Corporate Social Responsibility Preferences in South Africa

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. CSR in South Africa

3. National Level

4. Industry Level

5. Method

5.1. Sample and Data Collection

5.2. Measures

5.2.1. National CSR Preferences

5.2.2. Industry

5.2.3. Control Variables

5.3. Data Analysis

6. Results

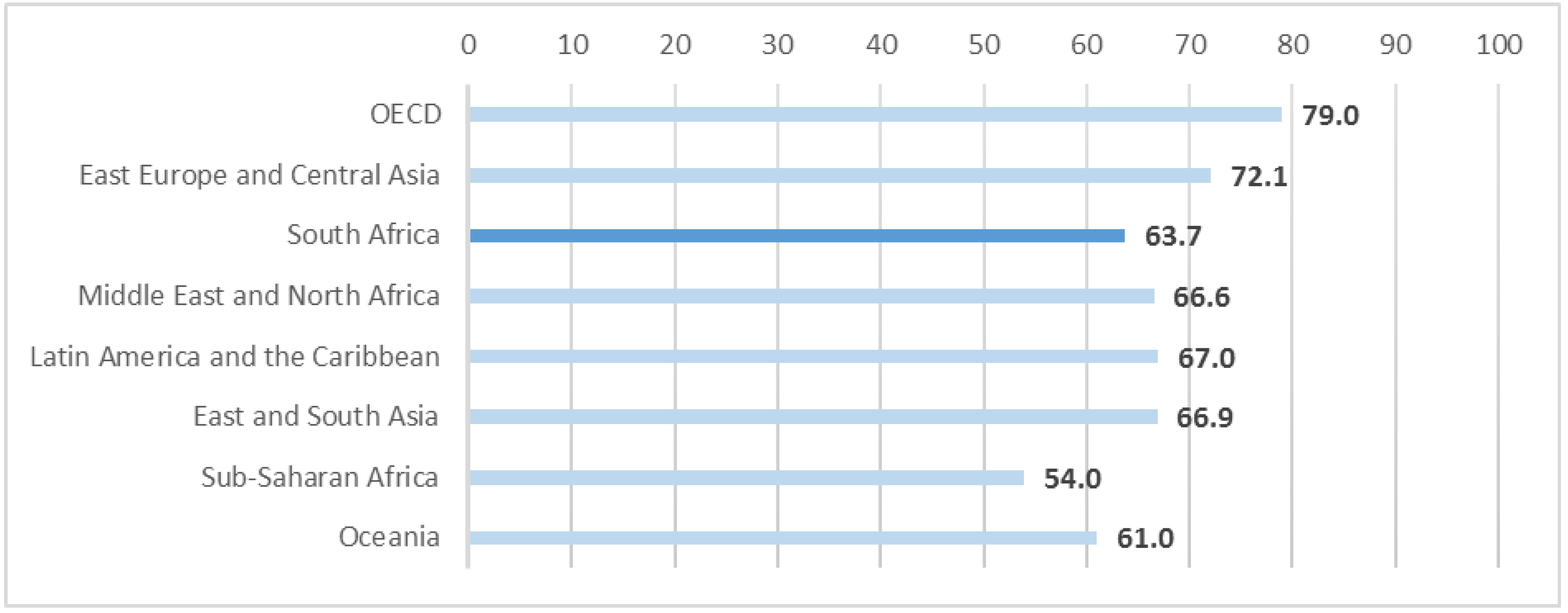

6.1. CSR Preferences in South Africa

6.2. Industry Influence

7. Discussion

7.1. National Level CSR Preferences

7.2. Industry Influence

8. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hahn, R. ISO 26000 and the Standardization of Strategic Management Processes for Sustainability and Corporate Social Responsibility. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2013, 22, 442–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brammer, S.; Jackson, G.; Matten, D. Corporate Social Responsibility and Institutional Theory: New Perspectives on Private Governance. Socio-Econ. Rev. 2012, 10, 3–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munro, V. Stakeholder Preferences for Particular Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) Activities and Social Initiatives (SIs): CSR Initiatives to Assist Corporate Strategy in Emerging and Frontier Markets. J. Corp. Citizsh. 2013, 51, 72–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciocirlan, C.; Pettersson, C. Does Workforce Diversity Matter in the Fight against Climate Change? An Analysis of Fortune 500 Companies. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2012, 19, 47–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, S.; Marais, M. A Multi-Level Perspective of CSR Reporting: The Implications of National Institutions and Industry Risk Characteristics. Corp. Gov. Int. Rev. 2012, 20, 432–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, N.; Moon, J. Institutional Complementarity between Corporate Governance and Corporate Social Responsibility: A Comparative Institutional Analysis of Three Capitalisms. Socio-Econ. Rev. 2012, 10, 85–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matten, D.; Moon, J. “Implicit” and “Explicit” CSR: A Conceptual Framework for a Comparative Understanding of Corporate Social Responsibility. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2008, 33, 404–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Connor, A.; Gronewold, K.L. Black Gold, Green Earth: An Analysis of the Petroleum Industry’s CSR Environmental Sustainability Discourse. Manag. Commun. Q. 2013, 27, 210–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, J.; Liang, M.; Zhang, C.; Rong, D.; Guan, H.; Mazeikaite, K.; Streimikis, J. Assessment of Corporate Social Responsibility by Addressing Sustainable Development Goals. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2021, 28, 686–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loose, S.M.; Remaud, H. Impact of Corporate Social Responsibility Claims on Consumer Food Choice: A Cross-Cultural Comparison. Br. Food J. 2013, 115, 142–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanco, M.; Lerro, M. Consumers’ Preferences for and Perception of CSR Initiatives in the Wine Sector. Sustainability 2020, 12, 5230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehta, R.; Bhanja, N. Consumer Preferences for Wine Attributes in an Emerging Market. Int. J. Retail Distrib. Manag. 2018, 46, 34–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lerro, M.; Vecchio, R.; Caracciolo, F.; Pascucci, S.; Cembalo, L. Consumers’ Heterogeneous Preferences for Corporate Social Responsibility in the Food Industry. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2018, 25, 1050–1061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, X.; Chen, X.; Ning, L. The Roles of Macro and Micro Institutions in Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR). Manag. Decis. 2018, 56, 955–971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Zeng, S.; Lin, H.; Ma, H. Munificence, Dynamism, and Complexity: How Industry Context Drives Corporate Sustainability. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2017, 26, 125–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowen, H. Social Responsibility of the Businessman; Harper and Row: New York, NY, USA, 1953. [Google Scholar]

- Davis, K. The Case for and Against Business Assumption of Social Responsibilities. Acad. Manag. J. 1973, 16, 312–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carroll, A.B. A Three-Dimensional Conceptual Model of Corporate Social Performance. Academy of Management Review. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1979, 4, 497–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bansal, P.; Song, H.C. Similar but Not the Same: Differentiating Corporate Sustainability from Corporate Responsibility. Acad. Manag. Ann. 2017, 11, 105–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elkington, J. Accounting for the Triple Bottom Line. Meas. Bus. Excell. 1998, 2, 18–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Parliament and the Council of the European Union Directive 2014/95/EU of the European Parliament and of the Council of 22. Available online: https://www.legislation.gov.uk/eudr/2014/95/adopted (accessed on 4 March 2022).

- European Commission. Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions: A Renewed EU Strategy 2011–14 for Corporate Social Responsibility. Brussels. 2011. Available online: https://publications.europa.eu/en/publication-detail/-/publication/ae5ada03-0dc3-48f8-9a32-0460e65ba7ed/language-en (accessed on 4 January 2021).

- Mares, R. Global Corporate Social Responsibility, Human Rights and Law: An Interactive Regulatory Perspective on the Voluntary-Mandatory Dichotomy. Transnatl. Leg. Theory 2010, 1, 221–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IMF South Africa: 2019 Article IV Consultation-Press Release; and Staff Report; and Statement by the Executive Director for South Africa. Available online: https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/CR/Issues/2020/01/29/South-Africa-2019-Article-IV-Consultation-Press-Release-and-Staff-Report-and-Statement-by-49003 (accessed on 4 March 2022).

- CIA 2014—The World Factbook. Available online: https://www.cia.gov/the-world-factbook/about/cover-gallery/2014-cover/ (accessed on 4 March 2022).

- StatsSA Quarterly Labour Force Survey (QLFS)—Q3:2021|Statistics South Africa. Available online: http://www.statssa.gov.za/?p=14957 (accessed on 4 January 2021).

- Mbeki Statement of Deputy President Thabo Mbeki at the Opening of the Debate in the National Assembly, on Reconciliation and Nation Building, National Assembly Cape Town, 29 May 1998. Available online: http://www.dirco.gov.za/docs/speeches/1998/mbek0529.htm (accessed on 4 March 2022).

- Patel, L. Social Welfare and Social Development (2nd Edition). Soc. Work 2016, 52, 301–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Rajak, D. The Gift of CSR: Power and the Pursuit of Responsibility in the Mining Industry. In Corporate Citizenship in Africa; Routledge: London, UK, 2017; pp. 190–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamann, R. Corporate Social Responsibility, Partnerships, and Institutional Change: The Case of Mining Companies in South Africa. Nat. Resour. Forum 2004, 28, 278–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arya, B.; Bassi, B. Corporate Social Responsibility and Broad-Based Black Economic Empowerment Legislation in South Africa: Codes of Good Practice. Bus. Soc. 2011, 50, 674–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shubane, K.; Reddy, C.D. BEE 2007: Empowerment and Its Critics; BusinessMap Foundation: Johannesburg, South Africa, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Shubane, K.; Reddy, C.D. BEE 2005: Behind the Deals; BusinessMap Foundation: Johannesburg, South Africa, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Reddy, C.D.; Hamann, R. Distance Makes the (Committed) Heart Grow Colder: MNEs’ Responses to the State Logic in African Variants of CSR. Bus. Soc. 2018, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de la Vega, C. The Special Measures Mandate of the International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination: Lessons from the United States and South Africa. J. Int. Comp. Law 2009, 16, 627. [Google Scholar]

- Ackers, B.; Eccles, N.S. Mandatory Corporate Social Responsibility Assurance Practices. Account. Audit. Account. J. 2015, 28, 515–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- JSE FTSE/JSE Responsible Investment Index Series|Johannesburg Stock Exchange. Available online: https://www.jse.co.za/services/indices/ftsejse-responsible-investment-index-series (accessed on 19 January 2021).

- Skinner, C.; Mersham, G. Corporate Social Responsibility in South Africa: Emerging Trends. Soc. Bus. Rev. 2008, 3, 239–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Da Piedade, L.; Thomas, A. The Case for Corporate Responsibility: Arguments from the Literature. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2006, 4, 57–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heese, K. The Development of Socially Responsible Investment in South Africa: Experience and Evolution of SRI in Global Markets. Dev. S. Afr. 2005, 22, 729–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sonnenberg, D.; Hamann, R. The JSE Socially Responsible Investment Index and the State of Sustainability Reporting in South Africa. Dev. S. Afr. 2006, 23, 305–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maubane, P.; Prinsloo, A.; van Rooyen, N. Sustainability Reporting Patterns of Companies Listed on the Johannesburg Securities Exchange. Public Relat. Rev. 2014, 40, 153–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CSR Hub CSR Ratings by Region and Country. Available online: https://www.csrhub.com/CSR_ratings_by_region_and_country/ (accessed on 2 March 2022).

- Sachs, J.; Kroll, C.; Lafortune, G.; Fuller, G.; Woelm, F. Sustainable Development Report 2021; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Visser, W. Corporate Social Responsibility in Developing Countries. In The Oxford Handbook of Corporate Social Responsibility; Crane, A., McWilliams, A., Matten, D., Moon, J., Siegel, D., Eds.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Mersham, G.M.; Skinner, C. South Africa’s Bold and Unique Experiment in CSR Practice. Soc. Bus. Rev. 2016, 11, 110–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, J.L. Why Would Corporations Behave in Socially Responsible Ways? An Institutional Theory of Corporate Social Responsibility. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2007, 32, 946–967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geerts, M.; Dooms, M.; Stas, L. Determinants of Sustainability Reporting in the Present Institutional Context: The Case of Port Managing Bodies. Sustainability 2021, 13, 3148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DiMaggio, P.J.; Powell, W.W. The Iron Cage Revisited: Institutional Isomorphism and Collective Rationality in Organizational Fields. Am. Sociol. Rev. 1983, 48, 147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, W.R. Institutions and Organizations: Ideas and Interests; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Suchman, M.C. Managing Legitimacy: Strategic and Institutional Approaches. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1995, 20, 571–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herold, D.M.; Farr-Wharton, B.; Lee, K.H.; Groschopf, W. The Interaction between Institutional and Stakeholder Pressures: Advancing a Framework for Categorising Carbon Disclosure Strategies. Bus. Strategy Dev. 2019, 2, 77–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguilera, R.V.; Rupp, D.E.; Williams, C.A.; Ganapathi, J. Putting the s Back in Corporate Social Responsibility: A Multilevel Theory of Social Change in Organizations. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2007, 32, 836–863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, S. Communication of Corporate Social Responsibility Activities by Private Sector Companies in India: Research Findings and Insights. Metamorph. J. Manag. Res. 2015, 14, 30–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, G.; Apostolakou, A. Corporate Social Responsibility in Western Europe: An Institutional Mirror or Substitute? J. Bus. Ethics 2010, 94, 371–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snider, J.; Hill, R.P.; Martin, D. Corporate Social Responsibility in the 21st Century: A View from the World’s Most Successful Firms. J. Bus. Ethics 2003, 48, 175–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buchanan, S.; Marques, J.C. How Home Country Industry Associations Influence MNE International CSR Practices: Evidence from the Canadian Mining Industry. J. World Bus. 2018, 53, 63–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kilian, T.; Hennigs, N. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Reporting in Controversial Industries. Eur. Bus. Rev. 2014, 26, 79–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tagesson, T.; Blank, V.; Broberg, P.; Collin, S.O. What Explains the Extent and Content of Social and Environmental Disclosures on Corporate Websites: A Study of Social and Environmental Reporting in Swedish Listed Corporations. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2009, 16, 352–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russo, M.V.; Fouts, P.A. A Resource-Based Perspective on Corporate Environmental Performance and Profitability. Acad. Manag. J. 1997, 40, 534–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brammer, S.; Millington, A. The Effect of Stakeholder Preferences, Organizational Structure and Industry Type on Corporate Community Involvement. J. Bus. Ethics 2003, 45, 213–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rhee, Y.P.; Park, C.; Petersen, B. The Effect of Local Stakeholder Pressures on Responsive and Strategic CSR Activities. Bus. Society 2018, 60, 582–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ojo, O. Nigeria: CSR as a Vehicle for Economic Development. In Global Practices of Corporate Social Responsibility; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2009; pp. 393–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; Seo, K.; Sharma, A. Corporate Social Responsibility and Firm Performance in the Airline Industry: The Moderating Role of Oil Prices. Tour. Manag. 2013, 38, 20–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gelles, G.M.; Mitchell, D.W. Returns to Scale and Economies of Scale: Further Observations. J. Econ. Educ. 1996, 27, 259–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, S.; Suar, D. Does Corporate Social Responsibility Influence Firm Performance of Indian Companies? J. Bus. Ethics 2010, 95, 571–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, C.Y.J.; Lee, K.L.; Ingersoll, G.M. An Introduction to Logistic Regression Analysis and Reporting. J. Educ. Res. 2002, 9, 3–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Klerk, M.; de Villiers, C. The Value Relevance of Corporate Responsibility Reporting: South African Evidence. Meditari Account. Res. 2012, 20, 21–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hur, W.M.; Kim, Y. How Does Culture Improve Consumer Engagement in CSR Initiatives? The Mediating Role of Motivational Attributions. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2017, 24, 620–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Powell, W.W.; DiMaggio, P.J. The New Institutionalism in Organizational Analysis; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Hilson, G. An Overview of Land Use Conflicts in Mining Communities. Land Use Policy 2002, 19, 65–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Govindan, K.; Kannan, D.; Shankar, K.M. Evaluating the Drivers of Corporate Social Responsibility in the Mining Industry with Multi-Criteria Approach: A Multi-Stakeholder Perspective. J. Clean. Prod. 2014, 84, 214–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olanipekun, A.O.; Oshodi, O.S.; Darko, A.; Omotayo, T. The State of Corporate Social Responsibility Practice in the Construction Sector. Smart Sustain. Built Environ. 2020, 9, 91–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jenkins, H. Corporate Social Responsibility and the Mining Industry: Conflicts and Constructs. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2004, 11, 23–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garrone, P.; Melacini, M.; Perego, A. Surplus Food Recovery and Donation in Italy: The Upstream Process. Br. Food J. 2014, 116, 1460–1477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Statistics South Africa. Towards Measuring the Extent of Food Security in South Africa; StatsSA: Pretoria, South Africa, 2019; Volume 03-00-14. [Google Scholar]

- Feng, M.; Wang, X.; Kreuze, J.G. Corporate Social Responsibility and Firm Financial Performance. Am. J. Bus. 2017, 32, 106–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glavas, A. Corporate Social Responsibility and Employee Engagement: Enabling Employees to Employ More of Their Whole Selves at Work. Front. Psychol. 2016, 7, 796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farooq, Q.; Liu, X.; Fu, P.; Hao, Y. Volunteering Sustainability: An Advancement in Corporate Social Responsibility Conceptualization. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2020, 27, 2450–2464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Element | Weighting |

|---|---|

| Black ownership | 25 |

| Management | 15 |

| Skills development | 20 |

| Enterprise and supplier development | 40 |

| Socio economic development | 5 |

| Type of Sector | Number of Firms | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Finance | 38 | 16.45 |

| Real Estate | 29 | 12.55 |

| Mining | 28 | 12.12 |

| Manufacturing | 37 | 16.02 |

| Construction | 14 | 6.06 |

| Communication | 15 | 6.49 |

| Catering and Accommodation | 10 | 4.33 |

| Wholesale and Retail Trade | 26 | 11.26 |

| Support Services | 28 | 12.12 |

| Transport and storage | 4 | 1.73 |

| Agriculture | 1 | 0.43 |

| Electricity, Gas and Water | 1 | 0.43 |

| Total | 231 | 100 |

| CSR Activity | Description | N * | Mean | Standard Deviation | Rank |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Education | Scholarships; bursaries; in-service training for educators; partner with educational institutions; early childhood development programs. | 156 | 0.671 | 0.471 | 1 |

| Training and Skills and Development | Sponsoring work readiness programs; learnership programs for the unemployed; financial literacy and money management skills; adult literacy and numeracy skills. | 130 | 0.563 | 0.497 | 2 |

| Charitable Donations | Donate food and clothing; disaster and humanitarian relief funds. | 128 | 0.550 | 0.499 | 3 |

| Enterprise Development | Incubator programs for small businesses; credit solutions; financial support and coaching small and micro enterprises; partner with existing local suppliers; procure goods and services from local community businesses. | 91 | 0.390 | 0.489 | 4 |

| Infrastructure | Building and upgrading roads, schools, health facilities; water supply to communities. | 87 | 0.372 | 0.484 | 5 |

| Health and Safety | Improve access to quality and affordable healthcare; assistance with medical equipment; raise awareness on health issues; sponsor vaccinations and medical treatments; managing occupational health risks. | 80 | 0.356 | 0.477 | 6 |

| Youth Development Program | Job creation for youths; youth sponsorship to develop life skills. | 53 | 0.239 | 0.421 | 7 |

| Employee Engagement | Employees support company outreach programs; employee volunteerism in communities. | 50 | 0.226 | 0.413 | 8 |

| Arts, Culture and Sport | Sponsor sports, cultural and art activities. | 61 | 0.213 | 0.41 | 9 |

| Food Security | Provide nutrition to vulnerable children; sustainable farming; quality seeds; strengthening the food value chain. | 27 | 0.127 | 0.322 | 10 |

| Variables | EDU | TSD | HS | YDP | EMP-E | CD | ENT-D | INFR | FS | ACS |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Constant | 15.622 ** | 1.247 | 1.041 | 0.234 | 1.255 | 0.394 | 0.150 ** | 0.548 | 0.181 | 0.348 |

| Finance | 0.629 | 1.886 | 0.818 | 0.516 | 4.709 ** | 1.367 | 2.631 | 1.114 | 0.817 | 1.156 |

| Real Estate | 0.664 | 0.707 | 0.440 | 0.452 | 0.479 | 1.093 | 1.487 | 0.685 | 1.134 | 0.251 |

| Mining | 0.388 | 0.617 | 1.836 | 1.557 | 0.111. | 0.239 ** | 4.990 ** | 3.859 * | 0.437 | 0.168 ** |

| Manufacturing | 0.348. | 1.129 | 1.485 | 0.317. | 0.824 | 0.311 * | 3.507 * | 0.956 | 1.064 | 0.716 |

| Construction | 0.198 * | 2.166 | 0.812 | 1.835 | 0.293 | 0.142 ** | 4.016. | 8.097 ** | 0.420 | 0.170 |

| Communication | 0.202 * | 0.748 | 2.140 | 1.019 | 1.201 | 1.286 | 1.541 | 0.570 | 0.000 | 0.820 |

| Catering and accommodation | 0.284 | 0.573 | 0.488 | 0.661 | 0.398 | 0.577 | 1.762 | 0.567 | 2.355 | 2.224 |

| Support services | 0.233 * | 2.593 | 1.135 | 0.850 | 0.654 | 1.122 | 2.996. | 1.715 | 0.203 | 0.168 ** |

| Transport | 0.067 * | 0.878 | 0.000 | 0.648 | 4.078 | 0.000 | 3.929 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.736 |

| Profit | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.001 | 0.996. | 1.000 | 0.998 | 1.000 | 0.998. | 1.000 | 1.000 |

| Size | 0.924 | 0.995 | 0.949 | 1.038 | 0.894 | 1.116 | 1.036 | 0.985 | 1.001 | 1.019 |

| No. of observations | 229 | 229 | 225 | 229 | 229 | 225 | 229 | 225 | 210 | 229 |

| Log pseudo- Likelihood | −137.023 | −149.796 | −138.760 | −115.577 | −100.579 | −137.932 | −146.123 | −134.318 | −76.839 | −106.477 |

| Wald chi2 | 15.140 | 12.840 | 14.460 | 13.140 | 30.890 *** | 28.870 *** | 12.190 | 25.010 ** | 6.600 | 19.650 * |

| Pseudo R2 | 0.059 | 0.044 | 0.049 | 0.067 | 0.163 | 0.112 | 0.042 | 0.097 | 0.046 | 0.094 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Cheruiyot-Koech, R.; Reddy, C.D. Corporate Social Responsibility Preferences in South Africa. Sustainability 2022, 14, 3792. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14073792

Cheruiyot-Koech R, Reddy CD. Corporate Social Responsibility Preferences in South Africa. Sustainability. 2022; 14(7):3792. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14073792

Chicago/Turabian StyleCheruiyot-Koech, Roselyne, and Colin David Reddy. 2022. "Corporate Social Responsibility Preferences in South Africa" Sustainability 14, no. 7: 3792. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14073792

APA StyleCheruiyot-Koech, R., & Reddy, C. D. (2022). Corporate Social Responsibility Preferences in South Africa. Sustainability, 14(7), 3792. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14073792