Ranking Decision Making for Eco-Efficiency Using Operational, Energy, and Environmental Efficiency

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Overall Efficiency

2.2. Partial Efficiency

2.3. No Preference Information

2.4. TOPSIS

3. Illustrative Example

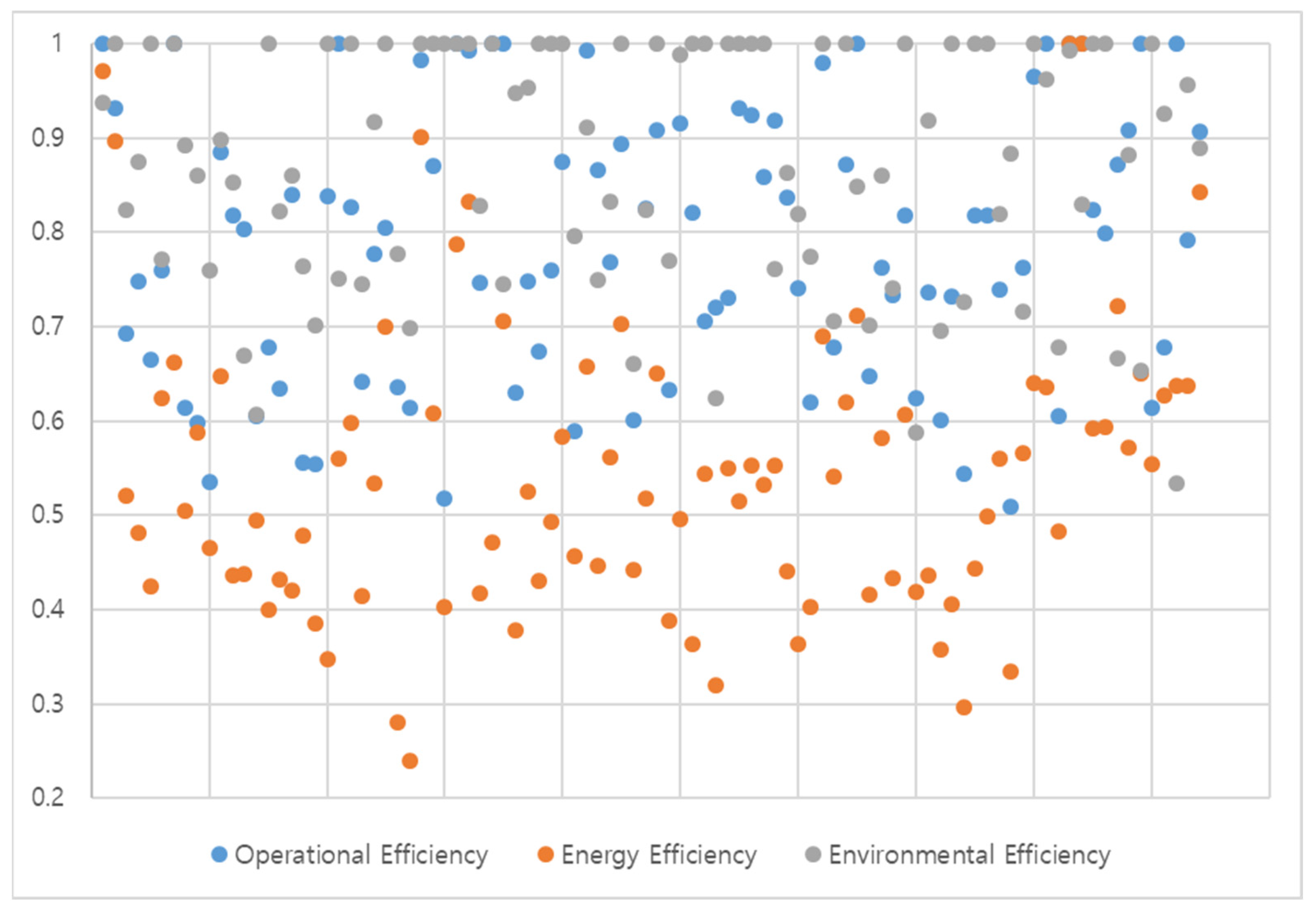

3.1. Overall Efficiency and Partial Efficiency Scores

3.2. Ranking Evaluation

4. Discussion

4.1. Theoretical Contribution

4.2. Practical Implication

5. Conclusions

- Considering the characteristics of DEA, it was shown that the derivation of the overall efficiency could not actually capture the eco-efficiency. Theoretically, this part was pointed out, and this phenomenon was confirmed and explained through an illustrative example.

- An analysis technique that can make a ranking evaluation considering the distribution of partial efficiencies, even in a situation where preference information is not requested from the decision makers, is presented.

- Another research value is that a decision-making support tool that could balance the operational, energy, and environmental aspects at the same time was presented.

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| DMU | Labor (h) | Machinery (h) | Diesel (L) | Electricity (kWh) | Herbicides (kg) | Insecticides (kg) | Urea (kg) | P2O5 (kg) | FYM (kg) | Soybean (kg) | Straw (kg) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 169 | 16 | 70 | 0 | 4 | 1.5 | 110 | 46 | 0 | 3500 | 4312 |

| 2 | 142 | 15 | 65 | 0 | 3 | 0.5 | 55 | 23 | 2500 | 3000 | 3889 |

| 3 | 197 | 22 | 88 | 1953 | 2 | 1 | 96 | 69 | 2500 | 3000 | 3889 |

| 4 | 254 | 35 | 122 | 1286 | 3 | 2 | 110 | 46 | 7500 | 3600 | 4397 |

| 5 | 138 | 32 | 111 | 1432 | 2 | 2.5 | 78 | 23 | 2222 | 3000 | 3889 |

| 6 | 152 | 28 | 98 | 0 | 3 | 2 | 110 | 46 | 2000 | 3150 | 4016 |

| 7 | 148 | 28 | 109 | 703 | 3 | 3 | 110 | 46 | 563 | 4150 | 4862 |

| 8 | 213 | 27 | 109 | 1406 | 1 | 2 | 137 | 115 | 1250 | 3500 | 4312 |

| 9 | 159 | 18 | 76 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 76 | 46 | 0 | 2300 | 3296 |

| 10 | 137 | 28 | 96 | 0 | 3 | 3.5 | 76 | 46 | 0 | 2300 | 3296 |

| 11 | 272 | 26 | 105 | 0 | 3 | 2 | 103 | 115 | 750 | 3500 | 4312 |

| 12 | 185 | 31 | 126 | 1406 | 3 | 4.5 | 82 | 92 | 1500 | 3400 | 4227 |

| 13 | 228 | 35 | 119 | 781 | 3 | 5 | 82 | 92 | 7500 | 3000 | 3889 |

| 14 | 264 | 22 | 91 | 0 | 3 | 2 | 100 | 72 | 0 | 2315 | 3309 |

| 15 | 200 | 45 | 150 | 1758 | 0 | 1.5 | 92 | 0 | 16,667 | 3750 | 4524 |

| 16 | 289 | 32 | 115 | 2179 | 3 | 1.5 | 114 | 115 | 7500 | 3250 | 4100 |

| 17 | 282 | 35 | 130 | 1758 | 3 | 2.5 | 105 | 92 | 4500 | 3500 | 4312 |

| 18 | 209 | 24 | 83 | 1524 | 3 | 1 | 92 | 0 | 6000 | 2600 | 3550 |

| 19 | 268 | 33 | 119 | 2901 | 3 | 8 | 92 | 0 | 12,500 | 3000 | 3889 |

| 20 | 210 | 55 | 168 | 1538 | 0 | 1 | 64 | 46 | 10,000 | 35,007 | 4312 |

| 21 | 139 | 27 | 108 | 732 | 3 | 4.5 | 114 | 115 | 9375 | 3500 | 4312 |

| 22 | 179 | 23 | 109 | 1154 | 5 | 0.5 | 69 | 0 | 4000 | 4000 | 4735 |

| 23 | 200 | 40 | 131 | 820 | 3 | 3.5 | 114 | 115 | 1111 | 3115 | 3986 |

| 24 | 245 | 29 | 106 | 1172 | 3 | 1.5 | 87 | 46 | 3750 | 3500 | 4312 |

| 25 | 222 | 31 | 93 | 1289 | 3 | 8 | 0 | 0 | 11,000 | 4200 | 4904 |

| 26 | 263 | 54 | 175 | 2175 | 3 | 3.5 | 92 | 0 | 12,500 | 3100 | 3974 |

| 27 | 285 | 64 | 203 | 2175 | 3 | 2.5 | 92 | 0 | 25,000 | 3000 | 3889 |

| 28 | 124 | 17 | 69 | 0 | 3 | 0.5 | 78 | 23 | 0 | 3200 | 4058 |

| 29 | 215 | 15 | 88 | 3282 | 0 | 1 | 87 | 46 | 0 | 3500 | 4312 |

| 30 | 134 | 14 | 76 | 1406 | 0 | 1.5 | 69 | 0 | 0 | 2000 | 3043 |

| 31 | 137 | 17 | 64 | 1318 | 3 | 3 | 78 | 23 | 833 | 3300 | 4143 |

| 32 | 201 | 17 | 68 | 879 | 3 | 0.5 | 110 | 46 | 0 | 3600 | 4397 |

| 33 | 159 | 38 | 128 | 2051 | 3 | 2.5 | 110 | 46 | 7500 | 3500 | 4312 |

| 34 | 269 | 50 | 160 | 732 | 3 | 5.5 | 64 | 46 | 0 | 4200 | 4904 |

| 35 | 223 | 10 | 65 | 2813 | 3 | 4.5 | 64 | 46 | 1500 | 3000 | 3889 |

| 36 | 145 | 24 | 101 | 2075 | 0 | 3 | 64 | 46 | 0 | 2500 | 3466 |

| 37 | 176 | 29 | 108 | 1172 | 3 | 2 | 64 | 46 | 2083 | 3500 | 4312 |

| 38 | 183 | 29 | 100 | 1450 | 3 | 10.6 | 48 | 35 | 208 | 2800 | 3720 |

| 39 | 167 | 23 | 93 | 3076 | 3 | 2.5 | 50 | 69 | 0 | 3000 | 3889 |

| 40 | 238 | 26 | 95 | 879 | 3 | 2.5 | 64 | 46 | 0 | 3330 | 4168 |

| 41 | 290 | 34 | 117 | 3516 | 3 | 6 | 197 | 92 | 0 | 3500 | 4312 |

| 42 | 206 | 24 | 93 | 2051 | 3 | 5 | 128 | 92 | 3000 | 4000 | 4735 |

| 43 | 350 | 21 | 120 | 1538 | 4 | 5 | 159 | 92 | 3000 | 3400 | 4227 |

| 44 | 133 | 31 | 100 | 1154 | 3 | 6.5 | 96 | 69 | 0 | 3500 | 4312 |

| 45 | 169 | 25 | 92 | 1025 | 3 | 3.5 | 0 | 0 | 6250 | 4000 | 4735 |

| 46 | 157 | 34 | 108 | 820 | 3 | 3 | 110 | 46 | 3750 | 2800 | 3720 |

| 47 | 239 | 35 | 120 | 1641 | 3 | 3.6 | 156 | 46 | 15,000 | 4000 | 4735 |

| 48 | 170 | 21 | 89 | 855 | 3 | 1.5 | 115 | 0 | 0 | 3500 | 4312 |

| 49 | 220 | 50 | 146 | 1582 | 3 | 4 | 135 | 81 | 10,000 | 3500 | 4312 |

| 50 | 277 | 29 | 117 | 2813 | 1.25 | 4.5 | 110 | 46 | 0 | 3800 | 4566 |

| 51 | 186 | 48 | 165 | 1791 | 1.5 | 3 | 92 | 0 | 21,429 | 3700 | 4481 |

| 52 | 189 | 20 | 81 | 781 | 0 | 1.5 | 64 | 46 | 0 | 2666 | 3606 |

| 53 | 104 | 35 | 124 | 2110 | 3 | 3 | 83 | 23 | 12,000 | 2600 | 3550 |

| 54 | 170 | 19 | 75 | 1465 | 3 | 2 | 92 | 0 | 0 | 2700 | 3635 |

| 55 | 112 | 20 | 101 | 2110 | 2 | 3 | 92 | 0 | 0 | 3400 | 4227 |

| 56 | 144 | 25 | 106 | 1074 | 3.5 | 0.3 | 110 | 46 | 1500 | 3570 | 4371 |

| 57 | 179 | 15 | 86 | 1978 | 0 | 1.5 | 92 | 0 | 0 | 3000 | 3889 |

| 58 | 215 | 30 | 109 | 769 | 3 | 3 | 123 | 138 | 22,500 | 3500 | 4312 |

| 59 | 146 | 34 | 134 | 1846 | 3 | 2.5 | 87 | 46 | 15,000 | 3800 | 4566 |

| 60 | 162 | 40 | 147 | 2369 | 3 | 2.5 | 87 | 46 | 15,000 | 3500 | 4312 |

| 61 | 245 | 34 | 119 | 1410 | 3 | 3 | 92 | 0 | 10,000 | 3000 | 3889 |

| 62 | 196 | 9 | 61 | 513 | 3 | 2.5 | 32 | 23 | 417 | 2500 | 3466 |

| 63 | 187 | 19 | 79 | 1934 | 2 | 2.5 | 137 | 115 | 0 | 2800 | 3720 |

| 64 | 163 | 21 | 88 | 1465 | 3 | 3 | 115 | 0 | 2500 | 3570 | 4371 |

| 65 | 243 | 21 | 86 | 824 | 3 | 3 | 123 | 138 | 5000 | 3700 | 4481 |

| 66 | 196 | 22 | 103 | 2175 | 3 | 2.5 | 137 | 115 | 0 | 2800 | 3720 |

| 67 | 178 | 26 | 100 | 0 | 3.5 | 0.3 | 110 | 46 | 1500 | 3000 | 3889 |

| 68 | 214 | 33 | 132 | 1367 | 3.5 | 3 | 110 | 46 | 7500 | 3500 | 4312 |

| 69 | 169 | 27 | 92 | 1282 | 3.5 | 0.5 | 92 | 0 | 7500 | 3600 | 4397 |

| 70 | 208 | 28 | 104 | 1432 | 3 | 3 | 123 | 138 | 20,000 | 2800 | 3720 |

| 71 | 165 | 37 | 124 | 1758 | 3 | 2 | 77 | 0 | 15,000 | 3500 | 4312 |

| 72 | 261 | 32 | 124 | 2179 | 3 | 1.5 | 114 | 115 | 7500 | 2900 | 3804 |

| 73 | 283 | 38 | 138 | 1758 | 3 | 1.5 | 69 | 0 | 5000 | 3550 | 4354 |

| 74 | 167 | 37 | 136 | 1904 | 3 | 1 | 92 | 0 | 7500 | 2600 | 3550 |

| 75 | 211 | 31 | 122 | 1477 | 0 | 1 | 46 | 0 | 10,000 | 3400 | 4227 |

| 76 | 155 | 36 | 129 | 1030 | 3 | 2.5 | 69 | 0 | 10,000 | 3800 | 4566 |

| 77 | 154 | 30 | 96 | 1007 | 3 | 2 | 110 | 46 | 7500 | 3300 | 4143 |

| 78 | 176 | 28 | 119 | 2344 | 3 | 2.5 | 92 | 0 | 0 | 2600 | 3550 |

| 79 | 195 | 18 | 89 | 1846 | 3 | 6 | 119 | 69 | 10,000 | 3300 | 4143 |

| 80 | 144 | 21 | 93 | 1641 | 2 | 3 | 137 | 115 | 0 | 3900 | 4651 |

| 81 | 108 | 29 | 98 | 820 | 3.5 | 1.5 | 64 | 46 | 7500 | 3700 | 4481 |

| 82 | 279 | 27 | 116 | 916 | 4 | 4.5 | 160 | 115 | 15,000 | 3300 | 4143 |

| 83 | 309 | 12 | 55 | 820 | 1 | 1 | 128 | 92 | 0 | 3600 | 4397 |

| 84 | 95 | 12 | 66 | 0 | 3.5 | 2.5 | 87 | 46 | 10,000 | 3400 | 4227 |

| 85 | 141 | 25 | 105 | 0 | 2 | 1.5 | 174 | 92 | 0 | 3200 | 4058 |

| 86 | 152 | 27 | 103 | 0 | 0 | 2.5 | 91 | 115 | 12,500 | 3150 | 4016 |

| 87 | 127 | 19 | 82 | 0 | 3 | 4.5 | 114 | 115 | 9375 | 3050 | 3931 |

| 88 | 121 | 21 | 84 | 1172 | 3 | 2 | 46 | 0 | 10,000 | 3100 | 3974 |

| 89 | 213 | 6 | 47 | 1074 | 2 | 1.5 | 105 | 92 | 0 | 2000 | 3043 |

| 90 | 171 | 17 | 69 | 2344 | 3 | 1 | 92 | 0 | 0 | 2500 | 3466 |

| 91 | 192 | 18 | 87 | 328 | 3 | 1 | 64 | 46 | 18,667 | 3000 | 3889 |

| 92 | 217 | 6 | 48 | 1074 | 3 | 1.5 | 105 | 92 | 0 | 2000 | 3043 |

| 93 | 199 | 19 | 72 | 2110 | 3 | 2 | 64 | 46 | 0 | 3000 | 3889 |

| 94 | 211 | 16 | 58 | 1007 | 3 | 1.5 | 110 | 46 | 0 | 3200 | 4058 |

References

- Schaltegger, S.; Sturm, A. Ökologische Rationalität-Ansatzpunkte zur Ausgestaltung von ökologieorientierten Management instrumenten. Die Unternehmung. 1990, 44, 273–290. [Google Scholar]

- Korhonen, P.J.; Luptacik, M. Eco-efficiency analysis of power plants: An extension of data envelopment analysis. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2004, 154, 437–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Picazo-Tadeo, A.J.; Beltrán-Esteve, M.; Gómez-Limón, J.A. Assessing eco-efficiency with directional distance functions. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2012, 220, 798–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hua, Z.; Bian, Y.; Liang, L. Eco-efficiency analysis of paper mills along the Huai River: An extended DEA approach. Omega 2007, 35, 578–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.M. Evaluating eco-efficiency with data envelopment analysis: An analytical reexamination. Ann. Oper. Res. 2014, 214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahlberg, B.; Luptacik, M. Eco-efficiency and eco-productivity change over time in a multisectoral economic system. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2014, 234, 885–897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kounetas, K.E.; Polemis, M.L.; Tzeremes, N.G. Measurement of eco-efficiency and convergence: Evidence from a non-parametric frontier analysis. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2021, 291, 365–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brady, K.; Henson, P.; Fava, J.A. Sustainability, eco-efficiency, life-cycle management, and business strategy. Environ. Qual. Manag. 1999, 8, 33–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeSimone, L.D.; Popoff, F. Eco-Efficiency: The Business Link to Sustainable Development; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Schaltegger, S.; Synnestvedt, T. The link between ‘green’ and economic success: Environmental management as the crucial trigger between environmental and economic performance. J. Environ. Manag. 2002, 65, 339–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reith, C.C.; Guidry, M.J. Eco-efficiency analysis of an agricultural research complex. J. Environ. Manag. 2003, 68, 219–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neto, J.Q.F.; Walther, G.; Bloemhof, J.J.; Van Nunen, A.E.E.; Spengler, T. A methodology for assessing eco-efficiency in logistics networks. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2009, 193, 670–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Avadí, Á.; Vázquez-Rowe, I.; Fréon, P. Eco-efficiency assessment of the Peruvian anchoveta steel and wooden fleets using the LCA+ DEA framework. J. Clean. Prod. 2014, 70, 118–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Chu, J.; Yin, P.; Sun, J. DEA cross-efficiency evaluation considering undesirable output and ranking priority: A case study of eco-efficiency analysis of coal-fired power plants. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 142, 877–885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caiado, R.G.G.; Heymann, M.C.; da Silveira, C.L.R.; Meza, L.A.; Quelhas, O.L.G. Measuring the Eco-efficiency of Brazilian Energy Companies using DEA and Directional Distance Function. IEEE Lat. Am. Trans. 2020, 18, 1844–1852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caiado, R.G.G.; de Freitas Dias, R.; Mattos, L.V.; Quelhas, O.L.G.; Leal Filho, W. Towards sustainable development through the perspective of eco-efficiency-A systematic literature review. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 165, 890–904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Charnes, A.; Cooper, W.W.; Rhodes, E. Measuring the efficiency of decision making units. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 1978, 2, 429–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bevilacqua, M.; Braglia, M. Environmental efficiency analysis for ENI oil refineries. J. Clean. Prod. 2002, 10, 85–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dyckhoff, H.; Allen, K. Measuring ecological efficiency with data envelopment analysis (DEA). Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2001, 132, 312–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahdiloo, M.; Saen, R.F.; Lee, K.H. Technical, environmental and eco-efficiency measurement for supplier selection: An extension and application of data envelopment analysis. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2015, 168, 279–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murty, M.; Kumar, S.; Paul, M. Environmental regulation, productive efficiency and cost of pollution abatement: A case study of the sugar industry in India. J. Environ. Manag. 2006, 79, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasurka, C.A. Decomposing electric power plant emissions within a joint production framework. Energy Econ. 2006, 28, 26–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Picazo-Tadeo, A.J.; Prior, D. Environmental externalities and efficiency measurement. J. Environ. Manag. 2009, 90, 3332–3339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, M.; Zhang, L.; An, Q.; Wang, Z.; Li, Z. Statistical analysis and combination forecasting of environmental efficiency and its influential factors since China entered the WTO: 2002–2010–2012. J. Clean. Prod. 2013, 42, 42–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sueyoshi, T.; Goto, M.; Ueno, T. Performance analysis of US coal-fired power plants by measuring three DEA efficiencies. Energy Policy 2010, 38, 1675–1688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watanabe, M.; Tanaka, K. Efficiency analysis of Chinese industry: A directional distance function approach. Energy Policy 2007, 35, 6323–6331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; An, Q.; Yao, X.; Wang, B. Environmental efficiency evaluation of industry in China based on a new fixed sum undesirable output data envelopment analysis. J. Clean. Prod. 2014, 74, 96–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Pollitt, M. Incorporating both undesirable outputs and uncontrollable variables into DEA: The performance of Chinese coal-fired power plants. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2009, 197, 1095–1105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zhang, B.; Bi, J.; Fan, Z.; Yuan, Z.; Ge, J. Eco-efficiecy analysis of industrial system in China: A data envelopment analysis approach. Ecol. Econ. 2008, 68, 306–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, P.; Ang, B.W. Linear programming models for measuring economy-wide energy efficiency performance. Energy Policy 2008, 36, 2911–2916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, P.; Ang, B.W.; Poh, K.L. Measuring environmental performance under different environmental DEA technologies. Energy Econ. 2008, 30, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahapatra, S.; Pal, R.; Hult, T.; Talluri, S. Assessment of proactive environmental initiatives: Evaluation of efficiency based on interval-scale data. IEEE Trans. Eng. Manag. 2015, 62, 280–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Calvet, R.; Conesa, D.; Gómez-Calvet, A.R.; Tortosa-Ausina, E. On the dynamics of eco-efficiency performance in the European Union. Comput. Oper. Res. 2016, 66, 336–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Wang, S.; Li, B.; Zhang, W. Dynamics, differences, influencing factors of eco-efficiency in China: A spatiotemporal perspective analysis. J. Environ. Manag. 2020, 264, 110442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Egilmez, G.; Park, Y.S. Transportation related carbon, energy and water footprint analysis of US manufacturing: An eco-efficiency assessment. Transp. Res. D Transp. Environ. 2014, 32, 143–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Lin, B. Assessment of eco-efficiency change considering energy and environment: A study of China’s non-ferrous metals industry. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 277, 123388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, J.-L.; Kao, C.-H. Efficient energy-saving targets for APEC economies. Energy Policy 2007, 35, 373–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, J.-L.; Wang, S.-C. Total-factor energy efficiency of regions in China. Energy Policy 2006, 34, 3206–3217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramanathan, R. A holistic approach to compare energy efficiencies of different transport modes. Energy Policy 2000, 28, 743–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Färe, R.; Grosskopf, S. Modeling undesirable factors in efficiency evaluation: Comment. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2004, 157, 242–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seiford, L.M.; Zhu, J. Modeling undesirable factors in efficiency evaluation. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2002, 142, 16–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Meng, W.; Li, X.; Zhang, D. DEA models with undesirable inputs and outputs. Ann. Oper. Res. 2010, 173, 177–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Färe, R.; Grosskopf, S.; Logan, J. The relative efficiency of Illinois electric utilities. Resour. Energy 1983, 5, 349–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, P.; Park, Y.J. Eco-efficiency evaluation considering environmental stringency. Sustainability 2017, 9, 661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zeydan, M.; Çolpan, C. A new decision support system for performance measurement using combined fuzzy TOPSIS/DEA approach. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2009, 47, 4327–4349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, P. Effects of the entropy weight on TOPSIS. Expert Syst. Appl. 2021, 168, 114186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shih, H.S.; Shyur, H.J.; Lee, E.S. An extension of TOPSIS for group decision making. Math. Comput. Model. 2007, 45, 801–813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cecchini, L.; Venanzi, S.; Pierri, A.; Chiorri, M. Environmental efficiency analysis and estimation of CO2 abatement costs in dairy cattle farms in Umbria (Italy): A SBM-DEA model with undesirable output. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 197, 895–907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charnes, A.; Cooper, W.W. Programming with linear fractional functionals. Nav. Res. Logist. Q. 1962, 9, 181–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roll, Y.; Cook, W.D. Partial efficiencies in data envelopment analysis. Socio-Econ. Plan. Sci. 1993, 27, 171–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golany, B. An interactive MOLP procedure for the extension of DEA to effectiveness analysis. J. Oper. Res. Soc. 1988, 39, 725–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Athanassopoulos, A.D. Decision support for target-based resource allocation of public services in multiunit and multilevel systems. Manag. Sci. 1998, 44, 173–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charnes, A.; Cooper, W.W.; Huang, Z.M.; Sun, D.B. Polyhedral cone-ratio DEA models with an illustrative application to large commercial banks. J. Econom. 1990, 46, 73–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, C.L.; Yoon, K. Multiple Attribute Decision Making, Methods and Applications; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Mohammadi, A.; Rafiee, S.; Jafari, A.; Dalgaard, T.; Knudsen, M.T.; Keyhani, A.; Mousavi-Avval, S.H.; Hermansen, J.E. Potential greenhouse gas emission reductions in soybean farming: A combined use of life cycle assessment and data envelopment analysis. J. Clean. Prod. 2013, 54, 89–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charnes, A.; Cooper, W.W.; Golany, B.; Seiford, L.; Stutz, J. Foundations of data envelopment analysis for Pareto-Koopmans efficient empirical production functions. J. Econom. 1985, 30, 91–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golany, B.; Roll, Y. An application procedure for DEA. Omega 1989, 17, 237–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talluri, S.; Huq, F.; Pinney, W.E. Application of data envelopment analysis for cell performance evaluation and process improvement in cellular manufacturing. Int. J. Prod. Res. 1997, 35, 2157–2170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, W.W.; Li, S.; Seiford, L.; Tone, L.K.; Thrall, R.M.; Zhu, J. Sensitivity and stability analysis in DEA: Some recent developments. J. Product. Anal. 2001, 15, 217–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Category | Variables |

|---|---|

| Operational Inputs | Labor, Machinery |

| Energy Inputs | Diesel, Electricity |

| Environmental Inputs | Herbicides, Insecticides, Urea, FYM, P2O5 |

| Environmental Output | Straw |

| General Output | Soybeans |

| Operational Efficiency | Energy Efficiency | Environmental Efficiency | Overall Efficiency | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | 0.787 | 0.543 | 0.872 | 0.934 |

| Median | 0.795 | 0.529 | 0.891 | 1.000 |

| S. D. | 0.144 | 0.155 | 0.129 | 0.099 |

| Range | 0.491 | 0.760 | 0.465 | 0.344 |

| Minimum | 0.509 | 0.240 | 0.535 | 0.656 |

| Maximum | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 |

| Energy Efficiency | Environmental Efficiency | Overall Efficiency | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Operational Efficiency | 0.666 (0.00) * | 0.216 (0.03) | 0.565 (0.00) |

| Energy Efficiency | 0.350 (0.00) | 0.628 (0.00) | |

| Environmental Efficiency | 0.722 (0.00) |

| DMU | Operational Efficiency | Energy Efficiency | Environmental Efficiency | Overall Efficiency | S+ | S− | C | Eco-Efficiency Rank |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1.000 | 0.971 | 0.937 | 1.000 | 0.018 | 0.200 | 0.918 | 2 |

| 2 | 0.931 | 0.896 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 0.040 | 0.178 | 0.817 | 5 |

| 3 | 0.693 | 0.521 | 0.823 | 0.836 | 0.154 | 0.067 | 0.302 | 69 |

| 4 | 0.748 | 0.481 | 0.874 | 0.888 | 0.154 | 0.075 | 0.328 | 64 |

| 5 | 0.665 | 0.425 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 0.166 | 0.090 | 0.351 | 56 |

| 6 | 0.759 | 0.624 | 0.772 | 1.000 | 0.133 | 0.082 | 0.380 | 50 |

| 7 | 1.000 | 0.662 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 0.103 | 0.145 | 0.585 | 11 |

| 8 | 0.613 | 0.505 | 0.892 | 0.970 | 0.160 | 0.071 | 0.309 | 68 |

| 9 | 0.598 | 0.587 | 0.861 | 1.000 | 0.149 | 0.076 | 0.338 | 61 |

| 10 | 0.535 | 0.465 | 0.760 | 1.000 | 0.177 | 0.045 | 0.202 | 80 |

| 11 | 0.885 | 0.647 | 0.897 | 1.000 | 0.112 | 0.112 | 0.500 | 21 |

| 12 | 0.818 | 0.436 | 0.852 | 0.895 | 0.157 | 0.078 | 0.330 | 62 |

| 13 | 0.804 | 0.437 | 0.669 | 0.903 | 0.168 | 0.059 | 0.259 | 73 |

| 14 | 0.606 | 0.494 | 0.607 | 0.783 | 0.177 | 0.038 | 0.177 | 86 |

| 15 | 0.678 | 0.400 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 0.169 | 0.089 | 0.347 | 57 |

| 16 | 0.635 | 0.432 | 0.823 | 0.823 | 0.172 | 0.055 | 0.242 | 75 |

| 17 | 0.840 | 0.420 | 0.860 | 0.872 | 0.158 | 0.081 | 0.339 | 60 |

| 18 | 0.555 | 0.479 | 0.764 | 0.923 | 0.174 | 0.047 | 0.214 | 79 |

| 19 | 0.555 | 0.385 | 0.701 | 0.704 | 0.189 | 0.030 | 0.136 | 90 |

| 20 | 0.838 | 0.347 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 0.165 | 0.102 | 0.381 | 49 |

| 21 | 1.000 | 0.560 | 0.751 | 1.000 | 0.135 | 0.111 | 0.451 | 37 |

| 22 | 0.827 | 0.598 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 0.124 | 0.114 | 0.478 | 28 |

| 23 | 0.642 | 0.414 | 0.745 | 0.745 | 0.177 | 0.043 | 0.194 | 83 |

| 24 | 0.777 | 0.534 | 0.917 | 0.983 | 0.142 | 0.089 | 0.386 | 47 |

| 25 | 0.805 | 0.700 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 0.104 | 0.126 | 0.548 | 17 |

| 26 | 0.635 | 0.281 | 0.777 | 0.797 | 0.191 | 0.042 | 0.179 | 85 |

| 27 | 0.614 | 0.240 | 0.699 | 0.780 | 0.199 | 0.028 | 0.124 | 94 |

| 28 | 0.982 | 0.900 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 0.035 | 0.185 | 0.841 | 4 |

| 29 | 0.870 | 0.608 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 0.119 | 0.120 | 0.500 | 20 |

| 30 | 0.517 | 0.402 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 0.180 | 0.086 | 0.323 | 66 |

| 31 | 1.000 | 0.788 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 0.069 | 0.163 | 0.702 | 8 |

| 32 | 0.992 | 0.832 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 0.056 | 0.171 | 0.753 | 6 |

| 33 | 0.747 | 0.418 | 0.828 | 0.841 | 0.165 | 0.064 | 0.279 | 71 |

| 34 | 1.000 | 0.470 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 0.142 | 0.130 | 0.478 | 27 |

| 35 | 1.000 | 0.705 | 0.745 | 1.000 | 0.106 | 0.129 | 0.549 | 16 |

| 36 | 0.629 | 0.378 | 0.948 | 1.000 | 0.175 | 0.075 | 0.301 | 70 |

| 37 | 0.747 | 0.526 | 0.953 | 0.964 | 0.144 | 0.091 | 0.388 | 46 |

| 38 | 0.674 | 0.430 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 0.165 | 0.090 | 0.354 | 55 |

| 39 | 0.760 | 0.493 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 0.149 | 0.099 | 0.400 | 44 |

| 40 | 0.875 | 0.583 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 0.124 | 0.118 | 0.487 | 24 |

| 41 | 0.589 | 0.457 | 0.796 | 0.834 | 0.173 | 0.051 | 0.226 | 78 |

| 42 | 0.993 | 0.657 | 0.911 | 1.000 | 0.106 | 0.132 | 0.556 | 15 |

| 43 | 0.866 | 0.446 | 0.750 | 0.881 | 0.158 | 0.076 | 0.323 | 65 |

| 44 | 0.768 | 0.562 | 0.832 | 1.000 | 0.140 | 0.079 | 0.361 | 53 |

| 45 | 0.894 | 0.702 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 0.096 | 0.135 | 0.583 | 12 |

| 46 | 0.600 | 0.442 | 0.661 | 0.666 | 0.181 | 0.033 | 0.156 | 89 |

| 47 | 0.825 | 0.518 | 0.824 | 0.901 | 0.145 | 0.081 | 0.359 | 54 |

| 48 | 0.907 | 0.650 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 0.108 | 0.129 | 0.545 | 18 |

| 49 | 0.634 | 0.389 | 0.770 | 0.770 | 0.180 | 0.044 | 0.196 | 82 |

| 50 | 0.915 | 0.496 | 0.988 | 1.000 | 0.139 | 0.115 | 0.452 | 35 |

| 51 | 0.821 | 0.364 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 0.164 | 0.100 | 0.379 | 51 |

| 52 | 0.706 | 0.544 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 0.144 | 0.099 | 0.408 | 41 |

| 53 | 0.721 | 0.320 | 0.623 | 0.830 | 0.189 | 0.037 | 0.162 | 88 |

| 54 | 0.731 | 0.550 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 0.141 | 0.101 | 0.418 | 39 |

| 55 | 0.932 | 0.514 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 0.135 | 0.121 | 0.471 | 31 |

| 56 | 0.924 | 0.552 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 0.128 | 0.122 | 0.487 | 23 |

| 57 | 0.858 | 0.533 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 0.135 | 0.112 | 0.452 | 34 |

| 58 | 0.918 | 0.553 | 0.761 | 0.920 | 0.138 | 0.094 | 0.406 | 42 |

| 59 | 0.837 | 0.440 | 0.862 | 0.932 | 0.155 | 0.082 | 0.346 | 58 |

| 60 | 0.741 | 0.364 | 0.819 | 0.837 | 0.173 | 0.060 | 0.258 | 74 |

| 61 | 0.619 | 0.403 | 0.775 | 0.780 | 0.179 | 0.044 | 0.199 | 81 |

| 62 | 0.980 | 0.690 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 0.096 | 0.145 | 0.602 | 9 |

| 63 | 0.678 | 0.541 | 0.705 | 0.781 | 0.158 | 0.056 | 0.261 | 72 |

| 64 | 0.871 | 0.620 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 0.117 | 0.121 | 0.509 | 19 |

| 65 | 1.000 | 0.711 | 0.848 | 1.000 | 0.096 | 0.136 | 0.586 | 10 |

| 66 | 0.647 | 0.415 | 0.701 | 0.750 | 0.179 | 0.038 | 0.175 | 87 |

| 67 | 0.762 | 0.582 | 0.859 | 1.000 | 0.136 | 0.085 | 0.384 | 48 |

| 68 | 0.733 | 0.433 | 0.740 | 0.766 | 0.168 | 0.053 | 0.239 | 76 |

| 69 | 0.818 | 0.606 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 0.123 | 0.114 | 0.480 | 26 |

| 70 | 0.625 | 0.418 | 0.587 | 0.656 | 0.187 | 0.028 | 0.131 | 92 |

| 71 | 0.736 | 0.436 | 0.919 | 0.958 | 0.160 | 0.079 | 0.329 | 63 |

| 72 | 0.601 | 0.357 | 0.695 | 0.695 | 0.189 | 0.029 | 0.135 | 91 |

| 73 | 0.731 | 0.406 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 0.164 | 0.093 | 0.362 | 52 |

| 74 | 0.544 | 0.296 | 0.726 | 0.798 | 0.198 | 0.029 | 0.128 | 93 |

| 75 | 0.818 | 0.444 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 0.153 | 0.102 | 0.400 | 43 |

| 76 | 0.818 | 0.499 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 0.144 | 0.105 | 0.422 | 38 |

| 77 | 0.739 | 0.561 | 0.820 | 0.855 | 0.144 | 0.075 | 0.343 | 59 |

| 78 | 0.509 | 0.334 | 0.883 | 0.883 | 0.190 | 0.059 | 0.236 | 77 |

| 79 | 0.762 | 0.566 | 0.716 | 0.853 | 0.147 | 0.069 | 0.319 | 67 |

| 80 | 0.965 | 0.641 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 0.108 | 0.137 | 0.558 | 13 |

| 81 | 1.000 | 0.636 | 0.962 | 1.000 | 0.109 | 0.137 | 0.556 | 14 |

| 82 | 0.606 | 0.483 | 0.678 | 0.715 | 0.174 | 0.040 | 0.188 | 84 |

| 83 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 0.992 | 1.000 | 0.002 | 0.213 | 0.991 | 1 |

| 84 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 0.829 | 1.000 | 0.037 | 0.202 | 0.847 | 3 |

| 85 | 0.824 | 0.592 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 0.126 | 0.113 | 0.473 | 30 |

| 86 | 0.799 | 0.594 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 0.127 | 0.111 | 0.465 | 32 |

| 87 | 0.871 | 0.722 | 0.666 | 1.000 | 0.113 | 0.108 | 0.488 | 22 |

| 88 | 0.909 | 0.572 | 0.882 | 1.000 | 0.128 | 0.105 | 0.452 | 36 |

| 89 | 1.000 | 0.650 | 0.653 | 1.000 | 0.125 | 0.118 | 0.485 | 25 |

| 90 | 0.613 | 0.554 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 0.150 | 0.096 | 0.391 | 45 |

| 91 | 0.678 | 0.627 | 0.926 | 1.000 | 0.132 | 0.094 | 0.416 | 40 |

| 92 | 1.000 | 0.637 | 0.535 | 1.000 | 0.137 | 0.115 | 0.455 | 33 |

| 93 | 0.791 | 0.637 | 0.957 | 1.000 | 0.119 | 0.108 | 0.475 | 29 |

| 94 | 0.906 | 0.843 | 0.889 | 1.000 | 0.063 | 0.152 | 0.707 | 7 |

| Overall Efficiency Rank | Eco-Efficiency Rank | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Spearman | Kendall | Spearman | Kendall | |

| Operational Efficiency Rank | 0.590 | 0.472 | 0.858 | 0.658 |

| Energy Efficiency Rank | 0.618 | 0.485 | 0.683 | 0.686 |

| Environmental Efficiency Rank | 0.712 | 0.616 | 0.618 | 0.473 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lee, P. Ranking Decision Making for Eco-Efficiency Using Operational, Energy, and Environmental Efficiency. Sustainability 2022, 14, 3489. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14063489

Lee P. Ranking Decision Making for Eco-Efficiency Using Operational, Energy, and Environmental Efficiency. Sustainability. 2022; 14(6):3489. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14063489

Chicago/Turabian StyleLee, Pyoungsoo. 2022. "Ranking Decision Making for Eco-Efficiency Using Operational, Energy, and Environmental Efficiency" Sustainability 14, no. 6: 3489. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14063489

APA StyleLee, P. (2022). Ranking Decision Making for Eco-Efficiency Using Operational, Energy, and Environmental Efficiency. Sustainability, 14(6), 3489. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14063489