Fostering Work Meaningfulness for Sustainable Human Resources: A Study of Generation Z

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Literature Review and Hypotheses Development

2.1. Generation Z in the Age of Digital Disruption

2.2. Work Meaningfulness and Employee Retention

2.3. Job Characteristics

3. Research Methodology

3.1. Sample and Procedures

3.2. Measures

3.2.1. Job Characteristics

3.2.2. Work Meaningfulness

3.2.3. Intention to Stay

3.2.4. Controls

4. Results

4.1. Validity and Reliability Measures

4.2. Hypotheses Testing

5. Discussion

5.1. Theoretical Implications

5.2. Practical Implications

5.3. Limitations and Future Research

6. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Pratt, M.G.; Ashforth, B.E. Fostering meaningfulness in working and at work. In Positive Organizational Scholarship: Foundations of a New Discipline; Cameron, K.S., Dutton, J.E., Quinn, R.E., Eds.; Berrett-Koehler Publishers, Inc.: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2003; pp. 309–327. [Google Scholar]

- Rosso, B.D.; Dekas, K.H.; Wrzesniewski, A. On the meaning of work: A theoretical integration and review. Res. Organ. Behav. 2010, 30, 91–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Fabio, A. The psychology of sustainability and sustainable development for well-being in organizations. Front. Psychol. 2017, 8, 1534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Bailey, C.; Yeoman, R.; Madden, A.; Thompson, M.; Kerridge, G.A. Review of the empirical literature on meaningful work: Progress and research agenda. Hum. Resour. Dev. Rev. 2019, 18, 83–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, T.Y.; Shaw, J.D. Turnover rates and organizational performance: A meta-analysis. J. Appl. Psychol. 2013, 98, 268–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- World Economic Forum. 3 Rules for Engaging Millennial and Gen Z Talent in the Workplace. Available online: https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2020/01/millennial-gen-z-talent-workplace-leadership/ (accessed on 14 September 2021).

- Seemiller, C.; Grace, M. Generation Z: A Century in the Making; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Mahmoud, A.B.; Fuxman, L.; Mohr, I.; Reisel, W.D.; Grigoriou, N. We aren’t your reincarnation! Workplace motivation across X, Y and Z generations. Int. J. Manpow. 2021, 42, 193–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pichler, S.; Kohli, C.; Granitz, N. DITTO for Gen Z: A framework for leveraging the uniqueness of the new generation. Bus. Horiz. 2021, 64, 599–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weeks, K.P.; Schaffert, C. Generational Differences in Definitions of Meaningful Work: A Mixed Methods Study. J. Bus. Ethics 2019, 156, 1045–1061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cogin, J. Are generational differences in work values fact or fiction? Multi-country evidence and implications. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2012, 23, 2268–2294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Twenge, J.M.; Campbell, S.M.; Hoffman, B.J.; Lance, C.E. Generational differences in work values: Leisure and extrinsic values increasing, social and intrinsic values decreasing. J. Manag. 2010, 36, 1117–1142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, H.-S.; Yoon, H.-H. Generational effects of workplace flexibility on work engagement, satisfaction, and commitment in South Korean deluxe hotels. Sustainability 2021, 13, 9143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popaitoon, P.; Wademongkolgone, M.; Kongchan, A. Generational differences in person-organization value fit and work-related attitudes. Chulalongkorn Bus. Rev. 2016, 147, 107–137. [Google Scholar]

- Sturges, J.; Conway, N.; Guest, D.; Liefooghe, A. Managing the career deal: The psychological contract as a framework for understanding career management, organizational commitment and work behavior. J. Organ. Behav. 2005, 26, 821–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allan, B.A.; Batz-Barbarich, C.; Sterling, H.M.; Tay, L. Outcomes of meaningful work: A meta-analysis. J. Manag. Stud. 2019, 56, 500–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Humphrey, S.E.; Nahrgang, J.D.; Morgeson, F.P. Integrating motivational, social, and contextual work design features: A meta-analytic summary and theoretical extension of the work design literature. J. Appl. Psychol. 2007, 92, 1332–1356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Goh, E.; Baum, T. Job perceptions of Generation Z hotel employees towards working in COVID-19 quarantine hotels: The role of meaningful work. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. 2021, 33, 1688–1710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smaliukiene, R.; Bekesiene, S. Towards sustainable human resources: How generational differences impact subjective wellbeing in the military? Sustainability 2020, 12, 10016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, M.; Bonn, M.A.; Han, S.J. Generation Z’s sustainable volunteering: Motivations, attitudes and job performance. Sustainability 2018, 10, 1400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Popaitoon, S.; Popaitoon, P. What are work values of new workforce in digital economy? Generation Z and implications for human resource management. J. Bus. Adm. 2020, 168, 18–37. [Google Scholar]

- Farrell, W.C.; Phungsoonthorn, T. Generation Z in Thailand. Int. J. Cross Cult. Manag. 2020, 20, 25–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michaelson, C.; Pratt, M.G.; Grant, A.M.; Dunn, C.P. Meaningful work: Connecting business ethics and organization studies. J. Bus. Ethics 2014, 121, 77–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hackman, J.R.; Oldham, G.R. Motivation through the design of work: Test of a theory. Organ. Behav. Hum. Perform. 1976, 16, 250–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mannheim, K. The problem of a sociology of knowledge. In Essays on the Sociology of Knowledge; Harcourt, Brace and World: New York, NY, USA, 1952; pp. 134–190. [Google Scholar]

- Parry, E.; Urwin, P. Generational differences in work values: A review of theory and evidence. Int. J. Manag. Rev. 2011, 13, 79–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edmunds, J.; Turner, B.S. Global generations: Social change in the twentieth century. Br. J. Sociol. 2005, 56, 559–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Statista Research Department. Daily Social Media Usage Worldwide 2012–2020. Available online: https://www.statista.com/statistics/433871/daily-social-media-usage-worldwide/ (accessed on 22 December 2021).

- Gen Z & Millennials Use Social Media Differently. Available online: https://www.ypulse.com/article/2021/02/22/gen-z-millennials-use-social-media-differently-heres-x-charts-that-show-how/ (accessed on 22 December 2021).

- Adecco. Millennials vs. Gen Z: Key Differences in the Workplace. Available online: https://www.adeccousa.com/employers/resources/generation-z-vs-millennials-infographic/ (accessed on 20 August 2021).

- Turner, A. Generation Z: Technology and social interest. J. Individ. Psychol. 2015, 71, 103–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WARC. Pandemic Highlights Thailand’s Generational Differences. Available online: https://www.warc.com/newsandopinion/news/pandemic-highlights-thailands-generational-differences/44059 (accessed on 22 December 2021).

- Yamamoto, H. The relationship between employee benefit management and employee retention. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2011, 22, 3550–3564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Work Institute. Retention Report. Available online: https://info.workinstitute.com/hubfs/Retention%20Reports/2021%20Retention%20Report/Work%20Institutes%202021%20Retention%20Report.pdf (accessed on 1 October 2021).

- Lysova, E.I.; Allan, B.A.; Dik, B.J.; Duffy, R.D.; Steger, M.F. Fostering meaningful work in organizations: A multi-level review and integration. J. Vocat. Behav. 2019, 110, 374–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deloitte. Talent 2020: Surveying the Talent Paradox from the Employee Perspective. Available online: https://www2.deloitte.com/content/dam/Deloitte/mx/Documents/about-deloitte/Talent2020_Employee-Perspective.pdf (accessed on 2 September 2021).

- Grant, A.M. The significance of task significance: Job performance effects, relational mechanisms, and boundary conditions. J. Appl. Psychol. 2008, 93, 108–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dachner, A.M.; Ellingson, J.E.; Noe, R.A.; Saxton, B.M. The future of employee development. Hum. Resour. Manag. Rev. 2021, 31, 100732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Deci, E.L.; Ryan, R.M. The ‘what’ and ‘why’ of goal pursuits: Human needs and the self-determination of behavior. Psychol. Inq. 2000, 11, 227–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frankl, V.E. Man’s Search for Meaning; Beacon Press: Boston, MA, USA, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Blau, P.M. Exchange and Power in Social Life; John Wiley and Sons: New York, NY, USA, 1964. [Google Scholar]

- Brislin, R.W. Applied Cross-Cultural Psychology; Sage Publications: London, UK, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Jeong-Yeon, L.; Podsakoff, N.P. Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J. Appl. Psychol. 2003, 88, 879–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunnally, J.C. Psychometric Theory, 2nd ed.; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Morgeson, F.P.; Humphrey, S.E. The Work Design Questionnaire (WDQ): Developing and validating a comprehensive measure for assessing job design and the nature of work. J. Appl. Psychol. 2006, 91, 1321–1339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- May, D.R.; Gilson, R.L.; Harter, L.M. The psychological conditions of meaningfulness, safety and availability and the engagement of the human spirit at work. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 2004, 77, 11–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Price, J.; Mueller, C. Handbook of Organizational Measurement; Pitman: Marshfield, MA, USA, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Oldham, G.R.; Fried, Y. Job design research and theory: Past, present and future. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. 2016, 136, 20–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez, F.G.; Ramos, K. An exploration of gender and career stage differences on a multidimensional measure of work meaningfulness. J. Career Assess. 2017, 25, 423–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, T.W.; Burch, T.C.; Mitchell, T.R. The story of why we stay: A review of job embeddedness. Annu. Rev. Organ. Psychol. Organ. Behav. 2014, 1, 199–216. [Google Scholar]

| Characteristics | n | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Male | 383 | 51.3 |

| Female | 363 | 48.7 |

| Education | ||

| Vocational | 30 | 4.0 |

| Bachelor’s | 713 | 95.6 |

| Master’s | 3 | 0.4 |

| Occupational Category | ||

| Accounting and finance | 279 | 37.4 |

| Computer and information technology | 113 | 15.1 |

| Engineering | 99 | 13.3 |

| Logistics | 54 | 7.2 |

| Sales | 84 | 11.3 |

| Administrative support | 96 | 12.9 |

| Other | 21 | 2.8 |

| Tenure | ||

| Less than 1 year | 31 | 4.2 |

| 1–2 years | 629 | 84.3 |

| More than 2 years | 86 | 11.5 |

| Measures | Factor Loadings | AVE | Cronbach’s α |

|---|---|---|---|

| Skill variety | 0.588 | 0.823 | |

| The job requires a variety of skills. | 0.798 | ||

| The job requires me to utilise a variety of different skills in order to complete the work. | 0.805 | ||

| The job requires me to use a number of complex or high-level skills. | 0.823 | ||

| Task significance | 0.556 | 0.778 | |

| The results of my work are likely to significantly affect the lives of other people. | 0.802 | ||

| The job itself is very significant and important in the broader scheme of things. | 0.756 | ||

| The job has a large impact on people outside the organisation. | 0.761 | ||

| Task identity | 0.545 | 0.773 | |

| The job involves completing a piece of work that has an obvious beginning and end. | 0.755 | ||

| The job provides me the chance to completely finish the pieces of work I begin. | 0.807 | ||

| The job is arranged so that I can do an entire piece of work from beginning to end. | 0.782 | ||

| Autonomy | 0.677 | 0.864 | |

| The job gives me a chance to use my personal initiative or judgment in carrying out the work. | 0.779 | ||

| The job allows me to make a lot of decisions on my own. | 0.863 | ||

| The job provides me with significant autonomy in making decisions. | 0.809 | ||

| Feedback | 0.587 | 0.808 | |

| The work activities themselves provide direct and clear information about the effectiveness of my job performance. | 0.627 | ||

| The job itself provides me with information about my performance. | 0.860 | ||

| The job itself provides feedback on my performance. | 0.830 | ||

| Work meaningfulness | 0.777 | 0.934 | |

| The work I do on this job is very important to me. | 0.822 | ||

| The work I do on this job is worthwhile. | 0.803 | ||

| The work I do on this job is meaningful to me. | 0.874 | ||

| I feel that the work I do on my job is valuable. | 0.815 | ||

| Intention to stay | 0.700 | 0.874 | |

| If you had to quit work for a while (for example, because of studying), you would return to this organisation. | 0.768 | ||

| I plan to stay in this organisation as long as possible. | 0.777 | ||

| If you were completely free to choose, you would prefer to continue working in this organisation. | 0.815 |

| Variables | M | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Skills variety | 3.72 | 0.75 | 0.77 | ||||||||

| 2 Task significance | 3.47 | 0.85 | 0.43 *** | 0.75 | |||||||

| 3 Task identity | 3.77 | 0.89 | 0.35 *** | 0.41 *** | 0.74 | ||||||

| 4 Autonomy | 3.53 | 0.86 | 0.49 *** | 0.41 *** | 0.51 *** | 0.82 | |||||

| 5 Feedback | 3.75 | 0.72 | 0.48 *** | 0.54 *** | 0.42 *** | 0.50 *** | 0.77 | ||||

| 6 Work meaningfulness | 4.08 | 1.14 | 0.38 *** | 0.40 *** | 0.31 *** | 0.41 *** | 0.36 *** | 0.88 | |||

| 7 Intention to stay | 3.64 | 1.12 | 0.23 *** | 0.32 *** | 0.31 *** | 0.29 *** | 0.28 *** | 0.62 *** | 0.84 | ||

| 8 Tenure | 1.69 | 0.77 | −0.03 | 0.05 * | −0.01 | 0.00 | −0.01 | 0.13 *** | 0.05 | - | |

| 9 Gender | 0.51 | 0.50 | 0.04 ** | −0.14 | −0.01 | 0.02 | 0.00 | −0.08 *** | 0.03 | 0.04 | - |

| 10 Occupation | 0.18 | 0.38 | 0.19 *** | 0.04 * | 0.08 *** | 0.61 *** | 0.03 * | 0.10 *** | 0.06 | 0.00 | 0.05 |

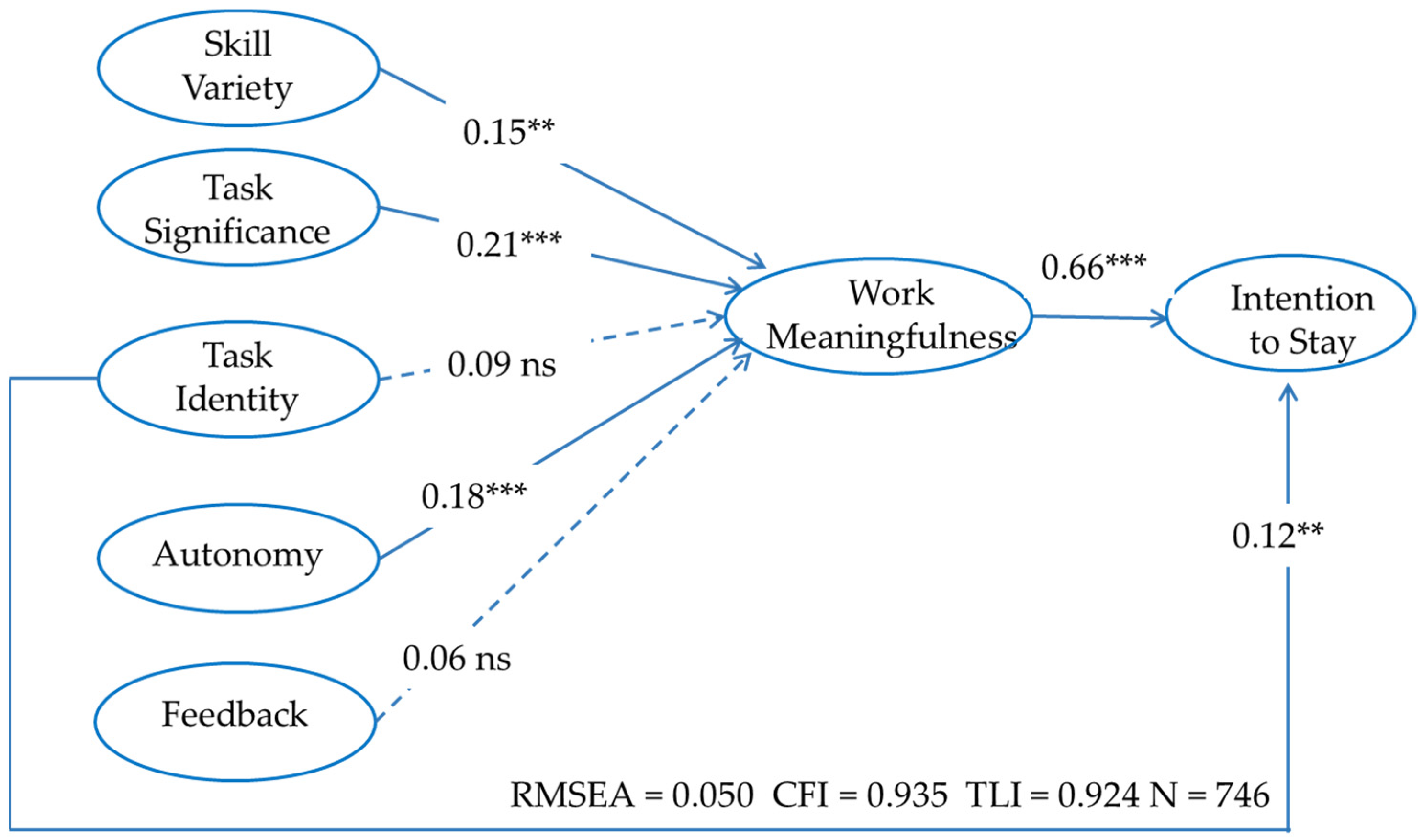

| Model | Model Description | χ2 | df | RMSEA | CFI | TLI | Model Comparison | ∆χ2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1: Full model (Partial mediation) | Five facets of job characteristics were specified to freely estimate both work meaningfulness and intention to stay. Work meaningfulness was specified to link with intention to stay. | 717.311 | 248 | 0.050 | 0.935 | 0.923 | - | - |

| Model 2: Constrained model | Based on Model 1, but the non-significant pathways of job characteristic variables (skill variety, task significance, autonomy, feedback) on intention to stay were constrained to zero. | 720.805 | 252 | 0.050 | 0.935 | 0.924 | Model 1 vs. Model 2 | 3.494 |

| Model 3: Constrained model | Based on Model 2, but the significant pathway of task identity with intention to stay was constrained to zero. | 727.485 | 253 | 0.050 | 0.935 | 0.923 | Model 2 vs. Model 3 | 6.68 ** |

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Work Meaningfulness | Intention to Stay | Work Meaningfulness | Intention to Stay | Work Meaningfulness | Intention to Stay | |

| Facets of job characteristics | ||||||

| Skill variety | 0.14 ** | 0.03 | 0.15 ** | 0.00 | 0.15 ** | 0.00 |

| Task significance | 0.21 ** | 0.06 | 0.21 *** | 0.00 | 0.21 *** | 0.00 |

| Task identity | 0.09 | 0.15 * | 0.09 | 0.12 ** | 0.10 | 0.00 |

| Autonomy | 0.19 *** | −0.09 | 0.18 *** | 0.00 | 0.18 *** | 0.00 |

| Feedback | 0.06 | −0.03 | 0.06 | 0.00 | 0.06 | 0.00 |

| Mediator | ||||||

| Work meaningfulness | 0.66 *** | 0.66 *** | 0.70 *** | |||

| Controls | ||||||

| Tenure | 0.17 | 0.05 | 0.17 | 0.05 | 0.17 | 0.06 * |

| Gender | −0.19 *** | 0.03 | −0.19 *** | 0.04 | −0.19 *** | 0.05 |

| Occupation | 0.15 ** | 0.04 | 0.15 ** | 0.04 | 0.14 ** | 0.03 |

| Indirect Effects a | 95% CI | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Estimate b | S.E. | Lower | Upper | |

| Facets of job characteristics | ||||

| Skill variety | 0.10 * | 0.04 | 0.03 | 0.16 |

| Task significance | 0.14 ** | 0.05 | 0.06 | 0.21 |

| Task identity | 0.06 | 0.16 | −0.01 | 0.13 |

| Autonomy | 0.12 ** | 0.04 | 0.05 | 0.18 |

| Feedback | 0.04 | 0.44 | −0.04 | 0.12 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Popaitoon, P. Fostering Work Meaningfulness for Sustainable Human Resources: A Study of Generation Z. Sustainability 2022, 14, 3626. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14063626

Popaitoon P. Fostering Work Meaningfulness for Sustainable Human Resources: A Study of Generation Z. Sustainability. 2022; 14(6):3626. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14063626

Chicago/Turabian StylePopaitoon, Patchara. 2022. "Fostering Work Meaningfulness for Sustainable Human Resources: A Study of Generation Z" Sustainability 14, no. 6: 3626. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14063626

APA StylePopaitoon, P. (2022). Fostering Work Meaningfulness for Sustainable Human Resources: A Study of Generation Z. Sustainability, 14(6), 3626. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14063626