Abstract

The purpose of this research is to examine how the local community views the local school and higher education from the viewpoint of school leaders. Learning ‘using’ technologies has become a global phenomenon. The Internet is often seen as a value-neutral tool that potentially allows individuals to overcome the constraints of traditional elitist spaces and gain unhindered access to learning. Additionally, the study looks at the peculiarities of rural regions that are sparsely inhabited. The data came from a survey of 1270 Chinese school administrators. According to school leaders, local schools and higher education often score best in major cities and lowest in sparsely populated rural towns, revealing considerable disparities across the four categories of international urban regions. The articles also disclose certain information about sparsely populated rural places, such as a different sort of expectation of the local school, but also its worth, and establish a positive relationship between the school and the community. School staff have likewise expressed low expectations for the local school. These findings relate to continuing conversations in Asian nations about school leadership and education. The national governments and nongovernmental agencies who fund educational endeavors in developing countries have advocated the use of new technologies to reduce the cost of reaching and educating large numbers of children and adults who are currently missing out on education. This paper presents an overview of the educational developments in open, distance, and technology-facilitated learning that aim to reach the educationally deprived populations of the world. It reveals the challenges encountered by children and adults in developing countries as they attempt to access available educational opportunities.

1. Introduction

There are many different local school settings across the world, each with its own set of circumstances for school leaders to operate in. Successful school leadership has been related to the ability to comprehend and familiarize leadership to the particular environment, this does not [1]; however, imply that school leaders should take a different strategy in each case [2]. As a result, the emphasis of this paper is on school leaders in rural regions, an area of leadership research that has gotten little attention in the international and Chinese contexts in the past. Although this paper refers to technology-enhanced learning developments in developing countries, it by no means assumes that all developing nations have homogenous characteristics, social problems, and issues. These countries differ in their political circumstances, the history of their educational developments, culture, language, religion, gender issues, population size, resources, and the contemporary influx of technology. Each country has developed different forms of open and distance learning alternatives to meet the demand for education. Nonetheless, the key challenges all these nations face in trying to reach the masses and address issues of poverty and educational access make it worthwhile to compare their situations and strategies.

After reviewing the available literature on rural school leadership, Theoharis identified the primary challenges faced by rural school leaders [3]. Even though they are held to the same accountability requirements as their counterparts in bigger cities, rural school leaders typically lack administrative assistance and basic resources when it comes to school accountability and improvement efforts [4]. In addition, because of poverty and families’ socioeconomic standards, these school leaders deal with a broader variety of chores and prospects in the leadership from such locality. Grissom et al. found that principals with less experience and education operate in the most difficult environments—in this instance, a substantial percentage of low-income, non-white, and/or low-income students [5]. Moreover, some parents are worried about their experience towards school learning, particularly those who are less educated which, according to Bahmani et al., may lead to less engagement among schools and parents [6]. Many studies have elaborated that school administrators in rural locations devote more effort to developing strong community partnerships with local community members and groups [7]. Rural school leaders spend less time working with other school leaders due to the considerable distance between schools, the broad variety of tasks, and the habits of working alone, according to studies [8].

According to research on the background of state impact that matters, these leadership ideas are critical. School leaders handle relationships with many groups, both within and outside of the school in a hierarchical and networked fashion as leaders [9]. In China and other neighboring nations, school administrators must strike a balance between national leadership (national curriculum, education regulations), local political leadership (school board members are chosen via political elections), and supervisory leadership (political committees and department heads serving in the city). A continual engagement process based on varied power relationships builds trust and confidence, while also presenting risk and opportunity to school leaders [10]. One conundrum posed by these contextual differences is how to achieve educational equality in all schools, independent of their location, size, socioeconomic status, or other factors. The perspective of the overall purpose of education and building is also addressed in statements about these difficulties [11].

The previous study has revealed, for example, that contemporary globalization tendencies and “new public administration (NPM)” have produced an educational divide between rural and urban regions [12]. The problem of how to incorporate and integrate the local context into the leadership of school leaders was addressed in a recent study on the professional identity of Chinese school leaders [13]. The purpose of this article is to bring attention to the findings of earlier surveys, especially those involving school leaders in rural regions and how such surveys are performed in China.

As seen by the present corpus of Chinese research, some researchers have evaluated national data from a comparative viewpoint to discover the similarities and variances between school leaders in rural regions and other locations. In light of this, this article considers a rising number of researches on rural school leadership, most of which have been done in the United States, Canada, and Australia [14]. China, a sparsely populated nation with a long history of rural elementary schools, is an excellent example. In China, there are around 125 municipalities directly under the central government, with a population of fewer than 10,000 people, with 25 of them having a population of fewer than 5000 people [15]. However, Johnson’s work provides important insights into the participation and impact of youth in various rural and urban settings [16]. These earlier discoveries also addressed important issues of equality and power dynamics between cities and rural areas. One might argue that schools and their leaders play an important role in society in an age when the population of some places is declining and there is inequality between those who choose to live in big cities and those who prefer to stay in the countryside.

As a result, there are compelling justifications for paying more attention to community impressions of the local school and higher education, as well as school leaders’ experiences, particularly in rural locations. This article is based on data from a survey of Chinese school administrators that was conducted in June 2020. The purpose of this essay is to examine the local schools and community’s perspectives on further education from the viewpoint of a school leader. Another goal is to look at the peculiarities of rural regions that are sparsely inhabited. The analytical study was guided by the following research questions:

- What are school officials’ perspectives about continuing education in local schools and communities in each city?

- Are there any distinguishing features among school leaders in sparsely populated rural locations, and if yes, how can these disparities be explained?

The following is a breakdown of the article’s structure. First, the analytical work is described in more depth. The findings of both qualitative and quantitative data analysis are combined in a comprehensive report. A discussion and some conclusions conclude the article.

2. Research Methodology

2.1. Data Sample and Survey

The Ministry of Education of China provided email addresses for school leaders for the poll. According to the official figures, China presently employs three thousand and six hundred full-time school leaders in the research area. We have thought about how the responsibilities of school leaders would change in the Chinese context. Because they seldom have the chance to address specific questions on community leadership, temporary or appointed school leaders are dismissed. The school’s vice-principal has also been eliminated since, in China, they have no final accountability for matters that concern the school’s leaders (e.g., legal and financial considerations, for instance, budget, and salary determination). However, school officials from both public and private schools are concerned. The lack of significant differences between the different kinds of school ownership was one of the key arguments for combining and marketing them.

The poll was restricted to 3000 principals with this in mind. Following the first email, it became evident that the email address had not been fully updated; as a result, much effort was expended on the hunt for the “missing” school principal. New emails were sent to the heads of these schools. Following that, all school leaders received two reminders.

Notwithstanding these obstacles, the data obtained meets the article’s aim and goals as the 249 school leaders out of 290 local municipalities were represented, which counts the sample size to (n = 1270). The Chinese Ministry of Education defined four sorts of municipalities, and there was a good range amongst them (large city, city, rural areas, and sparsely populated rural areas). Moreover, the strength of the empirical data is that there was a wide range of age, number of years in the profession, school unit size, gender, and school ownership.

Some probable causes in the non-response analysis should be emphasized. The difficulties in acquiring updated e-mail addresses from the National Agency for Education have previously been mentioned. Another aspect is that Chinese school leaders change occupations more frequently than their regional counterparts, resulting in empty posts and the replacement of many school leaders are filled by part-time heads. Another issue is that some emails are caught by municipal spam filters, thus all reminders are addressed to the school directly, and 13 participants were dropped from the research due to missing data.

2.2. Quantitative Data Analysis Method

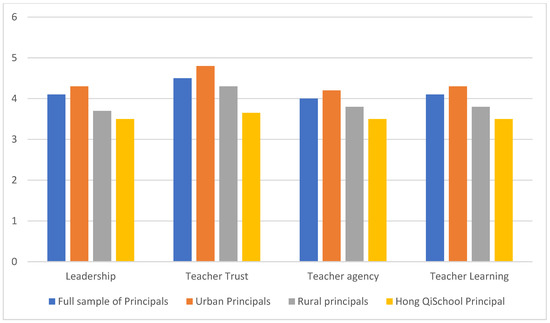

We start via way of means of summarizing findings drawn from posted quantitative analyses in comparison to the overall performance of city and rural colleges that participated in this survey. The cause of imparting those findings is to emphasize the quantity to which the agricultural principals embraced the function of studying-focused management and the character in their effect at the expert studying in their teachers. These analyses employed descriptive statistics, t-tests, confirmatory evaluation, and structural equation modeling (SEM). Because the information of those quantitative analyses had been offered elsewhere, within the modern-day paper, we summarized the quantitative effects in order to keep the area reserved for the qualitative evaluation. Our purpose within the qualitative segment of this survey was to expand an in-depth, holistic description of how one major replied to the demanding situations of the main trainer studying in a rural Chinese faculty. Yin (2002) asserted that ‘You might use the case examine technique due to the fact you intentionally desired to cowl contextual conditions-believing that they are probably fairly pertinent to your phenomenon of examination. Thus, the case examine technique is regarded as appropriate for the ambitions of this research. Data had been analyzed via way of means of thematic evaluation. After analyzing the interview transcripts numerous times, statistics had been diagnosed in terms of key topics pronounced on this survey: context and management, trainer trust, trainer agency, studying-focused management and trainer expert studying. We searched the statistics-set for patterns, commonalities, and contradictions in terms of how principals enacted their management function to guide trainer studying and faculty development. For the purposes of this example survey, we organized the evaluation of the statistics into phrases of four dimensions of studying-focused management, as described in this examination. We employed statistics triangulation to ‘make a contribution to verification and validation of qualitative evaluation via way of means of checking the consistency of findings generated via way of means of one-of-a-kind statistics series techniques, and checking the consistency of various statistics reassertion withinside the equal technique’. We relied on one-of-a-kind statistics triangulation.

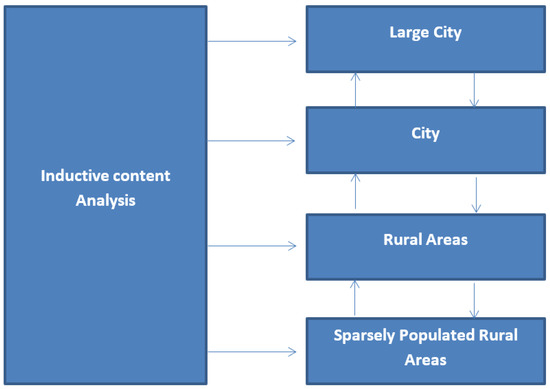

2.3. Data Analysis (Qualitative)

The Chi2 analysis was augmented and enhanced by the qualitative data analysis. With the help of tools for analysis of the data qualitatively, free-text responses were imported and structured (NVivo 12). To organize the analytical process, an analysis framework was devised (see Figure 1). Initially, the purpose of the research was to uncover some passages that demonstrate the opinions of school leaders concerning continuing education in schools and communities. The local administrative system of China splits these categories into four sorts of municipalities (big cities, towns, rural regions, and poorly populated rural areas) (large cities, towns, rural areas, and sparsely populated rural areas). Compare and evaluate quotations and quotes of school leaders in four metropolitan kinds were used to discover if there were variations between school leaders in sparsely populated rural regions, and if so, how to explain these differences. As a result, the analysis of the qualitative data focused on analyzing the variances revealed by the quantitative analyses to answer research question two.

Figure 1.

Comparison of urban, rural, Hong Qi principals on the four constructs.

The following snippets and quotations have been chosen as indicative instances and comparison cases to improve the quantitative analysis. It is significant to mention that each unknown school leader is one-of-a-kind, thus it only shows on the results page once.

2.4. School Sample

The school sample examined targeted patterns of 31 public number one and secondary colleges positioned in 3 regions of mainland China that embody an extensive variety of city and rural areas (Shanghai, Ningxia and Hailing). The college pattern became a practical comfort pattern. The pattern became practical from the observation that the choice of colleges included variants on numerous key variables consisting of college level and geographic location (i.e., city/rural). The traits of the trainer pattern (see Table 1) were usually consultant of the populace of China’s instructors on gender, rank and experience. Consistent with the literature, rural instructors in this appear much less certified compared with city instructors. The city cohort held better stages of tutorial attainment and expert rank. More specifically, the agricultural cohort was constructed from a decreased percentage of excessive expert rank instructors and a bigger percentage of instructors with at best, an excessive college degree. This additionally defined the lecturers within the case by looking at the college. The qualitative part of this study analyzed the gathering of quantitative records. In this segment of analysis, we recognized numerous colleges within the complete pattern of 38 schools, with 1 that confronted very one-of-a-kind college development challenges. We accumulated qualitative cases to analyze records in those colleges over a length of numerous years. The case analyzed, provided in this paper, specializes in one principal, Principal Liu, from Hong Qi Primary School, a rural college in Southwest China. Principal Liu tested a sample of vulnerable learning-concentrated management that become consistent with the alternative rural principals.

Table 1.

The characteristics of teacher sample and population.

Using different methods to measure and calculate ANOVA:

Statistical analysis was performed using ANOVA and the statics. Analysis of variance (ANOVA) is a statistical technique that is used to check if the means of two or more groups are significantly different from each other. “ANOVA” checks the impact of one or more factors by comparing the experientially means of different data. All results of the quantitative variables’ statistical module were reported either as means and standard deviation or frequency (percentage) (%). ANOVA was applied to assess if there was a significant association between categorical variables data (see Table 2). There was no association between the mean intrusive scale score and other demographic factors and was considered to be statistically significant (p > 0.025). There was also no association between the mean avoidance scale score and any demographic factors (p > 0.025).

Table 2.

ANOVA factor and analysis.

3. Results

This part is divided into four affirmations, and school leaders must score their agreement with the facts on a scale of 1 to 6. There are three elements to the findings (views about local schools, views on continuing education, and job opportunities after primary school). The qualitative analyses findings are utilized to further analyze and expand the Chi2 analysis findings, as well as the two research questions that are given (see Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Scheme of analysis.

3.1. Attitudes towards the Local School and Education

The first research examines school leaders’ perceptions of local schools’ perspectives and educational opportunities in the community. The following graph depicts the distribution of school leaders’ estimates (see Table 3).

Table 3.

The importance of education in the local society is valued differently by principals.

As indicated in Table 1, school leaders in sparsely populated rural regions pay less attention to community education than school leaders in the other three kinds of cities. There is a significant association between the kind of municipality and the assessed worth of school leaders, according to Chi2 analysis, X2 (18, N = 1270) = 174.70, p. 001. Cramer V = 35, indicating that the observed value based on column and row correlation is moderate. Education was less valued in remote and sparsely inhabited regions (p < 0.005), according to a post hoc test.

The qualitative study indicates a more in-depth Chi2 analysis of the features of sparsely populated rural regions than the other three categories of cities. More precisely, municipal school officials did not imply that local schools had high expectations, at least in terms of education, or that education was valued in the community. Some school officials expressed the attitudes in the local community as “rural culture”, “small municipality mentality”, “industrial community mentality”, and “poor education culture” in their explanations.

However, poll findings show that local school and continuing education expectations are low and that there may be issues. Parents have high expectations of local schools, even though teaching levels in these places are often poor. In a town with a small population, Qin, a school head, clarified:

“I work in a small municipality in which there is only one F-6 school. Parents have an expectation to be involved and decide about many things in the school, especially if things are not good. Therefore, I have to work a lot to promote good forms of collaboration with them”.

As a result, school officials in sporadically populated rural regions emphasized the significance of local schools in the tiny municipality. Furthermore, if education is not a high priority, some school officials think that schools play an important role in maintaining community cohesion. As a result, expectations for the local schools are different from those for other sorts of municipalities. This is how Ban said it:

“There is a culture in the municipality that the social (mission) of the school is more important than the education itself. Many people also know how it should be”.

Other features of sparsely inhabited rural regions were discovered by the investigations. These school leaders, for example, underlined that the town had a “strong cohesiveness” and a custom of “everyone knows everyone”. Consequently, as a leader of a school, you are acquainted with a wide range of individuals, including parents, legislators, and members of the local business community, all of whom have particular expectations from the leader of the schools and municipal schools. Certain leaders of the schools portrayed these background variables in a positive light, arguing, for example, that communication channels are becoming shorter, making it easier to find common ground on a variety of subjects. On the contrary, some leaders of other schools pointed out that these demands may be taxing. As shown by Qi, such statements were not observed by other municipalities school leaders:

“The fact that I live and work in the same small community makes me feel greater pressures from the surrounding community. Here, I cannot resign and seek another school leadership job because then, I let the whole village down”.

To recap the first section, school leaders in sparsely populated rural regions pay less attention to community education than school leaders in the other three kinds of cities. Similar results in qualitative study were supported by school administrators, who referred to local communities’ “country culture”, “small-town mentality”, and “industrial society mentality”. Most importantly, the other municipality kinds lacked equivalent vocabulary and explanations. Even though administrators had low expectations for local schools and education in terms of teaching, they underlined that local schools may play an essential role in the community. As a result, expectations are huge.

Although their personalities are considerably diverse and school leaders just use two adjectives to describe them as excellent or terrible, their influence on local schools and education may be enormous.

3.2. Perceptions of Higher Education

Another investigation focused on school administrators’ predictions about whether pupils would move on to higher education. This study also looked at how school officials viewed students who planned to continue their education at the university level (see Table 4). The following graph depicts the dispersion of school principals’ estimates.

Table 4.

Estimation by the school principal on students’ continuation to the level of higher secondary level.

The table demonstrates an important nexus between the type of municipality and the school leadership estimate, X2 (18, N = 1270) = 89.82, p < 0.001. In more detail, school leaders in large towns and cities estimate that students are more likely to continue their university studies than school leaders in rural areas and sparsely populated rural areas (p < 0.005). It is important to mention that roughly a third of school administrators could not predict how many pupils went on to higher education. Cramer’s V = 0.16, which indicates a modest effect size, was used to quantify the association in this study. Principals in remote and poorly inhabited regions believed that only a small number of children will progress to upper secondary school (p < 0.005), according to post hoc assessments.

Table 5 reveals that the kind of municipality and the evaluation of school leaders have a statistically significant relationship, X2 (18, N = 1270) = 89.82, p < 0.001. School leaders in big cities, in particular, feel that students in sparsely inhabited rural regions are more motivated to attend college than school officials in sparsely populated rural areas (p < 0.005). In a similar vein to the last question, over 30% of school administrators had no idea how many kids will go on to university.

Table 5.

Estimation by the school principal on students’ continuation to university study.

The overall image produced by the analysis was mostly confirmed by the qualitative data analysis. To begin with, none of the city municipal school officials said that few pupils enter higher secondary school, and university courses are deemed unimportant, or that students find work in their local community shortly after finishing obligatory education. Particularly, this is true, that leaders of schools work in “adversarial” environments. This is not to say that these kinds of attitudes do not exist in these communities; they just do not seem to be exclusive to these two sorts of municipalities.

The qualitative investigation revealed data about the features of the leaders of schools in sporadically rural populated regions that might help people better comprehend the differences between the different kinds of municipalities. Some school officials said that there is a “lack of an education culture” and that there is “scepticism regarding education” generally, especially about university courses. Such instances stand in stark contrast to the views of school leaders in other sorts of municipalities, most notably in the city and big city groups. Parents and the surrounding community, according to school officials, had great expectations for the school to provide children with a solid knowledge basis for their growth, as well as for students to get excellent grades to join the “proper” high school, as well as private schools, particularly in the two city categories. Quinn was a perfect example of what was expected of him:

“(We have) strong parents who have both the financial and the educational status, which can be a challenge. Many times … they can be burdensome if they receive a negative answer when it comes to a holiday request or low grades”.

The research also found that in sparsely populated rural locations, attitudes toward higher education are unfavorable, not only from the local communities’ members’ and parents’ perspectives. On the subject of what distinguishes the schools and the town, one school head, Li, responded:

“The lack of academic traditions in the local community, but also among the school staff. There is also a lack of knowledge based on facts among school staff and parents”.

The quote seems to be significant in various ways. More specifically, the remark implies that cynicism regarding higher education is not limited to the surrounding population; school staff may also contribute to such beliefs. It is worth noting that no quotations with comparable features were identified from other urban school administrators. In contrast to the other three local school leaders, school leaders emphasized the low level of formal education of teachers and staff, as well as the difficulty in obtaining suitable faculty.

Finally, it is worth noting that school administrators actively worked to influence students’ attitudes regarding higher education. An official from school also indicated a wish to stimulate students and teenagers by encouraging them to pursue more education, “I would want to encourage an enhanced interest in studies in general”, Han, for example, argued that “students should be able to appreciate the benefits of additional study”. Xu, a leader from another school, expressed her desire to “see a stronger future for our young people to remain in the municipality—possibilities to study further (without having to migrate)”. Kim in a similar spirit, said, “I want the school to be the basis that helps young people remains in the countryside, or choose to go back”.

To summarize the second section, school administrators in densely populated urban regions feel that more pupils go on to high school than school officials in sparsely inhabited rural areas. Furthermore, school officials in major cities and towns feel that students in sparsely populated rural regions continue to study more than students in large cities and towns. In terms of the qualitative analysis and features of sparsely populated rural locations, these school leaders said that these cities “lack education and culture” and that “widespread cynicism about education” exists, particularly in university courses. As previously said, some cities’ educational leaders lack such words and explanations. These values also stand in stark contrast to school leaders in both city groupings, who often stress parents’ and communities’ high expectations for teaching quality and student progress.

3.3. Possibilities for Employment after Elementary School

The third section of the study examines school leaders’ perceptions about the likelihood of obtaining work after graduating from primary school. The outcome is as follows (see Table 6):

Table 6.

Estimation by principals regarding the likelihood of finding work after elementary school education.

The results illustrate the association between the kind of municipality and the perceived value of school leadership X2 (18, N = 1270) = 41.10, p < 0.001. Cramer V = 0.16, on the other hand, indicates that this association is relatively weak. School administrators in remote regions believed that their prospects of obtaining work after school were poor (p < 0.005), according to post-mortem examinations. In addition, the same trend as the previous issue was discovered, with roughly 30% of school leaders unable to assess the likelihood of obtaining work after graduation from elementary school.

Thus, the qualitative research revealed some information about sparsely populated rural towns and dived further into the topics of work chances following obligatory education and the link between additional studies and employment. Some school administrators, for example, have claimed that creating a positive connection between the school and local community actors may assist children to find work once they finish primary school. School leaders in other towns, particularly big cities and metropolitan areas, aim for greater in-depth collaboration between schools and local corporations, such as via internships, study excursions, and other means.

Numerous school leaders also remarked that jobs are becoming scarcer, particularly in sparsely populated rural regions, emphasizing the significance of education and the presence of local institutions. Some school authorities have said that there is no inconsistency between students having an academic education and the continuous expansion of local enterprises, such as those in the forestry or steel sectors, as Wang explains:

“(I wish) that the attitude toward education is increased and that the students are allowed to work in the village. (I wish) also that the inhabitants, in line with increased educational level, develop the business sector in more areas and also in sustainable development”.

To summarize the last section, the Chi2 analysis demonstrates a difference between municipal and school leadership estimations; however, the correlation is lower than in earlier research. Nonetheless, qualitative data analysis might provide some insights into the peculiarities of sparsely inhabited rural places. Many school administrators have noted that, in comparison to other towns, there is a solid link between schools and local community actors, which may assist youngsters in obtaining employment once they graduate from elementary school. Furthermore, school administrators stated that staffing is dropping even in sparsely populated rural regions, emphasizing that young people may need to complete their education to survive in these locations.

4. Discussion

Two research issues were addressed in the above-mentioned analysis. From the standpoint of a school leader, the first inquiry focused on pre-existing impressions about the higher education in the school located in the municipality. The second inquiry was to determine if school leaders in sparsely populated rural locations share particular features, and if yes, how such variances may be described. The findings of the study indicated considerable disparities in perceptions of local schools and continuing education across the four Chinese municipalities constituted under the local government system. According to participating school leaders, local schools and further education are regarded most highly in big cities and least highly in less populated rural communities. Furthermore, the data revealed that these school leaders believed their chances of finding work after high school were better than those of their classmates from other municipalities, even though the association was weak. Another interesting finding is that a significant proportion of school leaders struggled to answer the questions of the survey. This suggests that the leaders of schools in China may only have a hazy understanding of the local situation and how it influences their leadership. This seems to be an issue, not least since effective management is based on the indigenous environment [17].

In terms of the features of school leaders in sparsely populated rural locations and how to interpret these qualities, qualitative research mostly validates the Chi2 analysis’ findings. Although school administrators have low expectations for local schools and teacher education, they believe that local schools may play an essential role in the community. As a result, parents’ expectations and impressions differ from those of other kinds of communities. School authorities said that their personnel had poor expectations of local schools and did not trust supplementary schooling. Some school authorities have claimed that their goal is to persuade students and teenagers to pursue additional education. When it comes to career chances outside of primary school, school administrators in sparsely populated rural regions say that building a positive connection between the school and community members may assist students to obtain jobs once they finish primary school. However, when jobs become rare even in rural regions, some school officials think that more education may be required to maintain the kids in these communities since the surviving firms require well-educated personnel.

The educational level of a person might have an impact on their views and expectations about their local school and higher education.

These results contribute to the development of a knowledge system regarding school leadership in China and throughout the globe. These differences become crucial to explore in light of recent studies demonstrating the necessity of recognizing and developing school leadership anchored in the local environment [18]. Recent research on the identity of Chinese school leaders has underlined the need to incorporate the local context into school leadership [19]. In this regard, the Chinese Ministry of Education has separated the national training plan into three sections: education law, governance, regulation; quality; and school leadership. The updated strategy emphasized school legislation, resource allocation, methodological work, quality, and governance concerns. Without diminishing the relevance of in-depth knowledge in these areas, we feel that it is still necessary to underline that school leadership is context-dependent, even in China, and that for successful leadership and school reform, the local context provides a solid beginning point. In light of the findings of this paper, school administrators in sparsely populated rural regions may find this to be even more critical.

A key finding in terms of context is that parents’ expectations and respect for local schools are low, which connects with their expectations and regard for local schools, though it has nothing to do with educational training and/or school reforms. According to Johnsen, & Bele (2013), the parents who are not well educated are frequently more apprehensive about their school and educational experiences, which may influence parent-school cooperation [20]. The features of school leadership in sparsely populated rural locations established in the prior study are revealed in these official findings. The results of the study are also in line with prior research on rural school leadership, which revealed that these school leaders spend more time cultivating strong community links [21]. In this instance, school officials repeatedly said that they put a great deal of effort into creating connections with parents. Simultaneously, they must contend with the reality that parents in these places want to be involved in and make choices on school issues that have little to do with pedagogy or school growth. In light of this, these school leaders must strive toward a change in parental engagement and expectations that encompass children’s learning and development, as well as other areas in which they are expected to participate [22].

It is also necessary to put the findings of this research into context, based on prior discussions on education’s overall purpose and mission in the Asian countries [23]. As a result, the differences shown across the various kinds of municipalities give valuable information for future debates, such as equivalency and the right to decent education, irrespective of the nation’s geography, school’s locality, financial situations, and similar things. There may be difficulties with fairness and whether all students in the Chinese education system have equal opportunity if parents (and school employees) in sparsely populated rural regions have low expectations for local schools and continued education. However, as many school leaders have pointed out, there is no essential inconsistency between continuing education and the right to stay in the nation; on the contrary, extra education may be necessary after school graduation.

As a result, concerns regarding the kind of information that children and teenagers desire and seek in these areas are part of a bigger discussion. In light of current NPM and globalization trends, which have a detrimental influence on rural regions, it is time for the debate on education’s motive and aims, as well as the notion of consciousness. In this type of conversation, it is important to emphasize not just practical-aesthetic teaching topics, but also other difficult-to-measure and evaluate teaching subjects, such as philosophy and history. We feel that based on past research, not only the value of education but also the importance of nurture should be assessed [24]. This conversation, in our view, might pave the way for leaders of more dynamic, community-based schools. Parents and school leaders may have important discussions about the responsibilities and functions of local schools, as well as how extra education might assist in providing a valuable platform for the community’s children and youth.

After that, it is important to point out some of the study’s shortcomings. In terms of methodology and analysis, it is important to emphasize that the article’s findings are “exclusively” based on the experiences of Chinese school directors and should thus be viewed with caution. As a result, in future case studies, to acquire a wider and (potentially) more complicated image of local schools and higher education, it is vital to include parents and other community people, particularly in sparsely populated rural regions. Furthermore, the importance of city categorization should be highlighted. It should be highlighted that the applicable categorization, for example, is fairly wide, which might lead to certain subtleties in the study being disregarded. This categorization seems to be more accurate than other classifications in the Chinese context, based on the presentation and comprehension of the idea of “rural” regions and/or areas in the international context.

5. Conclusions

The findings of this research show that sentiments about local schools and community continuing education varied statistically significantly between cities and towns. According to participating school leaders, local schools and further education are regarded most highly in big cities and least highly in less populated rural communities. Regarding other aspects of sparsely populated rural regions, school leaders underlined that, even though educational prospects for local schools and education were low, local schools, and education were still important, and that the local school may nevertheless play an important role in the community as a whole. Even if parents’ expectations and prospects differ little, this remains true. School workers also indicated skepticism regarding extra schooling and stated low hopes for local institutions. Officials from the school have also indicated that they want to inspire students and youngsters by encouraging them to pursue higher education. They also said that a positive connection has been built between the school and community members, which may assist children in finding employment once they graduate from elementary school. Nonetheless, school officials noted that even in rural regions, employment is becoming scarce. Further education, according to some school officials, is a must for youth to remain in such areas since surviving businesses require well-educated workers. These results contribute to current educational research institutes in China and internationally, as well as a larger understanding of the general purposes of education, nurturing, and power interactions between cities and towns together with the countryside.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, L.L. and D.Y.; writing—original draft preparation, L.L.; writing—review and editing, D.Y.; formal analysis, K.Y. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data used to support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Baecher, L.; Knoll, M.; Patti, J. Addressing English language learners in the school leadership curriculum: Mapping the terrain. J. Res. Leadersh. Educ. 2013, 8, 280–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theoharis, G. Social justice educational leaders and resistance: Toward a theory of social justice leadership. Educ. Adm. Q. 2007, 43, 221–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tekleselassie, A.A.; Villarreal, P., III. Career mobility and departure intentions among school principals in the United States: Incentives and disincentives. Leadersh. Policy Sch. 2011, 10, 251–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grissom, J.A.; Nicholson-Crotty, S.; Harrington, J.R. Estimating the effects of No Child Left Behind on teachers’ work environments and job attitudes. Educ. Eval. Policy Anal. 2014, 36, 417–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhamani, S.; Makhdoom, A.Z.; Bharuchi, V.; Ali, N.; Kaleem, S.; Ahmed, D. Home learning in times of COVID: Experiences of parents. J. Educ. Educ. Dev. 2020, 7, 9–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, L.L. Cadres, temple and lineage institutions, and governance in rural China. China J. 2002, 48, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Darling-Hammond, L.; Flook, L.; Cook-Harvey, C.; Barron, B.; Osher, D. Implications for educational practice of the science of learning and development. Appl. Dev. Sci. 2020, 24, 97–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Meier, K.J.; O’Toole, L.J., Jr. Public management and educational performance: The impact of managerial networking. Public Adm. Rev. 2003, 63, 689–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tschannen-Moran, M. Fostering teacher professionalism in schools: The role of leadership orientation and trust. Educ. Adm. Q. 2009, 45, 217–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sjöström, J.; Eilks, I. Reconsidering different visions of scientific literacy and science education based on the concept of Bildung. In Cognition, Metacognition, and Culture in STEM Education; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 65–88. [Google Scholar]

- Grimaldi, E.; Hall, D.; Serpieri, R. New Public Management and the Reform of Education; Gunter, H., Ed.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Alhosani, S.A. The Influence of Irtiqa’A Inspectorate Program on School Leaders’ Professional Identity and Their Operational Practices in Abu Dhabi Schools. Bachelor’s Thesis, United Arab Emirates University, Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Wolf, J.; Moser, S.C. Individual understandings, perceptions, and engagement with climate change: Insights from in-depth studies across the world. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Clim. Chang. 2011, 2, 547–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, C.; Liu, L.; Guo, W.; Yang, A.; Ye, C.; Jilili, M.; Ren, M.; Xu, P.; Long, H.; Wang, Y. Prediction of epidemic spread of the 2019 novel coronavirus driven by spring festival transportation in China: A population-based study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 1679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Johnson, K.A. Women, the Family, and Peasant Revolution in China; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Lewis, J.L.; Sheppard, S.R. Culture and communication: Can landscape visualization improve forest management consultation with indigenous communities. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2006, 77, 291–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hart, R.A. Children’s Participation: The Theory and Practice of Involving Young Citizens in Community Development and Environmental Care; Routledge: London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Truong, T.D.; Hallinger, P.; Sanga, K. Confucian values and school leadership in Vietnam: Exploring the influence of culture on principal decision making. Educ. Manag. Adm. Leadersh. 2017, 45, 77–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lynch, D.; Smith, R.; Provost, S.; Madden, J. Improving teaching capacity to increase student achievement: The key role of data interpretation by school leaders. J. Educ. Adm. 2016, 54, 575–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnsen, Å.A.; Bele, I.V. Parents of students who struggle in school: Are they satisfied with their children’s education and their own involvement. Scand. J. Disabil. Res. 2013, 15, 89–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Day, C.; Gu, Q.; Sammons, P. The impact of leadership on student outcomes: How successful school leaders use transformational and instructional strategies to make a difference. Educ. Adm. Q. 2016, 52, 221–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, J.J.; Deng, R.; Zhang, Q.; Cai, J.; Li, M. Research on recognition of gas saturation in sandstone reservoir based on capture mode. Appl. Radiat. Isotopes. 2021, 178, 109939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kennedy, T.J.; Odell, M.R.L. Engaging students in STEM education. Sci. Educ. Int. 2014, 25, 246–258. [Google Scholar]

- Borrero, N. Nurturing students’ strengths: The impact of a school-based student interpreter program on Latino/a students’ reading comprehension and English language development. Urban Educ. 2011, 46, 663–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).