Abstract

Increasingly, business-to-consumer companies engage in corporate social advocacy (CSA) to respond to growing pressures from stakeholders. CSA studies are quickly accumulating, yet in-depth explanations of when and why the public expect companies to take a stance (sometimes even action) on controversial issues remain scarce. To fill these gaps, we unpack how Generation Z audiences expect companies to act on public agendas and their reasoning process through a mixed-method analysis of an exploratory survey (N = 388) conducted at a public university. The results show major changes in CSA expectations and illuminate the reasoning behind them. The results highlight a critical need to further understand CSA from audience perceptions and inform message design and testing guided by audience-centric models.

1. Introduction

The public increasingly demands corporations to take a stance on hot button issues (e.g., racial injustice or climate change) that reflect the public agenda for motivating societal change [1]. A recent public poll found that 68% of consumers expected prominent brands to speak up on controversial socio-political issues that matter to their generation and align with their values [2]. One recent example is the call for a boycott of Coca-Cola and Delta for their (in)action regarding the new voting laws in Georgia [3]. Researchers describe corporations’ responses and positions to these issues as corporate social responsibility (CSR), corporate social advocacy (CSA), or corporate political activism (CPA). Specifically, CSA has been receiving increasing scholarly attention (see [4,5,6,7,8]). Existing research has chiefly focused on investigating high-profile advocacy campaigns and conceptualizing CSA as a broader comprehensive term that includes different types of advocacy and political activity. However, the current body of literature provides limited insights to illuminate how the public attributes the responsibility of issues to companies and how they perceive companies as uniquely positioned to generate societal influence.

Several distinguished characteristics of Generation Z (born between 1997 and 2012, referred to as Gen Z in the remaining sections) provide a rich context to advance scholarly understanding of the changing expectations and complex thinking process. Gen Zers have greater awareness of issues surrounding race and diversity [9,10]. They are more likely to make ethical purchases to reduce environmental impacts [11], to be attuned to sustainability issues [12], and to be engaged in advocating for social issues [13]. Moreover, a recent global report found that 57% of Gen Z consumers are more attracted to companies that act on societal causes, and 34% of them are more willing to pay a higher price for brands that support issues they care about [12]. With their spending power rising to USD 143 billion [14], Gen Z has become a powerful demographic group that represents growing pressure and evolving expectations for companies’ engagement in the public agenda. However, not enough is known about Gen Z’s views on CSA and their expectations. Empirical studies focusing on unpacking the demand and perceptions of Gen Z will be instrumental in guiding organizations’ decisions to stay relevant to a consumer segment with increasing influence and spending power.

Consequently, the current study aims to fill this knowledge gap and gain further insight into this phenomenon by exploring how these young audiences expect companies to act on hot button issues and their reasoning process. Consistent with research practice when exploring new insights, new phenomena, or new light within phenomena or advancing new theoretical directions [15,16], we took an exploratory study approach previously used in similar contexts [17,18,19,20,21]. Specifically, we use closed and open-ended survey questions to investigate what Gen Z sees as companies’ responsibility to advocate for and act on issues like immigration, racial and gender inequality, vaccine mandates, climate change, etc. We thus uncover when and why these young stakeholders may expect companies to address (or not) social and political controversies. The results reveal three essential themes of the underlying cognition that drives their demands for CSA actions: attribution of responsibility, perception of control, and perceived fit. Our findings offer an audience-centric approach to understanding how companies’ public actions on divisive issues align with Gen Z’s expectations. To our knowledge, this research is one of the first qualitative inquiries aiming to rigorously describe Gen Z’s perspectives on CSA and generate testable hypotheses for future studies. Accordingly, the current study benefits the aim of this Sustainability’s special issue “Corporate Social Responsibility, Corporate Social Advocacy, and Societal Change”, seeking “to enrich the body of knowledge on corporate social responsibility (CSR) and corporate social advocacy (CSA) communication” [22].

2. Literature Review

To guide our exploration, we begin by discussing three sensitizing concepts to reimagine what audience-centric perspective of CSA would emerge. Sensitizing concepts are “theories or interpretive devices that serve as lenses for qualitative study” ([23], p. 29). We focused the following literature review on three axes of existing research to explore major changes (or the beginning of some shifts) and deepen our analysis for understanding the audience reasoning process of companies’ CSA engagement.

2.1. From Corporate Social Responsibility to Corporate Social Advocacy

The literature on CSR is abundant, and scholars have focused on a plethora of directions and contexts, including the CSR channel, the impact on the public, and ethical practices [24]. Some looked at the financial implications [25]. Others explored stakeholders’ roles and perceptions [26] and even the role of CSR in crisis situations [27,28,29].

However, there has been a move from CSR toward engaging in often controversial socio-political issues in recent years and thus toward more advocacy and even corporate activism efforts [30,31]. Examples include taking stances on gun laws, same-sex marriage, racial issues, and immigration [32]. CSA is thus seen as a form of brand activism through which companies take a stance on controversial social and political issues [30,33]. Some scholars even differentiated CSA from solely corporate political activism because the latter takes a negative approach to speaking against controversial political measures [34,35]. The significant difference between CSA and CSR is that CSA weighs heavily on controversial societal issues, while CSR focuses on support of the general societal good [7]. Due to the nature of the controversy in CSA, how corporations respond and act strategically in CSA is uncharted territory that is not fully explored.

Considering the divisive political climate and polarized opinions on recent CSA campaigns, public relations scholars have paid close attention to the underpinning motivation of companies’ CSA efforts and the subsequent impacts on consumer attitudinal and behavioral outcomes. Current organization-centric conceptualizations of CSA emphasize the idea of making a public statement or taking a stand on social, political, economic, or environmental issues [33,36]. Accordingly, research has focused on different aspects of CSA, including financial impact [33], influence on various stakeholders and shareholders’ attitudes [30,32], consumer expectations [31], or the effect on controversial issue attitudes [37]. Two limitations are noted. First, these quantitative studies yield inconclusive results regarding the impact of CSA. Second, there is less research taking a holistic approach to inquire deeper into why audiences construct their interpretations and expectations of corporations advocating for social issues. Often, communicators in business-to-consumer sectors are left with limited to zero guidance on when, why, and how to engage in the public agenda. From communicators’ points of view, an in-depth description of salient factors shaping consumers’ interpretations of and expectations for CSA will be meaningful for rethinking business missions and tailoring communication activities.

2.2. From a Corporate-Centric Approach to an Audience-Centric Approach

To our knowledge, a paucity of studies has approached CSA from an audience-centric perspective. Among the limited studies, Li et al. [6] looked at the role played by consumer involvement in shaping individuals’ attitudes and behaviors vis-à-vis Nike’s Kaepernick ad. Their most significant finding was that consumers’ support for CSA could be influenced by their involvement in that brand and the chosen CSA issue. On the industry and audience side, Edelman’s Trust Barometer research has shown an eroding trust in governments, media, and experts for years. For example, in 2019, Edelman, the leading PR firm, stated “We are at the moment in time when trust in government is very low, and there is more sense of having to rely on business to stand up speak up, within the workplace as an employer or in the marketplace to customers” [38]. Then, in 2020, as the pandemic and racial and civil unrest were in full bloom, Edelman asserted “Purpose is no longer enough. Brands must take action through advocacy” [39]. Edelman [40] found people expected more from brands than to just “enrich” their lives. Consumers had higher expectations of brands and companies to help address or solve systematic problems that impacted most people’s lives. They expected brands to be a dependable provider, a reliable source of information, a protector or visionary problem solver, and a positive force in shaping their culture. In 2021, businesses were the most or nearly the only trusted actors compared with NGOs, governments and media, and they were the ones seen as most competent and ethical ([41], pp. 6–7).

Moreover, consumers raised concerns about whether societal leaders do what is right, and consequently, they expected businesses to fill the void left by the government [42]. When it comes to Gen Z, recent reports indicate they expect companies to support the issues they care about [12] and, more importantly, beyond self-interest, the issues deemed necessary for society, such as racial justice or climate change [43]. For example, Gen Z expects beauty brands to change their practices and advocate for issues such as diversity and inclusivity [44]. While preliminary reports show that Gen Zers appear to value companies that take a stance on important issues, not enough is known about what they expect, especially concerning the reasons beyond their expectations. Therefore, a systematic investigation unpacking shifting consumer values and expectations of companies’ roles helps the scholarly discussion and communication practice.

2.3. From Attribution of Responsibility to Perceptions of Responsibilities

Generally, attribution theory (within a communication context) is used to explore how and why individuals explain occurrences, negative or positive events, other people’s behaviors or actions, etc. [45,46]. One focus became responsibility, or attributions about the cause of an action or an individual’s behavior [44]. In other words, attributions are about who or what is perceived as responsible for a specific behavior or outcome [47]. In the CSA context, as Lim and Young [48] illustrated, the strategic approach of CSA starts from identifying corporations’ responsibility to certain issues and whether they should take actions that fit the companies’ missions. However, little is known about how and to whom individuals assign responsibility for taking a stance or solving hot button issues. Meanwhile, the literature is rich with existing works on the attribution of responsibility in crisis situations [49] or CSR contexts post-failure or crises [50]. In a CSA context, Kim et al. [5] applied attribution theory to explore the role of perceived motives in developing individuals’ attitudes and word-of-mouth intentions vis-à-vis Nike’s CSA Kaepernick campaign.

Beyond that, a few studies looked at responsibility and the locus of control in the context of individual proactive actions. Generally, the locus of control refers to an individual’s perception of who has control over an (event’s) outcome: the individual (internal locus of control) or forces outside the individual (external locus of control) [51]. It was further refined to include perceived individual or self-control (internal), other actors (powerful others), and chance [52]. The concept of perceived control has been examined to explore behaviors and intentions in health and especially in environmental contexts [53,54,55]. For example, Fielding and Head [56] explored the determinants of young individuals’ environmental actions and found that attribution of responsibility to certain actors and their loci of control influenced their environmental actions. The sense of control one has over specific outcomes is essential.

Beyond responsibility, the concept of fit is considered essential when deciding specific CSR actions and seems to also be somewhat applicable to CSA contexts. Multiple studies looked at the fit’s influence on CSR success (see, for example, [57,58,59]). In the CSA context, fit can be defined as “the perceived congruity between the advocated cause and the brand in regard to the brand’s identity and the public expectations about the values related to the brand” ([48], p. 4). More importantly, scholars call for CSA efforts moving beyond brand matching and into aligning with “the changing social and cultural values among key stakeholders” beyond just the shareholders (p. 4). Together, CSA conceptualizations, models, and frameworks are still developing [48]. The extant definitions and conceptualizations are instrumental in studying existing corporate actions in responding to contentious issues. However, how business-to-consumer sectors could aptly adopt changing expectations among young adults is less understood.

3. Study Objectives and Research Questions

Guided by these sensitizing concepts, this study aims to foreground consumer expectations and interpretations to develop a framework embodying an audience-centric view of CSA. Gen Z provides an appropriate context for an initial attempt to investigate corporations’ strategic approaches to CSA because of their increasing spending power and high awareness of and engagement in the public agenda [12,14]. They might consider specific types of issues to be more controversial, concerning them, or important for business-to-consumer (B2C) corporations to take public stances for the wellbeing of society. Ideally, shifting from an organization-driven CSA approach to an audience-centric framework allowed us to uncover when and why stakeholders expect corporations to address or not address social and political controversies. Consequently, we posed the following research questions:

- RQ1: What are the types of issues that Gen Z audiences expect a company to take a stance on?

- RQ2: How do Gen Z audiences rationalize their views on whether companies should take a stance on different issues?

- RQ3: What are the specific arguments given by Gene Z audiences for their expectations of companies’ (non)involvement in these issues?

4. Method

The IRB office at a U.S. public university approved the study. A non-probability convenience sampling method was justified given the exploratory nature of our study [23,60]. Data collection was conducted via the first author’s university student participant pool (SONA system), serving 4 large academic units with up to 7000 diverse students. Students who registered to be part of the system could sign up for any study in which they were willing to participate in exchange for extra credit for courses that offered that option. Eligible participants were invited to take a short survey in exchange for extra credit during November and December 2020. A total of 388 participants completed the research (female: 74%; white: 71%; Hispanic: 22.4%; 18–24-year-olds: 92%).

Expected companies’ engagement in highly charged issues was measured on a 5-point scale from 1 (“definitely should not take a stance”) to 5 (“definitely should take a stance”). We selected eight controversial topics based on Pew Research’s recent polling data of the most pressing issues facing the U.S.

Utilizing open-ended questions was recommended in this type of phenomenological study because we aimed to explore the cognitive expectations of CSA among young consumers [61]. Open-ended questions allowed more detailed and in-depth understanding of a complicated social phenomenon that emphasizes participants’ voices and creates multiple perspectives or views of the phenomenon [61]. Participants were asked to articulate their reasoning to justify their thoughts on companies’ (non)involvement in addressing pressing issues.

We employed an inductive process whereby we closely followed the best practices in qualitative research [61,62,63]. Given this study’s exploratory nature, this approach best allowed us to discover the emerging views and reasons behind participants’ thoughts about organizations’ CSA stances on controversial issues. The existing literature on CSA constituted a starting point and a guide for analysis but not a pre-set coding sheet. The research team members read and reread the data multiple times. Each iterative reading led to the identification of codes and their further refining. Next, we clustered similar codes into higher-order themes. Once all the themes and sub-themes became clear and redundant, the best exemplification quotes were chosen, and the rest of the data were further systemized. All these steps ensured the findings truly emerged from the data and that the analytical rigor and credibility as defined in this type of qualitative methodology [23,61,62,64,65] were achieved. The computer-assisted qualitative data analysis software NVivo was used [66,67] to aid in coding the data and in the visualization of these themes and sub-themes as well.

5. Results

To answer RQ1, we conducted exploratory factor analysis because the completed responses to the closed-ended questions exceeded the minimum sample size required for yielding reliable results [68,69]. A principal component analysis with oblique rotation was used. We followed the Kaiser criterion of eigenvalues greater than one and used a scree plot to determine the number of factors. The items were retained if they met the absolute loading criterion of 0.40 and did not cross the load on more than one factor. The EFA results found two dimensions underlying the audience’s expectations, explaining 73.5% of the variance. As summarized in Table 1, the first dimension of issues was that companies should take a stance centered on essential health and safety needs, including health care affordability, gun control, immigration, abortion, and vaccination mandates. The second dimension of issues focused on justice and rights (e.g., climate change mitigation, racial inequality, and LGBTQ+ rights). The participants expected corporations to explicitly support justice and rights (M = 4.01) because of high levels of perceived issue importance.

Table 1.

Results of exploratory factor analysis for audience expectations of corporate social and political advocacy (CSPA) in salient issues (n = 388).

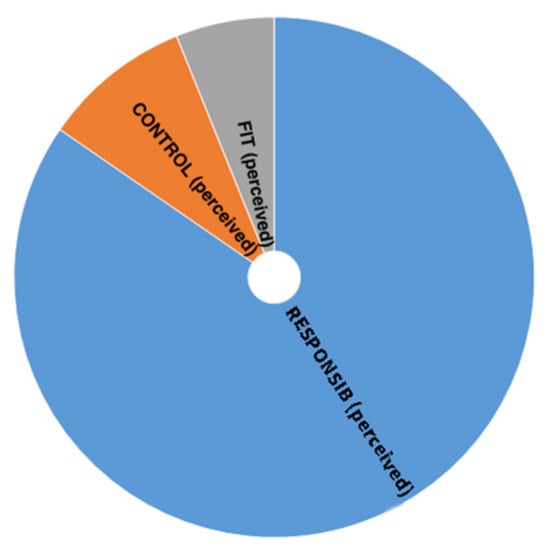

RQ2 and RQ3 asked how Gen Z audiences think about how much companies should (or should not) take a stance on these given issues and the underlying logic of their reasoning process. To answer RQ2 and RQ3, an inductive and iterative thematic analysis of the in-depth responses to the open-ended survey questions yielded the following powerful insights (in the order of power and frequency in the data): the attribution of responsibility to make a societal change on given issues by changing public attitudes and behaviors and the difference in the perceived types of issues, perception of personal, corporate, or societal control, and the concept of fit. Figure 1 shows a hierarchical visualization of these three main themes. These themes and sub-themes were often intertwined in the respondents’ answers, but they are presented in their hierarchy order and separated for more precise organization. We used accompanying examples to support the claim for every theme.

Figure 1.

NVivo sunburst view of the main coded themes.

5.1. First Dominant Theme: Attributions of Responsibility

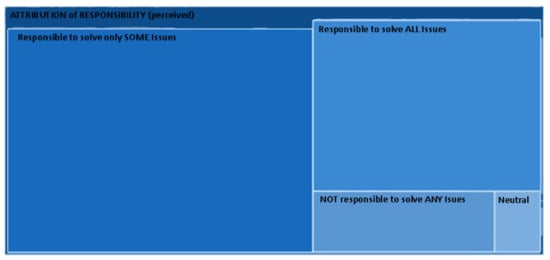

This idea of whose responsibility it is to fix or improve these types of issues was the most prevalent in participants’ explanations of why they thought companies should or should not get involved. The data revealed different subthemes of attribution of responsibility when it comes to who is perceived as responsible for solving what types of issues (Figure 2): companies are responsible for solving only some issues; companies are responsible for solving ALL these issues; companies are NOT responsible for solving any of these issues, and neutral. Finally, as they explained their stances, the participants gave various arguments, as presented for each of these dimensions.

Figure 2.

NVivo hierarchical treemap of attribution of responsibility sub-categories.

5.1.1. Companies Are Responsible for Solving Only Some Issues

The main dimension in terms of attributions of responsibility was the idea that companies are responsible for solving only some of the given issues. Participants gave different arguments for their reasoning.

Magnitude

Often, the participants argued that only some of those given issues are big societal ones, so companies are responsible for those or should address those first. For example, one respondent wrote “I feel like the ones I selected for definitely should take a stance are ones that seem to have the biggest impact in our society”. Another participant argued how the magnitude of some issues should make them a priority: “Climate change erases all the other issues we have. If we do not combat it, we won’t have a planet to live on”.

Social or Political vs. Personal Issues

Another argument was the respondents’ distinction between what they perceived as social vs. political vs. individual or personal issues. They saw companies as only responsible if they took a stance (and many times solved) those social issues but stayed away from those deemed as “too political” or “too personal”. The following quotes exemplify this: (1) “The issues I feel companies should take a stand on are more social issues, rather than political”, and (2) “Because some of these things can be considered a “political issue”, but others are issues that just involve basic human decency”. Interestingly, which issues were seen as political or social vs. personal differed at points, as the following three quotes show: (1) “I don’t think large corporations should have much of a stance on healthcare, abortion, or vaccinations because these are all matters of one’s health”; (2) “I believe if concerns the health and safety of U.S. citizens, it should be covered. But for example, abortion is one’s private and personal decision, therefore it should not be”; and (3) “Abortion, gun control, and vaccines I think are all personal choices, which companies shouldn’t have a stance on. They can be for abortion or against it but because they are not the ones having to go through that they shouldn’t get to decide if someone has an abortion or not”. Furthermore, others argued that for some of the more “political” issues, they did not think companies should take a stance because they cannot be trusted. For example, one respondent argued that companies could not be impartial since they might be funded by a particular political side:

“I think it’s important for companies to take a stand on issues like climate change, racial and ethnic inequality, LGBTQ+ rights, and animal rights because those companies often contribute directly to how those issues are handled. However, these same companies might be backed financially by powerful organizations with specific stances, like the NRA, therefore making them biased on such issues. I think a company’s public opinion holds less value if they have a financial motivation to promote a certain belief.”

Controversy or Divisiveness Level

Another argument respondents brought up was the idea that companies should maybe just focus on “non-controversial” issues. For example, one respondent argued the differences between issues that are too controversial and those that have to do with equality or the good of the planet.

“I think that boxes I clicked for definitely have to do with equality. I believe that men and women should have equal rights no matter where they come from, what they look like, their race, who they love, etc. I also believe that companies can have climate change initiatives that promote having a greener world. I think that gun control is a really controversial topic and that it’s probably best for companies not to take a stance on that topic.”

Other examples include the concept of being too divisive or not socially accepted: (1) “They are the least political issues and are the ones likely to cause the least division among Americans”; (2) “climate change is a more socially accepted issue by everyone. Therefore, it would be a safe issue to endorse. While all of the other issues are highly controversial and could hurt a company if they endorsed the wrong side”; and (3) “Certain topics are not socially acceptable yet”.

Possible Impact

Another prevalent argument was the idea of impact. The respondents argued that companies should take a stance only on the issues they can impact or ones in which they can influence the public at large, as demonstrated in the following two examples: “Mostly healthcare, climate change, and racial inequality should be the most important to companies as it is the issues they can have the best impact and the most influence over”, and “I think the issues of climate change, inequality, LGBTQ+ rights, and animals right are all issues that companies can actually make a difference in. For example, a company could provide products that involve animal rights or provide more environmentally sustainable products”. Again, differences emerged in the type of issues respondents thought companies can solve. While many included climate change, others thought the issue goes beyond a company’s ability: “If a company could make a difference for these issues I said they maybe should take a stance, but for issues that I believe a company doesn’t really have a say in a said maybe not. So, for example, I said maybe not for climate change because it’s not really something that a company can change”.

Others argued companies are responsible for the issues that impact their company environments directly, as the following examples show: (1) “I believe that gun control, climate change, and racial and ethnic inequality should be taken a stand on by companies because it could affect the safety of their customers and employees”; (2) “Because some of these affect companies when it comes to how they are run and what they stand for”; (3) “the problems that would affect them are important issues for them to take a stance on”; and (4) “For some issues too, there is a direct impact on the industry of some companies, and as such they should have a position on the topic”.

Yet another argument was the impact taking a stance has for a company in terms of reputation, employees, and consumers. Here, the respondents brought up more general and more specific impacts. The following two examples illustrate the more general impact: “Because I feel like companies should support certain stances which would eventually help the company and their reputation”, and “I chose some of these public issues as important for companies to take a stance on because each of these issues have far-reaching societal impacts. As consumers I believe we have the right to know where companies stand on certain issues, and then we can choose who to support with our dollars”. The respondents who included more specific impacts referred especially to racial justice and human rights issues, as the following two examples show: “I believe that for companies to have a great outlook and maintain their employees they need to take a stance on many social and political issues. especially for racial and immigration issues, in these days we are living in that can make or break your business as well as start making a change by leading by example”, and “Anything that could promote a company as being inclusive of all is a good thing. You would hate to lose customers because you were not in for equal treatment for all or against LGBTQ rights”.

Causality Dictates Responsibility

Another argument present in respondents’ answers was the idea that companies are responsible for taking a stance only on issues they cause or contribute to. The following two examples illustrate this: “Climate change should be addressed because of how companies participate in the destruction of the environment”, and “I chose the answers for the questions above because there are some issues that are directly impacted by the companies/brands. Climate change for example is largely impacted by companies/brands because of their manufacturing and shipping, companies should be more aware of what they are doing to the environment”. Other respondents were more personal and argued for the responsibility to address the “overlooked” issues or issues they believed directly affected them or their families. The issues were very different depending on the respondents’ specific circumstances, from equality to gun issues. For example, one respondent argued “Personally I don’t think LGBTQ is an important issue and people make it too big of a deal, I also personally believe that gun issues are huge and we should not be stripped of our right to carry/own firearms, immigration needs to be put under control for the sake of our country, etc.”, while another said “The issues I think companies should choose to take a stance on are issues that are important to me and what I think is vital to living a life where everyone is equal”.

5.1.2. Companies Are Responsible for Solving All These Issues

This was the second most encountered dimension of the respondents’ rationale for companies’ responsibility to take or not take stances on the given issues. Again, the respondents gave different yet intertwined arguments.

Higher Power to Solve All

One argument given was the belief that companies are responsible for solving all the given issues because they might be the only actors with the power to fix things. For example, one respondent saw companies as higher powers: “Because once higher powers start to take stances, then the world will see change needs to be made”. Another argued that “I believe all of these issues are something they should take a stance on. The issues shown in this research are issues that have now been attempted to be fixed and do right for and those issues should not take this many years to fix as they are clearly creating a massive problem to our country”.

All Issues Matter

Another prevalent argument was the idea that all issues matter equally and are significant, and companies are responsible for taking a stance on all of them. One respondent argued “I put for all of them to have a stance taken upon them because this is our world and society we live in we need to be focused on what’s around us and as much as some people don’t want to admit all of those things on the list are very important. and should be taken seriously”. Another emphasized the need to help: “All of those public issues are very important. […]. If companies took a stance on public issues more would be done to help”.

Snowball Effect

The respondents believed that once companies get the ball rolling on all these equally important issues, others would become aware, and others would take action. For example, one respondent said “The public will see that companies find these issues enough to intervene and they will believe that it is something they should dig into as well”. Other examples include the following: “It is important for companies to take a stance on most all of these issues because they have such a huge platform to raise awareness on public issues”, and “Most of our companies hold a high place on social media and public view. If they were all to be involved in support of all these rights, we would have more awareness”.

Affected by All Issues

The respondents also argued that companies are responsible for solving all issues because they equally affect their companies and not just society or individuals. One wrote that “These issues are more than just politics; they concern people’s lives and wellbeing. If a company does not support LGBTQ rights, access to affordable healthcare, immigration, or access to safe abortions, then I do not want to support that company”. Another respondent argued “[…] in these days we are living in that can make or break your business as well as start making a change by leading by example”.

5.1.3. Companies Are Not Responsible for Solving Any of These Issues

A third dimension of the respondents’ rationale for companies’ responsibility to take or not stances on the given issues was the idea that companies are not responsible for being involved in these issues. Again, multiple arguments were used to rationalize this opinion.

Business Only

One prevalent argument was that companies are there just for business purposes, which excludes any involvement in any issues. For example, one respondent said “I feel like companies should not state what they support because it has nothing to do with their business”. Another one argued “I don’t think it should be a company’s responsibility to take a stance. We are using that company for other reasons; what they think we should do about abortion shouldn’t be important. Only the quality of their products”. Here, most respondents felt a company should only be responsible for selling their products or services. The following examples illustrate this: “Because the company should be concerned with selling their product, not how their customers FEEL”, and “Business is there to sell a product, not a political opinion”.

Unequal Representation

Some respondents argued that no issue will ever represent all the company members, and therefore, they should not advocate for any issues. For example, one respondent said “The stances only reflect a select few in the company. The people are diverse, so the stance does not accurately reflect the actual company”.

An Exception to the Rule

Exceptions were allowed. Namely, respondents argued the exception to this rule can be made only for those organizations that are solely advocacy-based. The following two examples showcase this argument: “I don’t think it is the right of the company to take a stance on these issues. […] however, unless it is an organization founded to advocate for one of these issues, they shouldn’t get to take a stance”, and “Some companies were founded and created to deal with specific issues, so sometimes it is their very job to take stances on different issues”.

CEOs vs. Companies

In this sense, the respondents distinguished a difference between companies and CEOs. They argued that only CEOs could take a stance. One respondent wrote “Companies should not take a stance as a whole, if the leaders of a company wish to take a stance they should do so as individuals rather than a collective”. Another respondent argued “Companies should not be used as political weapons to swing their weight around based on what the CEO supports politically”.

Skepticism of Perceived Motivation

Finally, the argument that companies should not get involved with any issues because they cannot be trusted was also present in respondents’ answers. Responders feeling this way argued that when companies take a stance, it is just for PR or for money. Therefore, they should not take stances. The following examples showcase this argument: “Company is for profit and the stance is only pandering for dollars”, and “Nowadays, when companies do take [a] stand, they aren’t doing it out of concern…they are using it as a PR stunt”.

5.1.4. Neutral Views on Responsibility

A neutral view on responsibility was another dimension of the respondents’ rationale for companies’ responsibility to take or not stances on the given issues. In this context, respondents who remained neutral regarding how much companies should be involved and in which issues felt it should be up to the companies to decide, and no one should see them as responsible for certain things. For example, one respondent argued “I believe it is up to the company’s discretion if they believe any of the above are worth taking a stand on then that is up to them to decide if they will take a stand regarding that topic”. Another wrote “I don’t have any particular stance since I don’t believe it is my place to regulate the ability or morality of a corporation to provide a stance. Corporations, as larger entities, can help or hurt the public idea of individual concepts, leading to unfortunate side effects”.

5.2. Second Theme: Societal Control and the Perception of Personal vs. Corporate vs. Government

In the respondents’ rationalizations of whether companies should take a stance on issues, the concept of control emerged. The respondents argued that whether companies should get involved in all vs. some vs. no issues had to do with their perception of who is in control. For example, those arguing that companies should not take a stance on issues perceived as too “personal” argued that some things (e.g., abortion) are and need to remain in the control of the individual. The same was said for issues that are or should be in the control of the “government”. One respondent argued “There are some things that are reasonable to get involved with, but other things don’t need company involvement because they should be handled by the government and the people”. Another one wrote “No matter what ideas companies project, it’s up to lawmakers to make the morally and ethically right decisions to better our country”.

For others, individuals and governments have lost control on some occasions, while companies might be the only ones in control. These examples illustrate the argument: “Companies have a great impact as people tend to follow into their footsteps. They are also able to possibly make a bigger/stronger/faster impact than an average person alone”, and “Companies have a platform and connection and the capability to reach a broader audience and more minds than just a small group of people do”. Another respondent put it this way: “Because these are huge issues! Politicians only listen to money and maybe it takes the bigger guys to weigh in on it”. Finally, another respondent said “I believe all of these issues are something they should take a stance on. The issues shown in this research are issues that have now been attempted to be fixed and do right for and those issues should not take this many years to fixed as they are clearly creating a massive problem to our country”.

The idea of cooperation was also brought up: “Due to our community and nation, these issues are taken differently by many people, in order for us as a nation to make things right and correctly we need to work together in it”.

5.3. Third Theme: Perception of Fit

The third theme emerging in the respondents’ rationalizations was the concept of fit. However, such a theme was less prominent compared with the aforementioned attribution of responsibility and perceptions of control. For example, in their arguments for why companies should only take a stance on certain issues, the respondents said it should come down to the connection between the issues and the company’s purpose. One respondent argued “I think it depends on the company for sure. Companies should take stances on topics relevant to them. For example, it would make sense for Tyson or make-up companies to take a stance on animal rights, but it wouldn’t make sense for Amazon to do the same thing. For immigration, climate change, and racial and ethnic inequality, I think these are things that involve and impact most of our society, so it makes the most sense for any company to take a stance on these issues”. Another expressed similar views: “Some issues (i.e., racial inequality and LGBTQ rights) affect everyone in our society and have an effect on many companies and their environments. However, some issues only need to be addressed by companies that are directly involved with a certain issue (i.e., health organizations should address health insurance and vaccines, but a mass meat production company wouldn’t. Rather, a meat production company should address animal rights)”. One argued that fit should trump importance: “They are all important, some would just not be a right fit”. However, as the quote shows, those respondents still thought some of the issues transcended fit.

Finally, the argument that fit goes beyond a company’s purpose was also present; in other words, the idea that a company should only take a stance on issues related to their expertise was present. For example, one respondent argued “Some issues aren’t black and white and require expert knowledge to have an opinion (Like vaccination mandates or abortion), so companies taking a stance on hot-topic issues like these could create huge problems”.

6. Discussion

This exploratory study offers a rich description of how young audiences (Gen Z), as the future main shopping power, view corporate social advocacy and justify the appropriateness of companies’ CSA communication activities, specifically if, what, and when members of this consumer segment think companies should take a stance on controversial social and political issues and why. We were also interested in what arguments they used in this context. The findings suggest that young adults expect companies to take a stance on all or most of these issues. Gen Z tended to agree more that companies should publicly support diversity, racial and gender justice, climate change, and rights issues, lending support to existing suggestions [9,11]. Moreover, the findings reveal evolving expectations of how young audiences perceive the social responsibility of companies.

The perceived attribution of responsibility is the driving factor in how this audience sees the need for companies to take a stance on issues, an omitted aspect in the current CSA literature. As the findings suggest, most respondents saw companies as responsible for solving all or most of the issues. This was either because these Gen Zers see all or most of the given issues as essential for the wellbeing of our society and future or because they perceive companies might hold more control and power than other actors. In contrast, those who saw companies’ roles as solely to make profits and provide products argued they are not responsible for anything beyond that. These findings also suggest that audiences may be judging CSA efforts similarly to how they judge companies in a crisis. This underlines the importance of making the right decisions when acting or not acting on these types of CSA issues. Recognizing this challenge also stresses the value of further investigation of the strategic approach to CSA.

Furthermore, the results show a connection between the attribution of responsibility and perceived control. These Gen Zers believed that since all the other social actors failed, companies might be the only ones left in control of these issues. The results show that when the perceived powerful others are high and perceived individual control is low, the attributions of responsibility and expectations of action are focused on those perceived as powerful (i.e., companies). Consequently, the companies have the responsibility to fix systematic issues. In this case, the government and other actors have low perceived control. The results thus echo environmental behavior research [53,54,55]. These results also resonate with Edelman’s reports from 2019 and 2020 in terms of low trust in governments and governmental actors. It provides additional context into how these young adults rationalize their expectations, which can in turn help companies decide their CSA activities and messages.

Additionally, one of the more surprising findings was that perceived fit (between company and issue) was the least important factor for this audience when deciding what issues (if any) companies should take a stance on. This is sharply contrary to the CSR context, where fit was shown to be an important variable for a company’s success [57,58,59]. For example, if a company was in the fashion industry, it made sense for their CSR efforts to be related to animal rights. When it comes to CSA and the given issues, the results indicate the organization’s profile, and the issue fit might not be that important in how Gen Z audiences assign responsibility. The results suggest that the fit with stakeholders’ changing values might be more important than the fit with the brand itself [40]. Although such findings are tentative in nature, the audience’s minimal emphasis on perceived fit between the engagement in social issues and the core business functions challenges conventional thinking to move toward a need for alignment with target audiences’ expectations and interpretations.

Furthermore, it may be more related to whom these audiences see as able to solve these issues, especially when this is seen as vital for humankind’s wellbeing vs. their own interests, supporting recent industry findings [43]. This marks an essential change; corporations are now seen as responsible for doing what traditionally only governments did. Thus, the perceived responsibility grows from a CSR level (companies should focus on related issues) to a higher CSA level (companies need to fight systematic issues such as climate change or racial discrimination). In this significant shift, where young adults attribute more and more responsibility from governments to B2C companies, the companies begin to be perceived as civic—not solely economic—actors. Thus, organizations need to show the young generations how responsible they are for public issues to respond to their prominent expectations of CSA efforts (e.g., Coca-Cola might be seen as responsible and taking action on big societal issues, even if that might not be directly related to their business). The number of survey respondents who applied the old argument that a company’s business is just business was minimal, with a majority arguing that it is not just business as usual anymore, that companies are civic actors like participants themselves, and everyone is civically responsible.

7. Conclusions

This exploratory study aimed to fill the gaps and illuminate new insights related to CSA and the need for further theory building. Previously, most CSA studies focused on quantitative explorations of high-profile advocacy campaigns and an organization-centric approach. Our qualitative inquiry allowed for the uncovering of an overlooked reasoning process of young consumers from Gen Z. None of the previous studies looked specifically at audiences and consumers who were part of Generation Z. Through an exploratory inquiry of Generation Z’s responses to a timely online survey, we identified three essential themes to shed light on the underlying motivation and considerations of how young audiences perceive companies’ CSA. First, the level of attribution of responsibility and the perceived locus of control were frequently articulated as the guiding argument to support respondents’ divergent viewpoints of CSA. Our findings advance the literature by centering audiences’ expectations and interpretations in guiding organizations’ decisions to stay relevant with aligning with young consumers’ unique values. While this study is exploratory in nature, these young adults provide a temperature check nonetheless, and they indicate that at their level as knowledgeable stakeholders, major changes occurred in their vision of social responsibility and corporate advocacy. It seems that decades of the CSR literature and common practice might not be enough or an end-all. Gen Zers believe companies have a responsibility to fight on topics that might be controversial but are seen as major. Corporations must fight because they are civic actors who thus have to solve these issues.

This investigation of these young adults brings several contributions to the extant literature on CSA perceptions. First, these Gen Z stakeholders clearly believe companies have a responsibility to fight on topics that might be controversial but are seen by them as major social issues and which, in turn, should trump controversy or politics. They see companies as responsible to fight for these issues because they are civic actors who must be part of the solution. Second, they consider that companies must take many of the duties of governmental actors and institutions and that they must carry out actions traditionally situated in the field of public policies. This phenomenon is related to the general erosion of trust in government, administration, and all those other entities that were traditionally trusted. Third, their main argument for these expectations is no longer just about responsibilities but about having money and power. Lastly, contrary to previous studies, especially those on CSR where an essential factor was the fit between a company’s business or organizational profile and the issues they decided to address, in this case of CSA, they cared less about fit. In fact, their expectations and arguments suggest that the perceived attributions of responsibility for companies to address and take a stance on all or most of these issues go beyond their business profile. Thus, the potential for corporations to improve societal wellbeing trumps the issue–business fit.

Despite the contributions, this study also has limitations. First, the quantitative EFA results should be interpreted with caution, as the sample does not represent the US’s overall larger population, even in terms of Generation Z. Future research examining the factor loading structure of issue categories that companies should take a stand on with a national adult sample is desirable to explore potential changes in the perceptions of different generational cohorts. Currently, our next step is to survey a nationally representative sample of US individuals to validate the preliminary findings presented in the study and identify what other important perspectives might emerge. Second, the inherent selection bias associated with convenience samples might exist, as we did not require open-ended questions for survey participants. Free responses might be generated from those who were highly interested in providing their thoughts. The selection bias was ameliorated, as over 96% of the survey participants voluntarily responded to a set of open-ended questions, allowing us to distill the driving factors associated with Gen Z’s CSA expectations from a rich dataset. Third, a majority of the participants’ qualitative responses gravitated toward B2C corporations, partly because these corporations communicated their CSA efforts on social media platforms Gen Zers consistently use in their daily lives [9]. Thus, an investigation focusing on the context of B2B corporations will complement the literature. Lastly, it is important to note the purposes of qualitative analysis are not to generate universal predictions. This study offers rich descriptions to reimagine an audience-centric framework that focuses on less studied concepts: perceptions of responsibility, ideas of control, and value alignment.

Nevertheless, this study remains worthy, as insights from Gen Zers are theoretically relevant and practically applicable. The expectations and interpretations of CSA from young consumers present an opportunity for social transformation and for scholars and practitioners to rethink the foundational civic role of companies. Gen Zers are knowledgeable of pressing social issues and have expressed clear preferences for companies who support issues not only aligned with their own values but deemed as critical for societal wellbeing. Engaging in CSA or not is uncharted territory for public relations scholars and practitioners. Our study represents one of the first to offer in-depth insights into understanding when and why Gen Z expects companies to take action and the divergent reasons for their explanations. Our findings are also on-trend with Edelman’s. Stating a brand’s purpose is indeed “no longer enough” [39].

Author Contributions

Conceptualization I.A.C., S.Y. and J.-Y.T.; methodology, all authors; data analysis led by I.A.C.; all authors contributed to writing and editing. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Review Board of Texas Tech University.

Informed Consent Statement

All participants in the survey gave informed consent to participate in the survey.

Data Availability Statement

The data are not publicly available due to IRB regulations.

Acknowledgments

We thank the special issue editors, the Page Center, and the reviewers.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Austin, L.; Gaither, B.; Gaither, T.K. Corporate social advocacy as public interest communications: Exploring perceptions of corporate involvement in controversial social-political issues. J. Public Interest Commun. 2019, 3, 1–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christie, D. Kantar. Consumers Want Brands to Take Stance on Social Issues, but Demographic Divides Remain. 2020. Available online: https://www.marketingdive.com/news/kantar-consumers-want-brands-to-take-stance-on-social-issues-but-demograp/579618/ (accessed on 20 December 2021).

- Yamanouchi, K.; Kempner, M. Delta, Coke Face Boycott Campaigns over New Georgia Voting Law. The Atlanta Journal-Constitution. 2021. Available online: https://www.ajc.com/news/business/delta-coke-face-boycott-campaigns-over-new-georgia-voting-law/ZJUGGDO3HBA3BF2J64WVOQ5YE4/ (accessed on 20 December 2021).

- Gaither, B.M.; Austin, L.; Collins, M. Examining the case of DICK’s sporting goods: Realignment of stakeholders through corporate social advocacy. J. Public Interest Commun. 2018, 2, 176–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.K.; Overton, H.; Bhalla, N.; Li, J.Y. Nike, Colin Kaepernick, and the politicization of sports: Examining perceived organizational motives and public responses. Public Relat. Rev. 2020, 46, 101856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.Y.; Kim, J.K.; Alharbi, K. Exploring the role of issue involvement and brand attachment in shaping consumer response toward corporate social advocacy (CSA) initiatives: The case of Nike’s Colin Kaepernick campaign. Int. J. Advert. 2020, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Overton, H.; Choi, M.; Weatherred, J.L.; Zhang, N. Testing the viability of emotions and issue involvement as predictors of CSA response behaviors. J. Appl. Commun. Res. 2020, 48, 695–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Overton, H.; Kim, J.K.; Zhang, N.; Huang, S. Examining consumer attitudes toward CSR and CSA messages. Public Relat. Rev. 2021, 47, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pichler, S.; Kohli, C.; Granitz, N. DITTO for Gen Z: A framework for leveraging the uniqueness of the new generation. Bus. Horiz. 2021, 64, 599–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, K.; Graff, N.; Igielnik, R. Generation Z Looks a Lot Like Millennials on Key Social and Political Issues. Pew Research. 2019. Available online: https://www.pewresearch.org/social-trends/2019/01/17/generation-z-looks-a-lot-like-millennials-on-key-social-and-political-issues/ (accessed on 10 December 2021).

- Djafarova, E.; Foots, S. Exploring ethical consumption of generation Z: Theory of planned behaviour. Young Consum. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barton, R.; Morath, J.; Quiring, K.; Theofilou, B. Generation P(urpose). From Fidelity to Future Value. Available online: https://www.accenture.com/_acnmedia/pdf-117/accenture-generation-p-urpose-pov.pdf (accessed on 20 December 2021).

- Annie Casey Foundation. 2021. Available online: https://www.aecf.org/blog/generation-z-social-issues (accessed on 20 December 2021).

- Kim, S.; Austin, L. Effects of CSR initiatives on company perceptions among Millennial and Gen Z consumers. Corp. Commun. Int. J. 2019, 25, 299–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saunders, M.; Lewis, P.; Thornhill, A. Research Methods for Business Students, 5th ed.; Pearson Education: London, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Singleton, R.; Straits, B. Approaches to Social Research, 5th ed.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Sobczak, A.; Debucquet, G.; Havard, C. The impact of higher education on students’ and young managers’ perception of companies and CSR: An exploratory analysis. Corp. Gov. Int. J. Bus. Soc. 2006, 6, 463–474. [Google Scholar]

- Ahrweiler, F.; Neumann, M.; Goldblatt, H.; Hahn, E.G.; Scheffer, C. Determinants of physician empathy during medical education: Hypothetical conclusions from an exploratory qualitative survey of practicing physicians. BMC Med. Educ. 2014, 14, 122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Berry, J. Canadian public relations students’ interest in government communication: An exploratory study. Manag. Res. Rev. 2013, 36, 528–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loveys, K.; Hiko, C.; Sagar, M.; Zhang, X.; Broadbent, E. “I felt her company”: A qualitative study on factors affecting closeness and emotional support seeking with an embodied conversational agent. Int. J. Hum. Comput. Stud. 2022, 160, 102771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez Gómez, F.; Munuera Gómez, P. Use of MOOCs in Health Care Training: A Descriptive-Exploratory Case Study in the Setting of the COVID-19 Pandemic. Sustainability 2021, 13, 10657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rim, H.; Overton, H. Corporate Social Responsibility, Corporate Social Advocacy, and Societal Change. Available online: https://www.mdpi.com/journal/sustainability/special_issues/CSR_CSA (accessed on 18 February 2022).

- Tracy, S.J. Qualitative Research Methods: Collecting Evidence, Crafting Analysis, Communicating Impact; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Bortree, D.S. The state of CSR communication research: A summary and future direction. Public Relat. J. 2014, 8, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Cho, S.J.; Chung, C.Y.; Young, J. Study on the Relationship between CSR and Financial Performance. Sustainability 2019, 11, 343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- John, A.; Qadeer, F.; Shahzadi, G.; Jia, F. Getting paid to be good: How and when employees respond to corporate social responsibility? J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 215, 784–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ham, C.D.; Kim, J. The role of CSR in crises: Integration of situational crisis communication theory and the persuasion knowledge model. J. Bus. Ethics 2019, 158, 353–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Austin, L. Corporate social responsibility and responsibility. In Social Media and Crisis Communication, 2nd ed.; Jin, Y., Austin, L., Eds.; Routledge: Abingdon-on-Thames, UK, 2022; Volume 2, pp. 48–59. [Google Scholar]

- Rim, H.; Ferguson, M.A.T. Proactive versus reactive CSR in a crisis: An impression management perspective. Int. J. Bus. Commun. 2020, 57, 545–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hydock, C.; Paharia, N.; Blair, S. Should your brand pick a side? How market share determines the impact of corporate political advocacy. J. Mark. Res. 2020, 57, 1135–1151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.; Lee, E.; Rim, H. Should businesses take a stand? Effects of perceived psychological distance on consumers’ expectation and evaluation of corporate social advocacy. J. Mark. Commun. 2021, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhagwat, Y.; Warren, N.L.; Beck, J.T.; Watson, G.F., IV. Corporate sociopolitical activism and firm value. J. Mark. 2020, 84, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dodd, M.D.; Supa, D.W. Conceptualizing and measuring “corporate social advocacy” communication: Examining the impact on corporate financial performance. Public Relat. J. 2014, 8, 1–23. [Google Scholar]

- Korschun, D.; Aggarwal, A.; Rafieian, H.; Swain, S.D. Taking a Stand: Consumer Responses to Corporate Political Activism; SSRN; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Clemensen, M. Corporate Political Activism: When and How Should Companies Take a Political Stand? Unpublished Master’s Project; University of Minnesota: Saint Paul, MN, USA, 2017; Available online: https://conservancy.umn.edu/bitstream/handle/11299/189490/Clemensen%2C%20Maggie%20-%20Corporate%20political%20activism.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y (accessed on 5 December 2021).

- Eilert, M.; Cherup, A.N. The activist company: Examining a company’s pursuit of societal change through corporate activism using an institutional theoretical lens. J. Public Policy Mark. 2020, 39, 461–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parcha, J.M.; Kingsley Westerman, C.Y. How corporate social advocacy affects attitude change toward controversial social issues. Manag. Commun. Q. 2020, 34, 350–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marszalek, D. Edelman: ‘Brands Use Societal Issues as a Marketing Ploy’. PRovoke Media. 2019. Available online: https://www.provokemedia.com/latest/article/edelman-'brands-use-societal-issues-as-a-marketing-ploy' (accessed on 10 December 2021).

- Maicon, L. Purpose Is Not Enough: Brand Action Through Advocacy. Edelman. 2020. Available online: https://www.edelman.com/research/purpose-not-enough (accessed on 10 December 2021).

- Edelman Trust Barometer. Global Report. 2020. Available online: https://www.edelman.com/sites/g/files/aatuss191/files/2020-06/2020%20Edelman%20Trust%20Barometer%20Specl%20Rept%20Brand%20Trust%20in%202020.pdf (accessed on 10 December 2021).

- Edelman Trust Barometer. Global Report. 2021. Available online: https://www.edelman.com/sites/g/files/aatuss191/files/2021-03/2021%20Edelman%20Trust%20Barometer.pdf (accessed on 10 December 2021).

- Edelman Trust Barometer. Global Report. 2022. Available online: https://www.edelman.com/trust/2022-trust-barometer (accessed on 18 February 2022).

- Kitterman, T. Report: Gen Z Wants Brands to Stand Up for All—Not Just the Individual. PR Daily. 2022. Available online: https://www.prdaily.com/report-gen-z-wants-brands-to-stand-up-for-all-not-just-the-individual/ (accessed on 18 February 2022).

- Biondi, A. How Gen Z Is Changing Beauty. Vogue Business. 2021. Available online: https://www.voguebusiness.com/beauty/gen-z-changing-beauty (accessed on 20 December 2021).

- Manusov, V.; Spitzberg, B. Attribution theory. In Engaging Theories in Interpersonal Communication: Multiple Perspectives; Baxter, L.A., Braithewaite, D.O., Eds.; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2008; pp. 37–49. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, E.E.; Davis, K.E. From acts to dispositions the attribution process in person perception. In Advances in Experimental Social Psychology; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1965; pp. 219–266. [Google Scholar]

- Weiner, B. Attribution, emotion, and action. In Handbook of Motivation and Cognition: Foundations of Social Behavior; Sorrentino, R.M., Higgins, E.T., Eds.; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 1986; pp. 281–312. [Google Scholar]

- Lim, J.S.; Young, C. Effects of Issue Ownership, Perceived Fit, and Authenticity in Corporate Social Advocacy on Corporate Reputation. Public Relat. Rev. 2021, 47, 102071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coombs, W.T.; Holladay, S.J. Reasoned action in crisis communication: An attribution theory-based approach to crisis management. In Responding to Crisis: A Rhetorical Approach to Crisis Communication; Millar, D.P., Heath, R.L., Eds.; Routledge: Abingdon-on-Thames, UK, 2004; pp. 95–115. [Google Scholar]

- Siu, N.Y.M.; Zhang, T.J.F.; Kwan, H.Y. Effect of corporate social responsibility, customer attribution and prior expectation on post-recovery satisfaction. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2014, 43, 87–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rotter, J. Generalized expectancies for internal versus external control of reinforcements. Psychol. Monogr. 1966, 80, 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Levenson, H. Activism and Powerful Others: Distinctions Within the Concept of Internal-External Control. J. Personal. Assess. 1974, 38, 377–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Weber, A. Who can improve the environment—Me or the powerful others? An integrative approach to locus of control and pro-environmental behavior in China. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2019, 146, 55–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cleveland, M.; Kalamas, M.; Laroche, M. “It’s not easy being green”: Exploring green creeds, green deeds, and internal environmental locus of control. Psychol. Mark. 2012, 29, 293–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cleveland, M.; Robertson, J.L.; Volk, V. Helping or hindering: Environmental locus of control, subjective enablers and constraints, and pro-environmental behaviors. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 249, 119394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fielding, K.S.; Head, B.W. Determinants of young Australians’ environmental actions: The role of responsibility attributions, locus of control, knowledge and attitudes. Environ. Educ. Res. 2012, 18, 171–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Lee, H. The effect of CSR fit and CSR authenticity on the brand attitude. Sustainability 2020, 12, 275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Becker-Olsen, K.L.; Cudmore, B.A.; Hill, R.P. The impact of perceived corporate social responsibility on consumer behavior. J. Bus. Res. 2006, 59, 46–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Aksak, E.O.; Ferguson, M.A.; Duman, S.A. Corporate social responsibility and CSR fit as predictors of corporate reputation: A global perspective. Public Relat. Rev. 2016, 42, 79–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazzocchi, M. Statistics for Marketing and Consumer Research; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Creswell, J.W.; Poth, C.N. Qualitative Inquiry and Research Design: Choosing among Five Approaches; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Corbin, J.; Strauss, A. Basics of Qualitative Research: Techniques and Procedures for Developing Grounded Theory, 3rd ed.; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Bhattacharya, K. Fundamentals of Qualitative Research: A Practical Guide; Routledge: Abingdon-on-Thames, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Punch, K.F. Introduction to Social Research: Quantitative and Qualitative Approaches; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Silverman, D. Doing Qualitative Research: A Practical Handbook; Sage: Thousand Oakos, CA, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Feng, X.; Behar-Horenstein, L. Maximizing NVivo utilities to analyze open-ended responses. Qual. Rep. 2019, 24, 563–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chisanga, K.; Mbega, E.; Ndakidemi, P.A. Socio-economic factors for anthill soil utilization by smallholder farmers in Zambia. Sustainability 2019, 11, 4849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Goretzko, D.; Pham, T.T.H.; Bühner, M. Exploratory factor analysis: Current use, methodological developments and recommendations for good practice. Curr. Psychol. 2021, 40, 3510–3521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacCallum, R.C.; Widaman, K.F.; Preacher, K.J.; Hong, S. Sample size in factor analysis: The role of model error. Multivar. Behav. Res. 2002, 36, 611–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).