Abstract

Education is of great importance in the context of climate change, as it can promote pro-environmental behaviour. However, climate change education is accompanied by didactic and pedagogical challenges because, among other reasons, climate change is a complex phenomenon and many people have a psychological distance to the topic. A promising approach to face these challenges is inquiry-based learning (IBL), as several studies show. To date, however, there are barely any empirically tested instructional designs, especially for close-to-science IBL, focusing on climate change. The study presented here therefore addresses the question of how a science propaedeutic seminar for upper secondary schools on the regional implications of climate change should be designed to ensure successful learning processes. Based on the design-based research approach, qualitative research methods (focus group discussions, semi-standardised written teacher surveys, and participant observations) were used to identify target-oriented design guidelines and implementation principles for such seminars. In the seminars, 769 students have so far researched different aspects of climate change in their own regions. The identified design guidelines and implementation principles were further operationalised for teaching practice, so that the research generated both a contribution to theory building and an applicable concept for schools.

1. Introduction

Climate change represents one of the greatest challenges for humanity in the 21st century. This situation not only requires economic and political measures but also the climate-literate behaviour of individuals and social groups. Thus, Climate Change Education (CCE), aiming for climate-literate people who are able and willing to face climate change via mitigation and adaptation, has been a central issue in the social and educational sciences in recent years. Whereas the complex mosaic of climate-related education and communication processes still needs further investigation (especially among young people; see [1]), related research so far was able to distil out not only the central challenges but also important criteria to pursue the intended goal of climate literacy. In the following, we will discuss the suitability of the Inquiry-Based Learning (IBL) approach to face key issues of CCE. We further show how IBL in the context of CCE can be brought to fruition at schools by applying particular design principles.

1.1. Climate Literacy

The overall goal in CCE can be described with the multidimensional construct of climate literacy [2,3]. According to Azevedo and Marques [3] (p. 422), “to be climate literate, one needs to:

- have some knowledge of climate science, in its content, procedural and epistemic components,

- master in some degree a number of competences that allow accessing and assessing relevant information about this theme, as well as communicate it in a meaningful way,

- reveal a set of attitudes that lead to one’s contribution to the conception and/or implementation of adaptation and mitigation strategies.”

As especially the first two aspects imply, climate literacy can be considered as a specific context of application for science literacy [2,3], which is defined by the competence to “explain phenomena scientifically [,] evaluate and design scientific enquiry [and] interpret data and evidence scientifically” [4] (p. 21).

While this concept of climate literacy explicitly considers the importance of climate-related attitudes, it also underlines the major role of science- and research-related competences. Therefore, learning processes in CCE should at best address both of them.

1.2. Important Challenges in Climate Change Education

However, these goals are not easy to achieve, as there are some major challenges in CCE: from both a factual and ethical perspective, climate change represents a complex issue [5]. Not only is the climate system itself technically complex [6], but so is the discourse about the topic, which is characterised by the interconnection of various aspects like ecological goals, economic interests, cultural orientations, social norms, and political decisions [7]. Consequently, learning processes should include opportunities to develop competences for dealing with complex topics. Given this complexity, it is also not surprising that international research in the field of conceptual change has shown that students often have incorrect, highly persistent conceptions of climate change—especially concerning the causes of climate change and potential solution approaches [8]. For example, many children and teenagers mistakenly confuse the ozone hole phenomenon with the anthropological greenhouse effect or assume that a confined greenhouse gas layer exists in the higher atmosphere [8,9,10,11]. On the whole, research shows that confrontation and active work with misconceptions in lessons is more effective than ignoring them [8,10]. This appears even more important against the background of the representation of climate change in the media or in political debates where we can find plenty of controversial information, and also “fake news”, particularly concerning the causes of climate change. Here especially, strategies to practice critical reflection of (sources of) information should be applied [12,13].

However, even if a more-or-less differentiated knowledge about climate change does exist—which is the case, for instance, in Central European societies [14]—a discrepancy between knowledge or awareness of climate change and personal attitudes or even action can often be observed [15,16]. This is especially true for young people [17]. Factors to elucidate this discrepancy are diverse: on a personal level, for instance knowledge, values and attitudes, interests and perceived self-efficacy play important roles, whereas situational factors like available infrastructure, economic circumstances, or social context also have considerable influence [14]. While this illustrates that knowledge alone does not inevitably lead to climate-literate behaviour, studies show that it is nevertheless an essential precondition for it [18].

Aside from other factors, one explanation for the described knowledge–action gap is that climate change is often perceived as a rather abstract phenomenon, especially in Western countries [19]. Many individuals think that their opportunities for action are very limited and that they cannot make a difference. This can at least be partly explained by so-called psychological distancing: while many people do accept the fact that climate change is happening, they often ascribe it to other parts of the world and a distant future [14]. Especially adolescents tend to consider climate change irrelevant to their immediate everyday realities [20]. Consequently, creating psychological proximity is not only deemed to be a potential factor for awareness of and concern about climate change [19,21,22,23], but also a strong relevance to one’s everyday life in general supports the communication of climate issues among adolescents [14,24].

1.3. Inquiry-Based Learning as a Promising Approach for Climate Change Education

Overall, the challenges described above ask for adequate educational measures to counteract them. While there is still research to be done, studies were already able to outline a set of key principles for environmental and climate change education. For instance, in a systematic literature review, Monroe et al. [25] (p. 791) identified the following: both “(1) focusing on personally relevant and meaningful information and (2) using active and engaging teaching methods” are most common in environmental education, while particularly for CCE, “(1) engaging in deliberative discussions, (2) interacting with scientists, (3) addressing misconceptions, and (4) implementing school or community projects” were identified as the central principles to foster climate literacy. Consequently, educational conceptions should at best encompass all of them to be potentially fruitful.

One promising approach to adapt these principles is Inquiry-Based Learning (IBL). This term refers to educational work-forms, which serve the search for and finding of knowledge that is new (at least) to the learner, and which happen analogous to the characteristics of scientific knowledge production regarding attitude, methods, and systematic proceeding [26,27,28].

Corresponding work-forms bring along the potential to realise exactly Monroe et al.’s [25] above-mentioned four principles for CCE because IBL can be implemented in comprehensive school projects. There, reflection and classroom discussions can be complemented by interaction with scientists and through students’ intense scientific activities on individual research questions, they can be confronted with their own misconceptions.

Indeed, research shows that IBL is capable of addressing competences that are considered central components of scientific literacy and/or such that contribute to overcome the aforementioned challenges in CCE:

According to different authors [29,30,31], IBL can help to develop an array of so-called 21st century skills (e.g., creativity, innovativeness, collaboration and communication, critical thinking, problem-solving, or decision-making) in general. In addition, relevant empirical research shows a broad spectrum of encouraging insights with regard to specific goal dimensions of climate literacy. For instance, various studies were able to point out positive effects of IBL on critical-thinking skills (e.g., [31,32,33,34]). Duran and Dökme [35] could prove a better support of critical thinking via IBL in comparison with conventional approaches. Such skills are especially useful with regard to the formerly described media and political discourse about climate change as they help, for example, to uncover simple truths.

In relevant studies, IBL was able to foster conceptual change in general [36] and to improve students’ perception of the greenhouse effect in particular [37].

Several studies observed increased motivation of learners via IBL (e.g., [38,39]), whereas some of them even found positive effects on the feeling of self-efficacy [40,41]. These findings are of particular importance, as feelings of powerlessness and hopelessness towards climate change represent a great challenge in CCE [14,42,43]. In contrast to that, motivation and self-efficacy represent crucial prerequisites for sustainable action [44,45,46].

Actively experiencing research by learners may promote a better understanding of scientific concepts [47,48], which Klein [49], Mao et al. [50], and Chang and Mao [51] have particularly shown among the Earth sciences. More specifically, Namdar [52] conceived IBL on the subject of global climate change for future teachers, who thereby could significantly enhance their understanding of global climate change. Additionally, IBL can increase scientific process skills [53]. Arieska Putri et al. [54] could even show a direct effect of IBL on scientific literacy.

This is not very surprising in that science literacy (and, more context-specifically, also the initially described climate literacy) is very strongly related to the desired key competences, which are usually addressed especially by close-to-science IBL formats (for a detailed distinction of different IBL formats see for example [55]); Gess et al. [56] (p. 79) describe the intended “research competence” as a combination of receptive research skills (i.e., information literacy, statistical literacy, and critical thinking) and productive research skills, which include cognitive competences (e.g., knowledge about research processes and methods, generation of hypotheses, or data analysis), affective-motivational competences (e.g., research-related self-efficacy or tolerance of uncertainty and ambiguity), and the social competence of cooperation in a learning community. According to them, involvement in IBL should additionally foster a so-called research attitude, which comprises a reflexive distance, epistemic curiosity—i.e., an intrinsically motivated tendency to gain new insights [57]—and differentiated epistemological beliefs, in the sense of personal assumptions about the nature of knowledge and the process of knowledge creation [58].

Wiemer [59] argues that the achievement of such competences is facilitated by some particular learning and reflection processes in IBL, such as dealing with uncertain knowledge and undetermined results, experiencing and communicating basic scientific values and attitudes in a scientific community, or the transition from an everyday perspective to a scientific perspective and development of an own reasonable and justifiable position.

In order to operationalise IBL in such strongly science-oriented forms, IBL conceptions should be characterised by a set of design guidelines described in literature:

- An extensive timeframe, in which a whole research cycle can be realised [60,61,62,63,64],

- Learning processes that build on research questions that are not pre-determined by the teacher but self-determined by the students’ based on their individual interests [26,61,65,66],

- Complex content that can be addressed from different scientific perspectives [26,67],

- Extensive application of methods commonly used within a scientific discipline [68], at best with the opportunity to choose from a broad methodical repertoire [67],

- Aiming at research findings that go beyond the individual learning processes and might be of common (scientific) interest [69],

- Critical reflection and transparent, comprehensible communication of research results and methods [26,60,65,70],

- High amounts of self-directedness and self-responsibility over the whole research process [26,62,71,72,73],

- Various opportunities to experience research as a social, cooperative process [26,48,74],

- Organisational and content-related openness [26,67],

- Authentic problems that allow the embedding of learning processes into the complex context of everyday realities [26].

Given this empirical and theoretical background, because of its inherent characteristics IBL appears to be a suitable approach for fostering climate literacy, if extensive science-oriented formats are applied.

1.4. Implementation of Inquiry-Based Learning at Schools

Unfortunately, it is precisely these close-to-science formats that are most rarely applied in school contexts (one exception is the “FLidO” project, which is currently under development—see [75,76]). This can be partly explained by the fact that IBL, at least in Germany, has a longer tradition as a university-didactic approach and therefore the scientific discourse is still predominantly located in this context (see for example [26,74,77,78,79,80,81,82,83,84]). Besides that, literature describes various challenges in IBL (see for instance [65,85,86,87,88]), which doubtlessly represent even more limiting factors regarding school education. Our own practical experiences at schools, as well as the considerable feedback from teachers, show that one of the greatest hindrances is the rigid and narrow timeframe provided by school curricula, which usually allow neither the accomplishment of a whole authentic research cycle nor activities like field research that deviate extensively from the usual “portioned” lesson structure. Moreover, strongly science-oriented IBL comes along with increased content-related, methodical, and intellectual complexity and difficulty, which represents unaccustomed challenges not only for students but also for teachers. Teacher education tends to have a limited research orientation. Against this background, many teachers have little experience in conducting and supervising research projects. Many teachers are uncertain about the collection and analysis of data, and also about subject-specific concepts, theoretical backgrounds, and the nature of science, as well as research ethics.

As a result, especially in geography education, IBL often focuses on experimental work-forms (see for example [89,90,91,92,93,94]), as such approaches might usually be not too time-consuming and because the clear structure is better controllable and manageable. Correspondingly, insights on effects and preconditions of IBL are predominantly derived from concepts within the domain of natural science education, while those from the humanities or social sciences are rather seldom (see for example [68,95]).

Many school projects and other forms of open education give students and teachers the freedom to determine for themselves the topics to be covered. This is a great advantage especially when, for example, climate change is not included in the existing curricula. The so-called W-Seminar at Bavarian high schools (Gymnasien) provides an especially suitable framework for such project-oriented teaching. It represents a science-propaedeutic seminar (“W” abbreviates “wissenschaftspropädeutisch”, which translates as “science propadeutic”) format in senior classes (grades 11 and 12, students aged 15–18), on the threshold between school and university. Within the period of 1.5 years, students are meant to conduct research on an individual topic and write a scientific seminar paper about it. Combined with IBL, this format provides the potential for students to learn “in their own backyards” and to create psychological proximity, to link different spatial and temporal scale levels, and to foster conceptual change. Unfortunately, while there are official guidelines for planning and exerting a W-Seminar [96,97,98,99,100], targeted considerations about how to implement close-to-science IBL in this framework do not exist at all. So, approaches in the particular context of CCE cannot be built on existing templates. Consequently, we aim to fill this gap with our research.

1.5. Purpose of the Study and Research Questions

As shown above, IBL brings potentials for CCE when conceived in close-to-science formats. Nevertheless, the realisation of authentic, science-oriented propaedeutics according to the IBL approach in school contexts is a big challenge and, therefore, concrete conceptions are rare. At the same time, (domain-specific) didactic theory is still lacking specific knowledge on the school-based application of IBL in general and its application particularly in CCE contexts. Especially for the school context, transferable how-to guidelines for close-to-science IBL are barely available (for the university context see [64,81]). Therefore, our research aims at the identification of design principles for the realisation of close-to-science IBL environments in the context of climate change at upper secondary schools to address the potentials and challenges outlined in Chapter 1. Hence, our research question is:

RQ1: How should a science propaedeutic seminar on regional implications of climate change be conceptualised in upper secondary schools to support successful learning processes in a close-to-science IBL approach?

To create a context-specific theoretical framework for the desired learning environment, research sub-question 1a is:

RQ1a: Which design guidelines and implementation principles can be identified for the [successful] design of close-to-science IBL on regional implications of climate change in upper secondary schools?

To apply this theoretical framework for the design of a concrete learning environment as a practical research output, research sub-question 1b is:

RQ1b: How can the identified principles be operationalised for the target group of upper secondary school students in the conception of a learning environment?

2. Methods

2.1. Methodological Framework: Design-Based Research

These research questions focus on a so-called theory-practice problem [101]. Therefore, we address these issues by implementing design-based research (DBR) as a methodological framework. As an application-oriented basic research approach, DBR is particularly appropriate for such theory-practice problems [101,102,103,104] because it combines empirical educational research and theory building with the development of learning environments in practical contexts [103,105,106].

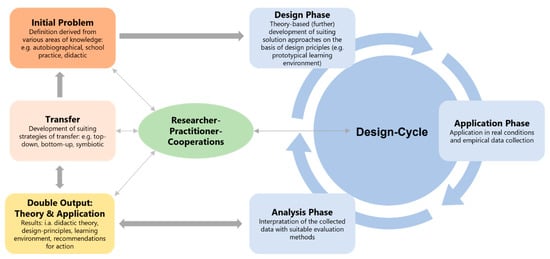

We follow a typical DBR research structure that consists of characteristic core elements (see Figure 1). Starting from the underlying problem, an initial design of the learning environment must be developed. As typical in DBR, this was based on a researcher-practitioner cooperation: together with a teacher, we developed a concept for a W-Seminar on the regional implications of climate change. For this purpose, we developed design principles that are central to the DBR processes. These are considered to be context-specific design criteria on different levels of concretisation (for a detailed definition see [104]).

Figure 1.

Schematic structure of a DBR research process (adapted and translated from [104]).

In a first step, we derived a set of superordinate “design guidelines” from theoretical and empirical research literature to comprehensively implement science-oriented IBL and bring its potentials regarding CCE to fruition (see Chapter 1). These theory-based design guidelines were set as a baseline for the subsequent research process and therefore not subjected to further modification. Based on them, we developed a structure for the seminar concept by applying the logic of a prototypical scientific research cycle to the organisational framework of the W-Seminar format. In a second step, for the individual phases of the conception we derived further design principles on the specific levels of operationalisation from the superordinate design guidelines; in doing so, design guidelines were differentiated into “implementation principles” (i.e., influencing factors at key points that are likely to be relevant in the design of the learning environment). These in turn were translated into a “target-group-specific operationalisation”, which consists of a finely structured set of individual didactic-methodical decisions. As a concrete practice output, these three levels of design principles can then be realised as detailed tasks, methods, materials, and the like. Table 1 represents an exemplary illustration of the systematic approach in the DBR process, as described above.

Table 1.

Examples for the different operationalisation levels of design principles.

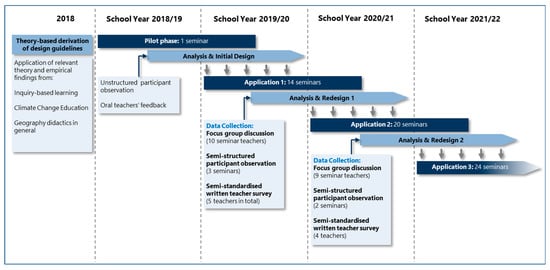

In a third conceptual step of the initial design, we created a pilot version of the learning environment based on this catalogue of theory-driven design principles, applied it in the pilot W-Seminar and evaluated it via unstructured participant observation and oral teacher feedback (see Figure 2). Therefore, researchers intensively accompanied the individual sessions of the entire seminar (except a few single sessions that were spent on classroom tests or organisational issues) to detect any aspects that appeared relevant. In addition, our cooperating teacher gave us regular feedback on her observations over the whole seminar process. These practical experiences allowed us to identify the first central requirements for lesson practice and to integrate them into the initial design.

Figure 2.

Concretised structure of the DBR process (own representation).

Finally, we subjected the completed initial design to two main design cycles. In total, 34 teachers and 433 students participated in the 34 seminars that were included in these two main cycles (14 seminars in cycle 1 and 20 seminars in cycle 2). In total, together with cycle 3, 769 students were part of the seminar. Teachers (mainly in the public school system) could voluntarily apply with their classes for the seminar concept, which was promoted via the central institution for teacher training and professionalisation in Bavaria. The offer should address every interested teacher–in doing so, we were able to include teachers with diverse backgrounds, such as different experiences in science teaching and CCE, different subject combinations (in Germany, teachers at secondary schools usually teach two or more core subjects), or different overall teaching experiences. This enabled us to assess multiple needs during the DBR process and to address them with our conception. The fundament of the application in these two main cycles was a comprehensive in-detail teachers’ manual, including lesson schedules, planning documents, templates, learning materials, theoretical backgrounds, and additional information sources, which was handed out to the teachers in the respective latest version (a current version is available as a preprint; see [107]). To make sure the conception would be exerted in the intended way, we developed a three-day teacher training session, in which our cooperating teachers participated in advance of the respective W-Seminar. Additionally, participating teachers were given the opportunity to contact us via a weekly telephone consultation hour. This showed that teachers, in sum, were getting along very well with the manual and the basics conveyed in the teacher training—questions mainly focused on organisational issues like lending research equipment from the university. In all schools, the same teacher was teaching the same students over the whole course of a seminar.

The seminars of each generation started at the beginning of a new school year in September. As the total duration of a W-Seminar is 1.5 years, this created an overlap of half a year in the pilot phase and the two main research cycles. Consequently, the data analysis and redesign had to be timed to gain a head start for the implementation of the results into the next cycle. This means that while the respective new seminar generation had already started based on the redesigned conception of the first seminar phases, data analysis for the redesign of the advanced seminar phases was still carried out (see Figure 2). The insights gathered from the main cycles 1 and 2 were finally implemented in “Application 3”, which is currently being carried out at 24 schools (24 teachers and 336 students) but not subjected to the above-mentioned research questions.

The goal of this DBR-typical iterative approach was to investigate the suitability of the identified design principles for supporting different facets of students’ learning processes during IBL. In doing so, both design principles and the resulting learning environment could be optimised and further developed successively through the iterations of the DBR process.

2.2. Data Collection and Analysis

With our research, we aimed to consider as many aspects and influencing factors regarding successful learning processes as possible. This open, explorative character requires a holistic in-detail assessment of the learning processes in a natural application context rather than controlled conditions [108,109,110]. Therefore, we chose to employ methods from the qualitative paradigm.

As we wanted to include both the teachers’ perspective and the researchers’ perspective into the assessment of our research questions, we applied data- and method-related triangulation [110,111] by employing the following methods.

2.2.1. Focus Group Discussions

As one approach, we referred to the experiences and observations of cooperating teachers who applied our seminar concept during the respective main design cycles. For this purpose, we applied focus group discussions, in which the group members discuss a selected topic and mutually react to their considerations with, for example, consent, denial, or complementing remarks [109,110,112]. This was particularly necessary to draw as precisely as possible an image of the important aspects for the assessment of our research question. To structure and focus the discussion, we concentrated on the following perspectives:

- Evaluation of the overall process structure,

- Selected aspects of specific seminar phases (e.g., comprehensibility of particular learning materials),

- Evaluation of student interest and motivation over the course of the learning process and assumptions about influencing factors,

- Evaluation of the practical suitability of different seminar units and learning tasks,

- Experiences with implemented guidance measures,

- Experiences and challenges regarding the specific teacher role.

In design cycle 1, we had 10 cooperating teachers participating in the discussion, and 9 teachers in design cycle 2. The focus group discussions were recorded on video and transcribed for further processing.

2.2.2. Semi-Standardised Written Teacher Survey

Additionally, we employed semi-standardized questionnaires [109,113,114]. In advance of the focus group discussions in research cycle 1, teachers were asked to share their experiences with the seminar conception regarding a set of selected questions. Five teachers answered the questions, which were, for example:

- “In your opinion, what went well in your W-seminar in phase XY, and what did not?”

- “In what way do you consider the structure of phase XY-regarding the internal structure of the individual lessons and the sequence of sessions within the phase-to be effective, and in what way not?”

- “At which points do you consider the guidance measures for students provided in the concept as appropriate, and at which points not (e.g., work materials, learning tasks, didactic-methodical decisions, teaching impulses)?”

- “How do you determine your assessment and what suggestions can you think of to make the guidance even more effective?”

For a more detailed assessment of single seminar lessons, especially within the emergence and planning phase, teachers were asked to answer questions on specific aspects of their impressions and observations during the learning processes after each lesson. These questionnaires were answered by four teachers each in the first and second design cycles. Exemplary items from the questionnaire are:

- “At which points of this session could the intended competence goals be achieved?”

- “How would you estimate the motivation of your students during this session and by what was it influenced from your point of view?”

- “At which points did you as a teacher get along well with the conception of this session, and where less so? What are possible reasons for that?”

- “In your opinion, how clear was the aim of the session’s individual learning steps to your students?”

2.2.3. Participant Observation

We complemented the teachers’ perspective by semi-structured participant observation [108,109,110,114]. During various lessons throughout the seminar application, a researcher was present in the classroom and followed the events. The lessons to be observed were chosen based on the insights of the pilot cycle. We included seminar sessions that were most likely to represent challenging steps of the IBL process, and therefore were most likely to provide promising insights in the observation (this applies, for example, to the classroom sessions of phase B, all the lessons of phase C, or the fixed-point sessions of phase D—see Table 3). The researcher’s observations were based on a semi-structured observation sheet, which focused on the assessment of existing design principles but also allowed unexpected observations. Perspectives of the observation sheet were, for example, observable outcomes of individual learning tasks, indications of students’ comprehension problems, visible influences of activities on students’ motivation, interaction between teacher and students, or the suitability of the structure of learning steps. During the observations, the researcher only interacted with students on a few occasions (e.g., small talk when observing students working in groups, or organisational issues like how to use university infrastructure, such as online public access library catalogues). This procedure was applied to three selected seminars in the first main cycle and two seminars in the second main cycle. The observation sheets were digitalised for further processing.

2.2.4. Data Analysis

The data gathered through all of the above-mentioned methodical approaches were finally analysed via qualitative content analysis. More specifically, we applied a combination of thematic and evaluative qualitative content analysis [115]. In a first step, the existing design principles were applied to the data as deductive analysis categories to identify those of the design principles that seemed to be most relevant during the learning processes (e.g., by appearing very frequently or particularly emphasized in the data). Additionally, inductive categories were generated from the material (i.e., scattered observations that are thematically related and can therefore be summarized in a new category). In a second step, the design principles (respectively their target-group-specific operationalisations) that could be identified as relevant by this means were evaluated to find out if they exerted a positive or negative influence on the learning processes. From the results of these analyses, we drew conclusions about the initially derived design principles (respectively their operationalised implementations) that have an observable impact on the learning processes, and about the way in which they foster the intended learning outcome. Based on these insights, we refined and complemented the set of design principles and applied them for the redesign of the learning environment as a starting point for the subsequent research cycle.

3. Results

Based on the initial literature research, we were able to identify a set of superordinate design guidelines for close-to-science IBL at schools. As mentioned above, they were applied as a baseline for the subsequent research process. We differentiated this set of design guidelines down on all levels of operationalisation (see Table 1) as a basis for the concrete design of our learning environment. Over the course of the pilot phase and the two main research cycles, we reworked and adjusted the catalogue of underlying design principles. An overview of the final design guidelines and implementation principles is given in Table 2.

Table 2.

Theory-based design guidelines and derived implementation principles for Inquiry-Based Learning in the context of Climate Change Education.

Based on them, we created and successively redesigned the learning environment, which incorporates finely structured didactic-methodical decisions on the level of target-group-specific operationalisation, as well as concrete tasks, methods, and materials. A summary overview of the final structure of the learning environment is given in Table 3: The first column shows the chronological structure of the seminar phases and individual sessions. The second column provides short descriptions of the sessions’ central contents, which at the same time represent the target-group-specific operationalisation (see Table 1) of the implementation principles that come to fruition in the respective seminar sessions. The underlying implementation principles, in turn, are depicted in the right column of the table. For example, the design guideline 2b (“IBL should include learning steps that enable students to formulate individual research questions based on their interests.”) is realised via the provision of central quality criteria for adequate research questions in session C4 of the seminar concept.

Table 3.

Final operationalisation structure of the learning environment and underlying implementation principles.

To demonstrate how these results were achieved, we exemplarily elucidate selected findings in the following. All the aforementioned research methods delivered important and useful data. Especially, the teachers’ quotes obtained from the focus group discussions and the teacher surveys were most suitable to present vivid insights into the data. In the following, we therefore integrate exemplary quotes to illustrate our research findings.

On the whole, one overarching insight emerged from the data: in IBL, many factors—such as the composition and prerequisites of the learner group—come together to create learning processes that are often difficult to plan and that need to be guided and supported depending on the situation. This requires advanced competences from the teachers, such as for example procedural/methodical skills, factual knowledge, or the ability to provide ad hoc support in various learning situations. Consequently, many teachers expressed great uncertainty regarding their capability to adequately deal with all these eventualities, as, for example (all quotes presented in this paper are translations of the original German-language source material):

“[…] I have a [research question by a student] about climate-sceptical media and their influence on people. [...] For me this is rather difficult now, this whole media thing, as I am a natural scientist.”

“The topic of research methods and their implementation is a challenge for many students which they do not really dare to approach, because such work is completely unknown to them, and they would like more preparation. Because of all the different [approaches], this is of course not easy [for me].”

“Beginning with session C2 […], the teacher should also be clearly aware that all of the following work steps lead to the students’ moving on to their research questions […]. The challenge is that you calm down the students who panic quickly and assure them that they do not have to worry about choosing the wrong topic or about not finding a suitable research question.”

These insights clearly express the need to design the learning environment in a way that not only supports the students in their learning processes but also the teachers in guiding these learning processes. Therefore, this finding has not only led to the inductive development of respective design principles (see Table 2, principles 16a-16f), but has also strongly shaped the target-group-specific operationalisation of all the other design principles in the learning environment. In sum, we addressed these challenges in two ways: on the one hand, we optimized the teachers’ manual by integrating numerous remarks, tips, suggestions, additional information and materials, and other supporting elements for the teachers (e.g., hints to provide learning impulses in particular lesson phases and brief heuristics on how these impulses could be given), and on the other hand, we modified the students’ learning materials, tasks, and information sources so that they simultaneously aid the teachers to support students’ learning processes.

This was the case, for instance, in phase B, which was designed particularly to enable students to acquire important knowledge about climate change on both a global and regional scale, which includes the differentiation of existing mental representations (conceptual change). To help teachers convey this complex, extensive knowledge (see implementation principle 16a), we developed a set of interactive online learning modules that focus on the causes and functionality of climate change, its global and regional effects, and the factors that influence the individual and societal perceptions of the phenomenon. To realise important design guidelines, such as 12 (“IBL should support students to intensively immerse into and research the factual basics of the respective context.”) or 13 (“IBL should draw on targeted insights into authentic science.”), these modules were designed to be very target oriented from the very beginning, for instance by including reflections on the nature of climate science and the validity of its findings. To present the modules’ contents in a vivid, comprehensible way, they were designed in a multimedia format (text, tables, graphics, videos, audios, and interactive tasks). Additionally, they contain various self-examination and summary tasks to self-check the individual learning progress. Nevertheless, the evaluation of the pilot phase already showed that both motivation and learning success decreased over time when students only worked self-directedly via the online modules. As a consequence, following additional design principles like 8b (“IBL should include various occasions for common and mutual reflection.”), we implemented fixed-point sessions in between the homework phases to discuss the content of the respective modules and to consolidate the desired knowledge in plenary. With this rearrangement, motivation and learning success during phase B could be significantly increased. Over the course of the main research cycles, the structure of these fixed-point sessions could be further improved: the final version of session B2, for example, was focused more strongly on supporting conceptual change (implementation principles 11a, 11b, and 11c) by implementing a classroom quiz and a role play in which students are asked to discuss causes and functionality of climate change from the perspectives of scientific common sense vs. climate scepticism. The contents of the redesigned version of session B4 were oriented closer to students’ everyday realities (e.g., implementation principles 6b and 10c), as they are required to reflect the influenceability of own perceptions, for instance by media “framing” and “agenda setting”. The newly designed learning materials for these sessions at the same time represent an orientation for the teachers to support the consolidation of factual knowledge and to moderate reflection processes (implementation principles 16a and 16e). As focus-group discussions showed, the overall final structure of phase B met the desired goals:

“So that’s really great, the whole concept with the online course laboratory, all of the basic modules and specialisation modules that are stored there. The students loved it, really. So, they really enjoyed working with the whole thing. [...] I then wrote an impromptu task about it. [...] It turned out quite neatly too. [They] learned quite well.”

As a second main goal of phase B, which forms the basis for the emergence and planning phase, students should already be given the opportunity to focus on individual interests within the context of climate change (implementation principle 2a: “IBL should provide occasions that allow students to find individual fields of interest for their research projects”). For this purpose, we created different specialisation modules, which address regional implications of climate change from different thematic perspectives. They focus, for example, on interactions between climate change and forest ecosystems, effects of climate change on pollen allergies, or implications of climate change for urban areas.

In the pilot version of our seminar concept, every student was meant to work with every one of the specialisation modules and then choose their individual field of interest. As insights from the pilot phase indicated that students should be able to focus on individual interests earlier in the learning process, this part of phase B also underwent a redesign by applying additional design principles (such as 7f: “In IBL, students should be enabled to self-direct their acquisition of basic knowledge about the given thematic context to an adequate extent”). Students can now choose two out of seven of the specialisation modules to further engage with. That this indeed allows them to set a rough direction for their further planning is shown, for instance, by the following quote:

“And what was very good in finding the research question were the specialisation modules. [...] I also had them give presentations there. After that, most of them already knew in which direction their research should go. Then they also developed their own ideas and then brought in a lot of personal things.”

The extensive field research period in phase D obviously enables the most self-directed and self-responsible activities of the students’ individual research projects. While this comes along with extraordinary high degrees of autonomy, it also carries the risk for students to feel left alone or get bogged down in their research. Therefore, as our research has shown, an adequate amount of individual guidance is necessary in this phase, especially during the first weeks of field research. To pursue this goal, the idea of employing targeted fixed-point sessions, as described in the table (see Table 3, phase D), has proven to be suitable in general. At the same time, the individual counselling for students by the teacher turned out to be especially difficult and time-consuming:

“Advising students is sometimes difficult, but necessary. [...] More time would be needed for the deliberations.”

Therefore, we redesigned session D2 via two major adjustments. On the one hand, we detached individual counselling from the idea of a single plenary session and instead recommended to spread the counselling sessions over several days. Additionally, teachers should request written progress descriptions by their students in advance. On the other hand, we formulated hints and key questions in the teachers’ manual as a guideline for them to facilitate target-oriented advisory (which refers to design principles 16b, 16c, and 16d). Focus-group discussions showed that these adaptations led to significant improvements:

“The one-on-one meetings that have already been held have worked very well. The students sent me information on the current status of their research by E-mail. This was extremely helpful for the individual advice.”

In general, design guideline 5 (“IBL conceptions should provide an adequate amount of guidance for the students.”) has proven to play a major role. While each of the seminar phases is characterized by particular difficulties that require suitable guidance measures (e.g., the previously described self-directedness of phase D), one vivid example of this is the balance between teacher-guidance and peer-feedback, which plays an important role in several seminar sessions: Following design guideline 8 (“IBL conceptions should create various opportunities to experience research as a social, cooperative process.”), we implemented various occasions for students to mutually reflect on their progress and support each other by differentiated feedback (i.e., implementation principle 8b and 8c). Our data show that in many learning steps these peer activities were successful:

“The peer review was very motivating, as the students asked their classmates questions and felt that they were being taken seriously. During this phase, the students were particularly focused. [...] Competence goal 1 [= ‘Students give their classmates constructive feedback on their Mind Maps.’] could be fully achieved in the peer review phase [...].”

“This phase [= phase C] worked very well, as the students quickly discovered critical points through the communicative exchange that they would hardly have come across on their own.”

But on the other hand, we also found much evidence for situations in which such peer activities were not sufficient, but the respective tasks required stronger feedback and guidance by the teachers:

“So there, [with] just this peer feedback, they were a bit unsure [...] whether [...] their research questions, their ideas, whether they can be implemented, whether this is something applicable. [...] At some point they said that it didn’t help them either, because they wanted to know what I was saying about it.”

“I mean, […] you shouldn’t really be surprised if the whole school experience has so far resulted in the fact that the teacher clarifies what is right / important, how the course is to be set–of course it is clear that this expectation is there, too. In addition to the peer feedback, it is probably really important that the teacher gives this security.”

Fortunately, there are also several components in the learning environment, for which the set of underlying design principles worked out quite well from the beginning and which therefore underwent no further adaptations. So, for example, research data on session A2 show almost entirely indications of successful learning processes. This session was designed to get students in touch with genuine research, as well as the climate change phenomenon, within their everyday realities. Here, the implementation principles 4b, 8a, 8b, 9a, 10a, 10b, 13a, 13b, 14c, 15b and 16b played especially major roles. These were operationalised with a brief excursion in the students’ home region, based on the “jigsaw” method. There, students are given the possibility to apply methods commonly used within a scientific discipline to exemplarily inquire into selected implications of climate change in their immediate surroundings and to share and reflect on their experiences in groups. Focus-group discussions showed that teachers perceived these activities as very successful (e.g., regarding the scientific connection between global climate processes and locally visible aspects) and observed intense and motivated learning processes among their students, as exemplarily illustrated in the following quotes:

“Especially the entry into the seminar, where there was also a strong presence at school, was very successful, phase A. [A]nd then also with the […] jigsaw-method, the students were very happy to do that.”

“[The] introduction to research methods was intensively conveyed especially via the excursion and was kept in remembrance by the students.”

4. Discussion

In this paper, we investigated how a science propaedeutic seminar on regional implications of climate change should be conceptualized in upper secondary schools to support successful learning processes in a close-to-science IBL approach. Therefore, we identified a set of influencing factors, which play an important role for the success of such approaches, particularly in the school context. Correspondingly to these factors, we derived and differentiated a catalogue of central design principles, as depicted in Chapter 3, on three different levels of operationalisation. Referring to RQ1a, especially the identified design guidelines and implementation principles represent insights on a theoretical level, which we consider as transferable to a certain extent. Applying them allows us to realise close-to-science IBL in upper secondary schools and similar educational contexts. As these principles provide a design framework, which was so far missing outside of the higher education context, they can form the basis for targeted science-propaedeutics at schools addressed to the acquisition of science literacy and other science-related competences (see [6,56]). Referring to RQ1b, we provide design principles on the most concrete level of target-group-specific operationalisation that simultaneously represent detailed context-specific how-to-guidelines for designing close-to-science IBL environments on the topic of climate change. As shown in chapter 1, such learning conceptions can support the achievement of climate literacy via the described characteristics and hitherto observed effects of IBL. Moreover, the final learning environment as a whole, which was created throughout the DBR-process, represents a valuable output on a practical level, as it is available for practitioners in an applicable, ready-to-use format.

Our findings stand in line with previous research on requirements and principles of good practice CCE: For instance, Cross and Congreve [116] identified seven principles for good climate change teaching in the context of undergraduate higher education which match our set of design principles in large parts. Their postulates, such as that in CCE assessment needs to be authentic, that students’ skills to engage with climate change (as a wicked problem) should be clearly scaffolded, or that climate change teaching should be meaningfully enriched by appropriate technology can be confirmed by our design principles, respectively the experiences with our learning environment.

Nonetheless, the study is explicitly focused on close-to-science IBL. Against this background, the generated design principles and the resulting teaching concept can certainly only unfold their full effect in didactic arrangements that offer the framework conditions for close-to-science IBL. These temporal and organisational framework conditions are especially given in project-oriented teaching. The example of the science propaedeutic seminars in upper secondary schools in Bavaria shows what is possible at schools—if enough time is made available for inquiry-based learning. It is a great pleasure to experience the students’ motivation and sense of achievement that can arise in such a learning arrangement. Unfortunately, however, such frameworks do not exist often, both in Germany and in an international perspective, and it is often not easy to create them given the complexity of educational systems. Often, individual schools can make few independent decisions because they are dependent on the educational policies of their district or state. We believe that IBL has such a high educational value that a course should be set in educational policy to provide such learning experiences to as many students as possible.

As one of the most central findings of this study, we consider the fact that the teachers in close-to-science IBL at schools represent an important influencing factor on the success of the learning processes, which is consistent with Hattie’s findings [117,118] and in the context of climate change with implications made in a study by Onuoha et al. [119].

In line with this, our data shows comparatively high demand on teachers in IBL in many dimensions of professional teacher competence (see [120,121]). This is particularly true for the dimensions of Content Knowledge (CK) and Pedagogical Content Knowledge (PCK), because here these are not limited to the respective school subject (here geography). Rather, CK and PCK on a factual and procedural level extend to the whole scientific dimension of the subject, which goes well beyond what is usually required from teachers in a school context. One potential attempt to address these challenges could consist in a more widespread integration of IBL into university-based teacher education, as for example Huber [26] or Fichten [79] demand. Inquiry-based learning in teacher education can not only be exciting and motivating, but also generate experiences from which students can later benefit. Teachers who have collected and analysed data themselves in their training and, in the best case, have also had the opportunity to reflect on the nature of science, can bring these competencies to bear in their work with their students.

Additionally, IBL requires advanced skills on the level of teacher noticing (see [122]), especially the many situations over the course of IBL processes, in which ad hoc support by the teacher becomes potentially necessary, that require both an advanced perception of students‘ need of guidance and an adequate reaction to it.

Beyond the dimension of professional skills and knowledge, we learned from teachers‘ feedback that they also felt uncomfortable with the different teacher role. In close-to-science IBL, teachers are not meant to be omniscient educators and conductors of the learning processes, but rather coaches and learning companions on eye-level with the students [64,85] and, as such, part of a research (and learning) collective. Against this background, a shift from still widely present transmissive views on learning to a more constructivist perspective seems necessary. Especially in the IBL context, approaches like Knowledge Building could be promising [123,124,125].

In sum, with its findings this study builds the foundation for further research. So, for example, a quantitative approach with standardised instruments seems very promising to assess the acquisition of intended science- and climate-related competences by students learning with the designed IBL environment. Additionally, effects of the conceptions on important CCE-related constructs could be measured in further studies, so for instance the reduction of psychological distance, the fostering of Conceptual Change, increases in critical thinking skills, or effects on students’ interest and motivation.

Limitations

Nevertheless, there are still some important aspects to shed light on. First, detailed insights particularly on the emergence and planning phase (= phase C in our conception) are missing so far. This is important in that a closer look, for example at official planning documents for school practice (e.g., [100]), shows that it is usually exactly this phase of the research cycle that is left out or at least vastly narrowed down. Given the fact, that this phase is explicitly considered as an important element of IBL [60,61,63], insights on the underlying difficulties and challenges are needed. Consequently, throughout our DBR project we have been collecting additional data on phase C, which is currently being analysed. Furthermore, our observations do show that our IBL environment can support dispositions for climate-related action among the students, but targeted educational elements to specifically foster climate-related action, respectively dispositions for action, are not yet implemented within the conception. Approaches to address this dimension are the subject of a current research project.

Additionally, research findings on the regional and individual approach, which is central to our IBL conception, are currently missing. The idea of students conducting research in their immediate surroundings, within their own everyday realities, and based on their individual interests represents a core element of our learning environment. Due to research literature, these characteristics are very likely to result in effects that are desirable in the CCE context (e.g., the reduction of psychological distance to the climate change phenomenon, or the fostering of conceptual change by own experiences). In our study, we have taken these theoretical linkages as basic presumptions on which we developed our conception. Nevertheless, it seems very promising to examine how far our IBL environment contributes to these effects. Here, targeted approaches might help to gain interesting insights. This also applies for the perspectives of the students. These were so far only assessed indirectly via the teachers’ observations. Thus, it has not yet been finally clarified how the learning environment affects motivation, interests, and willingness to engage in pro-environmental behaviour. Future research should therefore focus on these aspects.

So far, no research ethics have been addressed in the conceptualisation of the learning environment, as no challenges have arisen in connection with the research questions of the students. Therefore, it has not yet proven necessary to integrate the corresponding implementation principles. However, in cases where research questions with such challenges are chosen by the students, this might become important.

The applied method of participant observation might raise the question of to what extent the presence of the observer and his interaction with the students could have caused reactivity effects. Regarding the pilot cycle (and to a very limited extent possibly also regarding main cycle 1) these cannot be excluded, as during this phase interaction was necessary to find out which specific measures of guidance were needed by the students. For the main research cycles, especially cycle 2, such effects can be seen as very improbable because interaction between researchers and students was limited to small talk or organisational issues, as described above.

Further limitations relate to the applied DBR approach. So, for instance, it is obvious that the mere design of a learning environment cannot determine successful learning processes, considering the described significance of the teacher in close-to-science IBL. Possibilities in DBR to address this factor are predominantly limited to the learning environment, while, for example, teacher education can hardly be influenced. Nevertheless, through the DBR process we were able to identify design principles to support teachers in guiding students’ learning processes the best way possible, which we operationalised in the resulting learning environment and implemented into complementary measures like the aforementioned teacher training (see Section 2.1).

Besides that, the DBR approach, aiming to create a complex set of design principles as a theoretical and practical output, is not capable of identifying isolated variables. Causal statements in the format of “x leads to y” are not possible because the applied design principles always work together as a whole to achieve a particular effect. This is naturally inevitable in DBR, but at the same time this approach allows us to comprehensively capture as many potentially relevant context factors as possible and to create a learning environment that, as a whole, achieves desirable effects. This represents a great advantage in exploratory research projects.

DBR with its iterative character also brings the question about when to consider a conception and the respective design principles as “final”. In theory, the more iterations one executes, the more differentiated the output becomes. In our project, we decided to complete the research process after one pilot cycle and two main research cycles for two main reasons. First, our conception meets four central criteria that usually determine the number of iterations in practice [126,127]. It is designed on the basis of state-of-the-art knowledge (content validity), its constituting parts are linked to each other in a logical, coherent way (construct validity), the end users can apply it in the way it was intended by the developers (practicality), and it results in the desired learning outcomes (effectiveness). Second, a perpetual in-detail adaptation would not be practicable, in that beyond a certain threshold it would only result in reactions to the individual characteristics and needs of the respective learner group in which it was applied—in other words, even if the learning environment is developed to an optimal state in general, there will always be a margin for improvement when addressing a particular learner group.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.B., U.O. and J.S.; Data Curation, S.B.; Formal Analysis, S.B.; Funding Acquisition, U.O., S.B.; Investigation, S.B., J.S.; Methodology, S.B. and U.O.; Project Administration, S.B.; Supervision, U.O.; Validation, S.B., U.O. and J.S.; Visualization, S.B.; Writing—original draft, S.B.; Writing—review & editing, S.B., U.O. and J.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research project is funded by the Bavarian State Ministry for Science and Art via the bayklif research network.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Data available on request due to restrictions, e.g., privacy or ethical. The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to the privacy protection of involved teachers and students.

Acknowledgments

We want to thank Jasmin Dambacher (J.D.), Charlotte Faaß (C.F.), and Franziska Schwarz (F.S.) for their supporting work during the data analysis (transcription of focus group discussions).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Ojala, M.; Lakew, Y. Young People and Climate Change Communication. In Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Climate Science; Ojala, M., Lakew, Y., Eds.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2017; ISBN 9780190228620. [Google Scholar]

- USGCRP. Climate Literacy: The Essential Principles of Climate Science. 2009. Available online: https://downloads.globalchange.gov/Literacy/climate_literacy_highres_english.pdf (accessed on 10 March 2022).

- Azevedo, J.; Marques, M. Climate literacy: A Systematic Review and Model Integration. IJGW 2017, 12, 414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. PISA 2015 Assessment and Analytical Framework: Science, Reading, Mathematic, Financial Literacy and Collaborative Problem Solving; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2017; ISBN 978-92-64-28182-0. [Google Scholar]

- Ohl, U. Komplexität und Kontroversität: Herausforderungen des Geographieunterrichts mit hohem Bildungswert. Prax. Geogr. 2013, 43, 4–8. [Google Scholar]

- IPCC. Climate Change: The 1990 and 1992 IPCC Assessments, IPCC First Assessment Report Overview and Policymaker Summaries and 1992 IPPC Supplement; IPCC: Geneve, Switzerland, 1992; ISBN 0-662-19821-2. [Google Scholar]

- Meyer, C.; Eberth, A.; Warner, B. Einführung. In Klimawandel im Unterricht: Bewusstseinsbildung für eine Nachhaltige Entwicklung; Meyer, C., Eberth, A., Warner, B., Eds.; Diercke: Braunschweig, Germany, 2018; pp. 4–5. ISBN 9783141098204. [Google Scholar]

- Felzmann, D. Vorstellungen von Lernenden zu Ursachen und Folgen des Klimawandels und darauf aufbauende Unterrichtskonzepte. In Klimawandel im Unterricht: Bewusstseinsbildung für Eine Nachhaltige Entwicklung; Meyer, C., Eberth, A., Warner, B., Eds.; Diercke: Braunschweig, Germany, 2018; pp. 53–63. ISBN 9783141098204. [Google Scholar]

- Schuler, S. Alltagstheorien zu den Ursachen und Folgen des Globalen Klimawandels: Erhebung und Analyse von Schülervorstellungen aus Geographiedidaktischer Perspektive; Dissertation: Bochum, Germany, 2010; ISBN 978-3-89966-367-9. [Google Scholar]

- Chang, C.-H.; Pascua, L.; Ess, F. Closing the “Hole in the Sky”: The Use of Refutation-Oriented Instruction to Correct Students. Climate Change Misconceptions. J. Geogr. 2018, 117, 3–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleming, W.; Hayes, A.L.; Crosman, K.M.; Bostrom, A. Indiscriminate, Irrelevant, and Sometimes Wrong: Causal Misconceptions about Climate Change. Risk Anal. 2021, 41, 157–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Picton, I.; Teravainen, A. Fake News and Critical Literacy: An Evidence Review. 2017. Available online: https://cdn.literacytrust.org.uk/media/documents/Fake_news_and_critical_literacy_evidence_review_Sep_17.pdf (accessed on 10 March 2022).

- Lutzke, L.; Drummond, C.; Slovic, P.; Árvai, J. Priming critical thinking: Simple Interventions Limit the Influence of Fake News about Climate Change on Facebook. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2019, 58, 101964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiari, S.; Völler, S.; Mandl, S. Wie lassen sich Jugendliche für Klimathemen begeistern? Chancen und Hürden in der Klimakommunikation. GW-Unterricht 2016, 141, 5–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Renn, O. Klimaveränderungen als systemisches Risiko erkennen—Wege zur Handlungsbereitschaft. In Klimawandel Im Unterricht: Bewusstseinsbildung Für Eine Nachhaltige Entwicklung; Meyer, C., Eberth, A., Warner, B., Eds.; Diercke: Braunschweig, Germany, 2018; pp. 77–85. ISBN 9783141098204. [Google Scholar]

- Knutti, R. Closing the Knowledge-Action Gap in Climate Change. One Earth 2019, 1, 21–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- European Commission. Climate Change: Special Eurobarometer 409. 2014. Available online: http://ec.europa.eu/commfrontoffice/publicopinion/archives/ebs/ebs_409_en.pdf (accessed on 18 November 2021).

- Ranney, M.A.; Clark, D. Climate Change Conceptual Change: Scientific Information Can Transform Attitudes. Top. Cogn. Sci. 2016, 8, 49–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Gubler, M.; Brügger, A.; Eyer, M. Adolescents’ Perceptions of the Psychological Distance to Climate Change, Its Relevance for Building Concern About It, and the Potential for Education. In Climate Change and the Role of Education; Leal Filho, W., Hemstock, S.L., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 129–147. ISBN 978-3-030-32897-9. [Google Scholar]

- Fiene, C. Wahrnehmung von Risiken aus dem Globalen Klimawandel: Eine Empirische Untersuchung in der Sekundarstufe, I. Ph.D. Thesis, Pädagogische Hochschule Heidelberg, Heidelberg, Germany, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Brügger, A.; Dessai, S.; Devine-Wright, P.; Morton, T.A.; Pidgeon, N.F. Psychological responses to the proximity of climate change. Nat. Clim. Chang. 2015, 5, 1031–1037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Corner, A.; Roberts, O.; Chiari, S.; Völler, S.; Mayrhuber, E.S.; Mandl, S.; Monson, K. How do young people engage with climate change? The role of knowledge, values, message framing, and trusted communicators. WIREs Clim. Chang. 2015, 6, 523–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loy, L.S.; Spence, A. Reducing, and bridging, the psychological distance of climate change. J. Environ. Psychol. 2020, 67, 101388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gubler, M. Unterricht zum Klimawandel—eine Frage der Distanz? GeoAgenda 2019, 5, 19–23. [Google Scholar]

- Monroe, M.C.; Plate, R.R.; Oxarart, A.; Bowers, A.; Chaves, W.A. Identifying effective climate change education strategies: A Systematic Review of the Research. Environ. Educ. Res. 2017, 11, 791–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huber, L. Warum Forschendes Lernen nötig und möglich ist. In Forschendes Lernen Im Studium: Aktuelle Konzepte und Erfahrungen; Huber, L., Hellmer, J., Schneider, F., Eds.; Universitätsverlag Webler: Bielefeld, Germany, 2009; pp. 9–36. ISBN 978-3-937026-66-4. [Google Scholar]

- Messner, R. Forschendes Lernen aus pädagogischer Sicht. In Schule Forscht: Ansätze und Methoden Zum Forschenden Lernen; Messner, R., Ed.; Körber-Stiftung: Hamburg, Germany, 2009; pp. 15–30. ISBN 978-3896843357. [Google Scholar]

- Brumann, S.; Ohl, U.; Schackert, C. Researching Climate Change in Their Own Backyard—Inquiry-Based Learning as a Promising Approach for Senior Class Students. In Climate Change and the Role of Education; Leal Filho, W., Hemstock, S.L., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 71–86. ISBN 978-3-030-32897-9. [Google Scholar]

- Chu, S.K.W. 21st Century Skills Development Through Inquiry-Based Learning: From Theory to Practice; Springer: Singapore, 2017; ISBN 978-981-10-2481-8. [Google Scholar]

- Kuisma, M. Narratives of inquiry learning in middle-school geographic inquiry class. Int. Res. Geogr. Environ. Educ. 2017, 27, 85–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chen, R.H. Fostering Students’ Workplace Communicative Competence and Collaborative Mindset through an Inquiry-Based Learning Design. Educ. Sci. 2021, 11, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apedoe, X.S.; Walker, S.E.; Reeves, T.C. Integrating Inquiry-based Learning into Undergraduate Geology. J. Geosci. Educ. 2006, 54, 414–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Maktoumi, A.; Al-Ismaily, S.; Kacimov, A. Research-based learning for undergraduate students in soil and water sciences: A Case Study of Hydropedology in an Arid-Zone Environment. J. Geogr. High. Educ. 2016, 40, 321–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uzunöz, S.; Erturan Ilker, G.; Arslan, Y.; Demirhan, G. The Effect of Different Teaching Styles on Critical Thinking and Achievement Goals of Prospective Teachers. Spormetre 2018, 17, 80–95. [Google Scholar]

- Duran, M.; Dökme, I. The effect of the inquiry-based learning approach on student’s critical-thinking skills. Eurasia J. Math. Sci. Tech. Ed. 2016, 12, 2887–2908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chinn, C.A.; Duncan, R.G.; Dianovsky, M.; Rinehart, R. Promoting Conceptual Change Through Inquiry. In International Handbook of Research on Conceptual Change, 2nd ed.; Vosniadou, S., Ed.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2013; pp. 539–559. ISBN 978-0415898836. [Google Scholar]

- Kukkonen, J.E.; Kärkkäinen, S.; Dillon, P.; Keinonen, T. The Effects of Scaffolded Simulation-Based Inquiry Learning on Fifth-Graders’ Representations of the Greenhouse Effect. Int. J. Sci. Educ. 2013, 36, 406–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuan, H.-L.; Chin, C.-C.; Tsai, C.-C.; Cheng, S.-F. Investigating the Effectiveness of Inquiry Instruction on the Motivation of Different Learning Styles Students. Int. J. Sci. Math. Educ. 2005, 3, 541–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayram, Z.; Oskay, Ö.Ö.; Erdem, E.; Özgür, S.D.; Şen, Ş. Effect of Inquiry based Learning Method on Students’ Motivation. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2013, 106, 988–996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sjödahl Hammarlund, C.; Nordmark, E.; Gummesson, C. Integrating theory and practice by self-directed inquiry-based learning? A Pilot Study. Eur. J. Physiother. 2013, 15, 225–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gray, K. Assessing Gains in Science Teaching Self-Efficacy After Completing an Inquiry-Based Earth Science Course. J. Geosci. Educ. 2018, 65, 60–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ojala, M. Coping with Climate Change among Adolescents: Implications for Subjective Well-Being and Environmental Engagement. Sustainability 2013, 5, 2191–2209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Stevenson, K.; Peterson, N. Motivating Action through Fostering Climate Change Hope and Concern and Avoiding Despair among Adolescents. Sustainability 2016, 8, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Jugert, P.; Greenaway, K.H.; Barth, M.; Büchner, R.; Eisentraut, S.; Fritsche, I. Collective efficacy increases pro-environmental intentions through increasing self-efficacy. J. Environ. Psychol. 2016, 48, 12–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salomon, E.; Preston, J.L.; Tannenbaum, M.B. Climate change helplessness and the (de)moralization of individual energy behavior. J. Exp. Psychol. Appl. 2017, 23, 15–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Hamann, K.R.S.; Reese, G. My Influence on the World (of Others): Goal Efficacy Beliefs and Efficacy Affect Predict Private, Public, and Activist Pro-environmental Behavior. J. Soc. Issues 2020, 76, 35–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Markaki, V. Environmental Education through Inquiry and Technology. Sci. Educ. Int. 2014, 25, 86–92. [Google Scholar]

- Costes-Onishi, P.; Baildon, M.; Aghazadeh, S. Moving inquiry-based learning forward: A meta-synthesis on inquiry-based classroom practices for pedagogical innovation and school improvement in the humanities and arts. Asia Pac. J. Educ. 2020, 40, 552–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klein, P. Using inquiry to enhance the learning and appreciation of geography. J. Geogr. 1995, 94, 358–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, S.-L.; Chang, C.-Y.; Barufaldi, J.P. Inquiry Teaching and Its Effects on Secondary-School Students’ Learning of Earth Science Concepts. J. Geosci. Educ. 1998, 46, 363–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, C.-Y.; Mao, S.-L. Comparison of Taiwan Science Students. Outcomes with Inquiry-Group Versus Traditional Instruction. J. Educ. Res. 1999, 92, 340–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Namdar, B. Teaching global climate change to pre-service middle school teachers through inquiry activities. Res. Sci. Technol. Educ. 2018, 12, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mutlu, A. Evaluation of students’ scientific process skills through reflective worksheets in the inquiry-based learning environments. Reflective Pract. 2020, 21, 271–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arieska Putri, L.; Permanasari, A.; Winarno, N.; Jahan Ahmad, N. Enhancing Students’ Scientific Literacy using Virtual Lab Activity with Inquiry-Based Learning. J. Sci. Learn. 2021, 4, 173–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brumann, S.; Ohl, U. Forschendes Lernen im Geographieunterricht. In Vielfältige Geographien—Fachliche und Kulturelle Diversität Im Unterricht Nutzbar Machen; Obermeier, G., Ed.; Bayerischer Schulgeographentag 2018; Verlag Naturwissenschaftliche Gesellschaft Bayreuth e.V.: Bayreuth, Germany, 2019; pp. 25–41. ISBN 978-3-939146-24-7. [Google Scholar]

- Gess, C.; Deicke, W.; Wessels, I. Kompetenzentwicklung durch Forschendes Lernen. In Forschendes Lernen: Wie die Lehre in Universität und Fachhochschule Erneuert Werden Kann; Mieg, H.A., Lehmann, J., Eds.; Campus Verlag: Frankfurt, Germany; New York, NY, USA, 2017; pp. 79–90. ISBN 978-3-593-43397-4. [Google Scholar]

- Kidd, C.; Hayden, B.Y. The Psychology and Neuroscience of Curiosity. Neuron 2015, 88, 449–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Klopp, E.; Stark, R. Persönliche Epistemologien—Elemente wissenschaftlicher Kompetenz. In Denken über Wissen und Wissenschaft: Epistemologische Überzeugungen; Mayer, A.-K., Rosman, T., Eds.; Pabst Science Publishers: Lengerich, Germany, 2016; pp. 40–70. ISBN 978-3958531833. [Google Scholar]

- Wiemer, M. Forschend lernen—Selbstlernen. Selbstlernprozesse und Selbstlernfähigkeiten im Forschenden Lernen. In Forschendes Lernen: Wie die Lehre in Universität und Fachhochschule Erneuert Werden Kann; Mieg, H.A., Lehmann, J., Eds.; Campus Verlag: Frankfurt, Germany; New York, NY, USA, 2017; pp. 47–55. ISBN 978-3-593-43397-4. [Google Scholar]

- Wildt, J. Forschendes Lernen: Lernen im “Format“ der Forschung. J. Hochschuldidaktik 2009, 20, 4–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reitinger, J. Forschendes Lernen: Theorie, Evaluation und Praxis in naturwissenschaftlichen Lernarrangements; 2. Unveränderte Auflage; Prolog-Verlag: Immenhausen, Germany, 2013; ISBN 9783934575745. [Google Scholar]

- Gotzen, S.; Beyerlin, S.; Gels, A. Forschendes Lernen: Steckbrief; Zentrum für Lehrentwicklung: Köln, Germany, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Pedaste, M.; Mäeots, M.; Siiman, L.A.; de Jong, T.; van Riesen, S.A.N.; Kamp, E.T.; Manoli, C.C.; Zacharia, Z.C.; Tsourlidaki, E. Phases of inquiry-based learning: Definitions and the Inquiry Cycle. Educ. Res. Rev. 2015, 14, 47–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sonntag, M.; Rueß, J.; Ebert, C.; Friederici, K.; Deicke, W. Forschendes Lernen im Seminar. Ein Leitfaden für Lehrende; Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin: Berlin, Germany, 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huber, L. Forschendes Lernen: Bericht und Diskussion über ein hochschuldidaktisches Prinzip. Neue Samml. 1970, 10, 227–244. [Google Scholar]

- Wolf, K.D. Forschendes Lehren mit digitalen Medien: Wie forschendes lernen durch Teilhabe und mediale Unterstützung gelingen kann. In Forschendes Lernen 2.0; Kergel, D., Heidkamp, B., Eds.; Springer Fachmedien Wiesbaden: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2016; pp. 263–273. ISBN 978-3-658-11620-0. [Google Scholar]

- Zion, M.; Mendelovici, R. Moving from structured to open inquiry: Challenges and Limits. Sci. Educ. Int. 2012, 23, 383–399. [Google Scholar]

- Furtak, E.M.; Seidel, T.; Iverson, H.; Briggs, D.C. Experimental and Quasi-Experimental Studies of Inquiry-Based Science Teaching: A Meta-Analysis. Rev. Educ. Res. 2012, 82, 300–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]