Constructing a Socially Sustainable Culture of Participation for Caring and Inclusive ECEC

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participatory Action Research

2.2. Data

It’s wonderful to be in a workplace where no one looks bad when I am playing with children.

Veera comes to me and hopes there could be a certain day of research so that the research is not forgotten because of other things. I agree that it is a good idea. I think out loud what day would be a good one. I say that I’m not at the ECEC centre on Fridays. Veera grabs the sentence and says, ‘Then it would be good. If you are not here, we can investigate what is happening here’.(Elina’s research diary, September 2016)

2.3. Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

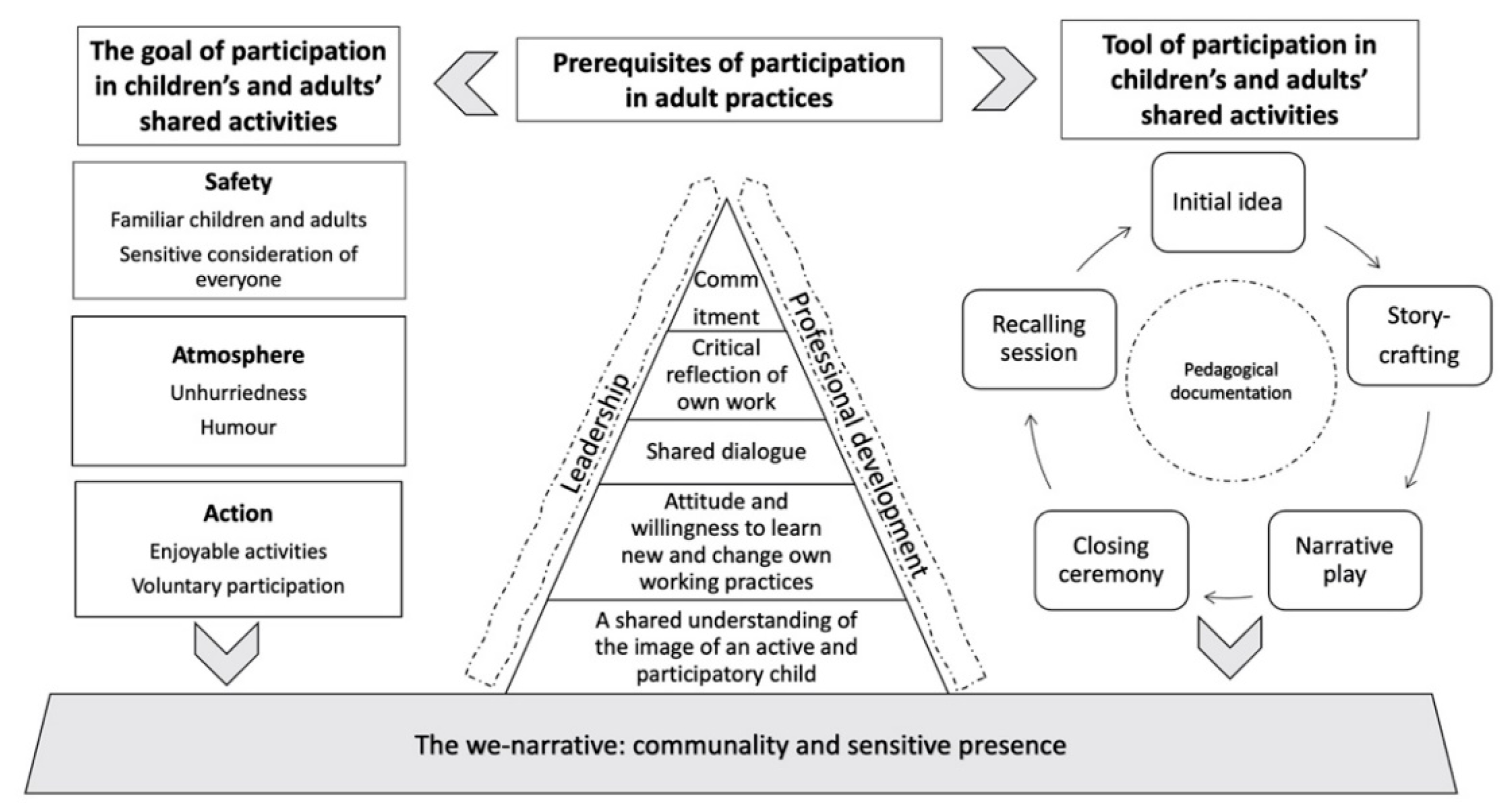

3.1. The We-Narrative as the Foundation of a Socially Sustainable Culture of Participation

Hanna (ECEC practitioner): Well because it starts with so many little things: throwing yourself into the moment, doing things together, looking for opportunities.

Anu (ECEC practitioner): Like those kinds of small things. But the very thing that WE are here, and WE do, WE go, and WE survive and so on.

3.2. The Prerequisites of Participation in Adults’ Practices

Jonna: We also have children who were able to handle it (getting dressed) but who didn’t like to be hurried. But we should give them the time they need. For some children, being together on a one-on-one basis (with an adult) so that you share this time and focus on getting them dressed to go outside gives them self-confidence. Also, it is this individual time when you get the chance to guide the child in getting dressed without hurrying.

3.3. The Goal of Participation in Children’s and Adults’ Shared Activities

Elina (researcher): In your opinion, who does the planning here in the Terhokerho Club?

Rilla: I don’t know. Maybe all the adults when they come to the meeting before the Terhokerho Club.

Rilla: Maybe in that meeting, if children would join, they could say all kinds of favourite things and funny things and nice things and stuff that adults might not agree with; maybe then the adults could carry out the children’s wishes.

3.4. The Tool of Participation in Children’s and Adults’ Shared Activities

The Ship Pansy project started with storycrafting. Anu (educator) said to the children, ‘Once upon a time there was a ship...’. The children immediately seized the idea and came up with the main characters on board. They also explained what the characters looked like, how the ship looks, what’s to be eaten, what kind of sport exercises and games are played and where the characters sleep, what they do on the ship, etc. Anu just wrote everything down exactly with the phrases the children used. One of the children came up with the name for the ship.

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- United Nations. Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development A/RES/70/1. 2015. Available online: https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/content/documents/21252030%20Agenda%20for%20Sustainable%20Development%20web.pdf (accessed on 25 January 2022).

- Imperatives, S. Report of the World Commission on Environment and Development: Our Common Future; United Nations: San Francisco, CA, USA, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Boldermo, S.; Ødegaard, E.E. What about the migrant children? The state-of-the-art in research claiming social sustainability. Sustainability 2019, 11, 459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Salonen, A.O. Sustainable Development and Its Promotion in a Welfare Society in a Global Age; University of Helsinki: Helsinki, Finland, 2010; Available online: http://urn.fi/URN:ISBN:978-952-10-6535-4 (accessed on 14 October 2021).

- Seligman, M. PERMA and the building blocks of well-being. J. Posit. Psychol. 2018, 13, 333–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alila, A.; Gröhn, K.; Kesola, I.; Volk, R. The Concept of Social Sustainability and Its Modelling; The Ministry of Social Affairs and Health: Finnish, Finland, 2011; Available online: http://urn.fi/URN:ISBN:978-952-00-3154-1 (accessed on 14 October 2021).

- Padovan, D. Social capital, lifestyles and consumption patterns. In System Innovation for Sustainability 1: Perspectives on Radical Changes to Sustainable Consumption and Production; Tukker, A., Charter, M., Vezzoli, C., Sto, E., Anderson, M.M., Eds.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2017; pp. 271–287. [Google Scholar]

- Wals, A.E. Sustainability by default: Co-creating care and relationality through early childhood education. Int. J. Early Child. 2017, 49, 155–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Somerville, M.; Williams, C. Sustainability education in early childhood: An updated review of research in the field. Contemp. Issues Early Child. 2015, 16, 102–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations. United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child; United Nations: San Francisco, CA, USA, 1989; Available online: https://www.unicef.org/crc/ (accessed on 25 January 2022).

- Siraj-Blatchford, J.; Smith, K.C.; Samuelsson, I.P. Education for Sustainable Development in the Early Years; OMEP, World Organization for Early Childhood Education: Buenos Aires, Argentina, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Ärlemalm-Hagsér, E.; Hedefalk, M. Tema: Förskolan och utbildning för hållbar utveckling, Nordisk forskning inom fältet förskolan och hållbarhet. In Utbildning & Demokrati: Tidskrift för Didaktik Och Utbildningspolitik; Langmann, E., Ljunggren, C., Eds.; Örebro Universitet: Örebro, Sweden, 2018; pp. 7–14. [Google Scholar]

- Repo, L.; Paananen, M.; Eskelinen, M.; Mattila, V.; Lerkkanen, M.-K.; Gammelgård, L.; Ulvinen, J.; Marjanen, J.; Kivistö, A.; Hjelt, H. Every-Day Quality in Early Childhood Education and Care—ECEC Curriculum Implementation at Day-Care Centres and in Family Day-Care; Finnish Education Evaluation Centre: Helsinki, Finland, 2019; Available online: https://karvi.fi/app/uploads/2019/09/KARVI_1519.pdf (accessed on 14 October 2021).

- Kirsh, E.; Frydenberg, E.; Deans, J. Benefits of an intergenerational program in the early years. J. Early Child. Educ. Res. 2021, 10, 140–164. Available online: https://jecer.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/Kirsh-Frydenberg-Deans-Issue10-2.pdf (accessed on 1 October 2021).

- Oropilla, C.T.; Ødegaard, E.E. Strengthening the Call for Intentional Intergenerational Programmes towards Sustainable Futures for Children and Families. Sustainability 2021, 13, 5564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergan, V.; Krempig, I.W.; Utsi, T.A.; Bøe, K.W. I Want to Participate—Communities of Practice in Foraging and Gardening Projects as a Contribution to Social and Cultural Sustainability in Early Childhood Education. Sustainability 2021, 13, 4368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finnish National Agency for Education. National Core Curriculum for Early Childhood Education and Care; Regulations and Guidelines 2018:3c. 2018. Available online: https://www.oph.fi/en/statistics-and-publications/publications/national-core-curriculum-early-childhood-education-and (accessed on 25 January 2022).

- Johansson, E.; Rosell, Y. Social Sustainability through Children’s Expressions of Belonging in Peer Communities. Sustainability 2021, 13, 3839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freire, P. Pedagogy of the Oppressed, 50th ed.; Bloomsbury: New York, NY, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Isaacs, W.N. Toward an action theory of dialogue. Int. J. Public Adm. 2001, 247–248, 709–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Act on Early Childhood Education and Care 540/2018. Available online: https://www.finlex.fi/fi/laki/ajantasa/2018/20180540 (accessed on 1 October 2021).

- Kangas, J.; Ojala, M.; Venninen, T. Children’s Self-Regulation in the Context of Participatory Pedagogy. Early Child. Educ. Early Educ. Dev. 2015, 265–266, 847–870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandseter, E.; Seland, M. Children’s experience of activities and participation and their subjective well-being in Norwegian ECEC institutions. Child Indic. Res. 2016, 9, 913–932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sairanen, H. Towards Relational Agency in Finnish Early Years Pedagogy and Practice; University of Helsinki: Helsinki, Finland, 2020; Available online: http://urn.fi/URN:ISBN:978-951-51-6657-9 (accessed on 14 October 2021).

- Turja, L. Children in participatory pedagogy—towards the new early childhood education. In The Early Childhood Education Today; Suomen Varhaiskasvatus ry: Tampere, Finland, 2011; Available online: https://eceaf.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/03/2011-3-Turja.pdf (accessed on 25 January 2022).

- Venninen, T.; Leinonen, J. Developing children’s participation through research and reflective practices. Asia-Pac. J. Res. Early Child. Educ. 2013, 7, 31–49. [Google Scholar]

- Finnish National Agency for Education. National Core Curriculum for Pre-Primary Education. 2014. Available online: https://verkkokauppa.oph.fi/EN/page/product/national-core-curriculum-for-pre-primary-education-2014/2453040 (accessed on 1 October 2021).

- Os, E.; Hernes, L. Children under the age of three in Norwegian childcare: Searching for qualities. In Nordic Families, Children and Early Childhood Education; Garvis, S., Harju-Luukkainen, H., Sheridan., S., Williams, P., Eds.; Palgrave Macmillan: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 139–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheridan, S.; Pramling Samuelsson, I. Children’s conceptions of participation and influence in pre-school: A perspective on pedagogical quality. Contemp. Issues Early Child. 2001, 2, 169–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vlasov, J.; Salminen, J.; Repo, L.; Karila, K.; Kinnunen, S.; Mattila, V.; Nukarinen, T.; Parrila, S.; Sulonen, H. Guidelines and Recommendations for Evaluating the Quality of Early Childhood Education and Care; Finnish Education Evaluation Centre: Helsinki, Finland, 2019; Available online: https://karvi.fi/app/uploads/2019/03/FINEEC_Guidelines-and-recommendations_web.pdf (accessed on 1 October 2021).

- Kangas, J. Enhancing Children’s Participation in Early Childhood Education through the Participatory Pedagogy; University of Helsinki: Helsinki, Finland, 2016; Available online: http://urn.fi/URN:ISBN:978-951-51-1833-2 (accessed on 14 October 2021).

- Roos, P. Children’s Storytelling about Kindergarten’s Everyday Life; Tampere University: Tampere, Finland, 2015; Available online: http://urn.fi/URN:ISBN:978-951-44-9691-2 (accessed on 14 October 2021).

- Virkki, P. Early Childhood Education Promoting Agency and Participation; University of Eastern Finland: Joensuu, Finland, 2015; Available online: https://erepo.uef.fi/bitstream/handle/123456789/14935/urn_isbn_978-952-61-1735-5.pdf (accessed on 14 October 2021).

- Kirby, P. Children’s agency in the modern primary classroom. Child. Soc. 2020, 34, 17–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sargeant, J. Towards Voice-Inclusive Practice: Finding the Sustainability of Participation in Realising the Child’s Rights in Education. Child. Soc. 2018, 32, 314–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webb, R. Negotiating the ‘3Rs’: Deconstructing the politics of ‘Rights, Respect and Responsibility’ in one English Primary School. In Education as Social Construction: Contributions to Theory, Research and Practice; Dragonas, T., Gergen, K., McNamee, S., Tseliou, E., Eds.; Taos Institute Publication: Columbus, OH, USA, 2015; pp. 283–296. [Google Scholar]

- Thomas, N. Children, Family and the State—Decision-Making and Child Participation; The Policy Press: Bristol, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Sairanen, H.; Kumpulainen, K.; Kajamaa, A. An investigation into children’s agency: Children’s initiatives and practitioners’ responses in Finnish early childhood education. Early Child Dev. Care 2020, 192, 112–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kangas, J.; Lastikka, A.-L. Children’s initiatives in the Finnish early childhood education context. In Nordic Families, Children and Early Childhood Education; Garvis., S., Harju-Luukkainen, H., Sheridan, S., Williams, P., Eds.; Palgrave Macmillan: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 15–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Venninen, T.; Leinonen, J.; Lipponen, L.; Ojala, M. Supporting children’s participation in Finnish childcare centers. Early Child. Educ. J. 2014, 42, 211–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alanen, L. Generational order. In The Palgrave Handbook of Childhood Studies; Qvortrup, J., Corsaro, W.A., Honig, M.S., Valentine, G., Eds.; Palgrave Macmillan: Cham, Switzerland, 2009; pp. 159–174. [Google Scholar]

- Karila, K. Childhood studies and activities of early childhood education and care centres. In Childhood, Childhood Institutions and Activities of Children; Alanen, L., Karila, K., Eds.; Vastapaino: Tampere, Finland, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Lipponen, L.; Kumpulainen, K.; Paananen, M. Children’s perspective to curriculum work: Meaningful moments in Finnish early childhood education. In International Handbook of Early Childhood Education; Fleer, M., van Oers, B., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2018; pp. 1265–1277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- McIntyre, A. Participatory Action Research; Sage: London, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Coghlan, D.; Brannick, T. Doing Action Research in Your Own Organization, 3rd ed.; Sage: London, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- O’Toole, L. Participant action research PAR for early childhood and primary education: The example of the THRIECE project. Probl. Wczesnej Edukac. 2020, 49, 31–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- TENK. Responsible Conduct of Research and Procedures for Handling Allegations of Misconduct in Finland. 2012. Available online: https://tenk.fi/sites/tenk.fi/files/HTK_ohje_2012.pdf (accessed on 1 January 2022).

- TENK. The Ethical Principles of Research with Human Participants and Ethical Review in the Human Sciences in Finland: Finnish National Board on Research Integrity TENK Guidelines. 2019. Available online: https://tenk.fi/sites/default/files/2021-01/Ethical_review_in_human_sciences_2020.pdf (accessed on 1 January 2022).

- Weckström, E.; Lastikka, A.-L.; Karlsson, L.; Pöllänen, S. Enhancing a Culture of Participation in Early Childhood Education and Care through Narrative Activities and Project-based Practices. J. Early Child. Educ. Res. 2021, 10, 6–32. Available online: https://jecer.org/fi/enhancing-a-culture-of-participation-in-early-childhood-education-and-care-through-narrative-activities-and-project-based-practices/ (accessed on 1 January 2022).

- Weckström, E.; Jääskeläinen, V.; Ruokonen, I.; Karlsson, L.; Ruismäki, H. Steps together: Children’s experiences of participation in club activities with the elderly. J. Intergenerational Relatsh. 2017, 15, 273–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weckström, E.; Karlsson, L.; Pöllänen, S.; Lastikka, A.-L. Creating a Culture of Participation: Early Childhood Education and Care Educators in the Face of Change. Child. Soc. 2021, 35, 503–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weckström, E. Constructing a Socially Sustainable Culture of Participation in Early Childhood Education and Care; University of Eastern Finland: 2021. Available online: http://urn.fi/URN:ISBN:978-952-61-4288-3 (accessed on 15 October 2021).

- Patton, M.Q. Qualitative Evaluation and Research Methods, 2nd ed.; Sage: London, UK, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Karlsson, L. Storycrafting method—To share, participate, tell and listen in practice and research. Eur. J. Soc. Behav. Sci. 2013, 6, 1109–1117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bush, P.L.; Pluye, P.; Loignon, C.; Granikov, V.; Wright, M.T.; Pelletier, J.F.; Repchinsky, C. Organizational participatory research: A systematic mixed studies review exposing its extra benefits and the key factors associated with them. Implement. Sci. 2017, 12, 119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patton, M.Q. Qualitative Research and Evaluation Methods, 4th ed.; Sage: London, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Lastikka, A.-L.; Kangas, J. Ethical reflections of interviewing young children: Opportunities and challenges for promoting children’s inclusion and participation. Asia-Pac. J. Res. Early Child. Educ. 2017, 11, 85–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Earl Rinehart, K. Abductive Analysis in Qualitative Inquiry. Qual. Inq. 2020, 27, 303–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kovács, G.; Spens, K.M. Abductive reasoning in logistics research. Int. J. Phys. Distrib. Logist. Manag. 2005, 35, 132–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hart, R.A. Children’s Participation: The Theory and Practice of Involving Young Citizens in Community Development and Environmental Care; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Shier, H. Pathways to participation: Openings, opportunities and obligations. Child. Soc. 2001, 15, 107–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tollefsen, D.; Gallagher, S. We-narratives and the stability and depth of shared agency. Philos. Soc. Sci. 2017, 47, 95–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grindheim, L.T.; Bakken, Y.; Hauge, K.H.; Heggen, M.P. Early Childhood Education for Sustainability Through Contradicting and Overlapping Dimensions. ECNU Rev. Educ. 2019, 2, 374–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ahonen, L. Early Childhood Educators’ Practices in Challenging Educational Situations; Tampere, Helsinki: Tampere University: 2015. Available online: http://urn.fi/URN:ISBN:978-951-44-9971-5 (accessed on 1 October 2021).

- Granrusten, P.T. Developing a learning organization—Creating a common culture of knowledge sharing—An action research project in an early childhood centre in Norway. In Leadership in Early Education in Times of Change; Strehmel, P., Heikka, J., Hujala, E., Rodd, J., Waniganayake, M., Eds.; Verlag Barbara Budrich: Leverkusen, Germany, 2020; pp. 138–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kokotsaki, D.; Menzies, V.; Wiggins, A. Project-based learning: A review of the literature. Improv. Sch. 2016, 19, 267–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uhl-Bien, M. Relational Leadership Theory: Exploring the Social Processes of Leadership and Organizing. In Leadership, Gender, and Organization. Issues in Business Ethics; Werhane, P., Painter-Morland, M., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2011; pp. 75–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Connors, M.C. Creating cultures of learning: A theoretical model of effective early care and education policy. Early Child. Res. Q. 2016, 36, 32–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoenmakers, L. Educational Change: A Relational Approach. In SAGE Handbook of Learning; Scott, D., Hargreaves, E., Eds.; Sage: London, UK, 2015; pp. 213–226. [Google Scholar]

- Koivula, M.; Hännikäinen, M. Building children’s sense of community in a day care centre through small groups in play. Early Years 2017, 37, 126–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kajamaa, A.; Kumpulainen, K. Agency in the making: Analyzing students’ transformative agency in a school-based makerspace. Mind Cult. Act. 2019, 26, 266–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Paananen, M.; Lipponen, L. Pedagogical documentation as a lens for examining equality in early childhood education. Early Child Dev. Care 2018, 188, 77–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rintakorpi, K.; Reunamo, J. Pedagogical documentation and its relation to everyday activities in early years. Early Child Dev. Care 2017, 187, 1611–1622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gubrium, J.F.; Holstein, J.A. Analyzing Narrative Reality; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Puroila, A.-M.; Estola, E.; Syrjälä, L. Does Santa exist? Children’s everyday narratives as dynamic meeting places in a day care centre context. Early Child Dev. Care 2012, 182, 191–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hännikäinen, M. The teacher’s lap—A site of emotional well-being for the younger children in day-care groups. Early Child Dev. Care 2015, 185, 752–765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Karjalainen, S.; Puroila, A.-M. The code of joy—Children’s joyful moments built dialogically and culturally in the everyday life of early childhood education and care. Kasv. Aika 2017, 11, 23–36. Available online: https://journal.fi/kasvatusjaaika/article/view/68721 (accessed on 15 January 2022).

- Stenius, T.; Karlsson, L.; Sivenius, A. Construction of Young Children’s Humour in Early Childhood and Education Centre ECEC Settings. Scand. J. Educ. Res. 2021, 66, 396–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karlsson, L. Studies of Child Perspectives in Methodology and Practice with “Osallisuus” as a Finnish Approach to Children’s Reciprocal Cultural Participation. In Childhood Cultures in Transformation: 30 Years of the UN Convention of the Rights of the Child in Action; Eriksen Ødegaard, E., Spord Borgen, J., Eds.; Brill/Sense: Leiden, The Netherlands, 2020; pp. 246–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lastikka, A.-L.; Karlsson, L. My Story, Your Story, Our Story: Reciprocal Listening and Participation through Storycrafting in Early Childhood Education and Care. In Finnish Early Childhood Education and Care—A Multi-Theoretical Perspective on Research and Practice; Harju-Luukkainen, H., Kangas, J., Garvis, S., Eds.; Springer Nature: New York, NY, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Mockler, N.; Groundwater-Smith, S. Engaging with Student Voice in Research, Education and Community: Beyond Legitimation and Guardianship; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Bae, B. Children’s Right to Participate–Challenges in Everyday Interaction. Eur. Early Child. Educ. Res. J. 2009, 17, 391–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elfström Pettersson, K. Children’s participation in preschool documentation practices. Childhood 2015, 22, 231–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knauf, H. Documentation as a tool for participation in German early childhood education and care. Eur. Early Child. Educ. Res. J. 2017, 25, 19–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jenkins, H. Confronting the Challenges of Participatory Culture: Media Education for the 21st Century; London, UK: The MIT Press: 2009. Available online: http://library.oapen.org/handle/20.500.12657/26083 (accessed on 1 October 2021).

- Kirby, P.; Lanyon, C.; Cronin, K.; Sinclair, R. Building a Culture of Participation. Involving Children and Young People in Policy, Service Planning, Delivery and Evaluation; The National Children’s Bureau: London, UK, 2003; Available online: https://core.ac.uk/reader/9983740 (accessed on 1 October 2021).

- Tammi, T.; Rautio, P.; Leinonen, R.M.; Hohti, R. Unearthing withlings: Children, tweezers, and worms and the emergence of joy and suffering in a kindergarten yard. In Research Handbook on Childhood Nature: Assemblages of Childhood and Nature Research; Cutter-Mackenzie-Knowles, A., Malone, K., Barratt Hacking, E., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2020; pp. 1309–1321. [Google Scholar]

- Juutinen, J.; Puroila, A.M.; Johansson, E. “There Is No Room for You!” The Politics of Belonging in Children’s Play Situations. In Values Education in Early Childhood Settings: Concepts, Approaches and Practices; Johansson, E., Emilson, A., Puroila, A.M., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2018; pp. 249–264. [Google Scholar]

- Puroila, A.-M.; Haho, A. Moral Functioning: Navigating the Messy Landscape of Values in Finnish Preschools. Scand. J. Educ. Res. 2017, 61, 540–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leinonen, J.; Venninen, T. Designing learning experiences together with children. Procedia-Soc. Behav. Sci. 2012, 45, 466–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Theobald, M.; Kultti, A. Investigating child participation in the everyday talk of a teacher and children in a preparatory year. Contemp. Issues Early Child. 2012, 13, 210–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Webb, R.; Crossouard, B. Learners, politics and education. In SAGE Handbook of Learning; Scott, D., Hargreaves, E., Eds.; Sage: London, UK, 2015; pp. 169–178. [Google Scholar]

- Hilppö, J.A.; Rajala, A.J.; Lipponen, L.T.; Pursi, A.; Abdulhamed, R.K. Studying Compassion in the Work of ECEC Educators in Finland: A Sociocultural Approach to Practical Wisdom in Early Childhood Education Settings. In Teachers and Families Perspectives in Early Childhood Education and Care: Early Childhood Education and Care in the 21st Century; Phillipson, S., Garvis, S., Eds.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2019; pp. 71–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lipponen, L. Constituting Cultures of Compassion in Early Childhood Educational Settings. In Nordic Dialogues on Children and Families; Garvis, S., Ødegaard, E.E., Eds.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Rajala, A.; Lipponen, L. Early Childhood Education and Care in Finland: Compassion in narrations of early childhood education student teachers. In International Perspectives on Early Childhood Education and Care: Early Childhood Education in the 21st Century; Garvis, S., Phillipson, S., Harju-Luukkainen, H., Eds.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2018; pp. 64–75. [Google Scholar]

- Chatzidakis, A.; Hakim, J.; Litter, J.; Rottenberg, C. The Care Manifesto: The Politics of Interdependence; Verso Books: London, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Hofstede Insights. 2022. Available online: https://www.hofstede-insights.com (accessed on 15 January 2022).

- Katainen, A.H. Us, others and Finnish individualism. In Beyond the Sociological Imagination: A Festschrift in Honour of Professor Pekka Sulkunen; Hellman, M., Katainen, A., Alanko, A., Egerer, M., Koski-Jännes, A., Eds.; University of Helsinki: Helsinki, Finland, 2016; pp. 29–34. Available online: http://blogs.helsinki.fi/hu-ceacg/files/2011/11/Link-to-pdf-version.pdf (accessed on 15 January 2022).

- Nishimura, S.; Nevgi, A.; Tella, S. Communication style and cultural features in high/low context communication cultures: A case study of Finland, Japan and India. In Renewing and Evolving Subject Didactics: Subject Didactic Symposium 8.2.2008 Helsinki; Kallioniemi, A., Ed.; University of Helsinki: Helsinki, Finland, 2008; Part 2, pp. 783–796. [Google Scholar]

- Onnismaa, E.L.; Paananen, M. The formation of ECEC curriculum tradition in Finland from the 1970’s to 2010’s. In Transitions and Signs of Time in Education: Perspectives on the Curriculum Research; Autio, T., Hakala, L., Kujala, T., Eds.; Tampere University Press: Tampere, Helsinki, 2019; pp. 189–220. [Google Scholar]

- Alderson, P.; Morrow, V. The Ethics of Research with Children and Young People: A Practical Handbook; Sage: London, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Juuti, P.; Puusa, A. (Eds.) Action research. Both action and research. In Approaches and Methods in Qualitative Research; Chapter 17; Gaudeamus: Helsinki, Finland, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Hujala, E.; Fonsen, E.; Heikka, J. Research-based development activities as a tool for leadership. In On the Border of Public and Private Services: The Change of Public Services; Anttonen, A., Haveri, A., Lehto, J., Palukka, H., Eds.; Tampere University Press: Tampere, Finland, 2012; pp. 335–357. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, Y.-J.; Recchia, S.L. Zooming In and Out: Exploring Teacher Competencies in Inclusive Early Childhood Classrooms. J. Res. Child. Educ. 2016, 30, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Agency for Special Needs and Inclusive Education. Raising the Achievement of All Leaners: A Resource to Support Self-Review. 2017. Available online: https://www.european-agency.org/sites/default/files/raising_achievement_self-review.pdf (accessed on 15 January 2022).

- Lastikka, A.-L. Culturally and Linguistically Diverse Children’s and Families’ Experiences of Participation and Inclusion in Finnish Early Childhood Education and Care; University of Helsinki: Helsinki, Finland, 2019; Available online: http://urn.fi/URN:NBN:fi-fe2019102835162 (accessed on 14 October 2021).

- Felder, F. The Value of Inclusion. J. Philos. Educ. 2018, 52, 54–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winter, R. Truth or fiction: Problems of validity and authenticity in narratives of action research. Educ. Action Res. 2002, 10, 143–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niemelä, R. Inclusionary Practices in a Finnish Pre-Primary School Context. University of Helsinki. 2015. Available online: http://urn.fi/URN:ISBN:978-951-51-0196-9 (accessed on 15 January 2022).

- Arvola, O.; Lastikka, A.; Reunamo, J. Increasing Immigrant Children’s Participation in the Finnish Early Childhood Education Context. Eur. J. Soc. Behav. Sci. 2017, 20, 294–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Justice, L.M.; Logan, J.A.R.; Lin, T.-J.; Kaderavek, J.N. Peer Effects in Early Childhood Education: Testing the Assumptions of Special-Education Inclusion. Psychol. Sci. 2014, 25, 1722–1729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Unesco. The Salamanca Statement and Framework for Action on Special Needs Education; Unesco: Paris, France, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Kangas, J.; Lastikka, A.-L.; Karlsson, L. Empowering Early Childhood Education and Care: Play, Participation and Well-Being of a Child; Otava: Helsinki, Finland, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Millei, Z. Re-orientating and Re-acting to Diversity in Finnish Early Childhood Education and care. J. Early Child. Educ. Res. 2019, 8, 47–58. Available online: https://jecer.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/08/Millei-issue8-1.pdf (accessed on 15 January 2022).

- Lansdown, G. See Me, Hear Me: A Guide to Using the UN Convention on the Rights of Persons With Disabilities to Promote the Rights of Children; Save the Children UK: London, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Woodhead, M. Changing perspectives on early childhood: Theory, research and policy. Int. J. Equity Innov. Early Child. 2006, 4, 1–43. Available online: http://oro.open.ac.uk/6778/1/Woodhead_paper_for_UNESCO_EFA_2007.pdf (accessed on 15 October 2021).

- Mentha, S.; Church, A.; Page, J. Teachers as Brokers: Perceptions of “Participation” and Agency in Early Childhood Education and Care. Int. J. Child. Rights 2015, 23, 622–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Data 1 | Data 2 | Data 3 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Article | Weckström, E., Jääskeläinen, V., Ruokonen, I., Karlsson, L., and Ruismäki, H. (2017). ‘Steps together–Children’s experiences of participation in club activities with the elderly.’ Journal of Intergenerational Relationships, 15(3), 273–289. | Weckström, E., Karlsson, L., Pöllänen, S., and Lastikka, A-L. (2021). ‘Creating a culture of participation: Early childhood education and care educators in the face of change.’ Children & Society, 35(4), 503–518. | Weckström, E., Lastikka, A-L., Karlsson, L., and Pöllänen, S. (2021). ‘Enhancing a culture of participation in early childhood education and care through narrative activities and project-based practices.’ Journal of Early Childhood Education Research, 10(1), 6–32. |

| Research question(s) | In what ways do children feel that they are part of the group? In what ways do children feel that they can take initiative in organising activities? | Which elements are critical in the development and construction of a culture of participation? | How do narrative activities and project-based practices promote the development of a culture of participation, which supports reciprocal and listening practices emerging from children’s initiatives and interests? |

| Participants | Aged 4 to 12 years (N = 12) | ECEC practitioners (N = 19) | Aged 3 to 7 years (N = 41) |

| ECEC leaders (N = 2) | ECEC practitioners (N = 3) | ||

| Data | Interviews (N = 8) | Group conversations (N = 4) | Pedagogical projects (N = 4) |

| Stimulated recall conversation (N = 1) Team conversations (N = 8) Diary notes of ECEC practitioners (N = 9) Field notes of the first leader (N = 1) | |||

| Data analysis method | Content analysis | Thematic analysis | Narrative analysis |

| Findings | Children’s experiences of participation are built on the following: Familiar children and adults Sensitive consideration of everyone Enjoyable activities Humour Unhurriedness Voluntary participation | The critical elements of the development and construction of a culture of participation are as follows: A shared understanding of the image of an active child A shared understanding of communal professional development Relational and reciprocal leadership A shared we-narrative that enables the comprehensive understanding, promotion, and maintenance of a culture of participation | The following phases show how the planning, implementation, and evaluation of the shared narrative activities of children and educators supporting a culture of participation: Initial ideas Storycrafting Narrative play Closing ceremony Recalling sessions The phases are not separate, and a project is not always straightforward |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Weckström, E.; Lastikka, A.-L.; Havu-Nuutinen, S. Constructing a Socially Sustainable Culture of Participation for Caring and Inclusive ECEC. Sustainability 2022, 14, 3945. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14073945

Weckström E, Lastikka A-L, Havu-Nuutinen S. Constructing a Socially Sustainable Culture of Participation for Caring and Inclusive ECEC. Sustainability. 2022; 14(7):3945. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14073945

Chicago/Turabian StyleWeckström, Elina, Anna-Leena Lastikka, and Sari Havu-Nuutinen. 2022. "Constructing a Socially Sustainable Culture of Participation for Caring and Inclusive ECEC" Sustainability 14, no. 7: 3945. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14073945

APA StyleWeckström, E., Lastikka, A.-L., & Havu-Nuutinen, S. (2022). Constructing a Socially Sustainable Culture of Participation for Caring and Inclusive ECEC. Sustainability, 14(7), 3945. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14073945