The Impact of Knowledge Management Capabilities on Innovation Performance from Dynamic Capabilities Perspective: Moderating the Role of Environmental Dynamism

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Foundations and Literature Review

2.1. Knowledge Management from a Dynamic Capability Perspective

2.2. Innovation Performance

2.3. Environmental Dynamism

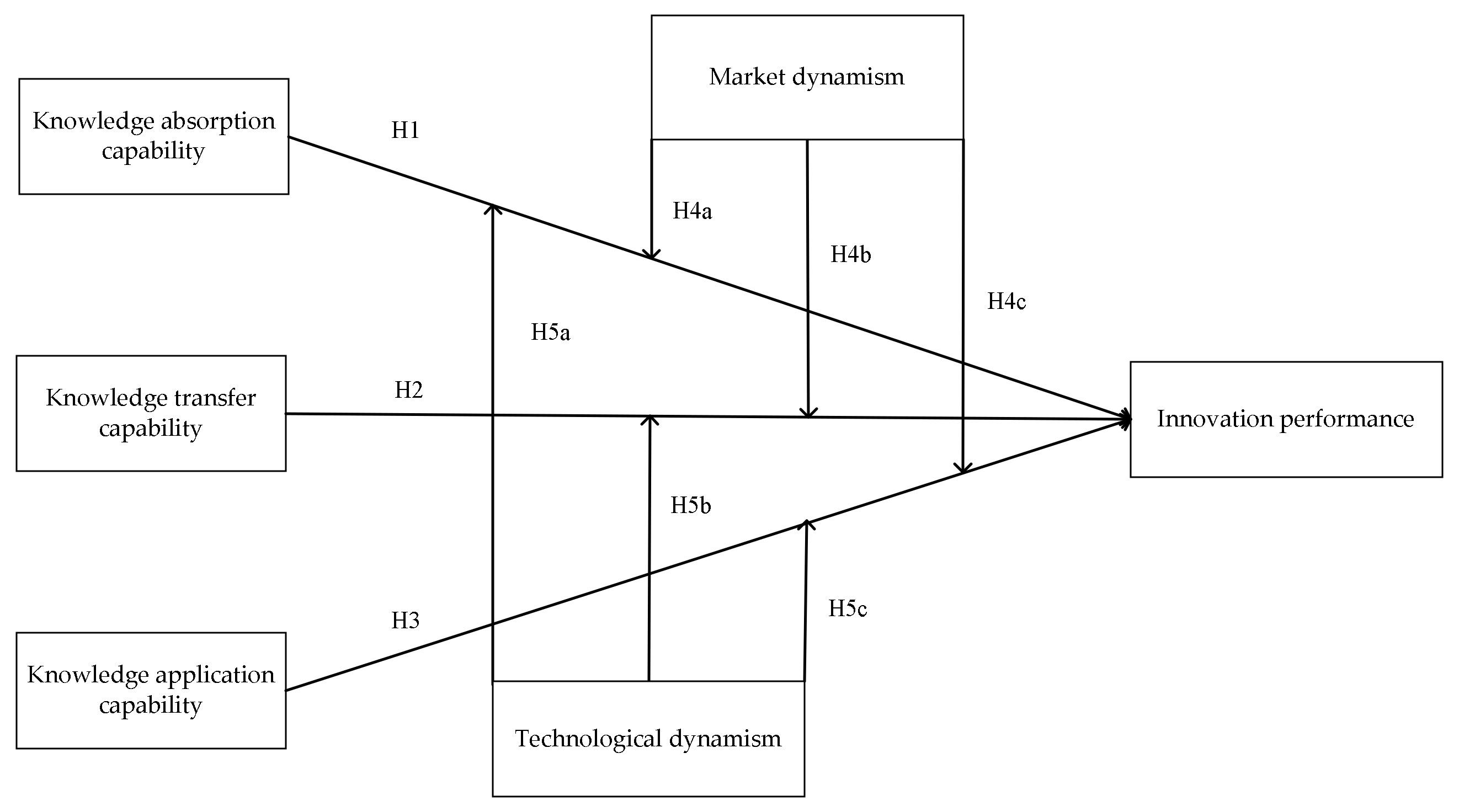

3. Hypothesis Development

3.1. Knowledge Absorption Capability and Innovation Performance

3.2. Knowledge Transfer Capability and Innovation Performance

3.3. Knowledge Application Capability and Innovation Performance

3.4. The Moderating Effects of Environmental Dynamism

4. Methods

4.1. Research Approach

4.2. Questionnaire Development

4.3. Sample and Procedures

4.4. Variables and Measures

4.4.1. Dynamic Knowledge Management Capabilities

4.4.2. Innovative Performance

4.4.3. Environmental Dynamism

4.4.4. Control Variables

4.5. Demographic Analysis

5. Results

5.1. Reliability and Validity

5.2. Common Method Bias

5.3. Descriptive Statistics and Correlation Analysis

5.4. Testing of Hypotheses

5.4.1. Main Effect Analysis

5.4.2. Moderating Effect Analysis

6. Discussions

7. Conclusions

7.1. Theoretical Contributions

7.2. Practical Implications

7.3. Limitations and Future Research Directions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Main Survey Questions

- Our company has a dedicated knowledge learning and information sharing platform.

- Our company structure is well designed to facilitate the absorption and exchange of knowledge.

- Employees in our company are encouraged to absorb and learn about the industry in order to promote knowledge innovation.

- Our company obtains information from external sources (competitors, partners, customers, experts, consulting and training organizations, government departments, etc.).

- Our company keeps track of changes in market demand for new products or services and communicates these to our employees in a timely manner.

- Our company invites external experts to train employees and learn from their experience and skills.

- Our company attaches importance to staff learning and training, as well as the promotion and application of training content and other activities.

- Our company encourages a mentor-apprentice approach to training to enable the transfer of knowledge such as personal experience and work skills.

- Our company regularly classifies and organizes customer data and market information in order to obtain new findings to guide marketing and product development.

- Our company regularly analyzes and discusses the existing technical accumulation to discover new possibilities for technical applications or innovations.

- Our company regularly collates personal experience and knowledge generated in the workplace and disseminates it internally.

- Our company can respond effectively to competitive threats and market opportunities by harnessing the power of knowledge from within and outside the organization.

- Our company can make effective use of externally acquired technical and market information in the development of its products or services.

- Our company can ensure that knowledge is appropriately deployed and used across different departments.

- The assignments are matched to the knowledge and skills of individual employees.

- Our company can take advantage of new technological opportunities to develop new products or services.

- Our company regularly adapts and improves existing technologies in line with new knowledge.

- The customer preferences and tendencies change rapidly in the markets.

- The existing customers always tend to seek new products and services.

- The extent of change in the company's market position is significant.

- The rapid pace of change in relevant technologies within the company’s business areas.

- It is difficult to predict the dominant technology in the company’s current business area five years from now.

- Technological changes in the industry provide additional opportunities for the company’s business development.

- Compared to peers, our company has introduced more new ways of production operations.

- Compared to peers, our company’s input-output efficiency in new product development is above average.

- Compared to peers, our company has first-class technology and processes.

- Compared to peers, our company is often the first in the industry to introduce new technologies/products/services.

- Compared to peers, technical content of our new products is above average.

- Compared to peers, our product innovations and enhancements often achieve better market response.

References

- Migdadi, M.M.; Zaid, M.K.A.; Yousif, M.; Almestarihi, R.D.; Khalil, A.H. An empirical examination of knowledge management processes and market orientation, innovation capability, and organisational performance: Insights from Jordan. J. Inf. Knowl. Manag. 2017, 16, 1750002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhining, W.; Nianxin, W. Knowledge sharing, innovation and firm performance. Expert Syst. Appl. 2012, 39, 8899–8908. [Google Scholar]

- Cabrilo, S.; Dahms, S. How strategic knowledge management drives intellectual capital to superior innovation and market performance. J. Knowl. Manag. 2018, 22, 621–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alavi, M.; Tiwana, A. Knowledge integration in virtual teams: The potential role of KMS. J. Am. Soc. Inf. Sci. Technol. 2002, 53, 1029–1037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexandru, V.A.; Bolisani, E.; Andrei, A.G.; Gabriel, C.N.; Aurora, M.M.; Paiola, M.; Scarso, E.; Vatamanescu, E.M.; Zieba, M. Knowledge management approaches of small and medium-sized firms: A cluster analysis. Kybernetes 2020, 49, 73–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Changfeng, W.; Qiying, H. Knowledge sharing in supply chain networks: Effects of collaborative innovation activities and capability on innovation performance. Technovation 2020, 94, 102010. [Google Scholar]

- Tortoriello, M.; Reagans, R.; McEvily, B. Bridging the knowledge gap: The influence of strong ties, network cohesion, and network range on the transfer of knowledge between organizational units. Organ. Sci. 2012, 23, 1024–1039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dezi, L.; Ferraris, A.; Papa, A.; Vrontis, D. The role of external embeddedness and knowledge management as antecedents of ambidexterity and performances in Italian SMEs. IEEE Trans. Eng. Manag. 2021, 68, 360–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, A.S.; Griffith, D.A.; Cavusgil, S.T. The influence of competitive intensity and market dynamism on knowledge management capabilities of multinational corporation subsidiaries. J. Int. Mark. 2005, 13, 32–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soto Acosta, P.; Popa, S.; Martinez Conesa, I. Information technology, knowledge management and environmental dynamism as drivers of innovation ambidexterity: A study in SMEs. J. Knowl. Manag. 2018, 22, 931–948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taghizadeh, S.K.; Karini, A.; Nadarajah, G.; Nikbin, D. Knowledge management capability, environmental dynamism and innovation strategy in Malaysian firms. Manag. Decis. 2021, 59, 1386–1405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.K.; Gupta, S.; Busso, D.; Kamboj, S. Top management knowledge value, knowledge sharing practices, open innovation and organizational performance. J. Bus. Res. 2021, 128, 788–798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Attia, A.; Eldin, I.E. Organizational learning, knowledge management capability and supply chain management practices in the Saudi food industry. J. Knowl. Manag. 2018, 22, 1217–1242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamad, A.A.; Ramayah, T.; May Chiun, L. Sustainable knowledge management and firm innovativeness: The contingent role of innovative culture. Sustainability 2020, 12, 6910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teece, D.J. Dynamic capabilities: Routines versus entrepreneurial action. J. Manag. Stud. 2012, 49, 1395–1401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verona, G.; Ravasi, D. Unbundling dynamic capabilities: An exploratory study of continuous product innovation. Ind. Corp. Change 2003, 12, 577–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Nielsen, A.P. Understanding dynamic capabilities through knowledge management. J. Knowl. Manag. 2006, 10, 59–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zollo, M.; Winter, S.G. Deliberate learning and the evolution of dynamic capabilities. Organ. Sci. 2002, 13, 339–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hilliard, R.; Goldstein, D. Identifying and measuring dynamic capability using search routines. Strateg. Organ. 2019, 17, 210–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denford, J.S. Building knowledge: Developing a knowledge-based dynamic capabilities typology. J. Knowl. Manag. 2013, 17, 175–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suli, Z.; Wei, Z.; Xiaobo, W.; Jian, W. Knowledge-based dynamic capabilities and innovation in networked environments. J. Knowl. Manag. 2011, 15, 1035–1051. [Google Scholar]

- Kindstrom, D.; Kowalkowski, C.; Sandberg, E. Enabling service innovation: A dynamic capabilities approach. J. Bus. Res. 2013, 66, 1063–1073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Santoro, G.; Bresciani, S.; Papa, A. Collaborative modes with cultural and creative industries and innovation performance: The moderating role of heterogeneous sources of knowledge and absorptive capacity. Technovation 2020, 92–93, 102040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gold, A.H.; Malhotra, A.; Segars, A.H. Knowledge management: An organizational capabilities perspective. J. Manag. Inf. Syst. 2001, 18, 185–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nonaka, I. A dynamic theory of organizational knowledge creation. Organ. Sci. 1994, 5, 14–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Soto Acosta, P.; Popa, S.; Palacios Marqués, D. E-business, organizational innovation and firm performance in manufacturing SMEs: An empirical study in Spain. Technol. Econ. Dev. Econ. 2016, 22, 885–904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Laursen, K.; Salter, A. Open for innovation: The role of openness in explaining innovation performance among UK manufacturing firms. Strateg. Manag. J. 2006, 27, 131–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodale, J.C.; Kuratko, D.F.; Hornsby, J.S.; Covin, J.G. Operations management and corporate entrepreneurship: The moderating effect of operations control on the antecedents of corporate entrepreneurial activity in relation to innovation performance. J. Oper. Manag. 2011, 29, 116–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papa, A.; Dezi, L.; Gregori, G.L.; Mueller, J.; Miglietta, N. Improving innovation performance through knowledge acquisition: The moderating role of employee retention and human resource management practices. J. Knowl. Manag. 2020, 24, 589–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hameed, W.U.; Nisar, Q.A.; Wu, H.C. Relationships between external knowledge, internal innovation, firms’ open innovation performance, service innovation and business performance in the Pakistani hotel industry. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2021, 92, 102745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexiev, A.S.; Volberda, H.W.; Van den Bosch, F.A.J. Interorganizational collaboration and firm innovativeness: Unpacking the role of the organizational environment. J. Bus. Res. 2016, 69, 974–984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, D.; Friesen, P.H. Strategy-making and environment: The third link. Strateg. Manag. J. 1983, 4, 221–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teece, D.J. Business models and dynamic capabilities. Long Range Plan. 2018, 51, 40–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lichtenthaler, U.; Lichtenthaler, E. A capability-based framework for open innovation: Complementing absorptive capacity. J. Manag. Stud. 2009, 46, 1315–1338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popa, S.; Soto Acosta, P.; Martinez Conesa, I. Antecedents, moderators, and outcomes of innovation climate and open innovation: An empirical study in SMEs. Technol. Forecast. Soc. 2017, 118, 134–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, K.Z.; Li, C.B. How knowledge affects radical innovation: Knowledge base, market knowledge acquisition, and internal knowledge sharing. Strateg. Manag. J. 2012, 33, 1090–1102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scuotto, V.; Santoro, G.; Bresciani, S.; Del Giudice, M. Shifting intra- and inter-organizational innovation processes towards digital business: An empirical analysis of SMEs. Creat. Innov. Manag. 2017, 26, 247–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trantopoulos, K.; von Krogh, G.; Wallin, M.W.; Woerter, M. External knowledge and information technology: Implications for process innovation performance. MIS Q. 2017, 41, 287–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- George, G.; McGahan, A.M.; Prabhu, J. Innovation for inclusive growth: Towards a theoretical framework and a research agenda. J. Manag. Stud. 2012, 49, 661–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vendrell Herrero, F.; Bustinza, O.F.; Opazo Basaez, M. Information technologies and product-service innovation: The moderating role of service R&D team structure. J. Bus. Res. 2021, 128, 673–687. [Google Scholar]

- Scuotto, V.; Beatrice, O.; Valentina, C.; Nicotra, M.; Di Gioia, L.; Briamonte, M.F. Uncovering the micro-foundations of knowledge sharing in open innovation partnerships: An intention-based perspective of technology transfer. Technol. Forecast. Soc. 2020, 152, 119906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rong, L.; YiFei, D.; HongJuan, T.; Boadu, F.; Min, X. MNEs’ subsidiary HRM practices and firm innovative performance: A tacit knowledge approach. Sustainability 2019, 11, 1388. [Google Scholar]

- Shiaw Tong, H.; May Chiun, L.; Mohamad Kadim, S.; Abang Azlan, M.; Zaidi Bin, R. Knowledge Management process, entrepreneurial orientation, and performance in SMEs: Evidence from an emerging economy. Sustainability 2021, 13, 9791. [Google Scholar]

- Shujahat, M.; Sousa, M.J.; Hussain, S.; Nawaz, F.; Wang, M.; Umer, M. Translating the impact of knowledge management processes into knowledge-based innovation: The neglected and mediating role of knowledge-worker productivity. J. Bus. Res. 2019, 94, 442–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moorman, C.; Miner, A.S. Organizational improvisation and organizational memory. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1998, 23, 698–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lina, M.; Jinghua, L.; Changwei, G. Integrator’s coordination on technological innovation performance in China: The dual moderating role of environmental dynamism. Sustainability 2020, 12, 308. [Google Scholar]

- Perez Luno, A.; Gopalakrishnan, S.; Valle Cabrera, R. Innovation and performance: The role of environmental dynamism on the success of innovation choices. IEEE Trans. Eng. Manag. 2014, 61, 499–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleming, L. Recombinant uncertainty in technological search. Manag. Sci. 2001, 47, 117–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogbeibu, S.; Emelifeonwu, J.; Senadjki, A.; Gaskin, J.; Kaivooja, J. Technological turbulence and greening of team creativity, product innovation, and human resource management: Implications for sustainability. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 244, 118703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, K.; Hsieh, M.; Hultink, E.J. External technology acquisition and product innovativeness: The moderating roles of R&D investment and configurational context. J. Eng. Technol. Manag. 2011, 28, 184–200. [Google Scholar]

- Kohli, A.K.; Jaworski, B.J. Market orientation: The construct, research propositions, and managerial implications. J. Mark. 1990, 54, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lane, P.J.; Koka, B.R.; Pathak, S. The reification of absorptive capacity: A critical review and rejuvenation of the construct. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2006, 31, 833–863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahra, S.A.; Bogner, W.C. Technology strategy and software new ventures’ performance: Exploring the moderating effect of the competitive environment. J. Bus. Ventur. 2000, 15, 135–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gemünden, H.G.; Ritter, T.; Heydebreck, P. Network configuration and innovation success: An empirical analysis in German high-tech industries. Int. J. Res. Mark. 1996, 13, 449–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jansen, J.J.; Van Den Bosch, F.A.; Volberda, H.W. Exploratory innovation, exploitative innovation, and performance: Effects of organizational antecedents and environmental moderators. Manag. Sci. 2006, 52, 1661–1674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Martínez-Pérez, Á.; García-Villaverde, P.M.; Elche, D. The mediating effect of ambidextrous knowledge strategy between social capital and innovation of cultural tourism clusters firms. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2016, 28, 1484–1507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez-Conesa, I.; Soto-Acosta, P.; Carayannis, E.G. On the path towards open innovation: Assessing the role of knowledge management capability and environmental dynamism in SMEs. J. Knowl. Manag. 2017, 21, 553–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yiying, C.; Hughes, M.; Hotho, S. Internal and external antecedents of SMEs’ innovation ambidexterity outcomes. Manag. Decis. 2011, 49, 1658–1676. [Google Scholar]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Podsakoff, N.P. Sources of method bias in social science research and recommendations on how to control it. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2012, 63, 539–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hair, J.F., Jr.; Sarstedt, M.; Hopkins, L.; Kuppelwieser, V.G. Partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM): An emerging tool in business research. Eur. Bus. Rev. 2014, 24, 106–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, K.; Kim, E.; Jeong, E. Structural Relationship and Influence between Open Innovation Capacities and Performances. Sustainability 2018, 10, 2787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Thomas, A.; Paul, J. Knowledge transfer and innovation through university-industry partnership: An integrated theoretical view. Knowl. Manag. Res. Pract. 2019, 17, 436–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marsh, S.J.; Stock, G.N. Building dynamic capabilities in new product development through intertemporal integration. J. Prod. Innov. Manag. 2003, 20, 136–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigo-Alarcón, J.; García-Villaverde, P.M.; Parra-Requena, G.; Ruiz-Ortega, M.J. Innovativeness in the context of technological and market dynamism: The conflicting effects of network density. J. Organ. Change Manag. 2017, 30, 548–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atuahene Gima, K.; Li, H.Y.; de Luca, L.M. The contingent value of marketing strategy innovativeness for product development performance in Chinese new technology ventures. Ind. Market. Manag. 2006, 35, 359–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbas, J.; Kumari, K. Examining the relationship between total quality management and knowledge management and their impact on organizational performance: A dimensional analysis. Econ. Adm. Sci. 2021. ahead of print. [Google Scholar]

- Seo, E.H.; Kim, C.Y.; Kim, K. A study on the mechanisms linking environmental dynamism to innovation performance. Sustainability 2020, 12, 9999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taghizadeh, S.K.; Nikbin, D.; Alam, M.M.D.; Rahman, S.A.; Nadarajah, G. Technological capabilities, open innovation and perceived operational performance in SMEs: The moderating role of environmental dynamism. J. Knowl. Manag. 2021, 25, 1486–1507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Characteristics | Categories | Frequency (N) | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Industry | Advanced Manufacturing | 32 | 12.65% |

| Electronics | 57 | 22.53% | |

| IT | 73 | 28.85% | |

| Communications | 27 | 10.67% | |

| Biomedicine | 38 | 15.02% | |

| New Materials | 26 | 10.28% | |

| Ownership | SOEs | 62 | 24.51% |

| PEs | 107 | 42.29% | |

| FIEs | 60 | 23.72% | |

| Other | 24 | 9.48% | |

| Firm Age (Years) | 3 | 65 | 25.69% |

| 3–5 | 106 | 41.90% | |

| 5–10 | 52 | 20.55% | |

| >10 | 30 | 11.86% | |

| Firm size (Number of employees) | <100 | 33 | 13.04% |

| 100–300 | 105 | 41.51% | |

| 300–500 | 65 | 25.69% | |

| >500 | 50 | 19.76% | |

| Total | 253 | 100 | |

| Variables | Dimensions | Item Code | Loading | Cronbach’s Alpha | CR | AVE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dynamic Knowledge Management Capabilities | Knowledge Absorption Capability | KA1 | 0.816 | 0.872 | 0.892 | 0.509 |

| KA2 | 0.711 | |||||

| KA3 | 0.748 | |||||

| KA4 | 0.855 | |||||

| KA5 | 0.747 | |||||

| KA6 | 0.679 | |||||

| Knowledge Transfer Capability | KT1 | 0.645 | 0.800 | 0.859 | 0.552 | |

| KT2 | 0.798 | |||||

| KT3 | 0.746 | |||||

| KT4 | 0.832 | |||||

| KT5 | 0.677 | |||||

| Knowledge Application Capability | KP1 | 0.850 | 0.832 | 0.895 | 0.550 | |

| KP2 | 0.683 | |||||

| KP3 | 0.764 | |||||

| KP4 | 0.752 | |||||

| KP5 | 0.839 | |||||

| KP6 | 0.697 | |||||

| Environmental Dynamism | Market Dynamism | MD1 | 0.687 | 0.825 | 0.825 | 0.703 |

| MD2 | 0.764 | |||||

| MD3 | 0.886 | |||||

| Technological Dynamism | TD1 | 0.798 | 0.811 | 0.809 | 0.603 | |

| TD2 | 0.682 | |||||

| TD3 | 0.816 | |||||

| Innovation Performance | IP1 | 0.785 | 0.899 | 0.910 | 0.628 | |

| IP2 | 0.805 | |||||

| IP3 | 0.747 | |||||

| IP4 | 0.796 | |||||

| IP5 | 0.675 | |||||

| IP6 | 0.821 | |||||

| Variables | Mean | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Knowledge Absorption Capability | 3.264 | 0.636 | 0.714 | |||||

| 2. Knowledge Transfer Capability | 3.442 | 0.666 | 0.451 ** | 0.743 | ||||

| 3. Knowledge Application Capability | 3.342 | 0.611 | 0.704 ** | 0.611 ** | 0.742 | |||

| 4. Market Dynamism | 3.464 | 0.755 | 0.469 ** | 0.151 * | 0.434 ** | 0.838 | ||

| 5. Technological Dynamism | 3.481 | 0.752 | 0.586 ** | 0.282 ** | 0.613 ** | 0.718 ** | 0.776 | |

| 6. Innovation Performance | 3.206 | 0.693 | 0.633 ** | 0.502 ** | 0.686 ** | 0.478 ** | 0.570 ** | 0.793 |

| Variables | Innovation Performance | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | |

| Industry | −0.105 | −0.046 | −0.038 | −0.030 |

| Firm Type | 0.015 | −0.003 | 0.014 | −0.030 |

| Firm Age | 0.265 *** | 0.054 | 0.035 | −0.013 |

| Firm Size | −0.003 | 0.173 * | 0.124 * | 0.066 |

| Knowledge Absorption Capability (K1) | 0.239 *** | 0.218 *** | 0.106 * | |

| Knowledge Transfer Capability (K2) | 0.339 *** | 0.183 * | ||

| Knowledge Application Capability (K3) | 0.546 *** | |||

| R2 | 0.074 | 0.207 | 0.365 | 0.637 |

| Adjusted R2 | 0.074 | 0.133 | 0.158 | 0.272 |

| F-value | 4.978 *** | 49.766 *** | 37.671 *** | 31.398 *** |

| Variables | Innovation Performance | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 5 | Model 6 | Model 7 | Model 8 | Model 9 | |

| Industry | 0.006 | 0.006 | −0.005 | −0.005 | −0.008 |

| Firm Type | −0.045 | −0.060 * | −0.029 | −0.033 | −0.037 |

| Firm Age | 0.012 | 0.008 | 0.001 | −0.011 | −0.012 |

| Firm Size | 0.069 * | 0.057 | 0.043 | 0.076 * | 0.063 |

| K1 | 0.121 * | 0.105 * | 0.095 * | 0.088 * | 0.076 * |

| K2 | 0.130 * | 0.132 ** | 0.119 * | 0.104 * | 0.096 * |

| K3 | 0.494 *** | 0.510 *** | 0.434 *** | 0.475 *** | 0.337 *** |

| Market Dynamism (MD) | 0.189 *** | 0.086 * | |||

| Technological Dynamism (TD) | 0.313 *** | 0.307 *** | 0.294 *** | ||

| MD × K1 | 0.087 | 0.071 | |||

| MD × K2 | 0.168 * | 0.119 * | |||

| MD × K3 | −0.186 * | −0.092 * | |||

| TD × K1 | 0.109 * | 0.080 * | |||

| TD × K2 | 0.122 * | 0.146 * | |||

| TD × K3 | −0.145 ** | −0.102 * | |||

| R2 | 0.658 | 0.672 | 0.690 | 0.701 | 0.703 |

| Adjusted R2 | 0.021 | 0.035 | 0.053 | 0.064 | 0.066 |

| F | 58.704 *** | 44.797 *** | 67.946 *** | 51.255 *** | 37.350 *** |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Feng, L.; Zhao, Z.; Wang, J.; Zhang, K. The Impact of Knowledge Management Capabilities on Innovation Performance from Dynamic Capabilities Perspective: Moderating the Role of Environmental Dynamism. Sustainability 2022, 14, 4577. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14084577

Feng L, Zhao Z, Wang J, Zhang K. The Impact of Knowledge Management Capabilities on Innovation Performance from Dynamic Capabilities Perspective: Moderating the Role of Environmental Dynamism. Sustainability. 2022; 14(8):4577. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14084577

Chicago/Turabian StyleFeng, Lijie, Zhenzhen Zhao, Jinfeng Wang, and Ke Zhang. 2022. "The Impact of Knowledge Management Capabilities on Innovation Performance from Dynamic Capabilities Perspective: Moderating the Role of Environmental Dynamism" Sustainability 14, no. 8: 4577. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14084577

APA StyleFeng, L., Zhao, Z., Wang, J., & Zhang, K. (2022). The Impact of Knowledge Management Capabilities on Innovation Performance from Dynamic Capabilities Perspective: Moderating the Role of Environmental Dynamism. Sustainability, 14(8), 4577. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14084577