmission of World Agricultural Prices. World Bank Econ. Rev. 1992, 6, 399–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fackler, P.L.; Goodwin, B.K. Spatial price analysis. In Handbook of Agricultural Economics; Gardner, B.L., Rausser, G.C., Eds.; Elsevier Science: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2001; Volume 1B, pp. 971–1024. [Google Scholar]

- Rapsomanikis, G.; Hallam, D.; Conforti, P. Market integration and price transmission in selected food and cash crop markets of developing countries: Review and applications. In Agricultural Commodity Markets and Trade. New Approaches to Analyzing Market Structure and Instability; Sarris, A., Hallam, D., Eds.; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations and Edward Elgar Publishing Limited: Cheltenham, UK; Northampton, MA, USA, 2006; pp. 187–217. [Google Scholar]

- Baffes, J.; Gardner, B. The transmission of world commodity prices to domestic markets under policy reforms in developing countries. J. Policy Reform 2003, 6, 159–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Germán, S.; Bardají, I.; Garrido, A. Evaluating price transmission between global agricultural markets and consumer food price indices in the European Union. Agric. Econ. 2016, 47, 59–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bukeviciute, L.; Dierx, A.; Ilzkovitz, F. The Functioning of the Food Supply Chain and Its Effect on Food Prices in the European Union. Occasional Papers No. 47. 2009. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/economy_finance/publications/pages/publication15234_en.pdf (accessed on 5 March 2022).

- Ferrucci, G.; Jiménez-Rodríguez, R.; Onorante, L. Food Price Pass-Through in the Euro Area. The Role of Asymmetries and Non-Linearities; ECB Working Paper, No. 1168; European Central Bank (ECB): Frankfurt, Germany, 2010; Available online: https://www.ecb.europa.eu/pub/pdf/scpwps/ecbwp1168.pdf (accessed on 5 March 2022).

- Lloyd, T.; McCorriston, S.; Morgan, W.; Zgovu, E. European retail food price inflation. EuroChoices 2013, 12, 37–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porqueddu, M.; Venditti, F. Do food commodity prices have asymmetric effects on euro-area inflation? Stud. Nonlinear Dyn. Econom. 2014, 18, 419–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spasojević, B.; Đukić, A.; Erić, O. Price stability of agricultural products in the European Union. Екoнoмика Пoљoпривреде 2018, 65, 1585–1598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lanfranchi, M.; Giannetto, C.; Rotondo, F.; Ivanova, M.; Dimitrova, V. Economic and social impacts of price volatility in the markets of agricultural products. Bulg. J. Agric. Sci. 2019, 25, 1063–1068. Available online: https://www.agrojournal.org/25/06-01.html (accessed on 12 November 2021).

- Bórawski, P.; Guth, M.; Parzonko, A.; Rokicki, T.; Perkowska, A.; Dunn, J. Price volatility of milk and dairy products in Poland after accession to the EU. Agric. Econ. 2021, 67, 111–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bórawski, P.; Guth, M.; Truszkowski, W.; Zuzek, D.; Beldycka-Bórawska, A.; Mickiewicz, B.; Szymańska, E.; Harper, J.K.; Dunn, J.W. Milk price changes in Poland in the context of the Common Agricultural Policy. Agric. Econ. Czech 2020, 66, 19–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pawlewicz, A. Change of Price Premiums Trend for Organic Food Products: The Example of the Polish Egg Market. Agriculture 2020, 10, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamulczuk, M.; Szajner, P. Sugar prices in Poland and their determinants. Probl. Agric. Econ. 2015, 345, 59–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roman, M. Spatial Integration of the Milk Market in Poland. Sustainability 2020, 12, 1471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Przygodzka, R.; Dziemianowicz, R.I. Transformation and its Impact on Structural Changes in Polish Agriculture. In Proceedings of the 104th EAAE-IAAE Seminar Agricultural Economics and Transition: “What Was Expected, What We Observed”, The Lessons Learned, Corvinus University of Budapest, Budapest, Hungary, 5–8 September 2007; pp. 1–13. Available online: https://ideas.repec.org/p/ags/eaa104/7836.html (accessed on 11 May 2021).

- Runowski, H.; Ziętara, W. Future role of agriculture in multifunctional development of rural areas. APSTRACT Appl. Stud. Agribus. Commer. 2011, 5, 29–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kusz, D. The Changes in Relations of Production Factors in Agriculture (The Case of Poland). Sci. Pap. Ser. Manag. Econ. Eng. Agric. Rural Dev. 2015, 15, 171–178. [Google Scholar]

- Frey, G.; Manera, M. Econometric models of asymmetric price transmission. J. Econ. Surv. 2007, 21, 349–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balaji Prabhu, B.V.; Dakshayini, M. Performance Analysis of the Regression and Time Series Predictive Models using Parallel Implementation for Agricultural Data. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2018, 132, 198–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, Y.; Wu, H. Prediction of corn price fluctuation based on multiple linear regression analysis model under big data. Neural Comput. Appl. 2020, 32, 16843–16855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wibowo, A.; Yasmina, I. Food Price Prediction Using Time Series Linear Ridge Regression with the Best Damping Factor. Adv. Sci. Technol. Eng. Syst. J. 2021, 6, 694–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qingqi, Z. Housing Price Prediction Based on Multiple Linear Regression. Sci. Program. 2021, 2021, 7678931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prais, S.J.; Winsten, C.B. Trend Estimators and Serial Correlation; Cowles Commission Discussion Paper, Stat. No. 383; University of Chicago: Chicago, IL, USA, 1954; pp. 1–27. [Google Scholar]

- Canjels, E.; Watson, M.W. Estimating Deterministic Trends in the Presence of Serially Correlated Errors. Rev. Econ. Stat. 1997, 79, 184–200. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/2951451 (accessed on 9 February 2020). [CrossRef]

- Fried, R.; Gather, U. Robust Trend Estimation for AR(1) Disturbances. Austrian J. Stat. 2005, 34, 139–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Draper, N.R.; Smith, H. Applied Regression Analysis; John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Orłowski, W.M. Trajectories of the economic transition in Central and Easten Europe. In Social and Economic Development in Central and Eastern Europe. Stability and Change after 1990; Gorzelak, G., Ed.; Routledge: Abingdon, NY, USA, 2020; pp. 11–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campos, N.F.; Coricelli, F.; Moretti, L. Economic Growth and Political Integration: Estimating the Benefits from Membership in the European Union Using the Synthetic Counterfactuals Method; Discussion Paper No. 8162; Institute for the Study of Labor: Bonn, Germany, 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kusz, D.; Gędek, S.; Ruda, M.; Zając, S. Endogenous determinants of investments in farms of selected countries of Central and Eastern Europe. Sci. Papers. Ser. Manag. Econ. Eng. Agric. Rural Dev. 2014, 14, 107–116. Available online: http://managementjournal.usamv.ro/pdf/vol_14/art16.pdf (accessed on 3 November 2021).

- Anderson, K. Agricultural price distortions: Trends and volatility, past, and prospective. Agric. Econ. 2013, 44, 163–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cochrane, W.W. Farm Prices: Myth and Reality; University of Minnesota Press: Minneapolis, MN, USA, 1958. [Google Scholar]

- Czyżewski, B.; Czyżewski, A.; Kryszak, Ł. The Market Treadmill against Sustainable Income of European Farmers: How the CAP Has Struggled with Cochrane’s Curse. Sustainability 2019, 11, 791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czyżewski, B. Political Rents of European Farmers in the Sustainable Development Paradigm. In International, National and Regional Perspective; PWN: Warsaw, Poland, 2016; Available online: https://depot.ceon.pl/handle/123456789/10332 (accessed on 4 November 2021).

- Baffes, J.; Dennis, A. Long-Term Drivers of Food Prices; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Riston, C. Agricultural Economics Principles and Policy; Westview: Denver, CO, USA, 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Czyżewski, B. Surplus distribution in Polish agribusiness. Folia Pomeranae Univ. Technol. Stetin. Oeconomica 2013, 73, 61–69. [Google Scholar]

| Product | bR | bP | SbR | SbP | t | t_kr | p-Value of the Difference Test |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wheat (Raw Material, Prices Obtained by Farmers) and Wheat-Based Food (Retail Prices) | |||||||

| Bread | −0.06413 | 0.065343 | 0.013427 | 0.02363 | −4.7638 | −1.8595 | 0.001 |

| Roll | 0.021559 | 0.013427 | 0.01026 | −5.0708 | −1.8595 | 0.000 | |

| Flour | −0.05468 | 0.013427 | 0.011267 | −0.5388 | −1.8595 | 0.302 | |

| Pasta | 0.022795 | 0.013427 | 0.004736 | −6.1052 | −1.8595 | 0.000 | |

| Beef (Raw Material, Prices Obtained by Farmers) and Roast Beef (Food, Retail Prices) | |||||||

| Roast beef | −0.03686 | 0 | 0.012598 | 0 | −2.9256 | −1.8595 | 0.010 |

| Milk (Raw Material, Prices Obtained by Farmers) and Dairy Products (Retail Prices) | |||||||

| Butter | −0.01129 | −0.02165 | 0.008496 | 0.005643 | 1.0158 | −1.8595 | 0.830 |

| Milk (retail prices) | −0.03608 | 0.005643 | 0.009197 | 2.2975 | −1.8595 | 0.975 | |

| Cottage cheese | −0.02285 | 0.005643 | 0.006242 | 1.3746 | −1.8595 | 0.897 | |

| Cheeses | −0.02399 | 0.005643 | 0.004724 | 1.7263 | −1.8595 | 0.939 | |

| Eggs (Raw Material, Prices Obtained by Farmers) and Hen Eggs, Fresh (Retail Prices) | |||||||

| Eggs | −0.05524 | −0.03487 | 0.010959 | 0.012442 | −1.2287 | −1.8595 | 0.127 |

| Poultry (Raw Material, Prices Obtained by Farmers) and Poultry Meat (Retail Prices) | |||||||

| Poultry | −0.05345 | −0.05446 | 0.013851 | 0.01133 | 0.0565 | −1.8595 | 0.522 |

| Pork (Raw Material, Prices Obtained by Farmers) and Pork Products (Retail Prices) | |||||||

| Boneless meat | −0.03713 | −0.05341 | 0.009628 | 0.008117 | 1.2929 | −1.8595 | 0.884 |

| Pork loin b.k | −0.05342 | 0.009628 | 0.008117 | 1.2929 | −1.8595 | 0.884 | |

| Pork frankfurters | −0.02758 | 0.009628 | 0.004685 | −0.8919 | −1.8595 | 0.199 | |

| Ham | −0.03646 | 0.009628 | 0.007842 | −0.0538 | −1.8595 | 0.479 | |

| Sausage | −0.02321 | 0.009628 | 0.005363 | −1.2629 | −1.8595 | 0.121 | |

| Raw Material (Prices Received by the Farmer) | Food Product (Retail Prices) | Type of Trend 1995–2004 | Type of Trend 2005–2019 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Raw Material | Product | Conclusion | Raw Material | Product | Conclusion | ||

| Wheat | Bread | decreasing | increasing | ** | none | increasing | ** |

| Roll | decreasing | increasing | ** | none | none | ||

| Flour | decreasing | decreasing | none | increasing | ** | ||

| Pasta | decreasing | increasing | ** | none | none | ||

| Beef meat | Roast beef | decreasing | none | ** | Increasing | increasing | ** |

| Cow’s milk | Butter | decreasing | decreasing | none | increasing | ** | |

| Milk | decreasing | decreasing | none | increasing | irrelevant difference | ||

| Cottage cheese | decreasing | decreasing | none | increasing | ** | ||

| Cheeses | decreasing | decreasing | none | none | |||

| Eggs | Eggs | decreasing | decreasing | none | increasing | ** | |

| Livestock for slaughter-poultry | Poultry | decreasing | decreasing | none | none | ||

| Pigs | Boneless meat | decreasing | decreasing | none | none | ||

| Pork loin b.k | decreasing | decreasing | none | none | |||

| Pork frankfurters | decreasing | decreasing | none | increasing | ** | ||

| Ham | decreasing | decreasing | none | none | |||

| Sausage | decreasing | decreasing | none | none | |||

| Product | bR | bP | SbR | SbP | t | t_kr | p-Value of the Difference Test |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wheat (Raw Material, Prices Obtained by Farmers) and Wheat-Based Food (Retail Prices) | |||||||

| Bread | 0 | 0.046465 | 0 | 0.010198 | −4.5563 | −1.7709 | 0.000269 |

| Roll | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Flour | 0.016686 | 0 | 0.003219 | −5.1838 | −1.7709 | 0.001 | |

| Pasta | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Beef (Raw Material, Prices Obtained by Farmers) and Roast Beef (Food, Retail Prices) | |||||||

| Roast beef | 0.017526 | 0.028722 | 0.005353 | 0.003852 | −1.6976 | −1.3501 | 0.056688 |

| Milk (Raw Material, Prices Obtained by Farmers) and Dairy Products (Retail Prices) | |||||||

| Butter | 0 | 0.031862 | 0 | 0.009456 | −3.3693 | −1.7709 | 0.002515 |

| Milk (retail prices) | −0.00726 | 0 | 0.001608 | 4.5184 | −1.7709 | 0.999711 | |

| Cottage cheese | 0.005943 | 0 | 0.002848 | −2.0867 | −1.7709 | 0.028585 | |

| Cheeses | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Eggs (Raw Material, Prices Obtained by Farmers) and Hen Eggs, Fresh (Retail Prices) | |||||||

| Eggs | 0 | 0.02189 | 0.010959 | 0.00439 | −1.8542 | −1.7709 | 0.04326 |

| Poultry (Raw Material, Prices Obtained by Farmers) and Poultry Meat (Retail Prices) | |||||||

| Poultry | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Pork (Raw Material, Prices Obtained by Farmers) and Pork Products (Retail Prices) | |||||||

| Boneless meat | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Pork loin b.k | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Pork frankfurters | 0.033534 | 0 | 0.001363 | −24.5984 | −1.7709 | 0.0000 | |

| Ham | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Sausage | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kusz, D.; Kusz, B.; Hydzik, P. Changes in the Price of Food and Agricultural Raw Materials in Poland in the Context of the European Union Accession. Sustainability 2022, 14, 4582. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14084582

Kusz D, Kusz B, Hydzik P. Changes in the Price of Food and Agricultural Raw Materials in Poland in the Context of the European Union Accession. Sustainability. 2022; 14(8):4582. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14084582

Chicago/Turabian StyleKusz, Dariusz, Bożena Kusz, and Paweł Hydzik. 2022. "Changes in the Price of Food and Agricultural Raw Materials in Poland in the Context of the European Union Accession" Sustainability 14, no. 8: 4582. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14084582

APA StyleKusz, D., Kusz, B., & Hydzik, P. (2022). Changes in the Price of Food and Agricultural Raw Materials in Poland in the Context of the European Union Accession. Sustainability, 14(8), 4582. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14084582