Abstract

Recently, user-generated content (UGC) has been in the limelight. This study investigates why Internet users share their own UGC and reveals how the motives behind UGC sharing affect UGC sharing intentions both quantitatively and qualitatively. Based on motivations established in existing online communication literature, theoretical UGC motives are identified. Using online surveys administered to 300 users in South Korea, factor analysis is performed to identify empirical UGC sharing motives, and regression analyses shows how UGC sharing motives affect UGC sharing intention in terms of quality and quantity. A total of 10 theoretical UGC motives are consequently factorized into five motives. It is revealed that three motives—self-creation, self-expression, and reward—are related to individual purposes. Users get enjoyment from creating content, they want to be recognized by others, and further expect to be rewarded socially and economically. The other two motives, community commitment and social relationships, are related to social purposes. Users share UGC as a means of communication, desire feedback from others, and want to feel a sense of belonging within certain communities. All of these motives positively affect UGC sharing intention. This is the first study to empirically clarify UGC sharing motives. In addition, this study reveals UGC-centric self-creation and self-expression motives, which have not been the focus of previous online communication studies. Finally, the research results suggest how UGC site managers can adopt practical strategies related to UGC management.

1. Introduction

The past decade has witnessed a new communication culture that saw the content-passive-consumer transform into a content-active creator or distributor [1]. Original content created and shared by Internet users is called User Generated Content (UGC), and it is fundamentally changing the world of entertainment, communication, and information, particularly thanks to these content creators’ self-sustaining nature and ever-growing consumer numbers [2,3]. Half of the fastest growing top 10 websites were UGC-based [4], and the well-known US publication, Time magazine, selected “You” as its Person of the Year, stating that “You” are framing the new digital democracy and changing the world via the Web 2.0 (UGC) trend. Paul and Hogan [5] stated that 81% of consumers regard UGC from other consumers as an important information source when purchasing a product or service. This is accelerated by smartphone technology, as most smartphone users share their own content, such as texts, photos, and even videos via their devices [6]. UGC also has another value as data sources [7]. Based on the content created by the traveler, overall travel analytics (i.e., analysis on the flow or destination of travel) can be performed [8,9], and it can be used as experiential marketing [10].

In these circumstances, numerous companies are putting huge effort into using UGC as a means of creating new business opportunities in various domains together with new technologies such as online community, bigdata, AI, and so on [9,11]. For example, some companies provide UGC intermediary services, and other companies use UGC to create news, advertisements, educational content, and so on. Despite differences in companies’ overall business models, organizations that use UCG should capture high-quality UGC that fits with their business objectives. In addition, these companies should create strategies motivating Internet users to create and share UGC so that they have a consistent source of such content. However, many companies are yet to launch any strategically constructed system for generating UGC. As a result, the competition for limited UGC resources among UGC service providers is becoming more intense. Companies dealing with UGC services should strive to better understand why Internet users create and share their UGC and how they choose suitable websites for sharing this content. However, to our knowledge, there is no empirical research directly investigating UGC sharing motives. Moreover, little is known about the mechanism of UGC sharing among Internet users.

This study investigates why Internet users share their own UGC and reveals how the motives behind UGC sharing affect UGC sharing intentions both quantitatively and qualitatively. Previous studies on the motives behind online communication evolved as new technologies were developed. Since then, virtual communities, knowledge sharing, and online word-of-mouth have become commonplace, and we believe that investigating online communication motives can help us to understand the motives behind UGC sharing. Therefore, this study intends to determine which motives came from older modes of online communication, and which are the result of the typical characteristics of the UGC environment. Moreover, we consider which motives have the greatest effect on UGC sharing intention in terms of UGC quality (how good UGC is shared) as well as quantity (how many UGCs are shared).

2. Theoretical Background

2.1. Motives of Online Community, Knowledge Community, Electronic Word-of-Mouth

Historically, UGC can be traced back to the bulletin boards on Internet portal sites in the 1990s [2]. As time went by, UGC evolved to encompass online communities, blogs, wikis, picture sharing, video sharing, social networking, and other user-generated websites. Therefore, we need to look into the motives of online community activity, knowledge/content sharing activity, and even electronic word-of-mouth activity, in order to identify the motives behind UGC sharing.

Since the early days of the Internet, Internet users have formed virtual online communities and shared common interests within these communities for personal and social purposes [12]. In terms of personal purposes, Hars and Ou [13] investigated two major motives, “information value” and “instrumental value”. “Information value” is the motivation to acquire and share useful information and exchange opinions/voices about a common target within a community. “Instrumental value” is the motivation to solve specific problems with the help of community members and their shared knowledge. These motives are extrinsic purposes that seek practical value from a community. On the other hand, “self-satisfaction,” whereby users seek social reward (i.e., popularity or respect) via their community member relationship, is a motive of intrinsic purpose [14]. The social motives among virtual communities stem chiefly from users’ desire to “maintain interpersonal connectivity” and gain “social enhancement.” “Maintaining interpersonal connectivity” focuses on maintaining social supports, friendships, and intimacy by forming and maintaining relationships with others [14], whereas “social enhancement” focuses on gaining acknowledgement from others in the community, thereby enhancing social standing [15]. Balasubramanian and Mahajan [16] present a useful framework unifying economic motives and social motives in online community studies. This framework consists of (1) “focus-related utility,” the value that is felt as an individual adds value to his/her community, (2) “consumption utility,” the value that is felt by consuming services created by others within the community, (3) “approval utility,” the value that is felt as other members consume a particular individual’s services, (4) “moderator-related utility,” the value that is felt when a third party contributes to, or facilitates, communications within the community, and (5) “homeostasis utility,” which reflects individuals’ desire for balance or equilibrium.

As a virtual community develops and becomes specialized, knowledge management within that community becomes the most important issue for sustainable growth and success. Chiu and Hsu [17] pointed out that the biggest challenge in fostering a virtual community is the supply of knowledge, namely the willingness of community members to share knowledge with other members. Based on social cognitive theory and social capital theory, they proposed several motivations for knowledge sharing in knowledge communities. Social interaction ties [18,19], trust, norm of reciprocity [12,20], identity, shared vision, shared language, and outcome expectations (including community-related outcome expectations and personal outcome expectations) [21] were all found to influence individuals’ knowledge sharing within virtual communities. Liao and Chou [22] examined the social capital and technical determinants of knowledge adoption intentions in virtual communities and explored differences in the impact created by posters (active community members who post or contribute knowledge/content) and by lurkers (passive community members who mainly adopt rather than contribute knowledge). Structural and cognitive social capital [23,24,25], peer influence [26], and perceived usefulness positively contribute to virtual community participants’ attitudes and intentions toward knowledge adoption. In particular, posters are more affected by social trust and shared language [22]. Kaiser and Bodendorf [27] have tried to analyze opinion formation based on consumer dialogs in online knowledge forums. They distinguished two different types of opinion leaders: discussion leaders and knowledge leaders. Discussion leaders, who have high influence on other network members, exchange many statements with other discussion members. In contrast, knowledge leaders, who have expert knowledge, answer lots of questions, and other online users often assess products’ weaknesses and strengths on the basis of these users’ opinions. These two types of opinion leaders are likely to be active community participants both in terms of social interaction and of knowledge sharing.

In contrast with the knowledge community, which is organized for long-term relationships, the temporary community enables instant and timely communication through the expression of common opinions and interests. The temporary community has become a major focus of online communications research. Web-based consumer opinion or product-review platforms visited only by users when they are considering a purchase, are examples of temporary community. Traditional offline word-of-mouth is created by the “product-involvement” motivation to express evaluations related to products, “self-involvement” motivation to express consumer satisfaction with products, and “message-involvement” motivation to express opinions related to advertisements or public relationships [28]. Sundaram et al. [29] suggested that the motivation behind consumers’ positive word-of-mouth consists of “altruism,” a desire to help other consumers without any reward; “helping the company,” a desire to provide useful information for product improvement; and “self-enhancement,” a desire to get others’ attention and recognition. On the other hand, the motivation behind consumers’ negative word-of-mouth includes “anxiety reduction,” “vengeance,” and “advice seeking.” Drawing on findings from research on virtual communities and traditional word-of-mouth literature, Hennig-Thurau et al. [30] developed a typology for the motives for consumer online articulation. They revealed that consumers’ desire for “social interaction,” desire for “economic incentives,” their “concern for other consumers,” and “the potential to enhance their own self-worth” are the primary factors leading to electronic word-of-mouth behavior. Jalilvand and Samiei [31] found that online users in a tourism community often consult and gather other tourists’ online reviews to help choose an attractive destination, and that members’ advice has a significant impact on subjective norms, perceived behavioral control, and intention to visit. Also, most online users accept electronic word-of mouth articulations created with these motives to make product-purchase decisions [32,33,34,35,36], and tourism destination choices [31].

2.2. UGC Sharing Motives

Content or knowledge sharing in online communities mainly targets the limited number of people who are involved in the communities. However, UGC sharing targets unspecified individuals, using a growing number of portal sites and network technologies. Personal motivation as well as social motivation plays a key role in UGC sharing. Since sharing content via the Internet can be anonymous, the user can directly share whatever he/she wants to present, and may reveal himself/herself more frankly without any filtering [37]. Turkle [38] also mentioned that people may have more opportunities to express themselves honestly on the Internet. The motivations for creating self-images on the Internet are (1) to take pleasure in meeting people who recognize and respect an individual, in line with his/her own self-perception [39] and (2) the desire to transfer the real-life “myself,” who people do not recognize and respect in reality, to the ideal “myself,” who people like and follow [15,40]. A study identified the differences between active and passive users and the motivations behind UGC creation. Using a causal research modeling, it revealed that social status is the main motivational driver, and stimulus avoidance, social relations, and social identity is the drivers for involvement in the community [41]. Also, satisfying recognition needs, cognitive needs, social needs, and entertainment needs, as well as civic engagement, affects UGC sharing as a form of psychological empowerment [42]. Another research shows that the influence relationship of UGC sharing motives is distinguishable “according to the three separate sets (initial, sustained and meta)” [43].

This study proposes 10 motives for UGC sharing based on the above literature review. We excluded motivations that are not related to UGC sharing, such as community-dependent motives and platform-dependent motives.

We identified the following motives based on the importance of information value, social relationship, social standing, and self-satisfaction, as discussed in virtual community literature: (1) familiarity, the motivation to create more intimacy with others through UGC sharing, (2) community communication, the motivation to communicate and interact with audiences of UGC, (3) community identity, the motivation to have self-perceived qualities recognized by a community, and (4) self-enjoyment, the motivation to engage in enjoyable activity. Motives based on outcome expectations may be divided into (5) economic reward, the motivation to get some monetary reward through UGC, and (6) social reward, the motivation to improve social status (i.e., popularity, respect, etc.) through UGC. Motives based on self-development can be classed as (7) self-enhancement, the motivation to enhance the skills needed to create UGC, and (8) self-achievement, the motivation to achieve something through individual effort. Finally, motives based on the desire for self-expression can be divided into (9) uniqueness, the motivation to express who they are and show off their uniqueness, and (10) feedback, the motivation to obtain feedback on and evaluation of their UGC.

3. UGC Sharing Motives Identification and Its Effect on UGC Sharing Intentions

3.1. Structure of UGC Sharing Motives

To examine the relationships between the UGC sharing motives introduced above, we collected online survey data provided by 300 Internet users who had experience in UGC sharing. The survey participants were recruited in the online panel in their 20s and 40s from a famous Korean research company. The questionnaire was divided into two parts. The first part of survey questions asked about the experience of creating UGC, and they were used to reveal the UGC sharing motives. The second part of survey questions were about their UGC in terms of their quantity and quality. These were used for the test of our research model. The average age of these respondents was 25.4 years, and 56% were male. To share their UGC, 45% had used portal sites, such as Naver; 30% used sites that focus on UGC services, such as YouTube, Pandora, or Africa; and 15% used their own blogs or homepages.

We developed our measures of UGC sharing motives by borrowing and revising the measures used in previous studies. Table 1 shows the measures that we used in this survey.

Table 1.

UGC motivations and measurements.

To identify UGC sharing motives, we performed factor analysis with the collected data. Five independent factors are revealed, and these factors explain 83.41% of total variance. As you can see in Table 2, the results “self-achievement” and “self-enjoyment” have been amalgamated into one factor. In addition, “community identity” and “community communication” are amalgamated into a single factor. It is revealed that one factor includes “uniqueness” and “self-enhancement,” and another factor includes “familiarity” and “feedback.” The final factor includes “economic reward” and “social reward.” Other measurements that affect UGC sharing are factorized to another five factors, which are “community activeness,” “community trust,” “ease of uploading,” “community mood,” and “UGC skill.”

Table 2.

Factorized UGC motives.

3.2. UGC Sharing Motives Identification

It has been found that the 10 theoretically driven motivations for UGC sharing derived from previous studies have a certain relationship within the UGC environment. We also empirically identified five motivations. Below, we list these five factorized motivations.

Self-Creation Motive: The first factor is formed by amalgamating the “self-achievement” and “self-enjoyment” variables. We call this factor “self-creation.” Channeling effort into the creation of UGC gives the creators a feeling of achievement. This self-achievement is deeply related to self-enjoyment, to the enjoyment of the result. According to a survey of UGC, 40% of US consumers are creating their own entertainment content, including movies, re-edited movies, music, and pictures. Although people aged 13–24 represent the majority of these creators, even mature people aged 61–75 are beginning to create their own content [44]. In addition, it is reported that users upload more than 65,000 new videos to YouTube and more than six million photos to Facebook every day, most of these created by users themselves [2]. This active creation may be interpreted as the so-called “enjoyment and gratification of creation,” since people feel gratification when they create such content, and this is connected to their enjoyment.

Community Commitment Motive: The second factor is formed by amalgamating the “community identity” and “community communication” variables. In this study, we have called this factor “community commitment.” This may be interpreted to mean that users can distinguish themselves by sharing UGC, that they can provide information and enjoyment to others by sharing UGC, and that they want to communicate with others using UCG. In addition to creating intimacy between members, UGC sharing also contributes to the formation and maintenance of online communities. Online communities form when people carry on public discussions long enough with sufficient human feeling to form webs of personal relationship [45]. In virtual communities, individuals can easily find others who share similar interests and goals, and are able to voice opinions and concerns in a supportive environment [46,47]. Moreover, by joining a group, people may get a sense of communion, such as a feeling of belonging, a feeling that members matter to one another and to the group, and a shared faith that members’ needs will be met through their commitment to be together [48]. Successful communities represent places where people connect and share their interests, support, sociability, and identity [49], and are as valuable and useful as familiar, physically located communities [50]. Through UGC sharing, users can communicate and interact with other people within communities, and they also can feel affinity and a sense of belonging to communities.

Self-expression Motive: The third factor is formed by amalgamating the “uniqueness” and “self-enhancement” variables. In this study, we call this factor “self-expression.” Users can express their own identities and in particular their individuality using UGC, and they want to demonstrate or boast about this ability [2]. As these motives were not foregrounded in existing studies, they can be interpreted as UGC-specific motives, which motivate because content creators hope to reflect themselves in their work and demonstrate their uniqueness. People have a need to present their “true” or inner self to the outside world, and to have others know them as they know themselves [14,51]. Such needs can be fulfilled through blogging, video casting, and other self-presentation activities, which allow users to demonstrate the significance of who they are and what they do, and, hopefully, to have this significance recognized by others. Self-expression can be a process by which people attempt to control the impressions others have of them [52]. Bukvova [53], focusing on the online profiles of European scientists, suggested that Internet presence should be treated as an important strategic instrument for self-presentation because it can be an effective tool for communication with peers, as well as with other stakeholders. Since the Internet offers opportunities for personalized self-presentation according to individual needs [53], online users are likely to user UGC as a communication channel to reveal themselves.

Social Relationship Motive: The fourth factor is formed by amalgamating the “familiarity” and “feedback” variables. In this study, we call this factor the “social relationship.” If the self-expression motive discussed above allows users to announce themselves to others, this factor can be interpreted as enabling users to deliver opinions to one another and to get along with others by sharing UGC. People participate through interacting with the content as well as with other users on UGC sites or communities. User-to-content interaction occurs when people rate the content, save to their favorites, share with others, post comments, etc. User-to-user interaction occurs when people interact with each other through e-mail, instant message, chat room, message boards, and other Internet venues. Such interaction can be considered an indirect or direct way for individuals to fulfill their social interaction needs [2]. Responding to content (i.e., user-to-content interaction) could also be helpful for the development of online communities. This can partly be explained by the reinforcement model, which predicts that people repeat actions that lead to positive reinforcements [54]. Finally, the social relationship motive shows that Internet users use UGC as a means of intimacy within communities.

Reward Motive: This last factor is formed by amalgamating the “social reward” and “economic reward” variables. In this study, we simply call this factor “reward.” This indicates that users share UGC to become famous or to make money, so it has been found that this motive, which is often examined in the existing online communication literature, is present in the UGC-specific situation as well.

3.3. Influence of UGC Sharing Motives on UGC Sharing Intentions

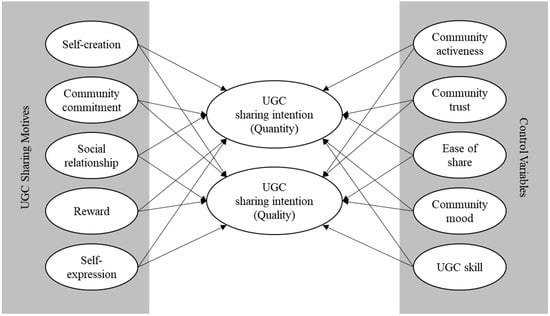

To investigate the influence of UGC sharing motives on UGC sharing intention, we performed a regression analysis. We focused on two aspects of UGC sharing: quantity and quality. In terms of quantity, we defined and measured the intention to upload many pieces of UGC continuously. In terms of quality, we asked survey participants about their intention to upload high-quality UGC. Each intention was measured using four factors and averaged for dependent variables. UGC sharing motives and other variables possibly related to UGC sharing intentions are involved in the regression analysis as control variables. Therefore, the influence of UGC sharing motives on UGC sharing intentions has been investigated more thoroughly. The research model is demonstrated in the Figure 1.

Figure 1.

The research model from UGC sharing motives to UGC sharing intention.

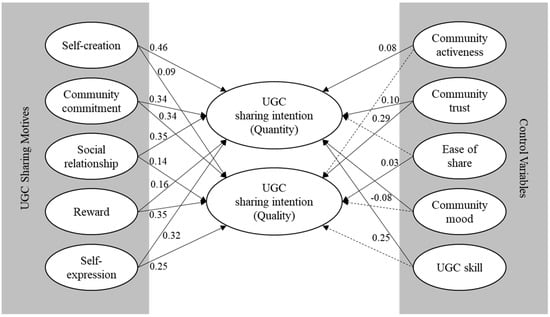

We performed a regression analysis according to our research model. The results are presented in Figure 2 and Table 3. From the perspective of quantity, it was found that all UGC sharing motives have statistically significant effects on UGC sharing. The motives are ranked by impact strength as self-creation, social relationship, community commitment, self-expression, and reward. In addition, most of the control variables are significant except ease of uploading (which was found to be only marginally significant). We can say that Internet users are motivated to increase their UGC sharing chiefly through their self-creation needs, social relation needs, community commitment needs, and self-expression needs. Relatively, the (economic or social) reward is a less effective motivator than the other motives.

Figure 2.

The results of the research model from UGC sharing motives to intention.

Table 3.

Influence of UGC motives on UGC sharing intention.

From the perspective of quality, it also was found that all UGC sharing motives have statistically significant effects on UGC sharing. However, the order by impact strength is quite different from UGC sharing intention in terms of quantity. The motives are ranked by impact strength as reward, community commitment, self-expression, social relationship, and self-creation. Two control variables, community activeness and community mood, are statistically insignificant. It is interesting to note that reward can be a powerful tool to motivate Internet users, a potentially useful finding for UGC site managers hoping to improve the quality of their site content.

4. Conclusions

Focusing on UGC, which recently has been in the limelight, this study has investigated why Internet users create UGC and what drives them to share their self-created content. We have drawn out 10 theoretical UGC motives based on existing online communication studies, and an online survey taken by 300 UGC creators was carried out. Using the data from the survey, factor analysis was performed and consequently five motives were derived empirically. Three motives among them, specifically self-creation, self-expression, and reward motives, are motives of individual purposes. These indicate that users gain enjoyment from sharing their UGC creations, that they strive to be recognized by others through their creations, and that they want to be rewarded socially and economically for their creations. The other two motives, community commitment and social relationship motives, are motives of social purpose. These indicate that users share UGC as a means of communicating within groups or communities that they belong to, to make others feel pleasure, to communicate to others using UGC, to receive feedback from others, and to heighten their sense of belonging within their group or community. This study’s findings on the influence of UGC sharing motives on UGC sharing intentions may offer some guidelines on how UGC site managers can create effective practical strategies for UGC management. As this study specifies which motive is most important for a site that requires a large quantity of UGC (e.g., a site for promoting friendship) and which motive is most important for a site requiring high-quality UGC (e.g., a site that sells UGC as a product), it may be of great interest to those online businesses that work with UGC.

This study makes several theoretical contributions. First, this study may be the first to clarify UGC sharing motives using empirical methodology. The UGC sharing motives derived here through explorative analytical methods may be of help in future research. Second, this study’s findings on the self-creation and self-expression motives may provide an opportunity to understand more deeply Internet users’ behavior regarding UGC sharing. Finally, this study reveals the influence of UGC motives on sharing intentions in terms of both quality and quantity.

The practical contributions of this study are to provide strategic guidelines for managers of online companies that feature UGC in their business models, and to enable them to make strategic decisions based on the five UGC sharing motives. The managers of these companies can secure high-quality UGC by establishing optimized UGC tools or using targeted policies, such as dividing UGC spaces into personal purpose spaces and social purpose spaces according to customers’ propensities. By creating a quantitative model based on the UGC sharing motives proposed in this study, it will be possible to manage content creators. How to motivate creators to increase the quality of UGC, and which parts motivate them to create more UGC can be systematized based on the results of this study.

This study has several limitations. First, the type of UGC targeted in this study was limited to video. Targeting UGC based on text or images could reveal other user motives. Second, this study could not identify the causal relationships between each UGC sharing motive on users’ concrete intentions. If additional study were carried out, it would be of great help to UGC decision makers. Third, a small sample size of this study was limited to generalize the research results. If this study is replicated with a larger sample size, more generally-accepted results will be revealed. Finally, the results of this study are limited to South Korea. South Korea is one of the countries that actively utilize the Internet and UGC. However, these results cannot be representative of the whole world. Since the culture of each country is thought to have an important influence, it will be very interesting to compare this study equally in several countries to derive insights for each country. Despite these limitations, this study is significant, as it has provided a starting point from which to understand Internet users’ UGC sharing intentions and their bearing on those users’ actions.

The future research of this study was presented from three perspectives. The first is the expansion dimension of the variable. This study does not take into account individual propensity or ability, and if this part such as construal level [55], psychological ownership [56,57,58], knowledge level [59] or consumer profile [60] is added, much more sophisticated insights can be derived. The second is the diversification dimension of the methodology. Using actual UGC review data or comment data such as ‘like’, if the actual amount of YouTube creators, the quality perceived by consumers, and the pattern of data are considered, a more empirical study will be possible. In addition, such actual data is formed into a relational network, so that sophisticated data analysis such as network analysis can be made possible. Finally, it is the dimension according to the evolution of the medium. A new media environment called the metaverse is emerging. When consumers enjoy content in virtual environments [61] or enjoy content with more innovative devices such as social robots [62], advances in these technologies can affect consumers’ sharing motives and outcome variables. In the future, these parts are well designed and need to be further studied.

Author Contributions

D.-H.P. analyzed the data and carried out the insights and implementation. S.-W.L. designed the model and built the logic for the hypotheses. Both shaped the research and provided essential feedback and discussion. Both authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the Ministry of Education of the Republic of Korea and the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF-2020S1A5A2A01040055).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were waived for this study, because this study did not consider biological human experiment and patient data.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy.

Acknowledgments

Do-Hyung Park thanks Yoonhee Hwang, Chaehee Park, and Chanhee Park for insightful and helpful comments.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Susarla, A.; Oh, J.-H.; Tan, Y. Social networks and the diffusion of user-generated content: Evidence from YouTube. Inf. Syst. Res. 2012, 23, 23–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, G. Understanding the appeal of user-generated media: A uses and gratification perspective. Internet Res. 2009, 19, 7–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gogan, I.; Zhang, Z.; Matemba, E. Impacts of gratifications on consumers’ emotions and continuance use intention: An empirical study of Weibo in China. Sustainability 2018, 10, 3162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Vickery, G.; Wunsch-Vincent, S. Participative Web and User-Created Content: Web 2.0 Wikis and Social Networking; Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD): Paris, France, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Paul, A.K.; Hogan, S.K. On the Couch: Understanding Consumer Shopping Behavior; Deloitte University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- US Smartphone Use in 2015. Available online: https://apo.org.au/node/59004 (accessed on 26 August 2021).

- Marine-Roig, E.; Clavé, S.A. Tourism analytics with massive user-generated content: A case study of Barcelona. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2015, 4, 162–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marine-Roig, E. Destination image analytics through traveller-generated content. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Marine-Roig, E. Measuring destination image through travel reviews in search engines. Sustainability 2017, 9, 1425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lin, M.-P.; Marine-Roig, E.; Llonch-Molina, N. Gastronomic experience (co) creation: Evidence from Taiwan and Catalonia. Tour. Recreat. Res. 2021, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Wang, J.; Fang, S.; Jin, P. Towards Sustainable Development of Online Communities in the Big Data Era: A Study of the Causes and Possible Consequence of Voting on User Reviews. Sustainability 2018, 10, 3156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dholakia, U.M.; Bagozzi, R.P. Motivational antecedents, constituents, and consequents of virtual community identity. In Virtual and Collaborative Teams; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2004; pp. 253–268. [Google Scholar]

- Alexander Hars, S.O. Working for free? Motivations for participating in open-source projects. Int. J. Electron. Commer. 2002, 6, 25–39. [Google Scholar]

- McKenna, K.Y.; Bargh, J.A. Causes and consequences of social interaction on the Internet: A conceptual framework. Media Psychol. 1999, 1, 249–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumeister, R.F. The Self. Adv. Soc. Psychol. State Sci. 2010, 139–175. Available online: https://psycnet.apa.org/record/2010-11906-005 (accessed on 26 August 2021).

- Sridhar Balasubramanian, V.M. The economic leverage of the virtual community. Int. J. Electron. Commer. 2001, 5, 103–138. [Google Scholar]

- Chiu, C.-M.; Hsu, M.-H.; Wang, E.T. Understanding knowledge sharing in virtual communities: An integration of social capital and social cognitive theories. Decis. Support Syst. 2006, 42, 1872–1888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snowden, D. A framework for creating a sustainable programme. In Knowledge Management: A Real Business Guide; Rock, S., Ed.; Caspian Publishing: London, UK, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Hsu, M.-H.; Chiu, C.-M. Internet self-efficacy and electronic service acceptance. Decis. Support Syst. 2004, 38, 369–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ridings, C.M.; Gefen, D.; Arinze, B. Some antecedents and effects of trust in virtual communities. J. Strateg. Inf. Syst. 2002, 11, 271–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. Self-Efficacy: The Exercise of Control; Macmillan: Tokyo, Japan, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Liao, S.; Chou, E.-y. Intention to adopt knowledge through virtual communities: Posters vs. lurkers. Online Inf. Rev. 2012, 36, 442–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wasko, M.M.; Faraj, S. Why should I share? Examining social capital and knowledge contribution in electronic networks of practice. MIS Q. 2005, 29, 35–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huysman, M.; De Wit, D. Practices of managing knowledge sharing: Towards a second wave of knowledge management. Knowl. Process. Manag. 2004, 11, 81–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bock, G.-W.; Zmud, R.W.; Kim, Y.-G.; Lee, J.-N. Behavioral intention formation in knowledge sharing: Examining the roles of extrinsic motivators, social-psychological factors, and organizational climate. MIS Q. 2005, 29, 87–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Negative and Positive Peer Influence: Relations to Positive and Negative Behaviors for African American, European American, and Hispanic Adolescents. Available online: https://www.acrwebsite.org/volumes/8208/volumes/v25/N (accessed on 26 August 2021).

- Kaiser, C.; Bodendorf, F. Mining patient experiences on web 2.0-A case study in the pharmaceutical industry. In Proceedings of the 2012 Annual SRII Global Conference, San Jose, CA, USA, 24–27 July 2012; pp. 139–145. [Google Scholar]

- Dichter, E. How word-of-mouth advertising works. Harv. Bus. Rev. 1966, 44, 147–160. [Google Scholar]

- Sundaram, D.S.; Mitra, K.; Webster, C. Word-of-mouth communications: A motivational analysis. ACR N. Am. Adv. 1998, 25, 527–531. [Google Scholar]

- Hennig-Thurau, T.; Gwinner, K.P.; Walsh, G.; Gremler, D.D. Electronic word-of-mouth via consumer-opinion platforms: What motivates consumers to articulate themselves on the internet? J. Interact. Mark. 2004, 18, 38–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reza Jalilvand, M.; Samiei, N. The effect of electronic word of mouth on brand image and purchase intention: An empirical study in the automobile industry in Iran. Mark. Intell. Plan. 2012, 30, 460–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Park, D.-H.; Han, I. The different effects of online consumer reviews on consumers’ purchase intentions depending on trust in online shopping malls: An advertising perspective. Internet Res. 2011, 21, 187–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, D.-H.; Kim, S. The effects of consumer knowledge on message processing of electronic word-of-mouth via online consumer reviews. Electron. Commer. Res. Appl. 2008, 7, 399–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Park, D.-H.; Lee, J. eWOM overload and its effect on consumer behavioral intention depending on consumer involvement. Electron. Commer. Res. Appl. 2008, 7, 386–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, D.-H.; Lee, J.; Han, I. The effect of on-line consumer reviews on consumer purchasing intention: The moderating role of involvement. Int. J. Electron. Commer. 2007, 11, 125–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.B.; Park, D.H. The effect of low-versus high-variance in product reviews on product evaluation. Psychol. Mark. 2013, 30, 543–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klein, J.G.; Smith, N.C.; John, A. Why we boycott: Consumer motivations for boycott participation. J. Mark. 2004, 68, 92–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Life on the Screen: Identity in the Age of the Internet. Available online: https://www.proquest.com/openview/77183c3400bf0e0e280f0011e578807c/1?pq-origsite=gscholar&cbl=48297 (accessed on 26 August 2021).

- To Be Adored or to Be Known? The Interplay of Self-Enhancement and Self-Verification. Available online: https://psycnet.apa.org/record/1990-98254-012 (accessed on 26 August 2021).

- Gollwitzer, P.M. Striving for specific identities: The social reality of self-symbolizing. In Public Self and Private Self; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1986; pp. 143–159. [Google Scholar]

- Schaedel, U.; Clement, M. Managing the online crowd: Motivations for engagement in user-generated content. J. Media Bus. Stud. 2010, 7, 17–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leung, L. User-generated content on the internet: An examination of gratifications, civic engagement and psychological empowerment. New Media Soc. 2009, 11, 1327–1347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crowston, K.; Fagnot, I. Stages of motivation for contributing user-generated content: A theory and empirical test. Int. J. Hum. -Comput. Stud. 2018, 109, 89–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- August, K.; Kern, T.; Moran, E. The State of Media Democracy: Are You Ready for the Future of Media. Diakses Melalui. Available online: www.deloitte.com/dtt/cda/doc/content/us_media_Media (accessed on 7 May 2018).

- Rheingold, H. The Virtual Community: Homesteading on the Electronic Frontier; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Group Dynamics in an E-Mail Forum. Available online: https://books.google.co.kr/books?hl=ko&lr=&id=m8PzbUOIFswC&oi=fnd&pg=PA225&dq=Group+dynamics+in+an+e-mail+forum&ots=vERJi7E1CS&sig=xuUeeT9HBSvcM1sFAWLzuPddlXs&redir_esc=y#v=onepage&q=Group%20dynamics%20in%20an%20e-mail%20forum&f=false (accessed on 26 August 2021).

- Lindlof, T.R.; Shatzer, M.J. Media ethnography in virtual space: Strategies, limits, and possibilities. J. Broadcasting Electron. Media 1998, 42, 170–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMillan, D.W.; Chavis, D.M. Sense of community: A definition and theory. J. Community Psychol. 1986, 14, 6–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wellman, B. Community: From neighborhood to network. Commun. ACM 2005, 48, 53–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cyberville: Clicks. Available online: https://www.amazon.com/Cyberville-Clicks-Culture-Creation-Online/dp/044651909X (accessed on 26 August 2021).

- Naegele, K.D.; Goffman, E. The Presentation of Self in Everyday Life. Am. Sociol. Rev. 1956, 21, 631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dominick, J.R. Who do you think you are? Personal home pages and self-presentation on the World Wide Web. Journal. Mass Commun. Q. 1999, 76, 646–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bukvova, H. A holistic approach to the analysis of online profiles. Internet Res. 2012, 22, 340–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joyce, E.; Kraut, R.E. Predicting continued participation in newsgroups. J. Comput. -Mediat. Commun. 2006, 11, 723–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lee, J.; Park, D.-H. Are you a Machine or Human?: The Effects of Human-likeness on Consumer Anthropomorphism Depending on Construal Level. J. Intell. Inf. Syst. 2021, 27, 129–149. [Google Scholar]

- Seo, B.-G.; Park, D.-H. Effective Strategies for Contents Recommendation Based on Psychological Ownership of over the Top Services in Cyberspace. J. Theor. Appl. Electron. Commer. Res. 2021, 16, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seo, B.-G.; Park, D.-H. The Effective Type of Information Categorization in Online Curation Service Depending on Psychological Ownership. Sustainability 2020, 12, 3321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Seo, B.-G.; Park, D.-H. Did You Invest Less Than Me? The Effect of Other’s Share of Investment on Psychological Ownership of Crowdfunding Projects. Sustainability 2020, 12, 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Park, D.-H. Consumer Adoption of Consumer-Created vs. Expert-Created Information: Moderating Role of Prior Product Attitude. Sustainability 2021, 13, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.-Y.; Park, D.-H. UX Methodology Study by Data Analysis Focusing on deriving persona through customer segment classification. J. Intell. Inf. Syst. 2021, 27, 151–176. [Google Scholar]

- Park, D.-H. Virtuality changes consumer preference: The effect of transaction virtuality as psychological distance on consumer purchase behavior. Sustainability 2019, 11, 6618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ha, S.; Lee, J.; Yoo, I.-J.; Park, D.-H. Different Look, Different Feel: Social Robot Design Evaluation Model Based on ABOT Attributes and Consumer Emotions. J. Intell. Inf. Syst. 2021, 27, 55–78. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).