Sustainable Consumption Research and the Role of Marketing: A Review of the Literature (1976–2021)

Abstract

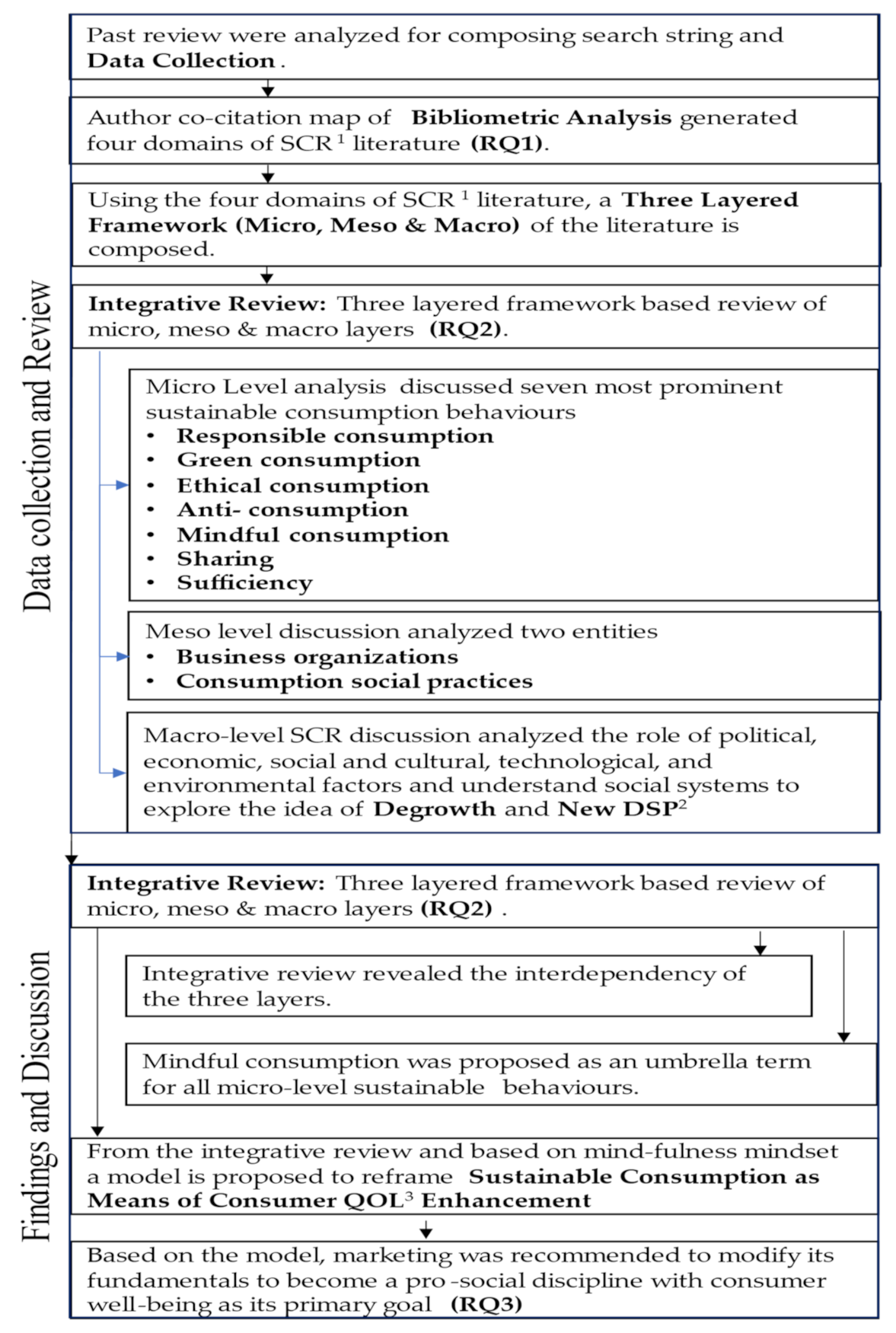

1. Introduction

- RQ1

- What are the main features of the SCR literature, how has it evolved, and what are the conceptual similarities between its main features?

- RQ2

- What are the different levels of analysis applied by scholars in SCR? The literature has explored what should be considered individual sustainable consumption behaviors; is there any conceptual connectivity between them?

- RQ3

- What are the possible future research areas that marketing can explore within SCR to motivate individual consumers to consume more sustainably?

2. The Concept of Sustainable Consumption

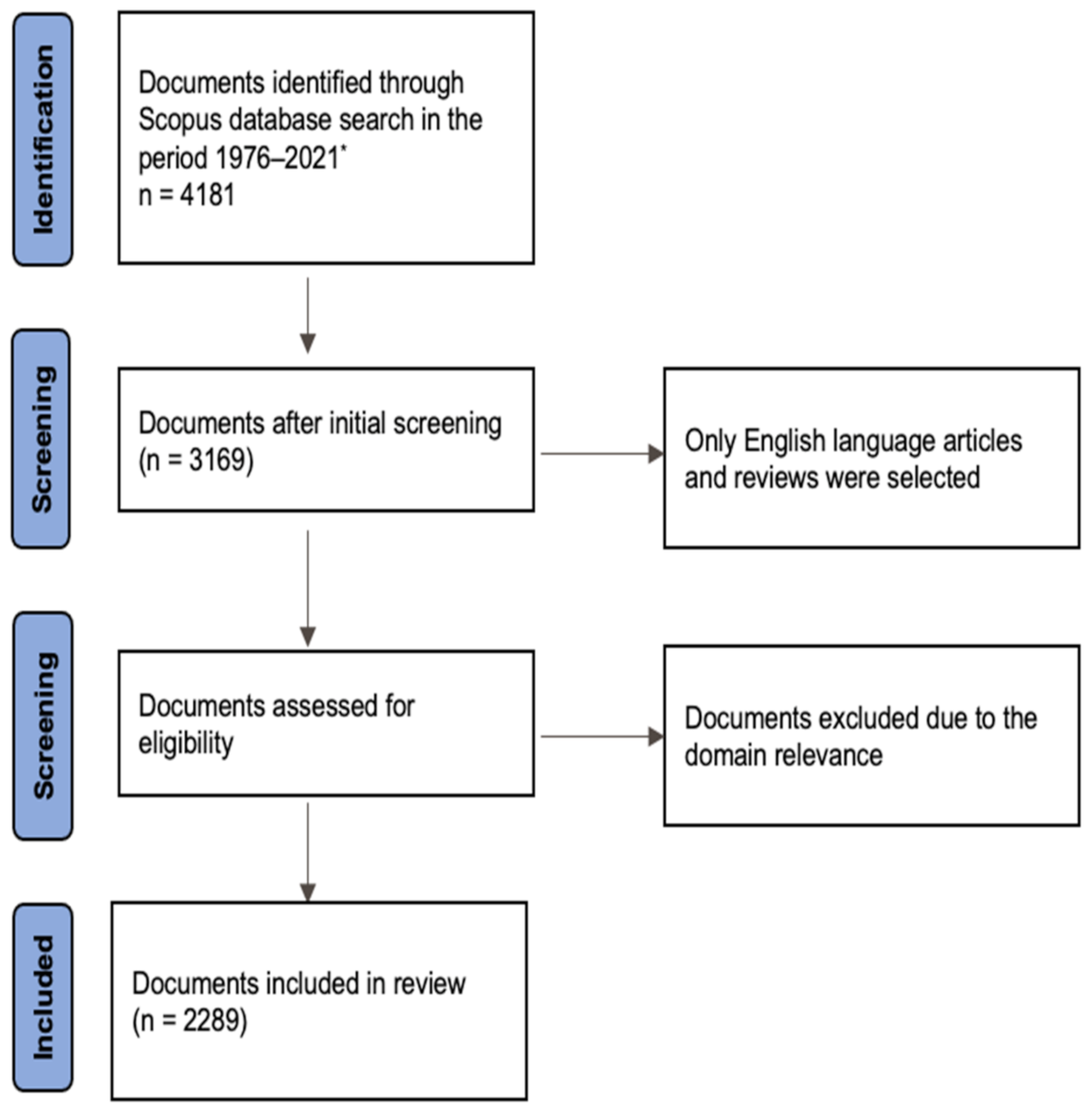

3. Methodology and Review Results

3.1. Bibliometric Review of Sustainable Consumption Research

3.1.1. Descriptive Trends

3.1.2. Bibliometric Analysis

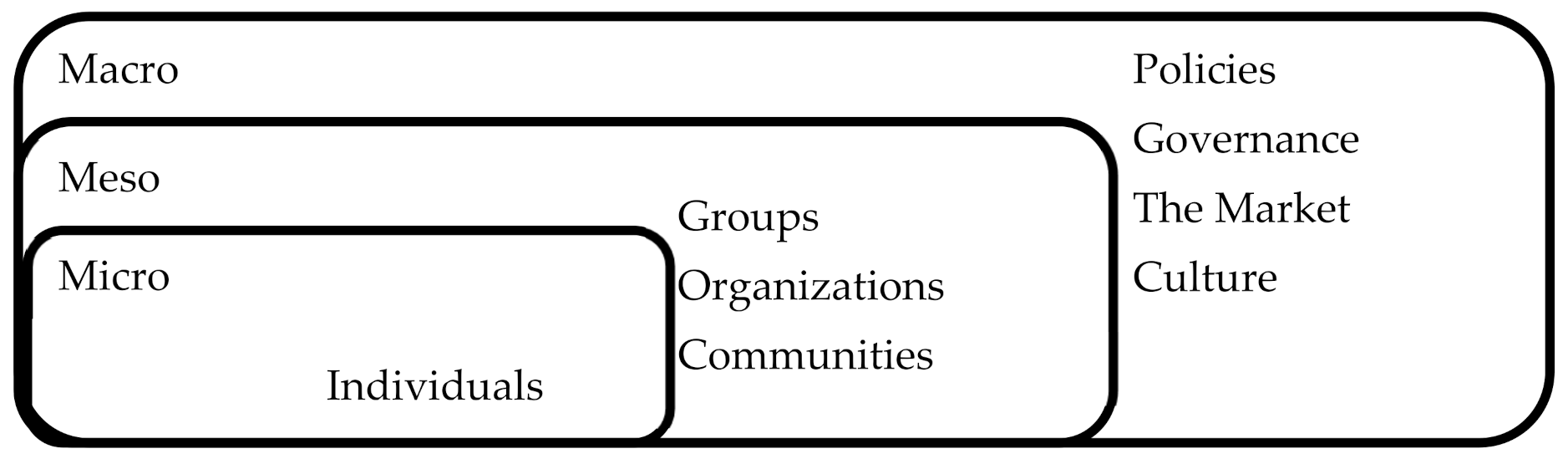

3.1.3. Three-Level Analysis

3.2. Integrative Review

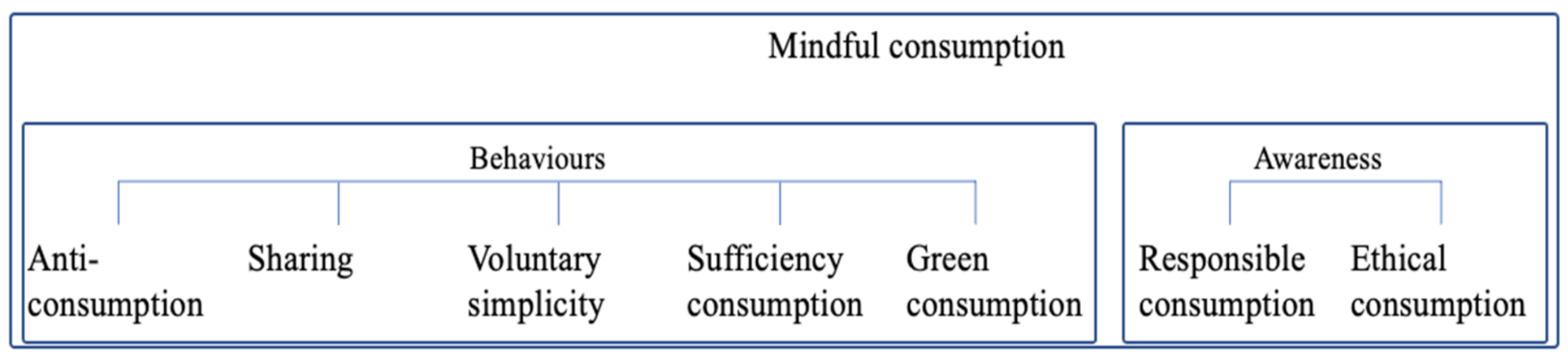

3.2.1. Micro

Responsible Consumption

Green Consumption

Ethical Consumption

Anti-Consumption

Mindful Consumption

Sharing

Sufficiency

The Mindful Mindset for All Sustainable Consumption Behaviors

3.2.2. Meso

Business Organizations

Theory of Social Practices

3.2.3. Macro

3.3. Interdependency of the Three Levels

4. Discussion

- Refine marketing fundamentals toward societal well-being as their primary goal.

- Help consumers to redefine their QOL, educating and encouraging them to undertake mindful consumption practices.

- Arrange logistics that encourage and facilitate a mindful mindset by developing products and technologies and composing rules and regulations that foster, nourish and encourage mindful consumption.

- Facilitate the movement of the mindful mindset from the micro level to the meso level and, thence, to the macro level.

5. Practical Implications

6. Limitations

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Authors | Title | Year | Contribution to Present Review | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Araújo A.C.M., Oliveira V.M., Correia S.E.N. | Sustainable consumption: Thematic evolution from 1999 to 2019 | 2021 | The search string “Sustainable consumption” |

| 2 | Testa F., Pretner G., Iovino R., Bianchi G., Tessitore S., Iraldo F. | Drivers to green consumption: a systematic review | 2021 | The search string “(green OR sustainab ∗ OR environment ∗ OR pro-environment*) AND (purchas ∗ OR consumption OR consumer ∗ OR buy*) AND (behavior ∗ OR intention*)” |

| 3 | Bălan C. 9 | How does retail engage consumers in sustainable consumption? A systematic literature review | 2021 | The search string “consumption AND (sustainable OR environmental OR green)” |

| 4 | ElHaffar G., Durif F., Dubé L. | Toward closing the attitude-intention-behavior gap in green consumption: A narrative review of the literature and an overview of future research directions | 2020 | The search string “(Environmental OR Sustainable OR Green” AND Consumption” |

| 5 | Quoquab F., Mohammad J. | A Review of Sustainable Consumption (2000 to 2020): What We Know and What We Need to Know | 2020 | 32 definitions collected from past research that will help in qualitative analysis of the literature |

| 6 | Orellano A., Valor C., Chuvieco E. | The influence of religion on sustainable consumption: A systematic review and future research agenda | 2020 | The search string “sustainable consumption” OR “green consumption” OR “ethical consumption” OR “responsible consumption” OR “pro-environmental behav*” |

| 7 | Sesini G., Castiglioni C., Lozza E. | New trends and patterns in sustainable consumption: A systematic review and research agenda | 2020 | The search string (“consumer behavio*r” OR “consumer attitude*”) AND (“sustainability” OR “sustainable consumption”) |

| 8 | Vermeir I., Weijters B., De Houwer J., Geuens M., Slabbinck H., Spruyt A., Van Kerckhove A., Van Lippevelde W., De Steur H., Verbeke W. | Environmentally Sustainable Food Consumption: A Review and Research Agenda From a Goal-Directed Perspective | 2020 | The search string “environmental sustainable,” “ecological”) AND (“consumption,” “choice”) AND (“food,” “eating”) |

| 9 | Agyeiwaah E. | Over-tourism and sustainable consumption of resources through sharing: the role of government | 2020 | The search string “sustainability, sustainable consumption” |

| 10 | Kuntsman A., Rattle I. | Towards a Paradigmatic Shift in Sustainability Studies: A Systematic Review of Peer-Reviewed Literature and Future Agenda Setting to Consider Environmental (Un)sustainability of Digital Communication | 2019 | The search string “sustainable consumption” |

| 11 | Corsini F., Laurenti R., Meinherz F., Appio F.P., Mora L. | The advent of practice theories in research on sustainable consumption: Past, current and future directions of the field | 2019 | A good reference about the application of Practice theory in SCR and how to achieve SC |

| 12 | Fischer D., Stanszus L., Geiger S., Grossman P., Schrader U. | Mindfulness and sustainable consumption: A systematic literature review of research approaches and findings | 2017 | The search string (mindful* AND (sustainab* OR environment* OR ecologic* OR ethic* OR green*) AND (consum* OR behavio*) |

| 13 | Liu Y., Qu Y., Lei Z., Jia H. | Understanding the Evolution of Sustainable Consumption Research | 2017 | The search string “Sustainable consumption” The study that was used as a foundation for the present review |

| 14 | Tripathi A., Singh M.P. | Determinants of sustainable/green consumption: A review | 2016 | The search string “SC, socially responsible consumption, environmentally responsible consumption, and green consumption” |

Appendix B

Appendix C

Appendix D

| Facets | Eco | Non-Eco | Both |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pain and discomfort (control over pain and getting relief) | x | ||

| Energy and fatigue (to perform the necessary tasks of living) | x | ||

| Sleep and rest (whether sleep is disturbed or not) | x | ||

| Positive feelings (contentment, balance, peace, happiness, hopefulness, joy, and enjoyment) | x | ||

| Thinking, learning, memory, concentration, and decision making | x | ||

| Self-esteem (person’s sense of worth as a person) | x | ||

| Body image and appearance (personal satisfaction) | x | ||

| Negative feelings (despondency, guilt, sadness, tearfulness, despair, nervousness, anxiety, and a lack of pleasure) | x | ||

| Mobility (ability to get from one place to another) | x | ||

| Activities of daily living (ability to carry out day-to-day activities) | x | ||

| Dependence on medication or treatments (physical and psychological well-being support) | x | ||

| Working capacity (ability to perform work) | x | ||

| Personal relationships (the companionship, love, and support that people desire) | x | ||

| Social support (assistance from loved ones) | x | ||

| Sexual activity (urge and desire, and express and enjoy) | x | ||

| Physical safety and security (sense of freedom) | x | ||

| Home environment (the living space and its impacts on living) | x | ||

| Financial resources (needed for a healthy and comfortable life) | x | ||

| Health and social care (availability and quality) | x | ||

| Opportunities for acquiring new information and skills (opportunity and desire) | x | ||

| Participation in and opportunities for recreation and leisure (ability, opportunities, and urge) | x | ||

| Physical environment (pollution/noise/ traffic/ climate) | x | ||

| Transport (availability and usage) | x | ||

| Spirituality/religion (personal beliefs and affect) | x |

References

- Smith, A. The Wealth of Nations: An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations; Harriman House Limited: Petersfield, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Allen, M.; Antwi-Agyei, P.; Aragon-Durand, F.; Babiker, M.; Bertoldi, P.; Bind, M.; Cartwright, A. Technical Summary: Global Warming of 1.5 °C. 2019. Available online: http://pure.iiasa.ac.at/15716 (accessed on 19 March 2022).

- Tukker, A. Leapfrogging into the future: Developing for sustainability. Int. J. Innov. Sustain. Dev. 2005, 1, 65–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stern, P.C. Toward a working definition of consumption for environmental research and policy. In Environmentally Significant Consumption: Research Directions; Stern, P.C., Dietz, T., Ruttan, V.W., Socolow, R.H., Sweeney, J., Eds.; National Academy: Washington, DC, USA, 1997; pp. 12–25. [Google Scholar]

- Fletcher, K.; Dewberry, E.; Goggin, P. Sustainable consumption by design. In Exploring Sustainable Consumption: Environmental Policy and the Social Sciences; Cohen, M.J., Murphy, J., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2001; pp. 213–224. [Google Scholar]

- The Oslo Symposium. 1994. Available online: https://enb.iisd.org/consume/oslo004.html (accessed on 19 March 2022).

- Wiek, A.; Lang, D.J. Transformational sustainability research methodology. In Sustainability Science: An introduction; Heinrichs, H., Martens, P., Michelsen, G., Wiek, A., Eds.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2016; pp. 31–41. [Google Scholar]

- Loschelder, D.D.; Siepelmeyer, H.; Fischer, D.; Rubel, J.A. Dynamic norms drive sustainable consumption: Norm-based nudging helps café customers to avoid disposable to-go-cups. J. Econ. Psychol. 2019, 75, 102146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reisch, L.A.; Cohen, M.J.; Thøgersen, J.B.; Tukker, A. Frontiers in sustainable consumption research. GAIA-Ecol. Perspect. Sci. Soc. 2016, 25, 234–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, D.; Stanszus, L.; Geiger, S.; Grossman, P.; Schrader, U. Mindfulness and sustainable consumption: A systematic literature review of research approaches and findings. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 162, 544–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Huang, D.; Liu, J.; Law, R. Which factors help visitors convert their short-term pro-environmental intentions to long-term behaviors? Int. J. Tour. Sci. 2020, 13, 33–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, H.J.; Lin, L.M. Exploring attitude-behavior gap in sustainable consumption: Comparison of recycled and upcycled fashion products. J. Bus. Res. 2013, 117, 623–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mont, O.; Plepys, A. Sustainable consumption progress: Should we be proud or alarmed? J. Clean. Prod. 2008, 16, 531–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Geneva Environment Network (GEN). Available online: www.genevaenvironmentnetwork.org/ (accessed on 19 March 2022).

- Fischer, D.; Reinermann, J.L.; Mandujano, G.G.; DesRoches, C.T.; Diddi, S.; Vergragt, P.J. Sustainable consumption communication: A review of an emerging field of research. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 300, 126880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- My, N.H.; Demont, M.; Verbeke, W. Inclusiveness of consumer access to food safety: Evidence from certified rice in Vietnam. Glob. Food Secur. 2021, 28, 100491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vermeir, I.; Verbeke, W. Sustainable food consumption: Exploring the consumer “attitude-behavioral intention” gap. J. Agric. Environ. Ethics 2006, 19, 169–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frick, V.; Matthies, E.; Thøgersen, J.; Santarius, T. Do online environments promote sufficiency or overconsumption? Online advertisement and social media effects on clothing, digital devices, and air travel consumption. J. Consum. Behav. 2021, 20, 288–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thøgersen, J.; Ölander, F. Human values and the emergence of a sustainable consumption pattern: A panel study. J. Econ. Psychol. 2002, 23, 605–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mol, A.P.; Sonnenfeld, D.A.; Spaargaren, G. The Ecological Modernisation Reader: Environmental Reform in Theory and Practice; Routledge: Oxfordshire, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Spaargaren, G. Sustainable consumption: A theoretical and environmental policy perspective. Soc. Nat. Resour. 2003, 16, 687–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prothero, A.; McDonagh, P. Ambiguity of purpose and the politics of failure: Sustainability as macromarketing’s compelling political calling. J. Marcromark. 2021, 41, 166–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiu, A.S.; Aviso, K.B.; Baquillas, J.; Tan, R.R. Can disruptive events trigger transitions towards sustainable consumption? Clean. Responsible Consum. 2020, 1, 100001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, M.J. Does the COVID-19 outbreak mark the onset of a sustainable consumption transition. Sustain. Sci. Pract. Policy 2020, 16, 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Qu, Y.; Lei, Z.; Jia, H. Understanding the evolution of sustainable consumption research. Sustain. Dev. 2017, 25, 414–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- di Giulio, A.; Fuchs, D. Sustainable consumption corridors: Concept, objections, and responses. GAIA Ecol. Perspect. Sci. Soc. 2014, 23, 184–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quoquab, F.; Mohammad, J. A review of sustainable consumption (2000 to 2020): What we know and what we need to know. J. Glob. Mark. 2020, 33, 305–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corsini, F.; Laurenti, R.; Meinherz, F.; Appio, F.P.; Mora, L. The advent of practice theories in research on sustainable consumption: Past, current and future directions of the field. Sustainability 2019, 11, 341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peattie, K. Sustainability marketing. In Handbook of Research on Sustainable Consumption; Reisch, L.A., Thogersen, J., Eds.; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2015; pp. 101–117. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, N.C.; Drumwright, M.E.; Gentile, M.C. The new marketing myopia. J. Public Policy Mark. 2010, 29, 4–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrell, O.; Hair Jr, J.F.; Marshall, G.W.; Tamilia, R.D. Understanding the history of marketing education to improve classroom instruction. Mark. Educ. Rev. 2015, 25, 159–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Key, T.M.; Clark, T.; Ferrell, O.; Stewart, D.W.; Pitt, L. Marketing’s theoretical and conceptual value proposition: Opportunities to address marketing’s influence. AMS Rev. 2020, 10, 151–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heath, M.T.P.; Chatzidakis, A. ‘Blame it on marketing’: Consumers’ views on unsustainable consumption. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2012, 36, 656–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grougiou, V.; Moschis, G.P. Antecedents of young adults’ materialistic values. J. Consum. Behav. 2015, 14, 115–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasser, T.; Ryan, R.M.; Couchman, C.E.; Sheldon, K.M. Materialistic values: Their causes and consequences. In Psychology and Consumer Culture; APA PsycBooks: Washington, DC, USA, 2004; pp. 11–28. [Google Scholar]

- Moulding, R.; Kings, C.; Knight, T. The things that make us: Self and object attachment in hoarding and compulsive buying-shopping disorder. Curr. Opin. Psychol. 2021, 39, 100–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’guinn, T.C.; Faber, R.J. Compulsive buying: A phenomenological exploration. J. Consum. Res. 1989, 16, 147–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moschis, G.P.; Mathur, A.; Shannon, R. Toward Achieving Sustainable Food Consumption: Insights from the Life Course Paradigm. Sustainability 2020, 12, 5359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Dam, Y.K.; Apeldoorn, P.A. Sustainable marketing. J. Marcromark. 1996, 16, 45–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, K.; Habib, R.; Hardisty, D.J. How to SHIFT consumer behaviors to be more sustainable: A literature review and guiding framework. J. Mark. 2019, 83, 22–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belk, R. Resurrecting marketing. AMS Rev. 2020, 10, 168–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parvatiyar, A.; Sheth, J.N. Toward an integrative theory of marketing. AMS Rev. 2021, 11, 432–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, V. Evolution of marketing as a discipline: What has happened and what to look out for. J. Mark. 2015, 79, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mordi, K.; Dixon-Ogbechi, B.; Ladipo, P. Review on The Evolution of Schools of Marketing Thought from 1980–2020. UNILAG J. Bus. 2020, 6, 35–52. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, V.; Rahman, Z.; Kazmi, A.A.; Goyal, P. Evolution of sustainability as marketing strategy: Beginning of new era. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2012, 37, 482–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morales, P.A.; True, S.; Tudor, R.K. Insights, challenges and recommendations for research on sustainability in marketing. J. Glob. Sch. Mark. Sci. 2020, 30, 394–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donthu, N.; Kumar, S.; Pattnaik, D.; Lim, W.M. A bibliometric retrospection of marketing from the lens of psychology: Insights from Psychology Marketing. Psychol. Mark. 2021, 38, 834–865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leichenko, R.; Gram-Hanssen, I.; O’Brien, K. Teaching the “how” of transformation. Sustain. Sci. 2022, 17, 573–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lunde, M.B. Sustainability in marketing: A systematic review unifying 20 years of theoretical and substantive contributions (1997–2016). AMS Rev. 2018, 8, 85–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Freitas Netto, S.V.; Sobral, M.F.F.; Ribeiro, A.R.B.; da Luz Soares, G.R. Concepts and forms of greenwashing: A systematic review. Environ. Sci. Eur. 2020, 32, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aggarwal, P.; Kadyan, A. Greenwashing: The darker side of CSR. Indian J. Appl. Res. 2014, 4, 61–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobson, K. Competing discourses of sustainable consumption: Does the’ rationalisation of lifestyles’ make sense? Environ. Politics 2002, 11, 95–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armstrong, A. Mindfulness and Consumerism: A Social Psychological Investigation. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Surrey, Guildford, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Sheth, J.N.; Sethia, N.K.; Srinivas, S. Mindful consumption: A customer-centric approach to sustainability. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2011, 39, 21–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geiger, S.M.; Grossman, P.; Schrader, U. Mindfulness and sustainability: Correlation or causation? Curr. Opin. Psychol. 2019, 28, 23–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geiger, S.M.; Fischer, D.; Schrader, U.; Grossman, P. Meditating for the planet: Effects of a mindfulness-based intervention on sustainable consumption behaviors. Environ. Behav. 2020, 52, 1012–1042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thiermann, U.B.; Sheate, W.R. The way forward in mindfulness and sustainability: A critical review and research agenda. J. Cogn. Enhanc. 2021, 5, 118–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasser, T. Living both well and sustainably: A review of the literature, with some reflections on future research, interventions and policy. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. A Math. Phys. Eng. Sci. 2017, 375, 20160369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Eck, N.J.; Waltman, L. Visualizing bibliometric networks. In Measuring Scholarly Impact; Ding, Y., Rousseau, R., Wolfram, D., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2014; pp. 285–320. [Google Scholar]

- Cronin, M.A.; George, E. The why and how of the integrative review. Organ. Res. Methods 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Souza, M.T.; da Silva, M.D.; de Carvalho, R. Integrative review: What is it? How to do it? Einstein 2010, 8, 102–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheth, J.N.; Parvatiyar, A. Sustainable marketing: Market driving, not market-driven. J. Marcromark. 2021, 41, 41,150–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snyder, H. Literature review as a research methodology: An overview and guidelines. J. Bus. Res. 2019, 104, 333–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shove, E.; Warde, A. Inconspicuous consumption: The sociology of consumption, lifestyles, and the environment. In Sociological Theory and the Environment: Classical Foundations, Contemporary Insights; Dunlap, R.E., Buttel, F.H., Dickens, P., Gijswijt, A., Eds.; Rowman & Littlefield Publishers: Lanham, MD, USA, 2002; pp. 230–251. [Google Scholar]

- Graeber, D. Consumption. Curr. Anthropol. 2011, 52, 489–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purvis, B.; Mao, Y.; Robinson, D. Three pillars of sustainability: In search of conceptual origins. Sustain. Sci. 2019, 14, 681–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, P.B. The Spirit of the Soil: Agriculture and Environmental Ethics; Routledge: Oxfordshire, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Brink, M.; Hengeveld, G.M.; Tobi, H. Interdisciplinary measurement: A systematic review of the case of sustainability. Ecol. Indic. 2020, 112, 106145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peattie, K.; Collins, A. Guest editorial: Perspectives on sustainable consumption. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2009, 33, 107–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolan, P. The Sustainability of “Sustainable Consumption”. J. Marcromark. 2002, 22, 170–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giulio, A.D.; Fischer, D.; Schäfer, M.; Blättel-Mink, B. Conceptualizing sustainable consumption: Toward an integrative framework. Sustain. Sci. Pract. Policy 2014, 10, 45–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fien, J.; Neil, C.; Bentley, M. Youth can lead the way to sustainable consumption. J. Educ. Sustain. Dev. 2008, 2, 51–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hallinger, P.; Chatpinyakoop, C. A bibliometric review of research on higher education for sustainable development, 1998–2018. Sustainability 2019, 11, 2401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Jiang, W.; Yang, Y.; Yang, Y.; Man, X. State of the art on food waste research: A bibliometrics study from 1997 to 2014. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 140, 840–846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zupic, I.; Čater, T. Bibliometric methods in management and organization. Organ. Res. Methods 2015, 18, 429–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mongeon, P.; Paul-Hus, A. The journal coverage of Web of Science and Scopus: A comparative analysis. Scientometrics 2016, 106, 213–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chabowski, B.R.; Samiee, S.; Hult, G.T.M. A bibliometric analysis of the global branding literature and a research agenda. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 2013, 44, 622–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charrois, T.L. Systematic reviews: What do you need to know to get started? Can. J. Hosp. Pharm. 2015, 68, 144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hallinger, P. A conceptual framework for systematic reviews of research in educational leadership and management. J. Educ. Adm. 2013, 51, 126–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- el Haffar, G.; Durif, F.; Dubé, L. Towards closing the attitude-intention-behavior gap in green consumption: A narrative review of the literature and an overview of future research directions. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 275, 122556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tripathi, A.; Singh, M.P. Determinants of sustainable/green consumption: A review. Int. J. Environ. Technol. Manag. 2016, 19, 316–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vermeir, I.; Weijters, B.; De Houwer, J.; Geuens, M.; Slabbinck, H.; Spruyt, A.; Verbeke, W. Environmentally sustainable food consumption: A review and research agenda from a goal-directed perspective. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 1603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agyeiwaah, E. Over-tourism and sustainable consumption of resources through sharing: The role of government. Int. J. Tour. Cities 2019, 6, 99–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bălan, C. How Does Retail Engage Consumers in Sustainable Consumption? A Systematic Literature Review. Sustainability 2021, 13, 96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuntsman, A.; Rattle, I. Towards a paradigmatic shift in sustainability studies: A systematic review of peer reviewed literature and future agenda setting to consider environmental (Un) sustainability of digital communication. Environ. Commun. 2019, 13, 567–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orellano, A.; Valor, C.; Chuvieco, E. The influence of religion on sustainable consumption: A systematic review and future research agenda. Sustainability 2020, 12, 7901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sesini, G.; Castiglioni, C.; Lozza, E. New trends and patterns in sustainable consumption: A systematic review and research agenda. Sustainability 2020, 12, 5935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Testa, F.; Pretner, G.; Iovino, R.; Bianchi, G.; Tessitore, S.; Iraldo, F. Drivers to green consumption: A systematic review. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2021, 23, 4826–4880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araújo, A.; Oliveira, V.M.; Correia, S.E. Sustainable Consumption: Thematic Evolution from 1999 to 2019. Rev. Adm. Mackenzie 2021, 22, 1–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J.; Altman, D.G.; Group, P. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. Ann. Intern. Med. 2009, 151, 264–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, H.D.; McCain, K.W. Visualizing a discipline: An author co-citation analysis of information science, 1972–1995. J. Am. Soc. Inf. Sci. 1998, 49, 327–355. [Google Scholar]

- Shafique, M. Thinking inside the box? Intellectual structure of the knowledge base of innovation research (1988–2008). Strateg. Manag. J. 2013, 34, 62–93. [Google Scholar]

- Jackson, T. Live better by consuming less?: Is there a “double dividend” in sustainable consumption? J. Ind. Ecol. 2005, 9, 19–36. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.; Wei, L.; Zeng, X.; Zhu, J. Mindfulness in ethical consumption: The mediating roles of connectedness to nature and self-control. Int. Mark. Rev. 2021, 38, 756–779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. The theory of planned behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Processes 1991, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parajuly, K.; Fitzpatrick, C.; Muldoon, O.; Kuehr, R. Behavioral change for the circular economy: A review with focus on electronic waste management in the EU. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. X 2020, 6, 100035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thøgersen, J.; de Barcellos, M.D.; Perin, M.G.; Zhou, Y. Consumer buying motives and attitudes towards organic food in two emerging markets: China and Brazil. Int. Mark. Rev. 2015, 32, 389–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vermeir, I.; Verbeke, W. Sustainable food consumption among young adults in Belgium: Theory of planned behaviour and the role of confidence and values. Ecol. Econ. 2008, 64, 542–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nijhuis, M. Nudging Tourists: The Application of Nudging within Tourism to Achieve Sustainable Travelling. Master’s Thesis, University of Twente, Enschede, The Netherlands, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Ölander, F.; Thøgersen, J. Informing versus nudging in environmental policy. J. Consum. Policy 2014, 37, 341–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, S.H. An overview of the Schwartz theory of basic values. Online Read. Psychol. Cult. 2012, 2, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, S.H.; Sortheix, F. Values and subjective well-being. In Handbook of Well-Being; DEF Publishers: Salt Lake City, UT, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Stern, P.C.; Dietz, T.; Abel, T.; Guagnano, G.A.; Kalof, L. A value-belief-norm theory of support for social movements: The case of environmentalism. Hum. Ecol. Rev. 1999, 6, 81–97. [Google Scholar]

- Stern, P.C. Toward a coherent theory of environmentally significant behavior. J. Soc. Issues 2000, 56, 407–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robles-Avila, S.E. The Role of Environmental Personal Norms in the VBN Framework: Testing the Differences between the United States and Mexico regarding the Disposal of Potentially Harmful Products. J. Int. Consum. Mark. 2021, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, R.; Jha, M. Values influencing sustainable consumption behaviour: Exploring the contextual relationship. J. Bus. Res. 2017, 76, 77–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steg, L.; Dreijerink, L.; Abrahamse, W. Factors influencing the acceptability of energy policies: A test of VBN theory. J. Environ. Psychol. 2005, 25, 415–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peattie, K. Green consumption: Behavior and norms. Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour. 2010, 35, 195–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, J.A. Profiling levels of socially responsible consumer behavior: A cluster analytic approach and its implications for marketing. J. Mark. Theory Pract. 1995, 3, 97–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, J.A. Green consumers in the 1990s: Profile and implications for advertising. J. Bus. Res. 1996, 36, 217–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thøgersen, J. Transport-related lifestyle and environmentally-friendly travel mode choices: A multi-level approach. Transp. Res. Part A Policy Pract. 2018, 107, 166–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, W.; Hwang, K.; McDonald, S.; Oates, C.J. Sustainable consumption: Green consumer behaviour when purchasing products. Sustain. Dev. 2010, 18, 20–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dickinson, R.A.; Carsky, M.L. The consumer as economic voter. In The Ethical Consumer; SAGE Publications Ltd.: Newbury Park, CA, USA, 2005; pp. 25–36. [Google Scholar]

- Hansen, U.; Schrader, U. A modern model of consumption for a sustainable society. J. Consum. Policy 1997, 20, 443–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newholm, T.; Shaw, D. Studying the ethical consumer: A review of research. J. Consum. Behav. 2007, 6, 253–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaw, D.; Grehan, E.; Shiu, E.; Hassan, L.; Thomson, J. An exploration of values in ethical consumer decision making. J. Consum. Behav. Int. Res. Rev. 2005, 4, 185–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillipov, M.; Gale, F. Celebrity chefs, consumption politics and food labelling: Exploring the contradictions. J. Consum. Cult. 2020, 20, 400–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Black, I.R.; Cherrier, H. Anti-consumption as part of living a sustainable lifestyle: Daily practices, contextual motivations and subjective values. J. Consum. Behav. 2010, 9, 437–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexander, S.; Ussher, S. The voluntary simplicity movement: A multi-national survey analysis in theoretical context. J. Consum. Cult. 2012, 12, 66–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatanaka, M. Beyond consuming ethically? Food citizens, governance, and sustainability. J. Rural. Stud. 2020, 77, 55–62. [Google Scholar]

- Tosun, P.; Sezgin, S. Voluntary simplicity: A content analysis of consumer comments. J. Consum. Mark. 2021, 38, 484–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.A. Theory of Consumer Behavior: An Islamic Perspective; MPRA Paper No. 104208; Munich Personal RePEc Archive: Munich, Germany, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Barnett, C.; Clarke, N.; Cloke, P.; Malpass, A. The political ethics of consumerism. Consum. Policy Rev. 2005, 15, 45–51. [Google Scholar]

- Barnett, C.; Clarke, N.; Cloke, P. Whatever happened to ethical consumption? J. Consum. Ethics 2017, 1, 5–11. [Google Scholar]

- Warde, A. Consumption and theories of practice. J. Consum. Culture 2005, 5, 131–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barr, S.; Gilg, A.W.; Ford, N. The household energy gap: Examining the divide between habitual-and purchase-related conservation behaviours. Energy Policy 2005, 33, 1425–1444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarke, N.; Cloke, P.; Barnett, C.; Malpass, A. The spaces and ethics of organic food. J. Rural. Stud. 2008, 24, 219–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adger, W.N.; Brown, K.; Fairbrass, J.; Jordan, A.; Paavola, J.; Rosendo, S.; Seyfang, G. Governance for sustainability: Towards a ‘thick’ analysis of environmental decisionmaking. Environ. Plan. A 2003, 35, 1095–1110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, D. Beyond the throwaway society: Ordinary domestic practice and a sociological approach to household food waste. Sociology 2012, 46, 41–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shove, E. Converging conventions of comfort, cleanliness and convenience. J. Consum. Policy 2003, 26, 395–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spaargaren, G. Theories of practices: Agency, technology, and culture: Exploring the relevance of practice theories for the governance of sustainable consumption practices in the new world-order. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2011, 21, 813–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spaargaren, G.; Cohen, M.J. Greening lifecycles and lifestyles: Sociotechnical innovations in consumption and production as core concerns of ecological modernisation theory. In The Ecological Modernisation Reader; Routledge: Oxfordshire, UK, 2020; pp. 257–274. [Google Scholar]

- Jepperson, R.; Meyer, J.W. Multiple levels of analysis and the limitations of methodological individualisms. Sociol. Theory 2011, 29, 54–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serpa, S.; Ferreira, C.M. Micro, meso and macro levels of social analysis. Int. J. Soc. Sci. Stud. 2019, 7, 120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belk, R.W.; Eckhardt, G.M.; Bardhi, F. Introduction to the Handbook of the Sharing Economy: The paradox of the sharing economy. In Handbook of the Sharing Economy; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Makkar, M.; Yap, S.-F.; Belk, R. Stabilising collaborative consumer networks: How technological mediation shapes relational work. Eur. J. Mark. 2021, 55, 1385–1410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Middlemiss, L. The effects of community-based action for sustainability on participants’ lifestyles. Local Environ. 2011, 16, 265–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thøgersen, J. How may consumer policy empower consumers for sustainable lifestyles? J. Consum. Policy 2005, 28, 143–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tukker, A.; Cohen, M.J.; Hubacek, K.; Mont, O. The impacts of household consumption and options for change. J. Ind. Ecol. 2010, 14, 13–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lenzen, M.; Peters, G.M. How city dwellers affect their resource hinterland: A spatial impact study of Australian households. J. Ind. Ecol. 2010, 14, 73–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lenzen, M.; Sun, Y.-Y.; Faturay, F.; Ting, Y.-P.; Geschke, A.; Malik, A. Author Correction: The carbon footprint of global tourism. Nat. Clim. Chang. 2018, 8, 544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiedmann, T.O.; Schandl, H.; Lenzen, M.; Moran, D.; Suh, S.; West, J.; Kanemoto, K. The material footprint of nations. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2015, 112, 6271–6276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, T.; Webster, R. Limits to Growth revisited. Reframing Global Social Policy: Social Investment for Sustainable and Inclusive Growth; Policy Press: Bristol, UK, 2017; p. 295. [Google Scholar]

- Lorek, S.; Spangenberg, J.H. Sustainable consumption within a sustainable economy-beyond green growth and green economies. J. Clean. Prod. 2014, 63, 33–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soper, K. Rethinking the “good life”: The consumer as citizen. Capital. Nat. Soc. 2004, 15, 111–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reisch, L.; Eberle, U.; Lorek, S. Sustainable food consumption: An overview of contemporary issues and policies. Sustain. Sci. Pract. Policy 2013, 9, 7–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seyfang, G. The new economics of sustainable consumption. In Minería Transnacional, Narrativas del Desarrollo y Resistencias Sociales; Biblos: Buenos Aires, Argentina, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Kilbourne, W.; McDonagh, P.; Prothero, A. Sustainable consumption and the quality of life: A macromarketing challenge to the dominant social paradigm. J. Macromark. 1997, 17, 4–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, L.M.; Shiu, E.; Shaw, D. Who says there is an intention-behaviour gap? Assessing the empirical evidence of an intention-behaviour gap in ethical consumption. J. Bus. Ethics 2016, 136, 219–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pepper, M.; Jackson, T.; Uzzell, D. An examination of the values that motivate socially conscious and frugal consumer behaviours. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2009, 33, 126–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, T. Prosperity without Growth: Foundations for the Economy of Tomorrow; Taylor Francis: Abingdon, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Blue, S.; Shove, E.; Carmona, C.; Kelly, M.P. Theories of practice and public health: Understanding (un) healthy practices. Crit. Public Health 2016, 26, 36–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thøgersen, J.; Haugaard, P.; Olesen, A. Consumer responses to ecolabels. Eur. J. Mark. 2010, 44, 1787–1810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steg, L.; Bolderdijk, J.W.; Keizer, K.; Perlaviciute, G. An integrated framework for encouraging pro-environmental behaviour: The role of values, situational factors and goals. J. Environ. Psychol. 2014, 38, 104–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steg, L. Promoting household energy conservation. Energy Policy 2008, 36, 4449–4453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connolly, J.; Prothero, A. Green consumption: Life-politics, risk and contradictions. J. Consum. Cult. 2008, 8, 117–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrigan, M.; Lazell, J.; Bosangit, C.; Magrizos, S. Burgers for tourists who give a damn! Driving disruptive social change upstream and downstream in the tourist food supply chain. J. Sustain. Tour. 2017, 25, 1563–1582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrigan, M.; Moraes, C.; Leek, S. Fostering responsible communities: A community social marketing approach to sustainable living. J. Bus. Ethics 2011, 100, 515–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belk, R.; Llamas, R. The nature and effects of sharing in consumer behavior. In Transformative Consumer Research for Personal and Collective Well-Being; Routledge: Oxfordshire, UK, 2012; pp. 653–674. [Google Scholar]

- Shaw, D.; Newholm, T.; Dickinson, R. Consumption as voting: An exploration of consumer empowerment. Eur. J. Mark. 2006, 40, 1049–1067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnett, C.; Cafaro, P.; Newholm, T. Philosophy and Ethical Consumption; Sage Publications Ltd.: London, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Warde, A. After taste: Culture, consumption and theories of practice. J. Consum. Cult. 2014, 14, 279–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thyroff, A.; Kilbourne, W.E. Self-enhancement and individual competitiveness as mediators in the materialism/consumer satisfaction relationship. J. Bus. Res. 2018, 92, 189–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fraanje, W.; Spaargaren, G. What future for collaborative consumption? A practice theoretical account. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 208, 499–508. [Google Scholar]

- Spangenberg, J.H.; Lorek, S. Sufficiency and consumer behaviour: From theory to policy. Energy Policy 2019, 129, 1070–1079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandler, J.D.; Vargo, S.L. Contextualization and value-in-context: How context frames exchange. Mark. Theory 2011, 11, 35–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunt, S. Marketing Theory: Conceptual Foundations of Research in Marketing; Grid: Boston, MA, USA, 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Belter, C.W. Bibliometric indicators: Opportunities and limits. J. Med. Libr. Assoc. 2015, 103, 219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vlados, C.; Chatzinikolaou, D. Macro, meso, and micro policies for strengthening entrepreneurship: Towards an integrated competitiveness policy. J. Bus. Econ. Policy 2020, 7, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antonetti, P.; Maklan, S. Feelings that make a difference: How guilt and pride convince consumers of the effectiveness of sustainable consumption choices. J. Bus. Ethics 2014, 124, 117–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doran, C.J. The role of personal values in fair trade consumption. J. Bus. Ethics 2009, 84, 549–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moser, A.K. Thinking green, buying green? Drivers of pro-environmental purchasing behavior. J. Consum. Mark. 2015, 32, 167–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barr, S.; Gilg, A.; Shaw, G. Promoting Sustainable Lifestyles: A Social Marketing Approach—Final Summary Report; University of Exeter: Exeter, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- De Bernardi, P.; Tirabeni, L. Alternative food networks: Sustainable business models for anti-consumption food cultures. Br. Food J. 2018, 120, 1776–1791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peattie, K.; Peattie, S.; Ponting, C. Climate change: A social and commercial marketing communications challenge. EuroMed J. Bus. 2009, 4, 270–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soper, K. Alternative hedonism, cultural theory and the role of aesthetic revisioning. In Cultural Studies and Anti-Consumerism; Routledge: Oxfordshire, UK, 2014; pp. 59–79. [Google Scholar]

- Spaargaren, G.; Mol, A.P. Greening global consumption: Redefining politics and authority. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2008, 18, 350–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duscha, V.; Denishchenkova, A.; Wachsmuth, J. Achievability of the Paris Agreement targets in the EU: Demand-side reduction potentials in a carbon budget perspective. Clim. Policy 2019, 19, 161–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorek, S.; Fuchs, D. Strong sustainable consumption governance-precondition for a degrowth path? J. Clean. Prod. 2013, 38, 36–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webster, F.E., Jr. Determining the characteristics of the socially conscious consumer. J. Consum. Res. 1975, 2, 188–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisk, G. Criteria for a theory of responsible consumption. J. Mark. 1973, 37, 24–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrington, M.; Chatzidakis, A.; Goworek, H.; Shaw, D. Consumption ethics: A review and analysis of future directions for interdisciplinary research. J. Bus. Ethics 2021, 168, 215–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, S.; Agrawal, R. Environmentally responsible consumption: Construct definition, scale development, and validation. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2018, 25, 523–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, J.; She, Q. Developing a trichotomy model to measure socially responsible behaviour in China. Int. J. Mark. Res. 2011, 53, 253–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paek, H.-J.; Nelson, M.R. To buy or not to buy: Determinants of socially responsible consumer behavior and consumer reactions to cause-related and boycotting ads. J. Curr. Issues Res. Advert. 2009, 31, 75–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olson, E.L. It’s not easy being green: The effects of attribute tradeoffs on green product preference and choice. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2013, 41, 171–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adomaviciute, K. Relationship between utilitarian and hedonic consumer behavior and socially responsible consumption. Econ. Manag. 2013, 18, 754–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Elkington, J.; Hailes, J. The Green Consumer Guide; Penguin: Ringwood, Australia, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, L.; Bock, D.; Joseph, M. Green marketing: What the Millennials buy. J. Bus. Strategy 2013, 34, 3–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Semprebon, E.; Mantovani, D.; Demczuk, R.; Maior, C.S.; Vilasanti, V. Green consumption: A network analysis in marketing. Mark. Intell. Plan. 2018, 37, 18–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peattie, K. Towards sustainability: The third age of green marketing. Mark. Rev. 2001, 2, 129–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polonsky, M.J. An introduction to green marketing. Electron. Green J. 1994, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connolly, J.; Prothero, A. Sustainable consumption: Consumption, consumers and the commodity discourse. Consum. Mark. Cult. 2003, 6, 275–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Z.-H.; Chang, C.-T.; Lee, Y.-K. Linking hedonic and utilitarian shopping values to consumer skepticism and green consumption: The roles of environmental involvement and locus of control. Rev. Manag. Sci. 2020, 14, 61–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nyilasy, G.; Gangadharbatla, H.; Paladino, A. Perceived greenwashing: The interactive effects of green advertising and corporate environmental performance on consumer reactions. J. Bus. Ethics 2014, 125, 693–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muldoon, A. Where the green is: Examining the paradox of environmentally conscious consumption. Electron. Green J. 2006, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klein, J.G.; Smith, N.C.; John, A. Why we boycott: Consumer motivations for boycott participation. J. Mark. 2004, 68, 92–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Fernández, A.M. Price sensitivity versus ethical consumption: A study of millennial utilitarian consumer behavior. J. Mark. Anal. 2020, 8, 57–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper-Martin, E.; Holbrook, M.B. Ethical consumption experiences and ethical space. ACR N. Am. Adv. 1993, 20, 113–118. [Google Scholar]

- Griffiths, P. Marketing by controlling social discourse: The fairtrade case. Econ. Aff. 2015, 35, 256–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber, J. Fair trade coffee enthusiasts should confront reality. Cato J. 2007, 27, 109. [Google Scholar]

- Chatzidakis, A.; Lee, M.S. Anti-consumption as the study of reasons against. J. Marcromark. 2013, 33, 190–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffmann, S.; Müller, S. Consumer boycotts due to factory relocation. J. Bus. Res. 2009, 62, 239–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cherrier, H. Anti-consumption discourses and consumer-resistant identities. J. Bus. Res. 2009, 62, 181–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lastovicka, J.L.; Bettencourt, L.A.; Hughner, R.S.; Kuntze, R.J. Lifestyle of the tight and frugal: Theory and measurement. J. Consum. Res. 1999, 26, 85–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Philp, M.; Nepomuceno, M.V. When the frugal become wasteful: An examination into how impression management can initiate the end-stages of consumption for frugal consumers. Psychol. Mark. 2020, 37, 326–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujii, S. Environmental concern, attitude toward frugality, and ease of behavior as determinants of pro-environmental behavior intentions. J. Environ. Psychol. 2006, 26, 262–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, D. Thrifty, green or frugal: Reflections on sustainable consumption in a changing economic climate. Geoforum 2011, 42, 550–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chowdhury, R.M. Religiosity and voluntary simplicity: The mediating role of spiritual well-being. J. Bus. Ethics 2018, 152, 149–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Ma, B.; Bai, R.; Zhang, L. The unexpected effect of frugality on green purchase intention. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2021, 59, 102385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iyer, R.; Muncy, J.A. Purpose and object of anti-consumption. J. Bus. Res. 2009, 62, 160–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDonald, S.; Oates, C.J.; Young, C.W.; Hwang, K. Toward sustainable consumption: Researching voluntary simplifiers. Psychol. Mark. 2006, 23, 515–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rich, S.A.; Hanna, S.; Wright, B.J. Simply satisfied: The role of psychological need satisfaction in the life satisfaction of voluntary simplifiers. J. Happiness Stud. 2017, 18, 89–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huneke, M.E. The face of the un-consumer: An empirical examination of the practice of voluntary simplicity in the United States. Psychol. Mark. 2005, 22, 527–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kala, L.; Galčanová, L.; Pelikán, V. Narratives and practices of voluntary simplicity in the Czech post-socialist context. Czech Sociol. Rev. 2017, 53, 833–855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elgin, D.; Mitchell, A. Voluntary simplicity. In Planning Review; William Morrow: New York, NY, USA, 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, K.W.; Ryan, R.M. The benefits of being present: Mindfulness and its role in psychological well-being. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2003, 84, 822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bishop, S.R.; Lau, M.; Shapiro, S.; Carlson, L.; Anderson, N.D.; Carmody, J.; Velting, D. Mindfulness: A proposed operational definition. Clin. Psychol. Sci. Pract. 2004, 11, 230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carson, S.H.; Langer, E.J. Mindfulness and self-acceptance. J. Ration. Emot. Cogn. Behav. Ther. 2006, 24, 29–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grossman, P.; Kappos, L.; Gensicke, H.; D’Souza, M.; Mohr, D.C.; Penner, I.K.; Steiner, C. MS quality of life, depression, and fatigue improve after mindfulness training: A randomized trial. Neurology 2010, 75, 1141–1149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosenberg, E.L. Mindfulness and consumerism. In Psychology and Consumer Culture: The Struggle for a Good Life in a Materialistic World; Kasser, T., Kanner, A.D., Eds.; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2004; pp. 107–125. [Google Scholar]

- Schuman-Olivier, Z.; Trombka, M.; Lovas, D.A.; Brewer, J.A.; Vago, D.R.; Gawande, R.; Fulwiler, C. Mindfulness and behavior change. Harv. Rev. Psychiatry 2020, 28, 371–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Condon, P. Mindfulness, compassion, and prosocial behaviour. In Mindfulness in Social Psychology; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2017; pp. 124–138. [Google Scholar]

- Grossman, P. Mindfulness: Awareness informed by an embodied ethic. Mindfulness 2015, 6, 17–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galante, J.; Friedrich, C.; Dawson, A.F.; Modrego-Alarcón, M.; Gebbing, P.; Delgado-Suárez, I.; Jones, P.B. Mindfulness-based programmes for mental health promotion in adults in nonclinical settings: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. PLoS Med. 2021, 18, e1003481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hurst, M.; Dittmar, H.; Bond, R.; Kasser, T. The relationship between materialistic values and environmental attitudes and behaviors: A meta-analysis. J. Environ. Psychol. 2013, 36, 257–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruffault, A.; Bernier, M.; Juge, N.; Fournier, J.F. Mindfulness may moderate the relationship between intrinsic motivation and physical activity: A cross-sectional study. Mindfulness 2016, 7, 445–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baer, R.A. Mindfulness training as a clinical intervention: A conceptual and empirical review. Clin. Psychol. Sci. Pract. 2003, 10, 125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grube, J.W.; Mayton, D.M.; Ball-Rokeach, S.J. Inducing change in values, attitudes, and behaviors: Belief system theory and the method of value self-confrontation. J. Soc. Issues 1994, 50, 153–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sajjad, A.; Shahbaz, W. Mindfulness and Social Sustainability: An Integrative Review. Soc. Indic. Res. 2020, 150, 73–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wamsler, C.; Brossmann, J.; Hendersson, H.; Kristjansdottir, R.; McDonald, C.; Scarampi, P. Mindfulness in sustainability science, practice, and teaching. Sustain. Sci. 2018, 13, 143–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimidjian, S.; Linehan, M.M. Defining an agenda for future research on the clinical application of mindfulness practice. Clin. Psychol. Sci. Pract. 2003, 10, 166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assadourian, E. Global Economic Growth Continues at Expense of Ecological Systems; Worldwatch Institute: Washington, DC, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Benett, A.; O’Reilly, A. Consumed: Rethinking Business in the Era of Mindful Spending; Macmillan: New York, NY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Berthon, P.; Pitt, L.; Campbell, C. Addictive devices: A public policy analysis of sources and solutions to digital addiction. J. Public Policy Mark. 2019, 38, 451–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bronner, F.; de Hoog, R. Conspicuous consumption and the rising importance of experiential purchases. Int. J. Mark. Res. 2018, 60, 88–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahl, S.; Milne, G.R.; Ross, S.M.; Mick, D.G.; Grier, S.A.; Chugani, S.K.; Dorsey, J.D. Mindfulness: Its transformative potential for consumer, societal, and environmental well-being. J. Public Policy Mark. 2016, 35, 198–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belk, R.W. Ownership, Ego and Sharing. In Proceedings of the Conference to Buy or to Rent, Paris, France, 26–27 January 2006; ESCP-EAP: Paris, France, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Belk, R. Sharing. J. Consum. Res. 2010, 36, 715–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yates, L. Sharing, households and sustainable consumption. J. Consum. Cult. 2018, 18, 433–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bardhi, F.; Eckhardt, G.M. Access-based consumption: The case of car sharing. J. Consum. Res. 2012, 39, 881–898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, C.J. The sharing economy: A pathway to sustainability or a nightmarish form of neoliberal capitalism? Ecol. Econ. 2016, 121, 149–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mongsawad, P. The philosophy of the sufficiency economy: A contribution to the theory of development. Asia Pac. Dev. J. 2010, 17, 123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNDP Thailand. Thailand Human Development Report 2007—Sufficiency Economy and Human Development; UNDP Thailand: Bangkok, Thailand, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Heinrichs, H. Sharing economy: A potential new pathway to sustainability. GAIA Ecol. Perspect. Sci. Soc. 2013, 22, 228–231. [Google Scholar]

- Hossain, M. Sharing economy: A comprehensive literature review. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2020, 87, 102470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuchs, D.A.; Lorek, S. Sustainable consumption governance: A history of promises and failures. J. Consum. Policy 2005, 28, 261–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, T. Slower consumption reflections on product life spans and the “throwaway society”. J. Ind. Ecol. 2005, 9, 51–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gossen, M.; Ziesemer, F.; Schrader, U. Why and how commercial marketing should promote sufficient consumption: A systematic literature review. J. Marcromark. 2019, 39, 252–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spengler, L. Two types of ‘enough’: Sufficiency as minimum and maximum. Environ. Politics 2016, 25, 921–940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorge, H.; Herbert, M.; Özçağlar-Toulouse, N.; Robert, I. What do we really need? Questioning consumption through sufficiency. J. Marcromark. 2015, 35, 11–22. [Google Scholar]

- Sandberg, M. Sufficiency transitions: A review of consumption changes for environmental sustainability. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 293, 126097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheth, J. The future history of consumer research: Will the discipline rise to the opportunity? In ACR North American Advances; University of Minnesota: Duluth, MN, USA, 2017; Volume 45. [Google Scholar]

- Lim, W.M. Inside the sustainable consumption theoretical toolbox: Critical concepts for sustainability, consumption, and marketing. J. Bus. Res. 2017, 78, 69–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schenk, N.J.; Moll, H.C.; Uiterkamp, A.J.S. Meso-level analysis, the missing link in energy strategies. Energy Policy 2007, 35, 1505–1516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaspal, R.; Carriere, K.R.; Moghaddam, F.M. Bridging micro, meso, and macro processes in social psychology. In Psychology as the Science of Human Being; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2016; pp. 265–276. [Google Scholar]

- Spaargaren, G.; van Koppen, C.K. Provider strategies and the greening of consumption practices: Exploring the role of companies in sustainable consumption. In The New Middle Classes; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2009; pp. 265–276. [Google Scholar]

- Niccolucci, V.; Botto, S.; Rugani, B.; Nicolardi, V.; Bastianoni, S.; Gaggi, C. The real water consumption behind drinking water: The case of Italy. J. Environ. Manag. 2011, 92, 2611–2618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotler, P. Reinventing marketing to manage the environmental imperative. J. Mark. 2011, 75, 132–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spaargaren, G.; Oosterveer, P.; Loeber, A. Sustainability transitions in food consumption, retail and production. In Food Practices in Transition; Routledge: Oxfordshire, UK, 2013; pp. 21–52. [Google Scholar]

- Fine, B.; Heasman, M.; Wright, J. Consumption in the Age of Affluence: The World of Food. Routledge: Oxfordshire, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Thongplew, N.; Kotlakome, R. Getting a drink: An experiment for enabling a sustainable practice in Thai university settings. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 218, 294–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acemoglu, D.; Akcigit, U.; Hanley, D.; Kerr, W. Transition to clean technology. J. Political Econ. 2016, 124, 52–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bera, A.; Sadowska, B. Clean production as an element of sustainable development. In Sustainable Production: Novel Trends in Energy 2020, Environment and Material Systems; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2020; pp. 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Janssen, M.A.; Jager, W. Stimulating diffusion of green products. J. Evol. Econ. 2002, 12, 283–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sammer, K.; Wüstenhagen, R. The influence of eco-labelling on consumer behaviour—Results of a discrete choice analysis for washing machines. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2006, 15, 185–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urbaniec, M.; Sołtysik, M.; Prusak, A.; Kułakowski, K.; Wojnarowska, M. Fostering sustainable entrepreneurship by business strategies: An explorative approach in the bioeconomy. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2021, 31, 251–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowen, H.R. Graduate education in economics. Am. Econ. Rev. 1953, 43, iv-223. [Google Scholar]

- Carroll, A.B. Corporate social responsibility: Evolution of a definitional construct. Bus. Soc. 1999, 38, 268–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teneta-Skwiercz, D. Eco-labeling as a Tool to Implement the Concept of Corporate Social Responsibility: The Results of a Pilot Study. In Finance and Sustainability; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2020; pp. 323–333. [Google Scholar]

- Dendler, L. Sustainability meta labelling: An effective measure to facilitate more sustainable consumption and production? J. Clean. Prod. 2014, 63, 74–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taufique, K.M.R.; Polonsky, M.J.; Vocino, A.; Siwar, C. Measuring consumer understanding and perception of eco-labelling: Item selection and scale validation. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2019, 43, 298–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koos, S. Varieties of environmental labelling, market structures, and sustainable consumption across Europe: A comparative analysis of organizational and market supply determinants of environmental-labelled goods. J. Consum. Policy 2011, 34, 127–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yokessa, M.; Marette, S. A review of eco-labels and their economic impact. Int. Rev. Environ. Resour. Econ. 2019, 13, 119–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Codagnone, C.; Veltri, G.A.; Bogliacino, F.; Lupiáñez-Villanueva, F.; Gaskell, G.; Ivchenko, A.; Mureddu, F. Labels as nudges? An experimental study of car eco-labels. Econ. Politica 2016, 33, 403–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carroll, A.B. Carroll’s pyramid of CSR: Taking another look. Int. J. Corp. Soc. Responsib. 2016, 1, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Souza, C. Ecolabel programmes: A stakeholder (consumer) perspective. Corp. Commun. Int. J. 2004, 9, 179–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamali, D. A stakeholder approach to corporate social responsibility: A fresh perspective into theory and practice. J. Bus. Ethics 2008, 82, 213–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afsar, B.; Cheema, S.; Javed, F. Activating employee’s pro-environmental behaviors: The role of CSR, organizational identification, and environmentally specific servant leadership. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2018, 25, 904–911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rashid, N.R.N.A.; Khalid, S.A.; Rahman, N.I.A. Environmental corporate social responsibility (ECSR): Exploring its influence on customer loyalty. Procedia Econ. Financ. 2015, 31, 705–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delmas, M.A.; Burbano, V.C. The drivers of greenwashing. Calif. Manag. Rev. 2011, 54, 64–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyon, T.P.; Montgomery, A.W. The means and end of greenwash. Organ. Environ. 2015, 28, 223–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velte, P. Do CEO incentives and characteristics influence corporate social responsibility (CSR) and vice versa? A literature Review. Soc. Responsib. J. 2019, 16, 1293–1323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrenko, O.V.; Aime, F.; Ridge, J.; Hill, A. Corporate social responsibility or CEO narcissism? CSR motivations and organizational performance. Strateg. Manag. J. 2016, 37, 262–279. [Google Scholar]

- Ghisellini, P.; Cialani, C.; Ulgiati, S. A review on circular economy: The expected transition to a balanced interplay of environmental and economic systems. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 114, 11–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henry, M.; Schraven, D.; Bocken, N.; Frenken, K.; Hekkert, M.; Kirchherr, J. The battle of the buzzwords: A comparative review of the circular economy and the sharing economy concepts. Environ. Innov. Soc. Transit. 2021, 38, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bocken, N.M.; Short, S.W.; Rana, P.; Evans, S. A literature and practice review to develop sustainable business model archetypes. J. Clean. Prod. 2014, 65, 42–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maitre-Ekern, E.; Dalhammar, C. Towards a hierarchy of consumption behaviour in the circular economy. Maastricht J. Eur. Comp. Law 2019, 26, 394–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singhal, D.; Tripathy, S.; Jena, S.K. Remanufacturing for the circular economy: Study and evaluation of critical factors. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2020, 156, 104681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allwood, J.M.; Cullen, J.M.; Carruth, M.A.; Cooper, D.R.; McBrien, M.; Milford, R.L.; Patel, A.C. Sustainable Materials: With Both Eyes Open; UIT Cambridge Limited: Cambridge, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Evans, S.; Gregory, M.; Ryan, C.; Bergendahl, M.N.; Tan, A. Towards a Sustainable Industrial System: With Recommendations for Education, Research, Industry and Policy; Institute for Manufacturing, University of Cambridge: Cambridge, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Preston, F. A Global Redesign? Shaping the Circular Economy; Chatham House: London, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Allwood, J.M.; Ashby, M.F.; Gutowski, T.G.; Worrell, E. Material efficiency: A white paper. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2011, 55, 362–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Available online: https://buildingcircularity.org (accessed on 19 March 2022).

- Botsman, R.; Rogers, R. What’s Mine Is Yours. The Rise of Collaborative Consumption; Harper Business: New York, NY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Hamari, J.; Sjöklint, M.; Ukkonen, A. The sharing economy: Why people participate in collaborative consumption. J. Assoc. Inf. Sci. Technol. 2016, 67, 2047–2059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Owyang, J.; Tran, C.; Silva, C. The Collaborative Economy; Altimeter: Boston, MA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, P.-Y.; Wu, S.-Y. The impact and implications of on-demand services on market structure. Inf. Syst. Res. 2013, 24, 750–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, H.; Armstrong, C.M.J. Collaborative apparel consumption in the digital sharing economy: An agenda for academic inquiry. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2017, 41, 465–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamal, S.; Chu, S.-C.; Pedram, M. Materialism, attitudes, and social media usage and their impact on purchase intention of luxury fashion goods among American and Arab young generations. J. Interact. Advert. 2013, 13, 27–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fitch-Roy, O.; Benson, D.; Monciardini, D. Going around in circles? Conceptual recycling, patching and policy layering in the EU circular economy package. Environ. Politics 2020, 29, 983–1003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boudon, R. Homo sociologicus: Neither a rational nor an irrational idiot. Pap. Rev. Sociol. 2006, 80, 149–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicolini, D. Practice Theory, Work, and Organization: An Introduction; OUP Oxford: Oxford, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Evans, D.M. What is consumption, where has it been going, and does it still matter? Sociol. Rev. 2019, 67, 499–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortner, S.B. Theory in Anthropology since the Sixties. Comp. Stud. Soc. Hist. 1984, 26, 126–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaeger-Erben, M.; Offenberger, U. A practice theory approach to sustainable consumption. GAIA Ecol. Perspect. Sci. Soc. 2014, 23, 166–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yates, L.; Evans, D. Dirtying Linen: Re-evaluating the sustainability of domestic laundry. Environ. Policy Gov. 2016, 26, 101–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matiaske, W.; Menges, R.; Spiess, M. Modifying the rebound: It depends! Explaining mobility behavior on the basis of the German socio-economic panel. Energy Policy 2012, 41, 29–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorrell, S.; Dimitropoulos, J.; Sommerville, M. Empirical estimates of the direct rebound effect: A review. Energy Policy 2009, 37, 1356–1371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, D.M. After practice? Material semiotic approaches to consumption and economy. Cult. Sociol. 2020, 14, 340–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vergragt, P.J.; Cohen, M.J.; Brown, H.S. 11 Conclusion and outlook. In Social Change and the Coming of Post-Consumer Society: Theoretical Advances and Policy Implications; Routledge: Oxfordshire, UK, 2017; p. 215. [Google Scholar]

- Soper, K. Re-thinking the Good Life: The citizenship dimension of consumer disaffection with consumerism. J. Consum. Cult. 2007, 7, 205–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldberg, M.E. Social marketing: Are we fiddling while Rome burns? J. Consum. Psychol. 1995, 4, 347–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gollnhofer, J.F.; Schouten, J.W. Complementing the dominant social paradigm with sustainability. J. Marcromark. 2017, 37, 143–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, T. Prosperity without Growth? The Transition to a Sustainable Economy; Sustainable Development Commission: London, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Boyle, D. What Is New Economics? New Economics Foundation: London, UK, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Kallis, G.; Kostakis, V.; Lange, S.; Muraca, B.; Paulson, S.; Schmelzer, M. Research on degrowth. Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour. 2018, 43, 291–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soper, K. Towards a sustainable flourishing: Ethical consumption and the politics of prosperity. In Ethics and Morality in Consumption; Routledge: Oxfordshire, UK, 2016; pp. 43–59. [Google Scholar]

- Kallis, G. Limits, ecomodernism and degrowth. Political Geogr. 2021, 87, 102367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spaargaren, G.; Oosterveer, P. Citizen-consumers as agents of change in globalizing modernity: The case of sustainable consumption. Sustainability 2010, 2, 1887–1908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thongplew, N.; Spaargaren, G.; van Koppen, C.K. Companies in search of the green consumer: Sustainable consumption and production strategies of companies and intermediary organizations in Thailand. NJAS Wagening. J. Life Sci. 2017, 83, 12–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thongplew, N.; van Koppen, C.K.; Spaargaren, G. Companies contributing to the greening of consumption: Findings from the dairy and appliance industries in Thailand. J. Clean. Prod. 2014, 75, 96–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, T. Post Growth: Life after Capitalism; John Wiley Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Victor, P.; Jackson, T.; Brown, P.; Timmerman, P. Toward an Ecological Macroeconomics. In Ecological Economics for the Anthropocene: An Emerging Paradigm; Columbia University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2015; p. 237. [Google Scholar]

- Migdal, L.; MacDonald, D.A. Clarifying the relation between spirituality and well-being. J. Nerv. Ment. Dis. 2013, 201, 274–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziegler, J.; Jardine, S.; Jones, S.; van Poorten, B.; Janssen, M.; Solomon, C. Investing in the commons: Transient welfare creates incentives despite open access. Ecol. Soc. 2021, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilan, Y.V.; Pimonenko, T.V.; Starchenko, L.V. Sustainable business models for innovation and success: Bibliometric analysis. E3S Web Conf. 2020, 159, 04037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lux, M.; Greene, R. The State and Fate of Community Banking. M-RCBG Associate Working Paper No.37; John F. Kennedy School of Government, Harvard University: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Urbinati, A.; Chiaroni, D.; Chiesa, V. Towards a new taxonomy of circular economy business models. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 168, 487–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galloway, I. Peer-to-peer lending and community development finance. Community Invest. 2009, 21, 19–23. [Google Scholar]

- Adams, C.A.; Bell, S. Local energy generation projects: Assessing equity and risks. Local Environ. 2015, 20, 1473–1488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Little, V.J.; Lee, C.K.C.; Nair, S. Macro-demarketing: The key to unlocking unsustainable production and consumption systems? J. Marcromark. 2019, 39, 166–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, P.; Ward, N.; Russell, P. Moral economies of food and geographies of responsibility. Trans. Inst. Br. Geogr. 2009, 34, 12–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez-Arcos, C.; Joubert, A.M.; Scaraboto, D.; Guesalaga, R.; Sandberg, J. “How Do I Carry All This Now?” Understanding Consumer Resistance to Sustainability Interventions. J. Mark. 2021, 85, 44–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHOQOL. Available online: https://www.who.int/toolkits/whoqol (accessed on 19 March 2022).

- Maridal, J.H. A worldwide measure of societal quality of life. Soc. Indic. Res. 2017, 134, 1–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatzisarantis, N.L.; Hagger, M.S. Mindfulness and the intention-behavior relationship within the theory of planned behavior. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 2007, 33, 663–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benton, R., Jr. Reduce, reuse, recycle… and refuse. J. Marcromark. 2015, 35, 111–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, C.M. Climate change and marketing: Stranded research or a sustainable development? J. Public Aff. 2018, 18, e1893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Modi, S.; Joshi, U.; Narayanakurup, D. To what extent is mindfulness training effective in enhancing self-esteem, self-regulation and psychological well-being of school going early adolescents? J. Indian Assoc. Child Adolesc. Ment. Health 2018, 14. [Google Scholar]

- Moschis, G.P. Research frontiers on the dark side of consumer behaviour: The case of materialism and compulsive buying. J. Mark. Manag. 2017, 33, 1384–1401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inoue, M. Fostering an ecological worldview in children: Rethinking children and nature in early childhood education from a Japanese perspective. In Research Handbook on Childhoodnature: Assemblages of Childhood and Nature Research; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2020; pp. 995–1024. [Google Scholar]

- Trott, C.D. Youth-Led Climate Change Action: Multi-Level Effects on Children, Families, and Communities. Sustainability 2021, 13, 12355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Neill, C.; Buckley, J. “Mum, did you just leave that tap running?!” The role of positive pester power in prompting sustainable consumption. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2019, 43, 253–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khamis, S.; Ang, L.; Welling, R. Self-branding, ‘micro-celebrity’ and the rise of Social Media Influencers. Celebr. Stud. 2017, 8, 191–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vargo, S.L.; Lusch, R.F. Institutions and axioms: An extension and update of service-dominant logic. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2016, 44, 5–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, I.C.; Vargo, S.L. Service-dominant logic, service ecosystems and institutions: An editorial. J. Serv. Manag. 2018, 29, 518–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camacho-Otero, J.; Boks, C.; Pettersen, I.N. Consumption in the circular economy: A literature review. Sustainability 2018, 10, 2758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Weelden, E.; Mugge, R.; Bakker, C. Paving the way towards circular consumption: Exploring consumer acceptance of refurbished mobile phones in the Dutch market. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 113, 743–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donthu, N.; Kumar, S.; Mukherjee, D.; Pandey, N.; Lim, W.M. How to conduct a bibliometric analysis: An overview and guidelines. J. Bus. Res. 2021, 133, 285–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Domains | Exploring |

|---|---|

| RED | Consumption choices, based on rational decisions. |

| GREEN | Value-based consumption choices. |

| BLUE | Sociology of consumption and social practice consumption structures. |

| YELLOW | Effect of governance and policies on consumption behaviors. |

| Author | Co-Citations | Domain | Individual Level (MICRO) | Social-Organisational (MESO) | System Level (MACRO) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Shaw, D. | 705 | Ethical | [149] | ||

| Jackson, T. | 685 | Policy and gov. 1 | [150] | [151] | |

| Shove, E. | 562 | Social | [130] | [152] | |

| Thøgersen, J. | 554 | Rational | [153] | [19] | [9] |

| Stern, P.C. | 454 | Rational | [104] | [4] | |

| Steg, L. | 443 | Rational | [107] | [154] | [155] |

| Prothero, A. | 442 | Ethical | [156] | [22] | |

| Verbeke, W. | 409 | Rational | [17] | [16] | |

| Carrigan, M. | 396 | Ethical | [157] | [158] | |

| Belk, R. | 344 | Ethical | [159] | [41] | [135] |

| Newholm, T. | 343 | Ethical | [160] | [161] | |

| Dietz, T. | 342 | Rational | [103] | [4] | |

| Peattie, K. | 341 | Ethical | [108] | [29] | |

| Warde, A. | 339 | Social | [162] | ||

| Roberts, J.A. | 338 | Rational | [110] | [109] | |

| Kilbourne, W. | 329 | Ethical | [163] | [148] | |

| Lenzen, M. | 313 | Policy and gov. | [140] | [142] | |

| Seyfang, G. | 298 | Social | [128] | ||

| Spaargaren, g. | 293 | Social | [164] | [21] | |

| Lorek, s. | 294 | Policy and gov. | [165] | [144] |

| Layers | ||

|---|---|---|

| Micro | Definition | Analysed behaviours |

| Micro-level sustainable consumption research aims to reduce or refine consumption practices from the demand side. |

| |

| Meso | Definition | Analysed entities |

| Meso-level entities are the social-organizational entities shaping the consumption practices. |

| |

| Macro | Definition | Analysed |

| The dominant social paradigm created by political, economic, social and cultural, technological, and environmental factors shaping consumption practices |

| |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Haider, M.; Shannon, R.; Moschis, G.P. Sustainable Consumption Research and the Role of Marketing: A Review of the Literature (1976–2021). Sustainability 2022, 14, 3999. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14073999

Haider M, Shannon R, Moschis GP. Sustainable Consumption Research and the Role of Marketing: A Review of the Literature (1976–2021). Sustainability. 2022; 14(7):3999. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14073999

Chicago/Turabian StyleHaider, Murtaza, Randall Shannon, and George P. Moschis. 2022. "Sustainable Consumption Research and the Role of Marketing: A Review of the Literature (1976–2021)" Sustainability 14, no. 7: 3999. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14073999

APA StyleHaider, M., Shannon, R., & Moschis, G. P. (2022). Sustainable Consumption Research and the Role of Marketing: A Review of the Literature (1976–2021). Sustainability, 14(7), 3999. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14073999